2

Black Soldiers Go West

I propose now simply to carry them into the Army, to protect them in all their civil rights, to make them believe they are men in the eyes of the law and in the eye of their Maker, to enable them to ameliorate their own condition, and to reach the highest possible point of elevation their nature is capable and susceptible of. When we have done that and they have done that, both of us will have discharged our duty.

—Senator James H. Lane of Kansas, January 1866

SERGEANT MAJOR CHRISTIAN A. FLEETWOOD MUSTERED OUT OF THE U.S. army for good in May 1866, but his personal pride in having served in the USCT endured, as did his dedication to Frederick Douglass’s 1863 promise about the potential implications of black men’s military service for uplifting the race. Just over a year after he returned to civilian life, Fleetwood took note of the creation in North Carolina—where his regiment had been stationed at the end of the war—of a state branch of the “Colored Soldiers’ and Sailors’ League.” The state organization’s president described the league’s members as being pledged “to combine and connect ourselves together, that we may at this present, as well as in the future, preserve our great blessing, the ballot-box, as we did the United States muskets which the Government placed in our hands” during the recent war. “I feel constrained to use every effort in my power to aid my comrades in arms to preserve those rights which we have fought for, which we have bled for, and for which many have died.”1

Such words vividly expressed Fleetwood’s own feelings as he settled in Washington, D.C., married Sarah Iredell, fathered two children (only one of whom, Edith, reached adulthood), set about building a reasonably successful professional career based on his abundant clerical and bookkeeping skills—taking a job as an “extra clerk” at the U.S. Supreme Court, becoming an employment agent for the Freedmen’s Bureau, and later working for what was called the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company—and resuming the same sorts of social activities that had enriched his antebellum life. Through it all, Fleetwood’s experience with the USCT, and the sacrifices he and almost 200,000 other black men had made on the nation’s behalf, remained fundamental to his self-understanding, even as they contributed to his growing reputation and prominence among black Washingtonians.2

Meanwhile, the victorious federal government continued the demobilization of the army’s white volunteers and, much more slowly, its black ones. At the same time, the government and its military arm engaged in a series of wide-ranging and often contentious debates concerning the size and shape the postwar Regular army should assume. As these debates got underway, the long-term future of black Americans’ participation in the federal armed forces remained unclear, despite their disproportionately high representation in the occupation forces stationed across the former Confederacy. Over time, however, matters of practicality competed with other concerns, including such basic issues as how to harness sufficient manpower to complete the military’s numerous postwar tasks. These considerations unavoidably led the politicians and military men involved in the debates to consider the possibility of carving out a permanent role for black men within the Regular army, although opinions varied on precisely what that role might be. If the postwar army opened its doors to black men, should black men be enlisted as soldiers or only as laborers? Should they be allowed to serve as commissioned officers, or should they be held to noncommissioned status, as even the most talented, like Fleetwood, had been? Should black men, if enlisted, be confined to segregated units, or should they be integrated into biracial regiments?

With over 100,000 black soldiers still on occupation duty in the former Confederacy, as early as June 1865 one “H.C.M.” wrote from Savannah, Georgia, to the editor of the Army and Navy Journal to convey his thoughts. Expressing admiration for the USCT’s veterans, H.C.M., who was probably a white officer, urged that as many as 75,000 black men now be granted access to the postwar military, whose size, he predicted, would surely be about 125,000 (it actually turned out to be less than half that, at 54,000). Black soldiers’ “endurance and valor” had already been proved; indeed, “unprejudiced minds” could no longer question their “equality with the average of white troops” on numerous fronts, especially in cases, he noted—echoing a familiar refrain—where black soldiers operated under the authority of high-quality white officers. H.C.M., it seems, envisioned the creation of a postwar equivalent of the USCT: a “Corps d’Afrique,” as he called it, whose foundation would ideally be composed of “picked” USCT veterans.3

The very next month, “N” dispatched a letter of protest to the Journal, arguing that, “till it can be shown that they have rendered better service than our white troops,” the postwar army’s doors should be closed to blacks. He continued, “[T]here are serious objections to keeping up a large army of men whose mental faculties are undeveloped…. As we must have a large Army for some time to come, let us have one composed of men who can read and think for themselves—men who know right from wrong…and who have too much independence of character to be too ‘obedient.’” Moreover, given that it was only proper for at least “a certain proportion” of the promotions in the army to be “made from the ranks,” N went on to point out that the enlistment of black soldiers in the postwar army might eventually mean that white officers would be forced to associate directly with them. Worse still, white soldiers (including officers) might find themselves commanded by black officers of higher rank. In the end, he concluded, was it not really best to deploy all black men—who appeared, after all, to be “naturally” suited to the climate anyway—into Southern agriculture instead of military service?4

Conflicting proposals such as these developed in the shadow of congressional and high-level military debates on the same questions. One very important U.S. army officer who chimed in was Ulysses Grant, who seems to have been decidedly ambivalent. Grant did not deny that the soldiers of the USCT had served competently and even heroically during the war, but in keeping with his variable opinions regarding the use of black soldiers as occupation troops in the former Confederacy, he had some concerns about opening the Regular army to long-term black enlistment. Writing to the chair of the Senate’s Committee on Military Affairs in early 1866, Grant explained that, while he favored authorizing President Johnson “to raise twenty thousand colored troops if he deemed it necessary,” he did not recommend creating permanent regiments of “colored” soldiers. As he put it, “our standing army in time of peace should have the smallest possible numbers and the highest possible efficiency.” Grant may well have considered white soldiers fundamentally more “efficient” than black ones. More likely, he feared that allowing blacks to enlist on a continuing basis in the Regular army would limit the army’s overall effectiveness, especially if the racial tensions evident in the Reconstruction South arose in other places requiring the military’s presence. In the event that black troops did become a permanent component of the Regular army—to which Grant admittedly did not express a strong objection—he supported their segregation into separate units.5

If Grant was ambivalent about the prospect of creating permanent black Regular army regiments, Senator James A. McDougall of California was not. “I wish to express my thought,” he declared during the same congressional hearings Grant had addressed, “that the people of my country,” by which he clearly meant white people, “are able to maintain themselves, and do not need to be maintained by an inferior race.” For clarification, McDougall added his considered opinion that, “to place a lower, inferior, different race upon a level with the white man’s race, in arms, is against the laws that lie at the foundation of true republicanism.” One of McDougall’s fellow Democrats, Senator Willard Saulsbury Sr. of Delaware, concurred, drawing on the evidence of growing tensions between white former Confederates and USCT occupation troops to make his point. “If the object of Congress is, and certainly it should be, to restore kind feelings and friendly relations between the different sections of the country,” he argued—again, clearly referring only to the white people of the “different sections”—“they should do nothing which in itself is calculated to aggravate feelings already excited or to arouse feelings which may now be dormant. What would be the effect if you were to send negro regiments into the community in which I live”—namely, border-state Delaware, which had about eighteen hundred slaves at the beginning of the Civil War—“to brandish their swords and exhibit their pistols and their guns? Their very presence would be a stench in the nostrils of the people from whom I come.”6

Still, as had been the case during the Civil War, a number of leading politicians unequivocally supported the idea of establishing black regiments. Among them was the Republican senator Benjamin Wade of Ohio, one of the “radicals” in the party who, like many other supporters, defended the idea of permanent regiments of black soldiers on the basis of the USCT’s performance and reliability during the war and since. “I am informed,” Wade declared, “that while we lose greatly by desertion all the time from the white regiments…there is scarcely anything of the kind among the colored troops.” Responding specifically to Saulsbury’s point about the need to avoid further aggravating white Southerners, many of whom were becoming ever more violently bitter about emancipation and blacks’ service as occupation forces, Wade added, “If it is necessary to station troops anywhere to keep the peace in this nation, I do not care how obnoxious they are to those who undertake to stir up sedition…. I care but little whether the insurrectionists like the kind of troops that we station there to keep them in order or not.”7

Also supportive of black enlistment in the postwar army was the Republican senator James Henry Lane of Kansas, who, as a brigadier general during the war, had—like David Hunter and John W. Phelps—begun recruiting and organizing black troops for federal army service as early as 1862, even before Lincoln and his government were prepared to do so. Now Lane pointed out that, upon being presented with the proposed Army Reorganization Bill, Secretary of War Stanton, Generals Meade and Sherman, as well as Generals Thomas and Grant had essentially given their approval. “Colored troops,” Lane argued, “are sufficient for these grand leaders who have led your armies to victory and suppressed the rebellion.” On what basis, then, could they possibly be excluded from postwar military service? And while Lane made it clear that he did not believe that blacks and whites were equal in every way, he conceded, “After three hundred years of oppression the white race would be very different from what they are now.” Like so many others in his time, Lane also erroneously believed that blacks could tolerate the climate in the South, and the diseases endemic to it, “a great deal better than the white troops.” But this was hardly his main reason for supporting black enlistment.8

By midsummer of 1866, the question of black men’s immediate future in the U.S. army was decided when Congress passed its “Act to increase and fix the Military Peace Establishment of the United States” (the Army Reorganization Act). Although we do not have access to Christian Fleetwood’s response to this momentous development, it is safe to assume that he would have been pleased. For this bill, signed into law by Andrew Johnson on July 28—just two days before the bloody riot erupted in New Orleans—“opened a new chapter in American military history.” Of the sixty regiments (forty-five infantry, ten cavalry, and five artillery) the act mandated for the 54,000-man army—which was more than three times the size of its antebellum predecessor—six (the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry and the Thirty-eighth through the Forty-first Infantry regiments) were to be reserved for black soldiers. Cavalry and artillery regiments, black as well as white, were to be made up of twelve companies each (called “troops” in the cavalry and “batteries” in the artillery), while each infantry regiment would consist of ten companies. For all three branches of the service, a company (or troop, or battery) could enlist up to sixty-four men, who were eligible for promotion to the noncommissioned ranks of corporal and sergeant. Each of these groups of soldiers came under the command of a commissioned captain, first lieutenant, and second lieutenant. Each regiment, in turn, came under the command of a colonel, a lieutenant colonel, and from one to three majors. Beginning in March 1869, subsequent reorganizations of the army reduced the total number of infantry regiments to twenty-five and consolidated the four black infantries into two, redesignating them the Twenty-fourth and the Twenty-fifth. But these changes did not affect the internal organization or size of the regiments themselves. Black soldiers remained around 10 percent of the U.S. army until the end of the nineteenth century, and totaled about 25,000 during this period.9

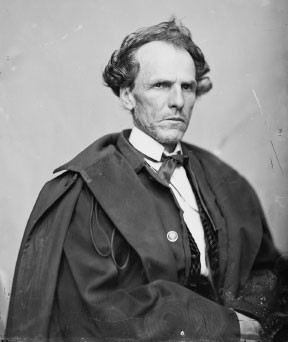

Senator James H. Lane of Kansas, ca. 1866. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Significantly, although the July 1866 act did not so stipulate, it was widely understood that the six new black regiments would have white men as their commissioned and commanding officers, a pattern established previously with the USCT that even the most enthusiastic white supporters of black enlistment seemed unwilling to alter. To be fair, in the summer of 1866 there were few potential recruits with the qualifications of someone like Fleetwood, in other words, the education, training, and experience of command considered necessary for any army post above sergeant. Because the teaching of reading and writing to slaves had long been a crime in the South, the vast majority of the men who first enlisted in the new black regiments were severely undereducated and, in many cases, illiterate, which meant that in the early years of the black Regular regiments, white commissioned officers found themselves doing much of the administrative work usually delegated to subordinates. “I beg to call especial attention to the great labor thrown upon the officers of the colored regiments,” wrote Lieutenant Colonel James H. Carleton early on, after an inspection of the black Twenty-fifth Infantry, “in being obliged to make all rolls, returns, accounts, and keep all books with their own hands. There should be employed under authority of law, an educated clerk, white or black…whose duty should be to do all of the official writing in the books, and on the rolls of the company, and be obliged to teach the men to read and write.” Anticipating this problem, the July 1866 act assigned to each black regiment a white chaplain explicitly for the purpose of running a school for the enlisted men. Still, as Carleton’s observations make clear, the results of these efforts were hardly immediate; the upshot was that most white officials early on were disinclined to challenge previous discriminatory practices, and black soldiers’ exclusion from the commissioned officers’ ranks continued.10

As General Grant and Secretary of War Stanton sorted through the likely candidates to command the new black regiments, with the help and advice of Generals Sherman and Sheridan, they therefore considered only white men, specifically veteran officers of the federal army who had sparkling Civil War records. They made their selections with care, and in the end, all of their choices were good ones, though some were more enduring than others and a few missteps occurred along the way. Among the veteran officers who initially came under consideration for command of a black Regular regiment was George Armstrong Custer, whose stunning performance during the war—he was only twenty-one when the Civil War broke out—had led to his promotion to the rank of major general of U.S. volunteers by the spring of 1865. Still, like so many accomplished veteran officers, Custer found his place in the postwar Regular army uncertain because of demobilization and downsizing. One thing is clear, however: Custer believed himself much too good for an assignment with a black regiment, and thus he vigorously turned down the lieutenant colonelcy of the black Ninth Cavalry, inadvertently setting up his subsequent appointment to command of the all-white Seventh. As it turned out, this crudely racist decision by the “dashing ‘boy general’” ultimately redounded to the Ninth’s benefit, not least because of the catastrophe that awaited Custer and the Seventh Cavalry in their confrontation with the Sioux at Montana’s Little Bighorn River in 1876.11

Of all the new black regiments, it was the Tenth Cavalry that ended up benefiting from the greatest stability at the top. Benjamin Henry Grierson became the Tenth’s colonel and went on to spend the bulk of his postwar career in the regiment’s command. Not unlike Colonel Samuel A. Duncan, who had offered such warm praise to Christian Fleetwood at the time of his mustering out from the Fourth U.S. Colored Infantry, Grierson firmly believed that a black man could be “intelligent, honest & faithful,” could provide military service to the nation that was “full of honor,” could “conduct himself with gallantry,” and deserved rich opportunity, acknowledgment, and reward for doing so. From 1866 to 1888, Grierson contributed with unusual vigor and dedication to making his case on black soldiers’ behalf.12

That Grierson would end up giving so many years of his life to the U.S. army, however, was hardly self-evident in his youth. Born on July 8, 1826, in what was then the frontier town of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Grierson was the sixth and youngest child of Irish immigrants. When Benjamin was a little over two, his family moved to Youngstown, Ohio, where the future cavalry commander at the age of eight narrowly escaped death when a skittish horse kicked him in the head. The injury left Grierson with a long scar on the side of his face and, he claimed, a lingering fear of—or perhaps it was respect for—horses.13

As a youth Grierson was described as having a mild, uncombative temperament and a love of music; over time he became proficient with a number of different instruments, including the drum, piano, violin, guitar, and clarinet, and played in the Youngstown band. After graduating from the Youngstown Academy, Grierson took a job as a clerk in a local store, but he continued to pursue music on the side, teaching and repairing instruments and also organizing a minstrel band. It was music that first drew him, ironically, into the military, as a bugler for a regiment of cavalry in the Ohio state militia.14

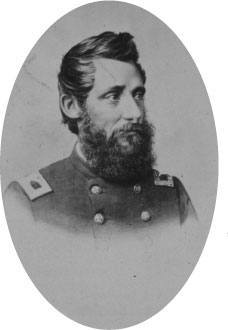

Major General Benjamin H. Grierson, ca. 1865. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

In 1849, when Grierson was twenty-three years old, his family’s quest for economic opportunity led them to Jacksonville, Illinois, not far from Springfield. There Grierson lived with his parents, making a modest living as a musician and bandleader. Five years later, he finally struck out on his own, marrying the schoolteacher Alice Kirk. The Grier sons’ first child, a son they named Charles Henry, arrived less than a year after their wedding; not long afterward, they moved about twenty miles away (but still in Illinois) to Meredosia, where Grierson tried his hand at mercantile pursuits and became active in the Illinois Republican Party. Grierson’s commitment to the party’s antislavery principles riled some in his overwhelmingly Democratic community, but enhanced his stature among local Republicans as well as party luminaries. In 1858, Abraham Lincoln himself spent a night at the Grierson home.15

When the Civil War broke out, Grierson got to work right away helping to organize a company of soldiers for the Tenth Illinois Infantry. In May he accepted an unpaid post as aide-de-camp to Benjamin Prentiss, the commander of the Illinois state troops stationed at Cairo, and at the end of October, Grierson received his first commission, as a major in the Sixth Illinois Cavalry. Worried that his lack of a West Point education might put him at a disadvantage—after all, since 1802 the U.S. Military Academy had been the nation’s primary academic venue for training its army’s commissioned officers—Grierson immersed himself in books on military tactics. Then, in late November, he joined the regiment in Shawneetown, Illinois, where he found the camp conditions dreadful, matériel and horses in extremely short supply, the troopers themselves virtually untaught, and the commanding officer, Colonel T. M. Cavanaugh, absent.16

Faced with these circumstances, Grierson took it upon himself to transform at least his own recruits into first-class cavalrymen and their bivouac into a manageable environment. By the end of the year, his troopers were displaying discipline, organization, and military skill, as well as improved morale, thanks to the upgrades he was able to engineer in their living situation. Impressed with Grierson’s ongoing dedication to the well-being and preparedness of the men and the cleanliness and order of their camp (especially in the face of Colonel Cavanaugh’s lack of interest), in early April 1862 almost forty of the regiment’s other officers signed a petition to the Illinois governor demanding Cavanaugh’s replacement by Grierson as the Sixth’s colonel. In a matter of days, the governor effected the change. Within a few weeks of assuming command, Grierson made sure that the regiment was fully supplied with weapons. Although Grierson’s supposedly “mild” personality hardly seemed to predispose him to face so unblinkingly the challenges of military leadership, his success in confronting one obstacle after another, effectively and without hesitation, boded well for his future with the black Tenth Cavalry after the war.17

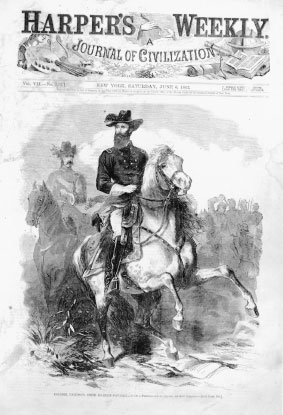

In mid-June 1863, Grierson took five companies of his own regiment and four of the Eleventh Illinois Cavalry into action in a successful raid on a Confederate guerrilla encampment in Mississippi. It was the first of a series of raids for which he would become famous, and whose effectiveness impressed General Sherman so much that he rewarded Grierson with a silver-plated carbine and declared the former music teacher with a lingering distrust of horses to be his finest cavalry commander. Grant, too, developed great confidence in Grierson’s skill, and in mid-April 1863, after several failed attempts to capture the Confederate stronghold at Vicksburg, he selected Grierson to divert Confederate attention away from Grant’s own operations. On April 17, Grierson and his 1,700-man brigade moved out from La Grange, Tennessee, and over the course of the next sixteen days, with minimal losses, traveled six hundred miles while fighting small battles, killing and wounding enemy soldiers, capturing others, seizing animal stock, and destroying rail and telegraph lines, enemy weapons, and other supplies. When Grier son and his exhausted raiders, who had done much more than just create a diversion, resurfaced at Baton Rouge, Louisiana, on May 2, both Grant and Sherman were wonderfully impressed. In the wake of the raid, Grier son enjoyed promotion to brigadier general, along with newfound fame as a national hero whose picture appeared on the cover of Harper’s Weekly and other popular publications.18

Toward the very end of 1864, Grierson led another major raid—a 450-mile, sixteen-day ride into Mississippi involving 3,500 white troopers, 50 black laborers, and a bare minimum of supplies. Like that in 1863, the raid in 1864–65 was a triumph, in the course of which the raiders attracted a following of about 1,000 slaves, eagerly claiming their freedom. The raid, during which Grierson’s men managed to burn, in just one evening, more than thirty railroad cars and two hundred wagons full of supplies destined for the Confederate forces, led to Grierson’s brevet promotion to major general of volunteers, as well as personal interviews with Lincoln, Grant, and Stanton in Washington. At the end of the summer of 1865, he took command of the District of Northern Alabama, where he found himself in overall authority over several regiments of black occupation troops, although he seems to have had little direct contact with the men.19

Harper’s Weekly cover, celebrating Grierson’s 1863 raid. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Grierson’s Reconstruction duty in Alabama lasted less than half as long as Christian Fleetwood’s in North Carolina; Grierson’s mustering-out orders arrived in mid-January 1866. Like Fleetwood’s, however, Grierson’s Civil War service had confirmed his love of the military—particularly its cavalry arm—and his aptitude for command. It had also provided him with direct experience of the horrors of slavery, while enabling him to act in a most satisfying way upon his Republican, abolitionist sentiments. At the same time, as war gave way to Reconstruction, Grierson not only briefly worked (admittedly at a distance) with black troops but also witnessed firsthand the many ways in which white Southerners aimed to undermine the war’s promise for black Americans. For these reasons and more, it was to the benefit of many of the black men who sought to follow the footsteps of United States Colored Troops into the black regiments of the postwar Regular army that Grier son’s period of separation from the military was brief, and his tenure with the Tenth Cavalry long.

The postwar Ninth Cavalry also enjoyed considerable stability, thanks to the appointment of the able veteran officer Edward Hatch, a native of Bangor, Maine. Hatch had been the Second Iowa Cavalry’s colonel during the war, before being promoted in 1864 to brigadier general and put in command of a cavalry division, with which he served to great acclaim later that year at the Battles of Franklin and Nashville, where he witnessed the USCT troops’ admirable performance. Hatch was pleased after the war to accept the colonelcy of the Ninth and remained in command of the regiment until his untimely death in April 1889, at the age of fifty-eight. After his death, Hatch was replaced by Colonel Joseph G. Tilford, a West Point graduate and Civil War veteran who, by the time he replaced Hatch, had spent twenty years with the Seventh Cavalry.20

To command the new black Thirty-eighth Infantry, Grant and Stanton turned to William Babcock Hazen of Vermont, an 1855 graduate of West Point who had served during the Civil War in every major action in the western theater, from Perryville through Sherman’s march through the Carolinas, and who by war’s end had been brevetted to the level of major general. For the Thirty-ninth they chose Joseph Anthony Mower, also of Vermont, who had accumulated a Civil War record as impressive as Hazen’s, commanding first a regiment (the Eleventh Missouri), then a brigade, a division, and a corps, and earning Sherman’s enthusiastic endorsement as “the boldest young soldier we have” in 1863, when he was only thirty-six years old. For the Forty-first they selected Ranald S. Mackenzie of New York, valedictorian of West Point’s class of 1862, who served in both the eastern and the western theaters and was, while colonel of the Second Connecticut Heavy Artillery, instrumental in challenging Confederate General Jubal A. Early’s raid on the federal capital in July 1864. Later, Mackenzie served under Sheridan in command of a cavalry brigade in the Shenandoah Valley, and subsequently a cavalry division in the siege of Petersburg, in which Christian Fleetwood and the USCT had performed so well. Mackenzie was also active in the Appomattox campaign.21

One veteran officer who seemed particularly pleased to be chosen for a colonelcy in any postwar Regular army regiment, black or white, was Nelson Miles, who since May 1865 had been serving unhappily as Jefferson Davis’s jailer at Fortress Monroe. Appointed to lead the new black Fortieth Infantry, Miles came to the post, like Grierson and the others, on the heels of a highly celebrated Civil War career, which culminated in his command of an infantry division during the Appomattox campaign. When he wrote to Miles in August 1866, Secretary of War Stanton made clear his esteem and his determination to keep Miles in the army: “I shall spare no effort to obtain for you one of the new regiments as a just acknowledgment of your distinguished service and gallantry.”22

Grierson, Hatch, Hazen, Mower, Mackenzie, and Miles: these six experienced and highly respected veteran officers of the U.S. army became the founding commanders of the postwar army’s black regiments. As it turns out, however, in contrast to their counterparts in the cavalry units, not one of the four infantry commanders remained at his post for very long. To some extent this was a function of the March 1869 consolidation of the four infantry regiments into two, in conjunction with Congress’s attempt to further diminish the size and cost of the Regular army. “We cannot play the part of empire-founders, of continent-absorbers,” grumbled the Army and Navy Journal, in response to this downsizing, “without being prepared to keep up an Army more than 25,000 to 30,000 strong. The sentiment of our people, tired of war though it may be, yet sets strongly toward the acquisition of territory. The timidest thinkers admit that it is but a question of time when Canada and Mexico and the ‘Isles of the Sea’ shall gravitate to the American Union.” Still, Congress pressed forward, with the result that the Thirty-eighth and the Forty-first Infantry regiments became the Twenty-fourth under Colonel Mackenzie, while Hazen transferred to the white Sixth Infantry. When the black Thirty-ninth and Fortieth became the Twenty-fifth Infantry under Colonel Mower’s command, Miles took charge of the white Fifth Infantry.23

Because structural changes in the army itself propelled Hazen and Miles into other assignments, it would be unfair to jump to the conclusion that they had found the command of black troops distasteful. Indeed, Miles, for one, had a long history of antislavery sentiment, and he seems to have taken an earnest and dedicated approach to his leadership of the Fortieth Infantry, which earned him, in 1869, an official recommendation from North Carolina’s Reconstruction governor, William W. Holden, that he be promoted to brigadier general. Among other things, Miles displayed a strong commitment to training and maintaining discipline among his soldiers. He also expressed concern, on more than one occasion, that the black soldiers under his authority (and enlisted men generally) be treated fairly by the federal government. “At present,” he wrote to Representative James A. Garfield in 1868,

the rank and file are, in my opinion, greatly neglected in point of pay, food and instruction…. They are made to perform all kinds of drudgery; subsist on the coarsest of food, and, as a general thing, their quarters are anything but comfortable…. Would it not be better to have more intellectual training and less of this dull role of duty, which after a certain time, neither improves the soldier physically or mentally[?]…If the soldiers were well cared for, and there was a prospect that true merit and talent would be rewarded by promotion, and the position of a United States Soldier made a more creditable one, our Army would be filled with some of the best young men in the country.24

Miles cared deeply about the welfare of his soldiers; he also demonstrated a clear awareness of the socially and politically transformative implications of black men’s military service in the South, and was eager to protect their voting rights. In late 1867, three years before the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment legally guaranteeing black male suffrage, Miles insisted that “no apprehension need arise that the colored man will not use his gift with discretion.” Indeed, in the fall of 1868, Miles briefly butted heads with General Meade, then commanding the Department of the South (now encompassing North and South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Florida), on using the Fortieth Infantry to enforce order and enable blacks to vote in local and state elections. Miles was determined to deploy the troops, despite—or perhaps because of—the promise of white civilian opposition to their presence.25

Miles took his assignment with the Fortieth seriously and was committed to guarding the rights of black Americans both within his regiment and outside of it. Moreover, looking back from the vantage point of the late 1890s, he recalled the Fortieth with pride for having compiled a “reputation for military conduct which forms a record that may be favorably compared with the best regiments in the service.” Still, it is also clear that Miles put up no resistance in 1869 to being transferred to a white infantry regiment, as was the case for Hazen, too. And one must wonder whether there is any significance in the fact that, in his two published memoirs of 1896 and 1911, Miles failed to mention his service with the Fortieth. One thing is certain, white regiments in the postwar period expected to see more active duty than black ones, given the persistence (or resurgence) of white leaders’ doubts about black men’s military abilities, the USCT’s impressive deeds notwithstanding. Since active duty meant more opportunities for glory and valor—not to mention promotion—it is to be expected that an individual officer’s personal ambition, which someone like Miles had in abundance, could trump even a significant degree of personal support for the new black regiments and take precedence over a professional opportunity to further the higher principles embodied in their formation.26

Still, although the first four commanders of the black Regular infantry units did not remain in place nearly as long as Grierson and Hatch, all six men approached their initial tasks with diligence and energy, starting with the establishment of recruiting stations in likely locations for black enlistees. By early fall, Grierson was recruiting at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, where he also took the opportunity to explore the unfamiliar environment. On October 3, Grierson wrote to his wife about his new location: “One remarkable thing I have noticed,” Grierson informed Alice, was the “millions of grasshoppers fill[ing] the air and in such numbers that they actually darken the sun.” These Kansas grasshoppers, he added, “are impolite and curious enough” to “make their way up under the hoops and skirts of the ladies who are bold enough to promenade among them.”27

While the Tenth began organizing among the feisty grasshoppers at Fort Leavenworth, Hatch’s Ninth Cavalry, as well as the Thirty-ninth and Forty-first Infantry Regiments, organized in New Orleans and Baton Rouge, Louisiana; Hazen’s Thirty-eighth Infantry in St. Louis, Missouri; and Miles’s Fortieth Infantry in North Carolina. Concerned about the quality of the recruits they might draw, commanders and their agents cast their nets wide, Miles sending recruiters as far as the Washington, D.C., area and New York City, and Grierson, who insisted that he “wanted the most intelligent men he could find,” sending Captain Louis H. Carpenter all the way from Kansas to Pennsylvania.28

Although the new regiments began to organize more than a year before the 117th U.S. Colored Infantry finally mustered out and the USCT was completely disbanded, the hope and expectation that some black Civil War veterans might choose to remain in the nation’s military service were abundantly fulfilled. About half of the more than 4,500 enlistees who responded to the first calls to join the postwar regiments were USCT veterans, men like Pollard Cole of Georgetown, Kentucky, who had enlisted in October 1864 in the twelfth U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery, mustered out in April 1866, and now joined the Tenth’s H Troop, for which he served as a farrier—the caretaker of the regimental horses’ hooves and shoes. John Sample of Fredericksburg, Virginia, was another USCT veteran who went on to become a black Regular. Born a slave, Sample had spent two years with the 108th U.S. Colored Infantry doing guard and garrison duty in Kentucky and Illinois. In January 1867, Sample enlisted as a private in the Fortieth Infantry’s Company E. Also a veteran of the USCT, and a former slave, was James W. Bush of Lexington, Kentucky. Bush had served two years with Company K of the famed Fifty-fourth Massachusetts, whose soldiers included Frederick Douglass’s sons Lewis and Charles, and which had bravely stormed Fort Wagner in Charleston Harbor in July 1863, sustaining casualties of over 40 percent. In the course of his service with the Fifty-fourth, Bush rose to the rank of first sergeant and was also wounded quite severely in the leg, possibly at Fort Wagner. As Bush recalled thirty years later, when he enlisted in the Ninth Cavalry in December 1866, “I was yet young,” and had “a great desire to remain a soldier serving this government,” so he kept the information about his injury during the Civil War to himself.29

As recruiters for the new black regiments sought to fill their units with men like Cole, Sample, and Bush, they frequently operated under far less than ideal conditions. Such was the case for the Ninth Cavalry’s recruiters in New Orleans, which was still recovering from the riot that had taken place there in July. Predictably, recruiters in the Crescent City confronted strong but by no means exceptional resistance from local whites who were still smarting from the riot and its implications for social revolution and who considered farm labor the only appropriate work for a freed slave or even a veteran of the USCT. Of course, recruiters were not the only ones who endured challenges in the early days of the new regiments; enlistees suffered gravely, too, and not just from former Confederates’ opposition to their joining the postwar military instead of plying their shovels and hoes. According to the historian Frank N. Schubert, in New Orleans,

Ninth Cavalry recruits found themselves crowded into unsanitary and badly ventilated industrial buildings where steam engines run by slaves had once pressed cotton into five-hundred-pound fifty-inch bales for shipment by sea to textile mills. There the men slept and cooked their meals over open fires while a cholera epidemic raged around them. Nine soldiers died in October [1866], fifteen more in November, and another five in December.

Other daunting and unanticipated obstacles also arose. Five companies of the Fortieth Infantry were shipwrecked on March 1, 1867, and although none of the men died, they lost the bulk of their uniforms, supplies, equipment, weapons, and ammunition.30

White civilian resistance, inadequate facilities, crowded conditions, raging illness, and unreliable forms of transportation were just some of the problems recruiters, officers, and enlistees faced as they worked together to create the new black regiments. They persisted, however, and gradually the regiments came together. New enlistees found themselves engaged in the intensive training necessary to transform them from recruits into soldiers, including, among other things, the most fundamental skills associated with “military courtesy, marching, and marksmanship.” For new cavalry troopers, basic training was even more complicated: in addition to everything else, they needed to learn how to ride without thought, and while fighting with sword and gun. Veterans of the USCT such as Pollard Cole, John Sample, and James Bush undoubtedly provided leavening to the rest of the greener men as they struggled to master the art of war. Veterans also brought with them, and surely shared with their new brothers in arms, the expectations and aspirations they had developed during the Civil War regarding the army as a means to social and political uplift, both for themselves personally and for black Americans generally. As Schubert notes simply, “Black soldiers appreciated the significance of military service as a way to stake their claim to citizenship.”31

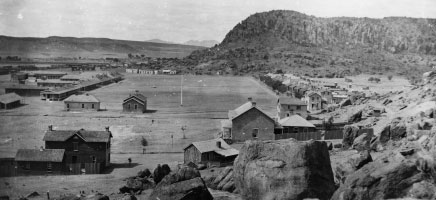

In the spring of 1867, between 250 and 300 of the earliest black Regulars learned that they were about to begin putting their military training into practice, as they received their orders to reoccupy the U.S. army’s post at Fort Davis in Texas, some two hundred miles southeast of El Paso. Built in 1854 in a mile-high desert canyon and surrounded by hills rich in both alpine and desert flora as well as pronghorn antelope, javelina, and lizards, Fort Davis—like the mountains into which the post was nestled—was named in honor of Jefferson Davis, who was secretary of war when the fort was constructed. Before the war, Fort Davis functioned as part of an elaborate network of military installations, staffed with 3,000 soldiers, that extended across much of Texas. During this period, white soldiers of the Eighth Infantry stationed at the fort had provided escort services for frontier settlers passing through the region, guarding them and their goods from raids by the region’s Native inhabitants.32

During the war, Fort Davis—like other Texas posts—was initially occupied by Confederate forces, but it was abandoned as the war’s escalation drew the soldiers east into the heart of the national crisis. For the next five years the post remained uninhabited. In 1867, the federal government decided to restore the now dilapidated fort, reoccupy it, and resume the army’s services protecting white settlers heading west. The first soldiers assigned to perform these tasks were the black soldiers of Edward Hatch’s Ninth Cavalry. Among them was a former slave who would later become particularly well known for the dramatic contours of his two decades of service in the U.S. army, but who was then just a “bright-eyed, hard-nosed, intelligent, well-spoken, and wiry” eighteen- or nineteen-year-old, Emanuel Stance. When the Civil War ended, Stance had initially turned to agricultural labor in the wake of emancipation. In October 1866, however, like so many other young black men in the South, he chose to leave behind the harsh realities of contract labor and sharecropping in favor of the army and its apparent promise, enlisting at Carroll Parish, Louisiana. By the time Stance and the troopers of the Ninth headed west to Fort Davis, he had already been promoted to corporal.33

Fort Davis in the late 1880s. Courtesy of the National Park Service: Fort Davis National Historic Site, Texas.

Stance and his comrades were the vanguard for the thousands of federal soldiers who came west over the next three decades to serve in Texas. Moreover, soldiers from all of the postwar black regiments found themselves stationed at Fort Davis at some point between 1867 and 1885 (the fort was finally taken out of service in 1891), and portions of different regiments frequently overlapped there. Benjamin Grierson, who lived there from 1882 to 1885 when Fort Davis was the Tenth Cavalry’s headquarters, described it to his wife, Alice, upon first visiting it: “The climate is much cooler here than at [Fort] Concho,” another army post, located about three hundred miles to the northeast. “The surrounding mountains make a beautiful picture, look in whatever direction you may.” However, Grierson added, “The post is not located as I would have placed it had I had charge of the matter. It has an appearance of being crowded into or between two hills or mounds and I felt…like taking hold of it and pulling it out and away from a position where…an enemy might with ease take possession of the hilltops and fire down upon the garrison.” Despite Grierson’s concerns, Fort Davis steadily regained its centrality to the nation’s military operations in the Southwest. At the same time, across the state of Texas—which had the distinction of being both a former Confederate and a frontier state—and elsewhere in the Southwest, numerous other forts were soon either reoccupied or built from the ground up.34

The soldiers of the Ninth Cavalry who were posted to Fort Davis in the spring of 1867 began their journey from Louisiana in March, under the able command of the regiment’s lieutenant colonel, Wesley Merritt. Born in New York City in 1834, Merritt had spent much of his youth in Illinois, but he returned to his home state in 1855 to attend West Point, from which he graduated in 1860 and of which many years later, from 1882 to 1887, he would be superintendent. Like the six men originally tapped for the colonelcies of the postwar black regiments, Merritt was propelled steadily upwards thanks to his superior Civil War performance, mostly with the Army of the Potomac; he rose from lieutenant in 1862 to major general of volunteers by war’s end, at which time he was acting as Sheridan’s second in command. It bears recalling that George Custer was the first man to be offered the post that Merritt later occupied. Although he shared Custer’s impressive military record, Merritt brought a significantly more moderate temperament to the position.35

Making a journey that other black Regulars and their white commissioned officers would soon duplicate, the troopers first traveled by steamer to the Gulf Coast town of Indianola, Texas, whose location clearly associated it more with Texas’s Confederate than its frontier identity. Interestingly, in contrast with the virulent expressions of resistance to the presence of black troops to which other former Confederates had steadily given vent, a group of citizens from the town had written to Brevet Brigadier General James Shaw Jr. just a few months before the Ninth arrived in Indianola to offer their strong praise of the USCT’s Seventh U.S. Colored Infantry soldiers, who had served as federal occupation forces there under his command. “The undersigned,” these Texans wrote,

After the surrender of the forces of the Confederate States…in good faith at once gave our allegiance to the Government of the United States, believ[ing] that in doing so there was no necessity for the quartering of troops in our midst. But the authorities thinking otherwise, we have to congratulate ourselves in being so fortunate as to have had your command stationed in our place…. While in many other sections of our state difficulties and discords have been engendered between citizens and soldiers even to the destruction of life and property, in your command at this place everything has been smooth and tranquil, even beyond our most sanguine hopes…for which you will carry with you in your retirement, our sincere and lasting gratitude.36

Given the relative friendliness of the white citizens of Indianola toward black soldiers, it may have been unfortunate that the Ninth did not remain there. Instead, it proceeded to march a distance of about 160 miles to San Pedro Springs, just north of San Antonio, where they remained pending further orders. While they waited, a bloody incident shook the regiment from within, involving E Troop’s black first sergeant, Harrison Bradford of Kentucky. A veteran of the 104th U.S. Colored Infantry, Bradford—like Emanuel Stance—had already demonstrated a number of the skills deemed essential for noncommissioned officer status, including an ability to read and comprehend written orders, and to write out, issue, and enforce orders in turn. As a result, he had been rapidly promoted in his first months of service, first to corporal and then to sergeant.

Although his position afforded him structural authority over other soldiers, like all good officers, Bradford surely knew that the loyalty of one’s subordinates had to be earned every day. And whereas Bradford seems to have done the necessary work to earn his troopers’ fidelity, the white man who was in immediate command of E troop, twenty-three-year-old Lieutenant Edward M. Heyl, had not. Instead, Heyl, himself a Civil War veteran of the Third Pennsylvania Cavalry and the only commissioned officer at that point assigned to E Troop, had revealed himself to be not just a harsh disciplinarian but also a sadistic bigot. Early on he took to abusing the enlisted men, sometimes striking them with his saber even to the point of drawing blood. Already before the regiment had reached San Pedro Springs, Heyl’s cruelty, stoked by his consumption of excessive amounts of alcohol, had become, to many of the enlisted men and clearly to Bradford, virtually intolerable. On April 9, Sergeant Bradford gathered some of the soldiers of E Troop with the intention of confronting Lieutenant Colonel Merritt in an orderly but collective manner and persuading him to intervene on their behalf.37

Bradford and the others had not yet reached Merritt’s quarters when, seeing the men passing his tent, Heyl ordered them to halt and explain their actions. Within moments the two officers were fighting. Shortly thereafter, Heyl fired two shots at Bradford, wounding him badly, but not so badly as to prevent Bradford from lashing out with his sword at another white officer who had just arrived on the scene, and who later died of his wound. Still another white officer approached, quickly pulling the trigger on his revolver and killing Bradford, finishing the job that Heyl had begun. Meanwhile, a number of the enlisted men who came with Bradford had joined in the melee, but as soon as Merritt appeared, they scattered in the direction of their own quarters. Some, indeed, kept right on going in the direction of Louisiana.38

The Heyl-Bradford incident is only one instance of the enduring antagonism black Regulars in the postwar period experienced from some of their white officers, as had also been true for their USCT predecessors. Even the best, most supportive, and most racially progressive commanding officers—like Hatch, Grierson, and Merritt—could not always control the behavior of their subordinates when they were on their own with the enlisted men and noncommissioned officers, and the historical record contains many more instances of similar conflict, including at least one more involving the Ninth Cavalry. In that case, the white commander of K Troop, Captain Lee Humfreville, handcuffed, by pairs, a group of several enlisted men whom he then tied to an army wagon and pulled over four hundred miles across Texas during a nineteen-day period. Along the way, Humfreville sharply limited the men’s rations and also deprived them of the right to warm themselves by the campfire at night. As it turns out, this was only the culmination of a long period of abuse: some days before their long journey from Fort Richardson to Fort Clark began, Humfreville had struck Privates Jerry Williams and James Imes on their heads, first with a carbine and then with a club, before tying them to a tree and taunting Williams with the words “What did you do when you was a slave?” Later, as he marched his handcuffed soldiers toward Fort Clark, Humfreville displayed no hint of mercy. According to one account, “When the troop forded streams, they were dragged through the frigid water with no chance afterward to change clothes or dry themselves,” and when the train stopped for the night, “each had to carry a twenty-five-pound log” and walk around in circles until midnight.” To the army’s credit, Humfreville was court-martialed, found guilty, and dismissed from the service.39

Although both of these incidents involved the Ninth Cavalry, this regiment was not the only one whose enlisted men endured abuse from some of their white officers. In June 1871, near where C Troop of Grierson’s Tenth Cavalry was encamped at the time in New Mexico, privates Luther Dandridge, David Adams, and George Garnett led a rebellion of about eighteen black enlisted men against the troop’s white second lieutenant, Robert W. Price, who seems to have made a name for himself, like Heyl, by treating the black enlisted men poorly, especially when he had been drinking heavily. On this particular day, a clearly inebriated Lieutenant Price heard a group of soldiers laughing and thought they were laughing at him (perhaps because, as the subsequent court-martial revealed, he had been “entertaining” a young civilian boy in his tent). The enraged lieutenant called to First Sergeant Shelvin Shropshire, who was black, and said, “[I]f they are laughing at me, I will give them a dead nigger to laugh at.” According to Shropshire, a semiliterate native of Alabama who went on to serve with the Tenth for thirty-three years, Price then returned to his tent. Soon, however, Shropshire recalled at the court-martial, Price “came back to where I was, and walked down the Picket line near the lower end of the Company street,” discharged his weapon, and fatally wounded Private Charles Smith. Price then turned to Shropshire and said, now “there was something to laugh at.”40

If Lieutenant Price had hoped to subdue the men under his command, he failed. Instead, Dandridge, Adams, Garnett, and others gathered their weapons and threatened to kill him. No doubt hoping to stave off a bloodbath, Shropshire attempted to intervene, demanding that the troublemakers put down their arms and return to their quarters. Asked by the soldiers whether they could have Price arrested, Shropshire informed them that “it was out of an enlisted man’s power, to arrest an officer.” But he urged them to abandon their rebellion. Rather than listening to Shropshire, however, the excited soldiers mounted their horses and proceeded to gallop about the camp, yelling, shooting off their guns, and threatening to stampede the rest of the troop’s herd. Price, meanwhile, tore through the camp brandishing two revolvers and displaying a clear willingness to do more damage. Eventually, though, the uproar came to a close, and the men who had initiated the mutiny came to trial. Thanks in part to Sergeant Shropshire’s testimony, the enlisted men were all found not guilty and returned to duty. What sort of punishment Price received, if any, is not known.

Such incidents demonstrate the implacable racism of some white officers in the postwar period toward the black Regulars they were meant to lead. At the same time, they offer examples of black soldiers like Bradford, who struggled courageously—as the USCT’s soldiers had also done—to stand up for themselves in the face of arbitrary cruelty and injustice. In addition, these events provide occasional examples of how at least some white officers and key figures in the federal government could be counted on to actively denounce such ill-treatment and to support black soldiers’ civil rights and personal dignity. In the Heyl-Bradford case, for example, Lieutenant Colonel Merritt speedily demanded a complete investigation into Heyl’s conduct, after he had already reprimanded Heyl severely. Moreover, although a court-martial found nine of the black troopers involved in that mutiny guilty and sentenced them to death, when he reviewed the court-martial proceedings later, the federal government’s chief of military justice, Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt, pointed out that Heyl’s brutal behavior toward the men had provoked the situation in the first place, and he recommended that Heyl be court-martialed instead and the black troopers’ sentences be reduced.41

In overall command of the military district in which the Heyl-Bradford incident occurred, General Philip Sheridan, too, denounced Heyl’s behavior, concurring with Holt and Secretary of War Stanton that the enlisted men’s sentences should be diminished. Within six months, all of the court-martialed soldiers were released from their confinement. Unfortunately, for reasons that are not known, Sheridan ultimately refused to order a court-martial for Heyl, and before long, because of the army’s rigid system in this period of promoting on the basis of seniority alone, Heyl was elevated to the command of M Troop within the same black regiment, a position he retained until he transferred to the Fourth Cavalry, a white unit, in 1870. While no other racial incidents were recorded after he left the Ninth, Heyl is said to have renamed his horse “Nigger.”42

Beyond the issue of problematic white officers, traveling through and subsequently being stationed on the western frontier meant that black soldiers regularly came into contact with white American frontier settlers and, for soldiers in the Southwest, Mexican civilians, who sometimes welcomed the black soldiers and at other times greeted them with the same sort of suspicion and animosity—even violence—black occupation forces had experienced in the Reconstruction South. A sign of some locals’ resistance to having any direct interaction whatsoever with the black Regulars can be found in the fact that black soldiers serving as stagecoach guards—work they otherwise enjoyed because it offered an alternative to the dull routines of garrison life—were often refused access to return transportation and found themselves having to walk back to their posts. Such inconveniences seem trivial, however, in light of more violent examples. The Tenth Cavalry private John Burnett was killed by the civilian Pablo Fernandez after he attempted to bring a fight under control in the neighborhood just beyond Fort Stockton’s boundaries, not far from Fort Davis. On another occasion, three troopers of the Ninth Cavalry—Privates Anthony Harvey, John Hanson, and George Smallow—were killed for no clear reason by local cattle herders near Cimarron, New Mexico. In cases such as these, it is difficult to exclude racial and ethnic tensions as a motive for murder.43

As in the Reconstruction South, it sometimes was the behavior of the soldiers themselves that provoked local civilians’ rage: in January 1869, Private John O. Wheeler came before a court-martial to face charges that while serving as an escort and guard for the mail service in and around Fort Quitman, Texas, he had become drunk, causing him to be careless with his weapon, steal money and clothing from some local residents, and attempt to rape a Mexican woman, Rufina Humes. Found guilty, Wheeler was dishonorably discharged and confined at hard labor for seven years. Several months later, the Forty-first Infantry’s Charles Jackson was court-martialed for stealing a watermelon from Francisca Ortiz’s husband and, after the husband took it back, attacking him. Francisca reported Jackson to a superior officer, after which Jackson threatened to kill her with a wooden rod. The court found Jackson guilty. In another case, Private Henry Jenkins of the Twenty-fifth Infantry, Company E, was found guilty of stealing a revolver and overcoat from a Mexican citizen living near Fort Davis and beating him up with the help of perhaps a dozen other soldiers and threatening to kill him with an ax. “I was spitting blood for two days” after the attack, Pioquinto Alracon testified at Jenkins’s court-martial. One witness characterized Jenkins as inveterately hostile toward the local Mexican population: “God damn you,” Jenkins reportedly said to a soldier who spoke in Alracon’s defense on the night the incident took place, “you want to take up for the Mexicans, don’t you?” In the end, the court found on behalf of the civilian, and Jenkins was dishonorably discharged, fined, and sentenced to two years’ imprisonment.44

Some interactions between black Regulars and local civilians turned truly ghastly: in January 1869, the Leavenworth, Kansas, Commercial reported that a white man had been murdered at Hays City by three of the Thirty-eighth Infantry’s black enlisted men. In turn, a vigilante committee sought out the alleged murderers, who had already been arrested and were awaiting trial. The vigilantes succeeded, and late one night before the soldiers’ trial could take place, the men were abducted from prison and hanged from the branches of some nearby trees. Fortunately, soldier-civilian encounters were frequently much less noxious than this one, and some black soldiers made strong and lasting connections with their neighbors both during and after the completion of their military service on the frontier. George McGuire, who enlisted in 1869 and was honorably discharged from Fort Davis in 1874, remained in the area working as a civilian teamster for the post. He married a half-Mexican, half-Apache woman, Eduarda Rodriguez, with whom he subsequently had ten children. As one local in the mid-twentieth century described the town in the aftermath of the black soldiers’ arrival there, “Fort Davis became a regular melting pot. Foreigners…married Mexican women; Negroes married Mexican women; and occasionally a white man—who forgot his skin was white…[did, too]…. I knew one Mexican woman who married a white man…while her aunt was married to a very black negro. An Irish girl married a Jew and her brother a Mexican girl. Fort Davis had a regular crazy quilt population.”45

Even as they were striving, and occasionally failing, to get along with local civilians, soldiers on the frontier also had to learn how to get along with one another in close quarters at what were almost invariably remote locations, often hundreds of miles from another post or town. Indeed, court-martial records are replete with stories of conflict within the regiments, even when the soldiers occupied different ranks and sometimes, one suspects, precisely because they did. In a world in which authority overwhelmingly wore a white face, individual black soldiers’ visions sometimes collided when it came to the question of what constituted acceptable behavior between and among black men, who typically shared a past as slaves but who now wielded different degrees of power on the basis of their skills and the effectiveness of their subordination to white officers. Although the black enlisted men in Sergeant Bradford’s company had respected and been loyal to him, such was not always the case. In December 1868, for example, Private Edmund Durotte and First Sergeant Felix Olevia of the Ninth Cavalry’s H Troop came close to killing each other at Fort Quitman after Olevia demanded that Durotte return money he had borrowed, and then threatened Durotte with a saber for refusing to do so. According to testimony given in the January 1869 court-martial, Durotte, who insisted that he owed Olevia nothing and, furthermore, that he resented Olevia’s attentions toward his (Durotte’s) wife, at this point “picked up a carbine and threw it” at Olevia, who dodged it. Then, testified Olevia, “the accused ran back and picked up an axe…and attempted to strike me with it.” Pulling rank, Olevia ordered Durotte to the guardhouse, but Durotte refused to go until he was forced to do so by two other soldiers Olevia had ordered to escort him. At the court-martial, Durotte was found guilty of attacking Olevia, but in the end the finding was disapproved and his sentence reduced.46

An equally dangerous disagreement took place in July 1869, also at Fort Quitman, between Private John Baptiste of the Ninth Cavalry’s I Troop and his company’s Corporal Taylor, which similarly led to a court-martial. On this occasion, Baptiste was driving a team of unruly mules carrying a load of wood when he stopped briefly at his quarters to get a drink of water. Apparently Taylor, who had given Baptiste the job to do in the first place, thought the private was neglecting his duty, and confronted him shortly after Baptiste got the team moving again. According to Baptiste, he never heard Corporal Taylor order him to stop the team, which he characterized at the trial as “wild,” “green,” and hard to control. In contrast, Taylor said Baptiste heard but refused to stop the team and, instead, cursed Taylor saying, “You are the damndest fool I ever saw, to come down and talk to a man because he stopped in his quarters for water,” adding, “I’ll be God damned if I stop my team.” It is impossible to know who was telling the truth; what is clear is that one or more of the mules promptly ran right over Corporal Taylor. Although he does not seem to have been badly injured, the court found in Taylor’s favor and ordered Baptiste dishonorably discharged.47

Black enlisted men on the frontier who shared the same rank got into fights with each other, too, as was the case with Privates Robert Scott and Reuben Ash of the Tenth Cavalry’s D Troop. In December 1869, Ash appeared before a court-martial convened at Fort Sill to answer the charge that he had tried to kill Scott after the two had gotten into a dispute over a pair of trousers, which Ash claimed Scott stole. Ash might have succeeded in shooting Scott dead but was prevented from doing so by Sergeant William West, who seized Ash’s loaded carbine just as he pulled the trigger and sent the charge into the air. In the end, Ash was found not guilty, and Scott came before another court on the charge of stealing Ash’s pants (among other things). He, too, was found not guilty.48

In contrast with Ash and Scott, who escaped punishment for their dangerous squabbling, Private William C. Alexander of the Tenth Cavalry’s L Troop was found guilty of the charge that he did “follow, attack, assault, and beat with rocks and stones, the person of Private William H. Miller,” also of L Troop, “without just cause or provocation.” Apparently, Alexander had determined to steal Miller’s pay from him; when he attacked Miller, Alexander injured him so severely that Miller could no longer perform his duties as a soldier. Found guilty, Alexander was dishonorably discharged and sentenced to imprisonment at hard labor for eighteen months.49

Disagreements among black Regulars arose from a host of causes and circumstances; one common source of tension was the men’s conflicts over women, with whom contact was clearly (and no doubt frustratingly) limited, especially at remote frontier locations. In May 1871, at Fort Quitman, Private James Fisher and Sergeant James W. Bush (the USCT veteran mentioned earlier), both of the Ninth Cavalry’s I Troop, came to blows after Bush and another of the regiment’s noncommissioned officers, one Sergeant Gordon, found Fisher hanging out at the home of a Mexican woman who lived near the fort and with whom Gordon claimed to have a personal relationship, which the woman herself denied. Hoping to avoid trouble, Fisher returned to camp, but the following day, the still angry Gordon provoked a dispute with Fisher while Fisher was in the company kitchen attempting to complete his various chores for the day. Soon Bush also became involved, calling Fisher a “black son of a bitch” (Bush, of course, was also black) and knocking him to the floor. To defend himself, Fisher grabbed an ax that was hanging on the kitchen door, hitting Bush “a light lick,” or so he later claimed. Yet another black noncommissioned officer in the regiment, Sergeant Andrew Carter, grabbed the ax from Fisher, but in doing so banged himself with the handle over his left eye. The potentially tragic fight came to a close with minimal injuries. In a subsequent court-martial, Fisher was found guilty of a series of charges pertaining to the events, though how he was punished for his offenses is not known.50

Negotiating the complex interpersonal dynamics of the mixed racial and ethnic environment in which they found themselves, while at the same time learning about military life, discipline, and order, proved more difficult for some new black Regulars than for others, though probably no more so overall than for white soldiers. Not long after his enlistment in 1867, Private William Alexander of D Troop, Tenth Cavalry, was court-martialed and sentenced to ten days’ punishment—sitting on the head of a barrel in clear view of his fellow soldiers from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. each day—for selling his government-issued overcoat to buy a jug of whiskey. At Fort Gibson in Indian Territory, Private John Burns of Company C, Twenty-fifth Infantry, paid a stern price for demanding a meal at an irregular hour: when Burns attempted to get the company cook, Private James Jones, to provide him with his midday meal after the others had already eaten, Private Jones rightly refused. In response, Private Burns cursed the cook, brandishing a razor and threatening to hurt him. A court-martial found Burns guilty of “conduct to the prejudice of good order” in the regiment and sentenced him to four months’ confinement and forfeiture of pay for the same period. At Fort Brown, Texas, Private John H. Williams of the Ninth Cavalry’s G Troop simply wandered away without leave from his post as sentinel over the troop’s horses while the horses were quietly grazing. Rather than spending time with the horses, Private Williams seems to have sought some time—“one hour, more or less”—with one of the regiment’s laundresses. When he came before a court-martial three months later, Williams offered no defense of his actions and was found guilty, fined four months’ pay, and sentenced to confinement at hard labor for that same period. Being lax in guarding a regiment’s animals from thieves was a persistent problem, which some new soldiers seem to have had ongoing difficulty recognizing: in September 1869 at Fort Sill, in Indian Territory, Corporal Robert Anderson of the Tenth Cavalry (B Troop) had similarly failed in his charge to guard the troop’s horses, allowing the sentinel on duty to walk away from the herd and take up a leisurely conversation with him under a tree.51

Clearly, as they moved out on to the western frontier, soldiers in the new black regiments necessarily devoted considerable time and energy to working out the details of living peacefully and productively together and with their white officers and the local civilians. Undoubtedly, the inevitable isolation and frequent boredom of frontier service made interpersonal relations more difficult, especially when combined with the challenges of coming to grips with military discipline and military life generally. Some new soldiers in the black regiments never did manage to adjust, and found their way out at the end of their terms of service or through dishonorable discharges. Desertion also offered a potential means of escape, although as Senator Benjamin Wade had noted in 1866, with regard to the USCT troops serving on occupation duty, the desertion rates of black Regulars were significantly lower than the rates for white soldiers during this period.

Still, some recruits took what seemed (but rarely proved to be) the easy way out. Such was the case with the Tenth Cavalry’s Privates James Reed and Frank Wilson, who were caught trying to board an eastbound train at Hays City, Kansas, in late May 1868. In July 1869, Private Wesley Abbott also tried to desert the Tenth Cavalry; when he was caught at Leavenworth City, Kansas, a year later, he pleaded guilty. Echoing the complaints, if not the attempted solution, of other black Regulars, Abbott insisted that it was the harsh treatment he had received at the hands of his black noncommissioned officers that had driven him off. In a written statement he prepared in conjunction with his August 1870 court-martial, Abbott declared, “I enlisted with the firm determination to do my duty and serve my time but was so brutally treated by the non commissioned officers…for no offense whatever…that I determined to escape from their clutches.” It is quite possible, of course, that Abbott was just not prepared for the rigors of military discipline. In any case, he was found guilty, and in the end paid a high price for his decision to run away. Although he pleaded for a light sentence, the court dishonorably discharged him, denied him all back pay, and imprisoned him at hard labor at Fort Leavenworth for a year, during which time a weight was attached to his left leg with a five-foot-long chain. The court also demanded that Abbott be branded on the left hip with a 1.5-inch-long letter D, a brutal punishment to which white deserters from the army were also subjected.52

When Private Jackson Askins of E Troop, Ninth Cavalry, was brought before a court-martial at Fort Clark and charged with desertion, he explained that his decision to abscond was rooted in his inability to get along with a superior officer, in this case, his troop’s white commander, one Captain Hooker. According to Askins, Captain Hooker had more than once informed him, for whatever reasons, “I do not want you in my company.” Finally, Askins had decided to take Hooker at his word, leaving his troop and his regiment behind and taking a job in Austin. It was only after several months that Askins was arrested, at which point Hooker, who had known all along where to find him, preferred charges. At his trial Askins insisted that over the course of his three years of service he had “endeavoured to be a good soldier and never did the idea of deserting enter my head…[until] I was forced by my Company Commander [and] positively ordered by him to leave the company and encampment.” Only then did he leave, he continued, knowing that if he did not, Hooker “would make it so hard for me that it would be worse than dying to serve out the balance of my time in the service.” The unsympathetic court found Askins guilty and dishonorably discharged him, adding a sentence of two years’ confinement at hard labor, with forfeiture of pay during that period. But a subsequent review of the court’s proceedings and the evidence led to Askins’s exoneration—presumably on the basis of corroborating material pertaining to Captain Hooker’s active dislike for him—and he was returned to duty.53

As it turns out, though, just about a month later, Private Askins was in trouble again, this time for “deliberately and with malicious intent” setting loose two of E Troop’s horses, which he then allegedly allowed “to run at large, thereby endangering their safety and that of the other horses in the stables,” and also for using “violent, profane, abusive, and obscene language” when speaking with Private McElroy McGill. McGill was on duty guarding the E Troop’s stables and demanded that Askins go and retrieve the horses. According to Askins, E Troop’s commander—most likely still Captain Hooker—had told him to leave the horses alone. Then, when Private McGill told him to go get them, Askins weighed his options and initially decided to do as his company commander had told him. At this point, Private McGill tried to strike a bargain: if Askins would admit to having let the horses loose in the first place, McGill would not report Askins to Hooker. Once again Askins weighed his options and finally decided to “confess.” Askins was arrested immediately. At his court-martial, Askins was found guilty, fined, and sentenced to prison. As happened in his previous trial, however, a subsequent review overturned the verdict and sentence and restored Askins to duty. Private Askins may well have had difficulty staying out of trouble, but it seems that on balance those who took ultimate responsibility for judging his behavior determined that his weaknesses as a soldier were less significant than his strengths.54

It must be noted that the complicated challenges black enlisted men faced in adjusting to postwar military service at places like Fort Davis and elsewhere on the frontier were compounded by their regular exposure to devastating illness and injury. Soon after Lieutenant Colonel Merritt and the first four troops of the Ninth Cavalry arrived, for example, Fort Davis experienced a medical crisis as a result of rampant scurvy and dysentery. That August, Texas and Louisiana had also been struck by yellow fever, and dysentery with its accompanying diarrhea remained frequent throughout the years the fort was in operation, exacerbated by periodic smallpox outbreaks. Some soldiers, like Private Silas Jones of Grierson’s Tenth Cavalry, fell sick repeatedly: over the course of his thirty years in the army, Jones’s medical record indicates that he suffered from a host of complaints, including acute diarrhea, headache, “catarrh,” mumps, colic, orchitis (a testicular inflammation), constipation, tonsillitis, bronchitis, rheumatism, and neuralgia, among other conditions. None of this, however, interfered with Jones’s determination to remain in the service, or with his being recognized upon his discharge as “an honest and faithful soldier.” Black Regulars, like soldiers in all times and places, also suffered from a variety of sexually transmitted diseases, including gonorrhea and syphilis. For some, like Private Lewellen Young, who was discharged on account of “syphilitic mania” and committed to a government asylum in Washington, D.C., disease brought a painful end to their military careers, if not their lives.55

If staying healthy was a perennial problem at the widely scattered western posts where black Regulars were stationed, so was sustaining a sufficient supply of rations, not just for the soldiers but also for the cavalry horses and livestock on which the men, in turn, depended. According to one source, at Fort Davis a cavalry horse required fourteen pounds of hay and twelve pounds of grain each day. As for the men, they subsisted largely on the same sorts of rations that had sustained their Civil War predecessors, including hash, a stew known unappealingly as “slum gullion,” baked beans, hardtack, salt bacon, coffee, bread, and beef. On a typical day at Fort Davis, the baker George Bentley and others prepared at least 560 loaves of bread for the soldiers stationed there.56

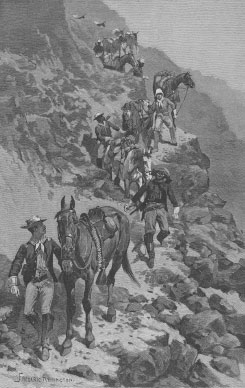

“Marching on the Mountains,” by Frederic Remington. Originally published in Century Magazine in 1889.

Keeping isolated posts such as Fort Davis supplied with even the nutritional basics was an ongoing challenge, and learning to endure shortages was, for both animals and men, a necessity. Hardly unrelated was the matter of maintaining good mounts for the cavalrymen, which sometimes posed serious problems: in October 1868, Benjamin Grierson received a letter from Lieutenant Henry Alvord, the Tenth Cavalry’s adjutant, who had been inspecting the portion of the regiment stationed at Fort Arbuckle in Indian Territory. Although he had few complaints about the troopers themselves, Alvord expressed considerable concern to his commanding officer about the horses: “I shall condemn at least fifteen horses,” he wrote, “and leave several for another time. Seven have died since you were here.” Six months later Grierson wrote to his wife, Alice, from Camp Wichita in Kansas, indicating that problems similar to those that Alvord had addressed earlier remained to be solved: “Having no forage I have had to keep the Cavalry horses out 12 to 13 miles from Camp, grazing night and day in order to keep them alive, or a portion of them rather as many have died for want of food.” In addition to the horses, Grierson worried about the manpower drain that having the horses so far from camp entailed. “Have had an officer and about 50 men constantly in charge of herding them,” he wrote.57

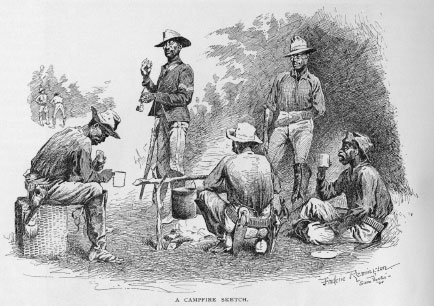

“A Campfire Sketch,” by Frederic Remington. Originally published in Century Magazine in 1889.