Metaphysics: the origin of becoming and the resolution of ignorance

ORIENTATION: THE LANGUAGE OF METAPHYSICS

Neoplatonic metaphysics does more than tell a story; it is illocutionary as well as indexical, in so far as it tells us how to see the world and how things got to their present state, and offers a corrective for our current condition, namely ignorance.1 Neoplatonic metaphysics seeks to explain appearances (the world) in a way that simultaneously calls that very thing – the world – into question. Accordingly, the metaphysical discourses of Neoplatonism move in two directions: they are constructive, affirming and revealing a vision of reality that is not yet in evidence. Plotinus attracts the reader into the project of uncovering that reality by offering instructions (see Rappe 2000) in how to work with the text or doctrine: “Shut your eyes and change to and wake another way of seeing”;2 “Let there be in the soul a shining imagination of a sphere”;3 “One must not chase after it, but wait quietly til it appears” (Enn. V.5[32].8.4). These discourses are also deconstructive and apophatic. Plotinus assists his reader in denying and removing a vision of reality that is already too much in evidence: “How to see this? Take away everything!”4

Neoplatonic metaphysical treatises often catalogue primary and secondary principles (an approach that contemporary scholarship also emphasizes).5 The assumption is that reality is graded and that some things are prior to, that is, are more real, than other things. Yet it could well be that in its refusal to downgrade appearances, the phenomenal world, to mere appearance, Neoplatonism runs the concurrent risk of relying overmuch on the explanatory apparatus of cause and effect. Addressing itself to the reader qua soul (Enn. VI.4[22].14.16: “Who are we?”) (see Remes 2007), this kind of discourse seeks to explain the place of the soul in terms of the larger reality, the causes or first principles, whose product it is. But if the reader takes up a position of being or identifying with soul, and metaphysics is a description of how the soul returns to the first principles, then the very point of metaphysics, as a corrective to what the Neoplatonist sees as extopic or exotic – the embodied, separate self and its temporally defined existence6 – is lost. For this reason, the language of Neoplatonic metaphysics is best understood as promissory, offering a glimpse of reality, a prelude to genuine knowledge.7

It would not be going too far to suggest that Neoplatonic metaphysics, as a discursive construction, is ancillary to a discipline of contemplation that is not in itself confined to or even concerned with causal explanations. To the extent that Neoplatonic philosophy and its study rely on arguments for a first principle, these in themselves do not constitute the end product of this philosophy. Accordingly, it may be very tempting to reduce Neoplatonic metaphysics to an explanatory system that achieves consistency, complexity and flexibility over time, but its purpose can never be reduced to the creation of such a system. No matter how rooted in the authority of Platonic exegesis or in the systematic interpretation of Platonic texts, the greatest truth on which Neoplatonic metaphysics relies is none other than the direct reality of the person who approaches it in search of the truth.8 Therefore, paradoxically, the purpose of Neoplatonic metaphysics, orienting the student towards the real, often breaks in on or is at times in tension with its existence as a self-standing explanatory discourse.

THE CENTRAL PROBLEM OF NEOPLATONIC METAPHYSICS: ONE OR MANY?

Given that Neoplatonism directly bases its entire philosophical outlook on the positing of a transcendent unity, the One beyond being,9 it makes sense that the dialectic of One and Many forms a nucleus within Neoplatonic metaphysics as it develops over the centuries. Plotinus and the Neoplatonists subsequent to him locate the difficulty over the derivation of all things from the One as the central problem in metaphysics:

But [soul] desires [a solution] to the problem which is so often discussed, even by the ancient sages, as to how from the One, being such as we say the One is, anything can be constituted, either a multiplicity, a dyad, or a number; [why] it did not stay by itself, but so great a multiplicity flowed out as is seen in the real beings and which we think correct to refer back to the One.

(Enn. V.1[10].6.3–8)10

Briefly, the puzzle can be described as follows: if the One, which by definition lacks multiplicity, differentiation, qualities, attributes and even being, is the highest and most complete identity, then how do the Neoplatonists account for the proliferation of various kinds of being, the very fact that there is life, mind, intelligence in all of their diversity? If we say that all of these beings are “from” the One, then what causes their departure from this ultimate identity? If the One is the cause of all beings, and this causality is conceived as a participation of all things in the One, then the transcendence of the One is compromised at the outset. And yet if the One remains isolated in its transcendence, this raises the question of how it communicates reality to any of the other aspects of being.

From its inception, then, Neoplatonic metaphysics faces a dilemma: either all that is must ultimately reside within the One or else the One produces whatever else arises as outside of itself. To choose the first option allows a solution that implies that there is something in the One that is not the One. The second option places emphasis on the causal powers of the One. The problem with the first option is that whatever is in the One is simply One; how can there be distinctions in the primordial unity? The problem with the second option is that it entails the diminishment of effect with respect to its cause (otherwise, lesser realities would be equivalent to the One),11 and we will have no way to account for the origin of this unlikeness: how can absolute unity give rise to multiplicity in the first place?

In what follows, I attempt to survey a variety of answers to this dilemma, tracing a dialectical path through the history of Neoplatonic metaphysics. Plotinus inaugurates a tradition of responses to this dilemma in terms of his most fundamental intuition: that the One’s productivity is contemplative by its very nature.12 His metaphysics of light13 emphasizes the place of self-knowledge, self-revelation and theophany in understanding the relationship between world and principle. By contrast, Proclus’ metaphysics of eternal being emphasizes the structures and hierarchies of the intelligible order, unfolding along the lines of a causality or of a transfer of power (dynamis, the capacity to effectuate reality). Power (as we find it in Proclus’ system) represents both a departure from a greater reality and the production of a lesser reality.14 Thus to bring about the effect is to reveal a possibility that it was latent within the higher order; it is to diminish that same order as well as to augment it.15 Given these fundamental tensions operating in the Proclean metaphysics of being, later Neoplatonists went on to treat them through a perspective that skirted the problem of being altogether. Damascius rather institutes a metaphysics of non-being,16 in his insistence on a radical return to the origin, conceived not as One or Good, but as the Ineffable, as the unconditioned ground of reality, the first principle that does not just underwrite the metaphysical enterprise as such, but simultaneously seeks to tame the arrogance, so to say, of that very enterprise. These three kinds of discourse, of light, of being, and of emptiness or of non-being, then, reveal the creative directions or orientations that together constitute some of the wealth of Neoplatonic metaphysics.

PLOTINUS’ METAPHYSICS OF LIGHT

The causal role of the One as source of all subsequent stations of the real is rooted, for Plotinus, in the contemplative nature of the One’s activity, if it can be said to have an activity (Plotinus speaks variously about this possibility).17 Uniquely among all Neoplatonic thinkers, Plotinus emphasizes the relationship between One and Intellect as the first dimension of the manifest world, exploring the continuities and affinities between the One as what Plotinus calls “pure light” and “eternal awakening”18 and Intellect as the actualization of that “light”. By contrast, for Proclus, the intelligible realm, the realm subsequent to the One, is first conceived in terms of Being. By dwelling for a moment on this contrast between Plotinus and Proclus, who inverts the Plotinian order of Intellect and Being, understanding that the objective formations of Being take priority over their status as living intellects, we come to understand the inaugural point of this metaphysical tradition as a whole.

Plotinus employs three different models for understanding Intellect’s relationship to the One (thereby anticipating Proclus’ metaphysics of procession, remaining and reversion): the inchoate Intellect; the actualized Intellect; and the hyper-Intellect.19 Most often he characterizes the first movement, procession, as a “shining out”, or an “irradiation” (perilampsis; epilampsis). For example, in Enn. V.1[10].6.26–9, he discusses the emergence of the intellect from the One as perilampsis, the “effusion of light”, which circumradiates the sun.20 Plotinus is inclined to front the Republic, its images of the Good as source of intelligibility, and the epithet, agothoeides (“having good as its nature”; “affinity with the good”, e.g. Enn. VI.7[38].15.9, 16.5) (Bussanich 1988), as the primary textual authority for his understanding of the derivation of Intellect from the first principle.21

This metaphor, the sun and its radiance as applied to the first principle (“the first activity flows from it like a light from the sun”, Enn. V.3[49].12.40), invites interrogation: into what does this One, the first principle, shine? Into what place does its radiance arrive? The implications portend a paradox: at the very beginning of manifestation, the One has nowhere else to shine; nothing other than itself to illuminate. Plotinus writes in the same essay, still developing this metaphor of circumradiant light, “the One does not push away its outshining from itself” (Enn. V.3[49].12.44). So at the very inception of the One’s procession, even before Intellect arises, there is a question that defies the metaphor and the metaphysical theory that undergirds it. If we are speaking about the One, by definition there can be nothing external to it; the outshining is not something that can function outside the One. Therefore the One, in giving rise to manifestation, is thereby engaged in (a paradoxical) self-disclosure; in functioning as the ground of all things, the One does no more than reveal itself to itself, discovering even as it gives rise to its own infinite possibilities. Plotinus writes of the One’s own self-absorption as follows: “Now nothing else is present to it, but it will have a simple concentration of attention on itself. But since there is no distance or difference in regard to itself, what could its attention be other than itself?” (Enn. VI.7[38].39.1–4).

In a well-known text, Plotinus offers the most compressed of creation stories: in it, he employs the Platonic language of images and alludes to the Republic, certainly, but most importantly he assimilates the generation of the intelligible world to the act of vision, in keeping with the contemplative foundation of the One’s activity:

But we say that Intellect is an image of that Good; for we must speak more plainly; first of all we must say that what has come into being must be in a way that Good, and retain much of it and be a likeness of it, as light is of the sun. But One is not Intellect. How then does it generate Intellect? Because by its return to it, it sees (heōra): and this seeing is Intellect.

(Enn. V.1[10].7.1–6)22

The last sentence, translated neutrally above, is one of the most controversial in all of the Enneads, and can be more tendentiously translated as: “Because by Intellect’s return to it [the One] [Intellect] sees”,23 or alternatively as “Because by turning to itself the One sees” At stake in the differences between these translations is the purported agency of the One. The second possibility faces the difficulty that the One cannot undergo a reversion to itself, when it has never been described as having proceeded. The first possibility faces the difficulty that the Intellect has not yet arisen in the first place; this translation would seem to defer, rather than offer, any explanation for its origin. Again, to say that Intellect just is equivalent to the seeing of the One suggests the opposite of what has just been said: the One precisely is not Intellect (and it is because the One is not Intellect that the question asked here is “how does the One generate Intellect?”) As the ambivalences are built into the Greek and the grammatical subject of the verb, heōra (“sees”), is entirely irrecoverable, of necessity we ask who is doing the seeing: is it Intellect or the One? In hinting that the One turns towards or into itself, that it enjoys a form of self-awareness that yet reverberates as a separate identity in Intellect, Plotinus offers an account of the relationship between One and Intellect. As I will try to suggest in what follows, Plotinus wants to make clear that the intelligible world does not obscure the One’s nature; instead, its very function is to allow the One to fully recover its own nature.

The procession of Intellect is equivalent to inchoate Intellect, an outflow that is the external activity of the One; yet Intellect also has its own (internal) activity, which it realizes when it reverts to the One and actualizes itself as a knowing principle in relation to an object of knowledge. Plotinus describes this process in the following passage:

But how, when that [sc. One] abides unchanged, does intellect come into being? In each and every thing there is an activity which belongs to the ousia [the being of something] and one which goes out from the ousia, and that which belongs to ousia is the activity which is each particular thing, and the other activity derives from that first one, and necessarily follows it in every respect, being different from the thing itself.

(Enn. V.4[7].2.27–30)24

Here we have a description of the self-determination of Intellect as a separate hypostasis. According to Plotinus, the internal activity of an entity is identical to the ousia, the being or essence of that thing, whereas what that internal activity consists in is actually a contemplation of or reversion towards what is higher (A. C. Lloyd 1987). In the case of the One itself, there can strictly be no activity in it, since it is beyond essence, nor is there anything higher for it to contemplate. The One, then, contemplates itself, and yet it cannot do so inasmuch as the One is not an object of thought. Therefore, in the One’s turning towards itself, Intellect emerges. To the extent that the One initiates this self-directed activity, it gives rise to a phase of intellect known as “inchoate” Intellect.

In order to find language for the notional distinction between the One as thinking itself and the One as quasi-object of its own thought, Plotinus’ astute reading of Plato’s Parmenides plays an important role: Plato distinguishes the consequences of the assertion that the One is, both for the One itself and for others (cf. the so-called fourth hypothesis). In Plato’s Prm. 156b6–159b, we read: “If the One is, what are the consequences for the others?,” which is elaborated further at 157b5–7: “We have next to consider what will be true of the others, if there is a One. Supposing then, that there is a One, what must be said of the things other than the One.”

The internal act of a given reality is, in some sense, what it is in itself; the external act is how it is for others. But in saying this much, we have already altered the nature of the One: the One cannot be something in itself, since this of course implies containing its own activity, its own ousia, which, Plotinus indicates, is not present in the One. And yet, in containing itself, it will be subject to the distinction between self and other, between the container and what is outside of that container. It is in this sense that scholars have made a point of emphasizing that, whenever the Intellect reverts to itself, that is, whenever inchoate intellect “sees” the One, what it sees must be an image of the One.25 Thus inchoate Intellect functions as a kind of intelligible matter, whereas the image of the One functions to limit, define and actualize the Intellect proper.26 He reaches back into Aristotelian27 metaphysics, physics and psychology. Here the One (either in itself or as seen by the Intellect) becomes the object of the Intellect’s vision or intellection; it is the reality or existence that actualizes or makes real Intellect’s apprehension of its object. In so conceiving its object, Intellect actually generates Being or beings: “in seeing that it had offspring and it was directly conscious of their generation and their existence within it” (Enn. VI.7[38].35.33).28

Above I suggested that there are Plotinian analogues for Proclus’ more precise scheme of procession, reversion and remaining.29 We have already discussed procession and reversion as they relate to the genesis of Intellect. “Remaining in the cause” implies that the external activity that becomes the effect does not exhaust the cause; this feature of the causal triad is allowed, in Proclus’ metaphysics, through the law of undiminished giving, captured in ET prop. 75, according to which the cause transcends the effect. In Plotinus’ case, however, we are more concerned with the nature of Intellect as it manifests both the capacity to create, through its intellection, the realm of being, and through its transparency, so to speak, the capacity to remain free of that same creation.

We encounter the hyper-intellectual phase (equivalent to remaining in the cause) of Intellect in Intellect’s ascent back to the One, into union with the One.30 This aspect of the Intellect is what Plotinus calls the loving Intellect (nous eron) or the inebriated Intellect (nous methystheis, Enn. VI.7[38].35.25):

[Intellect then has one power] by which it looks at what transcends it by a direct awareness (epibole) and reception, by which also before it saw only, and by seeing acquired intellect and is one. And that first one is the contemplation of Intellect in its right mind, and the other is Intellect in love, when it goes out of its mind “drunk with the nectar”.

(Enn. VI.7[38].35.19–25, trans. modified)

Astonishingly, Plotinus tells us that the hyper-noetic intellect does not think (Enn. VI.7[38].35.30) (see Bussanich 1988: commentary ad loc.): that there is an Intellect that remains without thought. Moreover, this side of Intellect always belongs to it: “Intellect always has intellection and always non-intellection” (Enn. VI.7[38].35.30). The loving Intellect in discovering the Good finds that it sees the Good not as its object, but rather it becomes a seeing that has no object: “while the vision fills his eyes with light it does not make him see something else by it, rather the light itself is what is seen” (Enn. VI.7[38].36.20). This is the hyper-noetic phase of Intellect, which encounters the Good as its very own nature (light). Whether or not the inchoate Intellect and the Intellect in love are one and the same Intellect, it is clear that Plotinus’ language often leads us to link the two aspects.31 For example, O’Daly (1973: 166) quotes Enn. VI.9[9].4.29–30: “when someone is as he was when he came from him, he is already able to see as it is the nature of that God to be seen”. Here at least it would seem that Plotinus emphasizes the simultaneity of the two phases of Intellect, which we might call before and after procession, which constitute together what Plotinus calls the One’s self-arrival. Intellect then proceeds, remains in, and reverts to its cause, the One, simultaneously. When Intellect returns to the One as loving Intellect, it rediscovers its capacity to know, even when there is no object of vision. Hence, in releasing all the objective conditions, it no longer exercises intellection. In Enn. III.8[30].9.29, we learn that Intellect takes a backward step from its identity as Intellect: “the intellect must return, so to speak, backwards, and give itself up.”

The intimacy that Plotinus insinuates between the Intellect and the One tells us a great deal about the nature of Intellect or wisdom and its objects. The nature of wisdom is to be empty: as Plotinus tells us, that kind of Intellection is non-intellection. The inward motion of the One, its own self-permeation or arrival within itself, is recuperated eternally, as the Intellect continually remains grounded in the One, entirely unconditioned. Intellect originates in this openness, freed from all objects – profoundly contrasting with the proliferation of beings that is for Plotinus the other, generative side of Intellect. In looking to the Good, Intellect thus is thinking, eternally generating its prolific offspring; in discovering itself as the Good, Intellect is not thinking, eternally free; as Plotinus puts it, “about to see (emelle noein)” (VI.7[38].35.33). The upshot of this discussion is that always and everywhere, Plotinus emphasizes the contemplative ground of the metaphysical enterprise as such: first and foremost, because reality is none other than the One’s own self-disclosure. Further, the nature of wisdom or Intellect as it arises from the ground of this fundamental reality is empty – utterly without content or distinctions, located nowhere and with no object. Only by encountering wisdom in this pristine form can metaphysics be understood – as a contemplative realization, not as an explanation. Of course, this kind of intimate assimilation between the One and Intellect is not just the initial phase of the Intellect’s emergence from the One. It has simultaneously achieved its proliferation in the plurality of beings, in the world of forms, and in the multiplicity of Intellects, all derived from its differentiation from the One. But it never loses the capacity to become transparent, free from objects, free to give rise to objects.

PROCLUS’ METAPHYSICS OF BEING

In moving towards Proclus’ metaphysics of Being and away from Plotinus’ metaphysics of light, we necessarily turn away from the affinity of the One and Intellect. For Proclus, as we have already had occasion to note, what arises immediately after the realm of the One is not primarily understood as Intellect, but as Being, which Proclus explores in the terms of a series of investigations into principles of causation. In the interests of coherence, explanatory consistency and fullness, he develops an account, in the Elements of Theology, that seeks to derive the entire ontological order from one fundamental axiom: “Every plurality participates somehow in unity” (ET prop. 1).

In studying Proclus’ metaphysics of Being, we turn away from what we saw in Plotinus was a heavy reliance on the Republic to focus on the Philebus as an important source text for Proclus. Proclus associates the three principles of Phlb. 27d, limit, unlimited and mixed (peras, apeiron and mikton), with the first stages in the devolution of reality after the One.32 In the metaphysics of Proclus, peras and apeiron constitute a dyad after the One, becoming conduits of unity and multiplicity, and introducing the possibility of reality outside of the ineffable first principle. The third nature, the Philebus’ Mixed, introduces a subsequent stage of development, which Proclus and Iamblichus understand as the intelligible world, or the realm of Being.33 Thus the three kinds of Plato’s Philebus are the fulcrum around which reality proliferates and the hidden fullness of the One pours forth into the world of manifestation.34

For Proclus, peras and apeiron are related to a Pythagorean interpretation of Plato’s Philebus. This interpretation functions as the basis for his explanation of how the world of multiplicity, expressed as the gradations of Being, arises from the absolute One. The dyad therefore constitutes a manifestation of the hidden or latent power of the One, that is, its all-possibility. As Van Riel has demonstrated, Proclus actually coins a word, ekphansis (“manifestation”), as a way to display the relationship between the Dyad (peras and apeiron) and the One.35 The nature of the One is revealed or is made manifest in what for Proclus constitutes the first Dyad which he calls, in a manner that might remind us of Plotinus, an ekphansis, “a showing forth of the nature of the One”.36 Essentially, for Proclus peras and apeiron function like form and matter; their product, a synthesis of the infinite power of the One together with the unity of the One, is a compound; that is, Being. Therefore, the One has, as it were, elements that in some sense share its realm; by denying that there is any potency, any dynamis, in the One, Proclus must transfer this function to the primal limit that functions with the primal limitlessness to, in a sense, produce the realm of Being (PT III.9.31).37

Proclus defines the One as the cause of all things, as causing that which it itself does not possess, through the doctrine according to which “every cause properly so-called transcends its effects” (ET prop. 75). Another important source text for this principle, at least in so far as it applies to the metaphysics of the One, is the Parmenides, the interpretation of which, he tells us, is owing principally to Syrianus. Proclus says of the One, “everything then, which is negated of the One proceeds from it. For it itself must be no one of all other things, in order that all things may derive from it” (in Prm. VI.1077.29–31 [Steel]). Proclus suggests that all that the second hypothesis of the Parmenides asserts is denied by the first, and indeed, that the very negations of the first hypothesis actually cause the corresponding positive assertions to be found in the second hypothesis (in Prm. VI.1075). Thus the One produces by means of negations; this is very strange language, and it may seem to be much less satisfactory than even Plotinus’ metaphorical accounts of generation, which refer to the undiminished giving of the One, of its giving birth.

In addition to using the Philebus and the Parmenides as his source texts, Proclus’ interests in the logic of causation extend further into a series of principles that formalize Platonist intuitions concerning image and archetype, matter and form, and the reciprocity of the Good with respect to all other members of reality. Form acts as cause and image imitates that form (Phd. 74e1); the Good extends providential care in the form of introducing Being and intelligibility (R. 508e), and acting as the teleological goal of every soul (Smp. 205a5). Proclus then fuses the fundamental Platonic relationship, between the Form and its image, with the Aristotelian conception of the transmission of cause, to create a causal principle that pulls his system in two competing directions. This principle, that the cause is necessarily greater than the effect (ET prop. 75.1–2: “Every cause properly transcends its resultant.”), relies both on the explanatory capacity of causes to bring about realities that express (imitate or revert to) their sources, and on the Platonic axiom that the image is less real than the archetype.38

Above we saw that in the metaphysics of Plotinus (at least the initial stages of reality’s expansion), not only is there an emphasis on the affinity between Intellect and the One, but the activity of Intellect flows in two directions: the shining out and the self-arrival, two sides of the same act, so that there is no departure from the nature of the One, a perspective that Plotinus underscores in his metaphors that convey the undiminished giving of the One (the inexhaustible font; the radiance of the sun). The Intellect, for Plotinus, reverts upon the One, refracting the light of the One into an infinite series of intuitions, each intuition discovering its object as fully real, as the eternal ground of its own capacity to discern reality. For Proclus, too, the entire procession of effects from their original cause flows backwards towards the source in a circuit that ultimately allows the lower to function as the mirror of the higher. Proclus describes this circuit most succinctly in ET prop. 35: “every effect simultaneously proceeds, remains, and reverts to its cause”

How, then, does the cause return to or revert upon its effect? We have glimpsed the Platonist intuitions that inform Proclean metaphysics in mimēsis, the imitation of the cause (the effect preserves likeness with the cause), and in eros (the effect has an erotic disposition towards union with the cause). But in order to understand the process of reversion in greater detail, it is necessary to discuss the vertical and horizontal gradations that allow both differentiation and ranking among similar kinds of reality and distinction and hierarchy between superior and subordinate kinds of realities. For Proclus, multiplicity, the proliferation of effects from their causes, can be studied as internal and external, as uniform and hetero-form procession, or as horizontal and vertical procession. In a way that might put us in mind of Plotinus’ theory of two acts, Proclus refers “to procession and multiplication as the external activity of an entity, and reversion and unification as its internal activity” (A. C. Lloyd 1987: 33).39 At ET prop. 108, Proclus sketches these two kinds of profusion: “Every particular member of any order can participate the monad of the rank immediately superjacent in one of two ways: either through the universal of its own order, or through the particular member of the higher series which is co-ordinate with it in respect of its analogous relation to that series as a whole” (ET prop. 108).

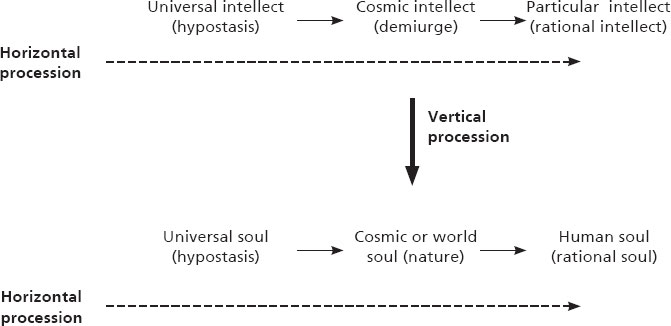

This sentence is imposing and sounds quite abstract, but a simple example might illustrate these two kinds of procession. Suppose that Intellect proceeds horizontally into various lesser forms of intellect (the demiurgic and human intellects). Suppose further that Intellect also proceeds vertically (declines) into a lesser hypostasis, Soul, while the Soul hypostasis itself proceeds horizontally into the various members of that hypostasis.

Here we have two successive transverse series or strata of reality proceeding from their respective “monads” or universal terms, Soul and Intellect: thus we have two kinds of procession, one, for example, of Soul from Intellect (vertical) and one, for example, of World Soul from Soul (horizontal). What then accounts for the “declination”, as Proclus terms it, from One to Intellect, from Intellect to Soul, and from Soul to body? Proclus will need to invoke the principle that the cause is greater than the effect, together with the principle that every multiplicity participates in a unity that is prior to it.

Figure 11.1 Vertical and horizontal procession.

Now, each member of these series can revert in each of two ways: vertically (Soul reverts to Intellect), or horizontally (Soul reverts to or within its own hypostasis, becoming in a sense most profoundly itself). Either way, Intellect’s reversion to the One (and we saw this in the case of Plotinus’ inchoate Intellect reverting to the One and becoming actualized Intellect) does not result in the disappearance of Intellect. Instead, the stage of reversion enables the effect to become most distinctively itself: it achieves its essence, its definition, its formal nature, by engaging in the internal act that is most appropriate to itself. For Proclus, reversion to the cause takes place according to the three channels or aspects of the intelligible order: Being, Life and Intellect. Thus, reversion to the cause results in the complete realization of, for example, the human soul as a living, intelligent being possessed of self-knowledge and fully cognizant, as well, of its eternal source.40

We see that not only does Proclus suggest that the One is the cause of all things, and that every cause transcends its effects, but he also provides a “circular” model of causation according to which, “every effect remains in its cause, proceeds from it, and reverts upon it” (ET prop. 35).41 He discusses this spiritual circuit in his in Prm. 620, when he reminds the reader that “every plurality exists in unity”. Thus, when it comes to understanding the fundamental relationship between the transcendent principle and its manifestations, Proclus insists that there is an unparticipated aspect of each and every hypostasis, including the One. Moreover, the primary sense of the hypostasis is its subsistence as what Proclus calls a “whole before the parts” (ET prop. 67).

Yet the strength of Proclus’ system is also perhaps its weakness: the terms of the procession can never be reversed, as reversion itself entails a strengthening of identity with respect to the being that reverts to the higher, receiving its good and fulfilling its nature through that very reversion. Proclus’ soul, in reverting to its ultimate source, the One, is able, according to the metaphysics of Proclus, to realize a kind of unification with the divine, an act that takes place when the soul actualizes its own “centre”, as Proclus calls it, but reverts to the transcendent. As he describes this process in the in Prm., Proclus suggests that the formal boundaries between soul and first principle in fact strengthen the soul in its otherness, its ontological station apart from that principle:42 “We must awaken the One in us in order that we might be able, if it is permissible to say this, to know somehow what is like [us] with what is like [that], within the parameter of our own ontological station (taxis)” (in Prm. 1081.5).

Here we glimpse a moment that breaks free of merely metaphysical discourse: earlier in the passage Proclus warns us that this knowledge can never occur through merely discursive capacity. Nevertheless, Proclus emphasizes the ontological distance between the One in us and the One qua transcendent principle. The upshot is that even this highest form of knowledge, when the soul awakens the faculty that is most akin to the one, also at the same time recommits the soul to its identity as other than the One; as ontologically inferior and as eternally, even irremediably, belonging to a different order or rank. In ET prop. 31, Proclus repeats what is essentially Plotinus’ understanding concerning procession and reversion: procession grants existence; reversion grants essence. As we saw, the reversion to the One in Plotinus’ philosophy allows Intellect to become not the One, but rather itself: the Indefinite Dyad, intelligible matter, is defined through its object, the One as determined or conditioned by the very nature of Intellect. Likewise, the reversion to the cause allows the effect, in Proclus’ philosophy, to realize its own highest nature; to become more itself.

Yet Neoplatonism is not just an exegetical metaphysics that attempts to reify the hypotheses of Plato’s Parmenides. This manifestation of the One in all things is, ultimately, just the life of the soul, as it undertakes the journey of awakening to its source in the One, and also its cosmic mission of returning the multiplicity back into the source. We have seen that Plotinus’ metaphysics opens the door, through its emphasis on the affinities between Intellect and the One, and through its insistence on the simultaneous capacity of the Intellect to give rise to the world of Being and to remain free of all objects, to a realization: the entire world of manifestation is none other than the self-disclosure of the One. Proclus’ metaphysics of Being, though it reiterates and formalizes the ontological principles of Platonism and the model of procession employed by Plotinus, rather emphasizes a hierarchical world: the soul visits, as it were, its source in the One. It catches a glimpse of that ultimate principle but accepts its place in the cosmic chain.

DAMASCIUS’ METAPHYSICS OF NON-BEING

It is now time to confront how the Neoplatonic tradition after Proclus engaged with the paradoxical implications of Proclus’ system, and with the paradoxes inherent in the very postulation of Being as a product of two principles: the indefinite flow of power and the fixity of that power (apeiron and peras) in the eternal self-determination of Being. For this task, we turn to the work of Damascius, the last scholarch of the school, who in his Problems and Solutions Concerning First Principles reveals a systematic tendency to criticize the developments of Proclus’ metaphysics by introducing and fundamentally elevating the prior interpretations of the influential third-century Syrian philosopher, Iamblichus, vis-à-vis scholastic questions. For example, although Damascius sympathizes with Proclus’ and Plotinus’ insistence on the transcendent simplicity of the One, he does so to the extent that he is not actually content to call the One “the One”. Instead, it has no name – perhaps it can be called the Ineffable (arrhēton).

Damascius launches his Problems and Solutions by calling into question Proclus’ derivation of all things from the One. In the rest of the work, he advances what is both a critique of Proclus’ theory of causation at the level of the Ineffable, the highest principle, as well as a positive account of the One. Therefore, Damascius, like his more recent predecessors, once more responds to what we saw was Plotinus’ initial enquiry – why does the One, which lacks all attributes, flow forth, so to speak, as “all things”? “Is the so-called One Principle of all things beyond all things or is it one among all things, as if it were the summit of those that proceed from it? And are we to say that ‘all things’ are with the [first principle], or after it and [that they proceed] from it?” (Pr. I.1.1–9).

As demonstrated in the first part of this chapter, Plotinus leaves the fecundity of the One largely unexplained – he relies on metaphors that imply the infinite generosity of the One coupled with its infinite power. Proclus, of course, assumes this much when he writes that “every manifold in some way participates [in] unity”, but has some difficulty in explaining how the One is something in which all things participate. Again, as we saw, he arrives at a compromise solution when he suggests that there are principles in the realm of the One, the primal pair consisting in limit and the unlimited, that bring about the realm of Being as their product. This solution does not satisfy Damascius, and much of the Problems and Solutions is devoted to a discussion of the One. For him, the word “One” will imply “all things”. The One includes all things by its very nature, and so there are actually three names for the One: the One (hen), the One-all (hen-panta) and the Unified hēnōmenon).

Throughout his discussion of the first principles, however, Damascius maintains a much more aporetic stance than Proclus. Even if he suggests doctrinal innovations, his very manner of couching them is more often than not obscured by what he understands as the problematic nature of metaphysical discourse proper. For example, in discussing the causality of the One, he asks:

What follows after this discussion is an inquiry into whether there is a procession from the One into its subsequents, and of what kind it is, or whether the One gives no share of itself to them. One might reasonably raise puzzles about either position. For if the One gives no share of itself to its products, how has it produced them as so unlike itself, that they enjoy nothing of its nature?

(Pr. I.99)

On the other hand, Damascius wants to claim that no such procession is possible, given that procession implies distinction (the distinction between what proceeds and what does not proceed) and therefore, there can be no procession from the One:

Every procession takes place together with distinction, whereas multiplicity is the cause of every distinction. Distinction is always the cause of multiplicity, whereas the One is before multiplicity. If the One is also before the One in the sense that the One is taken as one without [others], then a fortiori the One is before the many. Therefore the nature of the One is entirely without distinction. And therefore the One cannot proceed.

(Pr. I.100)

After posing the aporia concerning transcendence in the opening sections of the work, as well as his general criticism of Proclus’ understanding of Being as the product of the intelligible realm, Damascius launches a sustained enquiry into the meaning of Proclus’ spiritual circuit in so far as it relies on the concepts of “procession” and “reversion”, by revealing what are at least on the surface the fallacies entailed by Proclus’ solution of circular causation:

What is it we mean when we say, “remaining in the cause”? Something must be either first or third, so that it cannot be the processive if it is still that which remains. Does remaining mean that what proceeds has its origin in the cause? But this is absurd: cause must be prior; effect is subsequent. Perhaps the cause remains while the effect proceeds?

(Pr. II.117)

But now the whole idea of remaining in the cause is trivialized, and amounts to no more than the tautology that the first is not the second, and so forth. Again, Damascius critically examines the structure of procession, showing that reversion is part of a unified triad, in which the three moments act together to define the nature of a hypostasis, but at the same time, reversion is also dissolution or undoing of the very effects achieved through the process of procession. How is it possible for reversion to assume these very different functions? He also points out that “reversion” is ambiguous between something which achieves its own definition from an inchoate state, and something which returns to a higher source or to its cause.

Damascius’ innovations in the realm of metaphysics are actually implied both by Proclus’ complete theory of cyclical creativity and indeed by Plotinus earlier, as, for example, when he says at Enn. VI.5[23].7.1–2: “for we and what is ours go back to real being and ascend to that and to the first which comes from it”

The spiritual circuit, the return of all to the One and especially the soul’s special function as a conduit of this return, is the crucial premise of Neoplatonism in so far as it constitutes a religion. What, after all, is the place of the human self in this cosmic drama of the One’s radiance and of attaining to the goal of wisdom, which is to uncover a vision of the whole? The soul’s destiny is to return to the One, not just in the sense that the soul will develop wisdom or knowledge but also in the sense that the soul becomes instrumental in the completion of the spiritual circuit. Yet how the soul accomplishes this very journey is exactly the problem entailed by the system that, as it were, underwrites it. This anxiety pervades Damascius’ criticisms.

In attempting to undermine the metaphysics of Being developed by Proclus, Damascius will appear to be a David, flinging shots against the over-towering system of Proclus: he can sound even more scholastic, almost pointlessly refining the language of metaphysics in order to bring down a creative edifice that, after all, remains a celebration of the divine nature of Being, of the sanctity of the cosmos as a whole, as well as a truthful indication of where the good of the intelligent beings, inhabiting that cosmos, actually lies. All this, as we have seen, is in keeping with fundamental Platonic axioms. Yet in my view, Damascius also performs a crucial role in the tradition he inherits. We can see that he shifts the perspective of his metaphysics: he struggles to create a metaphysical discourse that accommodates, in so far as language is sufficient, the ultimate principle of reality. After all, how coherent is a metaphysical system that bases itself on the Ineffable as a first principle? Instead of creating an objective ontology, Damascius writes ever mindful of the limitations of dialectic, and of the pitfalls and snares inherent in the very structure of metaphysical discourse:

If, in speaking about [the Ineffable], we attempt the following collocations, viz. that it is Ineffable, that it does not belong to the category of all things, and that it is not apprehensible by means of intellectual knowledge, then we ought to recognize that these constitute the language of our own labors. This language is a form of hyperactivity that stops on the threshold of the mystery without conveying anything about it at all. Rather, such language announces the subjective experiences of aporia and misapprehension that arise in connection with the One, and that not even clearly but by means of hints.

(Pr. I.8.11–16)

Beyond the discourse of metaphysics lies the empty ground of wisdom, rooted in the unconditioned reality that is the One. It is for this reason, perhaps, more than any petty academic rivalries or obsessions with scholasticism that Damascius, as the last of the scholarchs, reminds us of the limitations that beset all metaphysical discourse. At the cost of originality, he shadows Proclus and attempts to undo the great edifice of the metaphysics of being, in order to return his reader to the intellect that does not grasp being. In closing his work, Damascius clarifies the relationship between individual and the first cause, the One or Good, perhaps pleading for a return to Plotinus’ metaphysics of light: “The way the individuals are contained in that nature and the way they are differentiated from it is like the light of the sun, which forever remains both in its own commonality and also is distributed individually to each being, because the sun contains a single illuminating cause of all the individual eyes” (Pr. I.96).

Contemplation, the direct self-realization of the nature of the One as permeating the ground of one’s own Intellect; the awareness of the pristine nature of wisdom that does not grasp being as something outside of itself, this is the fundamental ground that Damascius attempts to uncover beneath the overarching, byzantine structure of Proclus’ metaphysics of being. So Damascius says of contemplation, the only compelling human enterprise for him: “We attempt to look at the sun for the first time and we succeed because we are far away. But the closer we approach the less we see. And at last we see neither [sun] nor other things, since we have completely become the light itself, instead of an enlightened eye” (Pr. I.85).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

My sincerest thanks to the editors of this volume, Svetla Slaveva-Griffin and Pauliina Remes. Their vision for the volume as a whole as well as their investment in the details of each article, including my own, is commendable. I would also like to thank the careful comments of an anonymous reviewer of this chapter, whose criticisms improved the article immeasurably.

NOTES

1. Neoplatonic texts address the reader as one who earnestly strives to assimilate the truths under discussion, cf. the instructions cited in notes 2–5 below. Plato’s texts themselves share this assumption about ignorance on the part of the audience/reader: “Strange prisoners”. “They’re like us” (R. 515a.2).

2. Enn. I.6[1].8.26: ἀλλ’ οἷον μύσαντα ὄψιν ἄλ λην ἀλλάξασθαι καὶ ἀνεγεῖραι, ἣν ἔχει μὲν πᾶς, χρῶνται δὲ ὀλίγοι. All translations from the Enneads, hereinafter, are according to Armstrong (1966–88), with modifications or otherwise specified.

3. Enn. V.8[31].9.4: Ἔστω οὖν ἐν τῇ ψυχῇ φωτεινή τις φαντασία σφαίρας ἔχουσα. πάντα ἐν αὐτῇ.

4. Enn. V.3[49].17.38: Πῶς ἂν οὖν τοῦτο γένοιτο; Ἄφελε πάντα.

5. Enn. V.2[11].1.1: “The One is all things and not a single one of them; it is the principle of all things, not all things, but all things have that other kind of transcendent existence; for in a way they do occur in the One.” Also Damascius, de Principiis 1.1: “Is the so-called ‘One Principle’ of all things beyond all things or is it one among all things, as if it were the summit of those that proceed from it? And are we to say that ‘all things’ are with the [first principle], or after it and [that they proceed] from it?” All translations of de Principiis are from Ahbel-Rappe (2010). An exemplary approach to the metaphysics of Proclus via the dialectic of one and many may be found in Steel (2010).

6. Enn. IV.8[6].1.1: “Often I have woken up out of the body to my self and have entered into myself.”

7. Cf. Syrianus, in Metaph. 4.27–32: “For by the analytical method wisdom grasps the principles of being, by the divisional and definitional method the substances of all things, by the demonstrative inferring the essential properties of substances. This however is not the case with substances, which are the most simple and properly speaking intelligible, for these substances are entirely that which they are. For this reason they cannot be defined or demonstrated, but are grasped only by apprehension.”

8. Enn. VI.5[23].7.1–6: “For we and what is ours go back to real being and ascend to that and to the first which comes from it, and we think the intelligibles; we do not have images or imprints of them. But if we do not, we are the intelligibles. If then we have a part in true knowledge, we are those; we do not apprehend them as distinct within ourselves, but we are within them.”

9. Cf. Proclus, ET prop. 1: “Every multiplicity participates a Unity.” In Enn. V.1[10], Plotinus interprets the three initial hypotheses in the second half of Plato’s Parmenides as adumbrating his own metaphysical doctrine, according to which reality has different levels, which are, for Plotinus, the One, Intellect and Soul. He refers the first hypothesis (“if the one is”, Prm. 137c4) to the One beyond being, the transcendent source of all.

10. On Plotinus’ metaphysics of the dyad, see Slaveva-Griffin (2009).

11. Cf. Proclus, ET prop. 30: “If, on the other hand, it should remain only without procession, it will be indistinguishable from its cause, and will not be a new thing, which has arisen while the cause remains.”

12. Cf. Plotinus’ description of the One as (Enn. VI.8[39].16) “an eternal awakening … super-intellection” He explains that the One’s activity, its productivity, is “like being awake with nothing else to wake it”, and that “Intellect and intelligent life” “are identical with it”. Therefore, he concludes, Intellect and wisdom and life “come from it and not from another” (Enn. VI.8[38].16.35–8, trans. Dillon & Gerson).

13. As I explain in the next section, Plotinus relies heavily on the Republic’s analogy of the sun to discuss the contemplative dimensions of metaphysics: everywhere intellect is characterized by “theōrein”. Cf. Enn. V.1[10].6.28.

14. Cf. Proclus, ET prop. 75: “Every cause properly so called transcends its resultant.”

15. Proclus, ET prop. 30.25: “For if it is a new thing, it is distinct and separate; and if it is separate and the cause remains steadfast, to render this possible it must have proceeded from the cause.”

16. Cf. Damascius, Pr. I.18: “‘Nothing’ has two meanings: one is transcendent, the other is not. In fact the [word] ‘one’ also has two meanings, as the limit for example of matter and as the first, or what is before being. Therefore ‘not being’ also [has two meanings], as not even the one as limit, and as not even the first. In a similar way the unknowable and Ineffable have two meanings, as that which is not even the limit of conception, and that which is not even the first.”

17. In using the heading for this section, I owe much to Beierwaltes (1961). For Beierwaltes, light is not merely a metaphor when used to describe Intellect, but can only succeed as an image of Intellect “because there is a presence of the original in the image” (ibid.: 342, my trans.). On the activity of the One as contemplative, Emilsson (2007: 71) cites V.4[7].2.15–9: “the One is not like something senseless; all things belong to it and are in it and with it, it being completely able to discern itself. It contains life in itself and all things in itself, and its comprehension of itself is itself in a kind of self-consciousness in everlasting rest and in a manner of thinking different from the thinking of Intellect” (trans. Emilsson). Cf. also Enn. VI.7[38].39.1–4, quoted below, where Plotinus talks about the One’s “concentration” on itself.

18. Enn. V.3[49].17.30–39: “this [light] is from him and he is it; we must think that he is present when, like another god whom someone called to his house he comes and brings light to us: for if he had not come, he would not have brought the light. So the unenlightened soul does not have him as god; but when it is enlightened it has what it sought, and this is the soul’s true end, to touch that light and see it by itself, not by another light, but by the light which is also its means of seeing. It must see that light by which it is enlightened: for we do not see the sun by another light than his own.” Enn. VI.8[39].16: “an eternal awakening … super-intellection”.

19. For example, in Enn. III.8[30].9.31, Plotinus explicitly tells us that Intellect is “amphistomos” (facing in two directions); possibly he means remaining in the One as well as proceeding from the One: τὸν νοῦν οἷον εἰς τοὐπίσω ἀναχωρεῖν καὶ οἷον ἑαυτὸν ἀφέντα τοῖς εἰς ὄπισθεν αὐτοῦ ἀμφίστομον ὄντα. “Intellect approaches as it were from behind and as it were lets go of itself into what is behind it, as it faces in two directions.” Cf. Bussanich (1988) and commentary ad loc.

20. Enn. V.1[10].6.26–9: Πῶς οὖν καὶ τί δεῖ νοῆσαι περὶ ἐκεῖνο μένον; Περίλαμψιν ἐξ αὐτοῦ μέν, ἐξ αὐτοῦ δὲ μένοντος, οἷον ἡλίου τὸ περὶ αὐτὸ λαμπρὸν ὥσπερ περιθέον.

21. Plotinus continually turns to and adapts freely the language of R. 509a.3, especially emphasizing the affinity between the One and Intellect: Ὅ τι οὖν ἐγέννα, ἀγαθοῦ ἐκ δυνάμεως ἦν καὶ ἀγαθοειδὲς ἦν, καὶ αὐτὸς ἀγαθὸς ἐξ ἀγαθοειδῶν, ἀγαθὸν ποικίλον.

22. Enn. V.1[10].7.5–6: Πῶς οὖν νοῦν γεννᾷ; Ἢ ὅτι τῇ ἐπιστροφῇ πρὸς αὐτὸ ἑώρα.

23. Following Bussanich (1988: 37). Both alternatives present problems: the abrupt change of subject έώρα, if the subject is Intellect (which has not yet been created!) defies explanation. For a thorough analysis of this passage, see Atkinson (1983), A. C. Lloyd (1987) and Bussanich (1988), all of whom offer commentaries on this text.

24. Ἐνέργεια ἡ μέν ἐστι τῆς οὐσίας, ἡ δ’ ἐκ τῆς οὐσίας ἑκάστου· καὶ ἡ μὲν τῆς οὐσίας αὐτό ἐστιν ἐνέργεια ἕκαστον, ἡ δὲ ἀπ’ ἐκείνης, ἣν δεῖ παντὶ ἕπεσθαι ἐξ ἀνάγκης ἑτέραν οὖσαν αὐτοῦ.

25. Cf. A. C. Lloyd (1987: 176) who cites Enn. III.8[30].8.31–2: “Intellect is not contemplating it [the One] ‘as one.’” “[In V.3{49}.11]… Intellect tried to grasp the One as simple but found itself with something else.”

26. On Plotinus’ philosophy of the Dyad, see Slaveva-Griffin (2009). Plotinus reaches into Pythagorean conceptualization through his reading of the Philebus’ Dyad, Peras and Apeiron.

27. A. C. Lloyd (1987: 163) cites Aristotle’s theory (de An. 431b2–5): “The faculty of thinking then thinks the forms in the images, and as in the former case what is to be pursued or avoided is marked out for it, so where there is no sensation and it is engaged upon the images it is moved to pursuit or avoidance” (trans. Ross). Bussanich discuses this theory (1988: 224) and cites Enn. V.6[24].5.15: ἀγαθὸν καὶ ὡς ἀγαθὸν καὶ ἐφετὸν αὐτῷ γενόμενον νοεῖ καὶ οἷον φαντασίαν τοῦ ἀγαθοῦ λαμβάνον.

28. For Lloyd, the object of the inchoate Intellect’s vision is the image of the One; this doctrine is consistent, he maintains, with Aristotle’s psychological theory, according to which intellect can become aware of ousia via phantasia. Cf. Bussanich (1988: 231–3) for a discussion of A. C. Lloyd (1987).

29. Again, cf. Proclus, ET prop. 30: “All that is immediately produced by any principle both remains in the producing cause and proceeds from it.”

30. A. C. Lloyd (1990: 170) has argued that these phases, the mystical union with the One and the procession of the Intellect or generation of Intellect, are parallel moments in Plotinus’ metaphysics. P. Hadot (1986: 243) also assimilates the two: inchoate and hyper-noetic Intellect are the same. Bussanich (1988: 234–5) argues vigorously against this interpretation.

31. On this controversial topic, see Trouillard (1955: 46); O’Daly (1973: 164); Bussanich (1988: 233).

32. As Dillon (2003) has shown, it is conceivable that Pythagorean interpretations of this part of the Philebus, according to which the indefinite or apeiron functioned as a dyad that acted upon the One or first principle, resulting in the development and elaboration of the order of primary beings, already figured into the Early Academy. For Proclus on the Philebus, see PT III.9.

33. Being forms the apex of the intelligible triad, which is as it were composed of two elements – the limit and the unlimited – that constitute its parts; hence its equivalence to the Platonic “mixed”. Cf. ET prop. 89: “all true Being is composed of limit and infinite” and prop. 90: “prior to all that is composed of limit and infinitude there exist substantiality and independently the first Limit and the first Infinity”.

34. Following is the Greek text of the Philebus 27d.6–10, as printed in the Oxford Classical Text, with the bracketed words indicating a textual variant; some editors print the neuter form of this phrase, as opposed to the masculine gender; thus the Mixed in this line refers either to the mixed life or to the mixed qua ontological kind: Καὶ μέρος γ’αὐτὸν φήσομεν εἶναι τοῦ τρίτου οἶμαι γένους· οὐ γὰρ [ὁ] δυοῖν τινοῖν ἐστι [μικτὸς ἐκεῖνος] ἀλλὰ συμπάντων τῶν ἀπείρων ὑπὸ τοῦ πέρατος δεδεμένων, ὥστε ὀρθῶς ὁ νικηφόρος οὗτος βίος μέρος ἐκείνου γίγνοιτ’ ἄν “We will, I think, assign it to the third kind, for it is not a mixture of just two elements but of the sort where all that is unlimited is tied down by limit. It would seem right, then to make our victorious form of life part of that kind” (trans. D. Frede).

35. Van Riel (2001: 144) points out, “Plato says that the god has ‘shown’ peras and apeiron” at Phlb. 23c.9–10. Proclus substitutes the word δεῖξαι with ἐκφαίνειν.

36. PT III.9.36.17–19: Ὅσῳ δὴ τὸ ποιεῖν τοῦ ἐκφαίνειν καταδεέστερον καὶ ἡ γέννησις τῆς ἐκφάνσεως, τοσούτῳ δήπου τὸ μικτὸν ὑφειμένην ἔλαχε τὴν ἀπὸ τοῦ ἑνὸς πρόοδον τῶν δύο ἀρχῶν. “To the extent that making is inferior to manifesting and production is inferior to manifestation, by so much the mixed has received an inferior procession from the One than the Dyad.”

37. See Chlup (2012: 78–9) on the limit and unlimited as the primary fund for every existent.

38. Cf. A. C. Lloyd (1976): “The analysis of Proclus’s proof confirms on more formal grounds the fairly obvious hypothesis that the principle of the cause being greater than its effect is the result of superimposing more Platonism on a transmission theory of causation.” For Lloyd it is obvious that the transmission theory can be traced to Aristotle. He cites GA 734a30–32, so that the Form, or conformation, of B would have to be contained in A.

39. A. C. Lloyd (1990: 98) goes on to cite the example of PT V.18.283–4. The demiurge addresses the younger gods and his words are described “as the external activity of the intellect; for they ‘make the indivisible proceed to divisible existence’”.

40. On the soul’s reversion to intellect, see Chlup (2012: 86–7), quoting ET prop. 70.8–19.

41. The classic work on this is Gersh (1973); now see the excellent treatment in Chlup (2012: 62–82).

42. On the ontological boundaries of the soul in its contact with the One, see the discussion of Chlup (2012: 174–84).