5

Insult and Injury

[N]ever did a man walk the path of uprightness straighter than I did, but the trap was cunningly laid and I was sacrificed, effective June 30, 1882.

—Henry O. Flipper (1916)

JOHNSON WHITTAKER WAS BORN A SLAVE IN AUGUST 1858 IN CAMDEN, South Carolina, where his mother, Maria, served as a personal attendant to Mary Chesnut, the famous elite Southern diarist. After the Civil War, seven-year-old Whittaker, his mother, and his two brothers remained in Camden and attempted to carve out a new life for themselves in freedom. Like Henry Flipper’s parents, Maria Whittaker was determined that her children would become educated, so she sent her sons to a local school that had been set up by white Northern missionaries. Young Whittaker studied there for five years. Later, he went to the Camden public school before undergoing private tutoring to prepare him for the recently integrated University of South Carolina’s entrance examinations. These he passed when he was just shy of sixteen, in July 1874.1

While studying at the University of South Carolina, Whittaker came to the attention of Richard T. Greener, the first black graduate of Harvard College and now a professor of mental and moral philosophy at the university. In 1876, Greener identified Whittaker as a strong candidate for an appointment to West Point, and on his recommendation, Congressman Solomon L. Hoge, who had also nominated James Webster Smith, nominated Whittaker to fill the vacancy created by Smith’s dismissal. Late in August, Whittaker, who was now eighteen years old, five feet eight, and slight of build, arrived at the academy, where he soon took and passed the entrance examinations. For the next ten months, until Flipper’s graduation, he and Flipper, West Point’s only two black cadets, shared a room but did not, it appears, have a particularly close friendship.

Like the other black cadets who had preceded him, Whittaker experienced white resentment from the moment he arrived on campus. Early on, a white cadet from Alabama struck him in the face for no particular reason. Refusing to retaliate directly—perhaps under guidance from Flipper—Whittaker nevertheless informed school authorities what had happened. They responded, encouragingly, by court-martialing and then suspending the white cadet for six months, which meant that he had to repeat the school year. Whittaker, no doubt, was pleased with the initial results of having resisted fighting back with his fists. However, at least some white West Pointers seem to have interpreted Whittaker’s restraint as cowardice (though they had also considered Smith’s boldness an unacceptable form of aggression). Still, the rest of Whittaker’s first year passed uneventfully, and although he was not at the top of his class academically, he was not at the bottom, either.2

After Flipper graduated in the summer of 1877, Whittaker briefly had the company of another promising black cadet, Charles A. Minnie of New York. But as Virginia’s John Washington Williams had done in 1874, Minnie failed his midyear exams and was dismissed. Back in New York, Minnie reported to a journalist that “from the very moment he entered” the academy he had been “subjected constantly to a galling ostracism” by the white cadets, although he added—echoing Flipper’s lenient attitude—that he had enjoyed relief from his peers’ hostility in the form of the professors’ and officers’ “considerate and gentlemanly treatment,” which “allowed no distinction of race or color to alter their bearing toward any student.” Apparently believing that Minnie’s criticism of the academy cadets might reflect poorly on his protégé, or have unpleasant consequences for him, Richard Greener wrote a letter of rebuttal to Minnie’s accusations, asserting that Whittaker, unlike Minnie, had “won the respect of his teachers and fellow cadets” alike, and declaring, “Scholarship, gentlemanly conduct, and a punctilious regard for veracity will, in my humble judgment, enable any really meritorious colored youth to graduate from West Point.”3

It is not clear how, in the end, Greener measured Whittaker’s overall performance at the academy on the scale that he himself devised. Whittaker’s fundamental academic abilities seem to have been sufficient, but he still ended up having to repeat his third year because of purported inadequacies in the classroom. Even with the advantage of taking classes a second time, Whittaker continued to struggle. Moreover, although he made friends with two of the academy’s black servants and some black locals in the nearby town of Highland Falls, he had no one in his own position with whom to endure the white cadets’ relentless hostility and harassment. In his Bible, Whittaker underlined passages expressing his loneliness.4

Then, in early April 1880, Whittaker’s West Point experience took a dramatic turn: at the 6:00 a.m. roll call on the morning of April 6, Whittaker failed to appear. Responding to his absence, Major Alexander Piper sent the cadet officer of the day, George R. Burnett, to Whittaker’s room. Getting no answer when he knocked on the door, Burnett entered. There he found the cadet lying to all appearances unconscious on the floor, wearing only his underclothes. Although Whittaker’s head was resting on a pillow, his arms and legs were tied together with the same material that was used for cadets’ belts, and his legs were also tied to his bed. Whittaker’s body and face were covered with blood, and there was also blood all over the room, “on the center of the mattress, on the wall above the middle of the bed, and on the floor,” as well as on the door and on some material that was lying on the floor near Whittaker. Even the pillow under Whittaker’s head was bloody, and near the bed a blanket and comforter showed traces of blood as well. Also disturbing was the discovery of a blood-stained club, some burned pieces of paper, a broken mirror, some clippings of hair that seemed to come from Whittaker’s head, a pocket knife with the blade open, a small pair of scissors, and a bloodied handkerchief with the name tag removed. Fearing that Whittaker was dead, Burnett—after asking two cadets to stand guard—raced from the room to get help.5

When Burnett found Major Piper and told him what he had discovered, Piper rushed to the room, bringing an orderly with him. Checking Whittaker’s pulse, he was surprised to find it normal, and another cadet informed Piper that he had just seen Whittaker’s toe move. Obviously, Whittaker was not dead, but the extent of his injuries remained unknown, and in an attempt to get a better look at them, Burnett opened the tightly drawn curtains. He then cut the bindings on Whittaker’s hands and legs. Whittaker remained motionless except for some shivering, apparently caused by the coldness of the room. At this point Major Piper sent his orderly for the academy’s physician, Dr. Charles Alexander. While he waited, Piper directed Burnett and several other cadets who had gathered in the interim to join him in looking around the room for clues about what had happened.6

When Dr. Alexander arrived about ten minutes later, he examined Whittaker, who in Alexander’s judgment was not even unconscious. Alexander then attempted to elicit a response from Whittaker, whose ear was bleeding, by shaking and pinching him and asking him questions. Although Whittaker mumbled vague responses, such as “Please don’t cut me,” he did not seem to revive. To the doctor, though, a vague flickering in one of Whittaker’s eyelids and the appearance of discomfort when tapped hard on the chest suggested that the cadet was faking. Meanwhile, Lieutenant Colonel Henry M. Lazelle, the commandant of cadets at the academy, made his way to Whittaker’s room. Lazelle was the first official to hear Alexander’s theory of Whittaker’s deceit, upon which the lieutenant colonel commanded Whittaker to “get up” and “be a man.” At first Whittaker did not respond, but soon, thanks to additional shaking by Alexander, Whittaker opened his eyes and sat up.7

Shortly thereafter, Whittaker rose to his feet and limped across the room to his washbasin, where he began to scrub the blood from his face, even as Dr. Alexander attempted to examine and dress his wounds. At the same time, Whittaker began to speak about his ordeal: how he had been attacked in the middle of the night by three men, at least one of whom was wearing cadet gray; how he had been “seized by the throat and choked until [he] was almost suffocated” and “struck on the left temple and on the nose with something hard” how he had been “completely overpowered” and thrown to the floor, his earlobes slashed by one of the men who claimed to want to “mark him like they do hogs down South,” and cut large patches of hair from his head; and how he had struggled but been unable to resist, and then was tied up and left to suffer, but not before a pillow was placed under his head. According to Whittaker, his attackers had departed with the admonition that he remain silent about what had happened, and with words of assurance to one another that surely now Whittaker would abandon his studies at West Point. Too weak and frightened to cry for help, Whittaker had tried to free himself but, finding it impossible to do so, had lain on the floor until he either fell asleep or passed out.8

Whittaker’s account was extensive, detailed and, as it turned out, unshakable. But it appears that Dr. Alexander and some others in the room had already made up their minds that he had fabricated the whole situation, and nothing in Whittaker’s story then or later dissuaded them. When West Point Superintendent John M. Schofield, a Civil War veteran, arrived on the scene, he remained only long enough to have a look around, confirm that Whittaker was alive, and order Lazelle to initiate a full investigation. A number of cadets eagerly offered to help with the investigation, if only to prove that no white West Pointer was capable of committing such a horrible crime. Meanwhile, Dr. Alexander ordered Whittaker to the hospital, where he changed some dressings and asked Whittaker to explain again what had happened. Whittaker repeated his story, and Alexander sent him away. A little later that morning, in conversation with yet another white officer, Whittaker added one crucial detail he had previously omitted: that he had received a threatening note the day before he was attacked. When asked to produce the note, he did so promptly. Then he went off to class while the investigation, which included a thorough examination of his room and all the evidence that had been found there, got underway.9

The investigation Lazelle oversaw over the next two days contained features that seem most irregular, including ordering that Whittaker’s room be cleaned and reorganized immediately and all of his soiled and stained clothing be washed. In the end, Lazelle’s report fingered Whittaker as the culprit. According to him, Whittaker had written the threatening note, staged the attack, inflicted his own wounds, cut off his hair, bound himself up, and bound his legs to the bed. He had then remained prone on his barracks room floor until it became necessary for him to feign unconsciousness after his absence at roll call drew notice. Clearly, Lazelle—who was hardly alone in his perspective—did not think it was possible for white cadets to have attacked Whittaker or, having attacked him, to lie about such deeds, although he was quite comfortable accusing the black cadet of deception. He recommended that Whittaker be given the opportunity to withdraw outright from the academy, or undergo either a court of inquiry—not unlike a grand jury investigation in the civil justice system—or a court-martial. Having read the report, Superintendent Schofield summoned Whittaker to his office and offered him the three choices. Whittaker requested that his story be heard by a court of inquiry. On April 8, Schofield issued the necessary orders, and on April 9 the court convened.10

In the days that followed, news of the incident at West Point traveled quickly beyond the bounds of the academy itself, in no small part because Superintendent Schofield agreed to a multitude of interviews about the case, in which he repeatedly expressed his suspicions about Whittaker’s veracity. Newspapers like the New York Times and the Washington Post, as well as the military’s own media organ, the Army and Navy Journal, picked up the story, which they followed for the many weeks to come. As a result, the Whittaker case “almost immediately became not simply the story of one cadet’s plight but the account of West Point’s treatment of [all] black cadets” and, by extension, of white Americans’ treatment of black Americans more generally.11

As early as April 10, the Army and Navy Journal was weighing in on the case. At first, it posited two possible explanations for what had happened: either Whittaker had been attacked precisely as he claimed—and presumably on account of his race—by three men, at least one of whom was a fellow cadet; or he had fabricated the entire scenario to compensate for his academic inadequacies, in the hope that his wounds might land him in the academy hospital, prevent him from taking his exams, and buy him “another year of grace.” Eventually the Journal published a third possible explanation: that Whittaker was essentially a coward who had “tamely submitted to an outrage which, in the case of any other cadet would be classed as an indignity,” and then “quietly went to sleep and slept comfortably through reveille, and until awakened by the surgeon,” at which point he found it necessary to devise a cover story.12

Other newspapers and some members of Congress, however, continued to believe that Whittaker was not only not a coward but was entirely innocent, the victim of a terrible, racial crime. These supporters argued that the academy was to blame on account of its failure to deal with its internal racism. The Journal, in turn, insisted that it was unfair to blame the white cadets—whom they, like Lazelle, considered upright and moral—for their ingrained racism, which was, after all, only a pale reflection of the racism found in the society at large. “[W]e think it unjust to hold the academy responsible for the existence of prejudice between the races that was implanted by parents and friends in the early years of life, which is far more deeply rooted in the public mind to-day than it is at West Point.” The article even went so far as to cite some favorable comments about race relations at the academy from Henry Flipper’s recently published autobiography, The Colored Cadet at West Point. At the same time, the Journal also published an angry letter to the editor, signed by one “Ebbitt,” who crudely likened Whittaker to Dred Scott as an unattractive “historical character” and suggested, paradoxically, that the case had been concocted to serve the agenda of members of Congress who supported the abolition of the Military Academy altogether.13

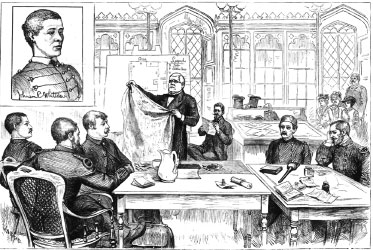

“The West Point Outrage,” a scene from the Whittaker court of inquiry. Originally published in Harper’s Weekly in 1880. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

At the academy, Whittaker’s court of inquiry dragged on. Also dragging on, it bears noting, was his painful isolation. Indeed, after the second day of the court of inquiry, it was determined that Whittaker should not even attend the sessions but should return to his classes, cutting him off from the proceedings and confining his knowledge of them to the newspapers or mentions of them in the halls. Even the Army and Navy Journal had to admit that Whittaker conducted himself during this stressful period with “nerve, coolness, self-possession, and defensive power that excited astonishment amongst all, and enthusiasm amongst those who still believe him innocent.” Meanwhile, Whittaker communicated by letter with family and friends, especially Richard Greener, now dean of the law school at Howard University, who also came to visit. But in important, fundamental ways, Whittaker was alone.14

As for the case itself, as the weeks passed, it grew more and more convoluted, as different theories were brought into play about what had happened and about what the evidence presented at the court of inquiry meant. Over time, too, increasingly prominent figures in the army and the government became involved. Indeed, as early as April 14, only five days into the proceedings, no less a figure than the army’s adjutant general, E. D. Townsend, arrived under orders from the secretary of war, Alexander Ramsey, to observe. Townsend promptly submitted to a newspaper interview, in which he expressed his own suspicions that Whittaker had indeed faked the attack.15

At the end of May 1880, the court of inquiry completed its business and issued its report, identifying Whittaker in no uncertain terms as guilty of having concocted the events under investigation. Superintendent Schofield immediately recommended that the black cadet be dismissed and perhaps also court-martialed. Surely Schofield yearned to bring an end to the incident and get the public spotlight off the academy as quickly as possible. But doing so was hardly simple. For one thing, many people who had found themselves wrapped up in the case still insisted that the court of inquiry’s conclusions were questionable and that further discussion—about the events of April 6 and about the situation for black cadets at West Point generally—was required. These interested observers loudly demanded a new investigation, and some urgently called for Schofield’s replacement as West Point’s superintendent by someone more sympathetic to blacks’ rights, such as Oliver Otis Howard. Meanwhile, Whittaker, who had been in the midst of his crucial year-end examinations when the court of inquiry issued its report, proceeded to fail his philosophy test.16

In this tense situation, an article entitled “Caste at West Point” appeared in the June 1880 issue of a highly influential popular journal, the North American Review. The article’s author, Peter S. Michie, was a professor of natural and experimental philosophy at the academy, and much of his article was devoted to defending West Point against what he perceived to be the perennial assertions about its elitism and its function as an agency dedicated to producing military aristocrats. To the contrary, Michie argued, “[T]here is neither caste nor aristocracy now, and never has been, among the cadets. Men arrange themselves here, as elsewhere, by sympathy, by similarity of tastes, by ability, intelligence, and aptitude in their profession.” Michie also devoted considerable attention to the fine moral record of the academy’s nearly three thousand graduates to date (notably, he ignored the moral blemish represented by hundreds of cadets’ demonstration of disloyalty to the nation during the Civil War). Wrote Michie, “The one sure, strong safeguard of the Military Academy is the degree in which its pupils hold sacred their word of honor. They will not lie or steal.” An army whose officers were without a strong moral core, Michie believed, was an army doomed to fail in any conflict. Fortunately for the U.S. army, West Point’s graduates—at least the white ones—presumably suffered from no such character weakness.

Michie then turned to the question of black men’s presence at the academy. Having just made a case for the lack of “caste” at the school, he nevertheless expressed doubts about whether, as he put it, “it was wise to endeavor to solve the problem of the social equality of the races at that time and at this place.” Looking back over the years since James Webster Smith had first matriculated, Michie posited that things might have gone reasonably smoothly for the black cadets as a whole if they had only been more intelligent and—especially in the case of Smith—less “irascible” and “vindictive.” Smith, Michie insisted, “came prepared to make trouble” indeed, “the isolation that was his lot would have been the fate of any white cadet under similar circumstances,” though one is hard-pressed to imagine how similar to Smith’s a white cadet’s circumstances could possibly have been. In any event, according to Michie, it was Smith’s academic failures, not his race, that did him in. Turning to the other black cadets who had been appointed to the academy since Smith—including Flipper, the only one who had managed to graduate—Michie expressed the opinion that although they all seemed to have “excellent memories,” to a man they had “displayed a marked deficiency in deductive reasoning.”

As for the Whittaker case, Michie argued, quite stunningly, that rather than serving as an example of the academy’s ongoing failure to embrace black cadets, it demonstrated how much more welcoming toward them the academy had in fact become over the past decade. After all, had not some of the white cadets expressed a measure of “human sympathy” toward Whittaker in the aftermath of his fabricated ordeal? More broadly, Michie insisted that none of the black cadets, including Whittaker, had ever been subjected to the “slightest indignity,” nor had they been “hazed” or “deviled.” To Michie, this was a detail of enormous importance, especially given that such good behavior on the part of white cadets toward black ones was really more than one had a “right to expect in this transition period,” given the “almost universal prejudice” toward blacks that most white cadets had learned from their families and communities. Michie concluded, with an apparent attempt at magnanimity, “Let the authorities send here some young colored men who in ability are at least equal to the average white cadet, and possessed of manly qualities, and no matter how dark be the color of the skin, they will settle the question here as it must be settled in the country at large, on the basis of human intelligence and human sympathy.”17

Michie wrote his article before the final decision in the Whittaker court of inquiry was handed down. In contrast, by the time his West Point colleague George L. Andrews, a professor of French, published his own article, “West Point and the Colored Cadets,” in the November issue of the International Review, the court of inquiry’s report had been published. In light of the report’s conclusion that Whittaker had faked the attack, Andrews—who ironically had the same first and last name as the man who served with dedication as the black Twenty-fifth Infantry’s colonel from 1871 to 1892—expressed even more vehemently than Michie his support for the academy, his faith in the fair treatment the black cadets to date had received, and his unwillingness to endorse any demand that white cadets should exceed the standards of race tolerance that their parents, friends, and communities manifested. At the same time, Andrews insisted, “Any assertion that either the authorities of the academy or the corps of cadets have intentionally pursued a course designed to get rid of colored cadets is wholly unwarranted….”18

In his own annual report that fall, Superintendent Schofield addressed the Whittaker case along with the larger questions of whether blacks should be admitted to the academy and whether they could succeed either academically or socially there. Schofield declared that, to date, the black cadets’ “social relations to their fellow-cadets” had been strained at best. Moreover, echoing Andrews and Michie, he asserted that “military discipline is not an effective means of promoting social intercourse or of overcoming social prejudice. On the contrary, the enforced association of the white cadets with their colored companions, to which they had never been accustomed before they came from home, appears to have destroyed any disposition which before existed to indulge in such an association.” In order for black and white cadets to get along better at the academy, race relations across the nation would have to improve first.

Schofield went on to heap additional blame on the black cadets: the struggles of some, at least, had been the predictable consequence of their “bad personal character.” He added, for good measure, that “to send to West Point for four years competition a young man who was born in slavery is to assume that half a generation has been sufficient to raise a colored man to the social, moral, and intellectual level which the average white man has reached in several hundred years. As well might the common farm horse be entered in a four miles race against the best blood inherited from a long line of English racers.” That Whittaker’s case had become a source of crude humor not just to Schofield but also far beyond the walls of the academy is indicated by the letter that Alice Grierson, wife of the Tenth Cavalry’s colonel, wrote that fall to their son Charles, who had begun his studies at West Point the same year as Henry Flipper but had graduated after him: “Fanny Monroe gave a masquerade party last week,” Alice wrote. “Lt Leavell said he wanted to personate Cadet Whittaker, and wanted to borrow your cadet uniform for the purpose. I loaned it to him, and he came in to show us how he looked, which was hideous. He had his face blackened, and then painted red in the most savage style.”19

As discussion on the merits of his case continued, Whittaker found himself subject to orders issued on the last day of December 1880 by the nation’s president, Rutherford B. Hayes, to come before a court-martial in connection with the April events. Although by now Whittaker must have expected the court-martial to produce the same verdict as his earlier court of inquiry, it did serve one key purpose: postponing his dismissal from the academy. The trial took place in New York City beginning on January 20, with the Fifth Infantry’s General Nelson A. Miles presiding. The black Philadelphia newspaper, the Christian Recorder, was optimistic: “Miles,” the paper declared, “believes in fair play for every man,” and as a result, “the general opinion” was that the Whittaker case would be evaluated with impartiality. Two charges were brought against the defendant: “conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman” and “conduct prejudicial to good order and discipline.”20

Although the testimony phase of the court-martial lasted four months, virtually no important new evidence or information was introduced, and public interest, perhaps predictably, gradually diminished. Then, on June 12, the Washington Post reported that the Whittaker court had “dissolved” and the judges had dispersed without immediately publicizing their verdict, which still required review by the army’s judge advocate general (Brigadier General David G. Swaim), the secretary of war (Robert Todd Lincoln), and the newly inaugurated president (James A. Garfield). Subsequently, when the report of the court-martial became public, it revealed that Whittaker had indeed been found guilty on both counts, although it appears that six of the ten members of the court had signed a recommendation for clemency on the basis of Whittaker’s “youth and inexperience,” which would have eliminated the fine and the term of confinement required by his conviction but would not have revoked his discharge. Even more important: nine months later, in March 1882, President Chester Arthur (who took office following Garfield’s assassination) disapproved the court’s findings and sentence completely on the basis of procedural errors during the court-martial.21

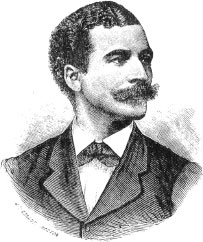

Major General John M. Schofield, ca. 1865. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

In practice, though, none of these details made much difference: Whittaker’s failure on his philosophy exam meant that he would be dismissed from the academy anyway, fulfilling the negative expectations Michie, Andrews, Schofield, and others had openly expressed. When news of the court’s original decision first appeared, the Washington Post declared that it was Whittaker’s character that had undone him, not his race. “Army officers are not prejudiced against Whittaker on account of the color of his skin,” the paper declared. “Many, however, consider him ignorant and low in all his instincts.” In contrast, however, the Post offered warm praise for Henry Flipper, who “gets along swimmingly with his brother officers, all of them white men, of the Tenth Cavalry.” Flipper, the paper insisted, “is gentlemanly, intelligent and brave—qualities that are bound to command respect, be the color of their possessor’s skin what it may.” Ironically, within weeks of the Post’s declaration of its support for the “gentlemanly, intelligent and brave” Tenth Cavalry’s black second lieutenant, Flipper found himself under unusually severe confinement in a “sweltering six-and-one-half-by four-and-one-half-foot cell” in the guardhouse at Fort Davis, Texas, pending a court-martial of his own.22

Looking back over Flipper’s brief span as a commissioned officer in the Tenth Cavalry, one finds no evidence to suggest that his military service would come to such a critical point so quickly, at least not on account of flaws in his performance as a soldier and an officer. His commanding officer Grierson noted that, since joining the regiment, Flipper had been “constantly on duty, serving as a company and staff officer with marked ability and success.” He was, moreover, an honest man, whose “veracity and integrity” had “never been questioned” and whose “character and standing, as an officer and a gentleman,” had been absolutely spotless. “I can testify to his efficiency and gallantry in the field,” Grierson declared, pointing out that Flipper had “repeatedly been selected for special and important duties,” which he had “discharged…faithfully and in a highly satisfactory manner.” The fact that Flipper was the only black man to have completed officer training at West Point and achieved commissioned officer status in the U.S. army, Grierson acknowledged, meant that he served under particularly heavy pressure. And yet, Flipper had “steadily won his way by sterling worth and ability, by manly and soldierly bearing, to the confidence, respect and esteem of all with whom he has served or come in contact.” Having learned of Flipper’s arrest at Fort Davis, Grierson—who was himself then about three hundred miles away at Fort Concho—urged his superiors to offer Flipper a court of inquiry rather than consign him immediately to a court-martial, but he informed his wife that he thought the chances of his request being granted were slim.23

Flipper’s military record with the Tenth Cavalry clearly bears out Grierson’s confidence: during his first months of active duty, while at Fort Sill, Flipper had served for four months as acting commander of the regiment’s G Troop during the troop captain’s absence, and supervised road construction and the laying of telegraph lines in the area. During a stint at Texas’s Fort Elliot, he worked as a surveyor and cartographer and also boldly led an investigation into illegal ammunitions sales that resulted in the arrest, court-martial, conviction, and three-year confinement of a white quartermaster sergeant, an outcome that surely caused resentment among some of his army officer colleagues, but not in Grierson. Returning to Fort Sill in 1879, Flipper devised and oversaw construction of a drainage system designed to eliminate the mosquito-breeding ponds of standing water that frequently plagued the fort, in order to improve the health of the soldiers posted there. This system, known as Flipper’s Ditch, continues to be utilized today to control area floodwaters.24

The guardhouse at Fort Davis where Lieutenant Flipper was held in August 1881. Courtesy of the National Park Service: Fort Davis National Historic Site, Texas.

Not all of Flipper’s duties were related to his skills as an engineer: while posted at Fort Concho, Flipper also actively participated in the army’s attempt to subdue the Apache leader Victorio, on one occasion riding almost a hundred miles in less than twenty-four hours—roughly twice the distance considered reasonable under the best of conditions—to convey important information to Grierson, then stationed at Eagle Springs. Flipper collapsed from exhaustion after he completed this task: “I had no bad effects from the hard ride till I reached the [commander’s] tent,” Flipper recalled years later. But “when I attempted to dismount, I found I was stiff and sore and fell from my horse to the ground” and proceeded to sleep “till the sun shining in my face woke me next morning.” Then, on July 30, 1880, Flipper and his company of black Regulars engaged with Victorio’s band for five hours, during which battle three of the soldiers serving with Flipper died. As it turned out, this was to be Flipper’s only combat experience.25

Clearly, Flipper’s record of excellent service in the Tenth Cavalry did not exempt him from criticism and accusation, however, and when he came before the judges at his Fort Davis court-martial in the fall of 1881, he faced two charges: embezzlement of federal funds and, like Whittaker, “conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman.” Flipper had been the commissary of subsistence—the officer in charge of the fort’s food supplies—since his arrival there the preceding fall, and according to the specifications in the case, between July 8 and August 13, 1881, he had falsified commissary records and mishandled accounts, resulting in a discrepancy of almost $4,000, which he seemed unable to explain satisfactorily. Testimony before a panel of eleven officers began on November 1 and lasted for about a month, during which time numerous local whites paid tributes to his fine character. “The more I saw of him, the better I liked him,” declared J. B. Shields, a Fort Davis merchant. “I have always found him to be [a] straightforward man, of good character,” testified another, Joseph Sender. “I have never seen anything in Lieutenant Flipper’s conduct but what was becoming of a perfect gentleman,” insisted W. S. Chamberlain, a watchmaker in town. At the same time, however, the prosecution brought forward a number of witnesses who presented contrary evidence, including their key witness Colonel William R. Shafter, now in command of the white First Infantry but previously—for more than a decade—the lieutenant colonel of the black Twenty-fourth.26

Since Shafter had taken command at Fort Davis in March 1881, there had been indications that his long-term willingness to command black troops did not necessarily reflect a comparable willingness to see black men themselves in command, at least not as commissioned officers. Or perhaps Shafter simply did not care for Henry Flipper. In any case, upon his arrival at Fort Davis, Shafter had acted quickly to curtail Flipper’s responsibilities. In addition to his assignment as commissary of subsistence, Flipper had been serving for several months as acting assistant quartermaster. “I had charge of the entire military reservation,” he wrote later, “houses, water and fuel supply, transportation, feed, clothing and equipment for troops and the food supply.” Shafter, however, replaced Flipper in this post with a white officer from his own First Infantry. He also seems to have warned Flipper that his days as commissary of subsistence were numbered.27

Reassigning army staff in this way was hardly unusual when a new commander took charge, and Flipper’s removal as assistant quartermaster may have been nothing more than the logical consequence of Shafter’s desire to select an officer of his own regiment for the position. Moreover, at Flipper’s court-martial Shafter insisted that he had found the young black lieutenant, so far as he “could observe, always prompt in attending to his duties,” which Flipper had performed “intelligently and to my entire satisfaction.” Shafter maintained that his reasons for replacing Flipper arose only from his belief that Flipper was a cavalry officer who “ought to be assisting the other cavalry officers in performing their duties in the field” rather than doing administrative work at the fort. But Flipper himself believed that the new post commander was targeting him, especially after he received warnings from others in and around the fort that he should do his best to stay on the famously prickly Shafter’s good side. “I had been cautioned,” Flipper recalled later, “that the commanding officer would improve any opportunity to get me into trouble, and although I did not give much credit to it at the time, it occurred to me very prominently when I found myself in difficulty…. [H]e had long been known to me by reputation and observation as a severe, stern man.”28

Precisely how much Flipper failed in his quest to engender and sustain Shafter’s goodwill, how much Shafter’s “goodwill” was inflected with deeply held racist notions, and how much Flipper simply bungled his job as commissary of subsistence, can never be answered with certainty. The complicating features in Flipper’s situation, and the court-martial case itself, are too numerous, including the fact that another of the prosecution’s key witnesses was the white first lieutenant Louis Wilhelmi, who not only was close to Shafter but also had been at West Point when Flipper was there; he had not, however, succeeded in graduating, for which he may have felt some personal resentment.29

Also complicating the situation, according to Flipper and others, was the interracial friction at the post that Flipper’s friendship with a young white woman, Mollie Dwyer, seems to have stimulated. Dwyer was the unmarried sister-in-law of A Troop’s Captain Nicholas Nolan (Nolan’s wife, Annie Dwyer, was Mollie’s older sister). Since the time that Mollie Dwyer and Flipper had met when he was on assignment with A Troop at Fort Sill in 1878, the two had been seen out riding together on many occasions. Indeed, for a time at Fort Sill, Flipper and Captain Nolan both had rooms in the officers’ quarters, though there is no evidence that the relationship between the young black lieutenant and his captain’s sister-in-law—who lived with Nolan and his wife—developed into an active, reciprocal romance during this period. Still, Flipper and Dwyer were clearly fond of each other. Things changed, however, once they were all at Fort Davis. A white officer and Civil War veteran with more substantial financial resources than Flipper—Lieutenant Charles E. Nordstrom—became interested in Dwyer, too. He even purchased “a luxurious riding buggy,” apparently to lure Dwyer’s attention away from Flipper, an affront that Flipper, understandably, resented. The rivalry between the two lieutenants appears to have become quite bitter and may well have fostered divisions among the other soldiers and officers posted there. One thing is certain: the Flipper-Dwyer-Nordstrom affair did not make Flipper’s life at Fort Davis easier, nor did it help ensure his long-term success as an officer in the U.S. army.30

In the course of Flipper’s court-martial, in the fall of 1881, Flipper insisted, with respect to the first charge against him, “I have never myself nor by another appropriated, converted, or applied to my own use a single dollar or a single penny of the money of the Government or permitted it to be done, or authorized any meddling with it whatever.” That said, it seems clear, on the one hand, that Flipper—who had received no formal training for his administrative assignment—had indeed mishandled commissary money. At one point, rather than in the quartermaster’s vault, he was storing some of the funds he had collected in a locked trunk in his quarters, to which Lucy Smith, a post servant, had access. He also left checks and cash lying about his room. On the other hand, most of the $4,000 originally believed missing was located, and the balance of a few hundred dollars, which Flipper in desperation temporarily tried to conceal by writing a check of his own on a nonexistent account, was quickly covered by donations from members of the community who enthusiastically rallied to his support and some of whom were among the witnesses who later testified on his behalf.31

It is also clear that the officers (including Shafter) who might have provided Flipper with more guidance, training, and oversight in his position had failed to do so. Between May 28 and July 8, 1881, Shafter had, for unknown reasons, stopped performing regular reviews of Flipper’s accounts, which allowed Flipper’s errors and misjudgments to multiply. Unfortunately, rather than admitting that he had made errors, Flipper clumsily tried to cover his tracks, most likely out of a sense of panic exacerbated by his awareness that the eyes of the nation were upon him, especially in light of the recent events surrounding Whittaker. “I indulged,” Flipper later wrote, “what proved to be a false hope that I would be able to work out my responsibility alone, and avoid giving him [Shafter] any knowledge of my embarrassment.”32

But it was precisely Flipper’s duplicity regarding the accounting problem that led to his downfall. For his part, Shafter seems to have been convinced that Flipper had been actively embezzling, rather than just being sloppy. But even if clumsiness and inexperience lay at the root of Flipper’s bad accounting practices, Shafter felt strongly that Flipper’s failure to come clean about his mistakes represented a failure of honor. As a result, his biographer Paul Carlson writes, Shafter was “unwilling to forgive his subaltern” and “struck back with all the considerable weight of his position as post commander.”33

Flipper’s court-martial at Fort Davis ended in early December 1881, almost exactly six months after Whittaker’s court-martial had ended in New York City. Unlike the Whittaker court-martial, however, Flipper’s yielded a split verdict. That Flipper was found not guilty of embezzling federal funds implies that the judges recognized that he was careless rather than criminal. He was, however, found guilty of “conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman” on account of his behavior once he originally became aware of the discrepancies in the books that his blunders had produced. Like Whittaker’s, Flipper’s career with the U.S. army was over. Six months after the case closed, following a review by Judge Advocate General Swaim, Secretary of War Robert Lincoln, and President Arthur, Flipper was dismissed. And thus, by mid-June 1882, the U.S. army was once again without a single black commissioned officer, and West Point was once again without a single black cadet.34

Humiliated by their shared experiences with the army, both Flipper and Whittaker nevertheless went on to live impressively productive lives. Flipper’s life in particular bore out the sort of confidence in him that Benjamin Grierson had expressed on account of his intelligence, competence, and integrity. From Fort Davis, Flipper moved briefly to El Paso, then took up work as a surveyor for a group of American mining companies in Mexico, where he became fluent in Spanish. He later worked as a cartographer before being hired as chief engineer for the Sonora Land Company of Chicago. In 1887 Flipper opened his own civil and mining engineer office in Nogales in the Arizona Territory, where he also edited a local newspaper. From 1890 to 1892 he worked as chief engineer for the Altar Land and Colonization Company in Nogales, in 1893 becoming a key witness in a land claims case in Nogales that pitted 700,000 acres’ worth of white settlers’ claims against those of a group of land speculators who were also lawyers; the judge ultimately found in favor of the settlers. As a result of this case and all of his previous work, Flipper was hired as a special agent for the U.S. Justice Department’s Court of Private Land Claims and, according to the historian Quintard Taylor, for the next eight years “researched the Mexican archives, translated thousands of documents, surveyed land grants throughout southern Arizona, and prepared court materials. In the course of this work he translated and arranged, and the Justice Department published, a collection of Spanish and Mexican laws dating from the sixteenth century to 1853.” In his final report about Flipper’s work for the Justice Department, U.S. Attorney Matthew G. Reynolds offered nothing but praise. “During the seven years Mr. Flipper was connected with this office,” Reynolds wrote, “his fidelity, integrity and magnificent ability were subjected to tests which few men ever encountered in life. How well they were met can be attested by the records of the Court of Private Land Claims and the Supreme Court of the United States.”35

In 1901 Flipper took a job as an engineer for the Balvanera Mining Company in Mexico, which later became part of the Sierra Mining Company. Transferring to the company’s El Paso office in 1912, Flipper remained an employee of Sierra until 1919, that year traveling to Washington, D.C., to become a translator and interpreter for the U.S. Senate’s Committee on Foreign Relations. In 1921, he accepted a position as a special assistant to the Interior Department’s Alaska Engineering Commission, and in 1923 he relocated to Caracas, Venezuela, as a consultant of the Pantepec Oil Company, over the next seven years aiding in developing Pantepec’s oil-rich land holdings. Flipper’s remarkable career finally ended after the stock market crash in 1929 severely damaged Pantepec’s fortunes. He then spent a year in New York before returning in 1931 to the city of his youth, Atlanta, where—now retired—he moved in with his brother. Flipper died in Atlanta in May 1940, at the age of eighty-four.36

As for Johnson Whittaker, after his discharge from West Point, he initially took his case to the public, giving speeches in Buffalo, Baltimore, and Georgia about his West Point experiences. Subsequently, he moved to Charleston, South Carolina, where he accepted a job at the Avery Normal Institute, an all-black vocational and teacher-training school, and also took up the study of law. Whittaker was admitted to the South Carolina bar in 1885, and in 1887 he opened what quickly developed into a successful law practice in Sumter. Unlike Flipper, who remained single, Whittaker married in 1890 and had two children. In 1900, he moved his family to Orangeburg, South Carolina, gave up his law practice, and took a position teaching at the all-black Agricultural and Mechanical College—the same school, ironically, where James Webster Smith had served as commandant of cadets after his dismissal from West Point back in the 1870s. Eight years later, Whittaker moved his family again, this time to the new state of Oklahoma, where he taught at an all-black high school in Oklahoma City and ultimately became its principal. In 1925, the family returned to South Carolina. Whittaker died there in 1931.37

One way to understand the stories of Whittaker and Flipper in connection with West Point and the U.S. army is simply as chronicles of individual failure. But to read these stories—or those of other black American men, such as James Webster Smith and Michael Howard—purely as tales of individual failure is a mistake. For to do so ignores the fact that, just like the enlisted men in the USCT during the Civil War and early Reconstruction, and just like their counterparts in the postwar black regiments on the western frontier, Flipper, Whittaker, Howard, and Smith—their own personal flaws and weaknesses aside—were struggling to succeed as soldiers and as citizens under the extraordinary weight of the history and persistence of American racism.

Moreover, it cannot be denied that the timing of Flipper’s and Whittaker’s shared humiliation in the early 1880s raises important questions about the larger social and cultural context in which they—and the black Regulars generally—were operating, and how the dynamics of American race relations may have been spiraling downward in the second decade after Appomattox. Put another way, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that Flipper’s and Whittaker’s experiences reflect, at least in part, the renewal or intensification of white resistance to blacks’ progress in the military, in conjunction with the ongoing deterioration in race relations nationally. It would seem that, by the beginning of the 1880s, black men’s dedicated service on behalf of the national agenda had yielded only limited and tentative rewards, rather than the sort of richly construed and deeply meaningful citizenship that Frederick Douglass had envisioned for black soldiers in 1863 and that they, no doubt, envisioned for themselves. If Flipper’s and Whittaker’s cases are any guide, the social and political rewards that black men could hope for in return for their military service were diminishing, and the obstacles they, like black Americans generally, faced on the path to full and meaningful citizenship were intensifying.

As we have already seen, those who had hoped in the postwar period that the nation’s justice system would steadily and consistently make the case for black Americans’ full rights as citizens were destined to experience much disappointment and frustration. In addition to the events and issues discussed earlier, it bears noting that in 1873, even as Flipper was just beginning his career at West Point, the U.S. Supreme Court had declared, in what were collectively known as the Slaughterhouse Cases, that the crucial Fourteenth Amendment protected only those rights of citizenship “that owed their existence to the federal government,” such things as “access to ports and navigable waterways” and “the ability to run for federal office, travel to the seat of government, and be protected on the high seas and abroad.” All other rights of citizenship “remained under state control.” Subsequently, in 1876, in the case U.S. v. Cruikshank, the justices overturned the convictions that a lower court had obtained against three whites in the 1873 Colfax, South Carolina, riot, added new language declaring that the Fourteenth Amendment “only empowered the federal government to prohibit violations of black rights by states,” not by individuals, and reiterated that “the responsibility for punishing crimes by individuals rested where it always had—with local and state authorities.” In 1878, in the case Hall v. DeCuir, which arose out of a claim by a black woman that she had been denied the right to sit in a Louisiana steamboat cabin reserved for whites, the Supreme Court declared segregation on public transportation legal. Then, in its 1882 decision in United States v. Harris, the Court voided the 1871 KKK Act. A year later, following its consideration of a series of racial discrimination cases that had arisen in Kansas, Tennessee, Missouri, and New York—known collectively as the Civil Rights Cases—the Court determined that neither the Civil Rights Act of 1875 nor the Fourteenth Amendment could provide protection against discrimination by individuals. By the early 1880s, in short, as the U.S. army’s officer corps was sealing its doors against black candidates, the Supreme Court was laying the foundation for Jim Crow.38

In the face of these and other disturbing developments, on New Year’s Day 1883, a group of approximately fifty distinguished black leaders—including Frederick Douglass, his two sons who had served with the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts, and the USCT veteran and Medal of Honor winner Christian A. Fleetwood—gathered in the nation’s capital to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. According to one contemporary account, the guests “represented a who’s who of two generations of black politicians, civil servants, journalists, writers, professors, ministers,” and, not least, black veterans. In the speech he gave at this event, Douglass “urged vigilance at the flame of black freedom and justice.”39

The following September, just a short time before the Supreme Court handed down its decision in the Civil Rights Cases, a much larger gathering of black leaders took place at Liederkranz Hall in Louisville, Kentucky. Here, at the National Convention of Colored Men, more than two hundred men from twenty-seven states came together to discuss the political, social, and cultural situation facing black Americans and to consider the merits of blacks’ ongoing loyalty to the Republican Party, the party of Abraham Lincoln. In the words of the Los Angeles Times—itself a testament to the success of the nation’s postwar consolidation and expansion—the meeting was “a notable gathering of representative men of the race.” Some observers described the gathering, which like its predecessor in January included many USCT veterans, less favorably: the Louisville convention, predicted the New York Times sourly on September 9, “bids fair to be a vent for jealousies and grievances.”40

When he was asked why such a convention had been organized, Douglass, who served as chair and also gave the keynote speech, answered simply, “because conventions in this free country are the usual instrumentalities through which great bodies of men make known their wants, their wishes, and their purposes.” Asked why black men deemed it necessary to come together on the basis of their race specifically, Douglass pointed out, “We are, whether we will it or not, in some sense a separate class from all other people of the country, and we have special interests to subserve and special methods by which to subserve them.” As he had done in the nation’s capital at the beginning of the year, Douglass urged black Americans to continue to demand their rights as citizens in the face of any and all emerging obstacles: “Now that we are free, we must, like freemen, take the reins in our own hands and compel the world to receive us as equals…. The negro’s road downward is made easy, but his struggle upward is obstructed from every quarter.”41

The Louisville gathering, which lasted about four days and was occasionally tumultuous, produced an official eleven-point statement in which the delegates began by expressing appreciation for the abundant legislation that had been passed in the preceding twenty years on black Americans’ behalf. Signers of the statement noted, however, that many of the new laws had quickly been reduced to meaninglessness, especially in the South. There, “almost without exception,” the conventioners pointed out, “the colored people are denied justice in the courts, denied the fruits of their honest labor, defrauded of their political rights at the ballot box, shut out from learning trades, cheated out of their civil rights by innkeepers and common carrier companies, and left by the States to an inadequate opportunity for education and general improvement.” Notably, the conventioners did not directly address the situation of blacks seeking U.S. army officer training, and indeed, that summer, John Hanks Alexander of Helena, Arkansas—a freeborn man who had attended Oberlin College before matriculating at West Point—had succeeded in passing the academy’s entrance exams. (In 1887, a decade after Flipper, Alexander became only the second black man to graduate from West Point, after which he served for seven years with the Ninth Cavalry before dying in 1894 of natural causes.) But the delegates nevertheless assailed the “distinction between white and colored troops in the army” as “un-American and ungrateful.” White men, the delegates observed, “can enter any branch of the service, while colored men are confined to the cavalry and infantry services,” a distinction that was “carried into the navy as well.” Most likely because they believed that the desegregation of the army’s regiments would lead directly to black men’s exclusion from the service entirely, they did not express any negative sentiments about blacks’ units being race-based.42

In their official statement, the delegates also condemned the collapse of the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company, which they termed “a marvel of our time.” Established by the federal government in March 1865, the bank initially served as a depository for the savings of USCT soldiers but soon was opened to other black Americans as well. Its goal, in the words of the historian Carl Osthaus, was “to mold ex-slaves into middle-class citizens” by developing and encouraging among them “concepts of industry and thrift,” as if such concepts were novelties for people who had lived lives of extreme deprivation for more than two centuries. The bank also offered a limited number of new employment opportunities for blacks, including both Christian Fleetwood and Frederick Douglass, the former as a clerk and the latter as the bank’s president for a year. For a time, branches of the bank across the South did well, highlighting to the freedpeople and other observers “that progress was being made along the economic path ‘up from slavery.’” But severe mismanagement (though not by Douglass, Fleetwood, or any of the other black officials of the bank), along with what Osthaus calls “the perversion of a philanthropic crusade into a speculative venture,” from which “white speculators and real estate dealers” in Washington profited, led to the bank’s collapse. The bank took with it almost three million dollars of the savings of its depositors—many of them still black veterans—only about half of which was ultimately repaid over the course of the next forty-odd years.43

The 1883 convention in Louisville decried the corruption that had led to the bank’s collapse, which the delegates perceived as only one example of the many ways in which white Americans were continuing to obstruct black progress. In the end, the convention, writes the historian David Blight, “threw a bleak picture of African American conditions at the feet of the nation.” Four years later, the frustrations of the men gathered in Louisville were reiterated when, in early August 1887, four thousand mostly black American civilians joined three hundred USCT veterans—led by those of the Fifty-fourth and Fifty-fifth Massachusetts Regiments—in what amounted to the first official black Civil War veterans reunion and “the largest known assembly of black former soldiers and sailors after the Civil War.” In his welcoming speech for the two-day event, former second lieutenant James M. Trotter of the Fifty-fifth Massachusetts, one of the rare black men to have been granted an officer’s commission during the war, reminded his fellow veterans that their history “was different from that of the rest of the army. You went forth to the war not knowing anything about the future,” although “you knew that if you were captured you would be given no quarter.” Trotter praised the courage and sacrifices of the men who had gathered on this occasion: “I see before me today,” he declared, “men from all over…who were determined never to give up; men who were bound to fight until death.”44 Similarly, General A. S. Hartwell, the white former commander of the Fifty-fifth Massachusetts, praised the veterans for their unique contributions to the nation’s survival. “I know well,” said Hartwell, “that when you enlisted in the war, you did what a white man could not do. You knew that the flag under which you fought…waved over enslaved millions of your own people. And yet you went to work.” Later on that first day, James Trotter returned to introduce the black Sergeant William H. Carney, who “on the day of the terrible assault on Fort Wagner carried his country’s flag triumphantly over the parapet amid the deadly storm of shot and shell.” Still later, Trotter introduced Colonel W. H. Hart, the white former commander of the USCT’s Thirty-sixth Connecticut Infantry, who expressed his enormous pride at having had the opportunity of “serving and commanding one of the best colored regiments ever mustered in [to] the service” of the U.S. army.45

Former Second Lieutenant James M. Trotter, in civilian dress, ca. 1880. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Colonel Hart spoke of his pride, but he struck a different note as well, bringing his thoughts to a close by pointing out that “what the colored man wanted was justice, and that he was going to get it.” The second day of the reunion was in fact dedicated to considering the conventioners’ sense of black Americans’ progress toward justice and full citizenship, as well as their ongoing responsibilities to the nation. By the end of that day, like the black men who had gathered in Louisville four years earlier, the black veterans in Boston produced a statement reflecting on “the present deplorable condition of the colored people in the South,” who still accounted for more than 90 percent of the blacks in the United States as a whole. They cited black Americans’ persistent “subjection to mob violence and deprivation of the right of suffrage.” Like the delegates at Louisville, the former soldiers and their allies in Boston “declar[ed] it to be the duty of the Government to remedy these evils until the colored man shall have equal protection under the law with his white brethren.” They also noted that, despite the military service of almost 200,000 black men in the army and navy during the Civil War, as yet no monument acknowledging their sacrifices—or, one could add, those of the black Regulars on the postwar frontier since Appomattox—had been constructed anywhere in the nation. Later that year, the USCT veteran George Washington Williams sought to remedy this injustice when he introduced a bill in Congress for a monument to USCT veterans like himself. The bill failed.46

As the men who had gathered in Boston in August 1887 prepared to return to their homes, it was clear that the sacrifices of black soldiers during the Civil War to save the nation, and of their counterparts on the frontier in the late 1860s, 1870s, and 1880s to complete the nation’s postwar agenda, had yet to yield them their full rights as citizens. And the situation was only getting worse. Just a year before the Boston reunion, the New York Age had declared that “high handed tyranny in the administration of the law” remained a “favorite tenet” in the “creed of Southern white men in their dealings with colored men,” and it urged black men, “[S]tand up for your rights! Strike back! Yell when you are struck! Show that you know how to give as well as to take blows!” Later that year, the same paper noted that the U.S. Congress was, for the first time in a quarter century, “without a colored congressman in either house.” Soon Mississippi would become the first Southern state to rewrite its state constitution explicitly to exclude black men from voting.47

It bears noting that throughout the period under consideration, efforts on the part of black Americans to lay claim to citizenship through military service had been underway outside of the U.S. army as well, including in the context of state and local militia. Black citizen-soldier units had begun to form soon after the Civil War, and some were already in existence in places like Ohio and Rhode Island by the time congressional legislation in July 1870 ensured their right to exist. Once the federal law was passed, black militia forces took shape steadily in most of the states of the former Confederacy, in part to provide defense to black and white Republicans confronting white Democratic resurgence. Predictably, white Democrats responded with vehemence, opposing the creation of black militia units “as a challenge to white domination” and doing everything in their power to undermine them. Still, black militia units persisted, even in the face of the federal government’s 1877 removal from the South of its occupation troops. In 1878 there were still approximately 800 black citizen-soldiers in North Carolina. In 1882 there were 352 in Texas, and in 1885 there were 1,000 in Virginia. These militias gave their members opportunities for leadership and social status and an expansive example of blacks’ assertion of citizenship.48

As it turned out, in connection with this movement, in December 1880, just as Whittaker’s court of inquiry was concluding at West Point, none other than Christian Fleetwood had participated in the founding of what was called the Washington Cadet Corps. Although many of the black militia units created after the Civil War were led by white officers, some, including Fleetwood’s Washington Cadet Corps, defied the traditions of the USCT and the postwar black Regulars and selected black men as officers. Starting with one company, Fleetwood, with the rank of captain, worked to increase the corps’ size and strength, and before long it included four well-supplied companies of soldiers, all of whom paid for their own uniforms and equipment. The corps also had a twenty-five-piece brass band. In 1883, Fleetwood, as the men’s commander, was awarded a large and impressive silver trophy—the gift of a wealthy local merchant—for the corps’ performance in competition with other black citizen-soldier organizations in the District of Columbia.49

In 1887, the same year the black veterans met in Boston, the Washington Cadet Corps officially became the Sixth Battalion of the District of Columbia National Guard. (The Seventh and Eighth Battalions, also black, were added shortly thereafter.) At that point, Fleetwood received a commission from President Grover Cleveland as major of the Sixth Battalion. Some years later, Captain John Bigelow Jr. of the Tenth Cavalry—a white officer in that black regiment who was clearly familiar with the work, abilities, and accomplishments of the black Regulars—described Fleetwood’s National Guard battalion, and Fleetwood himself, in highly positive terms. Bigelow wrote, “[H]is battalion impressed me very favorably by its proficiency in drill and the soldierly deportment of its officers and men individually. I am satisfied that Christian A. Fleetwood has the faculty of controlling men, and the talents and attainments necessary for making a good volunteer officer.” Meanwhile, Fleetwood worked diligently and successfully to persuade local black schools to adopt a cadet system of military training and drill for male students, an example of his persistent faith in the principle that military service smoothed the path to citizenship and social equality. Unlike the corps, the high school cadets, who met weekly to train with Fleetwood as their instructor, were armed only with wooden guns.50

High School Cadet Corps at the M Street High School in Washington, D.C., 1895. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

In January 1889, a large number of black Washingtonians signed a testimonial recognizing Fleetwood’s “patriotic services to the Union during the late civil war” and his charitable and benevolent work in the community in the years since he had mustered out. The signers credited Fleetwood with the “high standing for proficiency achieved by the Colored Militia of the District of Columbia, both from a Military standpoint, and as reflecting credit upon the race.” That same month, in a letter to a “Mr. Arnold,” Frederick Douglass, now seventy-one years old, enthusiastically referred to Fleetwood as “our gallant friend and fellow citizen.”51

It is true that, like the creation of the black Regular regiments in the U.S. army in 1866, the incorporation of Fleetwood’s black Washington Cadet Corps into the previously all-white District of Columbia’s National Guard in 1887 represented a positive development, a sign that in some circles, in some settings, black men’s continuing contributions to the nation’s work as soldiers had the potential to improve their social status, civil and political rights, and opportunities vis-à-vis white men. But this sign of progress, too, was undercut by other simultaneous and disheartening developments. As has already been pointed out, although sanctioned by federal law, postwar black militia units struggled in the face of white efforts to disband them, and the Washington Cadet Corps was no exception. Within a year after the corps became part of the D.C. National Guard, trouble surfaced. In 1888 the Washington Bee, a black newspaper, noted Fleetwood’s failure to receive an invitation from the white commanding officer of the D.C. National Guard, the Civil War veteran General Albert Ordway, to the formal opening of the guard’s new headquarters (indeed, none of the black officers in the guard received invitations). In response, Ordway explained that the event had been “a purely personal and social affair,” not unlike a “private dinner,” and that the members of the army, navy, and militia forces who had been invited were simply his friends. Although the Bee article quoted Fleetwood as refusing to comment negatively on the incident—Ordway was, after all, his superior officer—the newspaper nevertheless declared Ordway’s behavior “a palpable insult” and urged “all colored officers” to “show that they resent the insult offered them by this man who is too small to be great.” Subsequent articles in the Bee and other newspapers continued the discussion, in at least one case suggesting that more serious trouble between the races in the D.C. guard lay ahead. One white paper warned of what would happen if a black officer was in charge of white soldiers. “It would surprise no one if the white soldiers should come to a sudden and untactical halt and refuse to play until the colored ranking officer was superseded by a Caucasian. This is regarded by many as more than possible—it is highly probable.”52

In the face of these developments, one black newspaper grumbled, “The negro is good enough when danger threatens the republic, but when there is quiet restored and the feasts commence, the negro militia can come as servants or some other [menials] but not as guests.” In the weeks ahead, the Bee accused Ordway or someone in his inner circle of encouraging Congress, in stark contrast with its previous generosity, to suddenly slash its appropriation for the D.C. guard. Cutting the guard’s budget, the Bee predicted, almost certainly meant eliminating the guard’s black members. And indeed, within a couple of years, the Bee’s prophecy came true. In early March 1891, General Ordway issued orders eliminating the black battalions completely, citing the absence of congressional funding to support them. As Ordway put it, only these black battalions could be removed “without disturbing the regimental organizations of the Guard” as a whole.53

Some companies of militiamen within the three black battalions had been mustered out as early as 1889, the year prominent black Washingtonians signed their testimonial to Fleetwood praising him for his excellence as a commander and a citizen. Now the rest were to be dismissed. Ordered to turn in their uniforms and equipment, the black guardsmen gathered at the O Street Armory to return “every bit of property belonging to the United States which had been issued” to them. Then, having completed this painful duty, they assembled to hear Fleetwood solemnly read Ordway’s order and then give a speech, in which he insisted that they adhere to the order “no matter with what regret.” The men listened silently, their discipline unruffled. Some weeks later, Fleetwood—who as a faithful soldier had sworn himself to silence until the situation was resolved—finally spoke up in a letter to the editor of the Washington Bee. He noted that some black men had, in fact, already been readmitted to the guard, thanks to the “prompt, intelligent, and courageous action” of unnamed (presumably white) supporters who, in the wake of Ordway’s orders, had expressed outrage at the men’s dismissal. These supporters’ advocacy had, it appears, persuaded President William Henry Harrison to countermand Ordway’s order and reinstate at least some black militiamen. Still, Fleetwood no longer wanted to be a part of the D.C. guard, nor did he feel bound to “obey a man proven so unworthy of respect.” He announced his resignation.54