CHAPTER 7: 1895–1905

The Second Railway Mania and the Russo-Japanese War

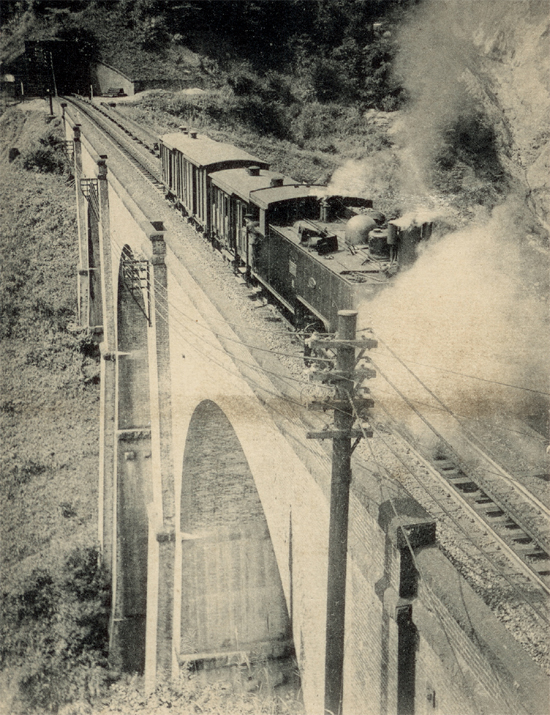

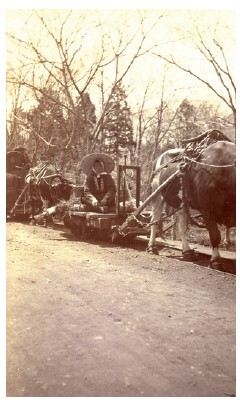

The extremely short length of this train—two “brake vans” (cabooses) and a single box car—leads one to believe it was a special train either with an important cargo or for maintenance, repair, or “break-down” purposes. The location is the viaduct near the Usui (Shin’etsu) Line summit. The prodigious amount of steam seen escaping from the front of the locomotive seems to indicate it is in need of new cylinder packing to stop leakage: perhaps an ailing unit working its way back to shops for repair.

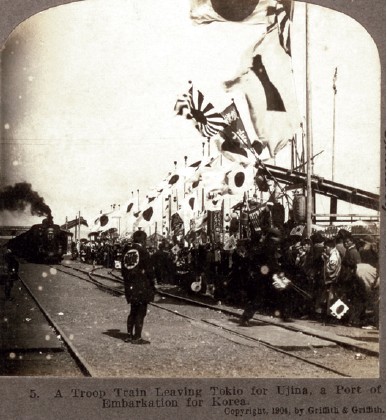

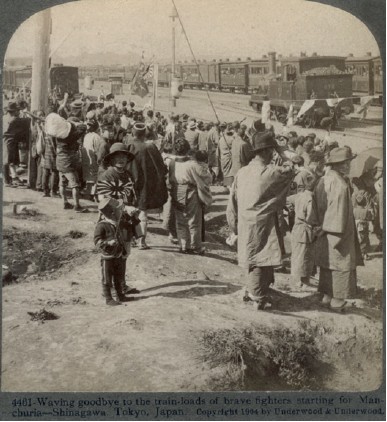

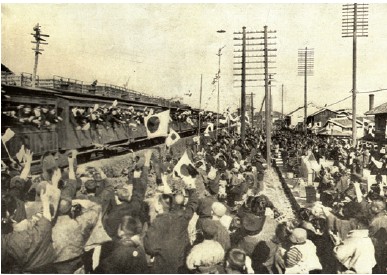

The defeat of China in the Sino-Japanese War not only boosted Japan’s self-image, but also went a considerable way towards creating the perception worldwide that Japan was henceforth a confirmed regional power with considerable potential of becoming a world power. In the aftermath of the war, a wave of energy swept the nation, and with that exuberance, Japan experienced a second railway mania. In the year after the war, according to one source, roughly 20,000 miles of competing projected railway lines were put forth by various proposed companies. Only a fraction received the approval of the Railway Council. Schemes were posited in all quarters of the realm for railway extension. The two years of 1896 and 1897 were remarkably active. 555 applications for provisional charters were received in 1896 alone. Private railways had by now become beyond question the primary builders of new railway line, the amount of private railway line increasing, on average, about 400 miles per year in both 1897 and 1898, a remarkable achievement when compared to prior years. The enthusiasm was not confined just to the home islands: railways using Japanese financial and technical backing were projected in Korea, where as a result of the war Japan’s influence was now firmly recognized, as well as Taiwan, the one significant territorial gain ceded by China to Japan. (Japan had demanded and had been ceded the strategic Liaodong peninsula and other areas, but France, Russia, and Germany had interceded, nominally on behalf of China, but coincidentally in their own self-interest, in what became known as the Triple Intervention, to force Japan to retrocede all Chinese territories gained except Taiwan and the Pescadores, which quite naturally was bitterly resented by the Japanese populace.)

In the aftermath of the war, proposals were made to nationalize the private lines, to build a direct line through central Tōkyō to connect the Shimbashi terminal with the Nippon Tetsudō’s Ueno terminal, a distance of 2½ miles, and to build a central station. Prior to this time, the German architectural firm of Ende-Boeckmann had been engaged to do city planning for Tōkyō, and the decision was made in 1895 to build such a line from Hamamatsucho station, just below Shimbashi, to the proposed site for a central station to be built in an area between the Imperial Palace and Ginza. It was suggested that the new line be constructed as an elevated line on an arched masonry viaduct, the under-side of which could be rented for warehouse (godown was the term of the day) or shop space, thereby generating income to offset the high land acquisition and construction costs, similar to a plan that had been undertaken in Berlin. An appropriation of ¥3,500,000 was passed by the newly prorogued Diet to cover costs. It was proposed that the Nippon Tetsudō should thereupon build a line south from its Ueno terminus to join at a new central station. Even at this early date, it was realized that due to the land values, the cost of construction would be sizeable. The Nippon demurred; understandably perhaps in view of the high land acquisition costs the scheme would have entailed, and for a time the scheme was to complete the line as far as the new proposed central station site, which was planned to serve as a terminus until further construction funds could be made available. In 1896, planning for the new elevated railway was entrusted to Franz Balzer, of the Royal Prussian Railways’ Stettin office, who had had a hand in the similar Berlin project.

The IJGR was called upon for the first time to participate in its first Imperial Funeral in January 1896. The Empress Dowager had died that month at Aoyama, and a special train was scheduled to conduct the Imperial coffin to Kyōto for burial alongside the Komei Emperor on February 2nd. There was accordingly something less than a month for the IJGR shops at Kōbe to turn out a suitable Imperial train for the occasion. There were at this point several Imperial carriages, based in both Tōkyō and Kyōto, but no bier carriage. With such little time at hand, work was focused on building the carriage for the Imperial coffin, while a first class and a first/second composite carriage were hastily converted to serve as new carriages for the Imperial Party. Japan’s first State Funeral train consisted of four first class carriages, one first/second composite carriage, three second class carriages, the bier carriage, two goods trucks (converted for use for baggage), and three brake vans (for railway officials). Departure was at 2:00 p.m. from Aoyama and arrival at Kyōto was the following day at 8:35 a.m. According to the Imperial Railway Department, “locomotive tenders” (freshly stocked with water and coal, leaving one to wonder if the main locomotive was changed or not) were changed at Shinjuku, Yokohama, Yamakita, Numadzu, Shizuoka, Hamamatsu, Nagoya, Ōgaki, Maibara, and Baba. Lest there be any delays or mishaps, the train was double-headed over mountainous sections of the route. The top engineers and firemen were selected for the train, and two back-up engine drivers accompanied the train in case of mishap. Special carriages were held on reserve at all the planned stops, to cover any exigencies. Clearly, the care evidenced was befitting the Imperial responsibility assumed. The day had changed from the times when an Imperial Train could be routed through an improperly set turnout at main line speed.

Curiously, on the return trip, one of the few instances was recorded when the Emperor Meiji actually asserted his Imperial will by whim. The Imperial train was set to depart Kyōto at 8:55 am, but on the morning of departure, the Emperor requested to have the train depart twenty minutes later. When informed that this would wreak havoc in the IJGR’s Tokaidō main-line schedule, he was indignant and is reported to have crossly retorted by saying, “Why should it be impossible to rearrange the schedule, considering that this is a special train for my use?” Obviously, his majesty had little inkling of what ramifications such a change would have caused on the timetable and railway operations of that particular day.

This map shows the extent of the railway network as projected on March 1897. By this point, many of the trunk lines on the Pacific coast of Honshū have been completed. Major building efforts were being concentrated on Hokkaidō, Kyūshū, Shikoku, and along the Sea of Japan coast. Many of what would become the commuter lines of Tōkyō are starting to appear.

On the heels of war’s end, a trend of marked service improvements was becoming evident among certain railways, starting with the San’yo Tetsudō’s introduction of the first station porters, the akabo (lit. “red caps”). The war had given a boost to San’yo traffic and thanks to Nakamigawa’s foresight, one of it’s English language publications could boast,

“... the entire track, with the exception of a section of six miles, is free from any sharp curves or heavy grades [both impediments to high speed running], while the road-bed throughout, because of its unusually solid construction, affords the smoothest and easiest possible running of trains.”

As the century drew to a close, the San’yo overcame its lingering land acquisition woes and began to assume the form of a major trunk line. With typical San’yo vigor it showed signs (even before it had completed its mainline) of being the innovator among railways in Japan; a reputation it would cement in the course of following years. That innovations sprang from the San’yo is understandable when one considers that it faced the stiffest competition from well-established Inland Sea steamship lines that ran services to many of the towns along the line. In the earlier mentioned brochure-guide, the railway touted its innovations:

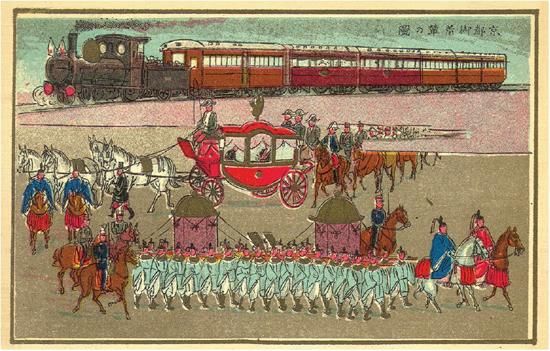

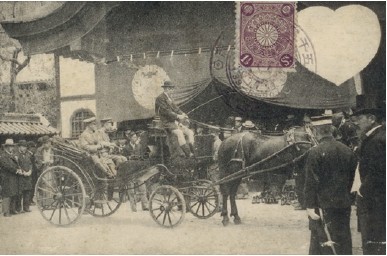

This postcard is believed to depict the funerary procession and train for the Dowager Empress Eisho. Shown in the foreground is part of the cortège in traditional court attire, followed by the Imperial Carriage, and at top the funeral train itself. The locomotive appears to resemble one of the Sharp Stewart D1 (later the 5000 Class) 0-4-2 tender locomotives that were among the first lot bought for the Kōbe–Ōsaka–Kyōtō route, although undoubtedly one of the newest and finest British or American 4-4-0s would have been used for the occasion.

“... It is now conceded that in America the art of railway management has reached a higher state of development than elsewhere.

The management of the Sanyo in the adoption of the latest modern inventions and appliances has taken America for its model, with the result that more attention to the comfort and convenience of travelers may be found on its line than on any other part of the railway system of Japan.

...

In the winter season the first and second class carriages are well-provided with heaters, while at all seasons electric lamps on the night trains have superseded the clumsy and noisy English system of car-lighting.”

The San’yo was a veritable fount of innovation. It kept its ticket offices open into the evening, bucking the archaic practice of limited sales hours then generally in place on other lines. It introduced group rate tickets, and tickets that were good for ten days rather than strictly for the day of issue. It made arrangements with the IJGR to operate a through-car service to Ōsaka and Kyōto. (For it’s part the IJGR was permitted to operate excursion trains over San’yo metals.) The San’yo instituted a half-rate return fare for round-trip tickets on longer distance bookings. It was the first to adopt the American system of through-checked baggage. At a time when no dinning cars were operating in Japan, a San’yo first class passenger could order catered meals at stations along the line that would telegraph the order, free of charge, to certain stations farther along the line with catering facilities so that a hot bento box meal (choice of Western or Japanese cuisine) would be waiting at the next catering station on the train’s arrival. Its improvements were not always focused on passenger traffic: among the innovations introduced by Nakamigawa’s proud line were the first widespread use of American-style freight cars on trucks outside Hokkaidō, and some of the first steel-bodied wagons, for coal haulage. As noted, the San’yo was one of the more enthusiastic early adopters of American-built locomotives, while the more conservative Nippon Tetsudō continued to remain loyal to British-built locomotives for some time.

1896 saw the introduction of class color coding that was to become a future nationwide standard when the seven year-old Kansai Tetsudō started coloring first class tickets white, with a corresponding white stripe along the sides of first class passenger cars, blue tickets and car stripes for second, and red for third class. By 1898, the first electric lighting had been introduced on San’yo passenger cars as noted and in the same year, the innovative San’yo had introduced “car boys,” young men who served on-board trains; what we would today call stewards or attendants.

“Car Boys” came to be an institution, and as demeaning as it sounds today to have the word Boy embroidered on the collar of one’s uniform (as the car boys of the Japanese railway service did), at that time, when the word hadn’t acquired such a pejorative connotation, it was undoubtedly taken with more of a matter-of-fact reaction. Apparently, they outshone many of their American counterparts—Pullman Porters who were grown men. One American effused, “There are [in Japan] all the modern conveniences to be found on an American train, including politeness on the part of trainmen, which goes much further than our popular notion of civility.... The nattily uniformed ‘boy,’ who is called that even by the Japanese themselves, is a sort of ideal Pullman porter, who attends to his duties as no [American] Pullman porter would think of doing, and smiles his sincere gratitude for the few coppers that a thankful passenger gives at the end of the journey.”

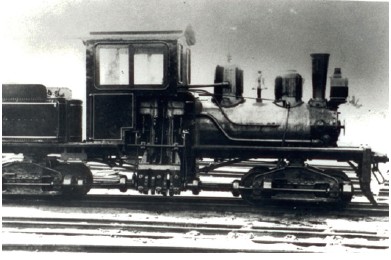

A Schenectady D12 Class (6400 in the 1909 renumbering) locomotive is seen handling an IJGR excursion train to Maiko beach via the San’yo Tetsudō mainline before the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War. The photo dates to sometime between 1902 and 1904. Among American builders, Schenectady, Brooks, and Rogers all were very active in solicitation of orders from Japan, along with their principal competitor, Baldwin. These locomotives were results of the first competitive bid process undertaken by the IJGR. The 6400 class is easily recognized by its distinctive asymmetrical cab-side window configuration.

In point of fact, another traveler found the number of youths who held jobs of not inconsiderable responsibility on Japanese railways remarkable. These were perhaps the young people of whom Surgeon Purcell was speaking in the 1870s: “... youngsters, old-fashioned before their time by reason of their need to work for their daily food from tender years...” Teenage boys occupied every post from the car stewards to the ticket collectors at the wickets (the British ticketing system was employed), to the station booking and ticketing agents, to the train guards who rode in the trains’ baggage cars and were responsible for applying train brakes and acting as safety lookouts, often chosen for having some ability in English language in order to be able to assist foreign travelers in case of need. Young girls as well were often used as what the British called crossing guards, the worker who closed the gates at roadway crossings to stop traffic on the approach of a train.

The San’yo was not alone in the introduction of innovations. On November 21, 1898 the Kansai railway, which had been inching eastward from Ōsaka, by a combination of mergers and construction of new lines, reached Nagoya, thereby creating the first alternative rail route between the two cities in competition with the IJGR’s Tokaidō line, and the first instance of significant genuine competition in Japan’s brief history of railway operations. Not oblivious to the need to project its image over that of the IJGR with which it would have to compete, the Kansai built an imposing Neo-renaissance station in Nagoya that compared very favorably to the one-story wood-frame and tile roof standardized IJGR design station,1 such that for a while, the Kansai Railway’s Aichi Station became known locally as the Gateway to Nagoya. Th at competition was in large part responsible for ensuing service improvements by the IJGR and started a process whereby the IJGR was prodded into improvements in order to meet the new competition arising from private companies. But not all private railways launched headlong into service improvements. While the San’yo was developing the reputation of being an innovator, the Nippon Tetsudō was developing a reputation for being hidebound and for treating its customers with something approaching condescension.

This view of a San’yo Tetsudō 4-4-0 shows the classic lines of a high-drivered (for Japan’s narrow gauge) 5’ 0 ¾” Baldwin express passenger engine introduced in 1897. On absorption into the IJGR roster, its class was designated the 5900 Class after nationalization. The San’yo Tetsudō had perhaps the best reputation as being one of the more innovative and best-equipped railways in Japan at that time. Note the state-of-the-art steam turbine electric generator situated between the headlamp and chimney to power the large American style headlamp, the likes of which would enable the San’yo to equip its passenger fleet with electric lighting. (Nevertheless, the marker lamp on the buffer beam is a thoroughly British oil lamp.) Just to the right of the buffer beam is a San’yo iron-plate open wagon for heavy coal traffic. Such a wagon, at a time when most Japanese railways were using wooden-bodied varieties, is another example of the San’yo’s forward-thinking philosophy.

There was a need for service improvements in many aspects of the typical Japanese passenger train of the day. With the advent of the first trains, anything was a luxury when compared to making an overland journey by foot, on horseback, in a kago, or by one of the few stagecoach lines then operating, but by the 1890s, matters had progressed to the point in Japan that issues of passenger comfort were being considered. As late as 1894, it was ill-advised to attempt to read at night in a typical Japanese passenger car, as Francis Trevithick noted when lamenting the low grade rape oil, inferior type of burners, and poor wick trimming in the standard oil lamps for lighting; this at a time by which most of the American and European passenger car fleets had long been equipped with the superior Pintsch compressed oil gas system, and many had been fitted with electric lighting. The first electric lighting only began a very gradual conversion of the existing fleet.

On another point of traveling comfort, Kadono Chōkyūrō observed:

“As regards passenger accommodation there still is plenty of room for improvement. When distances were short and traffic local, what accommodation there is was sufficient; but as at present the continuous lines or rails between Shimonoseki (Mitajiri) in the south and Aomori in the north reaches about 1,000 miles, a through passenger, unless of the most robust constitution, cannot undertake the journey without one or two stoppages for recuperation. Under the best circumstances, a railway journey over ten or twelve hours is tiresome enough (unless passed in sleeping), but when it comes to 1,000 miles without proper accommodation, one shrinks from the attempt. Refreshments are obtainable at almost every station, but travelers from foreign countries generally provide themselves with wicker baskets from the hotels, instead of relying upon station refreshments for subsistence.

In warming the carriage in winter, the old-fashioned, awkward hot-water foot-warmer is used. The heat from these usually proves to be rather pretense than an actuality, especially in the north.”

A foot-warmer was a large zinc or tin container, often wedge-shaped like a footrest, with a screw cap on one end, into which boiling water was poured. Kadono is speaking of the situation on Honshū, where British practice was in place. Trevithick agreed that the imported British institution of the foot-pan, which was provided only to first and second class passengers, was unacceptable, particularly in its total absence from third class carriages: “[T]he Japanese kimono is not a garment which offers great protection against cold when the wearer has to place himself upon a wooden railway seat, and unless provided with warm wrappers, which the majority of third class passengers do not possess, a long journey at night during the winter must prove a very trying undertaking.”

Of course, foot warmers were only good for as long was the water in them remained hot. Trevithick was mindful of “the inconvenience and annoyance to passengers of continually changing foot warmers on a long night journey” when he noted that a patent foot warmer using a newer chemical technology of acetate of soda in place of water could be adopted, which held its heat for 8 hours: nearly 3 times longer than ordinary water, which lasted only about 2½ hours. (Japanese railways by and large used plain water.) One can only imagine the scene in winter some two and a half hours after a train had gotten underway as a mad scramble ensued at the next station to exchange spent foot warmers for fresh ones. The use of foot warmers, of course, is a result of following English practice on Honshū. On Hokkaidō passengers fared better, as its American-style passenger cars had been equipped with a cast iron coal-burning stove for heat in each car from the beginning of railway services there. Steam heating wasn’t introduced until very late in the Meiji era, commencing in 1903, and then only slowly. The exception was the San’yo which had installed steam heat on all its express trains by 1904. Noted one weary American in that same year: “There is only one experience so cold and cheerless as a winter trip on some of the English railways—and that is a journey in the snow season on a train in Japan.”

Other areas where Japanese railways lagged behind their Western counterparts were in clear definition of their responsibilities and liabilities as common carrier vis-à-vis the traveling public, shortage of motive power, freight facilities inadequate to handle demand, and shipping delays. This latter had risen to such a level around this time that complaints were raised that lags caused a delivery time of from ten to fifty days for a journey that should have taken only one or two by rail. Such was the excess demand for railway shipment of goods that when one particular shipper asked for a discount from the Nippon Tetsudō, the general manager would not allow for any discount at all if the shipper shipped 10,000 tons of freight or 100,000 tons. Freight hauling concerns took second priority to passenger traffic for almost the entire Meiji era.

The Sino-Japanese War only exacerbated the situation. The writer W. E. Curtis recorded the flavor of passenger service at the War’s end,

“While the railway management in Japan is in many respects admirable, they have an aggravating way of changing the schedules of trains without the slightest notice. People never know when or why a train is taken off, or the hour of its departure postponed. Sometimes a regiment of troops coming home from the war [with China] will disarrange the whole service. A member of the ministry, or some high public functionary, may want to take a trip by a special, and the railway managers will take off one of the regular trains to accommodate him. Such incidents are occurring every few days, and of course someone always suffers annoyance in consequence.”

The introduction of rail technology to Japan brought with it improvements not always appreciated today. A case in point is the trolley shown in this postcard. Modern day readers are likely to assume that it is a street washer and in a sense, it is. But a clue to its real purpose is found in the broken English caption of “Powder Water Electric Wheel.” At a time when many of Japan’s roads and streets were still of unpaved dirt, they could be muddy quagmires in wet season. But in the dry season of summer, particularly on heavily-trafficked roads, the amount of dust created by that traffic could be prodigious. This trolley was Ōsaka city’s answer. Its purpose was to spray dusty roads with water during the dry months to make the dust lay and thus alleviate the problem until another pass was needed; surely a welcome improvement for many a nearby housewife or shopkeeper weary from dusting. In addition to keeping the air cleaner, the trolley also presumably cooled down many a young boy on a hot summer’s day who was bold enough to play trolley dodger.

* * * * * * * * *

By the war’s conclusion, railways were ever increasingly becoming an integral part of the lifeblood and social fabric of the nation and as the network expanded, the effects began to be felt throughout the realm. In remote villages, the pace of life, as in countless small towns in America and Europe, began to be marked by the arrival and departure of trains. Newspapers and periodicals arrived on those same trains, helping to form public opinions in a novel manner with a speed hitherto unknown. With the advent of small parcels service by the railways, many items previously out of reach began to become more easily available to the well-off. Foods hitherto unavailable gradually became within reach. All manner of consumer goods once difficult to come by in the provinces were in reach if a person was wealthy enough to order them. The foreign tourist and domestic traveler alike were given a reasonable hope of finding bottles of Bass India Pale Ale or cans of corned beef from the packing plants of Chicago on sale in even modest sized towns where only twenty years hence finding a live chicken to buy and cook for dinner was not always possible. In any given town, the railway station became both a hub of activity, a civic forum, and the backdrop before which many of the notable incidents of the day would play out. The writer Lafcadio Hearn recorded one. On June seventh 1896, a passenger train, probably piloted by one of the American-built 4-4-0s or Moguls then favored by the Kyūshū Tetsudō for passenger service, pulled in to Kumamoto station, which was mobbed with a crowd of people. Hearn was among them and recorded the event in his short story At a Railway Station. On the train was Nomura Teichi, a thief who was wanted for the infamous murder of a well-known and much respected Kumamoto policeman named Sugihara some years hence, and the news of his apprehension had spread rapidly enough throughout the city, which still had not forgotten the crime, that there formed a curious crowd to await the train’s arrival. Behind the ticketing gate in the throng that day was the policeman’s widow and his small son, unborn at the time of the murder. As the thief and his police escort moved through the wicket, the escort called forth for the wife of the fallen man, who approached with the little boy. At that point according to Hearn’s narrative, the escorting officer broke the silent tension in low and certain words; “Little one, this is the man who killed your father four years ago. You had not been born; you were in your mother’s womb. That you have no father to love you now is the doing of this man. Look at him—look well at him, little boy! Do not be afraid. It is painful; but it is your duty. Look at him!” The crowd stood silent as the boy did indeed look the man in the eye, gazing “with his eyes widely open, as in fear; then he began to sob; then tears came; but steadily and obediently he still looked—looked—looked—straight into the cringing face,” as the thief broke down, kneeling on the platform in contrition. As the man was brought to his feet he begged for pardon of the small boy and the crowd parted to make way, silent and touched. Hearn then saw “what few men ever see,... the tears of a Japanese policeman.” By the time it was written, Hearn’s short story could have happened in any one of an increasing number of small provincial towns and bears eloquent witness to the fact that by the 1890s, a railway station in Japan had unmistakably taken a central place of importance in civic life of the nation; no less than the depot did in small-town America.

By the opening years of the 20th Century, railways were starting to integrate themselves into the national psyche of Japan in all the ways they had in the West. This included new generations of children who grew up taking for granted forms of transport that their parents and grandparents thought of as revolutionary. In this obviously posed view, two young boys are seen participating in that process as they play with toy trains most likely imported from Europe. Typically, only the sons of a family of above-average means would have had such expensive toys in the Meiji era. On the blackboard is written the picture’s title: “Well... This time, let’s play with our toys!”

One of the most lasting examples of the integration of railways into the daily fabric of Japanese life from this time is “The Railway Song” (Tetsudō Shōka), written by Owada Takeki to celebrate the opening of the Tokaidō Line. The lyrics describe a trip from Shimbashi southward along the new line, with each station being the subject of a verse.

The first verse reads:

Kiteki issei Shimbashi wo

Haya waga kisha wa hanaretari

Atago no yama ni irinokoru

Tsuki wo tabiji no tomo to shite

A rough approximation:

With a single whistle-blow,

My train departs Shimbashi.

The moon, set low, o’er Atago,2

Goes with me on my journey.

The song became immensely popular and to this day continues to be a time-honored children’s song. The first few verses are by now as hoary an old chestnut of Japanese children’s pop-culture as “I think I can, I think I can, I think I can” is of American. Such was its popularity that when the San’yo line was completed to Shimonoseki in 1901, additional verses for each station along that line were added, and must have rendered the song utterly monotonous to sing in its entirety.

Naturally too, railways came to be the subject of the humorous side of daily life in Japan and did not escape public satire. In the comments to one of the lectures on Japanese railways which was given by Kadono Chōkyūrō at the local Asia Society, one worldly Hungarian wag, a certain Mr. Diósy, was recorded as having gone on record in the discussion that ensued after presentation with the tongue-in-cheek observation that:

“So well had the Japanese learned their lesson from our [Western] railway management that he was informed that at various stations in Japan, trains came in as much as forty-five minutes after the time advertised in the time-table. He also believed that many of the railway carriages were exceedingly draughty; and he had the authority of Professor Milne3 for saying that the names of the stations, as called out by porters, were perfectly indistinguishable, which showed that the best traditions of [Western] railway management were being carried out in Japan.”

Heating inadequacies and porter’s intonations notwithstanding, improvements continued apace. On May 25, 1899, the San’yo introduced Japan’s first dining cars on its premier trains, and a year later, the San’yo again took the lead with the introduction of the first sleeping cars in the realm. By 1900, Basil Chamberlain, Professor Emeritus at Tōkyō University, would write, “The arrangements of this line [the San’yo Railway] for the comfort of travelers are superior to those of the government and other private lines. It alone has had enterprise enough to provide dining and sleeping-cars.”

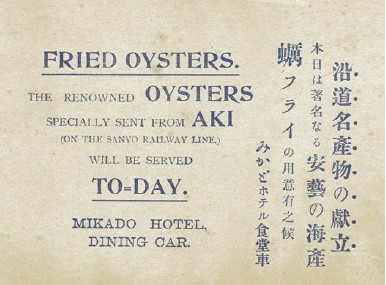

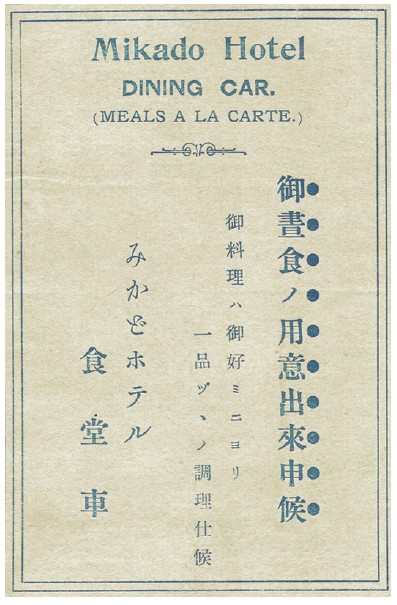

Pictured here is one portion of an early surviving San’yo Railway menu (announcing “We are ready for your Lunch”) from the San’yo’s very first years of dining car operation, before nationalization in 1906 rendered “San’yo Railway” an obsolete term, replacing it with the San’yo Line of the IJGR. Unfortunately, the other portion of the menu has been lost. The Kyōto-based Mikado Hotel assumed operation of the San’yo’s dining car services as a concessionaire in 1901, a position it held until 1938 when its operations were merged with those of another concessionaire. Aki oysters, a celebrated variety, have long been cultivated in the area around Hiroshima as a particular delicacy. The first laws regulating oyster cultivation in that area date back to the Tenmon period (1532–1542). The Aki oysters on the menu are an example of the San’yo’s efforts to make its service more appealing than those of the well-established Inland Sea steam boat lines against which it competed. Before delivery to the San’yo dining cars at the start of the run in Kōbe or Shimonoseki, the oysters would have been shipped in special closed box cars or vans, with louvered ends and sides and purpose-built racks of tray tanks containing saltwater to ensure live delivery.

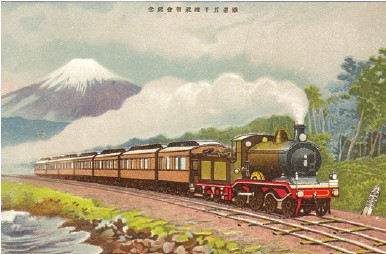

Finally, on May 27, 1901 the San’yo completed its mainline to Shimonoseki, Japan’s port of embarkation for the Asian mainland and for Kyūshū. As might have been expected, the San’yo immediately put a steamer service in operation with its own small steamers to cross the two-mile straits to the Kyūshū railhead at Moji. (The San’yo had previously put steamer services in place between Shikoku and Hiroshima.) By 1904, the San’yo could also boast that it was operating the fastest express trains in the realm, although at an average speed of just under 29 miles per hour, it was more telling of the poor speed of the other lines than any true boast of speed compared to average express speeds worldwide. Also from the San’yo Railway’s efforts came the first joint luxury express train in Japan, which commenced running between Tōkyō and Shimonoseki in 1905 consisting of all first and second class carriages, sleeping cars, a dining car (worked on a concession basis by the Union of Lunch Box Salesmen), and later possessing Japan’s first observation/lounge car at the end. The new super-express was called eponymously the Shimbashi– Shimonoseki Special Express. After the period covered by this book, when a sister express which included third class accommodation was added and named the Sakura (“Cherry Blossom”), the Shimonoseki Express, as it was then commonly known, would be rechristened the Fuji and the two would become the most celebrated of Japan’s pre-World War II expresses. Due in part to the speed restrictions implicit in a narrower gauge, the speed of the new express, while novel by Japanese standards, fell well short of the mark of American and European speed standards: the average speed was 47 miles per hour, while in the US and Europe, average speeds on the best express trains at the beginning of the 20th century were in the neighborhood of the 60 mph mark.

A writer who traveled on the San’yo Express at this time was surprised to learn that budget conscious travelers in first class could book a berth on San’yo sleeping cars on a half-night basis. First class berths were surcharged at 2 yen 50 sen for the entire night, but only 1 yen 50 sen for a half-night. Second class sleeping berths were evidently seen as enough of a bargain at 20 sen for the top berth or 40 sen for the lower, such that no half-night discount was offered.

1897 saw the importation of the first locomotives with the “Atlantic” 4-4-2 wheel arrangement from the Baldwin Locomotive Works in Philadelphia for use by the Nippon Tetsudō. In that same year, the Nippon Tetsudō took delivery of a type of locomotive that had never before been built in the world in any great quantity, but would prove to be such a versatile design that thousands of the type later would come to be placed on American railroads. There were significant coal reserves to be found in the Jōban coalfields that were situated along the new Jōban line of the Nippon, but the coal was hard anthracite, not top quality bituminous “loco coal.” When the line opened in 1897, the Nippon naturally wished to use the local Jōban anthracite coal rather than the costlier coal transported from outside the Nippon’s service area.

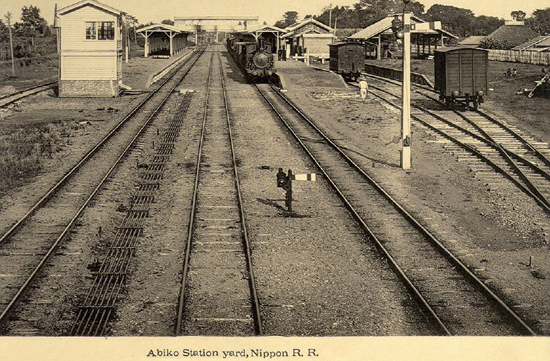

A short freight train trundles through the station at Abiko on the Nippon Tetsudō. Abiko is located on the Nippon Tetsudō Jōban line, approximately 40 kilometers from Ueno. The locomotive appears to be one of the Beyer-Peacock 0-6-0T tank engines imported starting in 1896 that would be designated the 1900 Class when absorbed into the IJGR’s roster upon nationalization. Note the short wheelbase compartment carriage in the station bay and the freight station consisting of nothing more than a canopied roof between it and the boxcar on the adjoining siding. A track ganger appears to be walking towards the station staff standing on the platform. Abiko, the junction from which the Narita Tetsudō departed for Narita, was deemed busy and significant enough to merit a full British style signal box. Over all, the British influence is clearly evident in the station configuration and signaling. In a scene unchanging worldwide, irrespective of era, the train has captured the attention of three small boys (to the right of the boxcar) who have stopped to watch as it passes by.

The wider Wooten firebox of the Atlantic type locomotive (a wheel arrangement suitable for fast passenger trains, which were comparatively light in weight) was well-adapted to burn such coal; hence the Nippon’s ordering a number of this locomotive type from Baldwin. However, the Nippon management also wished to have a heavy freight locomotive that would operate effectively on Jōban anthracite. Baldwin was consulted on this point as well, and it confidently promised it could satisfactorily design a locomotive that would perform suitably burning the Jōban anthracite, although no such designs existed at the time. The Nippon awarded it a contract for several, and Baldwin’s designer-draughtsmen took to the drawing boards. What evolved was a conventional “Consolidation” type 2-8-0 locomotive of the day—at that time, the freight locomotive of choice of many American railroads—but with a much larger and wider Wooten firebox. This firebox enabled it to burn Jōban anthracite, while at the same time produce a heating capacity equivalent to a conventional firebox that could only perform well on higher-grade “loco coal.” The result was a locomotive with roughly a comparable amount of pulling power, using coal of a lower caloric value. As the firebox needed to be much wider than the typical firebox, it could not be fitted between the rear driving wheels of the locomotive as was conventional; hence its place in the new design was behind the driving wheels, and a small set of wheels was placed beneath to support its weight. There had been a few scattered 2-8-2 type locomotives built earlier, but the result of the Nippon Tetsudō’s order was the world’s first class of 2-8-2 locomotives in any number. The type was dubbed the “Mikado” type to honor Japan and its Emperor and proved to be such a serviceable design that Baldwin capitalized on the design’s potential for other customers. Other builders followed suit, and eventually many thousands of these very versatile Mikado types would be appearing on railroads in America and throughout the world, where they quickly became the workhorses of freight haulage. The Mikado design, which had for its proving grounds the Nippon Tetsudō lines running through the Jōban antracite coal beds, would be destined to remain one of the world’s most common types of locomotives well into the 1930s.

Moves were afoot to establish locomotive manufactories and additional rolling stock manufacturers, not only for domestic purposes but also in anticipation for increasing demand that was expected to occur as China, Korea, Thailand and other countries on the mainland started railway building more extensively. First to be established were private rolling stock manufacturers, such as Hiraoka Kojo, founded by Hiraoka Hiroshi, the first Japanese Superintendant of Shimbashi Works. Then the first locomotive manufacturer, the Ōsaka Kisha Seizo Goshi-Kaisha, commenced business in 1896. It was founded by no less a personage than Inoue Masaru, who had retired three years before its founding from his post with the IJGR, and obviously saw his talents and reputation in developing Japanese railways as best applied in newer endeavors. The firm he founded would go on to merge with Hiraoka Kojo in 1901 to form the legendary Kisha Seizo Kaisha. Competitors also entered the field, and by the end of the Meiji reign loco builders such as Atsuta Tetsudō Sharyo (1896), the celebrated Nippon Sharyo (1896), and the world-renowned Kawasaki (an existing shipbuilder whose railway rolling stock manufacturing commenced in 1906) were on their way to making a name for themselves.

The days of the railway yatoi were almost at a close. From a high of some 200 yatoi who were first engaged in the first years of building, by 1882 that number had dropped to 21, and by 1895 had dropped to only 6, by which point, the day-to-day management of the lines was entirely in Japanese hands. The remaining half-dozen yatoi were in positions like that of the Trevithick brothers, who were among the last to go.

Partly as a result of the war with China, labor costs had risen, as had the prices of foodstuff and the cost of living in general. It was reported that the wages of coolies had risen by a factor of almost 100% between 1886 and 1896. By 1897 track or plate-layer gangs, normally consisting of seven men assigned to a two mile single line section, consisted of the following positions and wages: two at twenty cents a day, two at 24 cents a day, one at 27 cents a day, one at 30 cents a day, and one at 35 cents a day. Foremen for these gangs normally were assigned sections ranging from ten to twenty miles and were paid the equivalent of 40 to 75 Mexican cents per day accordingly. While prices and wages were rising generally across Japan, railway wages were stagnant on many lines, and labor unrest ensued, first in the paint shops of Shimbashi, but later notably on the recalcitrant Nippon Tetsudō, where one of Japan’s first and most effective major labor strikes occurred in 1898. The strike was noteworthy enough to merit mention in the foreign press. The Nippon Tetsudō had been the subject of complaints of poor treatment of its employees for some time and had in fact lowered the pay of engine drivers and firemen. Quite naturally in a time of rising cost of living, the affected staff had repeatedly petitioned for higher wages, all to no avail, to the point where they formed an association to militate on their behalf. Management responded by terminating the employment of the employees it perceived to be the primary instigators. The ploy backfired and only served to stiffen the resolve of the rank and file who began circulating strike notices to all stations up and down the line at the end of February 1898. Traffic movement came to a standstill. Part of the strike resulted from the feudal mindset of management, many of whom came from the former Samurai class and still comported themselves with the attitudes by which they had been raised. At the time, the IJGR had a four-grade ranking system, which many other railways, the Nippon included, followed. In descending order the grades were titled Chokunin-kan, Sōnin-kan, and Hannin-kan roughly translated “Imperially Appointed Official,” “Official Appointed with Imperial Approval,” and “Junior Official” respectively. At the bottom was a fourth class that didn’t even merit an official class title, consisting of rank and file workers. (To make matters worse, hannin was pronounced exactly like another word using different characters that meant a suspect or criminal, with all its negative implications.) Out of this arose friction, as stationmasters and conductors were classed as hannin, while engine drivers and firemen were classed in the nameless bottom ranking. This was not a distinction without a difference: there were more liberal travel allowances, perquisites, and the like that were allowed to hannin. During the Sino-Japanese War, the contrast in classes was made even sharper, as many of the hannin rank received special commendations and awards, as particularly exemplary performance records merited, but few rewards were distributed for the many extraordinary efforts put forth by the drivers and firemen.

A Dubs product ordered for and used by the Nippon Tetsudō, despite the caption. This 4-6-2T tank locomotive class consisted of four members that were introduced in 1898. The Nippon Tetsudō remained partial to British locomotives long after the other major railways had become customers of American locomotive builders in ever increasing degrees. This locomotive came equipped with a steam actuated reversing gear, something of an innovation for the day. The confusion in the foreign press of Victorian and Edwardian times as to which railway had purchased locomotives was due to the Japanese Government, through the Railway Bureau, acting as a purchasing agent on behalf of private railways, which the technical press of the day mistakenly assumed meant automatic use by the IJGR. The locomotives were designated as the 3800 Class upon nationalization.

Twenty-six of these neat little Columbia type 2-4-2T tank locomotives were imported in 1898, the last year of importation of American examples of this particular type of small locomotive to Japan, although importation of British-built A8s would continue up to 1904. Schenectady was the builder, and the locomotives would become IJGR Class 900 under the 1909 numbering scheme. This builder’s photo however shows a class member “as-built” for the Nippon Tetsudō, complete with English language tank-side road name. Liveries such as this typically lasted no longer than the first re-paint, however photos do exist of a Nishinari Tetsudō British-built A8 locomotive with the road name spelled out in the Romaji alphabet. As the style of the lettering on the Nishinari tank loco was American, not British, the lettering was almost certainly applied in Japan, probably as a public relations device at a time when anything foreign was faddishly seen as progressive.

A builder’s photograph of one of the Hannover 2-6-2T “Prairie Tank” type locomotives built in 1904 for the Nippon Tetsudō, a neat hybrid of British and German design practice. Six of these locomotives were imported from Germany for mixed service and were assigned Class 3170 during the 1909 renumbering.

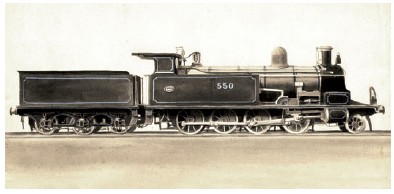

The Nippon Tetsudō (again, not the IJGR as captioned) ordered two of these small-drivered 4-4-0 locomotives from Dubs in 1898. They would be designated as Class 5830 upon nationalization. The two-truck tender used in this class is unusual and seems almost disproportionately large compared to the locomotive. Most of the tenders for the British-built locomotives were rigid wheelbase six-wheel tenders. As the Nippon Tetsudō was never known for particularly fast running even by the slow Japanese standards of the day, the small diameter of the drivers would not have been unusual. Note the wide firebox. In the decade before Nationalization, the Nippon Tetsudō began to order some forward-looking designs, and became increasingly sensitive to locomotives that could burn the anthracite coal that was available in the Jōban region through which it ran once its Jōban line was opened in 1897.

A relative comparison is made in this general arrangement outline between one of the earliest tank locomotives and the world’s first mass-produced 2-8-2, built in 1897 by Baldwin for the Nippon Tetsudō to burn an anthracite coal from the Jōban coalfields situated close-by the railway’s main line. These locos were designated Class 9700 on nationalization. The 2-8-2 locomotive type was dubbed the “Mikado” wheel arrangement in honor of the Meiji Emperor; a name that came to be used throughout the English speaking world as the shorthand term for this versatile wheel arrangement. From a 1903 pen and ink drawing by Kashima Shosuke.

The Nippon Tetsudō took delivery of this Mallet compound 0-4-4-0T locomotive from the German builder Maffei in 1903. A slightly different sister locomotive was ordered for comparison. Together, these two examples were the first Mallet type locomotives imported to Japan. The design was a natural for Japanese operating conditions with its four cylinder drive in place of the usual two, and articulated front power unit to negotiate tight curves necessitated on mountain lines. They were a type well-suited for mountainous freight haulage or banking duties. The locomotives were 1067mm versions of similar locomotives that had been built for the Royal Bavarian State Railways, but were heavier, had larger fireboxes, and larger water tanks, all of which resulted in slightly greater tractive effort. Nationalization cut short further purchases, and when the IJGR began purchasing Mallet locomotives, it was for much larger Alco 0-4-4-0 tender locomotives from the US for heavy freight hauling.

Another grievance called for the removal of certain individuals in higher management, due to the fact that some ¥60,000 had disappeared from the company books, and rather than pursue the individuals in management who were responsible, the company made good the embezzlement loss on its books by drawing down the fund put aside for employee bonuses. The company’s wage structure was also the cause of dissatisfaction: for workers who earned less than ¥25 per month (such as drivers and stokers) the rate of the first pay increase on promotion was ¥2½, while for those making over ¥25 per month, such as a typical hannin, the first pay increase rate was double at ¥5. Similarly, if one was paid on a daily basis, if a person was making a daily wage of less than 90 sen, the rate of first pay increase was 5 sen, while those paid over 90 sen were increase by double that amount. In short, the wage scale discriminated against the lower-paid workers, when, in 1897 (at a time when wage levels elsewhere were rising at rates of 30–50%, and the cost of living had risen by almost as much), mere office clerks who were trained in a matter of months received proportionately a larger pay increase than engine drivers who took years to train and who had much heavier responsibilities for public safety. The discontent was palpable: so much so that the drivers and stokers petitioned management with their grievances, only to have management respond by firing the individuals perceived to have been instrumental in presentation of the grievance. Rather than cowing the workers, this only resulted in a countermeasure, as the rank and file’s response was the forming of an association known as the Treatment Improvement Association, Taigū Kaizen Kumiai (待遇改善組合).

An interesting comparison can be also be made between the Kōbe-built F1 (later 9150) class Consolidation locomotive for the IJGR shown here and the Baldwin-built F2 Class locomotive shown following this image. The lines of this locomotive bear a vague resemblance to the contemporary “E Class” locomotives of the London North Western Railway. Side tanks on a tender locomotive are a somewhat unusual feature worldwide, but were an obvious advantage both in adding to a locomotive’s range between water stops and additional weight on the locomotive’s driving wheels, increasing its tractive effort. The class was built between the years of 1900 and 1908. The device behind the chimney was used to compress air in the cylinders when going downgrade with the steam cut off. It assisted in maintaining the British system vacuum brakes, which were used on Honshū, and would have been very useful, given the general inferiority of the vacuum brake system over American Westinghouse airbrakes, particularly in a mountainous land such as Japan. They were much in vogue on various Japanese locomotive classes used on mountain services of the day. The painting is a watercolor by the Keio University student Kashima Shosuke, circa 1904, and seems to indicate that the lining and numbering of these locomotives was blue.

When confronted anew with the demands of the new organization, management employed the same tactic of firing the key figures in the Treatment Improvement Association, and this act would proved to be the watershed event. Within a short time after the dismissals, work stoppages spread up and down the line, and public opinion turned in favor of the workers after the press had reported enough of the facts to have generated public interest. After about two weeks of traffic suspension, management capitulated in large part to the demands. Drivers and stokers were raised to hannin class, on par with stationmasters, they were given less condescending job titles, there was wage structure reform, and all the strike participants, except the two chief agitators, were re-in-stated. Of course the two agitators who sacrificed themselves to benefit the greater good went on to become some of the founding members of the Japanese labor movement, and indeed this strike went down in the annals as having pride of place in the history of the organized labor movement in Japan.

Frances Trevithick likewise admitted that there still remained much to be improved. Speaking in 1894, he noted that the case of staff being on duty long hours without adequate periods of rest was an area in dire need of amelioration. Amusingly, another area where Trevithick saw room for improvement was the need of train crews to do a proper stop before descending a grade to pin down the brakes of the freight cars in their train (operating on the British system, there were no freight car brake wheels to set the car brakes, by walking along the rooftops of moving cars as American brakemen did... a train would need to come to a full stop before the downgrade, and the brakemen would walk along the train, fixing the brakes using the brake lever found on the under-frame of every so many wagons as were appropriate) instead of relying simply on the brakes of the locomotive, tender (if any) and brake van (caboose) where the brakemen rode.

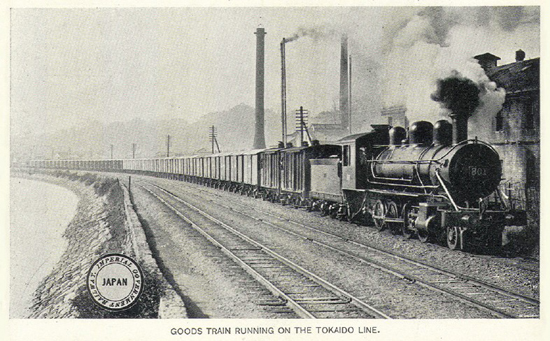

The length of the freight train in this busy scene suggests that is has been specially posed for the IJGR photographer. The mere fact that the locomotive bears running number 801 would date the view to before the 1909 renumbering, but in fact it is known to have been taken in 1905–1906. Number 801 was a Baldwin Consolidation-type of the F2 or 9200 class. The view is most likely taken in the vicinity of Kawasaki. Note the heads of two brakemen peering out of the windows in the brake compartments of the first two boxcars behind the tender. Freight cars with brake cabins were characteristic of Japanese freight rolling stock.

By roughly mid-point in the decade, America has started to become competitive in the manufacture of steel rails, and the first large orders from Japan for steel rails from US rolling mills dates from around this time. The New York Times first mentioned the trend in the spring of 1896, remarking on an order for 500 tons of rail from the Illinois Steel Company that was set to be shipped on the steamer P. Sawyer. By summer, it was interviewing Iwahara Kenzo, the Mitsui Co. purchasing agent who had come to negotiate rail contracts with Carnegie Steel, this time for almost ten times the initial amount at 9,000 tons. By the time Joseph Ury Crawford was mentioned in its pages in late November, the amount he had been authorized to purchase on behalf of the Japanese Government was 15,000 tons. All this within the course of a single year—a year coincidentally that saw Matsumoto Sohichiro, Inoue’s successor at the Railway Bureau come to the US on a fact-finding study of the American railway system. Matsumoto’s report was favorable and receptive to further orders of American-made equipment. Not surprisingly, American locomotives continued to supplant British-built competitors in point of price and delivery times, in part because the British manufacturers were contentedly happy with their full order books at the time and were not inclined radically to expand capacity. British manufacturers were somewhat more accustomed to building locomotives to drawings supplied from the Chief Mechanical Engineer’s offices of the particular railway than American locomotive manufacturers, who were more accustomed to receiving only performance specifications and preparing design drawings from those parameters in-house for the customer’s approval. The latter method was attractive to Japanese railways, allowing them to shift the design tasks (for which there were few domestic candidates) and research and development costs to the builder. In 1898, when market demand on British locomotive production capacity was reaching a peak, British builders couldn’t keep up with domestic demand, let alone demand from abroad, and locomotive delivery dates were being quoted some two years from the order date for large orders. Against this, American builders such as Baldwin were able to turn out two locomotives per day and could ship an order as large as 40 locomotives in eight to ten weeks. A New York Times headline under date of February 19, 1905, reported that Baldwin had just received the largest order for locomotives by any foreign government in the firm’s history: 152 locomotives having been ordered by Japan. According to the reckonings of the day, an American locomotive could be bought for about 20% less than a comparable British locomotive, once shipping costs were factored in. Despite the superior quality and claimed economy of the British product (American locomotives tended to burn more coal to pull the same load) it was understandable, and perhaps unavoidable, that the period from 1895 to 1910 was the period of American locomotive ascendancy in Japan.

The Nara Tetsudō opened in 1895, directly linking the ancient towns of Nara (Japan’s capital from 710 to 794) and Kyōto, with a roster of twelve locomotives, of which this example was one. The locomotive is one of the very few Japanese locomotives that did not originate from Great Britain, Germany or the United States, having been built by Switzerland’s well-known Winterthur works. No. 7, shown as delivered, ran for ten years as a Nara locomotive before the Nara Tetsudō was absorbed by the Kansai Tetsudō in 1905, giving the Kansai (which had already reached Nara) access to the city of Kyōto. Nationalization the following year cut short the potential for the renewal of competition with IJGR Tokaidō trains respecting the Kansai’s new Kyōto/Ōsaka and Kyōto/Nagoya routes.

With the opening of the Tokaidō line and the revision of the Extraterritoriality Treaties, the scrapping of the internal passport system of travel for non-Japanese would eventually occur—but not until the new century had opened. Nevertheless, by the mid-1890s the internal passport system was becoming a matter of routine. An English traveler in 1898 described his experiences in the following words:

“Arrived at the railway station, we are received by an officer in full uniform, who will direct sundry menials clad in butcher blue kimonos, but bare as to their hairy brown legs, to carry our luggage into the station while he conducts us to the booking office. The gentleman (usually in spectacles), who smiles benignly at us through the diminutive pigeon-hole, then disburdens his mind of a polite but totally unintelligible sentence in Japanese. A dim recollection of the hints of the guide-book leads us to correctly surmise that he is making affectionate inquiry for our passport. This indispensable document is not the banknote-looking paper, signed ‘Salisbury’ in one corner... It is a State document obtainable only at the Japanese Foreign Office.... [I]n most of the large seaports of Japan there exists a portion of the town known as the “Foreign Concession,” within which all foreigners... may reside... Within twenty-five miles of this concession, but no further, may the foreigner direct his wandering steps. To advance one yard outside this special district, known as the ‘Treaty Limits,” is a criminal offence, unless the individual be armed with a “passport.’... It is easy of acquirement, and of great service. At the Japanese Foreign Office are drawn up lists of places arranged in the form of tours, separate passports being issued for each series. The traveler selects the itinerary for which he desires a passport from one of these lists. The routes cover all the places of beauty or interest in Japan, but no passport can be extended, nor can a traveler deviate in any particular from the tour laid down for him therein. A passport is valid for three months, and each traveler before obtaining one has to sign a declaration stating that he is traveling ‘for the benefit of his health.’ This declaration is of a sufficiently elastic nature to prevent anyone from doing violence to his sense of veracity in subscribing to it. Three large seals depend from the passport in an imposing manner. One of the conditions of issue is that this document shall be returned to the Foreign Office immediately upon expiration or upon the holder leaving the country. Failure to comply with this rule entails very heavy penalties, and also the certainty of a refusal should an application ever again be made for a passport at a subsequent date.”

Despite the strictures and inconvenience of the Internal Passports for foreign tourists and resident aliens, with the extension of the railways to many parts of Japan by the mid-1890s, a modern tourism industry began to germinate for native Japanese and foreigners alike. Japan had had tourism for centuries. Visits to Mt. Fuji, the Itsukushima Shrine, Kyōto and its many sights, the Tokugawa mausoleum and the scenic beauties of Nikko were as popular before the advent of the railways as they were after. As early as 1881, according to the Tōkyō Eiri Shimbun, trains on the Shimbashi line had to run until as late as 2:30 in the morning from the stop nearest Ikegami Temple to accommodate crowds who had been there for festivities. Pilgrims had been streaming to Japan’s holiest site, the Grand Shrine at Ise, since the earliest feudal times; centuries before the Sangu Tetsudō (lit. “Shrine-bound Railway”), the epitome of the Japanese extension line, was established in 1893 to transport pilgrims from the closest station on the Kansai Tetsudō to the shrine precincts.

It would be difficult to conjure a photograph that expressed the aesthetic of Meiji-era railways better than this view, showing a small A8 style 2-4-2T tank locomotive of the Sangu Tetsudō pulling its train of three box cars, a string of four-wheel passenger compartment carriages, and one sole first/second class bogie carriage, positioned in the center of the train as was typically the case in Meiji-era train consists, over the Miyagawa Bridge on the approach to Ise, home of the most sacred Shintō Shrine in all Japan. The Sangu opened Miyagawa Station, across the eponymous river from Ise in 1893, but it wouldn’t be until 1897 that this bridge had been completed and the line could run the remaining few miles into Ise proper.

With the opening of the Tokaidō line and the rapid extension of the major trunk lines of the Nippon, San’yo, Kyūshū and Kansai railways in the 1890s, many of Japan’s points of interest were placed within convenient and feasible reach of both native and foreign travelers. Before 1880, a typical Westerner visiting Japan would probably have debarked at either Nagasaki or Yokohama, visited Tōkyō and environs, proceeded to Mt. Fuji and the Great Buddha at Kamakura (both of which were in reasonable proximity to Yokohama) and if adventurous, would have culminated the sightseeing with a trip to the impressive tombs of the Tokugawa Shōguns amidst the scenic grandeur of Nikko, as one of the best maintained roads led there from Tōkyō and it could be reached via one of the earliest stagecoach lines in the realm. The more seasoned travellers would have gone to the length of obtaining an internal passport enabling them to take a steamer to Kōbe/ Ōsaka, and then proceed to visit the ancient cities of Kyōto and Nara. Rarely did a typical foreign tourist travel farther afield.

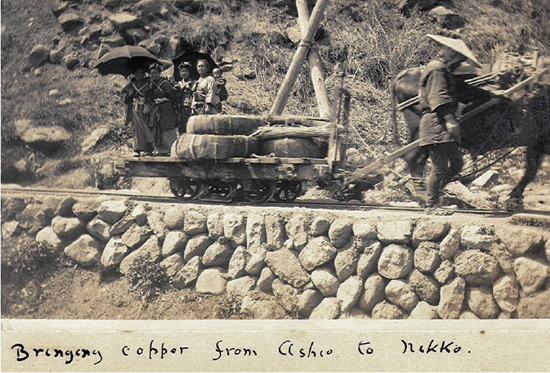

By the middle of the 1890s, the situation was changing. Nikko was at the end of a short branch line leaving the Nippon mainline from Utsunomiya that was completed in 1890. Nara, the ancient capital of Japan with its giant Buddha and 8th century Horyu-ji Temple complex (where the oldest wooden buildings in the world are to be found to this day), via the Kansai Tetsudō and the new Nara Tetsudō, and Kyōto both were accessible by rail. Fuji stood along the Tokaidō line, and resort towns in its vicinity such as Miyanoshita were already publishing brochures and guidebooks in English aimed at the foreign market. The Great Buddha of Kamakura was rendered a mere day-trip by train from Tōkyō or Yokohama, as was the Grand Shrine of Ise from Nagoya. Later, as the San’yo mainline was completed, the celebrated sites along the Inland Sea were more easily accessible: the scenic town of Onomichi, the historic sites of the great naval battles of Dan-no-Ura and Ichi-no-Tani, the Itsukushima Shrine at Miyajima, built partially over water with its celebrated “floating” Torii gate. At Shimonoseki, the San’yo built the San’yo hotel, which it operated as an adjunct operation. Similarly, the Kansai Tetsudō’s president invested in construction of the celebrated Nara Hotel in Nara, one of Japan’s top tourist destinations, situated on the Kansai’s main line, as a joint venture with the owners of the Miyako Hotel in Kyōto. Both were adopting the innovation of the railway hotel that had proven profitable in Europe and North America and had helped to stimulate tourism.4

Even the little Kyōto Tetsudō made a bid for both the domestic and foreign tourist markets: it touted its proximity to the famed Kinkakuji (Golden Pavilion) of Kyōto and white water boat rides over the Hozu river rapids departing from its Kameoka station with postcards and tourist brochures in both Japanese and English; this at a time when the road was only 38 miles long (the railhead had only reached Sonobe, less than halfway to the railway’s intended terminus on the Japan Sea at Maizuru) and the railway only possessed twelve locomotives on its roster. The grottos at Gembudō soon became accessible with completion of the Bantan Tetsudō and with that line’s completion and the building of the IJGR Inyō-Renraku line, Japan’s second-most sacred Shintō shrine at Izumo became accessible. Hot springs and hill towns (to escape the stifling humidity of Tōkyō summers) were then fashionable among well-to-do Japanese and foreign residents. Karuizawa,5 earlier mentioned, became a popular summer resort for the well-to-do nestled high in the mountains northwest of Tōkyō on the Shin’etsu mainline. Various hot springs (“Onsen”) in Shikoku came to have a little narrow gauge train leading to them. One of the most visited stations on the little Dōgo Tetsudō in Shikoku was the local hot springs. Prior to the advent of railways, a good day of hearty tourism in Japan would result in an average of between 18 and 25 miles covered, depending on terrain and the passability of un-bridged rivers. This was often by foot or on horseback, rain or shine. The prospect of traveling eight hours in pouring rain on foot or atop a packhorse to accomplish only 20 miles of travel was alone enough to discourage travel among all but the most stalwart. Given the alternative, a train trip from Tōkyō to Kōbe that included some 70 stations stops, some of which were quite lengthy, wasn’t as bad a prospect as it might seem by today’s standard. The fastest express in the mid-1890s cut out twenty of the 70 odd stations on the Tōkyō–Kōbe route, but still only averaged 12 miles per hour. Nevertheless, the results of the first steps of tourism development were remarkable, stirred notably by the domestic market. By the close of the nineteenth century, the first steps taken to develop what we would see as the germ of a modern tourism industry were showing promising signs of success. Indeed by 1902, more than a hundred million passenger tickets were sold annually in Japan, an increase of more than double the amount sold in 1896.

Ever the innovator, the San’yo Tetsudō was not afraid to bid for the foreign tourist market, as shown by this advertisement in English. When this ad first appeared in 1904, during the Russo-Japanese War, the progressive line had put in place three steamer routes connecting with Shikoku and a ferry route to Kyūshū. It could also state that all its express trains (four in number) were electric-lit, steam heated, and furnished with sleeping and dining cars, a boast that other railways in the realm would have been hard pressed to make. Other interesting traveling arrangements are evident in the advertisement. One can’t help but wonder how many foreign visitors chose to visit Matsuyama for the purpose of seeing a P.O.W. infirmary “where the wounded Russians are nursed.”

Once the Bantan Tetsudō (from Himeji on the San’yo Tetsudō) and the IJGR’s Inyō-Renraku (later to be re-named San’in) line to Tottori had been opened, the basalt grottos at Gembudō (the entrance is visible in about the center of the photo) were easily accessible by rail. Gembudō station itself opened in March 1912. This postcard view shows an IJGR express train of late Meiji clerestory coaching stock pulled by a British-built 4-4-0. The rubber stamp on the card would have been put on it at a particular destination, as a souvenir.

The San’yo also operated a ferry service to Pusan, Korea as part of its ever-expanding services. Realizing that it was the gateway to the Asian continent for the bulk of the Japanese population of Honshū, it put into service the steamer shown in this card, presumably the Iki Maru. The card evidences a certain whimsy in its train motif with its truncated locomotive. Relatively few non-government railway postcards were printed before nationalization.

Traveling was still quite far removed from what the present day person would imagine. Take as an illustrative example the further travels of Charles Taylor, on the Nippon Tetsudō when he traveled in the mid-1890s during a particularly severe typhoon and flooding season:

"At last we arrive, by grace of heaven, [after considerable rain and difficulty by mud-swollen local roads] full of pains and aches, at Motomiya Station6 in time to take the 2.57 P. M. train to Sendai, having been four hours and one-half coming eighteen miles [on foot, due to mud that prevented travel by rickshaw]. At the station we learn that the bridges are washed away, and the railroad damaged as far as Aomori; also that no southern trains from Tōkyō had arrived at this station since the night before last, as the bridges on that section of the road are also unsafe.... While I am waiting for the train, the people gather about me in large numbers, gazing intently in my face and watching every movement, until this kind of free exhibition becomes too much for me, and I request the station master, through my guide, to allow me to enter the enclosure, hoping there to escape the curious throng. But even here [on the station platform, behind the ticketing gate] I am not free from their inquisitive stares. They stretch their necks, and some of them climb on the fence, smiling at my oddities, or standing spellbound at the strange sight. What a relief to see the train approaching to relieve me from my very annoying position. We take second-class tickets to Sendai. The third-class compartments are crowded with natives, and the comforts are limited... there are no conveniences on the third-class cars, while many of the second-class cars have toilet rooms.” [Elsewhere he labeled the train in which he rode as the Nippon’s “Anti-Express” Train due to the slow speeds encountered...]

On arriving at Sendai, he learned that though travel to Aomori on the Nippon Tetsudō was no longer possible due to wash-outs, and so he worked his way back southward by another route, to connect up with the Nippon Tetsudō at another point.

“We walk about a quarter of a mile [along the road from the point where his rickshaw and the rickshaw carrying his baggage both have bogged down] over mud and stones till we come to a swollen stream, the Furussata, generally a small and unpretentious current, now a rapid river enlarged by the recent rains. We cross it by another [ferry] boat. While waiting on the bank I perceive, not far away, the wreck of the large railroad bridge which spanned this water only a short time ago. In ten minutes, we are safely landed, over shoetops of mud. The river has subsided six or eight feet since yesterday, otherwise we would have been unable to cross it to-day. We walk half a mile on solid ground, then resume our jinrickshas, bid a courteous Japanese officer farewell, and start off on a six-mile ride to Utsu-No-Miya [sic] Station, arriving at 10.10 A. M., just as the bell rings for the train to start for Nikko. My guide unselfishly begs me to enter the train and go on to Nikko, while he will await the arrival of the jinricksha with our baggage and follow on the 12.30 train. But I tell him I will not desert him at the last minute; we will both wait. He urges me repeatedly, and finding me persistent in my refusal asks the guard if he cannot hold the train a few minutes till the men [rickshaw runners with the baggage] appear. The obliging guard consents to wait ten minutes, saying that beyond that he dare not delay the train. The greatest interest is manifested by all the railway officials in the arrival of our [baggage] jinricksha. Some of the passengers, wondering what is wrong, get out and ask questions. A crowd quickly gathers at the station and around me. Minutes pass and no sign of the jinricksha. Finally, when it is within two minutes of starting time the men and wagon are seen in the distance. A shout of joy goes up, and a half-dozen men from the station run at the top of their speed to meet the tardy jinricksha, and all together fairly make it fly to the station. It is exactly twenty minutes past ten when the baggage is placed on board the train. Another glad shout fills the air. I bow and smile and try to thank the people for their good-will, and they bow and bow, and we are now steaming along in comfortable cars to Nikko. I think often of this incident, as well as of many other kindnesses shown to us by these good-natured people, and wonder would an American train wait a traveler’s convenience in any State in our Union?”

[After further rain delay at Nikko Taylor resumed his trip...] “After a rest of a couple of days we take up our regular plan of travel, proposing to leave here to-morrow for Tōkyō. It has been raining in Nikko for the past five days, and is still raining. We learn that the railroad between Nikko and Tōkyō is badly washed [out], and in some places covered with water to a depth of ten or twelve feet, and that passengers to the latter city are conveyed by boat over the breaks in the road and across the rice fields to places of safety; also that you can go to Tōkyō in ten hours, three of which are by boat. A boat capsized this morning and its occupants were thrown out, but none of them were drowned. We are hoping for more favorable reports, but will, in any case, attempt to reach Tōkyō to-morrow by the early train. We arise early and find the sun shining brightly, as if to give us a good send-off. We leave Nikko by the 7.30 train... We arrive at Utso-No-Miya Station, where we change cars, and in about twenty minutes take another train, which carries us to the village of Nakada. We can go no further by train, for although the water is subsiding in other places the tracks here are under three or four feet [of water]. Large sampans await us, and taking our places in one of these, with other passengers, we are sculled to a temporary station provided by the railroad company.... The temporary station is made of a canvas stretched over long poles to protect us from the sun. Benches are here, made of rough boards. There are fully four hundred people here awaiting the arrival of the train... We have waited here since 11.45 this morning, and it is two o’clock before the shrill whistle announces the approaching train, and an engine draws a long line of empty passenger coaches up beside the station. Then follows a comical sight. There is a great scramble for the cars. Some of the people, in their eagerness actually jump through the windows.... And now they are all in and we are off, really off, for Tōkyō. We cross the Tone-gawa on a fine iron bridge, which was, several days ago, under thirteen feet of water.”

Due to its geographic location, the 38 mile long Kyōto Tetsudō was better situated to exploit the tourist market than some railways. Early in the 20th Century it produced this brochure (the front cover and first two pages are shown) for English-speaking clientele, focusing on white-water rapids boat rides on the Hozu river. In an era when bicycling was a popular new fad, the railway encouraged bicycling excursions by carrying passengers’ bicycles free of charge.

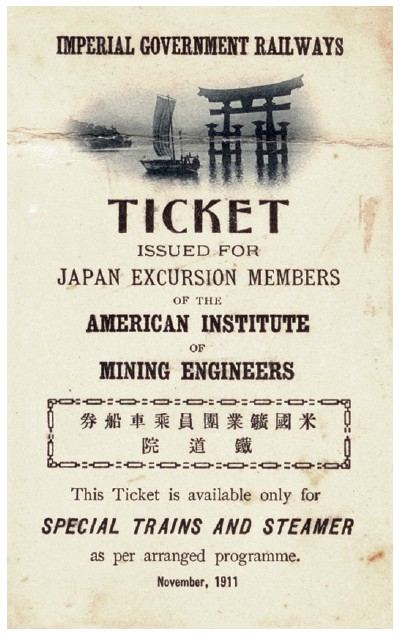

By November 1911, when conventioneers of the American Institute of Mining Engineers visited on a special excursion following the conclusion of its San Francisco convention, Japan had become less of a destination for only the super-rich foreign visitor or the adventurer than it had been only decades before. But visits by foreign delegations were still not so routine that they did not merit the issuance of a special commemorative ticket. This well-worn memento shows the so-called floating torii gate at Miyajima, one of Japan’s most recognized tourist icons, visited by the AIME members after stopping at a mine in the Shikoku region. The Miyajima visit occurred while en route via Inland Sea steamer to inspect the Yawata steel complex in Kyūshū. (Curiously, the surviving AIME official itinerary does not list any mine visits for Kyūshū.) The delegates returned northward by rail, visited copper mines in the Ashio vicinity, were officially hosted by Baron Eiichi Shibusawa, were fêted with municipal ceremonies in Tōkyō, Kyōto, Ōsaka, and Kokura, and were treated to receptions by the industrial houses of Mitsui and Sumitomo, both of which were actively involved in various mining ventures.

The United Kingdom’s renowned Royal Navy China Squadron visited Japan in October 1905 on a congratulatory and goodwill visit at the end of the Russo-Japanese War and its arrival was fêted as way to further the Anglo-Japanese Alliance. Two railway passes are shown from that visit. The Kansai Tetsudō treated the Royal Navy to an excursion to the ancient city and former Imperial capital of Nara with its giant Buddha and famed domesticated deer that roam the city freely. Minatomachi was the Kansai’s own Ōsaka terminal, from which the special departed, but the pass-holders could take a regular Kansai train from Ōsaka Umeda, into which the Kansai apparently also had running rights, and change upon arrival at Minatomachi. The Kōya Tetsudō offered trips from it’s Shiomibashi terminal in Ōsaka to Nagano (present day Kawachi Nagano), south of the city, from which the Kanshin-ji and Kongō-ji Temples could be visited.

Like Taylor, many a foreign visitor praised the level of personal service encountered on Japanese railways. W. E. Curtis, writing in 1896, was similarly impressed with the level of service and dedication of Japanese railway employees: