EPILOGUE: 1913–1914

Tōkyō Station

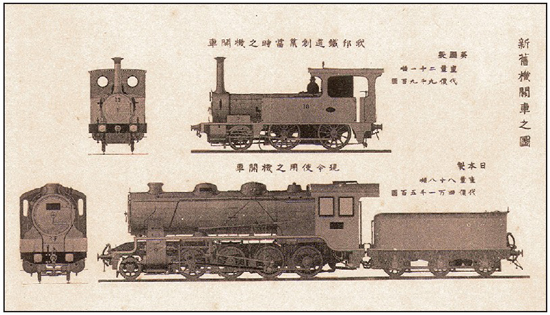

Juxtaposed here are two IJGR locomotives, one of the first ten locomotives imported in 1872, running number 13, built by Sharp Stewart compared to the latest locomotive of a family introduced by the IJGR in the last year of the Meiji reign, the ubiquitous 9600 class, a Consolidation type designed for heavy mountain traffic, many of which survived to the end of steam service in Japan.

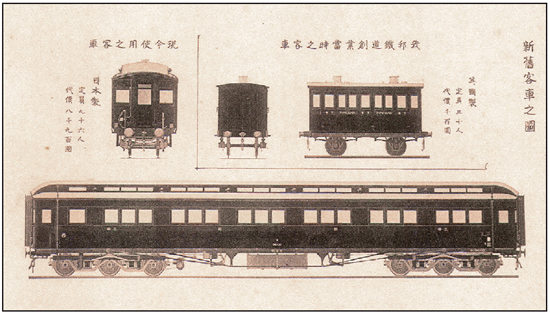

A comparison of the coaching stock at the beginning and end of the Meiji era, the first being one of the 15 foot third class carriages that were used on the Kōbe-Ōsaka line on its opening in 1874 while the later shows the latest clerestoried wooden body third class stock circa 1911, with vacuum brakes, electric lighting and six wheel trucks.

At the time of the Meiji emperor’s death, the IJGR’s standardized locomotive scheme was finding its stride. The IJGR designer-draftsmen had put behind them production of the 6700 Class and the two preliminary classes that lead to the 9600 Class. They next turned their attention to a locomotive that could be useful on heavy, fast passenger trains that exceeded the weight of the trains the 6700 Class was capable of handling. The Mogul wheel arrangement was chosen for the new design. The first IJGR locomotive design entirely of the Taishō era rolled out of the erecting shops in 1914. Eventually, the members of this design came to be designated the 8620 class, a modern, superheated Mogul with 1600mm drivers and Walschaert’s valve gear. The class proved to be a good steamer, very versatile in service, and as with the 9600 Class, a number survived to the end of steam on what had become the JNR, class survivors which would be preserved and used on steam-hauled special trains.

In April of that year, the wife of the Meiji Emperor, the Dowager Empress Shōken died, and once again the IJGR was called upon to provide a state funeral train for the final trip to Kyōto.

As Ōsaka station already had been rebuilt, and the central station in Tōkyō was underway, plans were also put in place to expand and rebuild Kyōto station, whose original building from 1877 was dated and inadequate to handle the increasing crowds of passengers that were passing through its ticketing gates. A new station was designed, the yards reconfigured, and the results opened in 1914. The new Kyōto station was the most modern in the realm in respect of appearances, a transitional structure squarely between Lutyensesque Edwardianism and the coming modernism of the 1920s.

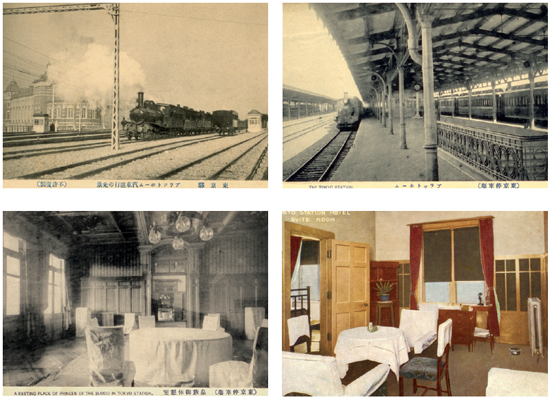

The capstone of Meiji era railway development was unquestionably Tōkyō Station, one of the architect Tatsuno Kingo’s most famous works. Started in 1908, it wouldn’t be completed until two years after the Meiji Emperor’s death. This postcard shows it shortly after it had been opened. The unique octagon domes on either end did not withstand Allied bombing during WW II and were rebuilt as simple pyramids after the war.

These four views show various aspects of Tōkyō Station, when opened. In the top left image, the building itself is visible to the left showing a train departure. Details of the elevated platforms are shown in the top right image. The two bottom views show respectively the waiting room reserved for the Crown Prince and Princes of the Blood and a suite in the Tōkyō Station Hotel.

The new central station, Tōkyō Station as it would eventually come to be known, the crown jewel of the Meiji railway system, was also its final capstone. Tatsuno Kingo had reworked the station’s design, and his plans called for massive and stolidly late-Victorian structure that was thoroughly Western in appearance with its bulbous octagonal domes;1 yet unabashedly Meiji in spirit. It was sited in Maronouchi, a location that had been proposed as part of the ambitious urban re-design scheme for Tōkyō undertaken by Ende-Boeckmann starting in the late 1880s. The edifice would not have looked out of place in Amsterdam, Antwerp, Hamburg, Copenhagen or in any large Northern European city on the Continent. When Balzer was replaced by Tatsuno in 1903, his design for the Japanese Revival style station withered. The IJGR management, encouraged by Gōtō Shimpei, decided upon a more grandiose station. Tatsuno’s design continued the style he had employed in his Manseibashi Station that stood in Tōkyō’s Kanda district, but it was grandly expanded: the station was made large enough to include a hotel, three restaurants, a post office, and of course there were three special waiting rooms, one for dignitaries and nobles, one for the Crown Prince, and one for the Emperor. Preliminary construction had commenced in 1908, final approval for Tatsuno’s plan was obtained in 1910, and the station was not completed until 1914, with opening ceremonies held on December 18th. The event was of such import that, at a time by which even in Japan railway inaugurations had become routine, the Prime Minister, none other than Ōkuma Shigenobu who had negotiated the building of the first railway line 1869 with Itō, Sawa, Parkes, and Lay, agreed to officiate. It was both fortuitous and serendipitous that the inauguration was dedicated by one of the few surviving from the handful of men who had been instrumental in the initial decision to introduce railway technology to the realm. In short order too, a larger-than-life statue of Inoue Masaru would be erected in the station forecourt as a memorial to the man even then known as the Father of Japanese Railways. The line beyond to Ueno wouldn’t be completed until 1925, after the Great Kantō Earthquake in 1923 had leveled some of the improved land, rendering right-of-way acquisition less costly.

Upon dedication of new Tōkyō Station, Shimbashi Station, where so much Meiji-era history had played out, where a young and hitherto sheltered teenage Emperor in silk robes of ancient pattern had publicly inaugurated the railway system, where a perspiring Ulysses S. Grant on one hot, sultry July night in 1878 had been chased down a corridor by a crowd of small girls who were daughters of high officials, was cornered, and “took each little hand and smiled upon them,”2 through which a young naval officer passed on his way back to ship after having a Japanese dragon tattooed on his arm during his “shore leave” many years before he assumed the throne of the United Kingdom as King George V, where the entourages surrounding the state visits of King Kalakaua of Hawaii, Crown Prince Yi Eun of Korea, Prince Henry of Germany, Prince Arthur of Connaught (bearing the Order of the Garter for the Emperor as a token of esteem on behalf of his uncle King Edward VII), the Duke of Genoa, nephew of the king of Italy all had passed, where the arrivals and departures of virtually every Japanese subject of any note, from the relatively modest to each and every Prime Minister, including the legendary Iwakura Tomomi, Itō Hirobumi, and Ōkuma Shigenobu had been witnessed, through which had passed a host of lesser luminaries such as Natsume Soseki, Rudyard Kipling, Isabella Bird, Lafcadio Hearn, and Ernest Fenollosa, would fall silent and be converted into a freight yard; its name changed to Shiodome.

As the Meiji era was ending, plans had been made to expand Kyōto station. These two views make an interesting comparison by which to judge its growth from the earlier views around the date of opening. The view of the yards is looking westward, toward which the mainline departed on its way to Ōsaka.

It is an untidy happenstance of history that the new central station, although designed and begun in the Meiji reign, was not to be completed during the Emperor’s lifetime. Notwithstanding that fact, the station is every bit a Meiji edifice and stands fittingly today as the culmination of all the efforts in railway building that had been undertaken in the preceding 40 years.

In 1909 Inoue Masaru breezily characterized the breathtaking pace of Japan’s modernization using the metaphor that Japan had “virtually stepped into trains out of kago.” Of course, the actual process was not quite so effortless. Nevertheless, in the course of a mere forty years, Japan had made quite a successful transition from ox cart to steam car. The course of development of railways in Japan in many ways mirrors that of the nation as a whole during the Meiji reign. The initial period of foreign dominance and fumbling was emblematic of the government’s own relative weakness and uncertainty in the years immediately following the Restoration. The initial confusion in building the first lines were a reflection of the deep ambivalence in the country as to whether the experiment in adopting Western technology was worth the disruption to traditional Japanese ways or not. The give-and-take diplomacy that was played out between Sawa, Portman, and Parkes was indicative of the give-and-take that was occurring simultaneously within the ruling oligarchy as to which Western nation would best serve as a model for future development. The tumult of the Satsuma Rebellion was directly felt in the complete halt in railway development, while the exuberance of the second railway mania was a direct function of the exuberance that followed on the heels of the 1895 Sino-Japanese War victories. The vacillation of the early period concerning whether to adopt the policy of government monopoly of railway ownership or encouragement of private enterprise to build railways as the government’s model for railway development is not dissimilar to the political vacillation as to whether an oligarchy or popular constitutional democracy should serve as Japan’s model of government. The 1880s saw political and social modernization gradually reaching an ever-larger portion of the populace and more comprehensive integration of those new ways into Japanese society as a whole. The same decade also saw railway service reaching further into the social fabric to offer affordable travel to the masses and an integration of disparate lines into a national system. The upsurge in tourism and service improvements of the 1890s paralleled the upsurge in Japan’s status on the world stage in the same decade. All the turmoil of the Russo-Japanese War was to be observed likewise in railway operations and development during it’s course, and at its issue, the railways emerged with the military having ever more influence in matters of future development, as did the nation as a whole. Nationalization in 1906–1907 was symptomatic of the centralization of power entailed in the drift away from the goal of pluralism that was to become notable in the period. The mushrooming of light railways that occurred after liberalization under the 1910 Light Railway Law went hand-in-glove with the fact that the standard of living for the masses had considerably improved over the course of the preceding decade, creating more disposable income, fueling in turn a desire to use transportation faculties. Finally, the policy of domestic self-sufficiency in locomotive building is an obvious reflection of Japan’s emergence at the end of Meiji as a budding industrial power. Few would be able to find a better-suited microcosm more emblematic of the development of the Japanese nation as a whole during the Meiji reign.

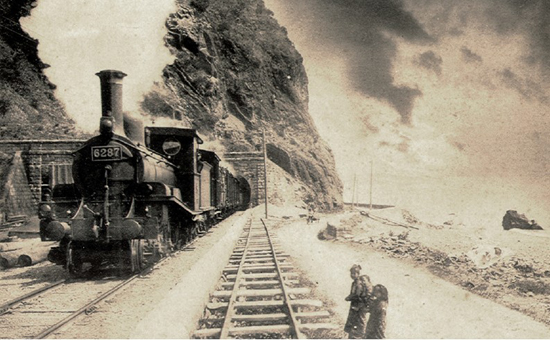

An unidentified coastal location, perhaps on the Atami line during construction, as presumably a contractor’s temporary narrow gauge (762mm) line is visible to the right while construction baulks and scaffolding are still visible at the curtained mouth of the new tunnel shaft just seen to the left of the smokebox door. The locomotive seen is a D9 class member, designated the 6270 class, a slight variation of the 6200 Class seen in an earlier photograph, but built by Dubs, soon to be the North British Locomotive Works. The running number on the smokebox door dates the photograph to after 1909 when IJGR changed its numbering scheme. Two small local girls, one with a babe on her back, watch the train lumber by while the driver keeps a lookout on the line ahead.

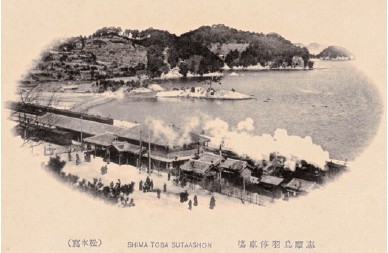

Toba Station was on the IJGR’s extension of the Sangu Railway that was added after nationalization. The station opened on July 21, 1911. This postcard affords a good view of the station, as an unidentified tender engine is set to depart with a passenger train.

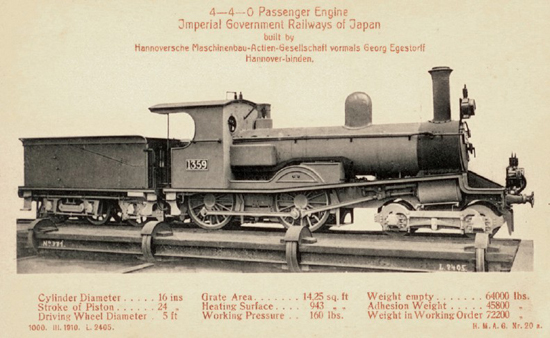

One of the more unique 4-4-0 classes is shown here in a builder’s card; the D9 or 6350 class that was introduced in 1909. Built by Hannover M. A. G., the class was a German build of the British 6270 class of 1900, from blueprints probably provided either by Dubs or by the IJGR at a time when Dubs order books were likely full. They were the only German 4-4-0s ever to run in Japan. The most obvious difference when compared to the 6270 class was the “1+truck” tender, however there were other slight variations. The small, low-pitched boiler of this class gave it a distinctly old-fashioned appearance. Even the progenitor 6270 class had been ordered at a time when the benefits of large boilers were becoming widely understood in the engineering world. By the time this class was ordered almost a decade later, there was little reason to retain a small boiler design. With what was fast becoming relatively small cylinder dimensions of 16” dia. x 24” stroke and five-foot drivers, the class had a distinctly retrogressive air for its day. In hindsight, it could be said to represent a missed opportunity for a bolder order to more modern design specifications. The class consisted of 36 members. As these Hannomag locomotives were ordered just before the 1909 renumbering, they received an 1891 numbering scheme class designation of D9. This example bears an 1891 scheme running number on what is somewhat similar to the standard style number plates introduced with the 1909 scheme.

The first section of the Chugoku Tetsudō (lit. “Midland Railway”) was commenced from the San’yo mainline at Okayama in 1898; ambitiously bound northward for Yonago on the Sea of Japan Coast. The mainline never made it beyond Tsuyama. However, the company did complete another segment westward from Okayama in 1904 to the town of Tatai, giving it a system shaped like a backwards letter “L.” The entire system (including its sole branch of one mile to Inariyama) barely exceeded 50 miles. The Chugoku started with 8 locomotives from Nasmyth Wilson: 5 versions of the popular A8 class 2-4-2T and 3 beautiful little 0-6-0 tank locomotives, identical to the IJGR 1220 class. By 1910 the line had prospered enough to afford to increase its roster of 8 locomotives by one, and the 2-6-2T prairie tank locomotive shown here was that single addition, bearing running number 10. Although built in Germany by Hannover, its general design is obviously inspired by the numerous Schenectady and Baldwin 2-6-2T locomotives that were very popular in Japan at the time. This diminutive Prairie tank would remain the largest locomotive on the Chugoku for the remainder of the Meiji reign. Paradoxically, while this locomotive was equipped with the venerable Stephenson’s valve gear, the smallest locomotives on the line, the tiny 0-6-0Ts, were fitted with the more modern Walschaert’s valve gear.

The Emperor’s son Yoshihito ascended to the Chrysanthemum Throne as the Taishō Emperor, reigning over a nation that had become the most powerful independent nation in Asia, was to gain wide acceptance as a world power within a decade, and possessed a railway system that, but for the narrowness of its gauge and preponderance of single track lines, could be compared on fair terms with many of the busiest, most profitable such systems in the world.

As the Meiji era drew to a close, train ridership was increasing, as were train lengths and train weight. This photo of an express train negotiating the Hakone Pass shows one of the German-built express locomotives handling an express with the assistance of a banking locomotive at the rear of the train. The train length is now ten carriages, the last three of which are first class vehicles, as evidenced by the white stripe just visible at the rear of the train in front of the helper engine.

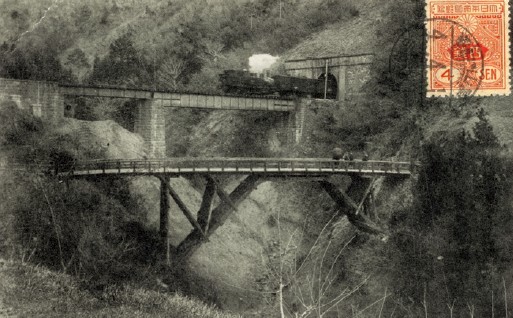

A very scenic late Meiji/early Taishō view of a freight train, piloted by what appears to be a B6 class locomotive at a tunnel at an unidentified location being watched from the bridge of a roadway by the locals. Note that while the railway bridge is of masonry and steel, the local roadway passes the ravine over a wooden bridge.

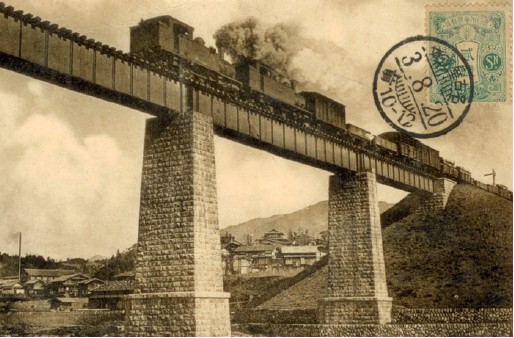

Freight tonnage per train also increased at the end of the Meiji reign, and if larger locomotives equal to the task were unavailable, motive power departments coped with heavier trains by using the practice known as doubleheading. This late Meiji/early Taishō view (postmarked August 20, 1914) shows tandem B6 locomotives running bunker first at the head of a long freight, with a cattle car fourth from the front derived from British design practice. Assuming that both locomotives had been coaled with the same coal at the engine shed and were in comparable states of repair, the fireman in the second locomotive must have been more skillful in his art, as the first engine’s exhaust is much sootier with particulate matter: evidence of incomplete combustion.

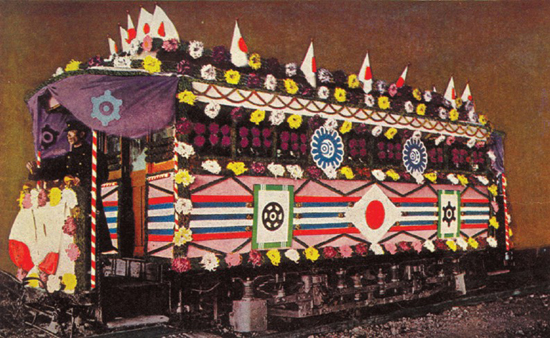

During the Meiji era, Japan’s municipal trolley lines established a widespread practice of decorating their trams to mark special occasions, both festive and solemn, and happily for lovers of crêpe paper and swag, developed that tradition with unabashed glee. The custom was observed by municipal transit lines on a scale and depth unmatched in either Europe or the Americas, adopting the Victorian Western cultural phenomenon of ceremonial motive power decoration and transforming it into something that was to become quintessentially Japanese. This posed photograph records one of the Tōkyō Municipal Railway’s tramcars, with both versions of the corporate shamon prominently displayed, as decorated in commemoration of the Shinto ceremonies installing the Meiji Emperor in the Shinto Pantheon, which occurred in 1920. As such, it was almost certainly the last Meiji-related railway event to have occurred in the realm. Note the driver posed in his great coat beneath the drapery of imperial purple. The two blue Kiku-no-gomon badges seen over the windows bear the ideographs of a sun surrounded by a crescent moon, which combine to form the kanji “Mei-” of Meiji. The tradition of specially decorating municipal trams can still occasionally be seen on the surviving streetcar lines in present-day Japan. Although the practice has become less prevalent with the gradual replacement of most such lines by subways, Japan is still arguably the best place in the world to observe this near-extinct cultural tradition, directly descended from Victorian times.

Tōkyō station at night, showing the effects of modernization brought by electric power, with a new motor-car taxi that was destined eventually to replace the venerable jinrikisha in the foreground.