Altar and Sacrifice

NOGALES AND ALTAR, SONORA

IT TOOK SPECIAL DISPENSATION FROM RISK MANAGEMENT AT Duke to get us there, but the students had argued successfully that their experience wouldn’t be complete without witnessing the staging ground for immigrants readying to cross the desert into the United States. We were on our way with Ceci at the wheel. We drove southward from Nogales toward Altar on SON 43, where our learning experience continued en route.

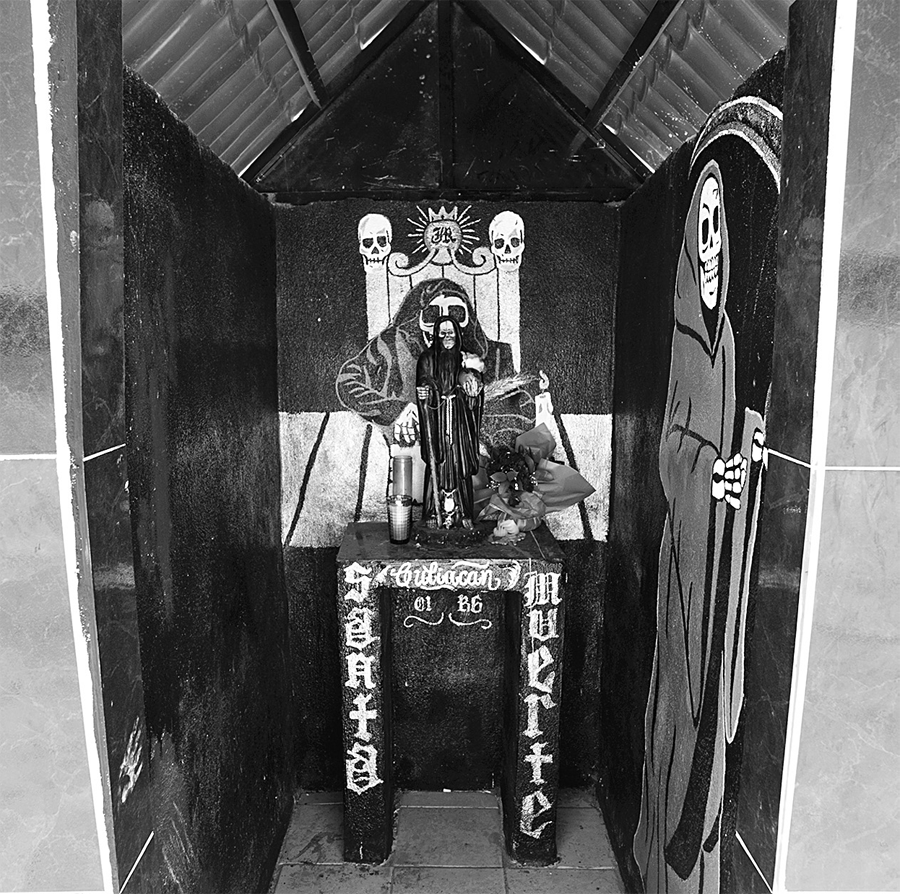

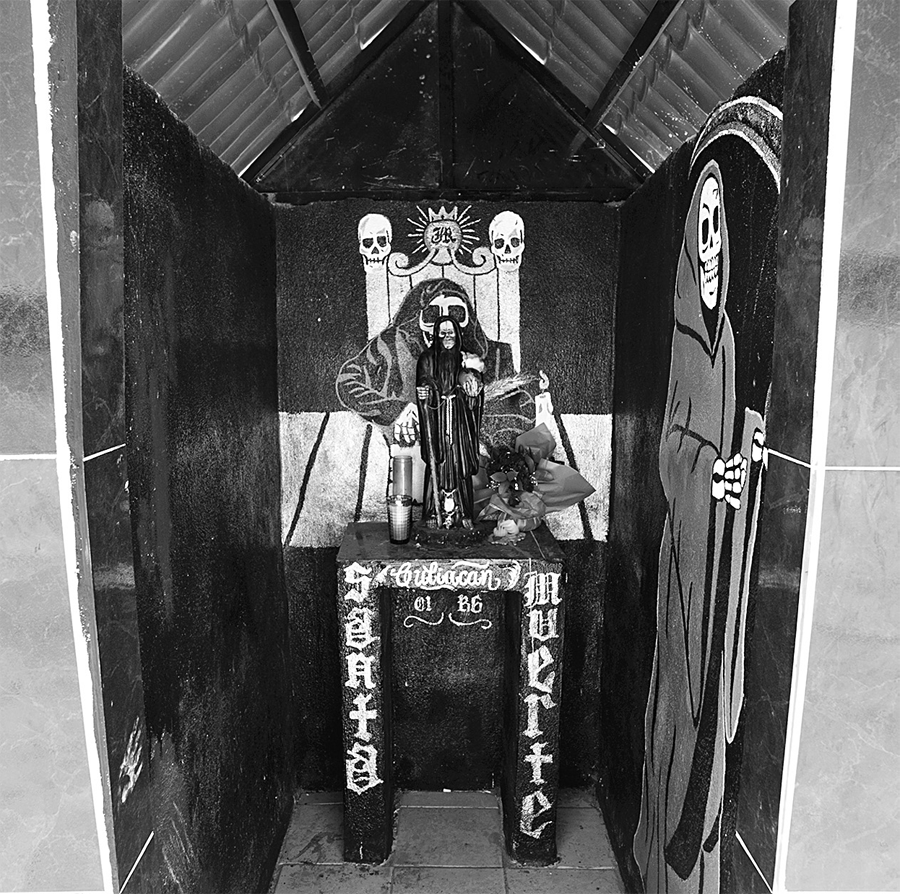

Just south of the city of Nogales, we came upon a row of a dozen shrines to Santísima Muerte (Most Holy Death) erected alongside the road. I asked Ceci if we could stop. She said she thought we would be safe enough, but she didn’t want to get out because she had no use for the “saint of darkness.” She pulled over and I clambered out to get some quick photographs, feeling some trepidation mixed with a healthy dose of curiosity. Seven of the students followed, all with their cameras drawn.

No two shrines were anything alike. I started at the top of the rise and began working my way downhill, looking into each and photographing its contents. Each had some form of a human skeleton inside representing the saint. Some held three-dimensional skeletal icons dressed in queenly finery and seated in ornate chairs. Others had only a painting of her surrounded by a variety of candles, artificial flowers, and other decorations. I’d visited many sepulchers in Latin America, including many examples of the bloody figures of Jesus, Stephen, and other martyred saints, but they had not prepared me for the ominous feel of the shrines to death herself. Something seemed unsettled, and I felt the need to look around to see who was watching and felt especially protective of the students.

One of many shrines to Santa Muerte built south of Nogales, Sonora, on the road to Altar.

According to some, La Muerte is the Virgin Mary’s skeleton. Others say she is the Aztec goddess of the underworld syncretized into a Catholic saint. But what really made me uneasy was the description Ceci gave just as I had jumped out of the van: “The narcotraficantes put those up to ask La Muerte to help them in their drug trade.” The last thing I wanted to do was to have to explain to one of the shrines’ owners why we were out there taking pictures. We passed along the whole line of shrines quickly, and then I hustled everyone back into the van and we were on our way again. “It’s good to know about such things. It’s part of our education,” I said to the students, trying to shake off my uneasiness.

But it was the town of Altar that had scared me most—especially in its heyday, when thousands of migrants passed through the town every day on their way to the Sasabe desert crossing sixty miles to the north. Altar is the staging ground. From there, vans take the migrants to the beginning point from the Mexico part of their trek on foot to El Norte, some five miles from Altar. If they survive the trip, they end up near Sasabe, the same border crossing where the Derechos Humanos Migrant Walk began.

With temperatures sometimes exceeding 130 degrees Fahrenheit in June, this was no easy terrain to walk even for a day, but I’d witnessed the town center filled in summer with men and women readying themselves for the journey north. In the winter months it was even more packed. Now the numbers had started dwindling, but the infrastructure I’d seen on previous visits was still in place.

We saw coyote vans parked alongside the church square waiting to take migrants through a restricted finca (plantation) entrance on the Sasabe road. The Migrant Prayer for those heading north through the desert was still hanging at the church altar. There were flophouses where dozens of migrants waited as they searched for the right coyote to guide them. And there were stores like Super Plaza that specialized in black clothing for hiding from helicopters. There were black backpacks, shoes and socks, lightweight foods, and water jugs for sale. The whole town had organized itself around the business of receiving and sending migrants from all over Mexico and Central America. Even the local baseball team was named the Coyotes. The church had started up a ministry just for the migrants.

But by 2010 the massive river of migrants had dwindled to a trickle. Part of the reason was the slowdown in the U.S. economy. Militarization of the border also contributed. But the most ominous part of this operation was that our border crackdown had led to increasingly sophisticated means of crossing, which then gave rise to a mafia-like infrastructure for human trafficking. The worst of the coyotes had ramped up their trade in people. A process that had at one time been individualized had now become more controlled, and criminals had gotten hold of the means to get people across the line. The prohibition of migration had led to more profitable trafficking and the drug cartels had entered the business. Now it was more dangerous than ever to be a migrant in public. Kidnapping and rape had become more prevalent.

Many migrants are no longer able to choose Altar as an option and must sell themselves into the world of the traffickers, often as drug mules. Payments of human flesh might mean safe arrival. Passing through Altar had been the old way by which migrants made their way to the church square. Their prayer to the Virgin came first. Afterward they would find a guide who would take the money for the van. Though it was dangerous as hell, the individual migrant still retained a small amount of agency.

But now those who had erected the shrines to Santisima Muerte were in charge. They don’t stop at a church before setting out. Their routes are secret, their destinations less certain and controlled by hidden forces. Delegations like ours would never see them.

But even with the drastic reduction in numbers, the students and I were able to meet and speak with a few migrants. We had been asked by church members to pass out flyers about the migrant hospitality house called CCAMYN (Centro Comunitario de Atención al Migrante y Necesitado). I walked up and introduced myself to two young men named Efrain and Lorenzo and told them there was free food and housing a few blocks away. They thanked me, but said they were waiting on a coyote to line them up with a van so that they could leave that morning. They already had their backpacks full of food and water, their cheap flat-bottomed tennis shoes were in fairly good shape, and they had on hats, loose shirts, and long pants. They had been through the desert before and felt fairly comfortable with the trip, they said. Still, I could see fear in their eyes.

I couldn’t imagine situations in which human beings would be more vulnerable than these two were at that point. The traffickers, the sun, bandits, double-crossers, poisonous snakes, bad water, and La Migra—the U.S. authorities—all awaited them. Of course they really couldn’t trust me either, but I posed no real threat standing there in front of the church. When asked about jobs, some migrants answer, “Whatever I can get.” But when I asked these two, they knew their destination exactly. They were heading back to the northern California strawberry fields where they had worked before. They knew they would have to travel at least a thousand more miles from Altar, going through Sonoran desert on both sides of the border and nearly the entire length of California, to end up on a farm they already had worked on.

I asked Efrain and Lorenzo if I might take their photograph, and they nodded and looked directly into the camera. Their resolve said they were going no matter what, but I thought I could see in their eyes that they didn’t want to do this. I knew this wasn’t a choice; it was a sacrifice. I gave them the common blessing said to travelers in Spanish, “Vayan con Dios.” They looked down at the ground and said gracias.

Every year of the Altar migration phenomenon, the congregation of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe del Altar, the church in the center of town and the sponsor of CCAMYN, makes a pilgrimage from their sanctuary to the beginning of the migrant trail where the vans pay their entry fee to the landowner. The pilgrims pray together inside the church, read aloud the Migrant Prayer posted on the wall, and then walk toward the entrance to the Sasabe road, some five miles away. At their destination they had planted three twenty-foot-high white crosses with black lettering. One cross read “Familias Migrantes,” another said “Mujeres,” and the third, “Niños.” When the walkers arrive at the crosses, they light candles and pray for all migrants who pass there.

The words “La Familia” and “Mujeres Migrantes” are inscribed on two crosses erected by the Catholic church in Altar at the beginning of the often-used migrant route through the desert.

I made that pilgrimage along with seven students on our first delegation of the DukeEngage program. We walked with the Mexican townspeople following behind Padre Prisciliano Peraza, a stocky man dressed in a white robe, a wide-brimmed cowboy hat, and boots. We arrived at the tall white crosses and began to encircle the father. He had already started praying when several vans pulled up at the guardhouse not more than a hundred feet away from our group.

With my head bowed, I looked out of the corner of my eye at the attendants emerging from the little wooden house as they approached the vehicles. I saw them ask each migrant to pay a fee of fifty dollars U.S. per person just to pass through. The migrants were essentially paying an entrance fee into the most dangerous corridor on the border, the corridor that had taken the lives of many people like them. Then, with cash exchanged, the attendant opened the gate and the vans sped northward, leaving a cloud of dust wafting toward us.

In silence, one by one, each of us lit our votive candles and stood them upright in the sand under the crosses. They burned next to spent ones that had fallen over. At the end of our service, people gathered the used glass canisters from previous pilgrimages. The red wax had melted and spilled from each of the old glasses and hardened in the sand beneath. It looked like blood.