|  |

#

Djeran (autumn): the season of adulthood. Cooler weather begins.

There’s a toddler floating in the air by your head. Your mouth twitches and you give a tiny wave, then push the soft arms away, towards her mother.

“Incoming,” you say.

The woman—you don’t remember her name, only that she’s a Flyer, too—looks up from her phone in time to catch her child. You try not to judge, but this is a Parent’s Group. Everyone judges everyone here, from the too-good-to-be-true, two-dad couple to the nanna who reminiscences on ‘better times’. Even the group’s host has a plastic smile, moulded to fit each week’s critics and crises. You turn away before anyone can see the accusation in your face.

Isla is sitting on the mat playing with the shape sorter. She selects a chunky star and with intense concentration tries to push it through a square hole. You let her experiment, give an encouraging hum. She doesn’t look at you, but her frustration pulses in scarlet bursts through your Mother-Daughter connection, the invisible line that links your minds as indelibly as your womb’s umbilical once linked your bodies. Your unique, paired ‘quirk’. You send back a pulse of love and reassurance. Golden, like the light on the morning her father left you—a colour he neither gave nor received.

But Isla will never lack for love; you promise her that every day.

“When do you think she’ll talk?” Kristen leans in from the right. Her boy, Sean, has the most beautiful blond hair. He’s sitting on her lap in her wheelchair, and she’s braiding with her expert, Patterner fingers. Twist, fold, twist.

You shrug, hiding tension with the movement. Why do people have to keep asking? “When she feels like she needs to, I expect.”

“That’s right. Her quirk’s Telepathy, like yours, Nessie?”

I nod—close enough—noticing Kristen’s pink, manicured nails. How does she get the time?

“Amir’s quirk is Mathematics. He doesn’t show it yet, but it will come.”

The comment comes from Farya. You both turn to her with soothing noises. She says it every week. Of course, she doesn’t have to worry about secondary quirks manifesting in Amir, since both she and her partner have Maths as primary. She just needs patience. Meanwhile, Amir sits on the floor sucking his fingers, not caring a whit about his future.

“Must be nice.” Kristen sighs. “I was up all night trying to figure out what Sean wanted. His screams broke the mirror in the hall. And now we can’t find the cat, either.”

“Cat hearing is extra sensitive,” Farya says. “I’d be surprised if she came back at all.”

You glare, pushing back the urge to Transmit your thoughts on that answer, then turn to Kristen. Her perfect eyebrows are frowning at Farya, with hollows darkened by lack of sleep and sympathy. “Don’t worry about it,” you say. “The cat will come back. Have you tried the neighbours?”

She nods. Sighs. “Oh, yeah. That’s a good idea.”

You twitch your lips again. Your phone vibrates and you grab for it, saved by the alarm you set this morning. A tip you picked up from a website.

“Oh, look at the time. I have to leave early today,” you say. Then, “Isla.”

Your daughter looks up. Her thoughts are purple and black, confusion with a swirl of rising anger. The star is still in her hand. You crouch by her side and help her push the shape into the correct place, prompting a laugh. The sound is a tingle of joy, and bright yellow overtakes the darkness. You smile. “Come on.”

She smiles back at you; at the words you sent telepathically, understanding at a level beyond language. You wrap her in your arms, this bundle of child with her wild, curly, dark hair, and you think about how much the others are missing.

Kristen and Farya share a glance. “See you next week, Nessie,” they call. “Bye, Isla.”

“See you,” you say, hand waving because that’s what other people do to say goodbye. Baby hands copy the gesture.

Isla nestles into your chest in her carrier. She’s getting heavy but you’re not ready to give up this last physical reminder of her babyhood. You leave with a final glance at the room. Just an ordinary hall in the back of a church, plastic chairs and patterned rug laid out in the centre, half a dozen children and their carers playing in the cool April morning. You think of them as your friends, sort of—but a friend is someone who brings coffee when you’re feeling sick; a friend is someone you can greet at the door in pyjamas and bed hair and tear-streaked mascara, and you know they won’t judge because they’ve done the same. A friend is irreplaceable, and your friends were left behind when you moved here. Away from him.

You shake your head and nuzzle Isla’s. It smells of coconut shampoo and the distinctive scent of baby: milk, body oils, washing powder. Innocence. Love. Your heart warms and Isla’s connection brightens to orange, mingling with your gold.

The morning sun is nearing midday but the wind is brisk. You walk into it to the foreshore, taking your time. Aware of the body attached to yours, of the heart beating next to your own and the tiny toes in their pink socks and sparkling shoes swinging at your hips. The sky is the pale blue of Djeran season, the Noongar name for autumn, and you think about the gloves you’ve been knitting—poorly—wishing you’d finished them already.

As you pass the boutique baby shop a dress catches your eye and you almost go in, but it’s not a good idea. Centrelink isn’t due until next week and you’ll regret spending, you know you will. The store assistant in the window is arranging a mannequin and her eyes first light up at the two of you, then move on with barely a flicker. She knows you won’t come in, somehow. They always know. You wonder if there’s a school for shop assistants. Do they teach how to Read customers? To use quirks for more efficient and lucrative sales?

Could they teach you to tune in to others better?

Isla’s link gains a thread of purple and grey. Worries. Guilt strikes your chest, a deep and familiar pang. Sometimes you Transmit more than you should, more than you realise. You take a deep breath and focus on dispersing your thoughts.

The footbridge here is white and steep, but the canal beneath is deep green and slow. You watch the water flowing, let your thoughts drift along its current, try to see your emotions without feeling them, without tangling Isla in them, too. They are leaves on the stream. Floating on the water they lose their potency; disappear beneath the bridge. You let them go. Loss. Sadness. Anxiety for the future. Concern for your daughter, wondering when she’ll speak, when she’ll start asking about her father. The inevitable anger at him that hasn’t faded with time, despite what everyone said. A deep, leaden fear that no one will ever want you again.

Loneliness.

You hold Isla tight and wonder how you can feel this way with your heart’s companion in your arms. She falls asleep while the clouds meander and the sun reaches noon, while you watch the water and wish someone could hear you. The greatest irony of being a Transmitter: no one actually wants to know your mind.

***

Makuru (winter): the season of fertility. Wettest, coldest, and windiest time of year.

You sit beside the river, making the most of a day without rain. Recreational boats pass by; pelicans sail on the estuary like miniature yachts; buoys flash their red and green lights out on the water. Isla is on the grass behind you, chasing seagulls and throwing scraps of bread. Her giggle is a pulse of golden joy that lets you know where she is without having to follow with your eyes. Which is a good thing, because a dolphin has swum up to the quay and is launching themselves out of the water. A white man takes shape mid-leap, water streaming from him. He lands gracefully, bare feet on stained wood.

You stare—and why not? He’s in good shape and it’s been a long time since you’ve seen a naked butt that wasn’t Isla’s. His scalp is bald, his eyes the grey-blue of shallows in a storm. He catches you watching him, removes a plastic pouch from around his neck where it hangs on a blue string, and shakes out a micro-towel. It barely covers anything, and it’s the middle of winter. He grins. You blush.

It’s been a long time since a man grinned at you, too.

You turn away. Isla’s shrieks at the gulls echo telepathically, and that means she’s broadcasting—the piercing cry is reaching more than just the birds. People are staring, wincing, covering their ears.

You run to her. “Hush, baby.”

A police officer Blinks in. “Is this your child?”

“Hush. The birds are gone. You scared them.” You hold her tight. She scared everyone, but now her own fear has risen. Orange, gold, and blue—threads to soothe. “Calm, now.”

There’s a reason nobody likes Transmitters. Who wants someone else’s thoughts projected into their head? Only the advertisers and security companies want to hire you, but being a walking billboard or alarm system isn’t glamourous, either. You hug Isla and wish the world would give her a chance.

“Move along now, Miss.” The officer is a short woman with crisp lines in her uniform and bird crap on one shoulder. Her eyes are small and beady.

Like a crow, you think, and she frowns before you clamp down on your thoughts all the harder. Don’t let them hear. The tightness in your chest is moving to your head, turning scarlet.

“We were just leaving, anyway,” you say, and scoop Isla up.

But you’re not going to be scared away by anyone, superior quirks or not, so you take your time putting her into the carrier. Clip the clips, and leave without a backward glance. Your departure would have been more satisfying if the police officer had stayed to witness it, but only seagulls remained. Once the screaming stopped, no one paid attention to the two of you. There were other shenanigans to be had at the playground. Even the dolphin man had disappeared.

Well, sod them all.

***

Birak (first summer): the season of the young. Dry and hot, with cool sea breezes in the afternoon. Time for fire.

Your mood is dark as you wander into a café, despite the bright sunshine. It’s the fog you often feel after another Parent’s Group meeting, another opportunity for other people to show off their children and their quirks. You tell yourself you’re still going for Isla’s sake, and hide negative self-talk under false smiles and silent bitterness. But Isla’s skill today was crying so much you had to put up a shield to dampen the volume. You couldn’t wait to escape.

The café is decorated in dark greens and golds, its polished wood tables scattered with chain brand menus. Isla is asleep on your chest, curls sweaty on her forehead. You really ought to buy a pram. At two, she shouldn’t be carried around anymore. But who cares about ‘should’ anyway? Your mother’s last ‘should’ was shouted at you the last time you spoke. And even though she was right—goddamn, she was right about him—you still can’t tell her that to her face. Maybe on the phone. One of these days.

You push the thought away like a cloud and consider the girl behind the counter. Her thick black eyeliner reminds you of teenagehood and freedom. “Skinny latte,” you order. Then with a glance at the specials list, “A shot of green as well?”

She winks. So does her tattoo, a jolly fuchsia pig on her arm. “Sure.”

Green is for Luck, and it could be good or could be bad, but you’re feeling young and reckless all of a sudden and asking yourself, why not? You’ve got the extra three dollars from your new job selling tickets for the local pirate cruise, so why shouldn’t you give your life a little shake-up? Monotony belongs to the dead.

You step aside to wait while the next customer orders. You give him a second look, then a third. It’s the dolphin guy. The one from that day after Parent’s Group back in winter. The one you’ve been unashamedly looking out for on your walks along the Esplanade these past six months. But while you’ve seen plenty of dolphins, none turned into him.

He orders an espresso, topped up, in a tiny keep cup featuring an Aboriginal design. You aren’t surprised at the eco-friendly choice. It makes you smile. Isla gurgles in her sleep. You look down at her, and when the barista calls your name, you are startled to find that dolphin guy is standing beside you.

He cocks his head as you collect your coffee. “Nessie?”

“Um. Yes?” The paper cup is warm in your hand; you grab it with your other as well, as if the warmth will seep through your veins and kickstart your brain. He is wearing board shorts and a white shirt. Sunglasses balance on the back of his neck. He is completely normal and completely extraordinary at the same time. Your heart races.

“Nice name,” he says. Does he remember you?

“Barry,” the barista calls.

He reaches past you for the takeaway.

“Same to you,” you say. Though you don’t mean it. Barry?

“You don’t mean it,” he says. His smile is self-deprecating. “But that’s okay.” He shrugs. “See you around.”

Crap, he heard you. You look at your cup. Is the Luck worth it?

With exaggerated care you place it back on the counter, then follow him out. “Sorry,” you say.

He turns; outside, the sun bounces off the water into your eyes. You shade them with one hand while the other shields Isla’s sleeping face.

“I didn’t mean to be rude,” you say. “I’m actually Anessa, and this is Isla. I’m a Transmitter.”

“I got that,” he says. Sips his espresso. We look at each other.

“I just meant . . . I don’t know.”

He raises an eyebrow.

Sod it. “I didn’t think of Barry as a dolphin name.” Heat rises in your cheeks. That’s it, he’ll go now. You made a fool of yourself. Making fun of people’s names is not going to make you friends. Idiot.

But he laughs. “What should I be called? Flipper?”

“No.” Now your entire head is on fire. Transmitting instead of speaking? Your embarrassment surges, thick and scarlet. Isla stirs.

“It’s okay.” He finishes his drink and tucks the empty cup into his satchel. It’s a plain khaki shoulder bag, at odds with the surfer look, yet it works for him. He grins at you. “You’re right, of course. My nickname is Barry; my real name’s Marron. But that’s too oceany to fit in around here, you know. Barry’s more ‘average Aussie.’”

You manage to nod your head. “Oh.” And here you are with your Loch Ness Monster nickname.

He frowns, a small dip of his eyebrows. “You broadcast a lot.”

“Oh.” You wince and tighten your inner walls. “Sorry.” Must have been the strain of holding back at Parent’s Group. Normally, you feed the bond with Isla so your quirk doesn’t become stifled, but that’s all. You can’t bear other peoples’ faces when you Transmit. The expressions like his.

“It’s okay,” Barry says. He smiles.

You smile.

You realise you’re standing goofily on the sidewalk, blocking the way for pedestrians. You step onto the grass. He turns to go, but, “Do you live in Mandurah?” you say, and he stops. Two steps and you’ve caught up. “I mean, I think I saw you before . . .”

“You did see me before.” His glance is amused. He walks along the Esplanade path, a steady pace so you can keep up with your toddler-in-arms. “I’m a transient,” he adds, though you don’t know what that means.

He looks at you as if he heard your thought. Are some quirks more receptive to Transmission than others? It’s not something your mother talked about; not that anyone else would volunteer information, either. Each quirk’s ‘quirks’ are kept a secret, only for those in the know.

“Transient is a scientific term for dolphins—and whales—who travel between locations,” Barry says. “There are inshore, river, offshore, resident, migratory, and transient types. I spend time in different places along the coast.” His mouth curves in an inviting smile, and your racing pulse returns. “We’re hard to pin down. We’re quite Empathic as well.”

You fiddle with Isla’s straps.

He pauses, proving his point with a look. “I pick up on thoughts, feelings, and emotions, whereas you project them.” His blue-grey eyes alight on Isla. “Your little one does both, I see.”

You laugh in surprise. “What?”

Isla’s eyes have opened, their clear brown irises focusing on Barry. She is a rainbow of emotion, with the bright green of excitement the strongest. She kicks her legs and sends you a picture of herself running.

“We’re going home soon, baby,” you tell her back, but her forehead creases and she laces her thoughts with dark brown.

“No. Run.”

“Isla,” you tut aloud. She kicks again.

“Mummy talk. Isla run.”

“You’ve got an Aqua quirk in your family, don’t you? Let her down if you like,” Barry says, and Isla smiles at him.

You frown at the two of them, but you’re too intrigued to say no. “Conspirators.”

Undoing her carrier, you let Isla out. She grabs Barry’s tanned leg in a fierce hug, then heads off to chase pigeons. You chuckle, pleased that Isla touched someone other than yourself.

Barry laughs too. The sound rings like bronze bells in your ears.

An early afternoon breeze stirs the air, laden with the scent of salt and seaweed from the estuary mouth. You glance at Barry. What does he mean about Aqua? The only watery thing about you is the Nessie nickname your father gave you, the last thing left of him.

Barry gestures to the low esplanade wall. You sit because he asked; he settles beside you. Tanned, gorgeous, interesting. Facing away from the water.

Your head is spinning; you stare at the grass; the birds; the toddler. “Are you going to be around for a while?”

“I don’t know yet,” he replies.

You try not to let disappointment escape its containment field. But when you gather courage enough to look at him, his eyes meet yours with a hint of contemplation that warms you more than the sun.

***

Bunuru (second summer): season of ripening. Hottest part of the year. Time for coastal living.

You’re forced to call it ‘casual dating’ when cornered by Kristen at the play centre. It’s the end of summer and the heat has you tossing back Panadol every day.

“So, what’s he do?” She prods and pries.

An image of the dolphin man Transforming heats your cheeks a little. “Barry? He’s a . . . fisheries observer,” you reply, distracting yourself by watching Isla jump about the ball pit, semi-pleased with your evasive—and quite true—answer.

“Oh, really? Does he have a boat?”

“No, I don’t think so. Isla!” You pivot. “Tell him to stop if you don’t want more balls Teleported at your face.”

“I suppose he has one at work, then.”

The other child, a bully in the making, shrieks, hands over his ears.

“Not like that!” “Sorry, just a sec.” You wave Kristen off and almost trip over in your hurry to Isla. She grins, unrepentant, and for a moment you wish you could praise her. Instead, you put on your Mum Face and frown. “No death threats in the playground, Isla.” You’re loud enough another parent blanches and pulls their child away. That’ll teach them not to throw things.

Sighing, you remind yourself to stop thinking like that. Remember the parenting class. “If you want someone to stop, say ‘Stop it, I don’t like it’ and hold up your hand like this.” You show her, palm facing away from your body.

“Stop, don’t like it,” she says in your head, with a sign as big as a roadworker’s. Your amusement trickles through in hints of yellow-green and she beams, so you have to take her away from the ball pit before anyone else sees your disciplinary failure.

Kristen is still fixated on my non-love-life. “Does he go bowling? Maybe we should do a double-date sometime.”

You don’t think so. Sean, her mane-haired boy, drove his father away with his banshee routine before he turned one-year-old. You have a suspicion he’s a factor in Kristen’s string of bad dates, too. Not that she’s the only mum whose child’s quirk doomed their parents’ relationship. Your own ability has sent every man packing. Well, until Barry. Though you’re not quite sure where you stand, there. Or swim.

You smile, collect Isla’s puppy-decorated bag, and offer cold chips to Sean to finish off. “I don’t know,” you say. Kristen’s expression is blank and quiet. “He’s good at surfing though”—probably; the dolphin skills are likely to transfer to human, you think—“so maybe that could be something.”

It doesn’t mean anything and you’re already regretting the comment, but Kristen’s mouth curves tightly nonetheless. She traces Patterns in spilled table salt. “You know, sometimes I think you don’t like me very much, Nessie.”

“What? Of course I do!” Where did that come from? You shake your head, partly to dislodge the unquiet thought that maybe she heard you. No, you’re more careful these days. And anyway, it’s not true.

You grab Isla’s hand and her backpack, but hesitate before leaving, to try to turn things around. “I didn’t mean . . . There’s adaptive surfing for wheelchair users, isn’t there?” Your chest is tight. “Anyway, single mums need to stick together.”

You force a smile. No one else knows about the loneliness. No else seems to care. It was a year ago now, and she’s the only one from Parent’s Group you can still stand to see. The competition wore you down.

“Yeah.” Kristen sounds unsure.

Isla is sending images of donuts and lamingtons into your brain; she’s tugging at your hand. “Stop that,” you send.

You should stay, make her feel better. Kristen’s been on the low since her cat was found dead at the side of the road. But you’re running out of words—or thoughts—of comfort. And it’s not like anyone’s ever given you any to show how it’s done.

Isla’s transitioned to Pop Tops and cheesies now. “Next week, same time?” you ask, already moving away, hustled by your child.

“Yeah, alright, Nessie,” Kristen says. Waves.

It’s weeks before you realise neither one of you has texted.

***

Djeran, again. Season of adulthood. Of change.

You’re in a slump. Isla is teething, which keeps you up all night. Your girlfriends are too busy to go out, suspiciously so. It’s after Easter and the father of your child is behind on his support payments like he is every damn year at this time. Work is slow. The dishwasher just broke. It’s only Tuesday.

When Barry rocks up at six p.m., you almost cry. He brings red wine and salmon, and nuggets for Isla. She shows him her sore tooth; he says the right things and laughs at her telepathic jokes that you can’t hear; he sings her old lullabies.

When she’s asleep at last, you relax together on the couch with the TV on to cover the sound of kissing.

“What made you come over tonight?” you ask, when lips are swollen and in need of moisture. The wine is half gone. Barry doesn’t drink.

He reaches out and strokes your hair. It’s not styled today, but he admires it like the brown tresses belong to some fancy actress. He kisses it. “You didn’t like dinner?”

“That’s not what I—” You pause at the tease in his eyes. “I did. I liked it a lot.” This is what he does, now. He comes and goes, with the tide, with the moon. Sometimes it’s for weeks, sometimes mere hours. He rarely texts. No Tech wizard has been able to modify or waterproof a phone for a marine mammal’s use.

There’s a question in his eyes, but you clamp down your walls. He doesn’t want to hear your woes. “Let’s see if we can find something you like,” you whisper. Knowing what you’re doing, neither minding. You lead each other to the bedroom.

You take it slow. Let him see your bitten nails, your undyed hair, your caesarean scar. He shows you the nub on his back that turns into a dorsal fin. You both laugh.

Love and the quiet night swallow time.

Afterward, he answers your question. “I felt you out there, Nessie.”

“Hmm?” You are laying in the crook of his arm, tracing waves on his bare chest.

“You’ve made a connection. Here.” He places your hand over his heart. “I knew you were sad today. Angry. So I came in.”

You sit up. “But—”

“Your control is less than you think it is, baby. And I am an Empath, too.”

You frown. Your cheeks heat, your fingers grow chilled. Tears form in the corner of your eyes.

“It’s not a bad thing,” he says, capturing your hands in his.

“But that’s so far,” you whisper.

He smiles. “We both have water in our veins. And you’ve always been a broadcaster.”

“No. I don’t know what you mean about water, but I don’t Transmit as much anymore,” you protest. “I used to. But not now.” Not since Isla’s father walked away. He’d said he couldn’t stand listening to you for one more second. You’ve worked so hard to smother your voice since then.

“I’m sorry, Nessie,” Barry says. He leans up to kiss you, but you pull away. There is hurt in the pool of his eyes.

The room is too cold now, the night too dark. You jump out of bed, turn on the light and reach for a robe.

“You’ve been able to hear me . . . since we met?” you ask. Oh God, all the little things that have crossed your mind, the tiny spites. The things you thought you’d kept to yourself. He nods, and another chill streaks along your spine. “Have other people, too?” Your panic rises. You can’t stop shaking. One glance at his face and you can see the truth.

He gets up. Tries to hold you. “Shh, Nessie, it’s alright,” Barry says, but your ears are ringing and the words slide straight through. “From what I’ve learned about Transmitters—and yes, I’ve done some research, and no, it’s not out of concern—from what I’ve learned, bonds across distance are rare. Maybe it’s the Aqua link, magnifying your quirk, maybe something else. And yes, you’re a broadcaster, but Nessie, look at me”—he tilts your head—“Baby. You make sales at the kiosk because you love your job and people can feel that. Your friends know what you’re thinking and continue to be your friends because they like you. Your bond with your daughter is so bright I can almost see it.”

His hands squeeze gently. “You love and are loved, Nessie.”

You shake your head. The salt tears are flowing and it’s appropriate, really, that you end up drowning because of him. You think you understand now, why everyone leaves in the end. You never knew.

No one ever said.

The peculiar looks, the falling away of conversation . . . You’ve been kidding yourself for so long that you’d made it better. No one except him ever said a word—and those he did were never kind, nor free from manipulation. Which prompts another thought: Isla. The one person to whom you’ve always Transmitted on purpose, whose bond with you is so strong . . .

Your tears turn to wracking sobs. “My baby,” you cry, and Barry tells you to hush or she’ll wake, and you cry more.

“Mummy?” Your tiny human stands in the doorway, fluffy unicorn in one hand, rubbing her eyes with the other. Barry hides his nakedness while you run to her, fall on your knees and pull her in tight.

“I’m sorry, I’m sorry,” you whisper, over and over.

Isla’s heard your every thought for two and a half years, her entire life. Every uncensored criticism, every nasty comment, every internal debate. Fury; sorrow; self-hate and spiralling depression. She’s probably heard your inappropriate thoughts about a certain dolphin man. Did she hear you the times you wished she’d never been born? When you wished that you hadn’t?

People are awful, in the deep places inside themselves. No child should be exposed to this side of humanity. You cry for her innocence and your mistake, your blind belief that everything would be okay if you only kept it in. You cry because you’ve been feeling sorry for yourself for so long that you forgot to consider how she felt. You took her bond for granted.

The bond between you is grey and purple and twisted like a hurricane.

Isla squirms away and runs to Barry, who’s clothed and silent now in your maelstrom of emotion. “She says, ‘Stop it, I don’t like it,’” he tells you quietly.

You take a breath, a deep one, but you’re suffocating under an ocean of drowning waves. If you close your eyes, can you forget it all? You’re an awful mother. A terrible person.

“No, Nessie. You’re not a bad mother. You’re just you, and you’ve been doing the best you can.” Words. Just words. “She’s an Empath, Nessie. She’d have heard it anyway.”

Oh, God. You didn’t believe it when Barry first told you, but Isla’s father’s quirk wasn’t Empathy, so how could hers be? It had to be his secondary. And if so . . . Chalk it up to another thing the bastard hid from you.

Oh, God. Isla never stood a chance.

Fear returns, a tidal wave.

But they are there: the dolphin man and the rainbow child. One holds you up, brings you to the surface. One lights the way with her love the colour of the rising sun.

Morning comes.

The tears dry up. Cold is replaced with the warmth of four arms.

You breathe. It’s only the first step in the long swim back to shore. But you are still alive.

You can still fix things.

You can still change.

The alarm sounds, a gentle song to wake the day, and Isla asks for breakfast, hoping for strawberries. Promising all the strawberries she can eat, you hold them close, these people bonded to you. Your daughter, who had no choice, and your lover, who did.

***

Djilba (first spring): the season of conception. Wet days and clear, cold nights mixed with pleasant, warm days. Wildflowers grow.

You were wrong, of course. Isla has a choice. Same as how you chose to break away from your mother, and she from you, the choice remains to you both to reverse that decision. And despite your unique Mother-Daughter link with Isla, despite the love between you—or because of it—your daughter will always be able to walk away if she wants to. Her telepathic quirks are both gift and curse, but so are all powers. One just has to learn how to use them.

That’s the difference between you: a mother who never learned to control her emotion, and a daughter who will be taught everything she needs. Because she deserves it.

But so do you.

You walked past the baby boutique store again yesterday, when Isla was at daycare. She’s been going twice a week, enough for you both to practise some distance, some independence. The shop assistant eyed you as you entered. Were you there for a friend, or yourself? For fripperies or expensive clothes or beautiful children’s books? Her eyebrows rose when you told her what you wanted. She gave you the number of her old teacher.

You start classes next week on ‘How to recognise other peoples’ needs’.

It was your father’s side that had the Aqua quirk, buried and half-forgotten. And of course, your mother never said. Your doctor had looked at you like a crazy person, thirty-two and asking what your secondary quirk might be, but they’d prescribed the test. Results were clear, as was the advice: stay away from large water sources, unless you want your primary quirk amplified. Ironic, considering where you live. “Thank you,” you’d Transmitted—to the nurse’s distaste—and walked away.

Barry gave you some contacts who might shed more light on this new quirk, and you think you might talk to them. In time.

He left three months ago, hunting offshore for the season. Your dolphin man said he’d come back, but you won’t blame him if he doesn’t. You’ve come to understand that it’s okay either way. He helped you see yourself, and late as it was, difficult as it was, that was the most important gift you’ve ever received. If Barry returns, you’ve vowed to take him bowling. To cook fresh crab from the market, spend a week away with Isla in Margaret River. Watch the ocean and the sunset and just be happy.

And if he doesn’t come back? You’ll do it anyway.

You bury your face in your scarf. It’s rainbow-coloured and made of the softest yarn, almost too warm to wear. Infused with Isla’s scent; a simple charm. It’s your first successful knitting project. The plan is to make a blue one next, with a gentle wave lapping the edges in green. A matching beanie for Isla for next winter.

Today, your daughter holds your hand as you stroll together along the esplanade. A pelican lands nearby, graceful in the water yet so huge. Its yellow eyes watch you. You wave. Isla hops onto the wall, balancing with exaggerated care as you walk together. Another child floats past in the air, turns a cartwheel over the river, and giggles. Isla laughs too, and you turn to see someone you vaguely recognise hurrying your way.

But no, it’s not that woman from Parent’s Group last year. She grabs her child, and with a leap she is airborne too, and they are Flying towards a group of friends sitting beneath the foreshore trees. Moreton Bay figs. Imported from the East Coast. Out of place, yet now they belong. You watch, and you hope that someday you can be part of something like that again.

“Mummy, cuddle?”

You turn. Isla has come back and waits with arms outstretched. Golden orange love fills the air between you, sparkling with the winter sun and the joy you have for each other.

Her first words spoken aloud. They aren’t a request to receive, but to give.

About the Author:

Emma Louise Gill is a British-Australian speculative fiction writer and coffee addict, living on Gnaala Karla Booja. Her short stories appear in AntipodeanSF, Crow & Cross Keys, Curiouser Magazine, Etherea Magazine, and others.

She blogs at emmalouisegill.com and procrastinates on Twitter @emmagillwriter.

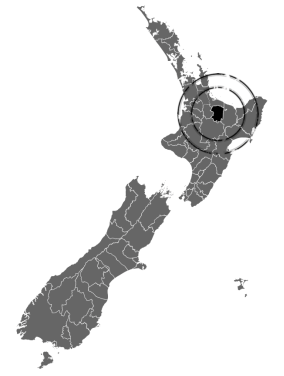

Lake Tikitapu, on New Zealand’s North Island, is said to be home to a mischievous taniwha, known to devour lone travellers in one gulp.

#

At the age of twelve Jamie visited New Zealand with her family. It was the holiday of a lifetime. She had heard of a freshwater lake which was so blue and clean you could see clear to the bottom on a sunny day, almost thirty meters of fresh water holding nothing more than eels and trout which grew to epic proportions but were impossible to catch. An enthusiastic, young Bulgarian waitress told Jamie of a young princess who dropped her greenstone necklace in the lake. The greenstone was said to rise from the depths, searching for a new princess. Jamie knew she would make an amazing princess.

Jamie demanded to go to the lake so her family stayed in a tiny cabin and endured days of driving rain, New Zealand summers unlike Jamie’s Kentucky ones. Her baby sister, Meredith hated the cold water so stayed bundled up with their mother. Jamie didn’t mind, it was less worrying about Meredith and more time to focus on her search.

Their accommodation was a simple wooden cabin in a tidy, sprawling campground, only a road away from the lake where a pontoon covered in fake grass swayed in the wake of the endless ski boats. The sun finally came out and for two days Jamie walked the perimeter of the lake and perfected her swimming and diving techniques, eyes wide in the clean, frigid water, searching, searching for the magical necklace which would make her a princess. Then a storm blew in and her parents could endure no more. It was time to move on. Before they could leave, Jamie escaped, slipping into her still wet bathers, the pink ones with a ruffle around the neckline, the one that made her feel like a princess.

Her father soon found her, and stood on the bleak beach, the rain lashing the green forest with streams that reached endless fingers out toward the water. He called for her to return but Jamie focused on the cold which was seeping deep into her bones, invading her core and taking what it wanted. Standing on the pontoon for a final time she turned toward her father who was motioning for her to come back, his hair clinging to his balding head. She loved him but craved the necklace more, would give up all her twelve years for a chance to become a princess.

A swelling in the water caught her eye. Were there other creatures in this water? The young Bulgarian waitress had whispered of the Taniwha that had once resided in each lake, twenty-foot monsters who feasted on those who entered their territory. They had scales and hair and webbed feet tipped with shiny talons that could slice a man in two. Jamie was scared until the young Bulgarian waitress had laughed and said it was all made up. As likely as the Loch Ness monster in Scotland.

Movement rocked the pontoon then tilted it unnaturally and Jamie fell, sliding into the water, hauled down by unseen hands or caught in an underwater rip which towed her further, deeper into the lake, a watery no man’s land.

Kicking and fighting for breath, Jamie was pressed, face down on the slimy lake floor, held against it as if someone was willing her to see. She opened her eyes when her scrabbling grasp found something smooth and hard. Then she was released, popping to the surface like a bubble in a mud pool.

Gasping, she heard her father yelling and realised she was face down on the pontoon, not in the water at all. Dazed and confused, uncertain of what had happened, Jamie pushed to her hands and knees, finding a carved greenstone in her palm. It was thicker than her hand, dry with a fine string of meticulously woven flax turning it into a pendant. She slid it around her neck and returned to the water and the beach, unable to process what had happened.

Her father reprimanded, not noticing the necklace hidden in the pink ruffles of her bathing suit.

She became ill later that day and spent the night in a small-town hospital.

During the night Jamie died and no one noticed. She was twelve and had come so close to becoming a princess. But the princess of legend had stepped forward and forced Jamie from her own body. Jamie little more than a memory left behind in a crystal-clear lake.

***

Anahera awoke with a jolt. She was in a white, claustrophobic room. The place stank, a smell that clutched at the back of her throat. Like duck fat left in the sun too long, it cloyed and sickened.

Her father and leader of their iwi, Tutanekai had slapped his fat lips together whenever she complained about rotting food, rubbing his wide stomach and booming about being hungry. Anahera had never liked ripe food, preferred what she could collect herself.

This place was loud, the echoing sounds clubbing her around the ears and making her jolt. She opened her eyes and gazed around in confusion. Where was the lake? Had she escaped? She had been stuck beneath the water for a long time and wanted to be free, no longer a princess or the reason her terrifying Taniwha would rear from the water in search of her, determined to exact his revenge against her father.

She wondered where the greenstone was. The necklace had contained her essence for all these long years and she loathed it as much as the lake and its tainted waters.

Sitting up, she took in the relieved pale faces around her. They were jabbering in some absurd language that was beyond her comprehension. These strangers looked welcoming enough but the eye watering odours and hectic lights, as bright as the sun, made Anahera wonder if she had made another wish to a false god. The last one had promised true love then had bought her a Taniwha, a beast for her beauty. Tuhirangi was no rangatira’s son, he was not of heaven as his name suggested, he was reinga, straight from hell.

This environment was overwhelming after the rib crushing water and the drone of the boats that churned the lake in mindless circles, leaving Anahera wishing them ill until the winter chill and silence left too much solitude. Anahera had not been born to loneliness, she was highborn and beautiful, everyone said so, her cold indifference solidifying her rank, and making her a prize desired by all others.

Atawhai, a neighbouring rangatira had negotiated on behalf of his firstborn son, Tuhirangi, when Anahera came of age. Together, prince and princess would unite the families, one day ruling a huge tract of fertile land and all four lakes. They would merge their power and control the biggest iwi the area had ever seen.

Anahera had never met Tuhirangi, no one had, but she daydreamed of her future husband, imagined how handsome he was, what a powerful man he would become, and how her power would grow along with his.

When Atawhai, his wife Ataahua and their entire iwi had arrived to confirm the union, they had bought with them not a human bridegroom, but a Taniwha. The beast remained at Atawhai’s back, the rangatira puffed with pride.

Without warning, Atawhai was slain by Anahera’s father, Tutanekai, and with a roar, the Taniwha had fled to the lake, the visiting iwi escaping into the forest. Anahera had been terrified but excited too, knowing her father would keep her safe. Confused, she wondered why her betrothed had not arrived with his father, what had become of Tuhirangi. The meeting was meant to introduce the two and Anahera had spent long weeks pining. Instead, she had been greeted—no, insulted—by the iwi’s evil pet.

Later, after food was cooked and the remnants put away, Anahera crept into a meeting, stunned to hear the elderly kaimatua discussing how the Taniwha was Atawhai’s firstborn in his true form, his god form. She was speechless. That creature was Tuhirangi? Who Anahera was to be joined with? Tutanekai was outraged that he had not been warned by his own kaumatua. Slaying a water god was desecration. How was Tutanekai to defend his iwi? And grave injustice had been dealt to Atawhai’s own family who would be mourning their kaumatua. Atawhai had wanted unification and peace and now he was bones.

Anahera had little interest in the politics and the ramifications from this day. She took to the lake, wondering if the prince in his god form remained near, her romantic heart imagining his man-form. Did he have a man form?

***

During the night, Anahera’s iwi was slain. Man, woman and child. Anahera was kept as a trophy, a gift to those who had lost their leader.

A foul, early morning wind blew as a young girl found her way to the ponga tree Anahera was lashed to. The child was around six and so skinny Anahera hated these people even more. There was no reason for a child to be hungry in this plentiful land.

“What’s your name?” Anahera asked the curious girl.

“Ataahua.” She peered at the ground, hands behind her back.

“Are you named after your queen?”

“Something like that.”

“You are beautiful. Now set me free.” Anahera commanded. “We will escape this cursed land and find those who will avenge my people. I will start my own iwi if no one will help, find lost souls or missing spirits to aid me.”

Anahera meant every word. She could see the path to her new future and it was bright. She would regain what was lost, recruit those strange bushmen who preferred solitude, and she would destroy every iwi who defied her.

The child, Ataahua spoke, “My son, he is afraid, remaining in the lake. You shamed him and destroyed his father. I convinced him you would accept his true form. Your love and compassion was meant to save us all. Instead you have failed.”

“Your son?” Anahera laughed. “You are a child. You are cursed by illness of the mind.”

The iwi emerged from the surrounding trees and listened to the young girl’s words.

“Not the mind.” Ataahua lifted her skinny arms, turning to her people, raising her voice for all hear. “Illness in the earth, our whenua. I am sent in both directions in time to find solutions. Backward and forward, I age and I become younger. Whatever the whenua needs. It asked for peace and instead your people fed it blood.”

“We should have been warned,” was all Anahera could think to say, her pride all that stopped her from crying with despair. Her purpose now was to keep her people alive in her mind until they could be avenged.

“The earth does not warn.” Ataahua laughed, her face changing, her nose lengthening as if unable to maintain the façade of a child any longer. “It prepares a story, we korero and we play our parts. Sometimes this makes the whenua happy, sometimes it does not.”

Anahera understood then, this wasn’t magic, it was insanity. “You want to kill me so get on with it instead of filling my taringa with your nonsense. Eat my bones, take my wairua, my spirit’s essence. I am nothing without my people. I will exact their revenge.”

This only made Ataahua cover her brown teeth with those dirty hands, amused. Her unblinking eyes not leaving Anahera who flinched at the colour, green like an angry lake. No one trusted green eyes. Anahera’s own iwi treating them like portents of coming evil.

“My son will have his revenge first.” Ataahua assured her, turning to the iwi before adding, “He will be patient, more than you could ever believe. The earth shall be washed clean and our people will return to power. Then these lands can do as they will. My role is now complete. I will return to the whenua and mourn in peace.”

The child, Ataahua, the mother of a Taniwha, turned to leave, the people parting to let her through. Something changed and she spun back, her face now a wrinkled old woman’s. “You wanted a warning?” she cried. “New people are coming. They will carve our lands without care for our histories and battles. They will create strange buildings to sleep and eat and shit in. They will scour our land for generations and still my son will await you. Heed my warning but understand your future cannot be changed. You cannot outrun fate or my boy.”

“What will it matter to me?” Anahera glared. “I will still be dead, as are my iwi.”

Her back now turned, Ataahua said, her voice echoing around the clearing, “My son is lost to me now. Taking to the lakes. Our people will perish in the coming generations, wiped out by battles and accidents. Then the pale people will bring more despair, bugs our eyes can’t see and vermin with illness in their blood. We will fade but you will endure. You are fated to wait until the earth is washed clean of people and your greenstone crumbles to sand. Only then will you redeem yourself in the eyes of my son and be worthy of his trust.”

“Your son? What about my iwi? Erased like they mean nothing.”

“My son was the way back to the gods!” Ataahua screamed, causing those around her to drop to their knees and avert their gazes. “I curse you,” she husked, trying to control her emotions. “You shall wait in the water, tied to your people by your greenstone. Then you have one chance to atone. If you fail then we all fail.”

Furious, the prestige of her station giving her more confidence than she deserved, Anahera called, “You will fail too. Your people have destroyed my future and I will never lift a finger to save any of them.”

Ataahua chuckled and Anahera got a glimpse of the age-old creature within the skinny child’s body. “Wait until you see the white man’s world. You will tire of these lakes and crave for my son to guide us all home. You will wish you had accepted him when he came so openly to you.”

With the korero ended, Anahera’s ankles were lashed to a huge stone with flax. A small waka rowed her to the centre of Lake Tikitapu and she was dropped over the side.

Fighting for her life, she hooked her fingers to the boat, screaming when the rowers beat them with paddles. Anahera held herself between two worlds as her fingers were pried away, the stone dragging her down. She held her breath for as long as possible then she let go, falling until the stone settled to the lakebed. Thinking of her iwi she took a moment to say goodbye to this hateful world then inhaled just as a creature swam from the gloom. She cared not for the monster. He would not save her after what had happened between their fathers.

The Taniwha came nose to nose with her. His forked tongue flickered against her lips, and as Anahera fell out of her mortal body she felt the gentle kiss of the Taniwha.

***

Anahera awoke with a start. The world around her was undulating, no sound touching her. Debris covered her body and as she sat up rotted flax bindings fell away. She was alive and now she was free. Her arms were weak but she pushed her way toward the sunshine and burst out of the water.

Warm sun touched her face and the Taniwha’s iwi loitered near the lake’s edge, yet when she reached the shore she could not leave the water, and the strangers would not look at her no matter how much she called to them.

Anahera had no choice but to wait, to despair and to wonder if death would have been better. The Taniwha circled but never came within reach. A threat? A promise? Was he imprisoned too or did he choose to stay?

For long centuries they lived together yet alone, his presence becoming a comfort.

Over time people came, different people with pale skin and strange hair. In winter they hid in their wooden shacks but when the sun shone strong they swum, not noticing Anahera circling beneath them, or the Taniwha watching them from the reeds. They built bigger houses and sat atop boats which plowed the lake, towing people with skin so pale Anahera wondered if they hated the sun.

Sometimes her greenstone floated away on its own. At those times Anahera followed to see where it might take them both. Sometimes people even touched it and Anahera’s hope would soar to be free of this cursed lake.

She only needed enough space to kill herself and end this torture. But every time, as if sensing something, the people would pull away before their fingers could close around her carving. She no longer remembered Ataahua’s words. No longer cared. She wished only to return to her iwi who were waiting for her, just out of sight.

Then a new girl came, searching, searching for something. Anahera tried to drag her to the depths of the lake, anything to burst her own boredom, but the girl slipped out of her grasp. Then the Taniwha tore the greenstone from Anahera’s neck, tossed it to the lakebed and dragged the child to it, pressing it into her palm when she floundered.

Anahera’s watery world was ripped apart, the sensation of being dragged from the lake was terrifying. As much as she wanted to end her misery, she had grown accustomed to the monotony. For long moments she was pressed inside the greenstone then with a burst of emotion she was released into the body of the pale girl in the strange clothing.

The child battled to retain control of her body, it was a bitter and long-lasting fight, and in the end, Anahera won because she wanted to live more.

The victory was short lived when Anahera awoke in a strange bed.

***

It took months for Anahera to adjust to her new life. The family returned to America, taking Anahera further from her lands than she ever dreamed possible. The flight left her traumatized and needing sedation, pills forced through her pursed lips by the woman who wept and called herself mum. Learning the new language was degrading yet they refused to learn hers, clapping with delight when she spoke basic words like a baby. She disdained them, found each one beneath her but needed time to learn this new world, so it suited her to remain quiet for now, docile and cared for. All the while her fractured soul cried out for Lake Tikitapu. Her Taniwha calling to her when she slept or forgot to concentrate.

Years passed in a blur of consciousness. She had forgotten the aches and pains of being human, the scrapes and hurts. It wore on her yet she endured, knowing this life would at least end, hopeful her soul would go with it and fuck the Taniwha and his hurt pride.

She started school and found it dull, her aggression toward the other children when they would not give her what she wanted an ongoing problem. Doctors were called, people talked about her feelings, but she had never been the same since the strange incident in New Zealand. It was like Jamie had died on that lake and someone else inhabited her body. But brain trauma was like that and what was to be done but get on with life.

Sometimes Anahera studied Jamie’s family, feeling no pity. They had lost one insignificant child when she had lost everyone except the Taniwha.

And still he called to her.

So Anahera made plans to be rid of this family who called her Jamie and insisted nothing was her fault. The younger sister was no fool. Meredith avoided her and snapped at her parents when they became overbearing. Anahera learned how to use books and the internet, she asked teachers about the history of New Zealand, her home, fascinated in what had changed since she had been cast to the lake. Remaining focussed she began preparing for the journey home. First she needed her greenstone which these strangers had hidden. When she questioned its whereabouts, she was told it had been tossed away for her own good. It was no use to retain trinkets from traumatic times, reminders of almost losing one held so dear. But she wasn’t dear, she was an imposter and she knew they felt it.

Anahera’s new body turned eighteen within a blink and she was afforded more freedoms. To claim her new life she needed to reach twenty-one, but time meant nothing, it passed with frenetic speed, willing her home to finish what had begun so long ago.

Trying several jobs was fruitless. Anahera was a princess and refused to be subservient. If the Taniwha could not force her to bow, she would not bend a knee to some fat, greasy girl who examined her chest and asked if she were a virgin.

The boys bored her. No matter how much she derided them they would not quit, as if her indifference was only a challenge to overcome. No one compared to the Taniwha who awaited her return; who would wait until the end of time for something she was still unwilling to give him. If he awaited her love he would wait for all eternity. She loved no one. Her emotions drowned along with her body back there beneath the waka. those paddles still bashing at her fingers.

Anahera was fired from that first job when the girl touched her in the back room. Pressing the girl’s forehead to the wall until she cried for release.

“Touch me again and I’ll show you the Taniwha in my soul,” she whispered, following her to the ground as she collapsed.

It took some convincing but Anahera made her way to university, drinking enough to pass, Jamie’s parents paying the bill. A website full of old men paid to watch her take her clothes off, she worked hard and saved hard and was on her way back to New Zealand a week after Jamie’s twenty-first birthday, the call of the forest, the lake and the Taniwha a constant ache in Anahera’s teeth. No matter how accustomed she had grown to this new world she would not miss it.

Not bothering to say goodbye to Jamie’s parents or her miserable sister, Anahera climbed aboard the plane with more surety than years before, it still disturbed her that people rode the skies in metal birds but she understood it was safe. Tied around her neck, right at her throat, Anahera’s greenstone was where it belonged. It had revealed itself when Meredith had returned from university, drunk and strung out on heartbreak, determined to antagonized Anahera, desperate for a reaction from her emotionless sister. The altercation got physical, yet Anahera had no urge to beat on Meredith. She meant nothing to her, was no part of her iwi.

Years of confusion burst from Meredith in a slurred tirade about how Jamie should have died in that lake, how she had ruined their family, how Jamie had gobbled all the attention leaving nothing for anyone else.

Anahera agreed. Their parents had spent so many years trying to fix their damaged daughter they had neglected the true one they had left.

Bored of Meredith, Anahera had punched her in the long-pointed nose. She had never become accustomed to the thin length compared to her iwi’s wide ones, and Meredith’s had exploded with blood. She bent forward, screaming until the parents came running, blaming Meredith for goading poor Jamie.

Her next sentence put Anahera’s scattered existence back on track.

“You know that thing isn’t Jamie. My sister died in a shitty lake in some far-off country. Give this stranger back her stupid rock trinket and let her go.” Meredith was sobbing now, alone on the ground while her parents observed her as if she were the stranger.

Anahera glared at the people who had suffered more than they would ever know, held out a hand and growled, “Give it to me, now.”

There was bickering, Anahera refused to join in. She never joined in, letting the anger and disappointment wash over her. These people knew little of utter destruction. It had taken her such a long time to understand her own loss and, although she regretted the suffering it had caused these people, she was helpless to change it.

Over the years Anahera had searched the house from top to bottom and followed in quiet interest as the father pried up a floorboard and withdrew her greenstone wrapped in newspaper.

Holding it to her lips, Anahera said, “My name is Anahera. My iwi was slaughtered a long time ago and your daughter sacrificed to allow me to return and avenge them. Do not follow me.” She turned away before guilt tugged her to turn back to the three white faces. “I thank you for caring for this body. I’m sorry for your loss.”

Then she was gone, uncertain if she was going soft with age.

***

Less than a week later she stood on the shores of Lake Tikitapu. It was dusk and autumn, few people around as the cool wind whipped at her hair and the lake surface.

Something near the centre of the lake caught her attention. It could have been a felled tree but Anahera knew better, and the wake, just under the water, heading toward her at speed, showed something alive and bigger than any freshwater fish or eel.

She stepped into the water, ignoring the chill, her heart thudding, catching the scent of the surrounding pines, the ugly trees which had replaced her fallen forest of kauri.

The water was at her waist when the huge head arose before her. Not within touching distance but close enough she could note every mark and scar on his big body.

“This will end.” She said in her native tongue. The Taniwha shook his head, struggling to shift his jaw to form words.

“This ends when I say it ends,” he growled, the dark eyes hard with ongoing hatred.

“Then I cannot stay with you.”

His eyes became small with suspicion. “You lie. All your people lie.”

“My people are dead. So are yours. There is only you and me. Kill me to appease your wounded pride if you must. Set us both free.”

He lunged, snatching Anahera by a wrist with one of his clawed hands. Ignoring the cuts to her wrist, she didn’t fight, instead letting herself be towed to the centre of her lake, grateful to be home, to feel her beloved water fill Jamie’s lungs as her body was tossed around as if by a dog, shaken, pushed and pulled.

She awoke on a tiny beach which would not be there if the lake were any higher. Beside her lay a man of around twenty. Anahera wanted to hit him, to strangle him, to press her greenstone right through his black, evil heart. Instead she stood and shed her wet clothes, draping them in a tree to dry.

Turning to the man, she asked, “What now? What was your big plan? You called me back, you got your revenge. My people are gone. You have blamed me for what was done to your father, even though I was just a child. So what now?”

His eyes were flicking between warm and brown to cold and black with a milky sheen. His jaw lengthened as did his teeth. Then he swallowed and his Taniwha retreated. “You must want me,” he said, “It was foretold.”

“I don’t want you,” she sighed, stepping back into the water and rinsing her hands. She was aware she was bending over in front of this man, both naked, she didn’t care.

“It is not your decision to make,” he told her, eyes sliding back to the water.

“Why?”

“Your family must pay.”

“My family are all dead. Our time is over, we lost everything, the white man took it.”

“I don’t care about the white man.”

“You don’t care about anything.” She frowned. “It’s time for you to set us both free. Whether you wish to stay here is up to you. But let me go.”

Those dark eyes shifted, confused.

Anahera asked, “How long since you regained your man form?”

“I am the Taniwha.”

“No, you are a man. You can’t even remember why this happened, can you? You trapped us here because your mother said you should be offended. She’s dead, long gone. It’s your life now. What do you want to do with it?”

“I am the Taniwha. It is my purpose.”

“No, it is what you are. It is not your purpose.” Anahera lifted the greenstone from around her neck and slashed at the man. The sharp edge bit deep into his bicep and he reached out and snatched her hair, pulling her close.

“You are mine.”

“I would rather die.”

“You are mine,” he repeated and Anahera’s stopped up emotions broke free. In one move she pulled out of his grasp and slashed out at the Tuhirangi’s throat. It split wide yet his face didn’t change as he walked from the sand and into the water, the greenstone in his palm, intricate carvings flashing brilliant green that the overcast day could not explain.

His form changed as he strode into the water, the blood colouring his torso. When he was chest deep he turned and pulled his arm back, then let the greenstone fly with one hard throw, the heavy stone sank into Anahera’s chest, piercing her heart and pushing her from Jamie’s body.

Gasping for breath she no longer needed, Anahera’s scream echoed around the lake but no one could hear her. On the beach she found a body collapsed. Unable to turn away, she remained until Jamie’s body was found by a dogwalker then collected by men in blue uniforms. What would Jamie’s family feel when they were informed of their daughter’s final demise. Would it give them closure? Would they turn their attention to their true daughter? Or was the relationship ruined, family links torn apart by guilt and time?

Taking to the lake she drifted for a long time. Her thoughts scattered as a young girl stepped into the frigid water, her one-piece suit bright enough to catch Anahera’s attention. A young father rocked a baby, tired and annoyed, not paying attention to his intrepid daughter who looked around the age of twelve.

This time Anahera would make it work. She would find a way to be rid of this curse.

At her back was the Taniwha. She turned to him, the cut at his neck now a thick scar to adorn his battered body. They glared at each other for several long moments before Anahera kicked away, racing for the shore and the girl, their hands touching, the girl grasping the greenstone as it was thrust into her palm. Her grin as she emerged from the lake on a whoop of delight was soon cut off as Anahera flooded her mind.

It took two days before Anahera awoke in the hospital. This girl was a fighter but she was collateral to Anahera who would work harder this time to find her way out of this curse.

***

Back in the lake the Taniwha circled his territory, awaiting the time his mother had forewarned, when Anahera would be broken enough to come to him. Only then would he set them both free, after the time of people.

He was patient, his Taniwha form not seeing time as a line but a guide for his future. The outcome was undeniable. His children awaited Anahera’s return, protected beneath the earth. They too were patient. His mother whispered in his mind, reminding him of his purpose. To return their people to the world when it was flushed clean and they would reclaim all that had been lost.

They had nothing but time.

About the Author:

Casey Campbell hails from the mighty Waikato in New Zealand and spends most holidays in the beautiful lakes of Rotorua. She is a librarian, contributor to several short story anthologies and has published seven full length novels. You can mostly find her on Instagram at caseycampbellwrites.

ABOUT DEADSET PRESS

Deadset Press is an independent publisher of incredible speculative fiction. We provide publishing pathways for emerging writers from Australia and New Zealand, and aspire to shine the light on unique and diverse voices.

You can learn more at:

ALSO BY DEADSET PRESS

Annual Anthologies

Beginnings: Aussie Speculative Fiction Anthology Vol. 1

Journeys: Aussie Speculative Fiction Anthology Vol. 2

Revolutions: Aussie Speculative Fiction Anthology Vol. 3

––––––––

Drowned Earth

Prequel: Shards of Silver by Alanah Andrews

The Rise by Sue-Ellen Pashley

Fire Over Troubled Water by Nick Marone

Submerged City by Austin P. Sheehan

Tides of War by Marcus Turner

The Jindabyne Secret by Jo Hart

River of Diamonds by S. M. Isaac

Salvaged by C.A. Clark

Emoto’s Promise by Shel Calopa

Charity Anthologies

Stories of Hope

Stories of Survival

––––––––

The Zodiac Series

Capricorn (The Zodiac Series #1)

Aquarius (The Zodiac Series #2)

Pisces (The Zodiac Series #3)

Aries (The Zodiac Series #4)

Taurus (The Zodiac Series #5)

Gemini (The Zodiac Series #6)

Cancer (The Zodiac Series #7)

Leo (The Zodiac Series #8)

Virgo (The Zodiac Series #9)

Libra (The Zodiac Series #10)

Scorpio (The Zodiac Series #11)

Sagittarius (The Zodiac Series #12)