6

WHEN TURN-ONS TURN AGAINST YOU

Erotic scripts can wreak havoc by drawing you into unworkable repetitions.

The more you understand the erotic mind, the more obvious it becomes that the same depth and complexity that makes eroticism so fascinating and rewarding also guarantees that a great deal can go wrong. You know this fundamental principle of erotic life: anything that intensifies passion can also disrupt it. From the erotic equation you know that the opposite is equally true: anything that inhibits arousal can also enhance it. This means that virtually any thought, feeling, or set of circumstances can be either an aphrodisiac or an antiaphrodisiac.

In Part I you used peak experiences and fantasies as tools of self-discovery. Now in Part II you can apply your discoveries to the recognition and understanding of a variety of common erotic problems, some of which you may not have considered before. Like a lot of people, you might be reluctant to think very much about these unwelcome annoyances. They are deeply unsettling, and many people are superstitious that focusing attention on these problems will somehow make them worse.

Some people are uneasy because they have a vague awareness that their erotic patterns are troubling them but are hesitant to look too closely, especially if they’re not sure what’s wrong. If you sense such a reluctance within yourself, I assure you that grappling with erotic concerns directly—naming them, exploring their shape and texture, even when it’s disturbing to do so—is the only effective way to resolve them. Long-term improvements are the rewards for short-term discomfort.

I’m absolutely convinced that if you take the time to understand erotic problems—even ones that don’t affect you personally—you’ll be surprised at how your appreciation of the erotic mind deepens. Eroticism is so intricately involved in the rough-and-tumble of living and loving that messy conflicts and difficulties are as unavoidable in the erotic realm as in life in general. As you know, those who expect life to be problem-free usually end up disappointed and demoralized. Healthy eroticism does not avoid problems; it works with and transforms them.

The erotic problems we’ll be looking at are qualitatively different from those sex therapists have traditionally talked about. Ever since Masters and Johnson launched modern sex therapy in the late 1960s, the focus has been mostly on physiological function and dysfunction, especially two observable and measurable events: arousal (a man’s erection or a woman’s vaginal lubrication) and orgasm (reliably having one or more, but not “too fast” or “too slow”). As a result of this emphasis, most people assume that if the “equipment” is functioning properly everything else will pretty much take care of itself.

Sex therapy has grown, and, as with all new fields, its range of inquiry has expanded. For example, many of today’s clients are concerned about a declining or absent urge for sex, traditionally called sex drive, libido, or horniness—now referred to simply as desire.1 Neither measurable nor directly observable, desire is a totally subjective state combining biochemical influences, memories of past sex, visualizations of future possibilities, and a predilection for attending to and interpreting everyday events in an erotic way. To study desire we must move beyond our preoccupation with sex organs and venture into more elusive territory where even the most sophisticated laboratory instruments become practically useless.

In this chapter I want to call your attention to three types of erotic problems that frequently bring people into therapy. First, we’ll see how some of the same emotions that intensify arousal can also produce unwanted side effects that inhibit our desire or disrupt our capacities for arousal or orgasm. Second, we’ll consider how troublesome attractions can draw us toward partners who are destined to disappoint or hurt us. Third, we’ll discover how love-lust conflicts sometimes make it difficult or impossible to experience affection and passion with the same person. These problems all contain a similar paradox in which long-standing and compelling turn-ons turn out to be antithetical to satisfaction.

As we’ve explored the dynamics of passion throughout Part I, I’ve given special attention to peak turn-ons anonymously described by The Group in the Sexual Excitement Survey, while encouraging you to examine your own. Although I’ve drawn extensively on my experience as a therapist, I believe it is crucial that our ideas about the erotic mind be based on a solid understanding of nonproblematic eroticism.

Now that we’re turning our attention to troublesome turn-ons, you’ll be meeting many more of the individuals and couples who have come to me for therapy. Most of what I’ve discovered about erotic problems and their solutions has been with the help of my clients.2 In this chapter and the next, you’ll see how a variety of people have used therapy to understand and unravel their erotic dilemmas.

As the evolution and meaning of these difficulties becomes clear, you might feel a bit frustrated when solutions aren’t immediately forthcoming. Rest assured that in Chapter 8, “Winds of Change,” I will describe a seven-step program that anyone can use to help with erotic problems. There you’ll revisit the same clients whose quandaries you’ve encountered in the preceding chapters. And you’ll see how they used their insights to forge new pathways to sexual healing and growth.

FEELING SIDE EFFECTS

As you know, emotions play a crucial role in virtually all memorable encounters and fantasies. The unexpected aphrodisiacs—anxiety, guilt, and anger—often have a particularly strong association with the risks and conflicts that animate so many popular erotic scenarios. Normally, these emotions cause us few if any problems because our erotic minds use them sparingly and subtly. We also employ safety factors—such as the knowledge that there is no real danger or that we are capable of handling it—to increase our comfort level.

Imagine yourself beginning a passionate encounter with your lover on the living room sofa when you notice that you forgot to close the draperies, and a nosy neighbor could be spying on you from a darkened window across the street—probably not, but how can you be sure? The idea of an unseen observer being titillated or scandalized triggers in you an exciting undercurrent of nervous uncertainty or naughty guilt. This slight nervousness enhances your arousal because you know you’re actually secure. After all, the lights are low and you’re not exactly parading in from of the window. No one can accuse you of being an exhibitionist. Besides, you’re feeling especially proud of your sexuality tonight, and you like the concept of turning on or shocking a prying prude.

Keep in mind, however, that all emotional aphrodisiacs are dual edged; they have the capacity either to boost or to disrupt arousal—depending on the situation and the individual. So while you might be stimulated by thoughts of being watched, your lover might feel self-conscious until absolute privacy is restored. What for you is an excitement-boosting hint of risk is for your partner a source of genuine worry about what the unseen neighbor might think—or worse yet what he might say to others. This episode has an easy solution; you can close the drapes or lower the lights even further and continue enjoying each other. Privately, however, you may retain the image of the voyeuristic neighbor in the back of your mind as an aphrodisiac.

In this section we are concerned with men and women for whom certain emotions have become so strong and central to their arousal that they are unable to shield themselves from their disruptive effects. Typically, these are people whose erotic development took place in atmospheres thick with anxiety and guilt. Over time their erotic minds learned to transmute these feelings into erotic fuel. They became so adept at using their emotions for excitation that they stopped noticing how frightened or guilty they really were. Perhaps without realizing it they came to require strong doses of guilt or anxiety to become highly aroused. Unfortunately, some eventually reach the point where the same feelings that have always turned them on begin disrupting their sexual functioning or inhibiting their desire.

Brian: Relaxation and arousal don’t mix

With great embarrassment Brian told me that about six months earlier he had “flunked out of sex therapy,” where he had been trying to solve a distressing problem. Unpredictably and without warning his penis would go limp when he was about to start intercourse. It didn’t seem to matter whether he was with Julia, his primary sex partner for almost three years, or any of the other women he sporadically dated. Although he had occasionally worried about his erections over the years, recently sex was becoming more worrisome than fun. And Julia was convinced that Brian was losing interest in her.

Their previous therapist had suggested that they work as a couple with some of sex therapy’s famous comfort-building exercises. In their first few home assignments they took turns stroking each other sensuously and affectionately, bypassing the genitals to avoid performance pressures. These massages went fairly well, although Brian was painfully aware that he was not getting aroused. Before long Brian began avoiding the exercises but couldn’t explain why. All he knew was that he felt completely nonsexual and was unshakably convinced that this approach couldn’t possibly work. His entire being was shouting a silent but resounding “no!” to the therapy.

Brian had heard me speaking about emotional aphrodisiacs at a conference and had a strong intuition that much of what I said applied to him. “Especially,” he told me over the phone, “the stuff about danger as a turn-on—that’s me all over.” We agreed to meet on a one-to-one basis and invite Julia to join us later, when and if that seemed appropriate. Like most people, Brian didn’t talk easily about the things that aroused him. Slowly, however, as he used his peak turn-ons as avenues for self-discovery, the dramatic themes that animated his inner erotic life became apparent.

He grew up in a small, traditional Midwestern town where most people knew what everyone else was doing. As a young boy he was extremely curious about girls’ bodies and was always coming up with games that allowed him to see and touch the “nasty places” that intrigued him so much. He never knew if a girl would be willing to play along, would get upset, or, worse yet, would tell on him. Worry was always a component of his sexy adventures.

Later, when a friend showed him how to masturbate, he became an enthusiast and soon also discovered the thrill of fantasies, most of which had a similar flavor of risky excitement. Meanwhile, opportunities to ‘explore his burgeoning sexual curiosity with real live girls were few and far between. One older girl who lived on a nearby farm was a welcome exception. He fondly remembered many hours of kissing and caressing in the hayloft.

With the exception of this one older girl, all his other encounters involved long, drawn-out seductions that were both exciting and totally nerve-wracking. His strongest recollections were of trying to conceal his trembling knees and clammy hands. In short, anxiety had always been intricately interwoven with his eroticism; to be aroused was to be anxious.

When he left for college in a larger city, sexual opportunities were more plentiful, yet he continued to gravitate toward women who seemed reticent. With each new partner he devised clever ways to reenact the anxious anticipations that so consistently stimulated him, such as initiating sex in semipublic places or convincing his partners to try things they hadn’t done before—anal sex or three-ways with other women, for example. When he wasn’t proposing something risky or kinky, he got his sexual juices flowing by fantasizing about one or more of his favorite anxious seductions.

He recalled several instances beginning as an adolescent when he had lost his hard-on because he was so nervous. But it would always come back—something he could no longer count on. One day Brian cut to the heart of his dilemma: “My body can’t handle the danger anymore, but I’m not turned on without it.” He had actually known this for quite some time but had never been able to articulate it so clearly. Now he had a way to understand why the comfort-building agenda of his previous therapy had made him so resistant. As is always the case in therapy, his resistance contained an unspoken message: “How can you expect me to solve my erection problems by relaxing when it’s anxiety that turns me on?” Vetoing the therapy was a subconscious attempt to preserve the eroticism he had always known.

Brian’s bind is far from unusual. Sex therapists regularly encounter men—and sometimes women too—who seem determined to avoid the comfortable, nonperformance-oriented touching that has helped thousands to resolve their sexual problems. Unfortunately, relatively few therapists are prepared to grapple with the untidy fact that anxiety isn’t just a pesky impediment to be banished as efficiently as possible. The neat-and-clean view of sexuality that dominates modern sex therapy has little to offer someone like Brian.

What he needed was to have the awkward truth about his inner conflict recognized; comfort and arousal had become hopelessly incompatible. For many years Brian’s CET, with its focus on the dangerous edge, had enabled him to transform anxiety into a source of excitation—well worth the occasional disruption of his sexual functioning. But now anxiety-the-aphrodisiac had become anxiety-the-erection-killer.

Once Brian understood what was going on, he invited Julia to join us for couple’s therapy, an invitation she eagerly accepted.3 As they worked together to rebuild mutually satisfying sexual interactions, Brian’s attachment to anxiety as an aphrodisiac and his concern that relaxation was incompatible with arousal were an open and regular part of our discussions.

EMOTIONAL APHRODISIACS IN CONTEXT

Virtually any emotion can either promote or negate arousal. While some people are able to put up with very high levels of even the most potentially disruptive emotions, others can tolerate practically none at all. A person’s response to emotion can also change over time, often dramatically, as it had for Brian. What had brought Brian’s conflict with anxiety to the breaking point?

For one thing, Brian was getting older. Most men recall a time in their teens and twenties when erections were triggered reflexively by almost anything. Young men manage to get and keep erections under the most awkward conditions—such as fumbling nervously in the backseat of a car while pretending to know what they’re doing. As men age, however, an increasing proportion can’t always take their erections for granted. So it was for Brian, who, entering his forties, was becoming increasingly susceptible to the arousal-blocking effects of high anxiety.

Equally important was the fact that he had grown to care for Julia more than any other woman he had ever dated. Since he wanted the relationship to work, a new form of anxiety entered the picture—a fear that sex might ruin his chances for love. Also, Julia preferred easy, comfortable sex in the safety of her own bed—the polar opposite of Brian.

You can see how a combination of changing circumstances can transform an aphrodisiac into an antiaphrodisiac. And when an unworkable turn-on collapses, it often leaves a gaping void where desire used to be.

Nancy and Burt: Alcohol recovery unleashes guilt

Nancy sat quietly with her head down while her husband, Burt, summarized their problem: “Nancy and I have always had a great relationship, and that used to include sex. But ever since she—I mean both of us—decided to stop drinking fourteen months ago, Nancy hardly ever wants it anymore, which is a big problem for me.” The room was practically pulsating with Nancy’s awkward silence.

Finally, with her face contorted by a blend of shame and exasperation, she offered in a barely audible voice the explanation that Burt seemed to be demanding. “It’s just that I feel so inhibited since I stopped drinking,” she whispered. “I didn’t realize how much I depended on a few drinks to loosen me up. I can hardly stand to have sex anymore.” With the word “stand” her voice took on a noticeable authority. The lady was most decidedly turned off.

They both seemed relieved when I told them that recovering from alcoholism (or any other drug addiction typically has significant and often unexpected effects on sexuality—even though few people discuss sex openly as part of their recovery. I must have hit a nerve because Nancy looked straight at me and proclaimed, “You got that one right. When I listen to people at AA meetings I feel like I’m the only one whose sex life is a total mess!” I suggested that the sexual changes they found so distressing were, in fact, a completely normal part of the recovery process. I invited them to open up the subject of sex to see what they might discover.

They had met at a party in the late 1970s. Nancy had just gotten her first job at an ad agency—a career that had flourished ever since—and Burt had been finishing a graduate degree in biochemistry. Within a few weeks they were living together. Each felt a part of the “sexual revolution” and relished sexual freedom and experimentation. Even after they married a few years later, they continued to be adventuresome by reading sexy stories to each other, acting out fantasies, and making love outdoors.

At first, a couple of glasses of wine or a few puffs of marijuana seemed to be harmless preludes to sex. Burt didn’t realize there was a problem until years later when he became concerned that Nancy was drinking much more—and so was he—and that they rarely had sex without getting high.

Burt hadn’t realized Nancy was never really the sexually free woman she appeared to be. Brought up in a strict family, educated in Catholic schools, encouraged by her grandmother to become a nun, she saw her sexual curiosity as horrifying to her mother and an affront to God. When she was an adolescent, sex with her first boyfriend made her both horribly guilty and incredibly excited.

As a college student in the 1970s, she embraced feminism and sexual freedom, rejected Catholicism, and found a supportive network of friends who shared her ethic of unfettered self-expression. As Nancy put it, “I thought of myself as a free thinker and rebel. Mom’s disapproval made me guilty but it also inspired me.” During that same period she discovered that a glass or two of wine helped relax deep-rooted inhibitions that weren’t changing as readily as her ideas.

Sex with Burt was exciting and satisfying before they got married. “We were so experimental with each other,” Nancy explained, “I actually enjoyed the guilt. I thought of us as coconspirators, saboteurs of a dying morality. We had a ball.” But after they married, Nancy’s strict upbringing suddenly reasserted itself. She established a closer connection with her mother and a renewed sense of loyalty to the expectations and ideals with which she had been raised. The two glasses of wine that once had calmed her inhibitions no longer did the job. The increasing physical tolerance that marks the biochemistry of addiction was abetted by a mounting psychological conflict that required ever greater doses of alcohol to quell.

Although Burt knew little of Nancy’s inner struggle, he was painfully aware that sex between them was losing its spark. He interpreted Nancy’s sagging desire as confirmation of his lack of attractiveness. He became so distraught that even though he worried about Nancy’s drinking, he sometimes encouraged her to drink because once in a while she would let go and become her old fun self again.

Their problems escalated when they started discussing having a baby. They both knew the risks associated with drinking during pregnancy, but Nancy couldn’t stop. Eventually, their marriage was wracked by drunken disagreements. The alcohol that had first entered the picture as beneficial gradually made everything worse. On the brink of separation they went to their first AA meeting together.

Burt found it relatively easy to stop drinking. Nancy too felt much better after a few weeks of sobriety. Their fighting mostly stopped, and she looked forward to the day when they could finally have a baby. Yet as her commitment to recovery took hold she felt increasingly sexless, which in turn forced her to examine her eroticism with an honesty she had never attempted before.4

Now that you have seen how negative emotions can cause a great deal of trouble, I hope you won’t conclude—as many sex therapists and educators erroneously do—that anxiety and guilt are solely the enemies of good sex. If that were the case, eliminating the destructive side effects of these emotions would be easy because few people would be drawn to them in the first place. However, the paradoxical perspective prepares us to accept a more complicated reality. Only by recognizing the untidy fact that emotions function as either aphrodisiacs or antiaphrodisiacs can we empathize with the struggles of people like Brian or Nancy. Only when we see the true nature of their dilemma do new possibilities become visible on the horizon.

TROUBLESOME ATTRACTIONS

Sexual attractions are among life’s elemental pleasures. The simple act of noticing another or being noticed stimulates aliveness and vitality. Most people you find attractive are just passing treats for the eyes, although some become objects of longing or characters in fantasies. Not all attractions are pleasant, though. The lonely, especially those convinced of their undesirability, find the lure of a beautiful other a painful reminder of deprivation.

Whether we’re looking for a casual partner or a lifelong companion, most of us defer to our attractions despite considerable evidence that they can’t always be trusted. After all, attraction is often based on as little as one compelling feature, such as terrific breasts or a beguiling smile—hardly sufficient reason to pursue a potentially life-changing involvement.

The attractions that stir you aren’t nearly as straightforward as they initially appear. When you feel an irresistible response to someone, your CET is probably being stimulated, although you may have no idea why this particular person is affecting you so strongly. Attractions that strike a deep inner chord do so because of a mysteriously complex and multidimensional psychic resonance. When you are strongly drawn to someone, do subtle clues and intuition allow you to perceive things about them that are normally hidden from view? Or is the object of your desire simply an appealing blank screen onto which you project a preexisting image from within yourself?

In my view, strong attractions are a baffling mixture of heightened perception, fantasy projections, and pure chance—so thoroughly intermingled that no dependable method exists for sorting them out. No wonder some attractions work out well while others are disastrous. Sometimes what you think you see is precisely what you get. At other times you may feel shocked and betrayed to realize that you are involved with someone who is not at all the person you thought. Attraction is a meaningful toss of the dice, neither a rational choice nor mere happenstance. With luck, experience has taught you valuable lessons about how to manage your attractions so that they work for rather than against you. This is perhaps the most anyone can reasonably expect.

Unfortunately, some people aren’t that lucky. You’ve probably known people who seem to repeat the same mistakes, whether in sex or love, consistently selecting partners who aren’t good for them or gravitating toward situations that turn out to be hurtful or frustrating. At first, you might think they’re just having a streak of bad luck. But as similar scenarios are repeated, you naturally begin to wonder whether an unseen script directs the participants toward a predetermined conclusion. And if you are the person experiencing such unsatisfying repetitions, you’re undoubtedly pretty discouraged.

In this section our focus is on those consistently troublesome attractions that cannot be explained by bad luck alone. Your knowledge of the erotic mind can help bring to light hidden erotic motivations with the power to excite you even as they are pulling you in directions incompatible with fulfillment. Virtually any CET contains the potential for a wonderfully gratifying involvement or for a painful replay of an old story—or a head-spinning combination of the two.

LONGING, LONG SHOTS, AND LOST CAUSES

Men and women who are sexually drawn exclusively to available partners, it they exist at all, are in a distinct minority. Who hasn’t felt attracted to someone hopelessly out of reach? Some objects of longing, such as celebrities, nameless faces in magazines, or fascinating strangers admired from a distance, don’t even know you exist. Others are fantasy figures borne of pure imagination. Like most people, you may have yearned for someone who was already in a relationship, too young, or uninterested in you regardless of how strongly you felt.

In the course of your lifetime you will almost certainly know the bittersweet excitement of desiring a partly available partner, happy to date or have sex with you but unwilling to get emotionally involved. If you’ve ever fallen under the spell of someone who vacillates between enthusiastic responsiveness and aloof detachment, you know firsthand how the intermittent reinforcement provided by an ambivalent lover makes you feel like a rat in a laboratory experiment. You press the button for a crumb of food even more frantically when the crumb is delivered occasionally and unpredictably.

Some people protect themselves from the pain of unfulfilled yearning by blunting their desire or by acting as if they’re without emotional need. Others try to circumvent longing by responding only to people who pursue them, while steering clear of those they most desire. Although these strategies shield them from the pain of unrequited desire, the cost is reduced vitality and spontaneity. Luckily, most of us forge a workable, if imperfect, balance between the lure of yearning and the annoying reality that most attractions are destined not to be mutual.

Some people, however, seem unable to achieve such a balance. For them the experience of longing, whether or not they fully realize it, is the centerpiece of their eroticism. No longing, no turn-on—end of story. Relying on subtle signs and well-honed intuition, they are invariably attracted to those who are unavailable, confused, ambivalent, of the “wrong” sexual orientation, or who live far away. They can sniff out long shots and lost causes with amazing precision.

Yearning enthusiasts become adept at zeroing in on partners who are somewhat available, or very available part of the time, or who hint that they might become more available in the unspecified future. Longing-based involvements are passionate, stormy, and—at key moments—profoundly moving. Unfortunately, those who genuinely seek long-term relationships often discover that their commitment to longing as the source of excitement turns out to be incompatible with their ultimate goals. The thorniest challenge of longing-based eroticism is neither desire nor arousal—these are easy. The hard part is fulfillment.

Maggie: Master of the chase

With the wisdom that comes from tough experience, Maggie spoke a fundamental truth: “The most painful relationships to give up are the ones that never were.” She was referring to a year of wrenching grief that had followed the inevitable end of a four-year affair with a married man. But on a deeper level she was summarizing a realization that, with few exceptions, her strongest attractions had always been for men whom, in one way or another, she couldn’t have. Yet she dreamed of an enduring bond with someone who would desire her without reservation and enthusiastically choose to be hers exclusively. She thought she wanted a man she wouldn’t have to pursue.

There was no logical explanation for her inability to find such a man. A bright, witty elementary school teacher in her mid-thirties, with a pleasing face, a shapely body, and a smile that exuded kindness, she obviously had much to offer. Over the years several men had pursued her. Yet she voiced a complaint I have heard often: “The ‘normal’ guys—the stable, dependable ones who would make great husbands—bore me. The exciting ones are all spoken for or on the run.”

Although her latest affair had been the only one with a married man, four others had many similarities, beginning with an energetic youthfulness she found irresistible. Each also had a flair for adventure, both in and out of bed, and a knack for playful spontaneity. All her lovers had also been unreliable at times and could not be counted on to follow through with plans, return phone calls, or remember special dates—important symbols of love for Maggie.

She liked men with a rebellious streak, so, not surprisingly, all her boyfriends vigorously refused to be tied down. Yet in each she perceived a vulnerability that intrigued her. “In spite of their precious independence,” she once said, “they all looked to me for stability and understanding.” Maggie had always been an ultra-responsible “good girl” who always could be counted on to be cooperative, helpful, sensitive, and obedient. Consequently, although she felt miserable whenever lovers let her down, she admired their freedom to slough off so easily the obligations that dominated her.

When it came to intimacy—what Maggie said she longed for most—all her lovers vacillated between openness and avoidance. The emotional expressiveness that excited her was always counterbalanced by a fear of being possessed. “It’s almost as if they see me as their mother,” she mused. During her first few months of therapy Maggie eagerly theorized about the psychology of each former lover, yet it was exceedingly difficult to get her to focus on herself. As is so often the case for those in the throes of longing, the other person held the key to everything. The goal was always the same: to identify and overcome their hangups. In a rare moment of self-reflection she acknowledged her motivations: “If I could just win them over I would feel loved.”

“And what if a man didn’t need to be won?” I asked. “What if he wanted to love you?” After a long silence she answered, “I’m not sure I could handle it.” That’s when I knew Maggie was ready to direct the spotlight inward, a process that brought her face to face with her commitment to longing as her chief erotic stimulus as well as her reluctance to accept gratification.

At first, Maggie described an almost idyllic childhood. But as she relaxed her automatic tendency to make things look good, a more realistic picture emerged. She never doubted her mother’s love, yet Mom usually seemed overwhelmed by responsibilities and duties. “I always had a sinking feeling that Mom was close to tears,” Maggie recalled. “I knew she was terribly unhappy and it was my job to make it all better,” a task at which she usually failed miserably despite her best efforts.

Even as a small girl Maggie knew that a major reason for Mom’s unhappiness was that Dad worked long hours and was often on the road. When he was home be would be absorbed in the newspaper or TV. He generally rebuffed requests for companionship or conversation, whether from Maggie or her mom. Maggie later learned that her mom often suspected he was having an affair, although she never confronted him. Maggie too was unsure of her father’s love, since she rarely received more than perfunctory attention from him, and hardly any of the heartfelt affection she craved.

As an adolescent Maggie found comfort in romantic stories and daydreams, most of which revolved around themes of postponed fulfillment—but always with happy endings. The imagery of yearning dovetailed with the affection-starved atmosphere of her home. In her high school boyfriend she saw the key characteristics that would consistently attract her: a devil-may-care but good-natured rebelliousness that was a natural complement to her nice-girl persona combined with a capacity for exuberant emotionality that was noticeably lacking in both her parents. For two years their relationship went well, though Maggie always wanted more closeness than what she got.

After graduation they went their separate ways. A few years later when she heard he had fallen in love and married his college sweetheart, Maggie confronted another key feature of her eroticism: a persistent undercurrent of grief and loss. Subsequent relationships all had similar outcomes—often with another woman getting, with apparent ease, the very things Maggie had struggled for unsuccessfully. Each time a man broke a date, stood her up, or withheld affection, she experienced a flood of grief, as if she were being abandoned yet again. She could only be comforted by the apologetic voice and soothing touch of her lover. When that happened her sadness would melt in a tidal wave of passion, and for a moment she would feel whole.

Her affair with the married man had been the most painful of all. From their first encounter she was convinced that he was the man she had been searching for, the man who possessed all the characteristics that fascinated her. He appeared to be crazy about her too and would often express the wish that they could be together always. He never actually promised to leave his wife, but Maggie assumed he eventually would, since he regularly spoke of a lack of love and sex in his marriage. Yet each time he chose to spend holidays or other special occasions with his wife, Maggie sank into despair. Eventually, she could stand it no longer and broke off the relationship. Unfortunately, she had been depressed and obsessed ever since. Sometimes she resorted to desperate acts such as parking in front of his house for hours waiting to catch a glimpse of him and his wife together or telephoning them and hanging up.

REPETITIONS AND REVERSALS

Maggie’s story highlights one of the most puzzling questions about all troublesome attractions, whether or not they revolve around longing: Why do so many of us repeat erotic patterns that have proven to be sources of suffering and lack of fulfillment? The most obvious answer is that our attractions, no matter how troublesome, work. Despite the pain they ultimately cause, at critical moments they are gloriously successful at generating ecstatic passion. It is difficult to overestimate what potent rein-forcers such passions are. Luckily, most of us learn from our failed relationships lessons that eventually steer us toward more workable partnerships.

Repetitive, problematic attractions are not so easily modified, which is why some people have, in recent years, labeled them love addictions. Calling Maggie’s tragic search for love an addiction may provide an illusion of understanding. If, however, we genuinely wish to uncover the sources of difficult attractions we must reject easy labels and venture inward where the erotic mind has its own ways and reasons.

Maggie first encountered longing in response to the pain of not feeling loved by her father.5 Unfulfilled cravings for affection defined the key problem her CET was trying to resolve. As her eroticism evolved she discovered—but only semiconsciously—that by continually placing herself in positions of longing she could convert her pain into passion. Logic suggests that someone in Maggie’s position might be drawn to men who, unlike her father, would be naturally warm and loving. And true enough, the men she found most irresistible were capable of great warmth and tenderness, but never consistently.

To select a man who would love her wholeheartedly, Maggie would need to bypass the very dilemma her CET was designed to reverse: how to get someone who seems ambivalent to change his mind and love her without reservation. At her most passionate moments that’s exactly what happened—at least for a while. Unfortunately, her CET forced her to select men who were not readily available, otherwise she couldn’t anticipate the reversal that was the overriding goal of her eroticism. Her passion only sprang to life when fulfillment seemed possible but just beyond her grasp. In a moment of stunning clarity Maggie articulated the essence of her problem: “What really turns me on is almost being loved.”

Maggie’s dilemma is far from unique. Millions of people gravitate toward partners who appear to possess characteristics similar to those of significant others—parents, siblings, special friends—who have let them down in the past. Their goal is not primarily to perpetuate the pain (although this tends to be the most frequent outcome) but rather to reenact hurtful situations in hopes they can be reversed—the pain transformed into passion.

A complete understanding of Maggie’s determination to avoid fulfillment requires one more piece of the puzzle, one Maggie found very difficult to accept. It’s true that Maggie’s first object of longing was her father, but it was through her emotional alignment with her mother that she learned on a day-to-day basis the ways of longing and sadness. Remember how desperately Maggie struggled to make her mom feel better? While it doesn’t make sense logically, it is difficult for most of us to grow beyond our parents, particularly the one after whom we most model ourselves. For Maggie to receive the love she craved she had to follow a path radically different from her mother’s, which seemed to her a terrible act of disloyalty.

PITFALLS OF POWER

Longing-based erotic scripts are by no means the only ones with the potential to turn against you. Regardless of the details that energize your CET, what makes your most exciting turn-ons so intense is that they soothe old wounds. Yet there’s always the risk your erotic scripts will create the very problems they’re trying to resolve, whether these problems originate within the family or within one’s peer group.

Derrin: A need for control

Tall and lanky, with closely cropped hair and a row of pens clipped to his shirt pocket, Derrin looked just like the “technophile” he pronounced himself to be. He had a very successful career as a computer systems engineer with an income well into six figures, the respect of colleagues, and the satisfaction of regular new challenges he felt confident about tackling. He had recently been hired to teach a college course in computer science and, much to his surprise, had become a popular instructor. Students admired his soft-spoken intelligence, and some looked to him as a mentor.

Derrin wasn’t accustomed to such popularity. His own life as a student had combined academic success with a chronic sense of social failure and isolation. He told me of a recurring nightmare in which he’s running toward a train station to join his classmates for a field trip. In the distance everybody’s joking and jostling as they board the train. He struggles to run faster but his legs feel like lead. He reaches the train just as the doors close and it pulls out. As the windows pass by, a few kids make silly faces at him but most are having too much fun to notice. “All my life,” he lamented, “I’ve been the odd man out.”

The only child of a fairly normal family, Derrin was consistently praised for his scholastic achievements. He liked school because he did well, but he also hated it because of his isolation there. With the onset of puberty he felt more than ever like the outsider. He often eavesdropped as other guys traded stories of their sexual exploits yet avoided school parties and dances, retreating instead into his studies.

One day he discovered his father’s collection of sexy magazines stashed in the garage, and later in his room he pored over them. Sure he knew the basic facts about sex, but he had never felt such overwhelming sensations or such a compelling urge to touch himself. He had his first ejaculation that night—actually four or five over the course of several hours. Thereafter he developed an active fantasy life populated by lusty women eager to satisfy his every demand.

Meanwhile his relationships with real women remained distant and awkward. The ones he found most appealing wouldn’t give him the time of day. But not in his fantasies. One day Derrin handed me a written copy of his most exciting one, which clearly revealed his creative formula for turning the tables:

I’m sprawled out naked on a large bed in a dimly lit room. A big-breasted nymphomaniac is seducing me with a provocative striptease. When she removes her slip she runs it across my body. She can see I’m turned on but I conceal from her how much. After a while I pretend to be bored and turn away. Then another woman stimulates me even more aggressively until I’m on the edge of coming, still playing it cool. At the foot of my bed three women wait their turn. At the climax I throw the most attractive one down on the bed and fuck her, while the others suck and stroke my balls and ass in a wild frenzy. When I can’t hold back any longer I pull out and shoot all over them.

Whereas in real life Derrin expects to be ignored by the women he desires, in fantasy the women not only aggressively break through his isolation, they actually compete for his attention, which he enjoys withholding by acting bored, until he becomes the dominant stud he always wished to be. Derrin confirmed for me that when he “shoots all over them,” he’s really “letting them have it”—sweet revenge for past indignities.

As we saw in Chapter 5, fantasies of dominance, often with an undercurrent of revenge similar to Derrin’s, are common among both men and women. The problem for Derrin was a social life so desolate that he had few opportunities to learn about sexual interactions with real women until he entered college. There he explored dating and sex but consistently selected shy, passive women whom he felt reasonably confident he could dominate in bed even though he was attracted to sophisticated, independent women who knew how to compete in a man’s world. These most alluring women intimidated him.

With his newfound popularity as a teacher he encountered a tantalizing but risky new opportunity to assume a dominant position. Against his better judgment he pursued sexual relationships with a few of the women who sought him out after class. It was enormously exciting to have access to intelligent, confident young women—the kind who had always seemed beyond his reach. The sense of importance that came with his position counteracted his usual shyness. For the first time he felt socially and sexually competent.

Also for the first time he fell in love—with a sexy sophomore named Erica. A typical date involved long discussions over dinner about philosophy, new technologies, and her career plans and personal problems. The fact that she obviously looked up to him aroused him immensely. Each date inevitably culminated in fiery sex—similar to his fantasies, but without any overt sign of revenge. “She truly admires me,” Derrin explained. “I don’t have to get even with her.”

After a few months Erica began expressing her own ideas and opinions and deferred less to Derrin. Although he had complicated the teacher-student relationship by sexualizing it, she was nonetheless responding in her own best interests by growing stronger and more independent. She insisted on dating other guys and was offended when Derrin assumed he had a right to make demands on her. Soon the affair unraveled with plenty of hurt feelings all around. During the painful aftermath Derrin entered therapy.

The teacher had unexpectedly become the student. Now he was being forced to face some chilling realities. To begin with, deep inside he felt just as vulnerable and alone as he had in high school, and those feelings could clearly not be resolved by professional successes, no matter how impressive. Beyond that, the role of dominance in which he found solace and excitement turned out to be almost purely defensive, perfected in isolation but unworkable in real life. Only with passive women who bored him, or within the safety of a superior social position, could he sustain the illusion of control. In either case an enduring connection was impossible. As he uncovered the pain at the core of his attractions, he realized the time had come to risk a new direction.

Maggie and Derrin illustrate how few of us have as much say as we believe in choosing our attractions. We are magnetically pulled toward partners with whom we sense the opportunity to assuage a festering wound or to compensate for our incompleteness or inadequacy. Happily, sometimes that is exactly what happens. But such attractions, even as they hold out the hope of joyous solutions, also carry the possibility of drawing us backward toward repetition rather than forward toward growth. Only by recognizing this paradox can we embrace the adventure of attraction with our eyes as open as our hearts.

LOVE-LUST CONFLICTS

One of the key challenges of erotic life is to develop a comfortable interaction between our lusty urges and our desire for an affectionate bond with a lover, a bond that combines tenderness and caring with passion. In the complex world of eroticism, few people can avoid being pulled in conflicting directions, at least at times, by their dual desires for emotional closeness and raw excitement. The situations and people that stimulate us sexually may be quite different from those that make us feel affectionate. Even so, most of us learn how to accommodate our competing urges and, when the time is right, to risk the glorious roller-coaster ride when love and lust converge.

It’s a sad reality that cultures and families often seem hell-bent on making the interplay of love and lust infinitely more difficult than it needs to be. The framework for adult love-lust interactions is sketched out during childhood and adolescence. Adult lust evolves out of simple experiences of sexual and sensual curiosity. The precursors to adult love are early emotional attachments, first to Mom, then to the larger family, and eventually to a community of friends and acquaintances. When kids play house, mimic favorite TV characters, simulate flirtatious poses or embraces, or initiate or reject nudity or sexy games with their peers, they’re engaging in the important work that Dr. John Money calls “sexual rehearsal play.”6 Through positive sex play kids learn about their own and others’ bodies. At the same time, the complex interactions and negotiations required by their games provide opportunities for practicing skills of social conduct.

When adults try to protect children by forbidding sex play with age-mates, the message is powerfully communicated that their curiosities are bad, setting the stage for a later mistrust of lust. These “protected” children are frequently unprepared to handle the more demanding interpersonal challenges of adolescence. As adults they often end up confused or in conflict about matters of love and lust.7

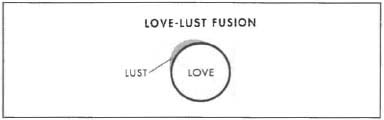

For those who hold the twin beliefs that love is good and lust is bad, two basic strategies are available for dealing with this dichotomy. One approach seeks to tame or to purify lust by fusing it with love so that lusty urges are interpreted as love, an especially common response to sex-negative training among women. Rushes of sensation that many would call lust are interpreted as love or affection. A love-lust fusion can be visualized like this:

When sex must always be joined with love, even casual sex can become infused with emotion and meaning. Unfortunately, this special intensity is typically followed by the realization that the partner isn’t feeling the same way. More often than not, the dream of lust redeemed by love quickly turns to loneliness. The inability to experience lust as separate from love clouds one’s judgment and is responsible for incalculable unnecessary suffering.

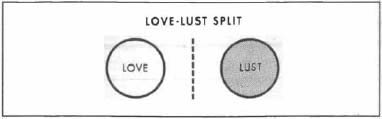

Another response to love-lust conflicts, more common among men, is to protect the purity of love by creating an invisible barrier between it and lust so that a person becomes unable to feel both at the same time or with the same person. The splitting apart of love and lust can be visualized like this:

When someone pursues lustful aims with complete detachment from tenderness and affection, erotic attention narrows to a laser like focus on maximum genital arousal. The result is often a level of excitation that is qualitatively different than any other kind—hotter, more insistent, a unique psychophysical high. Unfortunately, love-lust splits make it difficult or impossible to build and maintain sexual relationships because affection intrudes, reducing or obliterating the sought-after intensity.

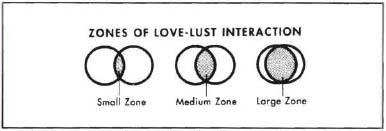

Neither love-lust fusions nor splits are compatible with sexual well-being because both result from a destructive and tragic conviction—often vigorously denied—that lust is disgusting and incompatible with love. The capacity to experience genital arousal together with emotional intimacy falls within what I call the zone of interaction, where love and lust overlap. This zone may be large or small and can be visualized like this:

Disagreements abound regarding the optimum amount of love-lust overlap. There are those who strongly believe, as a matter of morality or preference, that eros reaches its full potential only to the degree that love and lust are experienced in tandem. Others feel especially alive and vital during experiences of uncomplicated lust. Disputes about the best relationship between love and lust will never be settled because there is no single ideal arrangement.

My observations as a therapist have convinced me that erotic health is possible as long as some degree of love-lust interaction exists at least some of the time. Not surprisingly, the convergence of love and lust is normally at its fullest during the limerent period of a romantic involvement. At such times love and lust usually feel totally unified. As intimate relationships develop, however, the zone of interaction normally grows smaller and less consistent. Virtually all long-term couples grapple with this change, and hardly any are pleased about it. In most cases, however, as long as affection and lust continue to interact to some degree, the partners stand a good chance of finding ways to continue enjoying sex with each other.

PRISONERS OF PROHIBITION

We have devoted considerable attention to the naughtiness factor and the way it brings the thrill of the forbidden to all sorts of encounters and fantasies. You’ve probably noticed in your own life how a sense of raunchy fun can add a welcome spark to already satisfying sex. The ability to transform naughtiness into arousal begins as a creative adaptation to the distressing fact that the adults upon whom we depend for survival don’t approve of our sexual curiosity.

When you have fun with naughtiness, you acknowledge the restrictions you faced as a child while asserting that, to a significant degree, your desires have triumphed over the forces that tried to suppress you. You have grown sufficiently free to use prohibitions for your own enjoyment and play. Many people, however, grew up in homes so permeated with antisexual restrictions that the drama of violating prohibitions has become the central feature of their eroticism. These people are prisoners of sexual prohibition, and it’s no exaggeration to say that they have been victimized just as surely as if they had been molested.

For prisoners of prohibition every opportunity for enjoyment sets off a frantic inner conflict. When they feel aroused they’re awash with guilt. If their inhibitions are temporarily swept aside by desire, they pay later with remorse and shame. This conflict is so unpleasant that some people develop sexual aversions and go to great lengths to avoid becoming aroused. In the worst cases perfectly normal sexual stirrings actually trigger panic attacks.

The opposite reaction takes place in those who become obsessed with sex, compulsively reenacting the very behaviors that were most forbidden. They keep their eroticism alive by sustaining a hidden sex life, cut off and thus protected from antisexual judgments. If these secret sex lives are eventually exposed, it is often to the amazement of shocked friends, family, constituents, or congregations.

Many sex offenders are prisoners of prohibition who can only become aroused when they are actually violating laws, risking legal punishment and social censure. But most prisoners of prohibition are not sex offenders—and never will be. Instead the perpetual tension between antierotic training and persistent forbidden desires fuels an internal struggle as compelling as it is grueling. They harm no one except themselves and those who try to love them. In most cases their torturous secret comes fully to light only when they try to form an enduring sexual bond.

Ryan and Janet: Too close for lust

Ryan was distraught over his relationship with Janet, his new girlfriend. He told me how important she was to him, how doubtful he was about his ability to succeed at romance, and how determined he was to make a go of it. Ryan’s relationship with Janet was the most affectionate and tender he had ever known. “But,” he continued with a deep sigh, “I’m not handling it very well.” He was embarrassed to admit that even though he found her very attractive, he had never been able to ejaculate with Janet. As we discussed his predicament it soon became apparent that his inhibited ejaculations were a manifestation of a much more serious problem: a gaping chasm between his lusty urges and his desire for love and affection.

I asked him to recall his earliest feeling or experience that seemed, in retrospect, to have been sexual. Most clients need to think about this question for a while, but Ryan knew his answer instantly. Around age four or five he had been casually playing with himself, enjoying the warm, tingling sensations between his legs. This simple memory became permanently etched in his mind when his father walked in on Ryan’s sensuous reverie, flew into a rage, ranted about hell and evil, and commanded him never ever to do that again, terrifying little Ryan half to death.

“From that moment on,” Ryan proclaimed, “I knew I must restrain myself. Soon I also knew I was obsessed with my little prick, how good it felt, and how bad I was for wanting to touch it.” He went on to explain that, with plenty of twists and variations, he still felt essentially the same way as a middle-aged man. He craved love yet was driven by an insatiable appetite for nasty sex. In the past he had often hired prostitutes but not since meeting Janet. Thus far, though, he had been unable to resist even stronger urges to masturbate while talking on telephone sex lines. And he still sneaked out to X-rated bookstores in the black of night in search of pornographic videos and magazines. He was fascinated by graphic depictions of down-and-dirty sleaze.

He was the first person I ever met who called himself a “sex addict,” at least ten years before the term became fashionable. The connotations of addiction accurately captured the out of control, compulsive quality of his behavior. But his insistence on casting himself as an addict who had to “kick the habit” only intensified the grueling struggle that fueled his obsession. Like most of today’s “sex addicts” Ryan was less hooked on sex than on fighting with it. He felt the helplessness of a drug addict because for him forbidden desires escalated in tandem with the need to resist them. His excitation was always ultra-hot, but there was little or no lasting enjoyment. For as long as he could remember, he had most assuredly been a prisoner of prohibition.

No wonder Ryan was easily orgasmic while masturbating to porn or with anonymous phone partners. He considered his fantasy women sluts with whom he could freely express his depraved, lusty self. The fact that his fantasy partners weren’t actually present also made it easier for him to express his impulses in unedited form, although he worried that one day someone would recognize his voice and expose his secret. Because he admired and respected Janet, he felt self-conscious and inhibited—cut off from the roots of his eroticism. Although their shared affection and sensuality felt marvelous and usually produced an erection, he was unable to surrender to lust and generate sufficient erotic intensity to push himself “over the top” to orgasm.

Once Ryan understood his conflict he asked Janet to join him in couple’s therapy. He wisely decided that telling Janet about his lusty exploits outside their relationship would only hurt her, so he kept those details to himself. But he was determined to tell Janet about the inner conflict that was preventing him from feeling sexy with the woman he loved.

ECHOES OF OEDIPUS

Since I already had a relationship with Ryan, Janet and I had a few individual sessions. She felt great admiration for Ryan, whom she saw as talented, highly principled, and committed to making the world better. Janet felt frightened because she had previously loved two other men whom she had also admired. Both relationships ultimately failed, largely due to sexual incompatibilities. She lived in dread that history was about to repeat itself.

Janet had always been attracted to kind, intelligent men, beginning with her father, whom she adored. Her mother, whom she also loved, became terminally ill when Janet was eleven and was bedridden for almost two years before she died. Although her two brothers helped a little, Janet and her dad did most of the caring for her mom and kept the household going. Her father’s unwavering commitment to the family deepened Janet’s admiration. The two of them often cried together, comforted each other, and shared their hopes and fears.

Once we began couple’s work, Janet was very understanding when Ryan told her how he had learned from his father that sex was sinful. She was surprised to hear about Ryan’s current battle with lust but also relieved that Ryan’s troubles weren’t her fault. Together they agreed to venture into the sexual realm slowly through sensual touch and open communication. But before long Janet felt uncomfortable, especially as their touching expanded to include each other’s genitals. In an unexpected reversal of roles, the more at ease Ryan became with sexual contact, the more Janet avoided it.

During one pivotal session Janet confessed that sex with Ryan felt “almost incestuous.” Ryan looked shocked as she explained, “You and I are so close, sometimes I think of you more like a brother than a lover.” Very gingerly they opened a topic shrouded in the most powerful of all taboos: sexual feelings within families. Janet gradually realized that her incest fears were an unresolved aspect of her relationship with her father. During her mother’s illness and after her death, Janet had clung to him. But she also recognized, with considerable guilt and anguish, that his reliance on her as helpmate and confidante had felt “a little weird.” She explained, “I think maybe we became too close—not that anything sexual ever happened between us—just emotionally. I remember thinking, ‘Now I have to take care of Daddy,’ as if I were supposed to be his new wife.” She shuddered noticeably as she added, “I can’t believe I said that.”

This all took place as she was entering puberty. It surprised her that she couldn’t remember any sexual feelings at all during her adolescence. Clearly, she had unconsciously suppressed her sexuality to avoid complicating her confusing emotional bond with her father even further. Once she started dating, she typically formed platonic friendships with men. In three amazing feats of intuitive attraction she had selected boyfriends with whom she could be close but who, because of their own insecurities, were reluctant to have sex with her. Thus she had spared herself the daunting task of examining her incest fear, the one difficult aspect of an otherwise wonderful relationship with her father. By keeping the spotlight on her boyfriends’ sexuality rather than on her own, she had kept her own lust in check.

During our next session Ryan revealed that he often felt like his mother’s “little husband.” That day Ryan had been talking with his mom on the phone when she confided in him, as she often did, how lonely and unhappy she was with his father, who didn’t seem to care that much about her. As usual, Ryan was trying to comfort her when she whispered, “Oh, Ryan, you’re the only one who understands.” Although the exchange was all too familiar, a wave of revulsion suddenly engulfed his body, along with an overwhelming urge to hang up. Ryan added, “Sometimes she’s so damn needy it gives me the creeps.”

Almost everyone is aware of how damaging sexual contact with an adult can be for a child. Not so widely recognized, however, is that certain kinds of overclose emotional involvements between parent and child, even when no overt sex is involved, can make it very difficult for the child to integrate love and lust as an adult.

When Ryan and Janet made love, the combination of their intimate connection with sexual arousal apparently triggered old incest fears in both of them. When Ryan engaged in phone sex with sluttish fantasy women, not only was he acting out his identity as a depraved sex fiend, he was also directing his erotic attention toward someone as unlike his mother as possible. By separating love from lust he was honoring his father’s warnings while also steering clear of any interactions that might feel even vaguely

Love and lust are inseparable parts of a larger whole for some, while for others they are irretrievably disconnected. Most of us, however, express our eroticism somewhere in the gray areas where love and lust both relate and conflict. Only by realizing that the two experiences are separate can we avoid painful self-delusions; to lust is not necessarily to love. By also recognizing that love and lust can and do interact, we open the door to the deepest mysteries of eros.

COPING WITH TROUBLESOME TURN-ONS

Each individual’s CET evolves in response to the challenges and conflicts of early life. The erotic mind attempts to gain mastery over these problems by using the obstacles they present to stimulate desire and arousal. You can see how everyone in this chapter except Janet had learned to use long-standing conflicts quite successfully as turn-ons. But while most found plenty of excitation, they also discovered that their erotic scripts ultimately perpetuated the very problems they were trying to resolve.

If you identify with any of the troublesome turn-ons described in this chapter, the best thing you can do is to use the understanding you have gained thus far to help you recognize how your patterns of arousal are working against you. Without this awareness you must blindly follow the established path wherever it leads you.

Now is a good time to conduct a simple reassessment of your eroticism to see if you might be affected by any of the three types of erotic problems we’ve explored in this chapter:

Feeling side effects

Troublesome attractions

Love-lust conflicts

First, reconsider the emotions most prominent in your CET. You already realize that the full range of human emotions can energize your turn-ons and that some feelings—especially anxiety and guilt—can disrupt your body’s ability to function sexually. Consequently, if you’re grappling with a sexual dysfunction, pay careful attention to the emotional aspects of your CET. Keep in mind that, like Nancy and Burt, you may not easily recognize how guilty you actually feel, especially if you regularly rely on alcohol or other drugs to calm your inhibitions. Or, like Brian, you may have become so accustomed to anxiety in your sex life that you hardly even notice it.

If you’ve been unlucky in a string of relationships, could it be that you are reenacting frustrating or painful relationships from the past? Make a list of each of the people to whom you’ve been most strongly attracted in your life. What characteristics do they have in common? Can you identify difficulties from your early life that you’re still trying to fix or otherwise play out through your current relationships? Unresolved feelings from historically significant relationships, particularly those within the family, are natural aspects of attraction, so there’s no need to feel ashamed if you recognize them within yourself. The important thing is to notice if you keep trying to reverse a painful relationship from the past by unwittingly selecting partners with whom you are doomed to repeat it. This dilemma can only be resolved when you are willing to bring your motivations into consciousness.

Finally, consider the degree of connection between love and lust in your eroticism. It helps to sketch out your personal zone of love-lust interaction. As I demonstrated earlier in this section, draw or visualize two circles, one representing lust and the other representing love. Position the circles to show how much they’ve overlapped in your past as well as in the present. Like many people, you may have developed two parallel systems of attraction, one focusing on qualities you associate with sexual magnetism and the other emphasizing features compatible with intimacy and affection. Unless these sets of attractions allow for at least some degree of overlap, you’ll probably have trouble maintaining a long-term sexual relationship. On the other hand, if you find it difficult to distinguish between love and lust, you’re especially vulnerable to unworkable involvements. By recognizing where you stand, you can identify potential problems and prepare for constructive solutions.

Once you’ve acknowledged a troublesome turn-on, what should you do about it? In many instances confronting your predicament creates conditions ripe for growth. Luckily, the erotic mind is quite capable of making positive adjustments based on lessons learned from experience. In Chapter 8, “Winds of Change,” we’ll focus on how to nurture the creative, adaptable characteristics of your eroticism. In the meantime, nonjudgmental self-observation will help you reclaim the ability to choose.