8

WINDS OF CHANGE

Seven steps point the way

to sexual healing and growth.

Now that you’ve looked at some of the most perplexing, persistent, and unpleasant dilemmas of erotic life, you may be wondering how they can ever be resolved. If you or someone you care about has struggled with a troublesome turn-on, you know firsthand that it’s useless merely to wish for change. What’s needed is a plan of action that mobilizes your innate capacities for healing and renewal. This chapter is devoted to such a plan.

It is important to realize that change is intrinsic to the erotic adventure. For instance, as you discover new avenues to pleasure, your sexual repertoire naturally expands to accommodate them. Unfortunately, we must confront an unwelcome irony: the erotic patterns most in need of modification—the ones that create turmoil as well as excitation—are typically the most resistant to change. In other words, the more troublesome a turn-on, the tighter its grip.

Common sense might lead you to expect that the pain of problematic sex would be a powerful motivator for change. And in a sense this is true. People whose sexuality has become a source of distress usually want to change. Yet the same conflicts the person hopes to resolve may also produce extraordinarily high levels of intensity. Consequently, those who suffer the most from their erotic patterns often feel the most compelled to repeat them.

As a result of my work with hundreds of men and women who have successfully modified or expanded their turn-ons, I’ve identified seven pivotal steps that consistently lead to positive erotic change:

Step 1. Clarify your goals and motivations.

Step 2. Cultivate self-affirmation.

Step 3. Navigate the gray zone.

Step 4. Acknowledge and mourn your losses.

Step 5. Come to your senses.

Step 6. Risk the unfamiliar.

Step 7. Integrate your discoveries.

Steps 1 and 2 set the stage for change by helping you define what you’re trying to accomplish and how you expect to benefit. Steps 3 and 4 prepare you for two difficult challenges: feeling lost without a map as you leave the comfort of the familiar and coping with the grief that is a commonly ignored aspect of significant change. Steps 5 and 6 show you how to experiment with specific behaviors and use them as guides to your untapped potentials. Step 7 is concerned with making change endure.

STEP 1:

CLARIFY YOUR GOALS AND MOTIVATIONS

Some of the most welcome changes occur spontaneously. Eroticism is constantly evolving as old turn-ons no longer satisfy and new possibilities for enjoyment appear as unexpected gifts. Under the best of conditions these changes are propelled by pleasure, without any need for conscious goal-setting.

Unfortunately, not all sexual changes are so easy or pleasurable. Well-established erotic patterns often continue exerting a major influence long after they have ceased to be truly satisfying. Sometimes we lose touch with the pleasure-based motivations that normally guide us. When desired or necessary changes aren’t happening automatically, we need to think long and hard about exactly where we wish to go. Then, by clarifying our reasons for wanting change, we can unleash the necessary energy and determination.

THREE KEYS TO GOAL-SETTING

The kinds of goals you set and how you go about setting them can make the difference between moving forward and remaining stuck. In my experience there are three crucial guidelines for successful goal-setting:

1. Keep your goals simple, specific, and limited. Vague goals such as “I want a better sex life” or “I want more fulfilling relationships” are virtually useless. It’s not easy to define the essence of what you hope to accomplish, but the rewards are well worth the effort. “I want to be able to enjoy sex with someone I love” or “I want to learn how to get turned on without feeling anxious,” are examples of much more useful goals because they point you in a specific direction. Whenever you consider a goal ask yourself, “How will I know when I get there?” If you can’t say, then your goal probably isn’t sufficiently clear.

Try to avoid goals that call for sweeping change. Many people erroneously believe that building up a case against their entire eroticism will somehow increase their motivation for change. But if you believe you have to change everything you will end up changing nothing. Whenever I hear a client say, “My sexuality is completely screwed up,” I know his or her immediate goal is self-criticism—not change.

2. Pay much more attention to what you want than to what you don’t want. One of the biggest mistakes people make when they contemplate erotic change is to focus on what they don’t want to do—don’t be so inhibited, don’t be self-conscious, don’t ejaculate so fast. When erotic patterns are causing distress it’s easy to see how getting rid of problematic behaviors can look like the obvious solution. Those who think of themselves as sex addicts are especially prone to this mistake. They don’t realize that struggle is the fuel for all compulsions. When they fight with themselves they become more compulsive and out of control, not less. If you’re serious about changing, express your goals in the affirmative, with the emphasis on your ultimate destination and the concrete steps necessary to get you there.

3. Honor your individuality. Helpful goals must be specifically tailored to who you are. The key is to begin envisioning your eroticism in its healthiest form. It’s a waste of time to base goals on abstract concepts about how eroticism “should” operate. Beware especially of goals that call for fundamental changes in your personality, for they will ultimately undermine your self-esteem and leave you feeling discouraged and helpless.

Be cautious about setting goals that lie completely beyond the scope of your experience. Sometimes this is necessary, of course, as in the case of someone who wants to feel sexy toward a lover or spouse even though he or she has never experienced arousal in conjunction with affection. Whenever possible, it’s a good idea to link your goals to experiences you’ve actually had in the past that are close to ones you’d like to have more often. With rare exceptions, even people whose erotic patterns are profoundly problematic can, if they are willing to look closely enough, identify moments that offer glimpses of their potential.

Goals that involve altering your sexual attractions are especially tricky. Attractions are as individual as fingerprints—and almost as difficult to change. Yet I’ve known plenty of men and women who were consistently attracted to a particular “type,” only to find they have fallen head over heels for someone they would never have considered desirable before. Nevertheless, keep in mind that attractions can rarely, if ever, be changed through willpower.

If you want to select different kinds of partners, be as clear as possible about which specific aspects of your attractions have caused you trouble. Most people who attempt to change their attractions make the mistake of assuming that their preferences need to be entirely transformed. This is rarely necessary. As we shall see, positive change frequently involves using old patterns in new ways.

TWO MOTIVATIONS: PUSHES AND PULLS

Like beacons, goals give us direction. But to mobilize the energy to move us toward these goals we need motivation. There are two fundamental types of motivations: pushes and pulls. It is important to distinguish between them.

Push motivations prod you into action when the discomfort of the status quo becomes intolerable. Unpleasant emotions—especially fear, guilt, hurt, loneliness, and desperation—are examples of compelling push motivators. For instance, Maggie wanted to break her penchant for chasing unavailable men because constant feelings of rejection were becoming unbearable. She was also afraid that time was passing and she might never find a lasting relationship.

Similarly, even though Ryan was tremendously excited by his compulsive pursuit of forbidden thrills through phone sex and porn, he felt increasingly distraught about his lack of choice in the matter. He was also haunted by images of being found out, ridiculed, and cast aside by family and friends. And he didn’t like being more interested in raunchy sex with sluts than loving sex with his girlfriend.

Different people are able or willing to tolerate different levels of distress before they actively pursue a change. If someone’s behavior causes them only distress they will probably change it quickly and with relative ease—unless an unconscious need for self-punishment compels them toward destructive repetitions. Change is more difficult when troublesome behavior is both distressing and rewarding.

Unlike push motivations, which require you to face your distress and be made uncomfortable, pull motivations promise potential rewards and benefits. Believable, enticing images of how your life can be more fulfilling are immensely helpful in keeping motivation alive even in the face of adversity.

Maggie was willing to consider stepping outside the familiar framework of unfulfilled longing not simply because she feared a life of loneliness but also because she had experienced moments of actual intimacy and was beginning to believe she deserved more of it. Similarly, Ryan was not only pushed by shame about being a prisoner of his taboo impulses, he was also pulled by a genuine desire to feel closer to his girlfriend.

ANTIMOTIVATIONS

When you set out to change an entrenched pattern, sooner or later you will feel inclined to back away from the very changes you seek. Psychologists call this resistance. All kinds of doubts and fears, both conscious and unconscious, can contribute to resistance. What if you fail? What are the implications of success? Could tampering with your eroticism ruin it? Will friends, family members, or sexual partners encourage you, or might they be threatened by what you’re doing? If your sexuality changes will you still recognize yourself? These concerns, along with a host of others, are antimotivators because they prevent you from vigorously pursuing your goals.

Antimotivators are as much a part of the change process as your goals and motivations. Because antimotivators are most likely to undermine change when they operate subconsciously, it’s smart to become as aware of them as possible. If you face your fears about change rather than suppress them you will be much better able to address what concerns you. Antimotivators contain crucial information about which courageous acts are called for—and when.

YOUR MAP FOR CHANGE

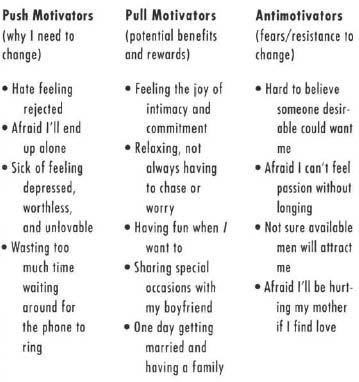

Successful and fulfilling erotic changes involve all three: push motivators, pull motivators, and antimotivators. To boost your awareness, put them all together on one piece of paper so you can see them at a single glance. Write the headline GOALS, and then list your objectives as clearly as you can.

Maggie’s Motivational Map

Goals:

- • To be attracted to someone available for a relationship

- • To only love someone who loves me in return

- • To develop other turn-ons besides longing

- • To let myself accept love

Next divide the area below your goals into three columns. Label the left column Push Motivators. As specifically as possible, list the reasons that you believe change is necessary. Focus on what concerns you about your eroticism—anything that causes pain or distress. Label the middle column Pull Motivators. Here spell out how you hope to benefit, either immediately or in the long run. Label the right column Antimotivators and list any fears and hesitations that might hold you back.

Resist the urge to edit as you write. Grant yourself freedom to be as irrational as you want. This map is for your eyes only, so no one else is going to judge it. Once you’ve listed everything you can think of, place a star next to the items about which you currently feel most strongly.

Now you have a picture of where you’re trying to go, why you want to get there, and the roadblocks you’re likely to encounter along the way. Keep in mind that goals and motivations are not static. Expect them to evolve as you become increasingly experimental. One of the advantages of writing all this down is that you can return to it, refining your list as you move along. See Maggie’s motivational map on the previous page. Notice how she has succinctly summarized all the key elements for her erotic growth.

STEP 2:

CULTIVATE SELF-AFFIRMATION

Those who set out to alter a troublesome turn-on commonly begin in a self-critical posture, vigorously focusing on what’s wrong with them. They doggedly cling to the conviction that somehow their judgments will bring about change. This mistaken belief is a major impediment to growth.

I’m not denying that constructive self-criticism can be a valuable stimulus for action. But when self-demeaning thoughts and feelings predominate, they ultimately sabotage your innate capacities for healing. The only alternative is to cultivate the ways of self-affirmation. To affirm yourself is, first and foremost, to assert your right to take up space in the world. Beyond that, it is an ongoing process of developing and expressing more of your truest self.

Many confuse self-affirmation with narcissism, a preoccupation with oneself that makes it difficult to recognize anyone else’s feelings and needs. In fact, narcissistic adults who seek continual recognition and praise are trying to compensate for a lack of genuine self-affirmation.

FROM STRUGGLE TO CONSENSUS

The moment you decide to make a change you initiate a series of interactions among two or more internal aspects of yourself. Perhaps one part of you has reached the end of its rope and is now desperate for change no matter how difficult, while another part clings to familiar patterns in spite of the pain and dissatisfaction they cause. Yet another part may only be concerned that you conform to external standards of behavior.

Ever since I successfully quit smoking after countless failed attempts, I’ve been fascinated by how people prepare themselves for change. Everyone I talk to who’s made a difficult transition instantly understands what I mean when I say that I was able to quit smoking because my entire being eventually came to an inner consensus. But I have yet to meet anyone who can explain exactly what this consensus is or how it is reached. Of two things I am sure. First, within you is a unifying force known as the Self that holds the key to reducing destructive internal conflicts.1 Second, compassion is the master emotion of positive change.

MOBILIZING THE POWER OF COMPASSION

Compassion is one of the most healing of all responses to pain and suffering—for both the giver and the recipient. It is the opposite of malice or indifference. When you feel compassionate toward someone who is hurting, you feel no inclination to judge them. In the same way, whenever you are able to direct compassion inward, self-criticism temporarily dissolves.2 Especially for those who grew up in abusive environments, healing depends on compassion.

Those who are not intimately acquainted with compassion typically equate it with self-pity—which it is not. Compassion does not pity, it understands. Sometimes self-pity is a perfectly valid response—to a painful loss, for example. But most people recognize that chronic self-pity depletes their vitality. In stark contrast, compassion mobilizes energy and is a wellspring of courage.

Both self-affirmation and compassion are built up when you make both large and small decisions that promote your best interests. An effective way to recognize your capacity for positive action is to remember choices you’ve made in the past that were clearly good for you. Trust the memories that spontaneously come to mind. Perhaps you’ll recall committing yourself to a relationship in spite of the risks or leaving one that was undermining you. Other possibilities might include moving to a new location (not because you were running away, but because you always wanted to do it), quitting a dead-end job or embarking on a new career, confronting an addiction or destructive habit, making health-promoting choices about food or exercise, developing a new skill, or doing something that felt right for you despite disparaging comments from family or friends.

Focus on how you reached those decisions. Did you realize at the time that you were acting in your own best interests, or did that become apparent later? Were your choices spontaneous, or did you struggle with them for a time? How did you deal with your misgivings and fears?

As important as these dramatic turning points are, the cultivation of self-affirmation as a way of life depends on the cumulative effect of smaller decisions made on a daily basis. Such choices may seem so insignificant at the time that you hardly notice them. Yet their impact can be enormous. Think back over the last two weeks. How many instances can you recall, no matter how small, in which you acted in ways that were self-validating? Such instances might have involved expressing feelings or opinions that you would normally keep to yourself, assertively asking for what you wanted, saying “no” in spite of pressure to acquiesce, or taking care of yourself in other ways.

You may wonder if being self-affirming on a regular basis might make you demanding, pompous, blind to your own faults and imperfections, or less sensitive to others’ feelings. In my experience, increases in self-affirmation actually have the opposite effect—they make us less self-centered and more cooperative and empathic.

What does self-affirmation have to do with erotic transitions? Just about everything! With few exceptions, blockages and distortions of your deepest inclinations lie at the root of self-defeating turn-ons. The alternative is to listen carefully for the guidance that comes only from within.

STEP 3:

NAVIGATE THE GRAY ZONE

Once a significant transition is under way, it’s only a matter of time until you enter a period of awkward uncertainty when you’re no longer where you’ve been, but you haven’t arrived at where you’re going. Welcome to the gray zone, which, of course, is not a location but a state of mind distinguished by a distressing absence of clear pathways and landmarks. For a time you feel as though you’re wandering aimlessly, disoriented, lost without a clue about how to regain your bearings.

The more important and challenging the changes you seek, the more prolonged will be your stay in the gray zone. For some, being in the gray zone feels like standing at the edge of an abyss. But if you can tolerate its ambiguities, the gray zone holds unparalleled opportunities for self-discovery. Gradually, you will notice that the gray zone is not at all the featureless desert it first appears to be. It’s more like a blank canvas on which you can experiment with new shapes and colors.

STUMBLING INTO THE GRAY ZONE

Sometimes the first hint that you are entering the gray zone is a realization that partners, situations, or fantasies that have reliably turned you on in the past are losing their allure. If you aren’t prepared for the surprises that await you in the gray zone you might misinterpret your waning interest as a sign of trouble rather than a harbinger of positive change. Men find it especially difficult to handle this temporary reduction in desire because it is usually reflected in less reliable, softer, or nonexistent erections.

When old turn-ons begin to lose their effectiveness, some people embark on a search for more intense forms of stimulation to prove to themselves that everything still works. Unfortunately, their first impulse is often to repeat—with even more single-minded determination—the very patterns that are losing their grip. One man could no longer ignore the fact that he wasn’t responding to his porn collection featuring leather-clad dominatrixes. So he went on a frantic search for new porn with even more exaggerated images of dominance and submission. Only later did he realize that these purchases were completely useless because his eroticism was evolving away from the imagery of power and toward—well, he didn’t know yet. But once he accepted the fact that his old arousal patterns were crumbling to make room for something new, yet undefined, he was better able to accept the flux and uncertainty of the gray zone.

Maggie Revisited: Turning away from longing

When Maggie entered therapy to deal with the loss of her relationship with a married man, she had no idea her eroticism was on the brink of a radical shift. She fully expected her attractions to remain essentially the same. She just wanted to make them work better. But once she realized that she was “hooked on longing,” that her greatest turn-ons involved “almost being loved,” and that fantasies of fulfillment excited her more than the real thing, she was understandably perplexed.

“What do you expect me to do now?” she demanded in exasperation. “I don’t even know which men turn me on anymore. I thought therapy was supposed to make me less confused. I’ve never been so unsure!” Maggie had stumbled into the gray zone and didn’t want to be there. But out of necessity she rallied her considerable inner resources to meet its challenges.

She was amazed by a curious phenomenon she named the “dual response.” “When I see the kind of man who has always attracted me,” she explained, “immediately I’m as fascinated as ever. I can spot these guys across a room. But now the moment they grab my attention, something inside me snaps and I feel myself turn off and I think, ‘Yuck! What a jerk!’” This contradictory response is typical in the gray zone. Maggie ultimately discovered that by selecting ambivalent men to pursue she had distracted herself from the fact that she was as ambivalent about intimacy as her lovers. “At least I used to enjoy the chase,” she said. “Now all I see is the same old story with the same shitty ending: poor little Maggie chasing after crumbs. I’ve had it! It’s too damn humiliating.”

Maggie’s most important decision was to solidify a policy of self-respect. Her manifesto became: I don’t want to be with anybody who doesn’t want to be with me. “I don’t care if I ever fall in love again,” she insisted. “If he doesn’t love me back, I’m not interested.” For months she dated only sporadically, gingerly sampling different kinds of men and conducting experiments that had been impossible when she was focused on pursuit. Through it all her policy held firm. She had broken the spell of the chase.

CHOOSING A MORATORIUM

There are times when it is advantageous to create a gray zone consciously and deliberately by voluntarily abstaining from your usual practices for a period of time—sometimes specified, sometimes not. Freely choosing not to do what you normally do can help you in two ways. First, by stepping back from automatic behaviors you gain a fresh perspective on what your eroticism is trying to accomplish or express. Second, by detaching from well-worn habits you open up space in your erotic landscape for experimentation and self-observation.

Unless it is imperative that you stop what you’re doing right away because of life-threatening consequences (risking arrest, injury to another person, or exposure to AIDS, for example), it’s pointless to attempt such a moratorium until an internal consensus is reached. Until then, the most effective approach is to decide to continue doing whatever you feel compelled to do, and to do it mindfully. Sometimes even a modest increase in consciousness brings people face to face with how their behavior actually makes them feel. For instance, those who are sexually driven often become so “spaced out” that they have little or no awareness of what they’re feeling before and during a compulsive episode. Consciousness typically reveals a host of unpleasant emotions wrapped up in the turn-on, most commonly fear, hatred, sadness, and shame. As these unpleasant feelings are recognized, they serve as push motivators, prompting the person to pause and consider a new path.

TAPPING THE POWER OF IMAGINATION

Your journey through the gray zone will yield maximum rewards if you use your mind’s eye to perceive possibilities that don’t yet fully exist. This may be difficult if you’ve learned to trust only what you can verify through reason or the senses. Great discoveries—whether in science, the arts, or personal life—require imaginative leaps in which the discoverer moves beyond typical modes of thought and perception.

With a little practice and patience almost anyone can learn to apply the gifts of imagination to erotic transitions. There are two requirements. First, clear some time to imagine. Second, resist the urge to criticize the products of your imagination prematurely. And remember, when judged by normal standards of productivity, imaginative pursuits look suspiciously like play. Those who think they must always be accomplishing something are often reluctant to let their imaginations roam freely.

Try this experiment. When you’re not preoccupied or in a hurry (is there such a time?) find a quiet, private place to sit or recline. Allow your breathing to slow as it deepens. With your eyes closed, scan your body from head to toe, allowing each group of muscles to relax. As you inhale, notice sensations of calm and warmth flowing through your nostrils, filling your lungs, and radiating throughout your entire body. Each time you exhale, let tension and worry melt away. Don’t be concerned if you’re easily distracted. Each time your mind wanders, gently bring it back to the soothing rhythm of your breath.

Now recall an especially positive and fulfilling sexual experience. Maybe you’ll revisit one of the peaks you’ve remembered before, or perhaps a different memory will surface. Remind yourself that the most satisfying experiences are not necessarily the wildest. Savor the feeling of actually being fulfilled. Linger over the simple details that brought you pleasure. Reexperience how you felt about yourself during and afterward. Vividly reliving experiences of sexual satisfaction helps clarify your goals and strengthens your motivations.

You can also use your imagination to visualize what might happen if you were to let your eroticism venture off in a new direction. Don’t worry if your images are fuzzy or keep changing. By its very nature the imagination plays with possibilities. If at first you draw a blank when it comes to your erotic future, don’t be concerned. In time your imagination will conjure up pleasurable fragments. Be aware, however, that the moment you try to freeze one image to the exclusion of others, you halt the imaginative process.

Long before Maggie adopted her policy of turning away from the sorts of men she once pursued, she visualized the implications of such a decision in her mind. Her initial images were of being stuck with one of the “normal” men who had always bored her. But as she recognized how frustrating it was to be perpetually in a state of longing she grew increasingly fascinated by the image of being loved without reservation, not by a boring man but by an available one. She couldn’t help noticing that whenever she had grasped for love that dangled just beyond her reach she had become highly excited but also frantic. But when she pictured herself withdrawing from the chase and letting someone approach her, she felt calm and self-assured.

Whether you stumble unexpectedly into the gray zone or place yourself there by deliberately stepping away from well-worn but unsatisfying behaviors, your journey is destined to be unsettling. Expect to feel lost and alone for a time. Chances are you’ll also be frustrated as you grope for answers that rarely come easily. Why put yourself through something so uncomfortable? Besides the fact that you may not have a choice, the gray zone is a powerful impetus for change. It is an opportunity to confront yourself as you never have done before—and to emerge stronger, with a piercing new clarity about what you must do for yourself and how it can be done.

STEP 4:

ACKNOWLEDGE AND MOURN YOUR LOSSES

All growth, no matter how desirable or eagerly sought, involves loss. As outgrown habits fall away, you naturally miss their comfort and familiarity. Every troublesome turn-on has fulfilled crucial functions along the way—or it never would have developed in the first place. Even when it hurts you, it cannot easily be tossed aside.

As the changes you imagine find a place in your life, don’t be surprised if emotions associated with grief and loss—sadness, loneliness, emptiness, anger, or guilt—are a part of the experience. Try not to resist, downplay, or deny these feelings; they are essential for healing. Grieving is the way through the pain of loss.

Because thrilling turn-ons are often fueled by conflict and ambivalence, they are frequently the most difficult to change, particularly if painful or traumatic experiences are woven into them. As we become aware of how our turn-ons are linked to unpleasant memories, we can begin exploring more fulfilling, less conflicted erotic styles. Unfortunately, these more comfortable expressions of eros typically involve a distinct reduction in sexual intensity, an intensity that will be sorely missed.

Ryan Revisited: Excitement lost

Ever since his father caught him playing with himself, Ryan had been at war with his sexual urges, a battle that had not only taken an enormous emotional toll but had also provided an inexhaustible source of risqué fascination. When he fell in love with Janet he was forced to face the fact that love and lust had long since become so thoroughly incompatible that he was unable to generate sufficient excitement with Janet to trigger an orgasm.

Ryan’s therapy progressed rapidly. He discovered that struggle was the fuel for his compulsive urges and that calling himself a “sex addict” only amplified his conflict. Gradually, because he loved Janet, he freely chose to step away from his “affair” with porn shops and phone sex, concentrating instead on the novel experience of sex with a woman he cared about. He and Janet experimented more freely with sensuality and affection, and both enjoyed a deepening closeness.

In response to this progress Ryan fell into depression. “It makes no sense,” he lamented. “Everything is going so well, yet a cloud follows me wherever I go. Everything is flat and colorless.” As much as Ryan appreciated his relationship with Janet, he also missed the passion of the raunchy sex he had spent a lifetime both fighting and pursuing, the sex that he had always counted on to distract him from unpleasant emotions.

Although reluctant to admit it, Ryan was in mourning. As it does for so many people in his situation, Ryan’s growth stalled until he granted himself permission to recognize the depth of his attachment to forbidden lust. He needed to respect the lost rewards—not just the suffering—of the eroticism he was leaving behind.

THE PAIN OF LOST HOPES

As you’ve frequently seen, problematic sexual patterns evolve to compensate for unmet needs or to soothe unhealed psychic wounds. One reason troublesome turn-ons are so tenacious is that they express an enduring hope that all can be made well and whole. To some degree, sexual reenactments shield us from the distressing reality that in emotional life what is lost can never be regained.

When you alter an unfulfilling erotic pattern, you might begin to feel, more intensely than ever before, the emotional pain that your CET was originally designed to soothe. Understandably, you might shrink from that sting, choosing instead to endure the dull ache of the status quo. Yet, paradoxically, when you allow yourself to feel your pain fully, you free yourself from it. It is the acceptance, not the denial, of hurt that heals us.

STEP 5:

COME TO YOUR SENSES

Difficult turn-ons come in as many varieties as fulfilling ones. Yet one feature is shared by virtually all problematic erotic scenarios: they ultimately disrupt the relationship between a person and his or her body. The vast majority of troublesome turn-ons are rooted in antisexual messages that contaminate opportunities for children and adolescents to express playful curiosity about their own and others’ bodies.

The fact that most people develop ways to express their sexuality in spite of antisexual training is a tribute to the resiliency of the human spirit. Yet many continue to honor early restrictions by subconsciously imposing limits on the amount or types of pleasure they allow themselves to give and receive. One pleasure-limiting strategy—so widespread that it is considered normal—involves focusing erotic attention primarily or exclusively on the genitals and other erogenous zones, relegating the sensuous capacities of the rest of the body to “foreplay.”

In the last chapter you saw how the good feelings of arousal can fuse together with painful or traumatic experiences, producing either intractable inhibitions or obsessions. Men and women who were abused as children or assaulted as adults may find that even simple touches are so thoroughly associated with trauma that they can’t be enjoyed. Others become trapped in ultra-focused, ritualized patterns of behavior or fantasy or both that are long on intensity but short on pleasure. It’s not unusual for those caught up in the pleasure-pain bind, particularly men, to seek out maximum genital stimulation and orgasmic intensity, with little or no interest in sensuality or affection.

One of the most effective ways to facilitate erotic healing is to rediscover the sensuous capacities of your entire body. The body has a wisdom that transcends logic. By “coming to your senses” you begin to reconnect with the first source of all positive eroticism.

TOUCHING FOR PLEASURE

One of the best ways to reconnect with your sensuality is to use what sex therapists call sensate focus. Originally designed as a set of experiential exercises to help people with sexual dysfunctions calm debilitating performance pressures, sensate focus is the most enduring contribution of sex therapy pioneers Masters and Johnson. Directing your attention to the concrete world of your senses can be particularly helpful when you’re in the gray zone, unsure of what to do next. Whether you’re trying to resolve a sexual problem or expand your repertoire for pleasure, you can benefit from experimenting with sensate focus by yourself, with a partner, or both.

I recommend you begin by setting aside time for self-pleasuring. If masturbation is already part of your sexual repertoire, consider expanding your enjoyment by touching your whole body—not just your genitals. It helps to create a conducive atmosphere, perhaps with the help of a hot bath, a crackling fire, or music. You may feel silly at first, but a great deal can be learned by unhurriedly gazing at your naked body in the mirror. Pause to appreciate the parts of your body you like best. But there’s no need to pretend if, like everyone else, you also have features you wish were different.

Next sit or recline comfortably and slowly touch yourself everywhere. Notice which places feel good as well as which don’t. Adopt a playful, experimental attitude, touching yourself with varying rhythms and pressures. Try using a lotion or oil (safflower, peanut, or coconut oils work well) to add a silky feel. If it interests you, use a vibrator. See if you can discover something new about your body, an unexpected source of pleasure or a way of touching you’ve never realized could feel so good. If you want to touch your genitals, do it a little differently from the usual way.

Pay special attention to your breathing. Deep, easy breaths allow pleasurable sensations to flow; shallow ones restrict them. If you become aroused—which certainly isn’t necessary—notice how your muscles gradually tense. See what happens if you deliberately let your muscles relax as arousal builds. Deep breathing and muscle relaxation are the two most direct ways to slow down and stretch out your enjoyment. If you’re not used to this leisurely, nongoal-oriented approach to self-pleasuring, you may feel a bit awkward until you try it several times.

Men who want to “last longer,” to be able to enjoy more sexual stimulation before ejaculating, can benefit tremendously from experimenting with this slower approach to masturbation. The key is to discover that by taking deep breaths, allowing your pelvic muscles to relax, and temporarily reducing the speed and intensity of the stimulation, you can influence how quickly or slowly your body responds. Keep in mind that these simple techniques are effective only before you reach the point when ejaculation becomes inevitable. Once you learn to prolong your responses in private, you can then use similar techniques with a partner.3

Fantasies are often a natural part of self-pleasuring. In fact, during masturbation people typically explore their fantasies more freely than at any other time. Some fantasies contain important clues about what might turn you on with a real-life partner, whereas others are enjoyable only in the realm of imagination and have nothing to do with reality. Either way, see what it’s like to let your fantasies roam freely during self-pleasuring.

If you have a tendency to become so caught up in fantasies that they distract you from your body, you can benefit by focusing as much as possible on physical sensations. There are people who are so thoroughly attached to specific fantasies that they believe they can’t become aroused or have orgasms without them. For such people sex is a “head trip” rather than a sensuous experience. If this is true for you, it’s a losing proposition to fight your fantasies. See what it’s like, though, to gently direct your attention to your own touch, even if the intensity is less than you’re used to.

Sharing sensate focus with a partner, of course, opens up additional opportunities and challenges. On the plus side, touch usually feels even better when it is provided by another person. And the visual and tactile appreciation of someone attractive brings additional sensuous delights. The difficult part is that the presence of a partner, with his or her own preferences, necessitates some form of communication.

I suggest you begin by taking turns massaging and being massaged. Distinguishing the pleasures of giving and receiving helps to identify how you feel about each experience—which may be quite different. It’s important to create an inviting atmosphere just as you did for self-touching. Make a point of spending plenty of relaxed time together before you begin, perhaps sharing an intimate conversation over dinner. Be sure the room is warm. Also, because it can be fatiguing to maintain your balance while massaging someone on the relatively soft surface of even the firmest mattress, it’s better to lay a thick blanket on the floor.

Decide who will touch first. Using a massage oil, begin caressing your partner with smooth, slow strokes, ranging from soft to deep. Ask for feedback on which feels best. Encourage your partner to alert you immediately if anything hurts or tickles. Take your time and massage all areas of your partner’s body that feel comfortable for both of you. Men and women who have been sexually abused or assaulted will probably need to take it very slowly, learning how to feel safe at each step. If one or both of you has been worrying about a sexual dysfunction, your comfort level will be much higher if you agree ahead of time to leave out areas that may trigger anxieties, most likely the genitals. Couples who have never done this kind of touching should begin with small steps, maybe just a back rub or a foot massage. Notice how it feels to be the toucher. Do you receive pleasure from giving? Or are you bored or busy evaluating how well you’re doing?

After a break, switch roles and see how it feels to be on the receiving end. It’s helpful if your partner asks what you like, but practice volunteering information by making pleasurable sounds when something feels good or requesting to be touched more firmly or gently, faster or slower, or in a different location. Relatively few people are easily proficient at this kind of direct communication. Even long-term couples find it difficult. Recognizing this fact can help you avoid yet another source of pressure: the need to be a perfect communicator.

Some couples complain that these experiments are too clinical. Anything new feels unnatural at first, but if you are willing to stay with it, soon self-consciousness will give way to playful fun. Exchanging pleasure-oriented massage is not only enjoyable, it’s also a terrific way of learning about each other’s preferences. No special training in massage is necessary. If, however, you wish to learn more about how to use the magic of touch to enhance your pleasure or to help solve problems, excellent books are available to guide you.4

CONFRONTING PLEASURE ANXIETY

It’s common knowledge that too much anxiety inhibits pleasure. What isn’t so well understood is that too much pleasure sometimes provokes anxiety. It should come as no surprise that children who are taught to mistrust their bodies grow up feeling uneasy with sensuous pleasures. Similarly, those whose bodies have been violated through severe corporal punishment or sexual abuse learn to think of their bodies as sources of pain rather than enjoyment. Others believe it’s “selfish” to receive too much pleasure and therefore deflect touch away from themselves. Men and women who are self-conscious about their physical imperfections—and such feelings are difficult to avoid given the constant parade of perfect bodies in the mass media—may feel they’re not sufficiently attractive to deserve extensive pleasuring or that no one could genuinely enjoy touching them.

Pleasure anxiety causes people to “numb out” because blunted sensations are easier to tolerate. One common strategy is to develop a rigid armor of tense muscles that act as an invisible shield against both pleasure and pain. Before anything can be done about pleasure anxiety it must be acknowledged with compassion and understanding. Once recognized, however, it’s crucial to create opportunities to stop avoiding pleasure and learn how to relax and receive it. This is no small feat for those who are wary of the body’s delights. But without a comfortable relationship with one’s sensuality, the erotic adventure is ultimately doomed to be unfulfilling.

Nancy and Burt Revisited: Touching for self-discovery

When you met Nancy and Burt in Chapter 6 they had both stopped drinking but their sex life was in shambles. Nancy had realized that without alcohol she was too inhibited to act the sexual adventurer role she had perfected during the freewheeling 1970s. Instead a resurgence of guilt from her strict Catholic upbringing was turning her off completely. And Burt was wrestling with an old belief that he was boring and unattractive.

Having reached a point where they actively avoided all touch except friendly hugs and kisses for fear that they would repeat the cycle of expectation, rejection, and frustration, they were ideal candidates for sensate focus. They both liked the idea of pressure-free touching and eagerly made their first date for a nonsexual massage. Even though they both said they enjoyed the massage, neither showed much interest in trying it again. Week after week other responsibilities always took precedence. If anything, they touched less often than before.

People avoid touching experiments for all kinds of reasons, including a fear of raising expectations, the embarrassment of not getting turned on, the concern that one partner may feel more sexual than the other, or worries about not doing it right, to name just a few. None of these seemed to explain Nancy and Burt’s avoidance. It was Nancy who first hinted at the truth. “I know this is supposed to be pleasurable,” she said, “but I just can’t seem to relax.”

“Me neither,” chimed in Burt. “You’d think I was a teenager on my first date. Back then I might have been nervous as hell, but at least I was determined to get inside her pants. I have no idea how it feels to touch for no reason other than it feels good.”

When I asked them whether they felt more comfortable giving or receiving touch, both answered in unison, “Giving.” Once their uneasiness about receiving became an open subject, they were willing to continue experimenting, especially when I encouraged them to pay close attention to what they were thinking and feeling. Like most people, they were under the impression that sensate focus is only successful for those who are able to ignore or suppress “mental chatter” and concentrate solely on physical sensations. Although it can be wonderful to do just that, watching random thoughts, feelings, and memories come and go is harmless, completely normal, and sometimes very instructive.

Nancy observed what professional body therapists know: the most potent messages, memories, and emotions from childhood aren’t simply stored in deep recesses of the brain, but are somehow etched directly into the tissues of the body. Once she began paying attention, she couldn’t help noticing that the better Burt’s touches felt, the more tense and guilty she became. “It doesn’t matter what I think,” she mused, “my body is convinced that pleasure is wrong, wrong, wrong!”—shocking words from a former sexual liberationist.

Nancy’s insights emboldened Burt to observe himself the next time Nancy pleasured him. “When Nancy was stroking my inner thighs and balls last week,” Burt explained, “I wanted to push her away even though it felt terrific. I guess I don’t like being in the spotlight.” By consciously resisting his urge to flee from the receptive position, he saw how he had learned to compensate for feeling unattractive by focusing on stimulating his lovers. Burt wasn’t guilty about pleasure the way Nancy was. He just couldn’t believe that anyone could genuinely want him to lie back and do nothing but enjoy. Burt also acknowledged that, like many men, he had trouble with the passivity of receiving pleasure. “Guys are supposed to be doing something,” he said. “I feel like I’m slacking off on the job.”

Nancy and Burt’s inhibitions about pleasure were so thoroughly ingrained that only careful, courageous self-observation uncovered them. They took the risk of disclosing difficult, embarrassing feelings and attitudes they had concealed even from themselves. Gradually, the naughty thrills that once defined and limited their eroticism yielded to a pleasure-based approach. Sometimes they missed the heart-pounding intensity of overcoming so many obstacles on the road to passion. But the deepening bond between them brought a whole new dimension to their lovemaking.

As you can see, sensuous touch is a potent tool for healing, self-awareness, and simple enjoyment. It can also help you recognize hidden anxieties about pleasure, anxieties that aren’t pleasant to confront but necessary if your eroticism is to evolve. Touch isn’t the only way to come to your senses. Dancing, stretching, walking, or other forms of exercise offer opportunities to rediscover the joy of spontaneous movement and the vitality and strength that flow from it. Although these activities may seem far removed from sex, they all reconnect you with your body—the fountain of eros.

STEP 6:

RISK THE UNFAMILIAR

Therapists and clients alike often share a mistaken belief that gaining insight into the hidden roots of troublesome symptoms leads directly to more fulfilling behaviors. Although this notion holds an obvious appeal, it can also blind us to the complex realities of growth. Rarely is change automatic, no matter how insightful you are, especially when you’re grappling with long-established patterns.

I’m not suggesting that self-awareness is useless, just that it promotes change only insofar as it emboldens you to try something out of the ordinary. Those who insist on spontaneous, “natural” change inevitably stick to the status quo—the only thing that truly comes naturally. Insights call your attention to the kinds of risks that are necessary. Then, if you can rise to the occasion, your courageous, unnatural choices will yield far more results than any amount of armchair analysis.

RECOGNIZING AND SEIZING OPPORTUNITIES

There’s a Buddhist saying: When the student is ready, the teacher will come. Sometimes that teacher is another person—a mentor, guide, or role model who challenges you to stretch your limits, while instilling confidence that you can to it. More often, life itself is the teacher, but only for those ready and able to follow an uncharted course. Whether we notice or not, life regularly invites us to step outside the constraints imposed by our habits. Unfortunately, most invitations go unanswered.

Whenever you make a mindful choice to respond differently than usual, combining awareness with concrete action, your goals and motivations make a leap toward actualization. Your decisions need not be dramatic to be effective. Even the smallest changes, when consciously chosen, make successive ones increasingly tangible and gratifying.

Carlos revisited: Allowing connection

Caught on the horns of a self-hating dilemma, Carlos, the unhappy voyeur you met in the last chapter, had learned in early adolescence to use inferiority as an aphrodisiac. Once he confronted how his CET magnetically drew him to idealized but unreachable men and dangerous situations, he faced many choices. For him, a major step was to disengage from locker room spying and venture into gay sex clubs, a world of consensual sex that sometimes leads to dates and occasionally even relationships.

Some people may have trouble seeing how engaging in casual sex could be a sign of growth, but for Carlos it was. He had a strict safe sex policy so he could explore his sexuality without life-threatening consequences. I remember his delight at spending hours with men who were as enthusiastic as he. Of course, the men whom he considered most perfectly masculine and frustrat-ingly aloof invariably attracted him most. But there were other men who pursued him, a totally new experience he didn’t know how to handle. Though it wasn’t easy, he coaxed himself into not turning away. He knew that learning to accept positive attention was the only alternative to the searing pain of constant rejection.

Whenever Carlos was in emotional turmoil, however, his masturbation fantasies reverted to voyeurism. He noticed that his self-esteem took a nose-dive as he worshipped the objects of his desire. As a result of this awareness, he began to wonder what would happen if he were to celebrate his appreciation of the male form, to feel enriched by a man’s beauty rather than demeaned by it. This became the central question of his therapy and his life.

Gradually, Carlos experimented—in both fantasy and behavior—with positioning himself more favorably in relation to men he admired. His initial discovery probably won’t surprise you: inferiority was sexier. Equality, however, was infinitely more gratifying. The only people who can fully comprehend this distinction are those who know firsthand the intensity of eroticized self-hatred.

Carlos eventually began dating, cultivated the necessary social skills, and learned to avoid interpreting each man’s reaction to him as a referendum on his worth. Eventually, he moved in with a guy who was handsome and affectionate but not as irresistible as the fantasy guys he continued to stalk in his imagination. This man wanted to love him, and Carlos’s greatest achievement was the decision to receive that affection.

If you’re pursuing any kind of erotic transition, large or small, I have a prediction. One day you’ll look back on how far you’ve come and wonder how you did it. I doubt that you’ll recall one pivotal turning point, except perhaps the decision to begin. Like Carlos, most likely you’ll recall a series of unfamiliar and awkward experiments, opportunities seized in spite of—or because of—the risks. Through these experiments you turn the promise of change into a reality.

STEP 7:

INTEGRATE YOUR DISCOVERIES

If alternative erotic styles are to be more than passing experiments, they must become woven into the fabric of your everyday life. For a lucky few, this integration occurs with relative ease. Especially when modifications are readily satisfying and don’t seriously conflict with older patterns, merely repeating pleasurable new behaviors may be sufficient to establish them.

For most people, however, it’s not that easy. I’ve observed dozens of men and women attempt new forms of erotic expression, only to revert to less fulfilling but more predictable ways of being. They found that the most daunting aspect of an erotic transition wasn’t trying new behaviors but making these changes stick. Unless you learn how to do this, your discoveries from the previous steps may, in the end, prove to be futile.

Few if any of us follow an uninterrupted path toward our goals. More commonly, we make headway until we come up against some internal or external blockage that tests our motivation. At such moments we may feel as if we’re going backward. These setbacks are among the most common impediments to our development. But it’s not the setbacks themselves that hinder growth. Far more important is how we respond to them. Some people quickly become demoralized, interpret their setbacks as signs of weakness, or perhaps even abandon their goals.

When you encounter a setback, I encourage you to view it not as a failure but as an opportunity to integrate change at a deeper level where it’s more likely to take root and flourish. Sometimes this is simply a matter of recognizing reversals as thoroughly human and inevitable, and deciding to persist in spite of them—with as little self-criticism as possible. But I’ve learned from my clients that persistent setbacks serious enough to undermine positive change are, more often than not, signs that a person must wrestle with one or both of two crucial questions: (1) What is the relationship between the changes I seek and how I perceive myself? and (2) How do I deal with my old turn-ons as I practice new ones?

IDENTITY AND CHANGE

If you’re determined to bring about meaningful changes in your erotic life, don’t make the mistake of thinking of them in isolation. By its very nature eroticism interacts with your entire personality. Modifying it, even in seemingly small ways, often has unexpected implications. Some people aren’t prepared for these ramifications and thus flee from change at the very moment when it’s within easiest reach.

Identity—including your core beliefs—provides you with a sense of stability. Modifying how you act or perceive yourself may threaten that stability, so much so that you begin to question who you are. Most people find this ambiguity difficult to tolerate. Consequently, during periods of transition you may feel an urge to cling to the self-image you know best—even if this means slowing or abandoning your progress. The alternative is to take up the challenge of expanding or reshaping how you see yourself.

It’s fascinating to observe the seemingly contradictory effects that growing has on identity. On the one hand, to grow is to become increasingly aware of and comfortable with your individuality. On the other hand, growing forces you to stretch in order to make room for previously rejected or newly discovered aspects of yourself. This enlargement of self is a hallmark of psychological development. Usually, however, it’s also quite painful.

Regina revisited: Making room for love

Once Regina broke the stranglehold of silence about the sexual abuse inflicted on her by her stepfather, she was able to see that her need’ to seduce men had little to do with pleasure. She seduced to reassure herself that she was in control and to reaffirm the conviction that her value was as a sexual object. You may recall that when she instigated a crisis by slashing her wrists, she had recently begun dating a man who didn’t fit the mold of the cold, aloof ones she usually chose.

No matter how much she expected him to use and abandon her, he refused. Instead he genuinely enjoyed her company, listened to her eagerly, held and caressed her passionately—and all without pushing for intercourse, which he sensed made her uncomfortable. One of the last mysteries Regina confronted in therapy was the irrational truth that this man’s love had somehow pushed her toward self-destruction. The jagged cuts on her arms were symbolic reminders that she couldn’t tolerate affection without suffering.

According to her long-standing core beliefs, Regina deserved exploitation and rejection. She was also trying to strengthen a more recent—but much weaker—belief that it was her birthright to be treated with respect. An inner battle was raging. Each time she accepted nurturance and love from Bob, she had to believe she was worthy of it. Some days that challenge was overwhelming and she would run away. “If he would just use me,” she explained with extraordinary insight, “I would know who I am. It hurts to be loved!” Her pain was caused by the stretching of her identity.

To help you solidify positive changes, make a point of recognizing how each one coincides or conflicts with your self-image. Don’t be surprised if you can’t determine this easily. Live with new behaviors and ways of thinking about yourself for a while and notice how readily you become comfortable with them. If you find yourself avoiding the very things you think you want, consider this an indicator that your current identity is incompatible with the direction of your growth. It takes considerable courage to initiate the necessary shift in identity, but the process is quite straightforward if you decide to pursue it.

The most important thing is to continue exploring the changes you’re having trouble integrating. But instead of avoiding discomfort when it arises, let yourself feel it, and eventually you’ll learn about its source. Had Regina run away from her kind boyfriend as she often wanted to, she would never have confronted her internal reluctance to receive love. Only after she saw how her self-image was restraining her could she consciously begin to modify it.

How can identity be modified? Unfortunately, no easy answers exist. But I’m convinced that it’s much simpler to add new self-perceptions to your identity than it is to banish old ones. In fact, if you struggle too fiercely with established beliefs, they will likely grow stronger. Rather than trying to get rid of or suppress self-defeating beliefs, you’ll do much better if you concentrate on bolstering emerging beliefs that foster choice and self-affirmation. Sure you’ll experience some inner conflict, maybe a lot. But as your new beliefs grow sufficiently strong, they will show you how to deal effectively with the old ones and reduce their damaging effects.

It also helps if you highlight aspects of your current identity that you can embrace wholeheartedly. Your identity is multidimensional and undoubtedly includes many features you can feel good about. Regina, for example, disliked her tendency to act as if she deserved mistreatment. At the same time, she appreciated her boldness, her willingness to take chances and, if necessary, to break the rules. She had always been a fighter, a characteristic that had helped her survive despite her antiself inclinations.

Recognizing, respecting, and expressing one’s positive qualities stimulates an enlargement of identity and increases self-esteem. Because identity unfolds gradually as you grow up, altering it requires time and patience. Making room in your self-image for new potentials is a labor of love. Only those who decide they are worthy of that love can mobilize the necessary persistence. Then the expansion of identity becomes profoundly uplifting. One of the greatest joys comes from perceiving something old and familiar in a whole new light.

WHAT BECOMES OF TROUBLESOME TURN-ONS?

Almost as challenging as expanding one’s identity is figuring out what to do with old sexual scripts as new ones take hold. In a logical world, problematic scenarios would quickly lose their appeal in the face of more fulfilling ones. In actual practice, most men and women who successfully create more gratifying turn-ons make a similar discovery about their erotic repertoires as they do about their identities: it’s much easier to cultivate new sources of arousal than to cast aside old ones. This is the primary reason that I suggested in Step 1 to focus your goals on what you want rather than what you don’t want.

Although it may go against common sense, integrating erotic changes normally doesn’t involve obliterating problematic turn-ons altogether but rather finding a harmless place for them in an expanding, multidimensional self. Is such a feat realistic, particularly for those whose CETs have compelled them to reenact self-defeating scenarios? I’m convinced that it is. Needless to say, the ability to integrate once-destructive turn-ons into a self-affirming identity rarely develops easily. But unquestionably it does happen.

Ryan, the “prisoner of prohibition” who had spent most of his life struggling with his fascination with sleazy women, is a good example. With determination and courage he learned to enjoy warm, affectionate sex with his girlfriend, Janet. He even mourned the loss of the heart-pounding excitation his old activities once produced. Yet raunchy images continued to run through his fantasies no matter how much he tried to control them. For a time he couldn’t resist declaring himself a failure.

It was obvious he had truly reached his goals only when he learned to accept—and enjoy—these fantasies, without reactivating the inner battle that had made him miserable for so long, and without sinking into shame or self-reproach. Eventually, he even went so far as to use old naughty feelings, accompanied by a wisp of guilt, as harmless aphrodisiacs. Ryan’s battle didn’t end with the vanquishing of his old turn-ons as he once assumed it would. Instead his ultimate success stemmed from a transformation in how he used them.

Most people I’ve known who have successfully resolved troublesome turn-ons have been similar to Ryan. They gradually discovered that it wasn’t their sexual scripts per se that had hurt them. The real problem was how they had learned to use their CETs against themselves. Once they stopped doing that—the most far-reaching change of all—they went on to develop more relaxed attitudes toward erotic material that was once deadly serious. By building an identity founded on self-respect, they used their imaginations to enjoy scenarios similar to those that once tormented them but without taking any of their detrimental aspects to heart.

PUTTING THE SEVEN STEPS TO WORK

Erotic transitions are as multifaceted as eroticism itself—full of detours and surprises. Try not to think of these steps as instructions to be followed like a recipe. To receive maximum benefit, approach them with a spirit of flexibility and creativity.

Concentrate first on the steps that capture your attention or evoke strong emotions. It is wise to consider any strong response, positive or negative, as a signal to look closely—if not now, then later. Don’t worry about why you’re drawn to one step or another. The key is to establish a high degree of personal involvement, and the best way to do that is to follow your natural inclinations. Later you can always take a second look at the steps that didn’t particularly interest you the first time through. They may gradually take on new meaning as you grow.

These steps are synergistic—their combined effect is much more powerful than the effect of any single step. As you become engaged in any step, your involvement will have a ripple effect. Lessons learned from one step easily carry over to all the others. Also keep in mind that these are not the types of steps that require you to complete one before moving on to the next. Each step launches an odyssey that is never completely finished.

A WORD ABOUT AA AND THE TWELVE STEPS

If you’re currently in a twelve-step program you may be concerned about whether the seven steps described in this chapter might conflict with your recovery. I’ve worked with dozens of people who have used the seven steps as beneficial supplements to the twelve steps of Alcoholics Anonymous or similar self-help groups. Many people in recovery have no idea how to recognize and cope with the erotic dimensions of sobriety, a topic rarely discussed at meetings. The seven steps are useful because they’re specifically designed to promote sexual growth and healing.

If you’re benefiting from a twelve-step program for a chemical addiction and also struggling with self-defeating sexual behaviors, you might wonder if programs such as Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous (SLAA), Sexual Compulsives Anonymous (SCA), or Sexaholics Anonymous (SA) might help. Although their social support and emphasis on spiritual renewal can be valuable, the disappointing fact is that these groups are among the least successful of all twelve-step programs. Many participants are discouraged by the unending litany of “slips” and by how few people have found comfort with their sexuality—so different from AA, where role models for long-term recovery are plentiful. Without becoming disillusioned about the wisdom of the twelve steps, it’s important to understand why an approach that’s so helpful for substance addiction may not be the solution for your erotic conflicts.

Erotic problems often involve compulsive repetitions and obviously have many features in common with chemical addictions, most notably an inability to modify behaviors despite negative consequences. Whereas recovering addicts completely sever the relationship with their drug of choice in order to find themselves, a person driven by sexual impulses can never sever the relationship with his or her eroticism.

The focus on abstinence that is appropriate for severe chemical addictions usually ends up making matters worse when applied to compulsive sex or obsessive “love.” This is not to say that abstinence can’t be a valuable tool as part of the process of erotic change. In Step 3 you saw that under certain conditions choosing to abstain from a problematic sexual pattern can be useful. But I’m convinced that a premature emphasis on abstinence increases the intensity of troublesome sexual urges by encouraging the struggle that fuels them. The erotic equation has shown us why fighting a sexual impulse only makes it stronger.

Alcoholics and other substance abusers usually have only one choice when it comes to their preferred drug—stay away from it. But no matter how compulsive sexual behavior may become, for erotic healing to take place, an increasing range of self-affirming choices must be claimed for oneself. One’s power to choose is ultimately what induces sexual well-being.

WHAT ABOUT THERAPY?

All the people you’ve met in the last three chapters have worked with me in therapy. A supportive, nonjudgmental atmosphere facilitates disclosure of erotic secrets. In addition, some sort of therapeutic involvement is usually necessary to help uncover memories and beliefs that operate unconsciously. I’m not suggesting, however, that everyone with an erotic problem should enter therapy. Many people can make considerable progress on their own—if they are sufficiently motivated and know how to proceed.

Nevertheless, it’s very difficult to probe the many layers of your erotic mind by yourself. It’s a great relief to discuss thoughts and feelings honestly with at least one other person who genuinely listens without pushing any particular agenda. If you’re fortunate enough to have a friend who listens respectfully and discloses intimate information of his or her own, perhaps the two of you can help each other with series of discussions.

Although many people consider their lovers or spouses their best friends, there’s no set rule about how many of your deepest erotic yearnings you should reveal to your partner. No matter how intimate your relationship, your lover can never be truly neutral about all your turn-ons, especially ones involving other people. Many partners are also threatened by details about each other’s past experiences. That said, I’ve known many couples who openly discussed the most private erotic matters and grew much closer—and quite stimulated—as a result. Especially when the time comes to try out new forms of sexual expression with a partner, your experiments are much more likely to be beneficial if the two of you communicate honestly about your intentions and feelings ahead of time.

Sometimes problematic erotic patterns are so much a part of who you are that you are unable to see them clearly—let alone resolve them. Then it may be wise to consult a therapist. But how do you know when to seek professional help? If two or more of the following statements apply to you, at least consider therapy:

- • Even though I know something’s wrong erotically I can’t seem to define what the problem is.

- • In spite of my best intentions I’m unable to initiate a change—even though I know what I’d like to accomplish.

- • The attempts at change I do make don’t seem to lead me anywhere.

- • I’m uncovering disturbing memories or feelings that I don’t know how to handle.

- • I sense an inner conflict is sapping my energy but don’t know how to call a truce.

- • I continue to engage in certain sexual behaviors despite potentially damaging consequences.

It’s not easy to find a therapist with whom you can work effectively. Believe it or not, many therapists, including some sex therapists, are uneasy about discussing the nitty-gritty details of eroticism. Interview several therapists and ask them to explain how they work with erotic problems such as yours. Be wary of therapists who seem to hold dogmatic beliefs about what healthy eroticism should be. Trust yourself and speak up if something doesn’t feel right.

If you’re already in therapy for other concerns, you may be reluctant to initiate discussions of erotic issues even if you suspect they are related to what you’re working on. Therapists often don’t inquire about your sexuality, so you might have to bring it up yourself. If certain parts of this book feel particularly relevant, discuss them with your therapist as a way of raising the subject.