1965

“What was so marvelous about Helen is that she was entirely self-created. She invented herself, and then spread the message. What I love about those early years is that she never published anything she didn’t believe in. She was like Billy Graham. This was her religion.”

—Lyn Tornabene

The week the July issue was scheduled to hit stands, an affable reporter named Dick Schaap sat across from Helen and asked what she made of the fact that some people still resented her sudden ascent to editor of Cosmopolitan, considering her lack of experience.

“You don’t just fall into a job like this,” Helen said silkily, explaining how she worked her tail off at the ad agency during the week, while writing Sex and the Single Girl on weekends. “It was a best seller. It may not be literature, but it certainly didn’t bore anybody to death. I got into scoring position so I could get into the magazine. I possibly will fall on my face and the minute I do they will have a new editor.”

Schaap scribbled down her response. A reporter for the New York Herald Tribune, he was more accustomed to profiling athletes—five years before, he interviewed a young Cassius Clay before Clay became the heavyweight champion of the world. Helen Gurley Brown wasn’t typical as an interview subject, and not just because Schaap frequently covered sports. She was different even among her kind.

In between glances at the July cover girl, a juicy-looking blonde in a low-cut Jax dress, the sportswriter studied the new editor. She wore a light blue suit by Marquise and white mesh stockings. A demure black bow was affixed to her hair. As Schaap asked about her plans for the new Cosmopolitan, Helen lounged on her sofa, occasionally stretching her arms like a cat rousing from a nap. “She did not look like most editors I have seen,” Schaap later observed. “She did not act like most editors I have seen.”

That Helen Gurley Brown was not like any other editor—any other boss, really—seemed to be the consensus among the staffers and freelancers who found themselves in her office, but they still didn’t know what to make of her. “I always thought I was smarter than she was,” says Liz Smith, “but I found out later she was smarter than I was.”

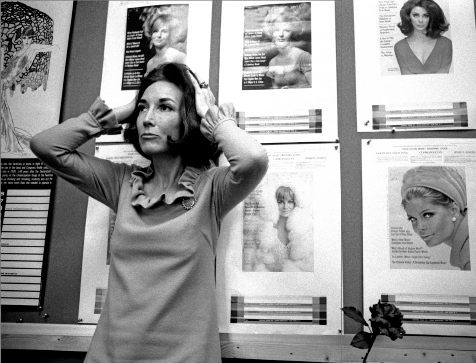

Helen during her first year as editor, 1965. (Copyright © I. C. Rapoport.)

Despite Cosmopolitan’s abysmal circulation figures in recent months, editors still took pride in the magazine’s rich history as a forum for intellectual thought—“the magazine for people who can read,” as David Brown once nicknamed it. Suddenly Helen seemed to be editing the magazine for people who were reading-impaired. She wanted articles to be “baby simple” with no unnecessary big words. “We don’t want very many cosmic pieces—about space, war on poverty, civil rights, etc., etc., but will leave those to more serious general magazines,” Helen told The Writer. She wanted fun pieces, nothing too heavy. Most important, she wanted her girls to feel happier after reading an issue of Cosmopolitan. Articles needed to be optimistic and upbeat. That meant no bad reviews of books, records, and movies, but especially movies. (She was married to a movie producer, after all.)

Helen’s rules drove Liz Smith crazy. Whatever chance she once had to become a respected movie critic, Helen sabotaged: What use was a critic who couldn’t write an unkind word? “You are censoring me!” Liz yelled. Helen dealt with Liz the way she had learned to deal with men: She listened to her, fussed over her, petted her ego, and eventually cajoled her into doing things her way. As for a certain young movie critic whom Liz had been mentoring, he clashed with Helen even more.

A few months earlier, Liz found in her mail an unsolicited review of Lilith, starring Warren Beatty, Jean Seberg, and Peter Fonda. The writer of the review was a dark-haired, long-lashed, and dimpled twentysomething named Rex Reed. Having come to New York after college at Louisiana State University, Rex was working as a press agent at a public relations office when he really wanted to spend his time watching movies. He hadn’t expected much to come of his submission to the entertainment editor at Cosmopolitan, but Liz was impressed. As it happened, he had been born in Fort Worth, her hometown, and she liked the idea of having another southerner around.

A few days later, Liz called Rex to say that Cosmopolitan’s editor-in-chief, Robert Atherton, wanted to meet with him. Not only did Atherton want to publish his review of Lilith for a nice sum of fifty dollars—his first byline in a national magazine—he wanted Rex to be Cosmopolitan’s new movie critic. Rex was ecstatic.

And then Atherton was out, and Helen Gurley Brown was in. Even if Helen hadn’t been familiarizing herself with old issues of Cosmopolitan all along, she certainly would have read Reed’s negative review of The Yellow Rolls-Royce, starring Rex Harrison and Jeanne Moreau, in the June issue. “Car lovers will drool over The Yellow Rolls-Royce. Movie buffs, however, may appraise it as a motorless vehicle for some 24-karat stars who find themselves hijacked in chromium-plated material,” he had written.

When Helen called Rex in for a meeting, he found the new editor-in-chief sitting on top of her desk wearing a skirt so short it showed off the tops of her thighs, netted in Bonnie Doon stockings. He wasn’t sure how old she was, but too old to be dressing like that—and those fake eyelashes and that false hair! Was she wearing a wig? It was only noon! He was interrupting her lunch, in fact—he noticed a little container of yogurt next to a perfectly sculpted salmon-colored rose.

“My dear,” Helen said after they exchanged hellos, “you write pippy-poo copy. I’m afraid I can’t use you because you’re upsetting my girls.”

What? Rex had no idea what “pippy-poo” meant. And which girls was she talking about, exactly? He didn’t know about the legions of young women from the middle of the country who wrote to Helen looking for advice on what to wear on a first date or on a first job interview. He didn’t worry himself over their menstrual cramps and acne scars, their broken hearts and battered egos—but Helen did, and she felt that Rex’s opinions were too critical for the new, upbeat, optimistic Cosmopolitan.

“My girls have never heard of Mike Nichols,” she explained. “They don’t want opinion. They just want to know a good movie to go to on a Saturday night at the drive-in.”

“How do you know such a girl exists?” Rex asked.