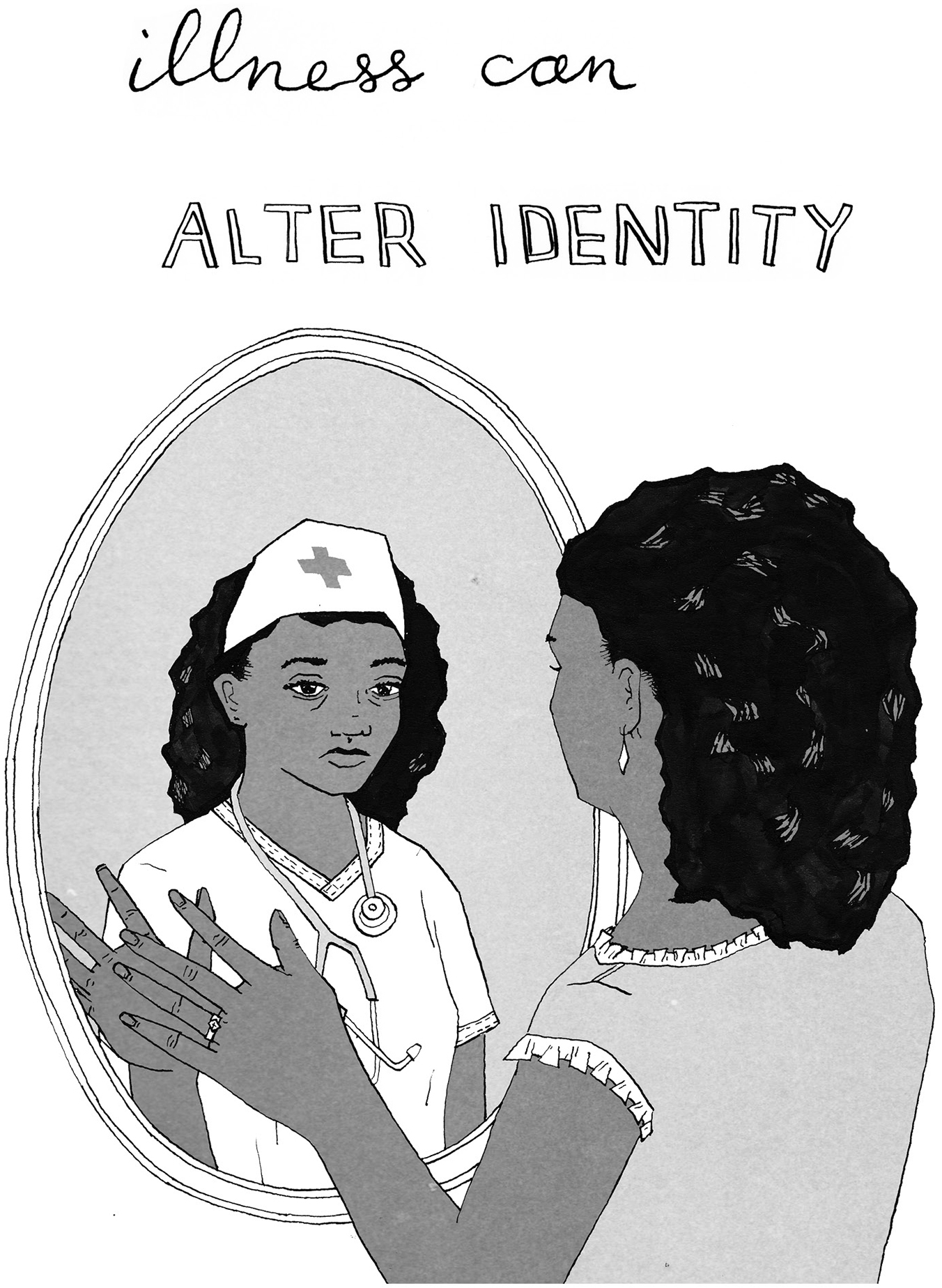

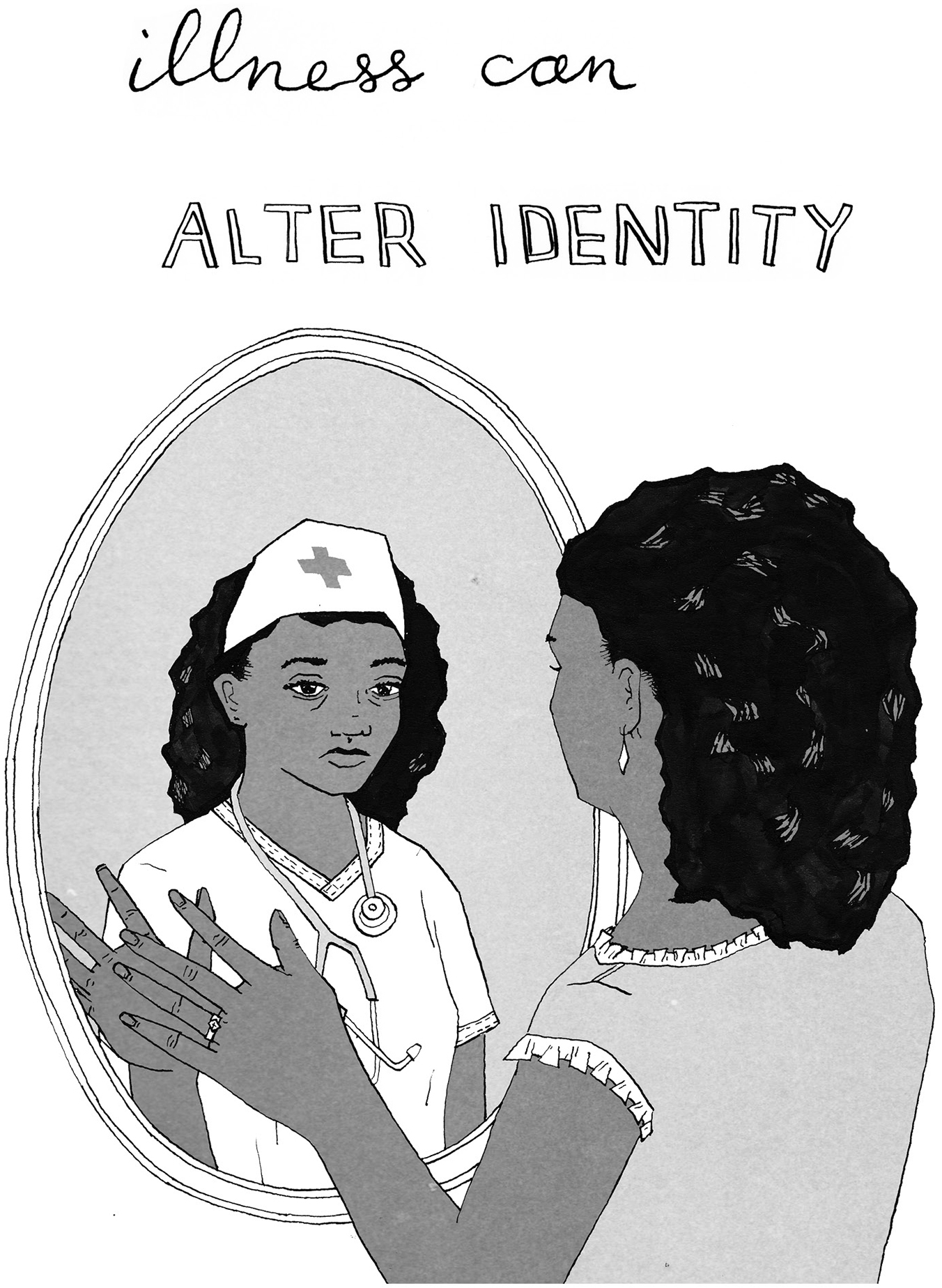

You may be playing many roles now: daughter, nurse, therapist. The shapeshifting is temporary, but that doesn’t make it less difficult.

Illness changes, or at least challenges, everything: certainly our relationships to ourselves and to others. The psychotherapist and palliative care chaplain Reverend Denah Joseph has spent years observing and guiding couples through this phase of life. As she says, “Illness is about the relationship. In my practice this is usually the bull’s-eye, the tender core where illness is experienced most acutely as both strengthening and undermining our bonds—the most important source of safety, connection, and attachment that any of us has.”

Some relationships will grow and thrive under these conditions, and some won’t. This chapter focuses primarily on romantic relationships, but be aware that all of your relationships will change, subtly or dramatically, and that everyone in your orbit is affected. Roles bounce around: husband becomes nurse, wife becomes aide, and so on. And all this shifting upsets the balance of your emotional ecosystem.

You don’t have to forgo your familiar role entirely. Facing the end can be an incredibly tender time between people. Partners can forgive and be forgiven. Patients can teach caregivers how to be vulnerable or raw. And everyone can show the people they love how much they love them.

——

IT’S A SHOCK TO THE system when you can no longer do the things your partner depended on you to do—play catch with the kid, take out the trash, not wet the bed. All of the things you took for granted, even the smallest ones, might be stripped away.

Make no mistake, transitioning from the role of spouse or partner to patient or caregiver is a hard one, whatever your age. When you’ve lived your entire life under a certain identity—patriarch, matriarch, child, boss, you name it—it may feel next to impossible to assume a new one. The semblance of independence gives way, and that can overwhelm your long-established dynamic and the patterns of your care for each other, and for yourselves.

Acknowledging what’s gone in your relationship—missing it, mourning it, whether through words or action or ritual—is powerful, and it’s key to living on. This is how you can protect intimacy. Give each other permission to vent and wade through the emotions that come up, even if they’re hard or unpleasant. Doing so is a way to offer real support to each other. Being authentic will protect you both from feeling like too much of yourselves is going away. There will be more to go.

Here are a few ideas for sticking together as you go through this. These are for both of you to consider:

• Rally around things that have little to do with your illness.

Insist that you are partners (or a family) more than you are “patient” and “caregiver.” Maybe you devote Wednesday night to doing something you have always enjoyed together, such as a game of cards or listening to music.

• Reflect on what brought you together in the first place.

We forget. Remembering the charms you first fell for in each other; the old jokes between you; the routines, places, food, books, or whatever drew you together might still do that now. I’m reminded again and again in clinic how much trouble befalls people when they lose touch with the basics of their lives, most importantly with what brings them joy. If those things just aren’t accessible now, the act of remembering together can be powerful by itself.

You may be playing many roles now: daughter, nurse, therapist. The shapeshifting is temporary, but that doesn’t make it less difficult.

• Make new rituals and routines. What’s something new you can do together? Movie night? Reading aloud to each other? Stopping at a park or an ice cream shop after doctor appointments? Maybe a sip of sherry at medication time? One kiss per pill. Prizes for pooping. Make it up. The point is to settle into this new, weird reality together and make it yours.

• Make sure you both have time to yourself. Do things independently of each other. This might mean time spent alone or with different people; in silence; with a book; out for a meal. Your relationships with yourself and the wider world are also important.

• Appreciate each other. One gnarly thing about being weighed down with symptoms and treatments is that it’s easier to miss the subtle sweetnesses happening around you and for you. Slow down and notice. Look each other in the eyes. Hold that hug a little longer. These moments settle the nervous system. Try looking for things to learn about yourselves and each other—moments of exchange—and maybe each of you will see how strong you are, living this experience of frailty. You can’t choose so much of what you’re facing, but you can keep choosing each other, hour by hour.

——

YES, COUPLES DO BREAK UP at the end of life. A terminal diagnosis may bring some people closer together, but it’s not likely to fix a relationship that’s already in trouble. A breakup—hard under the best of circumstances—can be devastating when you’re sick and feeling all the more vulnerable. On the other hand, it can feel cathartic and empowering and smart to let go of a relationship (or anything) that’s not working and is consequently sucking up precious air.

——

IF YOU FIND YOURSELF WANTING to leave or in the middle of a breakup, quickly look for other emotional and logistical avenues of support. Was your partner driving you to your appointments? Who else in your circle can do that?

In addition to telling close friends, it’s a good idea to let your clinical team know if you’re newly single. They need to understand what’s going on with you and may be able to help. And ask your doctor or insurer directly for a recommendation for a social worker. Whether you’re seeking counsel on obtaining medical insurance, need help with rides or meals, or could use a friendly conversation, a social worker can unearth whatever resources exist and help you access them.

——

ARE YOU RELYING ON YOUR spouse’s medical insurance? before one woman split with her partner, she asked him if she could remain on his insurance plan for a limited time. He still cared for her, and it was an amicable split, so he said yes, and they remained connected in that way until she was able to secure her own plan a year later. People strike deals in this way all the time. But when a tidy way forward is not at hand, it’s a good idea to reach out to a social worker or case manager. A change in your marital status might mean, for example, that you lose significant income to pay for doctor’s visits, treatment, and in-home help. But then again, you might now qualify for programs, such as Medicaid, that were not available to you on a joint income.

——

THE THOUGHT OF LEAVING YOUR loved ones behind is hard to bear. You may be angry at the universe and everything in it. You may be exhausted or in pain. But is it okay to be crabby? To fight? To tell your partner to get lost when he or she is being insufferable?

The answer is yes. Of course it is. This phase of life is just that—life—and everything human remains. One way to lose each other is to put on kid gloves. Don’t deprive each other of the full range of emotion; illness diminishes enough. So, yes, when it comes to expressing yourself, this time should be no different from the rest of life.

If you were a couple that fought before a life-changing diagnosis, that behavior isn’t likely to change, and may actually bring a feeling of normalcy—for some couples, arguing is a form of intimacy. Of course, if it starts to happen all the time or turns into cruelty, it can do real damage, pushing away those you need most.

Remember: Behind most complaints is a request. So, what do you really want? Do you want to be alone? Do you need to be told you’re still attractive? Are you blowing your stack with your partner because you feel safe with them and not with anyone else? What a great thing to let the other person know.

——

DURESS CAN BRING OUT THE worst and best in us. I’ve known many couples over the years who swore that illness saved their relationship, usually because it sanded down the jagged edges that had been developing between them or gave them an excuse to finally communicate and dare to need each other.

For Jen Panasik, a 40-something mom with two young kids whose husband had stomach cancer, taking care of her husband brought a renewed closeness and sense of purpose. In fact, the years during which her husband’s cancer was in remission ended up being the hardest. “It was actually the worst time for our relationship,” Jen says. “He was starting to drink a lot . . . because he was petrified of it coming back. That’s how he was dealing with it, instead of talking to me.” His behavior enraged her. “I told him, ‘Hell no, you’re cancer-free, you can’t check out, I’m sorry!’ I know it’s him hurting and he’s in pain, but I kept thinking You should be getting healthy! That’s what you should be trying to do, right?”

The cancer returned after three and a half years, and they were devastated. But the recklessness stopped almost immediately. “In a way, it’s easier when we’re dealing with the illness, because we feel like we’re doing something together.”

There is some caution to note here, too. The ups and downs of life with illness will yank your relationship around. The struggle itself—the drama—has its own pull and can become desirable in a strange way, or at least anticipated, leaving you either listless or anxious when it’s absent. So stock up whenever possible, on energy or rest or joy. This will help you keep up when things are chaotic, but also to unwind when they are easier. Give your nerves a moment to reset.

——

IT’S HARD FOR A COUPLE to stay in step with each other. What one person needs in the moment may derail the needs of the other. But at any given time, what this all comes down to is safety—both emotional and psychological. With the ground shifting beneath you and your body falling apart, that can be hard to achieve. But we need it, all of us, no matter how tough we are. When we don’t feel safe, we constrict, run, build walls, or put up our dukes.

Losing your independence is very, very difficult, especially if you pride yourself on self-reliance. Needing more and more help can be demoralizing to the point of despair. It’s nearly impossible for a partner to grasp how lonely dying makes a person feel, no matter how loved she might be. Indeed, each role—patient and caregiver—comes with discrete difficulties that are impossible for the other to fully grasp. Try to give each other the respect that situation deserves.

The goal is to feel that you are seen. That you are okay as you are. This state of mind is created and nurtured by the two of you, so the advice here is for patient and caregiver alike: Get basic. Listen without judgment. Drop your defensive armor. Vent. Spare the ultimatums, and focus on the thing between you that you are both in charge of creating: the relationship.

——

A state or event resembling or prefiguring death; a weakening or loss of consciousness, specifically in sleep or during an orgasm.

—Oxford English Dictionary

WHEN YOU’RE SICK, ONE OF the first things that may get neglected is your physical relationship. It may feel extravagant or even dangerous to afford your body any pleasure, but let’s check those assumptions. Dr. Marianne Matzo, a nurse practitioner and researcher who studies sexuality at the end of life, recounted the story of a longtime cancer patient who died while his wife was giving him oral sex. In the hospital, no less. To be clear: her husband died from advanced cancer, not a sex act. The point is that this couple kept active until the very end.

——

CLINICIANS AREN’T ALWAYS GREAT ABOUT talking through how sex may change when you’re sick. And those changes range from the physical to the emotional: fatigue, grumpiness, a real headache, lack of interest, embarrassment, pain, vaginal dryness, erectile dysfunction.

—

TIP

If you are hoping to be a parent, ask your doctor about all side effects before starting any new treatments, as they may affect your reproductive organs.

Men, you are likely to hear from your doctor about whether or not you’ll be able to have an erection after treatment, at least from a plumbing point of view. Because erectile dysfunction is so common, and because there are pills nowadays to help, it’s become a fairly standard, if incomplete, conversation. That’s good, but blood flow is only one issue of many; ask sex therapists, and they’ll tell you that sex is far more a psychological matter than a physical act.

When it comes to talking to women about what sex will be like after treatment, things aren’t quite so clear. “For a woman with cervical cancer, the oncologist usually recommends radiation and surgery—but [they’re] not going to mention to you that there will be problems,” says Matzo. “So then, down the road, when she’s ready to have sex, she finds out, saying ‘Holy hell, that hurts, what happened?’ ”

If there’s any question about your ability to have safe sex, start with your doctor or nurse. They can be very helpful, especially when it comes to the mechanics. Here are some opening lines to break the ice:

• Start the conversation with: “I’d like to talk to you about something that’s a little personal.”

• If you’re in a room with a crowd: “I have something private to discuss, can we talk alone?”

• If you aren’t sure whether you will be able to have sex (or be interested in it): “Will this treatment/procedure change my ability to have sex?” And “Is there a way to preserve or improve my sexual function?”

• If you’re worried about safety: This has to be delivered point-blank: “Is it safe for me to have oral/vaginal/anal sex?”

We realize that all this might be awkward, but breaking through the awkwardness is a huge step in the right direction.

——

SEX AFTER TREATMENT WILL BRING a whole new series of sensations. Your body may feel different to you; some parts numb, others extra sensitive. And that’s just the physical part. Your sense of who you are—your confidence, limits, energy—may have shifted, too. So a frank conversation with a doctor or nurse is a good place to start.

As Susan Gubar wrote in the New York Times, “At diagnosis, quite a few cancer patients spy Eros rushing out the door. . . . It can be difficult to experience desire if you don’t love but fear your body or if you cannot recognize it as your own. Surgical scars, lost body parts and hair, chemically induced fatigue, radiological burns, nausea, hormone-blocking medications, numbness from neuropathies, weight gain or loss, and anxiety hardly function as aphrodisiacs.” Illness, however, does provide a great excuse for revisiting our bodies and for paying attention anew.

——

FOR CHARLIE, A YOUNG MAN with cerebellar glioblastoma multiforme, a rare form of brain cancer, and his girlfriend, Amanda, intercourse was quickly off the table. “I know he feels bad about not giving me that. But when we tried to have sex a few months ago, he was mid pump and just crumpled on top of me and said, ‘I can’t do this.’ He’s exhausted or nauseated most of the time from the treatments he’s undergoing—not exactly conditions that put you in the mood.” But intimacy comes in many forms. For them, cuddling took the place of sex.

Another of Marianne Matzo’s patients, a man who could no longer have an erection, voiced concern that his wife would leave him. Matzo turned to the wife and asked, “What do you think about no longer having sex?” His wife confessed that she was actually relieved to hear it. She didn’t need it. “We still cuddle, and we’re still close,” she said. Sometimes all it takes is talking it through—with or without the help of a therapist—to realize that you are still able to be romantically connected with each other in a new way.

The upshot? Screw sex! It gets a lot of attention, and yes, it can be very hard to let it go for good, but intercourse has never been for everybody. And there are all sorts of variations on intimacy waiting to be explored. Let that be exciting if you can—maybe the nervousness can harken back to a time when you were less familiar with one another. There is a lot of body beyond the groin, and any part of it can become erogenous. Find a patch that doesn’t hurt—an elbow, toes, hair, wherever—start with a light touch, and work from there. Communicate faithfully and plainly so you know what’s working and what’s not. Be patient. Here are a few tips:

• Make small gestures. A touch on the shoulder, a hug, a foot rub, holding hands. Anything that feels good in the moment.

• Don’t fear the hospital bed. Medical interventions and equipment might put physical barriers between you that suggest you shouldn’t be touching. Tubes, needles, hospital beds with buttons for everything—don’t let them get in your way. A hospital bed need not be a prison. It’s perfectly legal to crawl in with your beloved. Those side rails are retractable.

• Ask for privacy. Wherever you are—hospital or nursing facility or hospice or home—you don’t need to justify asking others to take a hike. Just say, “We want to be alone for a while. We’ll open the door when we’re ready for people to come back in.”

• Tell each other what feels good. A place to touch or a way to touch. Maybe it’s certain language used. Or a thing to wear. Whatever helps you feel light or good or unafraid for a moment. You might think it’s obvious, but it likely isn’t, so say so, or show so. And of course, tell each other what feels bad, too.

——

I HAD A PATIENT WHO told me he’d never really been comfortable with human contact in the conventional sense. You could tell by how he was with people in the clinic, from fellow patients in the waiting room to staff at the front desk. But he wasn’t as miserable as they thought he was. For him, connection came through his camera. He loved to go for walks through the city at night and take pictures of spontaneous street scenes. He had an amazing eye for people and objects in relationship to one another, as long as he could keep a distance. His photos revealed an affection for others that few felt from him otherwise.

However you engage the world, pay attention to what moves you. Look for these lifelines wherever they show up.