|  |

#

July 1947, Rotten Row, Fishermans Bend, Melbourne.

The sky is low and sullen, the wind incessant. Sliding between factories and cargo cranes, a slow brown river churns as it meets the incoming tide. It laps and sucks at the rotten piles of a wharf where a few coal hulks, hulls red with rust and masts cut down to stumps, tug like tethered beasts at their moorings. Perched on a mossy hawser, a night heron stares into the murky water, feathers gleaming in the dusky light. The sky leaks darkness; shadows creep and pool.

The shadows gather deep about the largest of the hulks, moored downstream. Once a big square-rigger—iron hulled, strong built and elegant of line—decay now drapes her like a shroud. Her sides are rust-blistered and crusted with coal grime; slimy weed grows thick along her waterline and trails in the current like green hair.

Seeping through the dying city noises—a truck grinding its gears, a horse and cart clattering over cobblestones, the chug of a steam locomotive shunting wagons in the distant rail yards—comes a faint sound. It is surely just the wind soughing through rigging, whining and moaning amongst the wires.

But no . . . it sobs like a woman weeping . . . or perhaps she is laughing. Bitter laughter, rasping like rusty iron on iron.

The night heron takes to the air with a thud of wings and flaps away upstream.

An old sailor, trudging cityward, glances up at the beat of wings, trips on a bluestone kerb and curses. He’d been thinking of the sea, deep and dark, of mastheads sweeping a high blue sky, of trade winds, sunlight, and flying fish.

“But I hate the fucking sea.” Muttering under his breath, he pulls his coat tighter against the knifing wind. “And I hate Melbourne. May as well live in the fucking Antarctic.”

At some point in every voyage he had ever made, over a lifetime of voyages, he’d sworn that as soon as his feet touched solid earth, he’d run inland and never look back. And he’d sometimes done it—bought train tickets for towns as far from the sea as his money would take him, found work cutting down trees or digging ditches, but before he knew it, he’d be on a train again, heading to the nearest port.

Yesterday he’d shuffled up and down gangplanks in Victoria Dock. Today he’d done the same along Southbank. But there’s no work for a worn-out old coot when scores of young war heroes are keen for the few jobs going. Seems experience and knowhow mean bugger-all these days.

The sky is leaden, the air smells of coal dust and imminent rain. It’s an ugly part of town, south of the river, a scramble of factories and warehouses, concrete and corrugated iron, rust and rot. Newspapers and last year’s leaves scurry along bluestone gutters, driven by the interminable wind.

Out of breath, the sailor halts on a corner. He gulps in a wheezing lungful before doubling over to cough. Straightening up, he expectorates into the gutter and gropes in his seabag for his cigarettes, menthol as the doctor ordered. He takes a soothing drag, rubbing at the coal grit in his eyes and peers, blinking tears, at the river. A rusty tug labours past, trailing fumes and oil slick. Upstream the grey stucco walls and orange tiles of the Mission to Seafarers building are visible now between the warehouses on the riverbend. He’s almost there. Just a last trudge upriver, skirting the dry dock, to cross the Spencer Street bridge, backtrack downstream and there’ll be a firelit room, a comfortable chair, a hot cuppa and a biscuit, and a sympathetic smile from Deirdre, or Doris, or Dot, or any of the other ladies of the Harbour Lights Guild.

He’s just stubbed out his cigarette and got his weary legs moving again when someone passes from behind, knocking him sideways. The fellow doesn’t turn, but keeps striding along the street, a canvas seabag slung over one shoulder. The old seaman draws breath. He can’t see the fellow’s ugly mug, but he knows him. The tattoo of a bloodshot eye on the back of his shaved head is a dead giveaway. He knows that pit-bull noggin, hard as a cannon ball, the wiry frame, the bow-legged swagger. Most of all he knows those fists. The man punches like he’s swinging ingots of lead.

“Jack fuckin’ Driscoll,” curses the sailor. “Bastard’s going to the bloody Mission.” He looks towards the city, then back down the river, unsure where to go. He could jump on a tram back to last night’s cheap lodging house in St Kilda, but there were fleas in the greasy carpet and noisy drunks coming in at all hours of the night. One had thrown up in the old man’s shoes.

The first drops of rain sting his face and he pulls his coat collar up around his ears. Not too far downriver a coal hulk is moored on her own, one of the few still in use to service a dwindling number of steamships. Smoke rises from her galley chimney and the sailor fancies he can smell something cooking. The rain falls harder as he heads towards her gangplank. He’s surprised to see a tricycle and several battered bicycles leaning against the ship’s deckhouse, surprised too to see a woman taking washing off a line strung between the mainmast and the afterdeck. She glances at him as she hurries inside with her basket and a moment later a wiry little man comes out to block the top of the gangplank.

“You after somethin’, mate?” he asks, holding a newspaper over his head to keep the rain off.

“Just a place to lay me head tonight, that’s all; the deck’ll do as long as it’s out o’ the rain.”

“Sorry mate, not here. Got six kids aboard—two of ‘em down with the measles.”

The sailor casts an eye over the ship. Though she’s battered, rusty and coal-grimed, it’s clear she was once a pretty vessel. “Rona,” he says. “I crewed in this old girl years ago, just across the Tasman a few times. Nice ship—friendly, honest.”

“Still a good ship,” says the wiry man, taking one hand from the newspaper to pat the vessel’s bulwarks. “Not for long though. No work. Only steamer in port now is the dredge and once that’s pensioned off this old girl’ll be towed out and scuttled in the ships’ graveyard.”

“End of an era. Bloody waste.” The rain trickles down the back of the old man’s collar as he doubles over to cough. “They’ll be scuttling me out there soon enough,” he wheezes. “Need a fag.” He gropes around for his cigarettes.

“Here.” The wiry man comes halfway down the gangplank, holding out a light. “Look, if ya head downriver . . . ya know Rotten Row down on Fishermans Bend? Bit of a hike, but there’s a few hulks moored there ya can bunk down in. It’ll be dry and there’ll be coal for a fire.” He sidles back up the gangplank, frowning over his shoulder at the old man who hunches over, sodden and dripping, trying to keep his cigarette dry. “Wait here, mate; won’t be a sec’.”

A minute later he’s back with an oil lamp, a can of baked beans and a slab of fresh-baked bread wrapped in wax paper. “Present from the missus,” he says. “If ya could bring the lamp back tomorrow . . .”

It’s almost dark as the old sailor sets off downriver. To the west a dirty orange streak lingers along the horizon, silhouetting a row of factory chimneys that spew smoke into the inky sky. A ship churns its way upriver, portholes gleaming like yellow eyes. The wash from its passing sloshes and sighs against the wooden piles of the wharves. Along the deserted streets lamplight glitters on rain-wet paving.

He’s staggering by the time he gets to Fishermans Bend. His knee joints grind, bone on bone, with every painful step. But here at last are the hulks—four in a row, shackled like defeated leviathans to a couple of neglected jetties, their bows towards the land and sterns to the pull of the flowing tide.

The closest he recognises. The Shandon had been a fine ship in her day, but now—like all of them—she’s a truncated, coal-grimed ruin. Lamplight leaks out from her big deckhouse where, engulfed in a fug of cigarette smoke, several men sit round a table playing cards. The old man feels an odd yearning to join them, but even as he watches, their voices rise in drunken anger. He hitches his seabag from one shoulder to the other and shuffles on past into the darkness.

He stops when he sees her, a black shape looming against the black sky. She’s moored facing the sea and her imminent grave, and so deep in shadow that he can’t even see her gangplank.

Beneath the sheltering eaves of a locked-up warehouse, the old man manages to get his oil lamp lit. Rain flecks the air with gold as he holds the lamp aloft, and the vessel’s elegant counter-stern takes shape. Old paint and rust have long obscured her name, but he can just make out the first four raised letters: RANN . . . and, underneath, the name of her homeport: GLASGOW. He whistles softly. “Eh, you were a beauty once,” he breathes. “Still a queen under all that rust.”

Something niggles at his memory, touches him like a cold hand. He shakes his head, scattering rainwater, and stumbles forward. The barbed-wire barricade rigged across the gangplank does not stop him. He clambers ‘round it, cutting his hand and ripping the hem of his coat, then stands on the deck sucking the blood from his thumb and listening to the deep silence.

Such silence: it soaks up distant city noises like a sponge. He closes his eyes, ignoring the rainwater trickling down his collar; feels safe. The old hulk may be a wreck, but she’s still a ship and he understands ships, more intimately than all the streets and buildings and crowds and filth and bewildering bureaucracy of the land.

He climbs the stairs to the afterdeck. The timbers underfoot are rotting, and everything he touches is grimy with coal, but for now he’s captain of his own ship. He descends the narrow companionway into the aft accommodation. Tonight, he’ll sup in the captain’s saloon and sleep in the captain’s bed.

It’s not bad down below. The lighterman who last lived here had kept the place neat enough. The old man shines the lamp about the saloon, his eyes widening at the opulence of its etched glass skylight, its walnut and teak panelled walls, its cast-iron fireplace inset with glazed porcelain tiles—all shabby now, with coal dust embedded in every grain and groove.

There’s a bucket of coals beside the fireplace and even a wad of dry newspaper. He gets a fire going and heats the baked beans in the can; holds the scorched metal between folded newspaper to scoop up the beans with his pocket-knife spoon. The cheap beans and the bread taste like contentment. Rainwater drips through the leaking skylight to trickle down the slope of the floor, collects against the wall and runs through a door into the chartroom. The old man huddles as close as he can to the flames. He’s still wearing his coat and it steams in the heat. Feeling sated and happy, he lets his eyelids close.

He wakes with a jolt as his body topples sideways, flings out an arm and pushes himself upright. His heart beats in shock. He looks round in confusion before remembering where he is. Everything is as it was except that the saloon is much colder. “Fuckin’ icebox in here,” he mutters, throwing more coal on the fire.

The captain’s cabin is on the opposite side of the saloon to the chartroom—he’d checked it out when he first came down here and seen the horsehair mattress still on the bed. It’d be comfortable enough with his canvas seabag as pillow and his coat as a blanket.

The old sailor struggles to his feet. He glances towards the door to the captain’s room; sits down again. A dark shape beside the door makes his heart thud. The weak light from lamp and fire barely penetrates the gloom. He narrows his eyes, and the darkness thickens. It’s just me bloody coat, he thinks; I must ‘ave hung it up there.

The air is icy and a sharp, alien odour fills the saloon. It brings images—of a bleak place of drifting mists and drowning bogs.

I’m still wearing me bloody coat. Must be the lighterman’s coat left behind.

The darkness shifts, and grows far too big to be anyone’s coat. It keeps growing, and the peaty smell is swallowed by a tang of salt and iron and tar.

The odours trigger a memory, clear as sunlight. A wharf in Valparaíso, his own ship in for repairs after a storm. Another ship tied alongside her, a handsome full-rigger who’d lost her foretopmast in the same storm, and a stretcher—the body covered—being carried down the gangplank. Later, a seaman in a bar telling him: “Bloody ship’s a killer! Kills a man or two every voyage. It was ‘er captain this time, and that man loved his ship, more’n his wife and kids.” He tipped his beer down his throat and got up to leave. “Cursed, ya know. A death in the shipyard when she was built, and the mourning widow laid a curse on ‘er for all eternity.”

“Rannoch Moor,” quavers the old sailor. “That’s your name. From Glasgow.”

The darkness surrounds him, strokes his face, whispers inside his head. “My burning, bone-crushing birth . . .”

The clangour of a shipyard accident fills the old man’s skull, shouts of alarm, the roar of flames, the screams of the injured. He flinches back from the stink of flesh burnt to the bone. “Why pick on me?” His voice is high-pitched and hoarse. “I just needed to get out o’ the rain. What the fuck d’ya want?”

“What do you want?” The voice is a rasp, iron on iron.

“I want to go. Let me grab my things and I’ll be off.”

“You will stay.”

“Fuck you!” He scrambles to get up, but his limbs feel like water. “Damn! Bloody hell . . . you’re the ghost of that widow, the grieving widow that cursed!”

“Ghost?” Her mocking laugh defiles the air. “No, I am the curse. I am the curse of every widow, every mother, every woman whose husband, whose son, whose lover, went to sea and never returned.” Her form takes shape from the shadows like a nightmare.

“I am the curse,” she hisses, “of every fearful sailor clinging to a footrope above pounding seas. I am the terrified curse of the falling, the agonised curse of the crushed, the choking curse of the drowned.”

Her mouth is a gash in iron, rust-red; her eyes are rivets, rimed in salt and oozing. She stinks of bilgewater and blood.

“I am the pitiless cold, the endless hunger, the wound that never heals. I am the gulfing wave, the howling gale, the bloody eye of the cyclone. I am the salt-crusted, rust-blistered, iron-rivetted heart of the ship . . . and I can feel your ravening emptiness.”

“I’m not empty, I’ve just eaten a fuckin’ can of beans!” His voice shudders and shakes as he struggles for air.

“You crave more than food. You are empty. You have nothing. You are nothing.”

“No, no, no.” He closes his eyes, refusing to see her. “It’s you that’s nothing. You’re not real. But I am something. I’m a seaman, and I know ships. Whatever you are, you’re not a ship . . . You’re not the heart of Rannoch Moor. Ships are nothing like you.”

Eyes clenched shut, he pushes away from her blood-stinking breath and her rasping cackle, finds his back up against the saloon wall. “Shut up, hag,” he spits, “just shut it.” Clamping both hands over his ears, he tries to recite a poem he knows by heart, a device learnt years ago to stave off desperation. “These . . . these splendid ships, each with her grace, her . . . her glory . . .” He forgets lines, puts them in the wrong order, stumbles over words. “I touch my country’s mind, I come to grips with half her purpose, thinking of these ships . . .” He gulps air, goes on: “That nobleness and grandeur, all that beauty, born of a manly life and bitter duty . . . they are grander things than all the art of towns; their tests are tempests and the sea that drowns . . .” His voice is stronger now. “They mark our passage as a race of men—Earth will not see such ships as those again.”

Hunched over, ears clamped and eyes shut, he sits for a long moment. Slowly, he takes his hands from his ears. The saloon is silent but for a swishing sigh: water slipping and sliding along the ship’s hull. The deck tilts, and the sailor imagines the warmth of the sun and a clean salt breeze on his face. She’s gone, he thinks, she’s gone.

He opens his eyes. The filthy shadows have fled and firelight flickers on the walnut walls. The sailor feels its warmth on his left arm, his cheek. He turns towards it . . . and she is there, sitting beside him.

He jumps, flinging himself backwards into the wall as she turns her eyes towards him. But she is transformed.

She is a ship’s figurehead, carved by a master of the art and lifted to perfection by the finest painter. Alabaster skin, rosebud lips, cheeks blushing. There is a glint of gilt on her white, wave-kissed gown and one pale, long-fingered hand clutches a posy of moorland heather to her breast.

“See what you have done,” she sighs; “I have remembered how to be a ship again.” She smiles and the old sailor stares, his heart beating hard again, but for a different reason. His mouth gapes as she tosses the heather aside and rises. She is too tall for the saloon, and she shines like an angel.

“Let us go sailing, my captain,” she says, taking his hands and lifting him to his feet; “just you and me. We shall slip down the sullied river, cross the wide bay and fly from the fetters of land.” She smells of sunshine and her voice is a zephyr. “We’ll snare the quartering winds and cross the seas and oceans of the world. Come! We must catch the tide! Go now, cast off the mooring lines!”

“Yes, yes,” he gasps, entranced, before old habit takes over; “Aye, cast off the mooring lines!” Dragging his eyes from her, he makes for the companionway.

Up the stairs to the deck he goes without a backwards glance. He’s failed to notice that her skin is beginning to craze. The cankered paint cracks and flakes away, the decaying timber beneath bulging through the gaps like black fungus. The sailor doesn’t smell the rot and putrefaction, doesn’t hear the rasping laughter begin anew.

Like a man half his age, he runs along the deck to each of the bitts, slackening the springs, the breast lines, the bow and stern lines. A small voice in his head remonstrates with him: What the fuck are you doing? Are you mad? You’re not going anywhere with cut-down masts and no sails . . . one man can’t sail a ship this size anyway . . . and there’s no bloody food or water aboard. But he ignores it, for its surely lying.

He bounds down the gangplank, swings himself round the barbed wire, and dashes forrard to cast the eyes off the bollards. The mooring lines are weighty, as thick as his forearm, but he knows what he’s doing; he’s done this hundreds of times. But never on your own, argues the small voice, and always under orders.

He’s released all the lines but the aft spring when the ship, nudged by the current, pivots her bow—out into the river. Her stern swings into the wharf, and the spring snaps taut, tripping him up and throwing him off his feet. He falls, flailing, into the narrowing gap between the ship and the wharf, grabs at the bollard, and for one hideous moment feels the weight of the ship crushing the life out of him. But somehow he hauls himself up again. The line released, he chases the gangplank as it drags across the wharf timbers, leaps for it and is back on deck as it falls away into the river. The ship is free and moving fast, her bow towards the sea.

He stands at her helm, the varnished wood smooth beneath his calloused hands. She answers him, so quickly, so kindly. A steady wind sings high in her rigging, her great sails belly and crack as she heels to the breeze and bounds down the bay. The sun rises on her port side, sending shafts of gold into the towering clouds. Gleaming dolphins leap beneath her bowsprit and wide-winged seabirds wheel above her mastheads. The old man looks aft, where the foam-white wake curls behind the ship across an infinity of ocean and knows he need never again touch land. She is all he needs now. She is everything.

***

Two days later, the morning newspaper, The Argus, prints a quarter column article on page five. The heading reads: “Killer ship claims last victim.”

“The body of able-seaman, Mr William Laney, 67, was discovered on Tuesday morning. He had fallen from a wharf at Fishermans Bend on the Yarra River, and been crushed between the wharf timbers and the iron hull of the coal hulk, Rannoch Moor. It appeared that he had been attempting to cast the hulk adrift. Mr Laney was not married and has no surviving family. His friend, Mr Jack Driscoll, boatswain, described him as ‘a skilled rigger, a loner and a dreamer, and a man who lived for ships and the sea’.

“In a sinister twist to Mr Laney’s tragic story, it is known that the Rannoch Moor, originally a full-rigged ship built in Glasgow in 1883 for the South American nitrate trade, had an unfortunate reputation as a ‘crew-killer’. During her twenty-two years at sea, at least nineteen of her crew are known to have drowned or died accidentally, including one of her captains. In recent years, since her conversion to a coal hulk, lightermen living and working aboard have described the vessel as ‘haunted’. The Rannoch Moor is scheduled to be scuttled this Friday in the ships’ graveyard between Point Lonsdale and Barwon Heads. It might be wise for the tugboat crews, and all of the men working to achieve the sinking, to ‘proceed with great caution’!”

––––––––

November 2020, Ships’ Graveyard, four nautical miles east of Torquay.

A small wooden boat bounces at anchor atop the outgoing tide. Inside the tiny wheelhouse a man in a captain’s hat fiddles with the radio, while on deck two divers, empty tanks discarded and wetsuits running with saltwater, stare over the side into the darkening waves.

“He’s gonna be out of oxygen,” says one of the divers, glancing at her watch.

“I told him there’d be too much gunk from the Barwon today,” says the other, his voice shaking. “Followed him to that wreck but lost him. It’s like bloody soup down there; couldn’t see my own hand.”

“You got through to Search and Rescue yet?” The woman turns frantically towards the wheelhouse, but the only reply she gets is a string of expletives and the sound of something being thumped. “Fuck,” she says. She reaches for her phone again, but it’s just as much out of range as it was the last time she checked.

“What about flares? Could we send up an emergency flare?”

The two divers look towards the man in the hat, but he shakes his head ashamedly. “Forgot to bring ‘em,” he mutters.

They fall silent, the woman scanning the darkening horizon for other vessels. But there’s nothing—just the heavy twilight, the slap of waves against the hull, and their own distressed breathing.

“Shit! Did you hear that?”

“Hear what?”

“Laughter! I heard laughter!”

“Out here? You’re nuts. Just a seagull squawking.”

But then they all hear it. They stare at each other through the gathering darkness, eyes wide, hearts thumping.

“Fuck,” she squeaks. “Get the anchor up. We gotta go.”

The sun finds a gap in the clouds and shoots a blood-red ray of light across the sea. When it sinks moments later it sucks down with it every last scrap of luminescence.

They’d flooded the engine and flattened the battery trying to get the boat underway, and now they huddle together, shaking with cold, as their vessel drifts alone upon the deep. The sky is starless and moonless, the wind has died. Night presses in, as black and silent as a tomb.

Mute with dread the three stare, wide-eyed, blind, into the void. They make no sound but for their shuddering breaths, their drumming hearts.

Then they hear it again, a laugh that scrapes through the dark like iron on rusty iron.

About the Author:

E.H. Alger grew up in the suburbs of Melbourne. After graduating in art and design she became a freelance book illustrator, working for many of the major publishing houses. She also wrote and illustrated an acclaimed children’s picture book, ‘Bertie at the Horse Show’, published by Penguin.

Her 2018 fantasy, ‘Winterhued’, was her first novel and she is presently working on a fantasy trilogy.

She’s travelled widely, voyaging the world’s oceans aboard eight sailing ships, and for many years was a volunteer aboard Melbourne’s tall ship, ‘Polly Woodside’ (formerly the coal barge, ‘Rona’, that makes an appearance in her story).

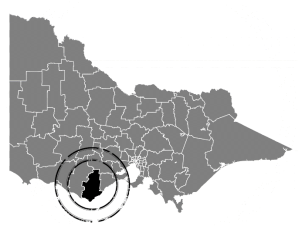

She now lives far from the sea in rural Victoria, near the border of Bunurong-Gunaikurnai country, surrounded with rescued animals including several horses and a pet Brahman bull.

Victoria’s Otway Ranges can be as treacherous as they are beautiful, containing both wonders and impenetrable mysteries.