1964–1965

“What is it like to be the little princess, the woman who has fulfilled the whispered promise of her own books and of all the advertisements, the girl to whom things happen? It is hard work.”

—Joan Didion, “Bosses Make Lousy Lovers,” Saturday Evening Post, January 30, 1965

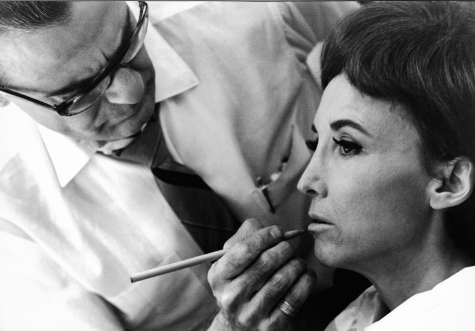

Helen looked ten years younger on television, and she was the first to admit why. On TV, she wore a wig, false eyelashes, powder, two kinds of rouge, lipstick, eyeliner, pencil, and shadow. The great thing about radio was that it was all about the voice, and Helen’s voice was made for radio—or rather, she remade it for radio. Soft and silky, it glided across the airwaves like aural lube. Callers could rant about her ruining American morals, hosts could call her names, but they never got her to raise her voice. “I’m kind of outspoken and controverseeyal,” she would coo in agreement.

When Joe Pyne, a former marine turned talk show host known for his confrontational interviewing style, called her a “terrible woman” for giving girls explicit instructions on how to have a lunchtime affair with a married man, including advice on what kind of lingerie to wear, Helen didn’t flinch.

“Well, Joe, it’s just that I think if a girl is going to be involved in a matinee relationship, she should do it in style, that’s all.”

A rare behind-the-scenes glimpse at all the hard work (and makeup) that went into being the public Helen Gurley Brown. (Copyright © Ann Zane Shanks.)

“You know, I expect that you’re soon going to have a book on murder! You’re going to say, ‘Now, If you’re going to murder someone—which I don’t recommend, but if you do murder somebody—pick somebody who really deserves it!’” Pyne fumed.

“Oh, Joe Pyne,” Helen purred, “you really can’t equate murder with girls having affairs. I think you have a kind of puritanical, funny, rigid attitude about things.”

As 1964 came to an end, so did Helen’s twenty-eight-city promotional tour for Sex and the Office. One day she climbed into a white, two-door Volkswagen Beetle with no air-conditioning that would be her chariot around Southern California. Her driver was Skip Ferderber, a twenty-three-year-old press agent who worked for an independent publicity company hired by Bernard Geis Associates to promote Sex and the Office in Los Angeles, and whose mission was to bring Helen to as many TV and radio interviews as possible in seventy-two hours.

There was another passenger in the car, too. Sitting in the backseat of the White Angel, as Helen dubbed her ride, was a diminutive young novelist who was quietly scribbling notes about Helen Gurley Brown for a profile of her in an upcoming issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Finishing up the final stretch of a thirteen-week promotional tour of England and the United States, Helen was hanging on, but just barely. In Los Angeles, Joan Didion found “a very tired woman indeed, a woman weary of flirting with disc jockeys, tired of parrying insults and charming interviewers and fighting for a five-minute spot here and a guest appearance there.”

Didion kept herself in the background; she was inscrutable even then. Still, she was clearly charmed by Helen’s gumption and impressed by her work ethic—if somewhat disparaging of her actual work. At the time of the interview, Helen had sold nearly two and a half million copies of her two books, combined, and Didion attributed the sales partly to various daytime and late-night radio talk shows, like Long John Nebel, that featured Helen as a guest and reached “a twilight world of the lonely, the subliterate, the culturally deprived.”

She also noted that a good number of the night owls who called in to shows to sound off on Helen Gurley Brown’s depravity hadn’t actually read her books, which were actually quite sweet and sincere. In fact, those listeners weren’t responding to her books at all, but rather to the idea of them; just as they were responding to the idea of her, a woman whose studied, seductive voice had been transmitted via hundreds of radio and TV shows over the past year, and, with any luck, would soon be on hundreds more.

But then a funny thing happened. After being shuttled around to countless tapings in Los Angeles, Helen suddenly had a hard time booking TV and radio interviews back home in New York. In November, Letty and a colleague wrote a memo to the Browns warning them that they were getting “over exposure signals on HGB.” Bookers at some of the biggest shows like The Tonight Show simply felt that Helen had been on too many times. Their audiences just weren’t interested in her at the moment, Letty reported: “No amount of idea suggesting, controversy proposals, or cajoling can change their minds it seems.”

Letty suggested putting Helen under wraps for a while, but Helen and David had another idea—they always had another idea. This was hardly the first time they had run into rejection. After Sex and the Single Girl first hit shelves, they churned out countless proposals for TV shows, some of which they pitched through the talent agent Lucy Kroll.

Among their ideas that never made it to screen: a food-themed quiz show (sample challenge: taste five types of milk, from skim to evaporated, and identify each); a game show in which ordinary people would present their ideas for new inventions in front of an audience (nearly forty-five years later, ABC’s Shark Tank would be based on a similar premise); and a cheeky talk show, Frankly Female, which Helen would host. Though aimed primarily at women, the show would also feature a male cohost to attract some men. In one proposed segment titled “EXPLAIN PLEASE!” the idea was that Helen would ask an expert a ridiculously basic question about a subject that the Browns deemed long had eluded women—such as the names of the seven continents—only they were too ashamed to admit it. A man from the Internal Revenue Service could break down a tax form to Helen on the air, for instance. Other experts could explain how to count using Roman numerals, or why World War I started in the first place. In answering, the expert would speak very simply as if to a child, using props if necessary. Easy enough for “how to change a tire,” though “How it started with the Jews and the Arabs and who’s right?” could prove more challenging.

The Browns never did convince a network to green-light Frankly Female. Nor did they have success with a comedy-drama series, Sandra (The Single Girl), about the adventures of a somewhat plain, but charming, single girl who works as a copywriter in an advertising agency. ABC rejected the idea for what were then obvious reasons. No one wanted to watch a TV show set in the world of Mad Men—especially not one that focused on a woman. “It is a series built around a female lead, and the unfortunate history of television indicates that this has been uniformly unsuccessful,” wrote the network’s bearer of bad news. (In 1966, Marlo Thomas would star as a struggling actress trying to make it in New York City in ABC’s That Girl, one of the first sitcoms to focus on a single, working woman who didn’t live with her parents. The Browns had been a bit too ahead of the curve.)

Sooner or later, something had to stick, but it sure as hell wasn’t going to be The Unwind Up, a show that promised to feature a psychotherapist named Charles Edward Cooke, coauthor of the 1956 guide Hypnotism Handbook with sci-fi writer A. E. Van Vogt. Cooke would actually hypnotize viewers into a near-sleep state—with the help of soothing music and somnolent readings of telephone directories, Teamsters union bylaws, and The Communist Manifesto. Keeping the viewer in a hypnotic state, Helen pointed out, would be ideal for sponsors wanting to soft-sell their products. Not so ideal for the viewer, perhaps. “The only possible harm that could come to anyone from this kind of hypnosis,” Helen noted, “is that they might have left something on the stove before they fell asleep, failed to put out a cigarette, or left a child unattended.”

Although most of their ideas never panned out, the Browns didn’t stay discouraged for long. If anything, they saw rejection as a kind of creative fuel—a reason to keep trying. David had lost his job enough times to know the importance of having something “in the mail,” whether it was a book proposal or a new concept for a column. Whatever it was, he always had some idea floating around—something that might lead to the Next Big Thing. All it took was one great idea landing in the right hands at the right time.

As it happened, by the fall of 1964, there was something in the mail that was beginning to spark some interest.