6. The language of graphic design

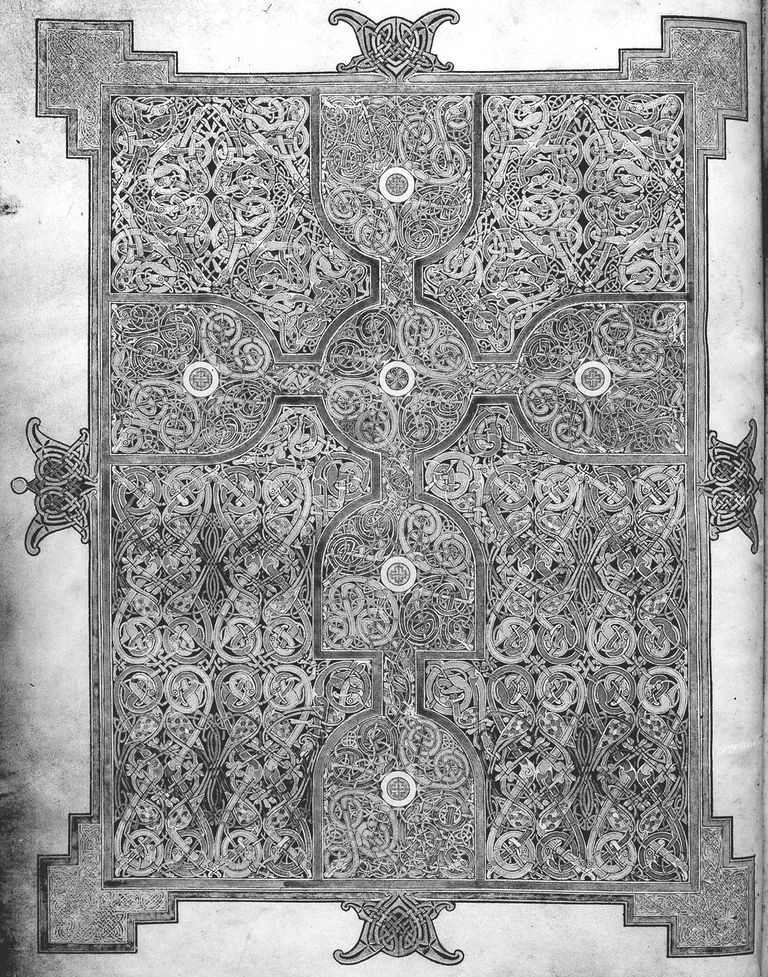

Detail of a page from the Lindisfarne Gospels, United Kingdom, c. 700 A.D.

This folio exhibits a breathtaking complexity. Geometric interlacing similar to that found in Arab art, as well as in depictions of wild pagan monsters, served as a vehicle to illustrate the Gospels. For all the apparent license taken in their creation, these images were made according to rules and mathematical schemes. Organic and geometric shapes are kept strictly separate and, within each animal compartment, every line is connected to the animal’s body.

British Library, London; Ms. Cotton Nero.D.IV, fol. 26v

Science has influenced most human activities by developing novel techniques. Prehistory was defined by the Stone, Bronze and Iron Ages, terms that referred to the relevant technologies of the time. Likewise, history—the era of written communication—is classified by the making of clay tablets, parchment, typesetting and computing.

Today, the demand for visual communication is at an all-time high, accelerating the development of ever-new techniques. Our near future is perceived in cybernetic terms as television, video games, computers and other electronic devices have all become part of an interactive network—blurring the traditional divisions of art and science.

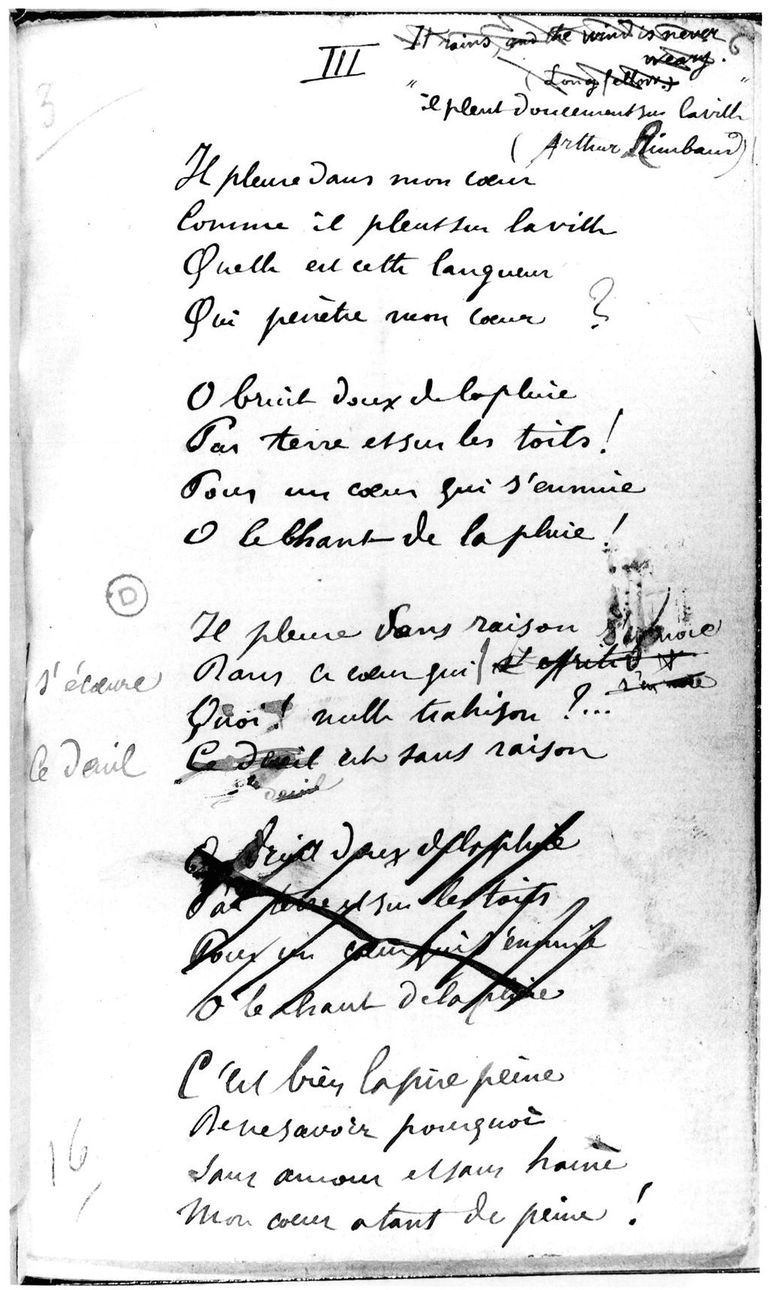

Poem by Paul Verlaine

In comparing the handwritten with the typed version, one cannot but think that with each new technological advance we benefit, learn and … lose a little.

Bibliothèque Littéraire Jacques Doucet, Paris

Il pleure dans mon cœur

Comme il pleut sur la ville.

Quelle est cette langueur

Qui pénètre mon cœur ?

Ô bruit doux de la pluie

Par terre et sur les toits !

Pour un cœur qui s’ennuie

Ô le chant de la pluie !

Il pleure sans raison

Dans ce cœur qui s’écœure.

Quoi ! nulle trahison ?

Ce deuil est sans raison.

C’est bien la pire peine

De ne savoir pourquoi,

Sans amour et sans haine,

Mon cœur a tant de peine !

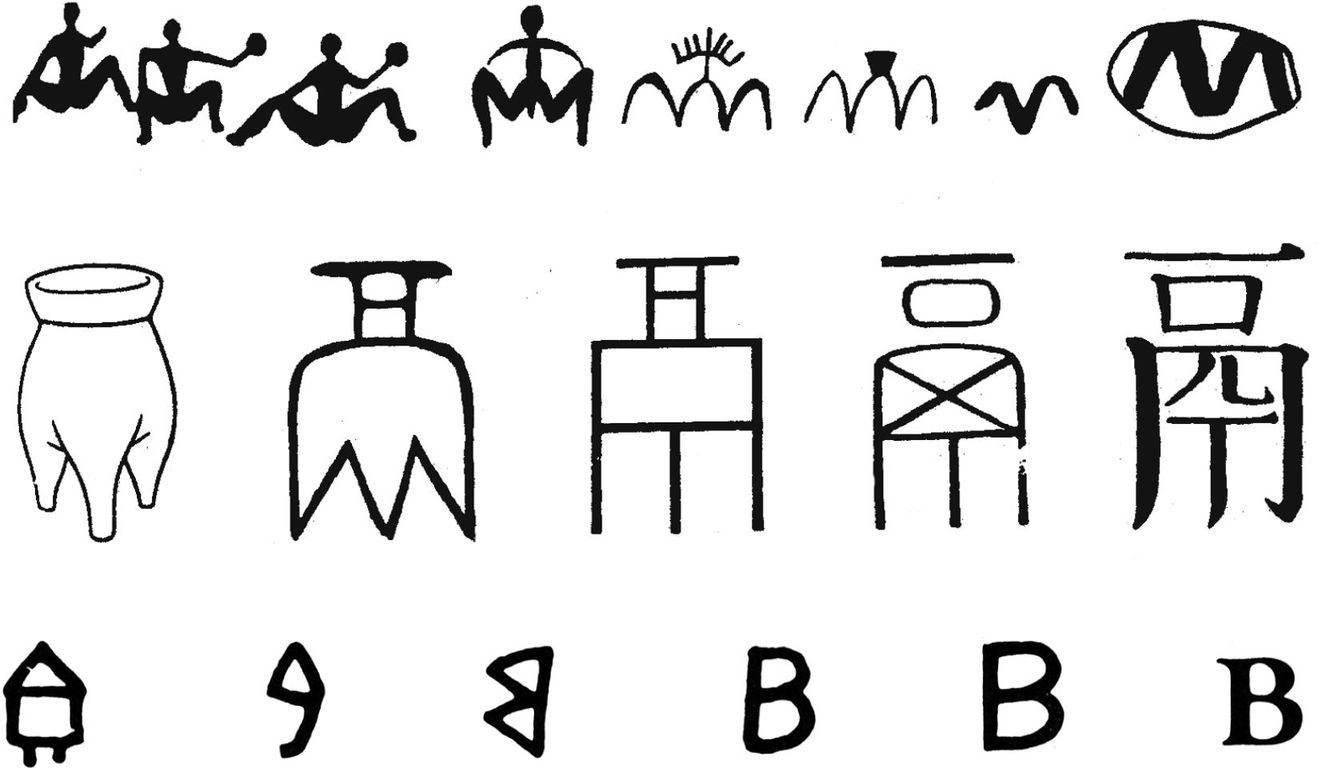

During prehistory man apparently began painting, drawing and carving in different parts of the world. While color is an emotional component, drawing and writing are more intellectual activities.

The oldest-known pictures had a ritualistic or utilitarian purpose, and hence what we view as the beginning of art should also be regarded as the dawn of visual communication.

“Primitive” art is often associated with abstraction, yet early images were highly naturalistic; only much later did formal simplification occur. By the late Stone Age pictographs—early writing with figurative or symbolic drawings—were so stylized that the step towards using written characters seemed a relatively small one.

TOP: Prehistoric drawing analyzed by Abbé Breuil

CENTER: Chinese art analyzed by Silcock

BOTTOM: Development of the Latin alphabet

Many forms of writing are derived from the gradual schematization of drawings. By combining pictograms it became possible to express ideas. In some languages, ideograms were used to express the sound corresponding to the idea. Thousands of symbols could be summarized in a few phonetic symbols, and thereafter translated into alphabetical signs. The Chinese, on the other hand, chose to keep their numerous beautiful characters.

Writing was developed in Mesopotamia over 5,000 years ago and contributed enormously to civilization, as it preserved hard-earned knowledge and passed it on to future generations. At an early stage, grids contained pictographs within spatial divisions; they were eventually turned on their side and written in a linear fashion in horizontal and vertical rows.

Pictographs were abstracted into a system of cuneiform (wedge-shaped) signs, which were inscribed into clay tablets. Speed increased when triangular-tipped styluses replaced the traditionally pointed ones, enabling the new implement to be pushed instead of dragged through the clay.

The need for efficient record-keeping alone was sufficient to keep scribes employed in officiating over large-scale temples and finding techniques to facilitate their construction. Information was already an important business.

The library of King Assurbanipal (c. 668–625 B.C.) contained over 20,000 clay tablets that were inscribed not only with commercial facts and figures, but also texts on history, medicine, astronomy and astrology.

Over a 2,000-year period, several languages were written in cuneiform characters, which were gradually simplified.

Clay tablet with medical text in cuneiform characters, Nippur, Iraq, c. 2100 B.C.

In Mesopotamia, clay was the prevalent writing material, although to draw shapes in wet clay was not an easy task. This is probably one of the reasons why a simple linear system was developed there.

University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia; Object 14221

Cylinder seal (the “Tyszkiewicz Seal”), overall view and impression of side and base, Hittite, fourteenth century B.C.

This seal, which is both decorative and practical, was used as a signature. The motifs range from figurative to totally abstract.

Cylindral intaglio gem with hematite handle, height: 23⁄4 in. (5.8 cm), diameter: 7⁄8 in. (2.2 cm)

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Henry Lillie Pierce Fund, 98.706

The Egyptians, who were in contact with the Mesopotamians, decided to develop a different writing system based on hieroglyphs (“sacred sculptures” in Greek)—which embodied the beauty of their universe. It was a highly complex system based on a combination of different types of figurative, symbolic and phonetic signs.

Becoming a scribe required years of initiation. The highly respected guardians of knowledge were trained in land-surveying and accountancy, as well as in art and science. They kept their writing system for restricted use and developed simplified forms for business and popular purposes.

Egyptians wrote on papyrus—made of moistened strips of thin slices of reed pith, superimposed at right angles and pressed—instead of on rigid tablets. Because the Egyptians wrote on papyrus scrolls, they perhaps produced the first documents that combined words and images.

Along today’s Syrian-Lebanese coast, the Phoenicians, around 1650 B.C., using the cuneiform system on papyrus, simplified it to twenty-two totally abstract phonetic signs. The alphabet is a series of visual symbols, each standing for an elementary sound. These signs soon spread throughout the ancient seafarers’ world.

Who brought the alphabet to the West is not known for sure, but legend points to Cadmus of Miletus, also credited for having invented prose. The Greeks called the imported documents byblos, which was the name of their Lebanese export center (byblos means “book”). They adopted a simple and democratic alphabet, and developed its utility and beauty, changing five of the consonants into vowels as connecting sounds to make words.

In Ancient Greece, more than in any other civilization, beauty and knowledge went hand in hand. It is tempting to think that the Greeks, too, illustrated their manuscripts, but we have no proof of this. By the time of Alexander the Great (356–323 B.C.), the demand for information required an orchestrated, large-scale effort. Alexander founded several libraries; the major one in the port of Alexandria housed up to half a million manuscripts. Anchoring ships were required to hand over documents for rapid copying. Each visitor had to lend them for that purpose and ships were searched to make sure nothing was withheld. A famous quarrel took place when Athenians lent out manuscripts of Greek tragedies and received copies back instead of the originals.

Detail of a Greek papyrus manuscript, c. fourth century B.C.

Even though Greek, Latin and Carolinian alphabets have the same origin, each culture has left its own mark. Greek characters, like those used to transpose Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, are harmonious and rhythmic. The words logos, harmonia and arythmos have related meanings.

Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

When Alexander’s empire was split up after his death, his generals unwittingly expanded civilization by broadly introducing the Greek alphabet. Languages such as Etruscan and Latin developed as a result, as did sometime later Armenian and Cyrillic—after the Byzantine priest Cyril (ninth century) who devised an alphabet for the Slavs’ language.

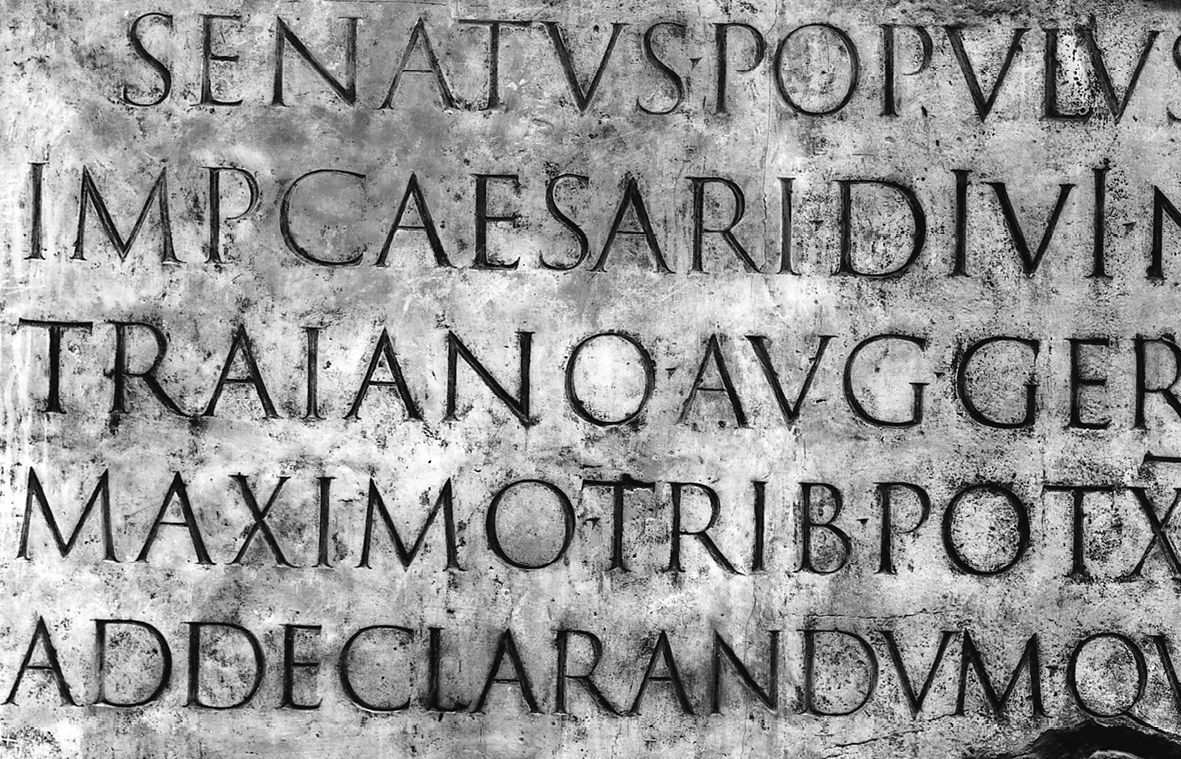

Carved inscription on Trajan’s Column, second century A.D.

Roman lettering is sculptural and majestic. The artisan first calculated the number of letters and their size, making a scheme on papyrus, before drawing on stone and engraving the inscription. The Romans anticipated the shadows of the sculpted capitals, and incorporated these into their writing style (derived from stylus, the object used by the Romans for writing).

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Most ancient repositories of culture were lost; for example, of the 330 known Greek plays, only a few dozen have survived. Yet from Hellenistic territories the legacy of antique art and science spread east and west.

In Greek, the word graphein applied similarly to writing, drawing or painting. There also was an analogy between graph and glyph (sculpted image). As in ancient pictographic principles, most alphabets exhibit a unity of idea and image.

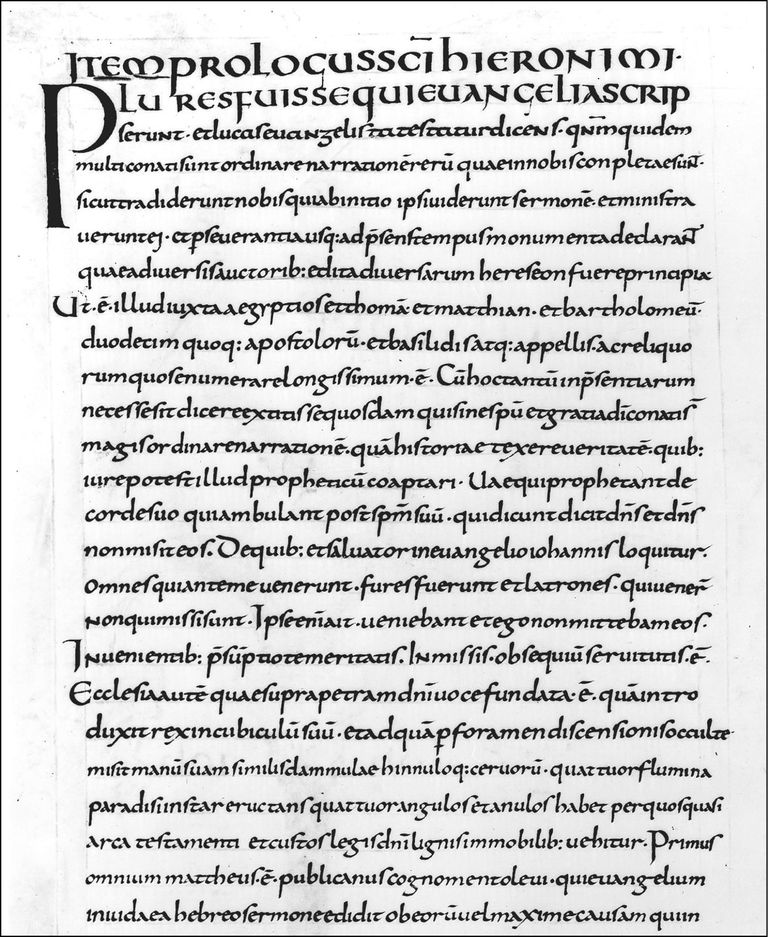

Carolingian lower-case letters in the Alcuin Bible, ninth century

The Romans developed a smaller, roundish writing style for daily use. Inspired by it, Carolingian writing looks even simpler and reflects an economical approach. According to legend, the great Charlemagne tried to learn how to write (hiding his notebooks under his pillow in order to practice at night)—but he never succeeded!

British Library, London; Add. Ms. 10546, fol. 351v

The story goes that Ptolemy V of Alexandria and Eumenes II of Pergamon (Turkey, c. second century B.C.) were engaged in a fierce rivalry in the papyrus-scroll trade. Because the Romans had embargoed Pergamon’s shipments, its citizens proceeded to make parchment (which possibly takes its name from Pergamon) to fill the gap.

Made of animal skin, of which vellum is the finest form, parchment sheets were larger, smoother and more durable than papyrus. Even though parchment was more expensive, both sides of the page could be used, which considerably reduced storage space and also did away with the time-consuming necessity of rolling and unrolling the scrolls, which suffered considerable wear and tear in the process.

Page from the Lindisfarne Gospels, United Kingdom, c. 700 A.D.

Patterns on parchment were first drawn on the back of the page. The key points of the design were pricked through the vellum to provide guidance to the painter. Instruments of measurement such as the compass and the square were commonly used.

British Library, London; Ms. Cotton Nero.D.IV, fol. 26v

As the parchment writing surface became widely used, the change, around the fourth century A.D., from scroll to codex (“book” in Latin) must have been a major stimulus to illustration. Parchment does not absorb color, which makes pictures look brighter.

Calligraphy, and then illustrated texts, became a dominant art form which the Arabs turned into a tool for science—whose ancient form was rewritten and revised. Intellectual centers developed across their territories: in Spain, the Cordoba Library contained more books than the whole of France.

Later, Christianity became the primary fount of writing in the West. Manuscripts written in silver letters on purple vellum show that the art of miniature reached a high level early in the Middle Ages. Minium, a red-brown pigment made of a lead derivative mixed with egg, provided the name “miniature.”

Benches in the Old Library, Trinity Hall, Cambridge University, England, c. 1590

Parchment led to the use of the goose quill. A quill was carefully selected, then softened by soaking for several hours. Once dry, it was sharpened and shaped to function in the desired style. Because of its flexibility, the quill facilitated the development of new writing styles. Towards the end of the Middle Ages, lead pencils, paper and notebooks also contributed to the development of written communication. To meet the needs of a growing number of students, a system of lecterns and shelves was installed; books were secured by chains.

Religious manuscripts, whose pages were lavishly decorated with gold, silver and precious pigments, were produced in monasteries. Gold was ground or hammered on to an adhesive background or was applied as leaf, which produced a dazzling “illuminated” effect. Monks often added touches of fantasy to their scholarly and decorative work. Monasteries in Ireland and England were prominent intellectual centers.

Manuscript production went into high gear during the reign of Charlemagne, who recruited Alcuin of York (735–804), a leading historian, as his personal advisor on education. Since few people could read or write, audiences had to be read to; readers and writers were distinct types of specialists.

Under Charlemagne’s authority, the Roman alphabet was further developed: written texts were structured by punctuation marks and paragraphs, which simplified the transcription and the interpretation of manuscripts.

The most celebrated illuminated manuscript, the Trés Riches Heures, was commissioned by the Duc de Berry (1340–1416). He owned the largest private library in the Western world, containing over a hundred books, the production of which he personally oversaw. The miniature paintings in these volumes were remarkable for their detail and brilliant colors.

The production process was complex and expensive. Hundreds of sheepskins had to be prepared to furnish the high-quality vellum, to which precious metals and pigments were applied by teams of scribes and illustrators. The cost of a single book, with its elaborately carved cover inlaid with ivory and precious stones, could easily amount to the purchase price of a large estate or a top-quality vineyard.

The art of copying antique documents, which was how some of the greatest works were saved, constituted the main artistic and scientific endeavour of the Middle Ages. But, with the invention of movable type just a few decades away, the thousand-year-old craft was doomed.

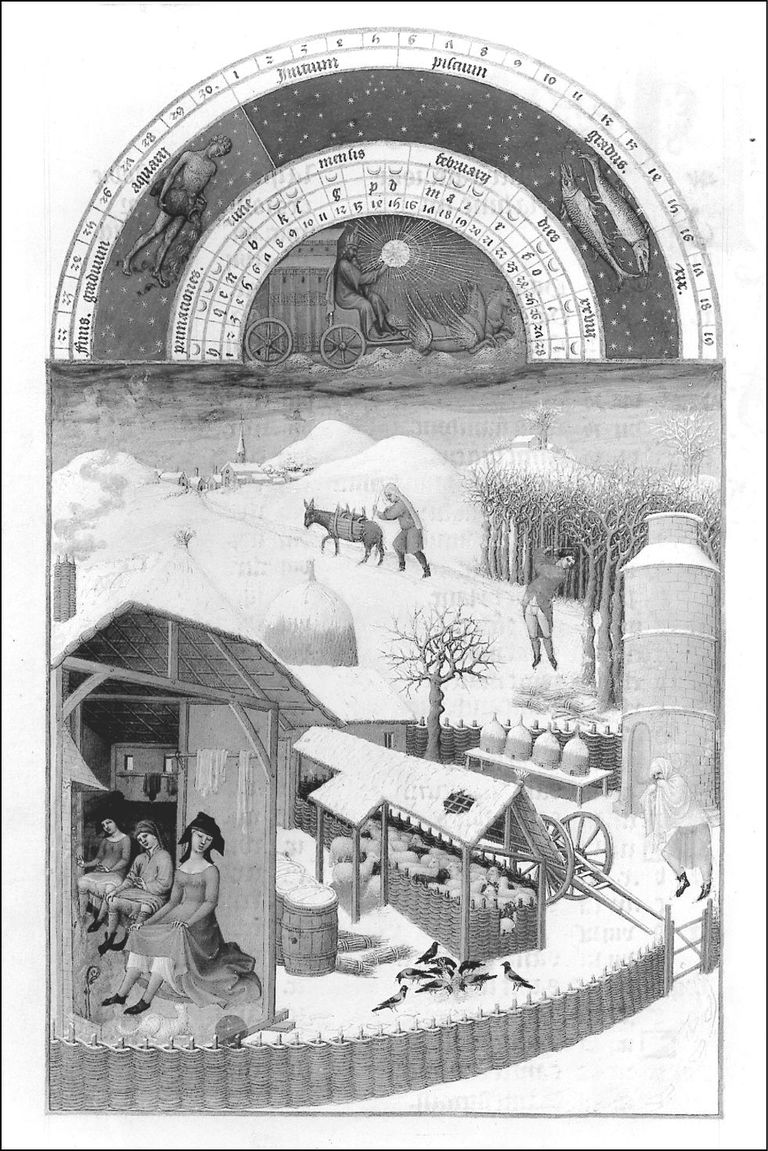

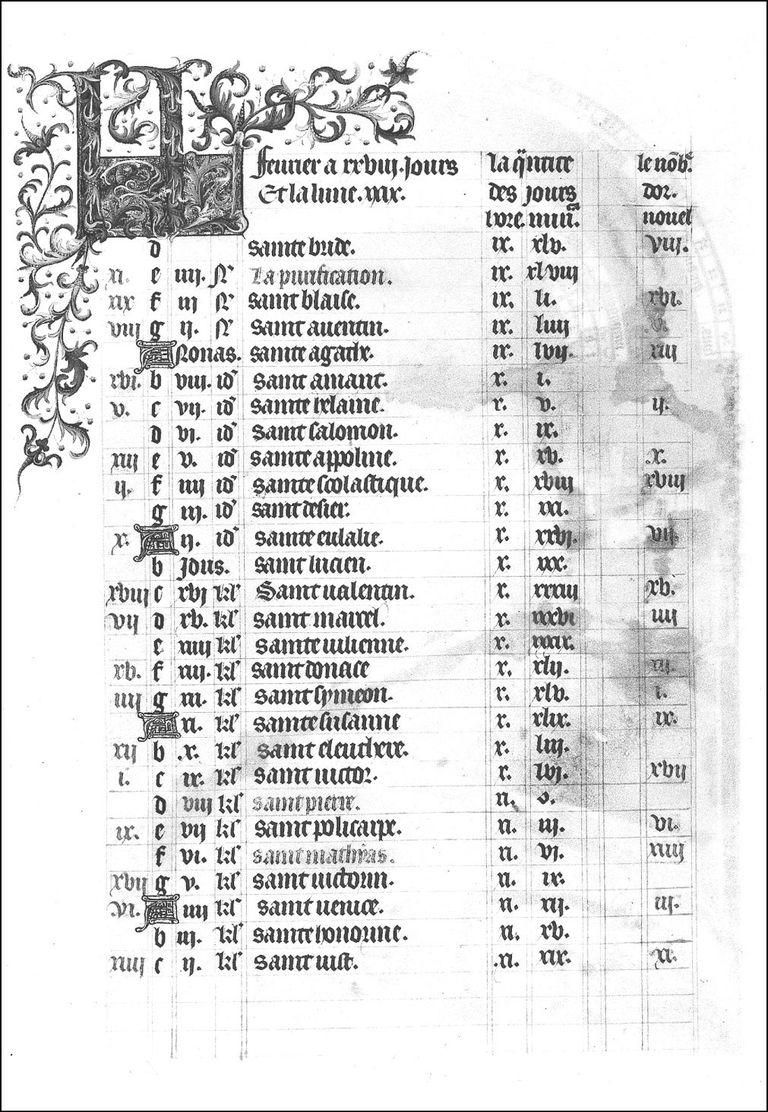

February, miniature and text in the Trés Riches Heures, Limbourg brothers, early fifteenth century

This picture is the earliest representation of a snowy landscape in the history of Western art. In the finest illuminated manuscripts, pictorial and written information reflect a high level of visual integration. Narrow Gothic characters were appreciated because many could be fitted on a single page of costly parchment.

Musée Condé, Chantilly, France

Death of a thousand-year-old art

According to legend, the ancient Chinese invented calligraphy (c. 1000 B.C.) by contemplating the clawmarks of birds and animal footprints. They wrote on wood or bamboo, cheap and readily available materials, or on silk which was costly to produce. Around 105 A.D., the eunuch Ts’ai Lun developed a process for fabricating paper and was deified as the god of paper-makers. In fact, paper had been known much earlier. As a lightweight material, it was perfectly adapted to hair or silk brush calligraphy. The finest scrolls were made by gluing sheets together and decorating them with materials such as jade.

Paper was used across Asia for various practical purposes. After winning the Battle of Samarkand (712), the Arabs took possession of Chinese paper-making secrets and jealously guarded them for another five hundred years. In the twelfth century paper was finally introduced to Europe, where Ts’ai Lun’s method continued to be used, almost unchanged, until the Industrial Revolution.

A simple relief-printing technique existed long ago in China. It was derived from an old custom of making inked rubbings from carved stones, and perhaps also from using Middle-Eastern engraved seals. Exactly how and when relief printing was invented is not known.

Traditional paper-making techniques from China

The craftsman holds a tray that contains a mixture of disintegrated wood-pulp fibers. Various plants were used in the production of paper, much earlier in China than in the West. Anyone who has handled an ancient book made of linen knows how fresh it remains. Newer books with paper bleached by chlorine decay rapidly.

Ontario Science Centre, Toronto

The oldest surviving relief-printed books (ninth century) attest to the incredible artistic quality attained by early Chinese printers. By this technique they made encyclopedic works, sometimes 100,000 pages long.

On pilgrimage routes there was a great demand for religious pictures, which were printed from carved slabs of stone or wood, and from bronze plates. The demand for playing-cards was high, too. (As in Ancient China, numerical sequences and royal figures feature in today’s cards.)

The earliest characters of movable type were developed by the alchemist Pi Sheng (c. 1000 A.D.). Chinese writing contains more than 50,000 characters, which are neither alphabetical nor syllabic, but logographic: each sign represents an entire word and there is no relationship between the written and spoken language. In addition, a single sign may carry multiple interpretations, depending on how it is pronounced. All this made typesetting very impractical.

More importantly, the Chinese placed a premium on calligraphy, in which breathing and concentration, body and physical language, are interwoven. Calligraphy was an art form considered superior even to painting, as well as a science whose mastery commanded the highest respect. Thus there was no pressing need to develop printing.

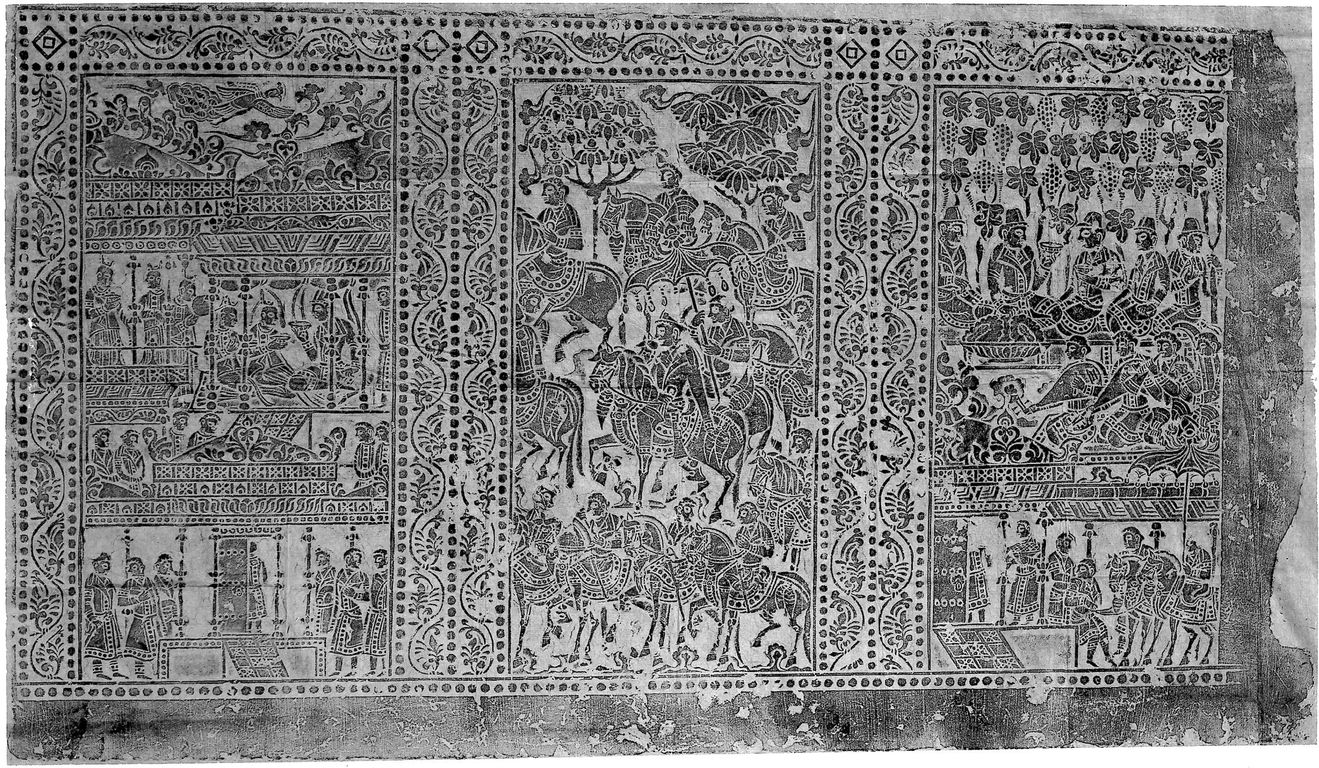

Rubbing from a mortuary couch stone, Northern Qi dynasty (550–77 A.D.)

The Chinese developed relief printing by taking high-quality inked rubbings from carved stones.

181⁄2 × 441⁄8 in. (47 × 112 cm)

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Gift of Denman Waldo Ross and G. M. Lane

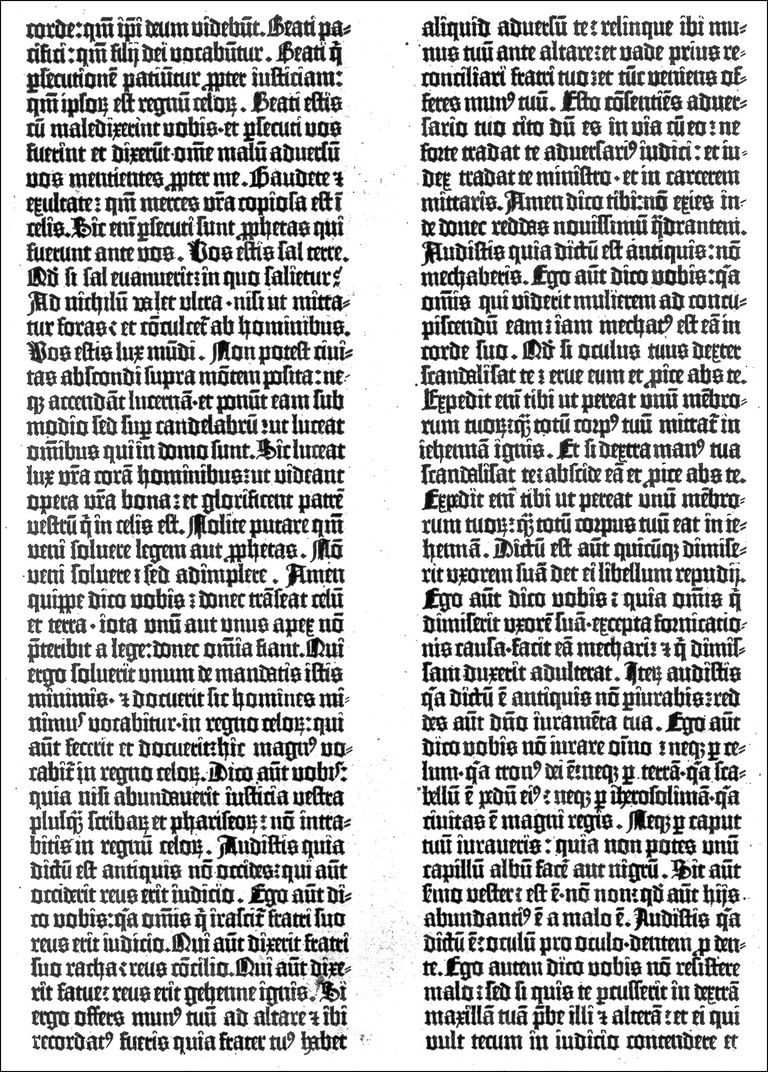

Page from the Gutenberg Bible, 1450–55

Gutenberg was the father of Western printing. For two decades, he experimented to find a suitable metal alloy that would flow easily when heated and make reproduction-quality characters. He sought to discover the right black and colored inks—probably based on Flemish painters’ experiences—and the right kind of paper. Most importantly, he produced the optimal “screw press” for making impressions in large numbers, daily. When the first typeset book appeared, the Gutenberg Bible, its visual clarity and aesthetic qualities heralded typography as a superior art form.

Paper and various concepts relating to movable type were progressively introduced in the West, where they found a knowledge-hungry audience and a growing need for application in business administration. The development of typesetting, that is, printing with independent, reusable standardized characters was, after writing, the most important step in the advancement of civilization.

It is generally accepted that Johannes Gutenberg (1394–1468) brought the different technologies together. From his father who worked at the Mainz mint, he learned all the tricks of working metal. A successful metal- and gem-cutter, he spent decades in developing the printing press.

After nearly two decades of Gutenberg’s research, Johannes Fust, who had provided him with financial backing, suddenly sued for not having received interest on the loans. Taking all of Gutenberg’s assets, Fust created the largest worldwide printing firm, including his famous Bible. It is said that the legend of Faust, in which the protagonist traded his soul for power, had its source in Gutenberg’s misfortune.

Gutenberg’s printing technique was no mere collection of technical recipes. The physical presentation and visual impact of texts were prime concerns from the very beginning, which also explains why illuminated manuscripts ceased to be produced after a few decades.

Over the same period, printing was established in the West. By 1480, presses existed in more than twenty northern towns and twice as many appeared in the south. In Venice, Aldus Manutius (1449–1515) translated and printed nearly all available antique works, the content of which was saved for posterity.

While “how to do it” manuals appeared in every possible field, Venetians complained that there were already too many books—thus the portable format was adopted.

The notion of authorship grew in importance, as did indexing and filing, needed to help organize rapidly developing collections. Sequential ordering of pictures, words and ideas, provided in a reproducible and verifiable form, were the conceptual pillars of Western progress.

Drawing changed radically when paper was introduced. Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), in the south, and Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), in the north, established the new way of drawing as a common system, integral to the graphic arts, architecture and science alike.

Leonardo used perspective theory and practice, trusting only direct observation and his own experience. The object of his life was saper videre, or to know how to see. “He who loses his sight loses his view of the universe. The eye has measured the distance and the size of the stars, [it] has created architecture and perspective, and lastly, the divine art of painting.”

He distinguished three aspects of perspective: linearity, color and blurring. The first deals with the apparent diminution of objects as they recede from the viewer. The second relates to changes in color as a result of recession from the eye, and the third accounts for the blurring effect, as receding objects appear less distinct.

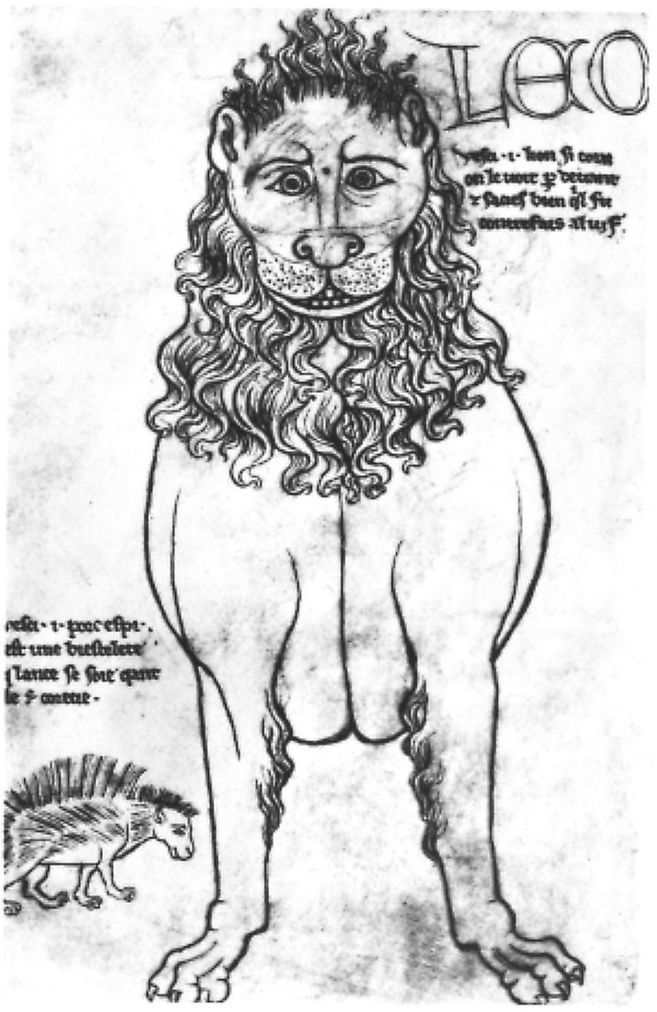

Frontal view of a lion, Villard de Honnecourt, c. 1235

Drawing in the Middle Ages was related to the flat and static architecture of stained-glass windows. Villard de Honnecourt, a widely traveled medieval builder who illustrated his projects, said: “The art of geometry commands and teaches.” In this picture of a lion, he laid down noticeable circles, one for the face and a larger one for the body.

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris; Cod. Fr. 19093

Leonardo gave a detailed description of a pyramidal theory of perspective: “Painting is based upon perspective which is nothing else than a thorough knowledge of the function of the eye. And this function simply consists in receiving in a pyramid the forms and colors of all objects placed before it. Therefore, if you extend the lines from the edges of each body as they converge you will bring them to a single point, and necessarily the formed lines must form a pyramid.”

He invented a new genre, modern illustration, which would be a determining factor in documenting and structuring the fast-growing body of information; while he analyzed motion he developed a cinematic drawing style. Even though he experimented widely, and seemingly endlessly, Leonardo never wrote a formal treatise. Instead, he left hundreds of notes and sketches—in mirror-writing since he was left-handed—many of which were found three hundred years later. They thus had a limited impact on the immediate course of science.

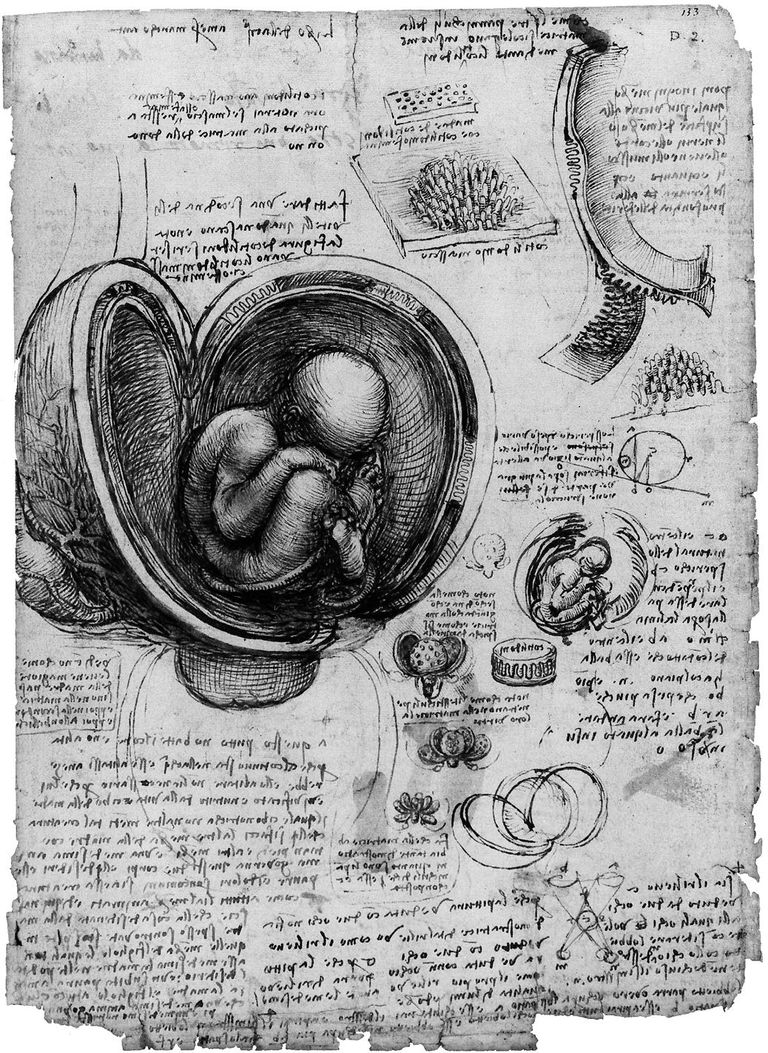

Leonardo immensely enriched the fields of ballistics and engineering, and conducted pioneering work in anatomy that covered embryology and physiology, as well as the study of expression and movement. Few of his inventions found practical application and only a small number of paintings remains: roughly fifteen can be attributed with certainty, and some of them are in a lamentable condition.

Drawing of an infant in the womb, Leonardo da Vinci, sixteenth century

The victims of the plague in the Middle Ages left behind tons of garments, which were used for manufacturing paper. Rapidly executed design such as this was directly linked to the availability of paper. Drawing evolved spectacularly during the Renaissance. Anatomical sketches were made in conjunction with the dissection of corpses. Figures were first conceived as nude drawings, then bodies were sculpted by light and clothed by color.

Royal Library, Windsor Castle; RL 19102r

His visionary scientific notes fascinate scholars, but his lasting achievement was his art. As a painter, sculptor, architect, engineer, physicist, biologist and philosopher, Leonardo was invaluable to Western culture.

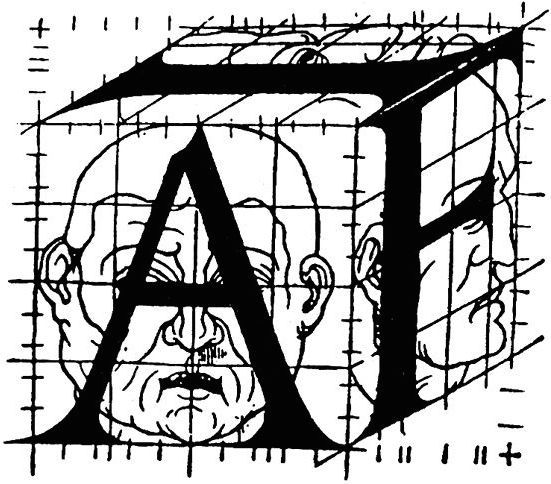

Champfleury alphabet, Geoffroy Tory, sixteenth century

Typography became an art, as indicated by the above characters. Using positions of the human body, Tory designed all the alphabet characters by means of a central zero, representing the sun, whose twenty-three rays correspond to the nine Muses, the seven Liberal Arts, the four Cardinal Points and the three Graces.

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

The first to make an organized attempt at transposing the Renaissance visual ideal to the North was the German painter and engraver Dürer, who concentrated on realistic representation. He was convinced that this could only be done by injecting scientific theory into art.

Dürer was highly regarded by Kepler and Galileo, having published the first German geometry manual. He said: “A painter [reading this book] will not only get a good start, but will reach better understanding by daily practice.” Dürer considered that his theories would be helpful to draughtsmen and painters, but also to stone-, wood-, and metal-carvers, and generally to all who used the art of measuring.

Graphic art created in this context had a three-dimensional, sculptural quality. Nuremberg, Dürer’s home, was central Europe’s most prosperous city. It was a printing capital and major producer of navigational maps and instruments. A goldsmith’s son, Dürer had extensive experience with devices, which were useful for drawing.

He was famous as an oil painter and pioneered new styles of portraits and nudes. Dürer was one of the earliest Renaissance watercolorists, yet the handling of light in his landscapes and nature studies looks astonishingly modern.

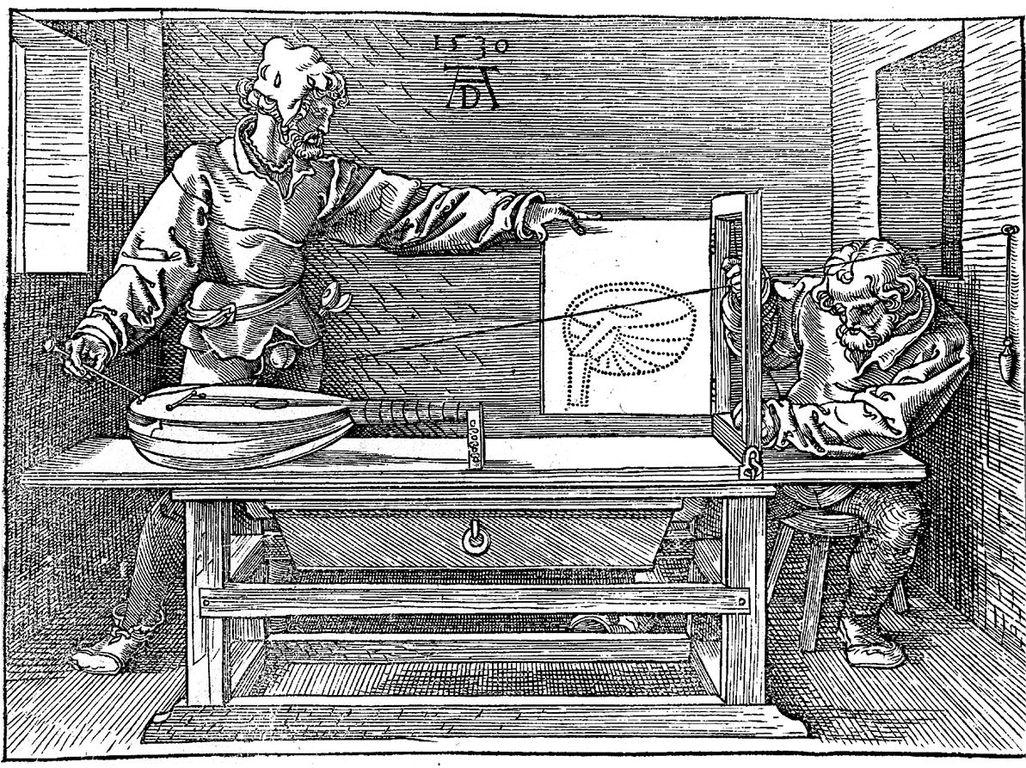

Man drawing a lute with the help of a mechanical device, Albrecht Dürer, sixteenth century

Dürer suggested that defective drawing skills could be corrected by training according to defined methods. He proposed various mechanical aids such as the “through-the-looking-grid,” in which the eye of the artist is guided by a frame divided into squares and placed between the artist and the model.

Woodcut

New York Public Library; Spencer Collection

Dürer is mainly remembered for his woodcuts and engravings, by which he transformed a craft into an authentic art form. Woodblocks were considered capable of transferring only simple images and were thus used mainly in the production of cheap prints. The multi-talented Dürer, however, succeeded in producing masterpieces from woodblocks.

Illustrators and printers collaborated with religious zeal. As a publisher, Dürer was a successful mass communicator; for him no gap existed between fine art and applied, or commercial art. German printing centers, because of the wide dissemination of their prints, had a direct impact on the Reformation. From cities such as Nuremberg and Wittenberg (Luther’s headquarters) printing spread throughout Europe.

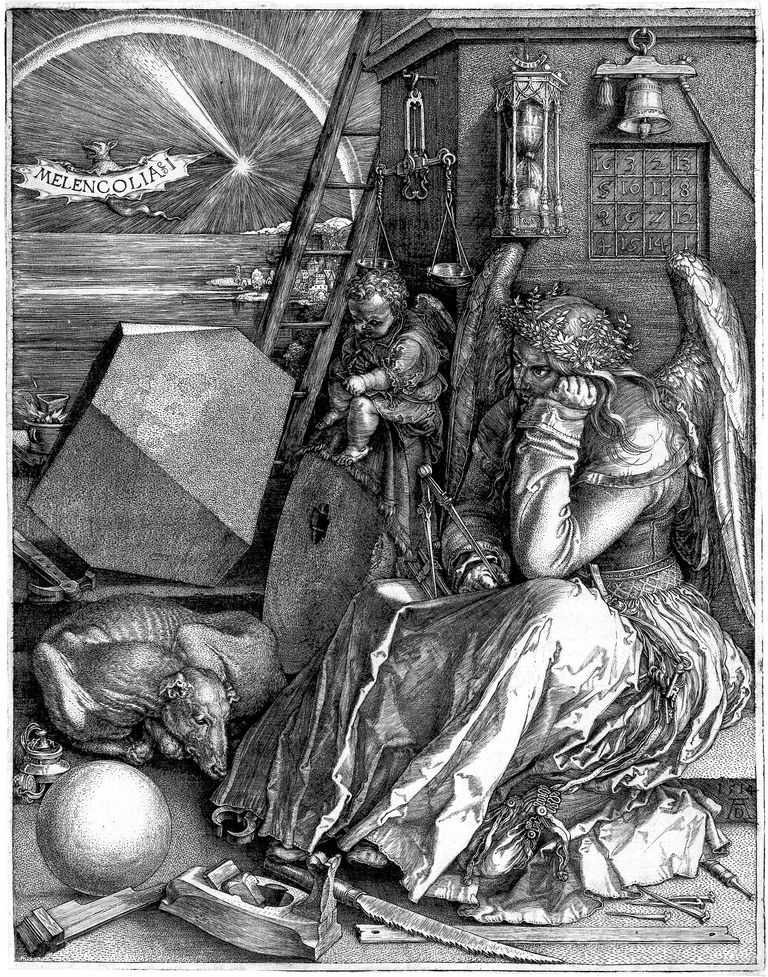

Melencolia I, Albrecht Dürer, 1514

In this symbolic image, the star pentagram represents the Brotherhood of Pythagoras: its diagonals intersect each other according to the Golden Section. Other symbols can be identified in the sphere, scale and compass.

Engraving, 14 × 18 in. (36 × 46 cm)

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Gift of Miss Ellen T. Bullard, 59.805

Venice, where the trade routes crossed, led the way in book design. Numerous typographic innovations—roman and italic characters, printed pagination, lavishly ornamented title pages and sophisticated layout—made this city a capital of elegant book printing.

The latest developments spread from Italy—to France, especially—and fostered a golden age. Punchcutters were in such demand that they gained independence from the printing companies, marking the division of publishers and printers. New typefaces, selected for their visual clarity, accompanied the introduction of the accent, the cedilla and the apostrophe, which significantly modified the structure of language.

With the persecution of the Huguenots, many of the French elite fled to England, Switzerland and the Netherlands, and took their professional skills with them. Printing empires, such as that of the Elseviers in the Netherlands, developed their activities around that time. The French printer, Christophe Plantin (c. 1520–1589), ended up in Antwerp, where he created the largest publishing house of the time. His books were noted for the excellence of their typography, and for being illustrated with copperplate engravings rather than woodcuts.

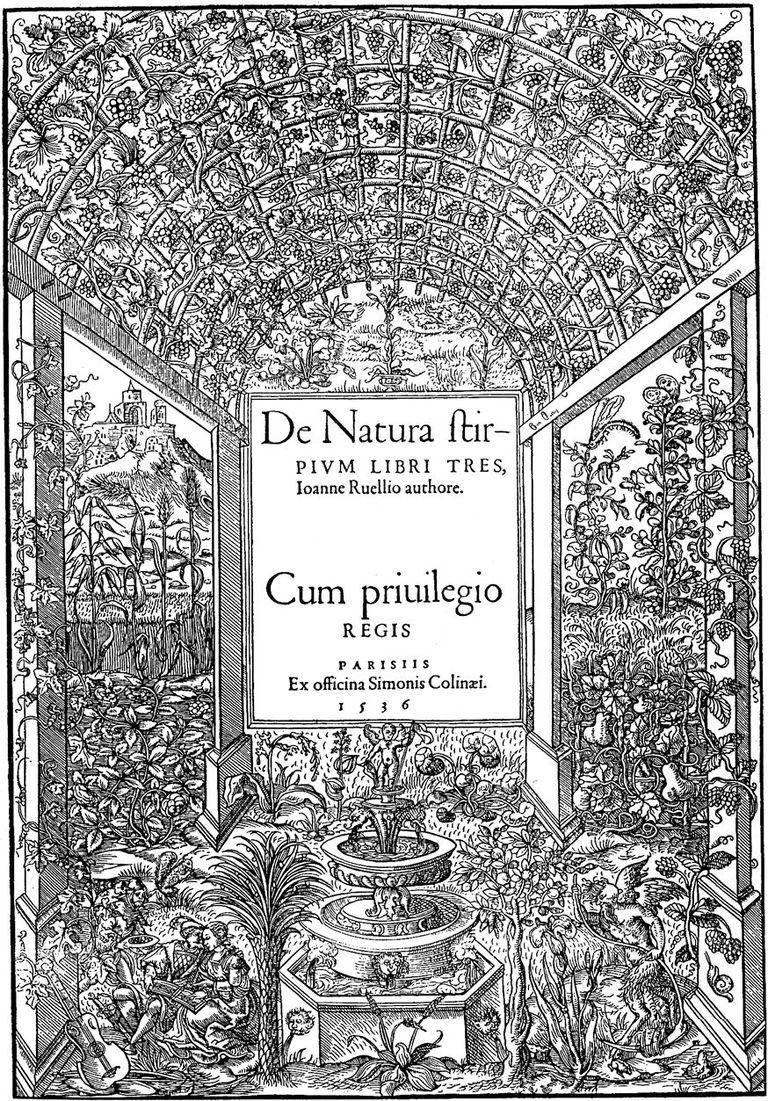

Title page for De Natura Stirpium Libri Tres, printed by Simon de Colines, 1536

As book covers tended to be individually commissioned, owners awaiting the final embossed leather product could enjoy the temporary, elaborately decorated cover, which evolved into the title page. Printing was viewed as “culturally strategic.” Louis XIV would call it the “artillery of the intellect.” He appointed a committee of specialists headed by a mathematician to develop new writing characters.

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

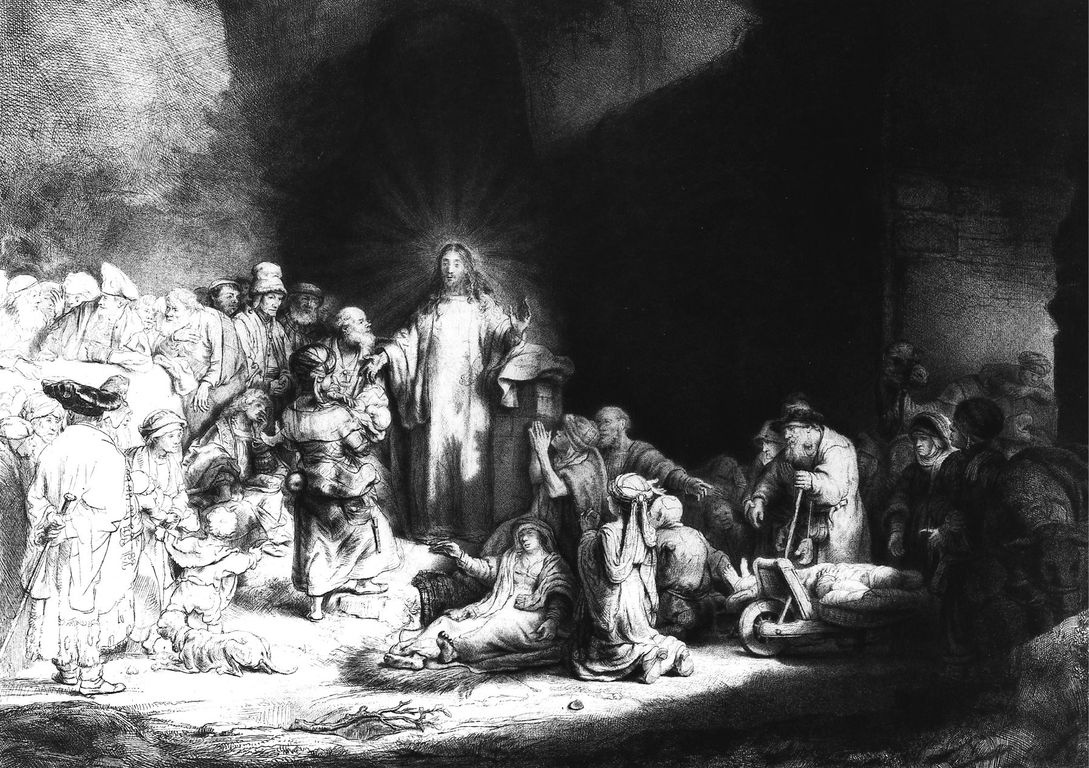

Metal plates can be worked in much finer detail than woodblocks, thereby allowing artists a greater expressive range. More importantly, metal plates can be worked in much finer detail than woodblocks, thereby allowing artists a greater expressive range. As soon as metal plates became available, engravers began to depict delicate things, such as fur and feathers, and to suggest their specific textures.

Christ with the Sick around Him, Receiving Little Children, known as the Hundred Guilder Print, Rembrandt, c. 1649

Etching, 111⁄8 × 151⁄2 in. (28.2 × 39.5 cm)

Cincinnati Art Museum; Bequest of Herbert Greer French, 1943.287

Printmakers were often adventurous artists, since printing requires visual organization and a special capability for orchestrating various steps. It belongs to a vast research continuum: the development of yet another new technique, etching, would soon impress visual artists even more.

Etching may derive from a process developed in the fourteenth century for decorating weapons and repairing rusting shields. It involves drawing with a needle on a copper plate covered with a waxy film. When the drawing is finished the plate is bathed in acid, which bites into those places where the protective wax has been removed.

This chemical reaction is thus a substitute for the exacting physical labor of scoring wood or engraving copper, whose material resistance made fine results difficult to achieve. Etching provided an expanded palette of tonal gradations and was adopted by the most creative artists.

Classification and conceptualization

Engraving, the standard method for illustration, generated a “visual revolution” comparable with that created by television. Illustrated books proliferated in all domains—scientific, artistic, religious, musical and literary.

This overabundance of knowledge that was suddenly available to the public challenged philosophers such as the Frenchman René Descartes (1596–1650) and the Englishman John Locke (1632–1704) to organize and interpret it. Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677), the Dutch philosopher (who polished optic lenses to make a living), became another participant in the construction of Western values with his book Ethics Based on Geometric Order.

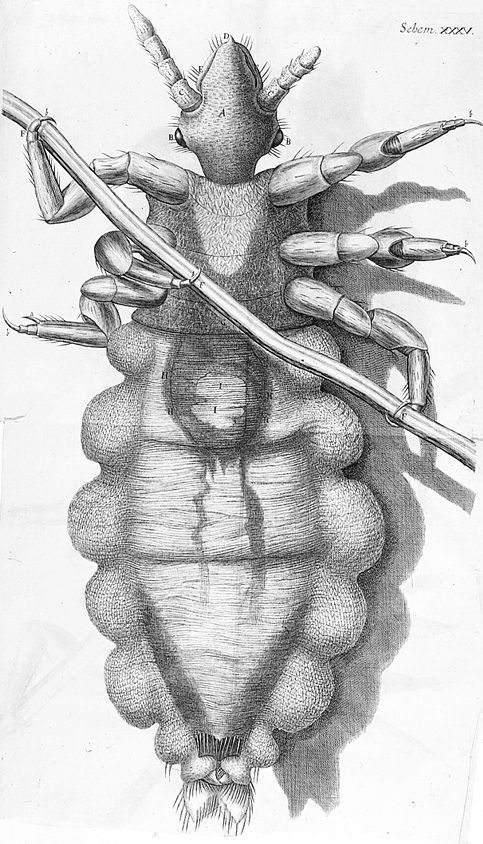

Flea clinging to a hair, Robert Hooke, 1665

Hooke (1653–1703), London’s Leonardo, was a microscopist and microscope designer. His Micrographia is a textbook on a variety of subjects including light and color, combustion and respiration. Hooke coined the word “cell,” noticing that the inner structure of cork looked like the cells in monasteries. The fundamental aspect of this observation became clear in the next century when it was discovered that cells are the basic unit of all living forms.

Science Museum, London

The Almighty was the source of all creation, but his omnipotence would soon be challenged by rational philosophers, who saw man and his environment in scientific terms, within the confines of mathematical laws. The “Enlightenment,” as seen by Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), a philosopher and physicist, was a broad reconciliation of English empiricism with French rationalism. Progress now seemed to be the essence of all things, including the chain of life.

Chinese triumphal arch in Outline for a History of Architecture, Johann Bernhardt Fischer von Ehrlach, 1721

The first modern book on architecture contributed to the dissemination of styles across borders and thus, to the development of this art form.

Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna

While new branches of knowledge were appearing, the need to impose order on knowledge was the mission of the French Count Georges de Buffon (1707–1788) and the Swede Carolus Linneus (1707–1778) who independently classified thousands of types of animals and plants, which were brought to them from all over the world. They thus developed the disciplines of zoology and botany.

Buffon, who trained in mathematics and physics, ambitiously attempted to describe all living creatures in his 36-volume illustrated encyclopedia, Histoire Naturelle. He speculated that the earth was about 75,000 years older than the Bible suggested, and he even proposed—a century ahead of Darwin—a rudimentary theory of evolution that scandalized readers.

Linneus, on the other hand, classified plants, by means of a simple system based on external features and one that is still used in the twentieth century: a binomial identifying the genus (the group to which the plant belongs) and the species (a qualifying adjective)—like a surname and a name on which everyone could agree.

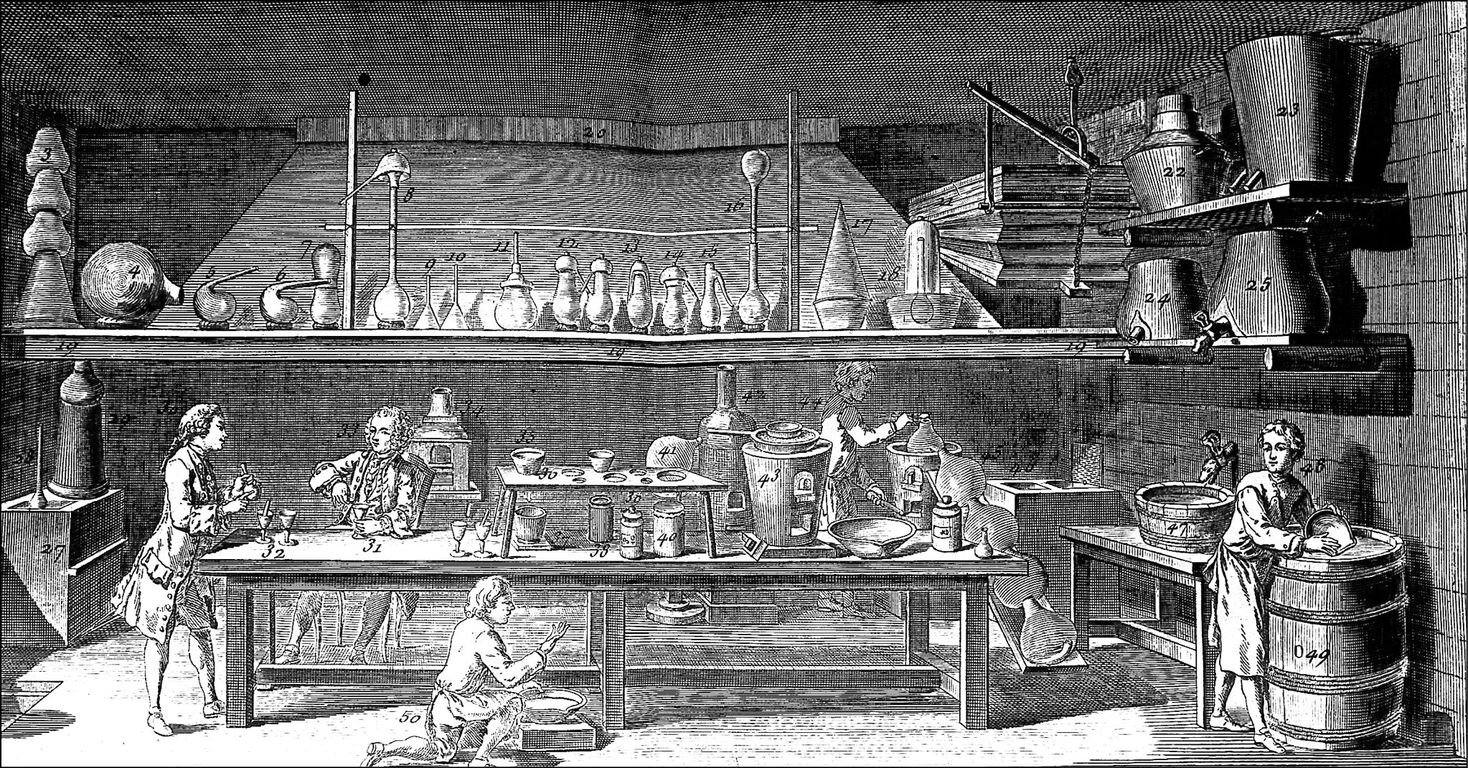

The Chemist’s Workroom in Diderot’s Encyclopédie, 1752

The first encyclopedia appeared in Great Britain. The French Encyclopédie consists of seventeen volumes of text and eleven volumes of illustrations. Jean d’Alembert and Denis Diderot were the brains behind this gigantic enterprise—Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote the chapter on music. This work marked a turning point in comparison and critique.

Linneus thus eliminated the traditional formula of cumbersome description which had hampered the establishment of systematic studies. He provided a framework for biology, in much the same way that Newton had provided one for physics in the previous century.

Since neither Descartes’ nor Newton’s systems provided all the answers, the next step was to try to arrange knowledge alphabetically. This is what Denis Diderot (1713–1784), a French mathematician and philosopher, worked on for nearly thirty years with his colleagues, compiling the Dictionnaire Raisonné des Sciences, des Arts et des Métiers, commonly called the Encyclopédie.

Diderot stated that the goal of the work was “to bring together all the knowledge scattered over the surface of the earth, and thus to build up a general system of thought, so that the work of past ages would not be useless, and our descendants becoming more instructed should become more virtuous and happier.” This exhilarating exercise of democratizing knowledge eventually led to the belief that, if widely disseminated, it could provide a solution to all the problems of mankind.

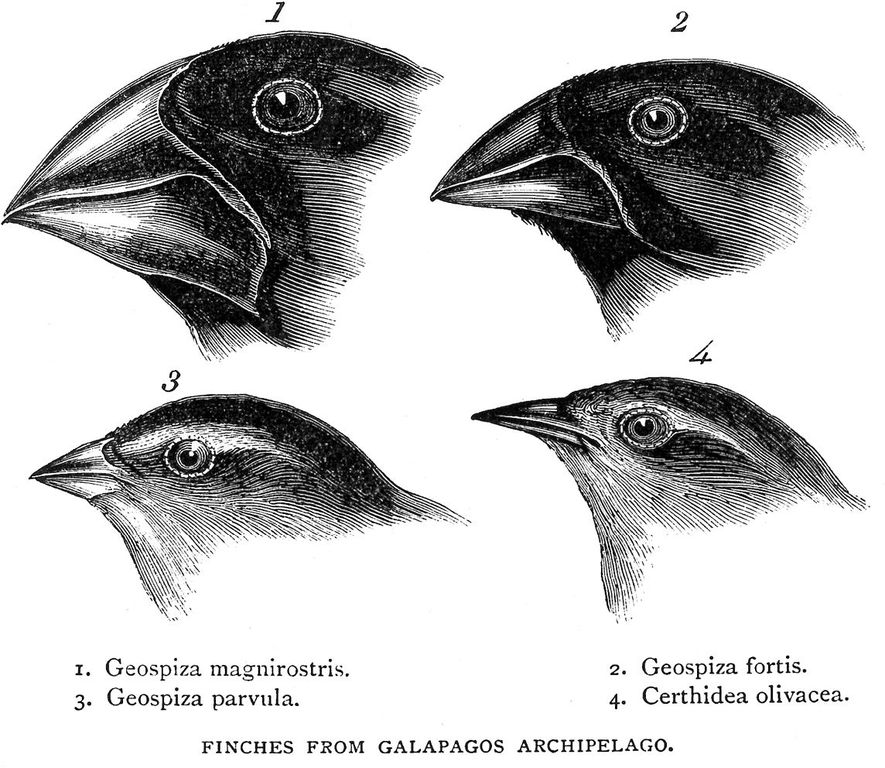

Galapagos Islands finches, Charles Darwin’s journal

Darwin carefully analyzed drawings, such as these, after his voyage. It is reported that John Gould, an artist and ornithologist, focused his friend Darwin’s attention on the link between birds’ physical features and their ability to adapt to particular environments.

Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library, University of California, Los Angeles; History and Special Collections Division

In the lavishly illustrated works of Buffon, Linneus and Diderot, vast amounts of information were presented simply, coherently and artistically. The eighteenth-century illustrators paved the way for Darwin and his theory of the evolution of species, which implied natural selection instead of a pre-determined scheme. Darwin was very lucid about the revolutionary aspects of his work, and was confident that with additional proof the next generation would understand it.

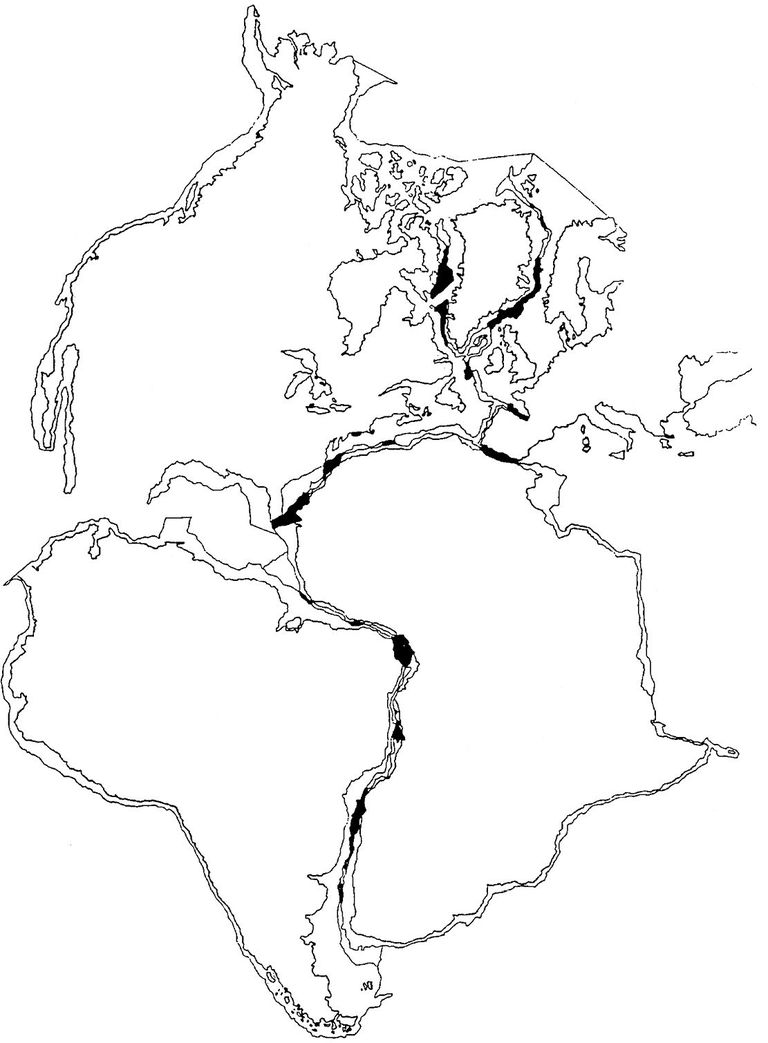

Origins of Continents and Oceans, Alfred Wegener, 1915

While studying maps, Wegener noticed that the east coast of South America and the west coast of Africa could be fitted together like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. The contours of the land masses gave him the idea that the two continents might have been joined at some time in the distant past, and that all continents had drifted away from a single one called Pangaea. This idea was later validated by an international team of geophysicists, oceanographers, paleontologists and biologists.

Throughout history, illustrators—by accurately recording their observations, making models and sketches, designing easy-to-follow diagrams and contributing methodologies—were instrumental in the development of classification and comparative analysis, thus undermining age-old concepts of right and wrong.

With the cult of knowledge, researchers in all fields could hope to shape culture instead of merely submit to what was dictated. Philosophers paved the way for the human sciences, whose laws were a counterpart to the mechanical principles describing natural phenomena. But the crowning triumph of all this activity was one of technical progress in visual communication.

The Industrial Revolution ushered in the age of mass communication. William Hogarth (1697–1764), a prolific caricaturist and clock engraver, demanded precision: he encouraged the British Parliament to protect artists against the unauthorized use of their images in printed reproduction. Thus the copyright law was born.

As time went by, printing presses, which had scarcely changed since Gutenberg’s time, were modernized and became high-speed machines, built from sturdy cast iron and powered by steam. This allowed for several thousands prints to be produced per day. Then even more sophisticated machines appeared: cylinder plates, inked rollers, new paper-producing machines and linotypes (from “line o’ type”). The latter composing machines dramatically reduced the price of newspapers, and were not improved upon until the mid-twentieth century, when photocomposition was developed. As literacy increased, a tidal wave of eclectic typographic designs flooded the pages of newspapers and books.

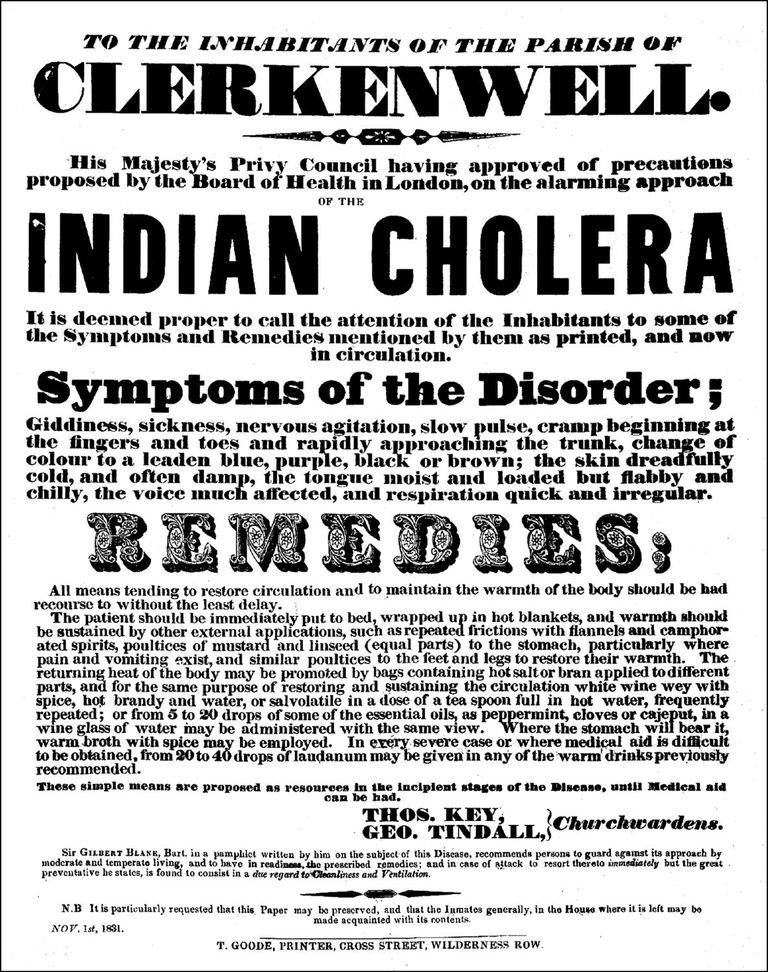

Cholera-prevention poster, London, 1831

Typographic design became full of possibilities, as shown on this poster, which was circulated in London to inform people of the impending epidemic, its symptoms and remedies.

Wellcome Institute Library, London

The story goes that, in Bavaria, the playwright Aloys Senefelder (1771–1834) was about to leave the house one day: his mother dictated a shopping list, which he happened to write on stone with a grease pencil. He had been searching for a cheap way to copy his work, and observed that the marks on the stone retained the inks because of the stone’s affinity with their fatty component. He was thus inspired to developed this method for printing.

Senefelder made a series of colored lithographs (lithos means “stone” in Greek), and predicted that some day his method would be used to reproduce paintings. The French Baron Lejeune, who was stationed nearby, brought the method back to France and suggested using it in promoting Napoleon’s campaigns.

Lithographic self-portraits, René Laennec, nineteenth century

The surface and texture of a lithographic print can closely approximate that of paint itself: the graininess comes through almost as if it were skin. These self-portraits were made by René Laennec, the French physician who invented the stethoscope; he eventually died from tuberculosis.

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

The importance of lithography was immediately evident to Francisco de Goya (1746–1828), Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), and Théodore Géricault (1791–1824). As the artist draws on a smooth porous surface, velvety textures and color variation produce a painterly effect.

Artists adopted lithography as an ideal way to experiment with flattening the picture plane, destroying the illusion of spacial recession. The technique, although cumbersome—each color requires its own stone-impression—is cost-effective since the number of prints that can be produced is unlimited. Stone endures even after copper wears out.

Thus, for economic reasons, lithography also appealed to political cartoonists, who soon employed it to good effect in newspapers and magazines.

Lithography was widely used, from illustrations in popular books to trademarks and political campaigns. Senefelder had correctly guessed that his invention would play a crucial role in the communication arsenal, and has done so to this day.

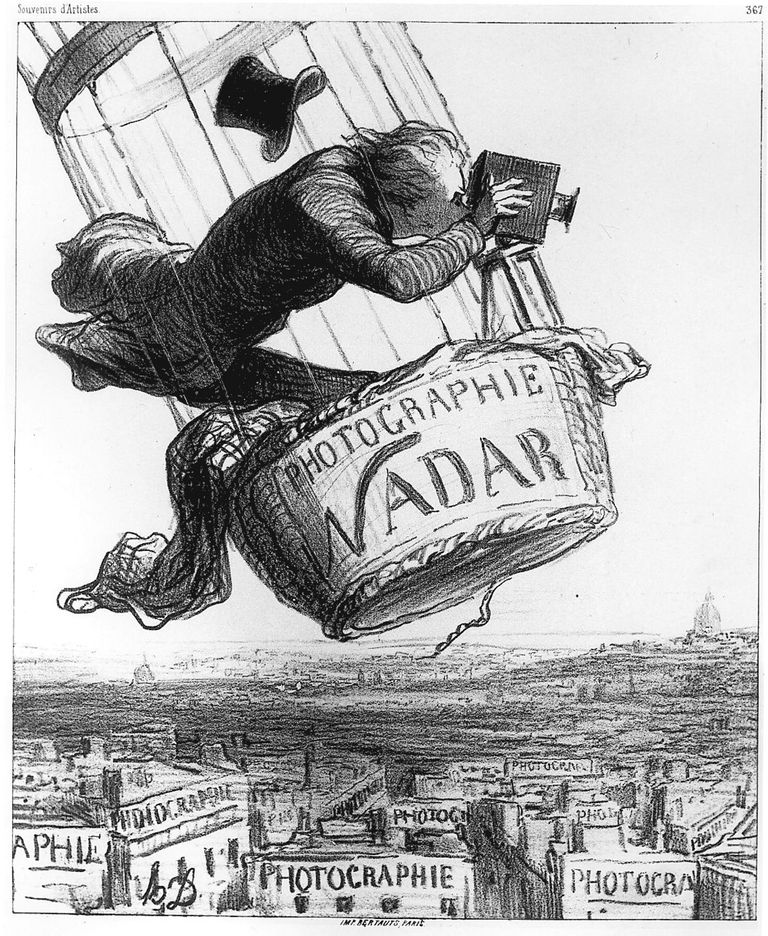

“Nadar Elevating Photography to the Height of Art,” nineteenth century

Nadar, who gave up the study of medicine for photography, became the first aerial photographer, and pioneered photography using artificial light. As cartoonist and lithographer, Nadar had an ambition to portray all the famous figures of his time. Only the first page of his Panthéon Nadar was published; it was a commercial failure. Still, it leaves us with memorable caricatures of over two hundred celebrities.

George Eastman House, Rochester, New York

Visually effective technology is a highly competitive arena in which a new goal was soon set: access for all to reproduce images by means of photography. The function of a dark chamber (or box), with an aperture, had been known since the time of Aristotle. When light passes through the aperture, it casts an inverted picture on the opposite wall. Like many discoveries, it took centuries to turn it into a practical invention.

The small portable chamber, or camera obscura, had been commonly used by artists since the Renaissance, and its opening later incorporated a lens. But no method, other than printing, had been found for “fixing” the image.

The missing link, the fact that silver nitrate darkens on exposure to light, had been described as early as 1614. Thomas Wedgwood (1771–1805), son of Josiah, the famous ceramist, was experimenting with his father’s camera obscura, and put leather sheets treated with silver nitrate inside the box. By doing so, he developed the technique of chemically fixing images. When the light struck the sheets, it imprinted them with the image seen through the aperture.

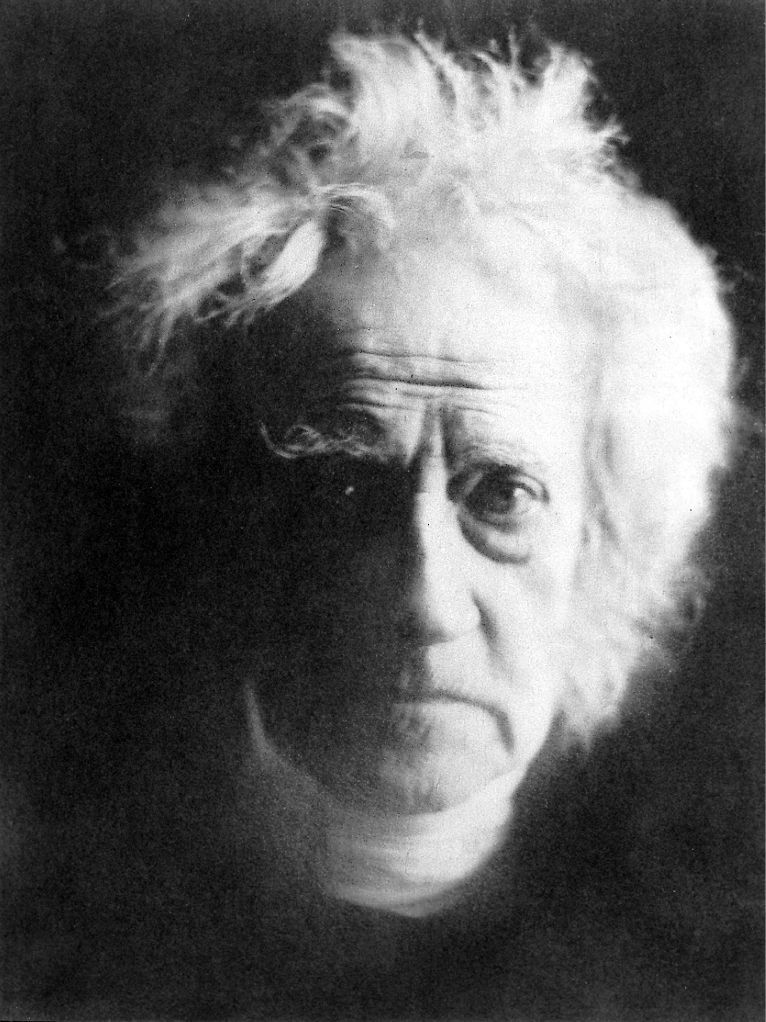

John Herschel, albumin print by Julia Margaret Cameron, 1867

Herschel played a crucial role in the development of spectroscopy and coined the word “photograph” as an analogy to the telegraph, already in use. Cameron, befriended by both artists and scientists, received photographic equipment as a forty-nintth birthday present and began to produce penetrating portraits.

George Eastman House, Rochester, New York

Various media were subject to intense experimentation. Joseph Nicéphore Niepce (1765–1833), a research chemist and lithographic printer, invented heliogravure, using sunlight (helios means “sun” in Greek). This process for reproducing images required a full day’s exposure.

Louis Jacques Daguerre (1789–1851), a French actor and skilled painter who contributed to the invention of the diorama—huge circular paintings illuminated in dark rooms that attracted the whole of Paris—teamed up with Niepce to develop the daguerrotype. The latter, a silver image printed on a copper plate, became the basis of modern photography. Even though daguerrotypes were fragile, and yielded only a single print, within the year after the invention’s public debut, half a million daguerrotypes were produced.

Meanwhile, in England, William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877), a distinguished archaeologist and mathematician who enjoyed sketching landscapes but was frustrated by his inability to capture the changing nature of light, saw photography as a solution. He devised practical photographic processes, plates and paper: his negative, from which an infinite number of prints could be made, reworked and enlarged, was revolutionary.

Exposure time was gradually reduced and fixing—which initially involved wet plates that required a considerable time to dry—was also improved upon. Switching from wet plates to dry plates liberated photographers, just as oil paint in tubes had released artists from their studios.

Most artists avoided photography, at least officially, identifying it as a threat to their mission: to represent the world around them. It did have its art-world champions, however. In particular, the English critic John Ruskin (1819–1900) saw the creative potential: “Daguerrotype helps the artist accomplish the reconciliation of true aerial perspective and chiaroscuro with the splendor and dignity of elaborate detail.”

In France, scientists helped to raise the money to support research in photography, and promoted it at the Académie des Sciences as well as at the Académie des Beaux Arts. Artists rarely got involved. Yet, Ingres (1780–1867) the French master of representation, admitted: “Which one amongst us is capable of such truthfulness, of such firmness when it comes to interpreting delicate lines and shapes. Photography is beautiful, but we should not tell anyone.”

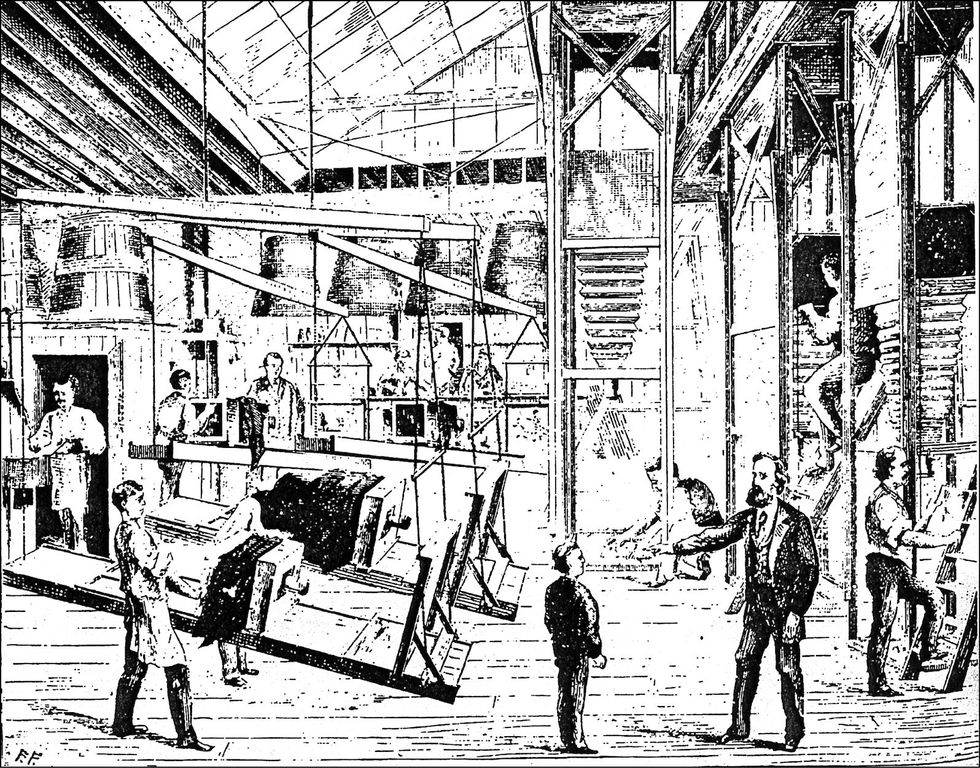

Moss photographic department, 1877

According to reporters who commented on the rise of photoengraving such reproductions had been published together with hand engravings for ten years. Readers had not noticed the difference.

In the United States, the visionary Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) established photography as an art in its own right. The European painting avant-garde, which included Duchamp, Matisse and Picasso, made a spectacular debut on the New York scene thanks to Stieglitz. An artist trained as an engineer, he felt comfortable with mechanical tools used in art: “If only people would broaden their concepts to include concern about the brotherhood of man and the machine, the world would be a great deal better.”

Photography developed new ways of documenting reality and invited people to see things that they had never before imagined. The result was a remarkable expansion of visual horizons. Now digital photography, together with software such as Adobe Photoshop, which allows the user to embellish, distort and transform any image at will, offers new ways to document reality or to create virtual worlds. Instagram, an online photo-sharing app, has fostered a worldwide competition to take the best pictures.

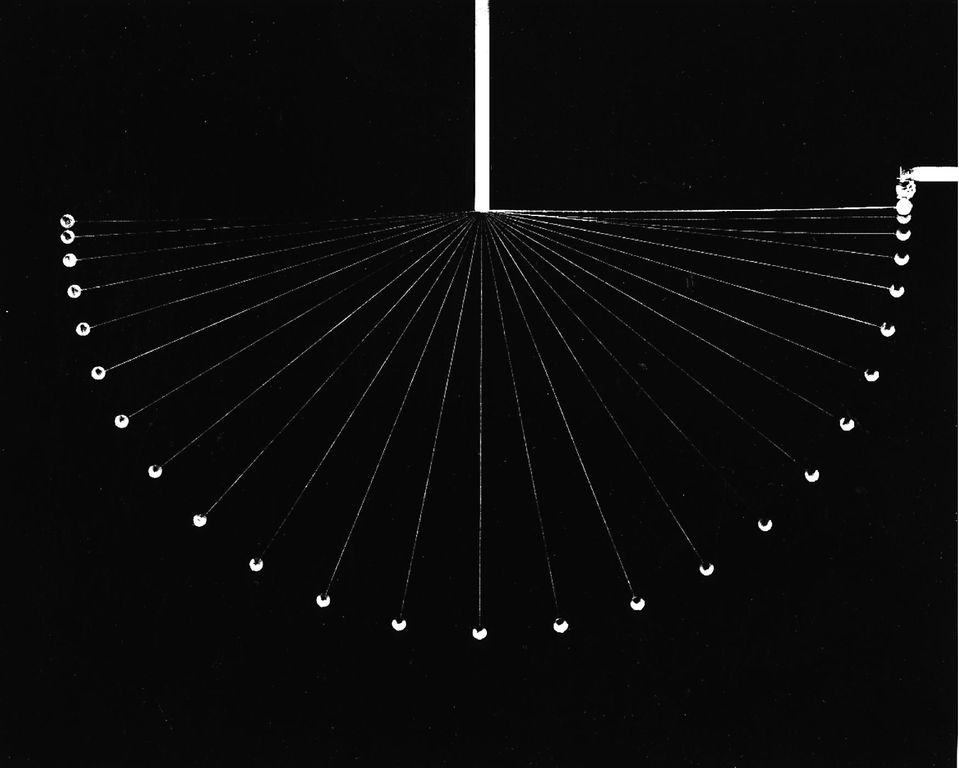

Transformation of Energy, Berenice Abbott, Cambridge, Massachusetts, c. 1958

This photograph by Abbott was aimed at illustrating the laws of physics. The image is scientific in intent and aesthetic in effect.

In reaction to the machine age, the Arts and Crafts movement in England, calling for a revival of nature and individual expression, had an extraordinary impact on graphic design; it was followed by the development on the continent of Art Nouveau.

The latter decorative style, with plant and animal motifs stylized in the extreme, was, to some extent, an artistic commentary on Darwinism (Darwin as it happens also published work on plant morphogenesis). The style later developed a geometric phase that reflected the changing relationship with space.

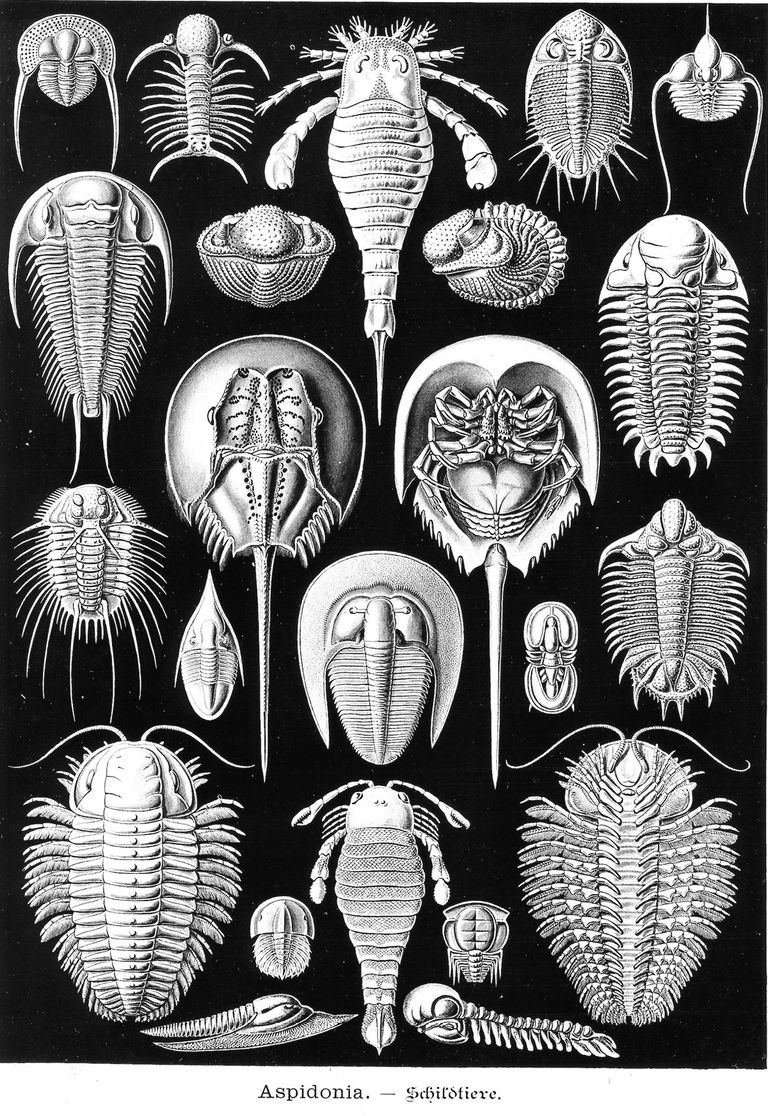

Trilobites, eurypterids and horseshoe crabs, Ernst Haeckel, c. 1904

Haeckel was the first German biologist to become an ardent Darwin partisan and the first to use the word “ecology.” The connection between his plant and animal drawings and the rise of Art Nouveau is evident. His work fascinated artists such as Gallé, Guimard and Mucha.

A new approach advocated that all branches of art, from graphics to painting, and from sculpture to design, shared values expressed by mass-produced quality goods. The German Bauhaus school, for example, invested its creative energy in “total design,” implicitly recognizing the common roots of fine and applied arts.

Cubists, Futurists and Constructivists worked in parallel with philosophers and poets. The need to harmonize all facets of life was stressed by the writer Aldous Huxley (1894–1963): “It is obvious that the machine is here to stay. Whole armies of Morrises and Tolstoys could not now expel it. Let us exploit them to create beauty—a modern beauty while we are about it.”

Democracy logo, Jerzy Janiszewsky, Poland, 1980

Machines literally flooded the world with information; communicating masses of messages to culturally diverse audiences through simple symbols became the norm. In this context, a kind of graphic Esperanto was designed by Otto Neurath (1882–1945), a Viennese philosopher with a passion for hieroglyphs. His modern pictographs became the prototypes for international signage: the “world language without words” spread around the globe.

Design is now applied to everything from typefaces to fashion and home furnishings. International events of any kind require an identity, or a logo. Design is obviously not a modern invention but the mass media have turned it into a global phenomenon.

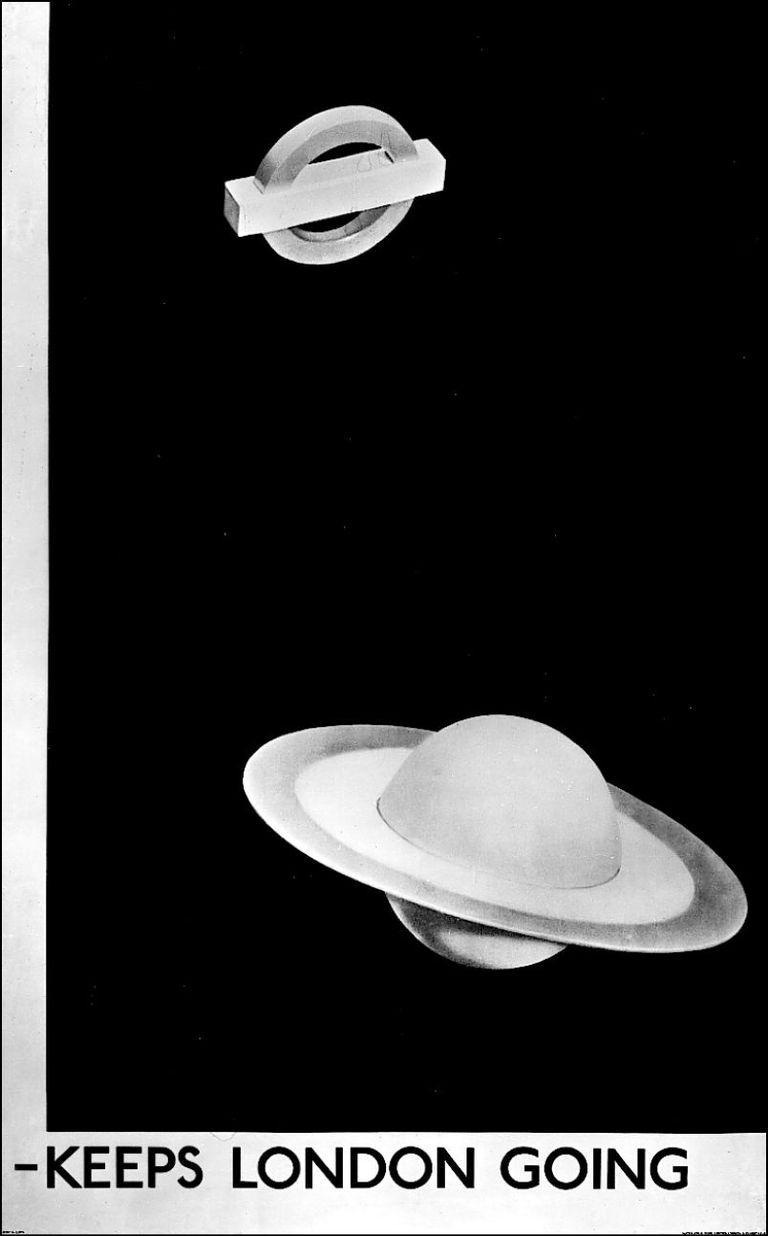

Keeps London Going, Man Ray, 1932

Man Ray, who “painted with light,” enlarged the range of photographic media by creating solarizations and “rayographs.” He discovered the latter technique by chance, having left small objects such as keys and cotton on photographic paper which produced mysteriously poetic images. This poster designed for the London underground is based on the similarity of its symbol to the planet Saturn.

Offset lithograph printed in color, 395⁄8 × 241⁄4 in. (100.6 × 61.6 cm)

Museum of Modern Art, New York; Gift of Bernard Davis, 178.1950

While photocopying machines greatly accelerated the spread of information and images, and even generated “copyart,” computers and networks effectively engaged the most disparate cultures in dialogue.

With satellites, works of art in remote museums and scientific data in distant laboratories are instantly accessible. The interactive technologies, synthesizing sound and picture, are burgeoning fields of endeavor where the public is often informed before the specialists!

It can hardly be a coincidence that Douglas Hofstadter, an expert in artificial intelligence, had revealed in the 1960s a profound interest in aesthetics. His Pulitzer prizewinning book, Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, which is devoted to the correspondences between mathematics, graphic art and music, demonstrates how systems can be expressed either as theorems, drawings or musical notes.

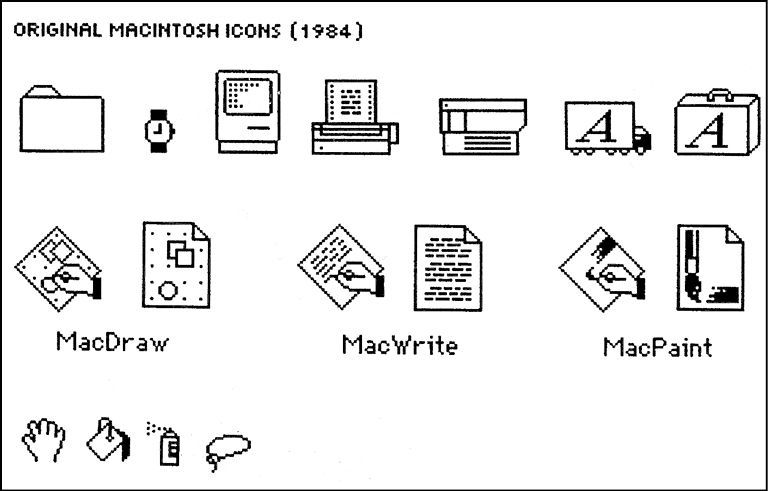

Icons created for the 128K Macintosh computer, Susan Kare and Bill Adkins, 1984

Design of bankcards or computer icons requires the collaboration of a wide variety of experts: economists and sociologists as well as artists and technologists.

Even though artificial intelligence has greatly advanced, it is still in its infancy; where creativity is concerned, computer intelligence cannot compete with the complex functioning of a young child’s brain. It is difficult to guess what is coming next, however. Computers already recognize voices and may well make the keyboard obsolete … will writing still be needed?

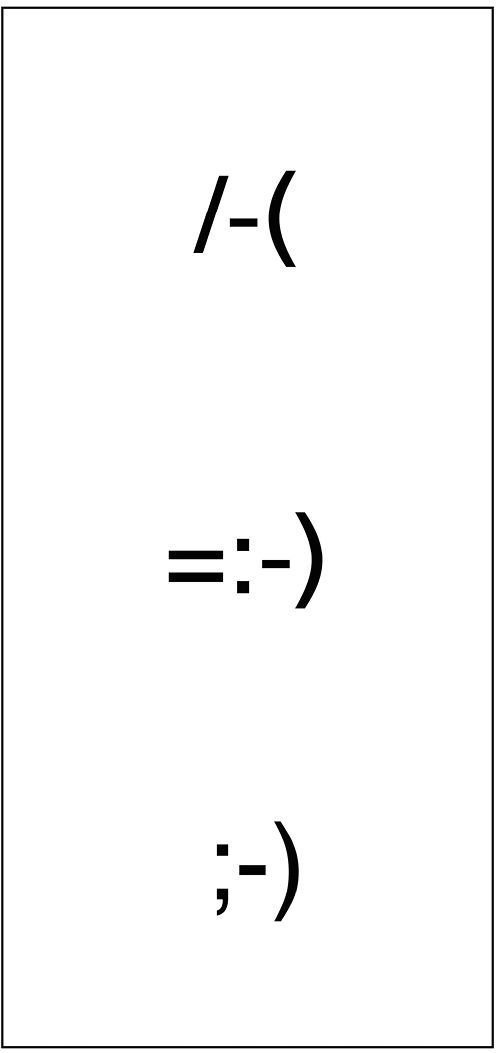

“Emoticons” used by cybersurfers

The language used on the Internet resembles ancient pictograms. Reading from top to bottom: rather than being angry, I express my joy … and send you a “wink.”

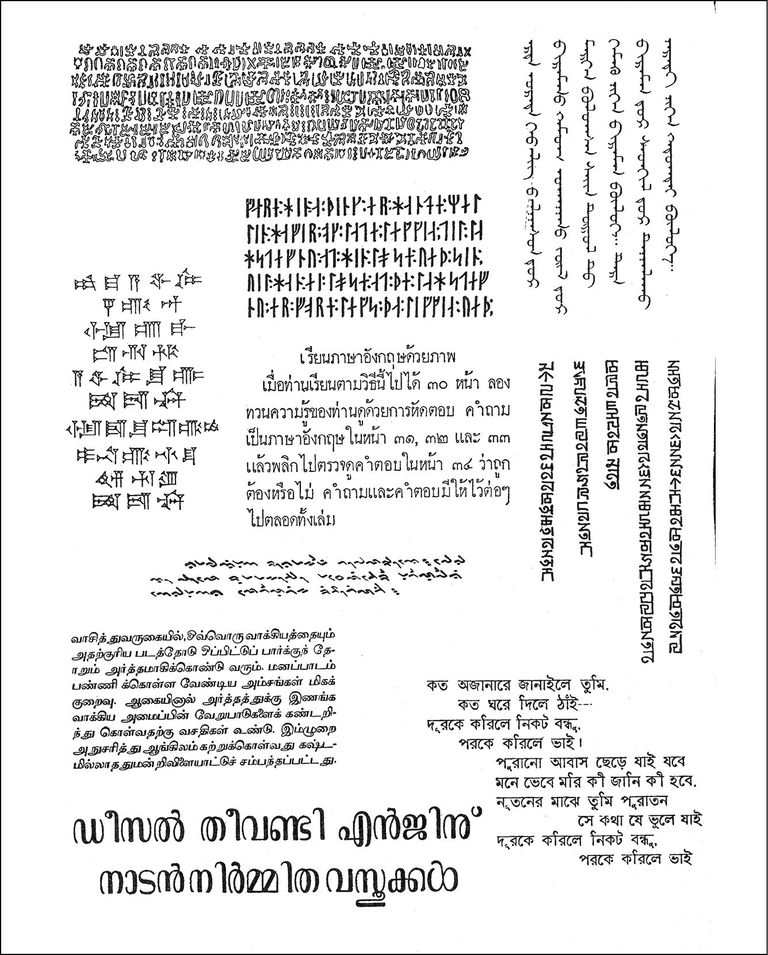

Collage of scripts, Douglas Hofstadter

Hofstadter said of the above languages: “As an outsider, I feel a deep sense of mystery as I wonder how meaning is cloaked in the strange curves and angles of each of these beautiful aperiodic crystals. In form there is content.”

Surfing on the Web and playing with DVDs (digital versatile disks) which can store as much data as several CD-ROMs (compact disk read-only memory) structure thought in such a way that one can travel freely within a huge body of knowledge. This perhaps signals a move away from the linear thinking that was painstakingly developed over the past five hundred years.

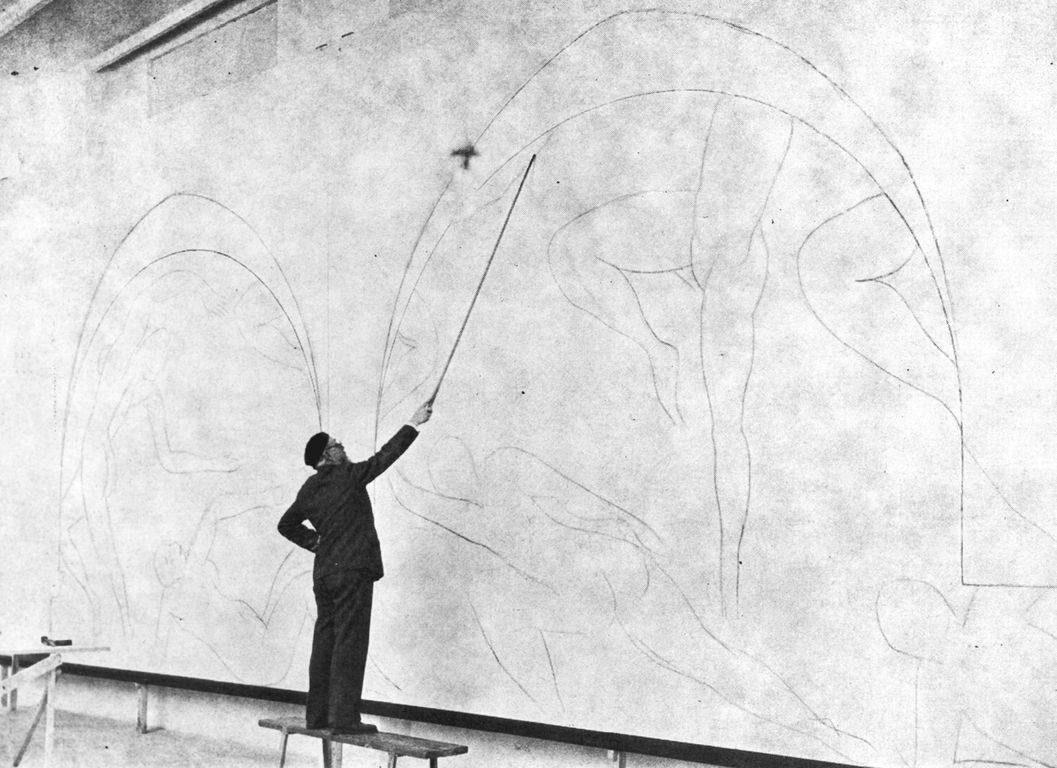

Matisse drawing a panel of the Dance, 1931

One version of the Dance was created for a specific setting in the home of Albert Barnes, American collector and arts patron. After almost a full year’s work, Matisse had to begin again because he had been using the wrong measurements. Computers would have greatly expedited the recalibrating process. The art of Matisse, the “genius of omission,” for whom each line or space occupies a highly specific place, has a metrical character.

Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia

We have entered a new millennium with as many questions as our nineteenth-century forebears raised when Darwin formulated his theory of evolution; painters bade farewell to conventional representation and beauty as the ultimate aims of art. What is more, in the eighteenth century, machines were already expected to replace humanity … yet we are still here.

Since the dawn of civilization, artists and scientists have mutually contributed to the cause of visual communication. From abstract, pictorially imaginative writing systems to illuminated manuscripts, all of which were displaced by printing, to photography and computer technology, art and science have been inseparable.

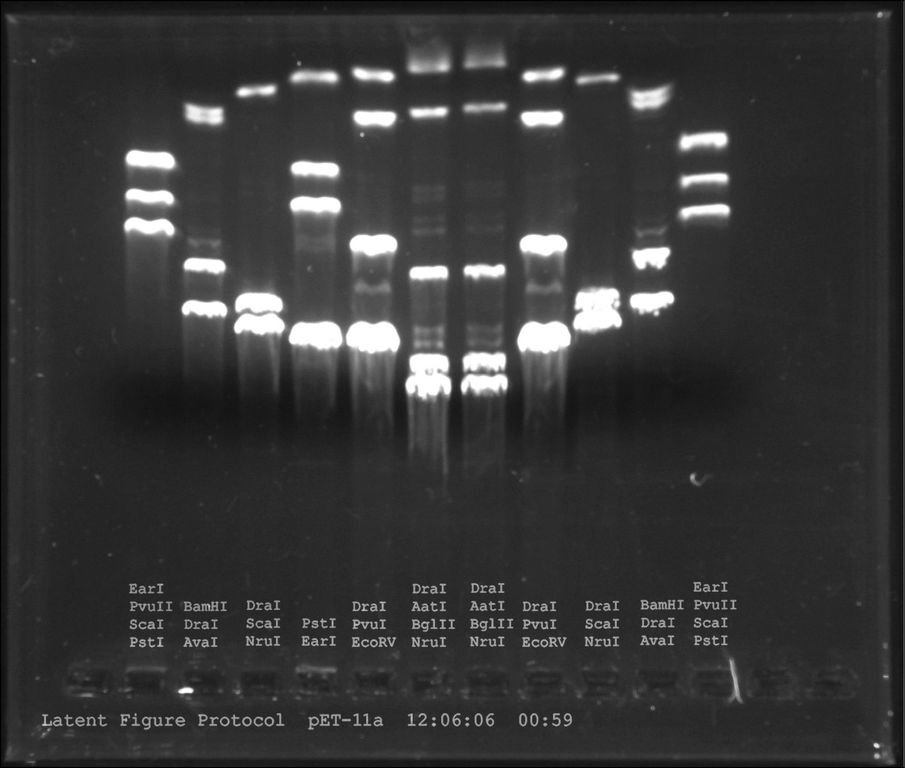

Latent Figure Protocol, Paul Vanouse, 2006

The artist manipulated the movement of DNA fragments through an electrically charged gel in order to produce an image of the copyright symbol. (Biologists more typically use this technique, known as electrophoresis, to analyze the size of DNA molecules.) Here the copyright symbol is meant to evoke contemporary ethical debates over genetic patents and other ownership claims on living things.