NEXT DAY THE PICTURE of Mr. Popper and Captain Cook appeared in the Stillwater Morning Chronicle, with a paragraph about the house painter who had received a penguin by air express from Admiral Drake in the faraway Antarctic. Then the Associated Press picked up the story, and a week later the photograph, in rotogravure, could be seen in the Sunday edition of the most important newspapers in all the large cities in the country.

Naturally the Poppers all felt very proud and happy.

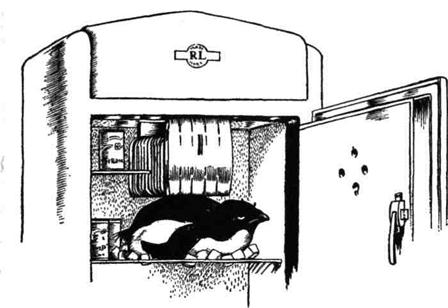

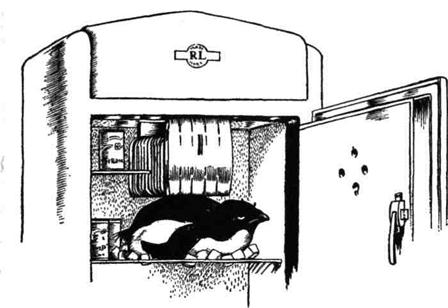

Captain Cook was not happy, however. He had suddenly ceased his gay, exploring little walks about the house, and would sit most of the day, sulking, in the refrigerator. Mrs. Popper had removed all the stranger objects, leaving only the marbles and checkers, so that Captain Cook now had a nice, orderly little rookery.

“He won’t play with us any more,” said Bill. “I tried to get some of my marbles from him, and he tried to bite me.”

“Naughty Captain Cook,” said Janie.

“Better leave him alone, children,” said Mrs. Popper. “He feels mopey, I guess.”

But it was soon clear that it was something worse than mopiness that ailed Captain Cook. All day he would sit with his little white-circled eyes staring out sadly from the refrigerator. His coat had lost its lovely, glossy look; his round little stomach grew flatter every day.

He would turn away now when Mrs. Popper would offer him some canned shrimps.

One evening she took his temperature. It was one hundred and four degrees.

“Well, Papa,” she said, “I think you had better call the veterinary doctor. I am afraid Captain Cook is really ill.”

But when the veterinary came, he only shook his head. He was a very good animal doctor, and though he had never taken care of a penguin before, he knew enough about birds to see at a glance that this one was seriously ill.

“I will leave you some pills. Give him one every hour. Then you can try feeding him on sherbet and wrapping him in ice packs. But I cannot give you any encouragement because I am afraid it is a hopeless case. This kind of bird was never made for this climate, you know. I can see that you have taken good care of him, but an Antarctic penguin can’t thrive in Stillwater.”

That night the Poppers sat up all night, taking turns changing the ice packs.

It was no use. In the morning Mrs. Popper took Captain Cook’s temperature again. It had gone up to one hundred and five.

Everyone was very sympathetic. The reporter on the Morning Chronicle stopped in to inquire about the penguin. The neighbors brought in all sorts of broths and jellies to try to tempt the little fellow. Even Mrs. Callahan, who had never had a very high opinion of Captain Cook, made a lovely frozen custard for him. Nothing did any good. Captain Cook was too far gone.

He slept all day now in a heavy stupor, and everyone was saying that the end was not far away.

All the Poppers had grown terribly fond of the funny, solemn little chap, and Mr. Popper’s heart was frozen with terror. It seemed to him that his life would be very empty if Captain Cook went away.

Surely someone would know what to do for a sick penguin. He wished that there were some way of asking advice of Admiral Drake, away down at the South Pole, but there was not time.

In his despair, Mr. Popper had an idea. A letter had brought him his pet. He sat down and wrote another letter.

It was addressed to Dr. Smith, the Curator of the great Aquarium in Mammoth City, the largest in the world. Surely if anyone anywhere had any idea what could cure a dying penguin, this man would.

Two days later there was an answer from the Curator. “Unfortunately,” he wrote, “it is not easy to cure a sick penguin. Perhaps you do not know that we too have, in our aquarium at Mammoth City, a penguin from the Antarctic. It is failing rapidly, in spite of everything we have done for it. I have wondered lately whether it is not suffering from loneliness. Perhaps that is what ails your Captain Cook. I am, therefore, shipping you, under separate cover, our penguin. You may keep her. There is just a chance that the birds may get on better together.”

And that is how Greta came to live at 432 Proudfoot Avenue.