PROLOGUE

Japan Before 1853

Prior to 1543, the only contact between Japan and the Western World was indirect, via second-hand sources, such as the reports of Marco Polo, who relayed what he had learned of those islands from hearsay during his sojourn in China at the court of Kublai Khan. Polo used the name Gipangu, from which we derive Japan. Gipangu is itself an Italicized version of the Chinese pronunciation Jih-pōn, which had been settled upon as the term used in communications between the two respective Emperors of Japan and China. The Chinese characters Jih-pōn 日本 mean respectively sun and origins, as from the ancient point of view it was the easternmost known land in the world: the land where the sun rises. The ancient Japanese called their land Yamato, but when they adopted the Chinese writing system for their spoken language (the two languages are otherwise unrelated) in the 3rd century BCE, they began to use the same two written characters they had adopted for the name of their country in the diplomatic correspondence between the two Emperors. But they pronounced those two characters using native Japanese words. As the word for 日 sun is pronounced ni in Japanese and 本 origins is pronounced hon or pon, they eventually came to call their land Nippon or Nihon. The Japanese may have settled Yamato, but so far as concerns the rest of the world, the Chinese pronunciation was the one by which it became known. As a result of the way their writing system developed, the Japanese can pronounce any Chinese-derived ideograph, to this day, in two ways: the “Chinese style” pronunciation or the native Japanese. Thus 山 (mountain) can be pronounced in Japanese using the Chinese pronunciation San or the Japanese pronunciation Yama. Westerners are most familiar with this from references to Fuji-yama and Fuji-san.

Travel in Japan changed little during the millennium stretching from the 8th Century to the 19th Century when Japan made the decision to modernize. In the 8th Century, Buddhist monks, most notably the legendary monk Gyoki, instituted Japan’s first notable public works program, developing a system of communication with new roads, canals, and bridges to enable public access to the great temples of the day. In that century as well, the first system of post stations and inns (restricted to the use of only government officials) were established, being staged approximately 30 ri (about 75 miles)1 apart. Transportation technology was little improved over the course of centuries intervening between the age of the engineer-monk Gyoki and the 19th Century. The distance between stages had been reduced to anywhere from four to ten miles, but as road building and road maintenance were the responsibility of the village or locale through which they ran, there was a great variance in traveling conditions throughout the realm. Travel was either on foot or horseback, by ox-cart (for nobility) or palanquin, a type of sedan chair known in Japanese as kagō or koshi, depending on its configuration.

The average load for a packhorse was 250–350 pounds. Under the best conditions, a traveler could travel 25 miles in a day; usually however, the average was around 18. This continued to be the average rate of travel up until the 1870s. Rivers formed a natural highway network for travel along so much of their length as was navigable, but interposed barriers to travel routes that crossed their courses. At some rivers, it took travelers up to half a day simply to accomplish a crossing. Because some rivers, such as the Ōigawa, formed domain boundaries, boats of any kind were forbidden on them as a defensive measure, necessitating detours of many miles in a route to a point where they could be forded. (The well-to-do would hire kataguruma, coolies stripped to a fundoshi, to carry them on their backs across at this point.) Many rivers were unbridged simply because bridging strong enough to withstand the severe seasonal flooding so prevalent among Japanese rivers could not be devised. Due to the relative lack of bridging, a scattered flotilla of small craft not much larger than a typical rowboat flourished at the various permissible crossing points and served as ferries between the shores. Even on the major roads, there were frequent gates, meant to keep the peasants of one fief from traveling freely to the next. Due to the fact that Japan is an archipelago, there was naturally a great emphasis in coastal shipping, but because of shipping restrictions, the largest ships (the Sengokubune) were by law limited to a burthen of 1,000 koku (a unit of measure defined as the amount of rice necessary to feed one person for one year: approximately 5 bushels), although by the first half of the 19th century the law was not as strictly enforced and some ships of larger burthen had come into service.

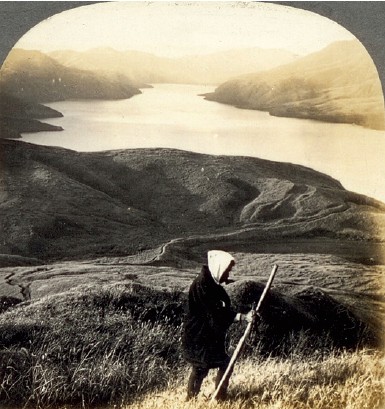

This view of Lake Ashino near Mt. Hakone shows what was by far the most common mode of travel in Japan from ancient times well into the 1890s. Few but the relatively well-off could afford to travel on anything but foot even into the 1870s in Japan.

For centuries, the more fortunate in Japan could travel in a kagō, a sort of sedan chair as is shown here. While the Japanese became quite accustomed to it over the course of centuries of use, the first Westerners in Japan could not acclimate themselves to the cramped position of being seated cross-legged for long hours of slow travel.

The year 1543, a mere 21 years after Magellan’s crew had completed the first successful recorded circumnavigation of the world, marks the first recorded direct contact between Japan and Western civilization, in the form of three Portuguese sailor-adventurers, Fernão Mendez Pinto, Christopho Borrello, and Diego Zeimoto. Pinto left a chronicle of his voyage that reads like the script of an action-adventure film. According to Pinto, by a long chain of events, the three found themselves stranded on an island where Portuguese ships rarely put in, believed to have been located somewhere near present-day Macao. After weeks of waiting for a ship to call in port to no avail, the Portuguese were beginning to despair when a squadron of pirates (probably Chinese) sailed into port and dropped anchor. As the appearance of other ships was unlikely for quite some time, the three agreed to enlist as sailors with the pirates, hoping to work their way along their route, as part of the crew, until the pirates would reach Malacca (what is now the area of Singapore), the straits of which were a strategic bottleneck for shipping through which ships from the Far East bound for Europe would have to pass, where the three could take their leave and find passage home. The three set off with the pirates in a squadron of junks only to be attacked at sea by a rival pirate band. Although the junk on which the three were in service escaped pursuit, the sails of their junk had been damaged during the battle such that it lacked full sailing capacity and was thereafter blown off course during a storm that followed the battle. In an attempt to find the closest friendly land where they could repair their ship without fear of apprehension by the Chinese authorities, the pirates attempted to sail to the Okinawan Islands, but spotted land fortuitously and took safe harbor at the small island of Tanegashima, in southern Japan off the coast of Kyūshū, the southernmost of Japan’s four major islands.

Although this view was obviously taken after the introduction of photography in Japan, there is little to distinquish it from a scene centuries earlier. A typical example of one of the ferries that existed in Japan by the tens of thousands is seen with a full host of passengers. Boats such as these were the typical short-haul ferries of Japan well into the years of the Meiji reign.

With the introduction of Western breeding stock beginning in the 1860s, the horse population of Japan gradually grew. Native Japanese horses (such as seen at left) were closer to the Western pony and were notoriously bad-tempered. By the 1870s, a series of relay houses had been established in Japan, where theoretically a horse could be rented for the road ahead to the next post station. This was initially a very unreliable service. Shown here is what a Western traveler weary from a day’s travel on foot would have gladly paid premium price for in the 1870s: two pack horses (one on which to ride with baggage, and the other for baggage and accompanying guide) available for hire at the post house.

Japanese ship design changed little in the three centuries between the visit of the first Western sailors to Tanegashima in 1543 and the opening of Japan by Matthew Calbraith Perry in 1853. Shown in this 19th century woodcut is a fairly representative version of one of the largest Japanese ships that would have been seen in the centuries that preceded the modernization introduced in the Meiji era.

By coincidence of history, these three Portuguese came ashore in Japan at a time when the realm was in political turmoil. Since as early as 1192 at the conclusion of the decisive Taira-Minamoto Civil War, it had been established political custom in Japan that the Emperor (the Tennō or, as the Victorians liked to called him, the Mikado) was a figurehead sovereign who, to borrow the common axiom, “reigned, but didn’t rule.” True political and military power was vested in a nobleman or daimyō holding what by force of arms and custom had become the hereditary title of Seii Tai Shōgun, or “Barbarian-quelling Supreme Commander.” Shōguns (as they came to be called) and their dynasties, the Shōgunates, came and went in typical feudal fashion: rebellion and overthrow by force at critical moments, but always the institution of the Imperial Dynasty had been maintained. Unlike neighboring China’s changing dynasties, new Shōgunal dynasties never took the title of Emperor, but were content to keep the Emperor in place with titular powers and assume the title of Shōgun. The only fundamental question at the fall of any Shōgunal dynasty was which influential daimyō would capture the title of Shōgun for himself and his descendants. In the early 1540s, those first Portuguese mariners sailed unknowingly into just such a situation.

By this date, the Ashikaga or “Muromachi” Shōgunate, in place since 1333, had lost political and military control of the country and had largely collapsed by the end of the Ōnin Wars in 1477. A scramble for the title of Shōgun had been festering in the land ever since—a period of intermittent civil wars between jockeying daimyō to determine who would succeed as Shōgun now known as the Sengoku period. By stroke of good fortune for those first three Portuguese, the hold of the pirate junk was stocked with plunder, which the pirates starting trading with the locals, so the ships stayed in port for a few weeks, and were visited by the local daimyō, who was amazed to find three men with beards and faces the likes of which he had never before seen and who aroused a great curiosity in him. The pirates had plenty with which to busy themselves in their ship repairs and setting up a smuggler’s bazaar at which to haggle over the prices to be gained from their booty, but the three Portuguese were at loose ends until the voyage resumed, and contented themselves to play tourist and go hunting with their trusty arquebuses. In Japan at that time, firearms and firearm technology were virtually unknown. Diego Zeimoto was a particularly good shot, and bagged twenty-six fowl in one day with his arquebus, much to the amazement of the locals as he returned to town. News traveled quickly to the local daimyō, who requested a demonstration. The daimyō was so impressed that he accorded Zeimoto unusually great honors and was exceedingly eager to acquire firearms and to adopt the new technology. The desirability of such technology in times such as Japan was then experiencing is self-evident. By the time the pirate junk weighed anchor and set sail, the three Portuguese on board had come to the realization that here was a market ripe for exploitation. They lost no time in promoting the idea on their return to Lisbon.

A brisk but intermittent trade gradually developed as quickly as ships of the day could sail. Within three years, the first Portuguese vessel had come to Kyūshū (remarkably fast contact given the rate of change and travel in those ages). By 1549, Francis Xavier had established a mission in Kyūshū and the Portuguese were attempting to be the first Western nation to forge regularized trade relations with Japan. The first cannon were purchased and brought ashore two years later. The Portuguese found one of the bays at the base of a long cape in western Kyūshū to have a natural harbor well suited for a port, and requested permission of the local daimyō to anchor there, which was agreeable. The locals had named the small fishing village situated at the anchorage “Long Cape” (Naga-saki in Japanese). By 1571, the first regular trade ships from Portugal anchored in its waters and Nagasaki was on its way to becoming a trade center. The local daimyō were quick to send their best swordsmiths to learn gunsmithing from the Portuguese and to establish manufactories at the local arsenals that each domain was required to maintain as a part of its national defense obligations. Firearms proliferated rapidly from that small foothold in Kyūshū, and within years the use of firearms had spread throughout the realm. Henceforth, the transfer of Western technology to Japan would become a notable aspect of Japan’s interaction with Western civilization: small initially, but accelerating at an amazing pace during the Meiji period.

The Portuguese were only too happy to provide firearms to the local daimyō and teach them gunsmithing in exchange for the products of technologies understood in Japan that the West had not at that point mastered (such as lacquer ware) which naturally would be in higher demand and produce a higher profit margin. Later, after an abortive invasion of Korea in the 1590s, Korean potters were brought back to Kyūshū bearing new technological knowledge and skills that proved instrumental in making improvements to the local earthenware industries. They brought with them the secret that kaolin was necessary to manufacture porcelain (a technology that Europe wasn’t able to duplicate until the eighteenth century), and the skills to fire it. The discovery of suitable kaolin deposits in Kyūshū soon resulted in the first Japanese porcelain kiln located at Arita, a name ever after synonymous with porcelain in Japan. Arita ware was quickly added to the holds of Portuguese caravels as a trade commodity. By that time the Portuguese had also learned that there was a ready market in Japan for an agricultural product discovered in the newly found western hemisphere called tobacco. Technology and tobacco, canons and cannons may have seemed promising enough to insure future commercial success to the Portuguese. But matters were not that simple. Because of the mere coincidence of having first landed in Kyūshū, the Portuguese trade and missionary pursuits were centered there. They were on good terms with the local daimyō, the powerful Shimazu clan of Satsuma, and Portuguese influence grew locally as many of the populace, and indeed certain daimyō were converted to Christianity. Unfortunately for the Portuguese, the Shimazu had taken a position antagonistic to the formidable Toyotomi Hideyoshi.2

By the closing years of the 16th century, the political-military contenders for the title of Shōgun had reduced down to only a few, of which Hideyoshi was one. Hideyoshi eventually gained the upper hand in the Sengoku struggles (it was he who was responsible for the ill-fated Korean invasion so felicitous to Japan’s porcelain industry), and by the time he landed in Kyūshū to deal a blow to the Shizamu clan, was near the height of his power. Naturally, the Shimazu used all the resources available to them, among which were the Portuguese; specifically their firearms and the cannon on any of the Portuguese ships that happened to be in port and available to render a service to friends in need. The Age of the Conquistador was then in full flower, and the Portuguese were too tempted to emulate the successes of their Spanish cousins. Of course, Hideyoshi viewed this as what we would today label foreign intervention, was not at all pleased by the unwelcome complications Portuguese fire-power had injected into his campaign against the Shimazu clan, and viewed everything about the Portuguese, from ships to cannon to religion, as a potential threat to his power base. He was one of the samurai who had served under Oda Nobunaga at the Battle of Nagashino in 1575. Nagashino is said by some to have been the world’s first use of rapid-volley firing on a large-scale basis by roughly 1,000 musketeers firing en masse; a tactic pioneered by Nobunaga. It is said to have preceded European use of this tactic by some 25 years and was instrumental in victory. Hideyoshi knew first-hand the effectiveness of this new Western technology and feared it. He prevailed in his campaign against the Shimazu, and one of the outcomes of his victory was the issuance of edicts putting foreign trade (and with it, foreign ideas) under centralized control, as his observation of the growing Portuguese power and influence while he was in Kyūshū convinced him that it was a danger to political stability. Hideyoshi’s former mentor Oda Nobunaga had experienced problems with religious groups and had started the process of issuing edicts regulating them: Hideyoshi followed his former leader’s policies. His edicts at first tended to be circumvented or ignored, but as his power grew, were ultimately heeded. For good measure, Hideyoshi outlawed the wearing of swords by anyone except members of the samurai class and barred their possession with his celebrated Katanagari (“Search for Swords”) purge of 1588, which required that firearms too be surrendered—a means of weakening the ability for armed resistance and curtailing the spread of firearm technology in hopes that Nagashinos and Shizamu campaigns would never happen again, or at least that future clashes would not be complicated by firearms.

Hideyoshi died in 1598 leaving a five-year-old son, Hideyori, as his heir, with several of his most loyal vassals charged with Hideyori’s protection. One of those vassals, however, saw an opportunity in the power vacuum created by the untimely demise of Hideyoshi and moved quickly to usurp his former master’s position. Although he was relatively modestly born, Hideyoshi’s former ally and subordinate not only possessed tact, acumen, and military prowess, but equally importantly a great deal of luck and good sense of timing. He was named Tokugawa Ieyasu, and he succeeded in seizing power from the defenders of the young boy he was pledged to protect and in building on Hideyoshi’s achievements before Hideyoshi’s enemies could undo them. Naturally there were more battles, but Ieyasu effectively settled matters, re-unifying Japan in 1600 at the decisive battle of Sekigahara, a name that rings in the ears of the Japanese much as Hastings does to an Englishman, Poitiers to a Frenchman, or Gettysburg to an American. Ieyasu’s legacy was the Tokugawa Shōgunate, lasting from 1603 to 1868.

Although this photograph was probably taken in the 1890s, most of the ships seen in this photograph are of the type traditionally seen in Japan for centuries. More modern steamships would gradually appear in Japanese ports after the decision was made to modernize. The location is Ōsaka.

Ieyasu was a bold, capable, and cunning field commander, but he was not the model of a progressive political leader. On his accession to the title of Shōgun, Ieyasu put Japan on a thoroughly traditional and sedentary political course. He left the Emperor undisturbed to reign at the capital in Kyōto and established his Shōgunal capital within his domain at a small provincial castle town known as Edō (sometimes written Iedo, Yedo, or Jeddo, as Western scholars had yet to arrive at a standardized system of transliteration of the Japanese language) which centuries later, at the end of the dynasty he founded, grew to be the most populous city in the realm. Ieyasu too was present at Nagashino and undoubtedly he remembered vividly the trouble firearms had caused Hideyoshi, with whom he had been then allied, in the Shimazu campaign. He undoubtedly shared with Hideyoshi the view that the adventurism the Portuguese had demonstrated was a threat to political stability in Japan, and by extension, to his rule. Being all too cognizant of the challenges that can arise when a unifier like Hideyoshi passes from the scene, and undoubtedly wishing to avoid similar consequences for his successors, he reigned as Shōgun for only some three years and thereafter made a point of “retiring” in favor of his son Hidetada, using the rest of his days as a power behind the throne in order to assist and prepare his son for continuation of the dynasty, while acclimating the rest of the country to the notion that Hidetada was their ruler. To Ieyasu, the notion of contact and trade with Europe was still largely an unknown element with an exceedingly bad track record at that point; not to be highly regarded based on his past experience. By this point in time, the Dutch had found their way to Japan in the form of the Dutch East India Company, as had a sole Englishman in Dutch employ by the name of Will Adams, who in fact served informally as an advisor to Ieyasu. By 1611, through Hidetada, Ieyasu had granted his first audience to a Spanish envoy and by 1613 to an envoy from King James I of the political entity that just eight years earlier had become known as Great Britain. As a result of these missions both nations were permitted to establish trade relations. The English thereupon established a porcelain factory in the Kyūshū town of Hirado. The Spanish and English relations must have been nothing more than a provisional experiment in the minds of Ieyasu and his son Hidetada. Ieyasu was by then an old man approaching the end of his life and was acutely aware of the need to solidify and legitimize his régime, the power of which was subject to challenge by virtue of its newness if for no other reason. Among his last acts, through Hidetada, Ieyasu, apparently disapproving of the course foreign trade was taking, moved to rein in what he perceived as growing Western influence and put in place prohibitory edicts in 1612 and 1614. In 1615, Toyotomi Hideyori, the son of Ieyasu’s former master, challenged him one last time in battle, was defeated, and was forced to commit suicide leaving no heir. With that defeat, all effective opposition vanished. Ieyasu could breathe a sigh of relief. A year later, in 1616, he died—the same year that saw William Shakespeare pass from the world scene.

Careful to pursue the course of further consolidation of the new régime’s power, which was still at best untested and at worse tentative, Hidetada and his son, Iemitsu, lost no time following the great Ieyasu’s lead with edicts designed further to reduce Western influence; restricting all foreign ships and trade to the two Kyūshū ports of Hirado and Nagasaki in 1616 (still later only to Nagasaki) and prohibiting Spanish trade outright in 1622–1624 (the Spanish experiment had proven troublesome—problems again with religion and the Conquistador Mentality). By this time, the English trade venture only recently established in Hirado had closed as it was not commercially viable. With further edicts in 1635 and 1636, all Japanese were prohibited from foreign travel and all Japanese who found themselves abroad were deemed exiled and forever barred from returning home. It was decreed illegal for any Japanese to own a ship with more than a single mast or exceeding fifty tons displacement, effectively an outright ban on ownership of ocean-going vessels.

As restrictions against Western influence mounted, those local Japanese in Kyūshū who had converted to Christianity bore some of the burden and became resentful. In 1637 an ill-fated Christian revolt, the Shimabara Rebellion, broke out near Nagasaki, aided in part by the Portuguese. The locals again resorted to Portuguese firearms, long since banished under the Katanagari, which further convinced the new regime that foreign influence and technology were a threat. As a result, in 1639 the Portuguese (along with their meddlesome missionaries and gunrunners) were outright barred from entry anywhere in Japan. The remaining Dutch East India Company, which kept strictly to business and did not import religion, fared better, but was no longer allowed to freely occupy sites in the Nagasaki environs. Starting around 1641, the number of Dutch ships were curtailed and severely controlled, only being allowed to anchor in port at certain periods, not allowed to come and go freely, and all Dutch trading entrepôts, factories, and residences were required to be moved and thereafter confined to a small island just off shore in Nagasaki harbor called the Deshima that was ordered to be enlarged artificially to the size of about one hectare. Housing, warehouses, and other necessary buildings for the conduct of trade were built there, the entire island surrounded by a high fence, and a bridge was built that connected it to the town proper, with a guard post manned by the local police and gates that were barred year-round. The Dutch traders were not allowed to leave the island, except the Opperhoofd (“chief,” lit. Overhead) of the trading post who was required to make a yearly report to the Shōgun in Edo called a Fusetsu-sho, and was allowed to leave the Deshima for this purpose. Otherwise the Dutch might as well have been politely treated hostages. No Japanese men were allowed on the island unless they were employees of the company. No Japanese women were allowed at all, unless they were courtesans. The trade ships were allowed to arrive in summer, usually July, and were required to turn over their sails, arms, and ammunition to the local authorities to prevent any adventurism during their stay. Any Dutch ships in port were required to leave by no later than the end of September; even delay caused by the worst of sailing weather being unacceptable. As the time approached, their sails, arms and ammunition would be returned, the ships would be refitted, provisioned, and loaded with a year’s accumulation of stock in trade, and when all was well, set sail.

There must have been a very lonely and desolate feeling on the tiny islet each October, when the last Dutch ships had left and the Opperhoofd and the ten or twenty Dutch resident employees who remained in isolation set about preparing for winter and the return of Dutch ships the next summer. But the pattern had been set. Like a larger Deshima whose last ships had sailed, for the next two hundred years Japan settled into a period of profound isolation.

Hiroshige, one of Japan’s masters of the woodblock print, created this scene titled Evening at Takanawa, one of the finest works of his series Tōto Meisho, probably around 1840. The scene is a classic depiction of the methods of transport available in Japan before the introduction of Western technologies and shows a representative sampling of the kinds of traffic to be encountered on the Tokaidō, Japan’s largest and busiest highway at the time. An ox-cart, kagō, ships, and pedestrian traffic are all seen in the vicinity of a local tea-house at the side of the pre-Meiji era’s premier super-highway, where the hostess is greeting pedestrian wayfarers. Note the Japanese custom of riding atop of a rented packhorse, along with one’s baggage. Roughly three decades after the scene depicted in this print was drawn, Takanawa would be the focal point of a struggle between the new government and reactionary elements in the Japanese military, who were obstructing building of the first railway in Japan. Eventually, the ageless calm of evenings at Takanawa such as the one shown here would be interrupted by the high-pitched shriek of British-made steam whistles and the sounds of occasionally passing trains.