The chart patterns covered in this chapter are called continuation patterns. These patterns usually indicate that the sideways price action on the chart is nothing more than a pause in the prevailing trend, and that the next move will be in the same direction as the trend that preceded the formation. This distinguishes this group of patterns from those in the previous chapter, which usually indicate that a major trend reversal is in progress.

Another difference between reversal and continuation patterns is their time duration. Reversal patterns usually take much longer to build and represent major trend changes. Continuation patterns, on the other hand, are usually shorter term in duration and are more accurately classified as near term or intermediate patterns.

Notice the constant use of the term “usually.” The treatment of all chart patterns deals of necessity with general tendencies as opposed to rigid rules. There are always exceptions. Even the grouping of price patterns into different categories sometimes becomes tenuous. Triangles are usually continuation patterns, but sometimes act as reversal patterns. Although triangles are usually considered intermediate patterns, they may occasionally appear on long term charts and take on major trend significance. A variation of the triangle—the inverted variety—usually signals a major market top. Even the head and shoulders pattern, the best known of the major reversal patterns, will on occasion be seen as a consolidation pattern.

Even with allowances for a certain amount of ambiguity and the occasional exception, chart patterns do generally fall into the above two categories and, if properly interpreted, can help the chartist determine what the market will probably do most of the time

Let’s begin our treatment of continuation patterns with the triangle. There are three types of triangles—symmetrical, ascending, and descending. (Some chartists include a fourth type of triangle known as an expanding triangle, or broadening formation. This is treated as a separate pattern later.) Each type of triangle has a slightly different shape and has different forecasting implications.

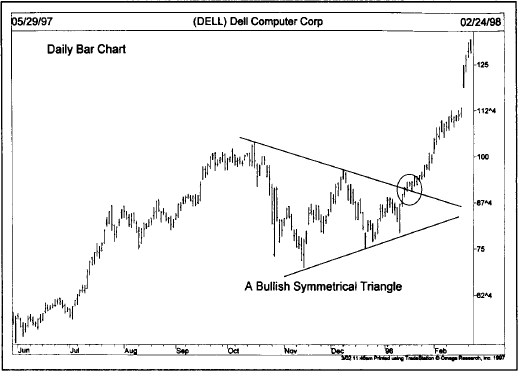

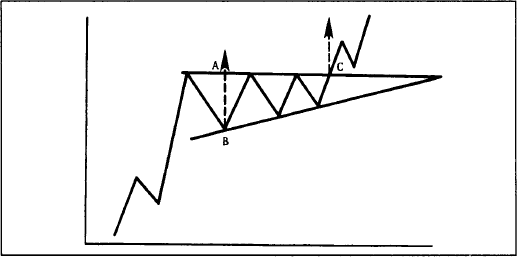

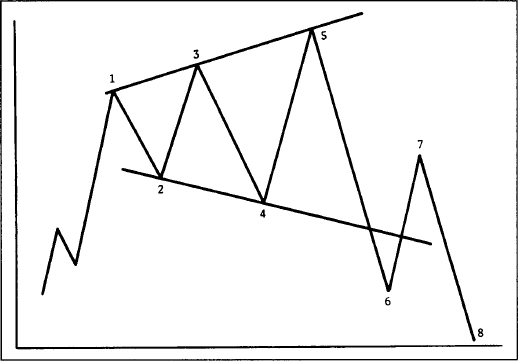

Figures 6.1a-c show examples of what each triangle looks like. The symmetrical triangle (see Figure 6.1a) shows two converging trendlines, the upper line descending and the lower line ascending. The vertical line at the left, measuring the height of the pattern, is called the base. The point of intersection at the right, where the two lines meet, is called the apex. For obvious reasons, the symmetrical triangle is also called a coil.

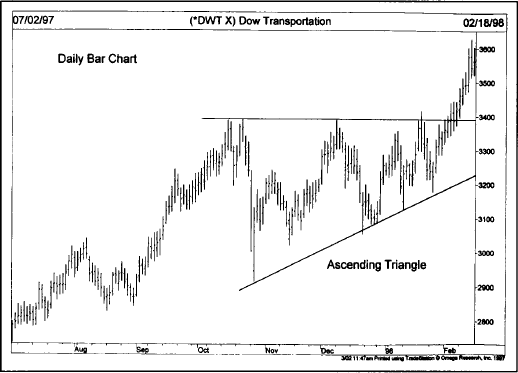

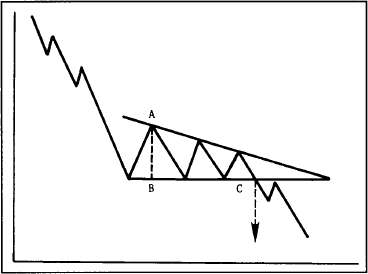

The ascending triangle has a rising lower line with a flat or horizontal upper line (see Figure 6.1b). The descending triangle (Figure 6.1c), by contrast, has the upper line declining with a flat or horizontal bottom line. Let’s see how each one is interpreted.

Figure 6.1a Example of a bullish symmetrical triangle. Notice the two converging trendlines. A close outside either trendline completes the pattern. The vertical line at the left is the base. The point at the right where the two lines meet is the apex.

Figure 6.1b Example of an ascending triangle. Notice the flat upper line and the rising lower line. This is generally a bullish pattern.

Figure 6.1c Example of a descending triangle. Notice the flat bottom line and the declining upper line. This is usually a bearish pattern.

The symmetrical triangle (or the coil) is usually a continuation pattern. It represents a pause in the existing trend after which the original trend is resumed. In the example in Figure 6.1a, the prior trend was up, so that the percentages favor resolution of the triangular consolidation on the upside. If the trend had been down, then the symmetrical triangle would have bearish implications.

The minimum requirement for a triangle is four reversal points. Remember that it always takes two points to draw a trendline. Therefore, in order to draw two converging trendlines, each line must be touched at least twice. In Figure 6.1a, the triangle actually begins at point 1, which is where the consolidation in the uptrend begins. Prices pull back to point 2 and then rally to point 3. Point 3, however, is lower than point 1. The upper trendline can only be drawn once prices have declined from point 3.

Notice that point 4 is higher than point 2. Only when prices have rallied from point 4 can the lower upslanting line be drawn. It is at this point that the analyst begins to suspect the he or she is dealing with the symmetrical triangle. Now there are four reversal points (1, 2, 3, and 4) and two converging trendlines.

While the minimum requirement is four reversal points, many triangles have six reversal points as shown in Figure 6.1a.

This means that there are actually three peaks and three troughs that combine to form five waves within the triangle before the uptrend resumes. (When we get to the Elliott Wave Theory, we’ll have more to say about the five wave tendency within triangles.)

There is a time limit for the resolution of the pattern, and that is the point where the two lines meet—at the apex. As a general rule, prices should break out in the direction of the prior trend somewhere between two-thirds to three-quarters of the horizontal width of the triangle. That is, the distance from the vertical base on the left of the pattern to the apex at the far right. Because the two lines must meet at some point, that time distance can be measured once the two converging lines are drawn. An upside breakout is signaled by a penetration of the upper trendline. If prices remain within the triangle beyond the three-quarters point, the triangle begins to lose its potency, and usually means that prices will continue to drift out to the apex and beyond

The triangle, therefore, provides an interesting combination of price and time. The converging trendlines give the price boundaries of the pattern, and indicate at what point the pattern has been completed and the trend resumed by the penetration of the upper trendline (in the case of an uptrend). But these trendlines also provide a time target by measuring the width of the pattern. If the width, for example, were 20 weeks long, then the breakout should take place sometime between the 13th and the 15th week. (See Figure 6.1d.)

The actual trend signal is given by a closing penetration of one of the trendlines. Sometimes a return move will occur back to the penetrated trendline after the breakout. In an uptrend, that line has become a support line. In a downtrend, the lower line becomes a resistance line once it’s broken. The apex also acts as an important support or resistance level after the breakout occurs. Various penetration criteria can be applied to the breakout, similar to those covered in the previous two chapters. A minimum penetration criterion would be a closing price outside the trendline and not just an intraday penetration.

Figure 6.1d Dell formed a bullish symmetrical triangle during the fourth quarter of 1997. Measured from left to right, the triangle width is 18 weeks. Prices broke out on the 13th week (see circle), just beyond the two-thirds point.

Volume should diminish as the price swings narrow within the triangle. This tendency for volume to contract is true of all consolidation patterns. But the volume should pick up noticeably at the penetration of the trendline that completes the pattern. The return move should be on light volume with heavier activity again as the trend resumes.

Two other points should be mentioned about volume. As is the case with reversal patterns, volume is more important on the upside than on the downside. An increase in volume is essential to the resumption of an uptrend in all consolidation patterns.

The second point about volume is that, even though trading activity diminishes during formation of the pattern, a close inspection of the volume usually gives a clue as to whether the heavier volume is occurring during the upmoves or down-moves. In an uptrend, for example, there should be a slight tendency for volume to be heavier during the bounces and lighter on the price dips.

Triangles have measuring techniques. In the case of the symmetrical triangle, there are a couple of techniques generally used. The simplest technique is to measure the height of the vertical line at the widest part of the triangle (the base) and measure that distance from the breakout point. Figure 6.2 shows the distance projected from the breakout point, which is the technique I prefer.

The second method is to draw a trendline from the top of the base (at point A) parallel to the lower trendline. This upper channel line then becomes the upside target in an uptrend. It is possible to arrive at a rough time target for prices to meet the upper channel line. Prices will sometimes hit the channel line at the same time the two converging lines meet at the apex.

Figure 6.2 There are two ways to take a measurement from a symmetrical triangle. One is to measure the height of the base (AB); project that vertical distance from the breakout point at C. Another method is to draw a parallel line upward from the top of the baseline (A) parallel to the lower line in the triangle.

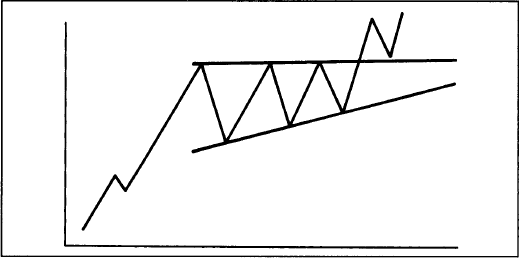

The ascending and descending triangles are variations of the symmetrical, but have different forecasting implications. Figures 6.3a and b show examples of an ascending triangle. Notice that the upper trendline is flat, while the lower line is rising. This pattern indicates that buyers are more aggressive than sellers. It is considered a bullish pattern and is usually resolved with a breakout to the upside.

Both the ascending and descending triangles differ from the symmetrical in a very important sense. No matter where in the trend structure the ascending or descending triangles appear, they have very definite forecasting implications. The ascending triangle is bullish and the descending triangle is bearish. The symmetrical triangle, by contrast, is inherently a neutral pattern. This does not mean, however, that the symmetrical triangle does not have forecasting value. On the contrary, because the symmetrical triangle is a continuation pattern, the analyst must simply look to see the direction of the previous trend and then make the assumption that the previous trend will continue.

Figure 6.3a An ascending triangle. The pattern is completed on a decisive close above the upper line. This breakout should see a sharp increase in volume. That upper resistance line should act as support on subsequent dips after the breakout. The minimum price objective is obtained by measuring the height of the triangle (AB) and projecting that distance upward from the breakout point at C.

Figure 6.3b The Dow Transports formed a bullish ascending triangle near the end of 1997. Notice the flat upper line at 3400 and the rising lower line. This is normally a bullish pattern no matter where it appears on the chart.

Let’s get back to the ascending triangle. As already stated, more often than not, the ascending triangle is bullish. The bullish breakout is signaled by a decisive closing above the flat upper trendline. As in the case of all valid upside breakouts, volume should see a noticeable increase on the breakout. A return move back to the support line (the flat upper line) is not unusual and should take place on light volume.

The measuring technique for the ascending triangle is relatively simple. Simply measure the height of the pattern at its widest point and project that vertical distance from the breakout point. This is just another example of using the volatility of a price pattern to determine a minimum price objective.

While the ascending triangle most often appears in an uptrend and is considered a continuation pattern, it sometimes appears as a bottoming pattern. It is not unusual toward the end of a downtrend to see an ascending triangle develop. However, even in this situation, the interpretation of the pattern is bullish. The breaking of the upper line signals completion of the base and is considered a bullish signal. Both the ascending and descending triangles are sometimes also referred to as right angle triangles.

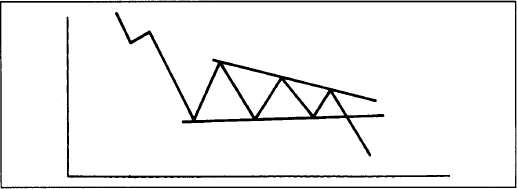

The descending triangle is just a mirror image of the ascending, and is generally considered a bearish pattern. Notice in Figures 6.4a and b the descending upper line and the flat lower line. This pattern indicates that sellers are more aggressive than buyers, and is usually resolved on the downside. The downside signal is registered by a decisive close under the lower trendline, usually on increased volume. A return move sometimes occurs which should encounter resistance at the lower trendline.

The measuring technique is exactly the same as the ascending triangle in the sense that the analyst must measure the height of the pattern at the base to the left and then project that distance down from the breakdown point.

While the descending triangle is a continuation pattern and usually is found within downtrends, it is not unusual on occasion for the descending triangle to be found at market tops. This type of pattern is not that difficult to recognize when it does appear in the top setting. In that case, a close below the flat lower line would signal a major trend reversal to the downside.

Figure 6.4a A descending triangle. The bearish pattern is completed with a decisive close under the lower flat line. The measuring technique is the height of the triangle (AB) projected down from the breakout at point C.

Figure 6.4b A bearish descending triangle formed in Du Pont during the autumn of 1997. The upper line is descending while the lower line is flat. The break of the lower line in early October resolved the pattern to the downside.

The volume pattern in both the ascending and descending triangles is very similar in that the volume diminishes as the pattern works itself out and then increases on the breakout. As in the case of the symmetrical triangle, during the formation the chartist can detect subtle shifts in the volume pattern coinciding with the swings in the price action. This means that in the ascending pattern, the volume tends to be slightly heavier on bounces and lighter on dips. In the descending formation, volume should be heavier on the downside and lighter during the bounces.

One final factor to be considered on the subject of triangles is that of the time dimension. The triangle is considered an intermediate pattern, meaning that it usually takes longer than a month to form, but generally less than three months. A triangle that lasts less than a month is probably a different pattern, such as a pennant, which will be covered shortly. As mentioned earlier, triangles sometimes appear on long term price charts, but their basic meaning is always the same.

This next price pattern is an unusual variation of the triangle and is relatively rare. It is actually an inverted triangle or a triangle turned backwards. All of the triangular patterns examined so far show converging trendlines. The broadening formation, as the name implies, is just the opposite. As the pattern in Figure 6.5 shows, the trendlines actually diverge in the broadening formation, creating a picture that looks like an expanding triangle. It is also called a megaphone top.

The volume pattern also differs in this formation. In the other triangular patterns, volume tends to diminish as the price swings grow narrower. Just the opposite happens in the broadening formation. The volume tends to expand along with the wider price swings. This situation represents a market that is out of control and unusually emotional. Because this pattern also represents an unusual amount of public participation, it most often occurs at major market tops. The expanding pattern, therefore, is usually a bearish formation. It generally appears near the end of a major bull market.

Figure 6.5 A broadening top. This type of expanding triangle usually occurs at major tops. It shows three successively higher peaks and two declining troughs. The violation of the second trough completes the pattern. This is an unusually difficult pattern to trade and fortunately is relatively rare.

The flag and pennant formations are quite common. They are usually treated together because they are very similar in appearance, tend to show up at about the same place in an existing trend, and have the same volume and measuring criteria.

The flag and pennant represent brief pauses in a dynamic market move. In fact, one of the requirements for both the flag and the pennant is that they be preceded by a sharp and almost straight line move. They represent situations where a steep advance or decline has gotten ahead of itself, and where the market pauses briefly to “catch its breath” before running off again in the same direction.

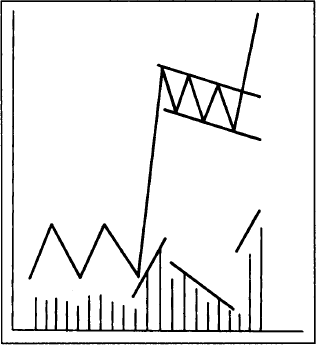

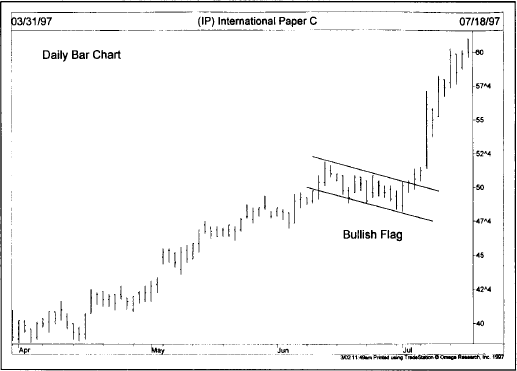

Flags and pennants are among the most reliable of continuation patterns and only rarely produce a trend reversal. Figures 6.6a-b show what these two patterns look like. To begin with, notice the steep price advance preceding the formations on heavy volume. Notice also the dramatic drop off in activity as the consolidation patterns form and then the sudden burst of activity on the upside breakout.

The construction of the two patterns differs slightly. The flag resembles a parallelogram or rectangle marked by two parallel trendlines that tend to slope against the prevailing trend. In a downtrend, the flag would have a slight upward slope.

Figure 6.6a Example of a bullish flag. The flag usually occurs after a sharp move and represents a brief pause in the trend. The flag should slope against the trend. Volume should dry up during the formation and build again on the breakout. The flag usually occurs near the midpoint of the move.

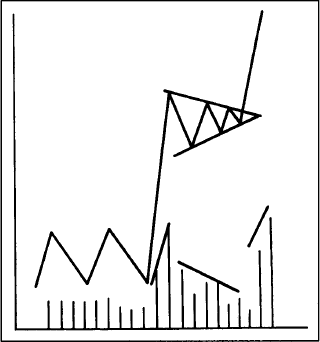

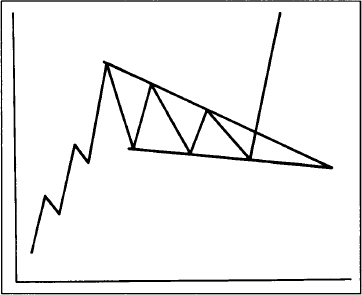

Figure 6.6b A bullish pennant. Resembles a small symmetrical triangle, but usually lasts no longer than three weeks. Volume should be light during its formation. The move after the pennant is completed should duplicate the size of the move preceding it.

The pennant is identified by two converging trendlines and is more horizontal. It very closely resembles a small symmetrical triangle. An important requirement is that volume should dry up noticeably while each of the patterns is forming.

Both patterns are relatively short term and should be completed within one to three weeks. Pennants and flags in downtrends tend to take even less time to develop, and often last no longer than one or two weeks. Both patterns are completed on the penetration of the upper trendline in an uptrend. The breaking of the lower trendline would signal resumption of downtrends. The breaking of those trendlines should take place on heavier volume. As usual, upside volume is more critically important than downside volume. (See Figures 6.7a-b.)

The measuring implications are similar for both patterns. Flags and pennants are said to “fly at half-mast” from a flagpole. The flagpole is the prior sharp advance or decline. The term “half-mast” suggests that these minor continuation patterns tend to appear at about the halfway point of the move. In general, the move after the trend has resumed will duplicate the flagpole or the move just prior to the formation of the pattern.

Figure 6.7a A bullish flag in International Paper. The flag looks like a down-sloping parallelogram. Notice that the flag occurred right at the halfway point of the uptrend.

To be more precise, measure the distance of the preceding move from the original breakout point. That is to say, the point at which the original trend signal was given, either by the penetration of a support or resistance level or an important trendline. That vertical distance of the preceding move is then measured from the breakout point of the flag or pennant—that is, the point at which the upper line is broken in an uptrend or the lower line in a downtrend.

Let’s summarize the more important points of both patterns.

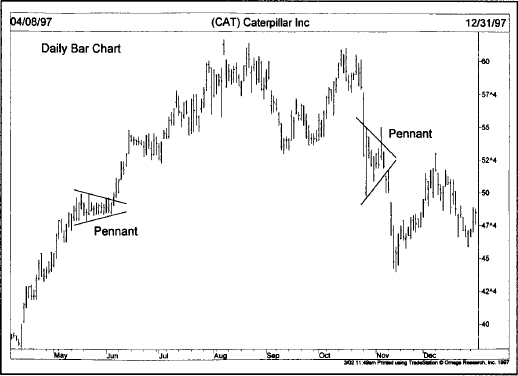

Figure 6.7b A couple of pennants are flying on this Caterpillar chart. Pennants are short term continuation patterns that look like small symmetrical triangles. The pennant to the left continued the uptrend, while the one to the right continued the downtrend.

The wedge formation is similar to a symmetrical triangle both in terms of its shape and the amount of time it takes to form. Like the symmetrical triangle, it is identified by two converging trendlines that come together at an apex. In terms of the amount of time it takes to form, the wedge usually lasts more than one month but not more than three months, putting it into the intermediate category.

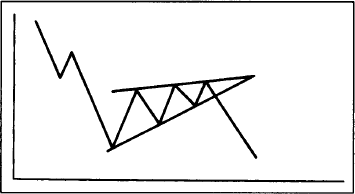

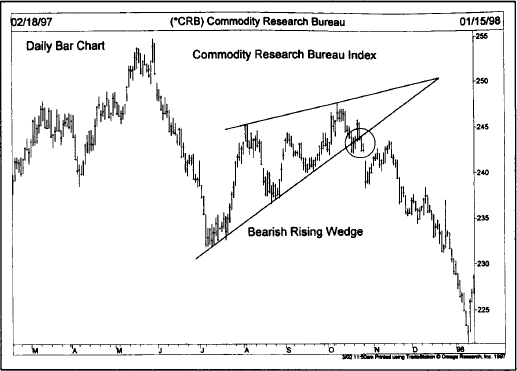

What distinguishes the wedge is its noticeable slant. The wedge pattern has a noticeable slant either to the upside or the downside. As a rule, like the flag pattern, the wedge slants against the prevailing trend. Therefore, a falling wedge is considered bullish and a rising wedge is bearish. Notice in Figure 6.8a that the bullish wedge slants downward between two converging trendlines. In the downtrend in Figure 6.8b, the converging trendlines have an unmistakable upward slant.

Figure 6.8a Example of a bullish falling wedge. The wedge pattern has two converging trendlines, but slopes against the prevailing trend. A falling wedge is usually bullish.

Figure 6.8b Example of a bearish wedge. A bearish wedge should slope upward against the prevailing downtrend.

Wedges show up most often within the existing trend and usually constitute continuation patterns. The wedge can appear at tops or bottoms and signal a trend reversal. But that type of situation is much less common. Near the end of an uptrend, the chartist may observe a clearcut rising wedge. Because a continuation wedge in an uptrend should slope downward against the prevailing trend, the rising wedge is a clue to the chartist that this is a bearish and not a bullish pattern. At bottoms, a falling wedge would be a tip-off of a possible end of a bear trend.

Whether the wedge appears in the middle or the end of a market move, the market analyst should always be guided by the general maxim that a rising wedge is bearish and a falling wedge is bullish. (See Figure 6.8c.)

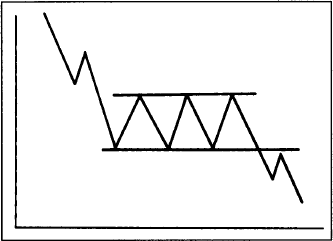

The rectangle formation often goes by other names, but is usually easy to spot on a price chart. It represents a pause in the trend during which prices move sideways between two parallel horizontal lines. (See Figures 6.9a-c.)

The rectangle is sometimes referred to as a trading range or a congestion area. In Dow Theory parlance, it is referred to as a line. Whatever it is called, it usually represents just a consolidation period in the existing trend, and is usually resolved in the direction of the market trend that preceded its occurrence. In terms of forecasting value, it can be viewed as being similar to the symmetrical triangle but with flat instead of converging trendlines.

Figure 6.8c Example of a bearish rising wedge. The two converging trendlines have a definite upward slant. The wedge slants against the prevailing trend. Therefore, a rising wedge is bearish, and a falling wedge is bullish.

Figure 6.9a Example of a bullish rectangle in an uptrend. This pattern is also called a trading range, and shows prices trading between two horizontal trendlines. It is also called a congestion area.

Figure 6.9b Example of a bearish rectangle. While rectangles are usually considered continuation patterns, the trader must always be alert for signs that it may turn into a reversal pattern, such as a triple bottom.

Figure 6.9c A bullish rectangle. Compaq’s uptrend was interrupted for four months while it traded sideways. The break above the upper line in early May completed the pattern and resumed the uptrend. Rectangles are usually continuation patterns.

A decisive close outside either the upper or lower boundary signals completion of the rectangle and points the direction of the trend. The market analyst must always be on the alert, however, that the rectangular consolidation does not turn into a reversal pattern. In the uptrend shown in Figure 6.9a, for example, notice that the three peaks might initially be viewed as a possible triple top reversal pattern.

One important clue to watch for is the volume pattern. Because the price swings in both directions are fairly broad, the analyst should keep a close eye on which moves have the heavier volume. If the rallies are on heavier and the setbacks on lighter volume, then the formation is probably a continuation in the uptrend. If the heavier volume is on the downside, then it can be considered a warning of a possible trend reversal in the works.

Some chartists trade the swings within such a pattern by buying dips near the bottom and selling rallies near the top of the range. This technique enables the short term trader to take advantage of the well defined price boundaries, and profit from an otherwise trendless market. Because the positions are being taken at the extremes of the range, the risks are relatively small and well defined. If the trading range remains intact, this countertrend trading approach works quite well. When a breakout does occur, the trader not only exits the last losing trade immediately, but can reverse the previous position by initiating a new trade in the direction of the new trend. Oscillators are especially useful in sideways trading markets, but less useful once the breakout has occurred for reasons discussed in Chapter 10.

Other traders assume the rectangle is a continuation pattern and take long positions near the lower end of the price band in an uptrend, or initiate short positions near the top of the range in downtrends. Others avoid such trendless markets altogether and await a clearcut breakout before committing their funds. Most trend-following systems perform very poorly during these periods of sideways and trendless market action.

In terms of duration, the rectangle usually falls into the one to three month category, similar to triangles and wedges. The volume pattern differs from other continuation patterns in the sense that the broad price swings prevent the usual dropoff in activity seen in other such patterns.

The most common measuring technique applied to the rectangle is based on the height of the price range. Measure the height of the trading range, from top to bottom, and then project that vertical distance from the breakout point. This method is similar to the other vertical measuring techniques already mentioned, and is based on the volatility of the market. When we cover the count in point and figure charting, we’ll say more on the question of horizontal price measurements.

Everything mentioned so far concerning volume on breakouts and the probability of return moves applies here as well. Because the upper and lower boundaries are horizontal and so well defined in the rectangle, support and resistance levels are more clearly evident. This means that, on upside breakouts, the top of the former price band should now provide solid support on any selloffs. After a downside breakout in downtrends, the bottom of the trading range (the previous support area) should now provide a solid ceiling over the market on any rally attempts.

The measured move, or the swing measurement as it is sometimes called, describes the phenomenon where a major market advance or decline is divided into two equal and parallel moves, as shown in Figure 6.10a. For this approach to work, the market moves should be fairly orderly and well defined. The measured move is really just a variation of some of the techniques we’ve already touched on. We’ve seen that some of the consolidation patterns, such as flags and pennants, usually occur at about the halfway point of a market move. We’ve also mentioned the tendency of markets to retrace about a third to a half of a prior trend before resuming that trend.

Figure 6.10a Example of a measured move (or the swing measurement) in an uptrend. This theory holds that the second leg in the advance (CD) duplicates the size and slope of the first upleg (AB). The corrective wave (BC) often retraces a third to a half of AB before the uptrend is resumed.

Figure 6.10b A measured move takes the prior upleg (AB) and adds that value to the bottom of the correction at C. On this chart, the prior uptrend (AB) was 20 points. Adding that to the lowpoint at C (62) yielded a price target to 82 (D).

In the measured move, when the chartist sees a well-defined situation, such as in Figure 6.10a, with a rally from point A to point B followed by a countertrend swing from point B to point C (which retraces a third to a half of wave AB), it is assumed that the next leg in the uptrend (CD) will come close to duplicating the first leg (AB). The height of wave (AB), therefore, is simply measured upward from the bottom of the correction at point C.

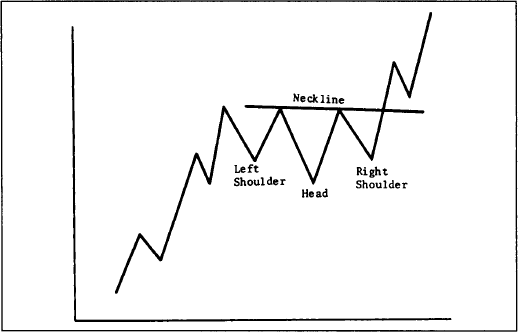

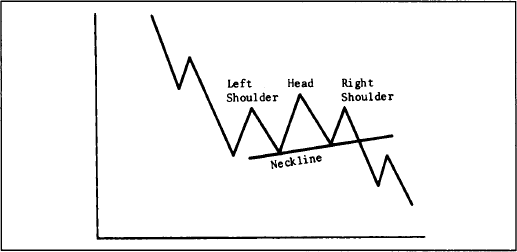

In the previous chapter, we treated the head and shoulders pattern at some length and described it as the best known and most trustworthy of all reversal patterns. The head and shoulders pattern can sometimes appear as a continuation instead of a reversal pattern.

In the continuation head and shoulders variety, prices trace out a pattern that looks very similar to a sideways rectangular pattern except that the middle trough in an uptrend (see Figure 6.11a) tends to be lower than either of the two shoulders. In a downtrend (see Figure 6.11b), the middle peak in the consolidation exceeds the other two peaks. The result in both cases is a head and shoulders pattern turned upside down. Because it is turned upside down, there is no chance of confusing it with the reversal pattern.

Figure 6.11a Example of a bullish continuation head and shoulders pattern.

Figure 6.11b Example of a bearish continuation head and shoulders pattern.

Figure 6.11c General Motors formed a continuation head and shoulders pattern during the first half of 1997. The pattern is very clear but shows up in an unusual place. The pattern was completed and the uptrend resumed with the close above the neckline at 60.

The principle of confirmation is one of the common themes running throughout the entire subject of market analysis, and is used in conjunction with its counterpart—divergence. We’ll introduce both concepts here and explain their meaning, but we’ll return to them again and again throughout the book because their impact is so important. We’re discussing confirmation here in the context of chart patterns, but it applies to virtually every aspect of technical analysis. Confirmation refers to the comparison of all technical signals and indicators to ensure that most of those indicators are pointing in the same direction and are confirming one another.

Divergence is the opposite of confirmation and refers to a situation where different technical indicators fail to confirm one another. While it is being used here in a negative sense, divergence is a valuable concept in market analysis, and one of the best early warning signals of impending trend reversals. We’ll discuss the principle of divergence at greater length in Chapter 10, “Oscillators and Contrary Opinion.”

This concludes our treatment of price patterns. We stated earlier that the three pieces of raw data used by the technical analyst were price, volume, and open interest. Most of what we’ve said so far has focused on price. Let’s take a closer look now at volume and open interest and how they are incorporated into the analytical process.