Matter and evil in the Neoplatonic tradition

In the Platonic tradition, the role of matter as a possible source of evil is closely linked to earlier discussions on the subject, especially those of Plato and Aristotle.1 But there exists a fundamental difference between the Neoplatonic treatment of this subject and its Classical sources, namely, the derivative character of matter. Indeed, beginning with Plotinus – and already before him in some other traditions such as Neopythagoreanism, gnosticism and the Chaldaean Oracles2 – matter is no longer an originative principle as was the case up to the Middle Platonism of Numenius, but an entity derived from another principle. From that point on, the classic opposition between Matter and Form, more or less acute depending on the author (but sometimes harshened to a form of radical dualism, as one can observe in Plutarch or Numenius), took on a different meaning, one which neither Plato nor Aristotle could have foreseen. Indeed, in the case where matter is a produced reality, the relationship between matter and form can be either one of relative cooperation, or one of relative opposition. But when matter and form each have an independent origin, any opposition between them tends to be seriously accentuated.

Now, this type of extreme dualism, based on two autonomous and equally primordial principles, is well known to Aristotle and is in fact attributed by him to most of his predecessors (cf. Ph. I.5–6) – while he himself holds that two opposite principles must necessarily “act on a third thing different from both” (Ph. 189a25–6), since he believes that “contraries are mutually destructive” (Ph. 192a21–2) – but especially to Empedocles, who offered, according to Aristotle, the most radical version of it:

But since the contraries of the various forms of good were also perceived to be present in nature – not only order and the beautiful, but also disorder and the ugly, and bad things in greater number than good, and ignoble things than beautiful, therefore another thinker introduced friendship and strife, each of the two the cause of one of these two sets of qualities. For if we were to follow out the view of Empedocles, and interpret it according to its meaning and not to its lisping expression, we should find that friendship is the cause of good things, and strife of bad. Therefore, if we said that Empedocles in a sense both mentions, and is the first to mention, the bad and the good as principles, we should perhaps be right.

(Aristotle, Metaph. 984b32–985a9, trans. Barnes)3

To find another dualism as radical as this one in the Greek philosophical writings, one must look to much later authors connected with Middle Platonism, such as Atticus, Plutarch, Numenius, Cronius, Harpocration or Celsus.4 The most interesting text in this respect5 is probably the one we find in Plutarch’s Isis and Orisis:

Inasmuch as Nature brings, in this life of ours, many experiences in which both evil and good are commingled, or better, to put it very simply, Nature brings nothing which is not combined with something else, we may assert that it is not one keeper of two great vases who, after the manner of a barmaid, deals out to us our failures and successes in mixture, but it has come about, as the result of two opposed principles and two antagonistic forces, one of which guides us along a straight course to the right, while the other turns us aside and backward, that our life is complex, and so also is the universe; and if it is not true of the whole of it, yet it is true that this terrestrial universe, including its moon as well, is irregular and variable and subject to all manners of change. For it is the law of Nature that nothing comes into being without a cause, and if the good cannot provide a cause for evil, then it follows that Nature must have in herself the source and origin of evil, just as she contains the source and origin of good. The great majority and the wisest of men hold this opinion: they believe that there are two gods, rivals as it were, the one the Artificer of good and the other of evil. These are also those who call the better one a god (theon), and the other a daemon (daimona).

(de Isid. et Osirid. 369b1–d7, trans. Babbitt)6

As we noted, a radical dualism of this sort is by definition excluded from an integral emanative system such as the one advocated by our Neoplatonic philosophers. For them, the challenge will consist in trying to explain how evil, defect, monstrosity and irregularity can appear inside a structure emerging from, and governed by, a unique and wholly good principle. Whence comes evil, if there exists no independent principle of evil? Whence come defects, if all realities come from a unique principle which can produce only good things and which may in no way be held responsible for evils? To resolve these questions, many avenues were explored by the philosophers of antiquity. Though we cannot here analyse each of these avenues in detail, we may say that two fundamental attitudes may be drawn from these approaches, one attempting to preserve a strong dualism inside a monist context, and the other attempting to minimize as far as possible the presence of evil, and so any opposition to the Good, within the whole universe. The first option is, for the most part, the position of Plotinus, who goes so far as to conceive of a substance of evil inside the whole, which, taken globally, is still governed by the Good. The other option, although its foundations were laid by Iamblichus, is represented largely by the position of Proclus, who in fact undertook a detailed refutation of Plotinus’ stance. We will examine each of these views successively before offering our own assessment of the debate as a whole.

The model of Timaeus 50c–51b: matter as pure receptivity and impassibility

The ultimate source of Plotinus’ analysis of the role of matter in the sensible cosmos is without doubt the Timaeus, more precisely the following passage where Plato describes the nature of the receptacle (chōra) in relation to the sensible copies appearing in it:

Now the same account holds also for that nature which receives all the bodies. We must always refer to it by the same term, for it does not depart from its own character in any way. Not only does it always receive all things, it has never in any way whatever taken on any characteristics similar to any of the things that enter it. Its nature is to be available for anything to make its impression upon, and it is modified, shaped, and reshaped by the things that enter it. These are the things that make it appear different at different times. The things that enter and leave it are imitations of those things that always are, imprinted after their likeness in a marvelous way that is hard to describe. This is something we shall pursue at another time. For the moment, we need to keep in mind three types of things: that which comes to be, that in which it comes to be, and that after which the thing coming to be is modeled and which is the source of its coming to be. It is quite appropriate to compare the receiving thing to a mother, the source to a father, and the nature between them to their offspring. We also must understand that if the imprints are to be varied, with all the varieties there are to see, this thing upon which the imprints are to be formed could not be well prepared for that role if it were not itself devoid of any of those characters that it is to receive from elsewhere. For if it resembled any of the things that enter it, it could not successfully copy their opposites or things of a totally different nature whenever it were to receive them. It would be showing its own face as well. This is why the thing that is to receive in itself all the [elemental] kinds must be totally devoid of any characteristics. … In the same way, then, if the thing that is to receive repeatedly throughout its whole self the likenesses of the intelligible objects, the things which always are – if it is to do so successfully, then it ought to be devoid of any inherent characteristics of its own. This, of course, is the reason why we shouldn’t call the mother or the receptacle of what has come to be, of what is visible or perceivable in every other way, either earth or air, fire, or water, or any of their compounds or their constituents. But if we speak of it as an invisible and characterless sort of thing, one that receives all things and shares in a most perplexing way in what is intelligible, a thing extremely difficult to comprehend, we shall not be misled. And insofar as it is possible to arrive at its nature on the basis of what we’ve said so far, the most correct way to speak of it may well be this: the part of it that gets ignited appears on each occasion as fire, the dampened part as water, and parts of earth or air insofar as they receive the imitations of these.

(Ti. 50b5–51b6, trans. Zeyl)

One is struck, in this long description, by the absolute inalterability of the receptacle itself, which, on the one hand, receives everything, but remains, on the other hand, completely unaltered throughout the process; that is, it is not modified in any way by what goes in and comes out of it. The receptacle does not deviate from its own nature (Ti. 50b9) and never assumes the Form which it receives (Ti. 50b9–51a1), therefore remaining unformed (amorphon) and above all, “outside all Forms” (pantōn ektos eidōn, Ti. 50e4–5; 51a3–4). Accordingly, the receptacle remains “an invisible and characterless sort of thing” (Ti. 51a8) and the most one dare say of it is that this third kind of being, alongside the Ideas and the copies themselves, constitutes a place (chōra) and that this place is incorruptible, and consequently eternal, as its task is exclusively to “receive all things” (Ti. 52b1–2). Yet it remains itself unknown, and is only apprehensible “by a kind of bastard reasoning that does not involve sense perception” (Ti. 52b2–3).

In all treatises, Plotinus tried to adhere as closely as possible to this fundamental Platonic conception. Accordingly, matter is assigned all possible negative predicates, and is described as being sterile (agonos),7 unreceptive (adektos),8 disgracious and ugly (aischron, aischra, aischos),9 disordered (akosmetos),10 unmixed shortage (akratos elleipsis),11 unilluminated (aphōtiston, alampes),12 irrational (alogon),13 without size (amegethes),14 immeasurable (ametros),15 unmixed (amiges),16 without share in goodness (amoiros),17 unformed (amorphon, aschemosyne, ameres, aneideon),18 without colour (amydra, achrous, amydron),19 unchangeable (analloiōton),20 indestructible (anōlethros, aphthartos),21 invisible and indeterminate (aoriston/aoristia, aoraton)22 impassible (apathes/apathes/apatheia),23 infinite (apeiron/apeiria),24 unqualified (apoios/apoion),25 uncorporeal (asōmatos),26 alterity in itself and evil in itself (autoeterotes, autokakon).27

Plotinus, of course, retains the Aristotelian word “matter” (hyle), a word absent from Plato in its technical sense. Yet Plotinus’ use of this word is far removed from its original Aristotelian sense, since Plotinian matter is no more that out-of-which (ex hou) things are made (like a statue is made, say, out of wood), as it was for Aristotle, but simply the that-in-which (en hōi) the copies find themselves. Moreover, Plotinian matter is even less real than the Platonic receptacle itself, in so far as it is no longer a space or some physical extension existing prior to the arrival of the different copies, as was the case with the Platonic chōra. Rather, matter, for Plotinus, must receive not only all the qualities from the Form, but even size itself, which the Form will communicate to it upon entry. In other words, matter receives its extension from an intelligible determination, that is, the Form, so that one can say that matter in and of itself possesses no proper dimension or extension. As Plotinus himself puts it, matter is “receptive of extension” (diastematos dektike), or the “receptacle of size” (hypodoche megethous) (Enn. II.4[12].11.18–19, 37–8), but itself without size (amegethes) (Enn. II.4[12].12.23). This surprising doctrine, possibly Chrysippean in origin (SVF II.536.b), exposed in two special developments within his corpus (Enn. II.4[12].8–12; III.6[26].16–18), transforms matter into a sort of empty concept, although not a pure nothingness, which is precisely the judgement Plotinus himself attempts to counter:

So here in the material world the many forms must be in something which is one; and this is what has been given size, even if this is different from size. … So, then, matter is necessary both to quality and to size, and therefore to bodies; and it is not an empty name (kenon onoma) but it is something underlying, even if it is invisible and sizeless.

(Enn. II.4[12].12.6–24)28

In fact, to say that matter is deprived of size amounts to saying that matter is in itself in(de)finite (of no definite size), since Plotinus, influenced here by the Philebus, holds that matter per se is unlimitedness and indefiniteness (apeiron) (Enn. II.4[12].15–16), this indefiniteness having no other option than to adapt itself to the conditions imposed by what comes to it: “But matter is indefinite and not yet stable by itself, and is carried about here and there into every form, and since it is altogether tractable (euagōgos) becomes many by being brought into everything, and in this way acquires the nature of mass” (Enn. II.4[12].11.40–43). In all those contexts, Plotinus insists on the constraint imposed on matter by the Forms: “And that which makes matter large (as it seems) comes from the imaging in it of size, and that which is imagined in it is sized in this world; and the matter on which it is imagined is compelled to keep pace (anankazetai synthein) with it, and submits itself to it all together and everywhere” (Enn. III.6[26].17.31–5). And here again: “But matter, which has no resistance, for it has no activity, but is a shadow, waits to endure passively whatever that which acts upon it wishes.”29

In this context, the image of matter as a mirror might help us understand this confusing statement about the impassibility of matter. Plotinus, as we just saw, maintains that matter endures passively whatever wishes to act upon it. But in the very same treatise, he professes that matter is impassible (apathes) (Enn. III.6[26].7.41). How are we to resolve this apparent paradox? Here again, the central inspiration comes from the chōra itself which, as we just saw, never undergoes a change of condition or state (Ti. 50b9), “for while it is always receiving all things, nowhere and in no way does it assume any shape similar to any of the things that enter into it” (Ti. 50b9–51c1). In the same way, Plotinus’ matter receives everything without being affected by anything, since matter is comparable to a mirror in which the copies as reflections of the Ideas appear: “For one must not call presence or putting on shape ‘being affected’. If one said that mirrors and transparent things generally were in no way affected by the images seen in them, he would be giving not an inappropriate image. For the things in matter are images too” (Enn. III.6[26].9.14–19).

Matter, then, receives without being altered (Enn. III.6[26].10–11) by what it receives, and therefore receives in an impassive fashion or, to put it otherwise, it participates without participating (Enn. III.6[26].14.21–2), and the change one can notice in it remains in fact exterior to it (ektos, as Plato had already written), since matter remains “alone and isolated” (monon kai erēmon) (Enn. III.6[26].9.37). And of course, matter is not affected either by the change of size or volume it endorses: “But matter, all the same, keeps its own nature and makes use of this size as a kind of garment, which it put on when it ran with it as the size in its course led it along.”30

A final point to consider is that the copy and matter do not really benefit from each other in what might be termed their sort of “external exchange”. Since matter has no affinity with what comes to it, the result is that “neither does that which enters it get anything from it, nor does matter get anything from what comes into it” (Enn. III.6[26].15.10–11). It is not only impassible, but also sterile (agonos), since it does nothing beyond offering itself as the place in which everything occurs. In this way, its existence appears minimal, or even empty. To quote Armstrong’s well-known quip, matter seems not only impassible, but impossible.31

The model of Timaeus 520–530: necessity and disorder

The paradox of Plotinian matter is that while it represents extreme weakness and poverty, it is also the most belligerent opponent possible of Form. Because of its profound for-eignness, its radical impassivity and its inalterability, matter remains what it was since its origin, and escapes definitively the work of the Good. Its extreme sterility, however, does not preclude any activity on matter’s part. Indeed, Plotinian matter is surprisingly active, although this activity amounts to nothing more than the undermining of Form. In this respect, Plotinus once again aligns his position with the text of the Ti. 52e, which holds that the Nurse of Becoming, “owing to being filled with potencies that are neither similar nor balanced, in no part of herself is she equally balanced, but sways unevenly in every part, and is herself shaken by these forms and shakes them in turn as she is moved” The presence in the chōra of these dissimilar and unbalanced powers stems from the fact that the cosmos itself is the result of two orders, as indicated at Ti. 48a: “For, in truth, this Cosmos in its origin was generated as a compound, from the combination of Necessity and Reason.” However, as we know, many followers of Plato saw in this need for combination and this random cause (Ti. 48a7) the true source of evil according to Plato.32

Perfectly plastic on one hand, matter, on the other hand, is in complete opposition to the Good. It is not merely neutral but active, a principle of evil actively opposed to the Good principle, so that it can be said, as Plotinus teaches in Enn. I.8[51], that the Good and Evil are two competing principles: “the principles are double, one of evil things, one of good things”.33 How is this possible? How can one conceive of an opposition, in a single cosmos, of two substances independent of each other, as when Plotinus explains that “the substantial reality of the divine is contrary to the substantial reality of evil” (Enn. I.8[51].6.46–7)? How can there be two wholes opposed to each other, as when we read that this “whole, too, is contrary to the whole” (Enn. I.8[51].6.43–4), and how did they come to this antithetical situation? The responses of Plotinus to these different questions are exceptionally complex, and have often been misunderstood, not only by modern interpreters, but also by his immediate successors.

First, it must be understood that matter may constitute a whole, and even a very bad one, as its nature is infinite and undefined, and that it embodies in this way the native disorder. This analysis is based not only on the chōra of the Timaeus, but on the apeiron in the Philebus (24c–d). For Plotinus, matter “must be called unlimited of itself, by opposition to the forming principle; and just as the forming principle is forming principle without being anything else, so matter which is set over against the forming principle by reason of its unlimitedness must be called unlimited without being anything else” (Enn. II.4[12].15.33–7). The same teaching is to be found later in Enn. I.8[51]: “Indefiniteness and unmeasuredness and all the other characteristics which the nature of evil has are contrary to definition and measure and the other characteristics present in the divine nature” (Enn. I.8[51].6.41–3). However, it is known that this indefinite nature is intrinsically evil, because any improvement would destroy its condition: “For if it really participated and was really altered by the good it would not be evil by nature” (Enn. III.6[26].11.41–3).

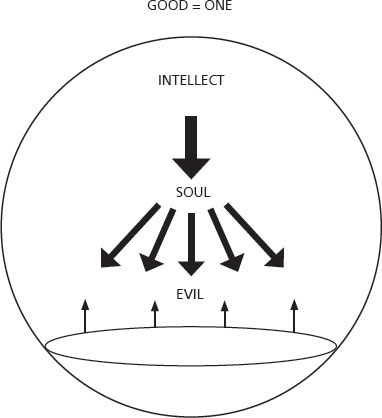

Second, one might ask how there could be two wholes opposed to one another. The response of Plotinus is to place one of the two wholes in internal opposition to the other whole. The whole of evil is opposed, but from inside, to the whole of the Good which encompasses it externally. Evil-matter is thus a heterogeneous whole within Being itself. This is shown schematically in Figure 15.1.

By means of this approach, Plotinus retains the benefits of mixed dualism (evil does not come from the first principle, but exclusively from the second; evil manifested as real force, although it remains less than the force of the Good; each individual has the responsibility, through the exercise of the virtues, to get closer to the first principle and flee from the second) and monism, since the whole remains overall a good whole, in spite of the presence in it of a bad element, both limited and impregnable.

Figure 15.1 Structure of evil-matter.

The evil cannot be totally outside of being (because there is no such outside), but it cannot be inside either, since it is radically opposed to being: so it is both inside and outside, inside but as an outsider (cf. Enn. III.6[26].14.18–25). This is why Plotinus is able to compare the evil with a prisoner bound with golden shackles. Evil is always present, threatening and real, but it is still contained within the limits of the Good: “But because of the power and nature of good, evil is not only evil; since it must necessarily appear, it is bound in a sort of beautiful fetters, as some prisoners are in chains of gold, and hidden by them, so that though it exists it may not be seen by the gods” (Enn. I.8[51].15.23–5).

Placed between the two poles, each individual is therefore tasked, through philosophical activity, to break free of the attraction exercised by evil and go back to his homeland. The recognition of the presence of primary evil in matter is not an encouragement to inaction or pessimism, but an appeal to courage and reflection. Since each individual does not himself embody primary evil, and since primary evil also does not exist beyond the material level, optimism remains possible for everyone, providing one does one’s best to escape the worst. Inherently bad action is therefore not directly human, but the initiative of matter itself, the first unmixed Evil (to prōton kai akraton kakon, Enn. I.8[51].12.5), which is Evil per se (autokakon, Enn. I.8[51].8.42, 13.9), and which Plotinus somehow personifies. This personification of the role of matter in Plotinus’ analysis, we cannot fail to notice, represents the most crucial difference with the description of the receptacle in the Timaeus, because Plotinian matter is not only a blind corrupting factor, as in Plato, but something which presents itself as intentionally bad. Of the chōra, one could say (even though Plato himself does not say so) that it is bad as one says that “the weather is bad”, but not in the sense that one “acts badly” or “pursues bad ends”. But of the Plotinian matter, one is no longer so sure, as the description of the battle between Soul and matter here below in Enn. I.8[51] reflects:

There is matter in reality and there is soul in reality, and one single place for both of them. … But there are many powers of soul, and it has a beginning, a middle and an end; and matter is there and begs it and, we may say, bothers it and wants (thelei) to come right inside. … This is the fall of soul, to come in this way to matter and to become weak, because all its powers do not come in action; matter hinders them from coming by occupying the place which soul holds and producing a kind of cramped condition, and making evil what it has got hold of by a sort of theft – until soul manages to escape back to its higher state. So matter is the cause of the soul’s weakness and vice: it is then itself evil before soul and is primary evil.

(Enn. I.8[51].14.27–51)

In this description, aside from the explicit designation of matter as something evil per se and principle of all evils, several verbs reflect matter’s autonomous action against the Soul. Both of these ideas are clearly absent from the vocabulary of the Timaeus.

Finally, how have these two wholes come to this reciprocal situation? Plotinus rejects the original dualism and he categorically refuses the possibility that evil comes from divine realities above. Hence, the only solution for him was to make the primary evil responsible for its own emergence. The primary Good does not yield the primary Evil. Rather, among the primitive otherness, which emanates from the first Good, there is something which has escaped from above by itself, as if of its own initiative (see Enn. VI.1[42].1), and has pursued its flight towards the lower world. Facing this escape and this flight, the role of the Soul has been to catch up with the infinite matter and to envelop it from the exterior in order to stop its flight. From then on, situated in the very depths of the world, the Evil-infinite-matter is the counter-principle, admittedly with limited power, but eternally acting, and to which the different powers of the soul will confront each other in their descents. Briefly outlined, this is the principle of Plotinus’ solution. A detailed analysis of several passages relating to this emergence of matter allows for a reconstruction of Plotinus’ solution to the problem of evil.34

Assessment of Plotinus’ position on evil

The benefit of Plotinus’ position on evil is that it enables an account of a genuine opposition between the beneficial and harmful acts in the sensible world. It is indeed possible in certain cases to let oneself be overcome by the corporeal passions, which take root in the blind and brutal force of matter. Moreover, it is because we are beings composed of matter and Form that vice is possible. As Plotinus mentions, the Idea of the axe does not cut, it is only the physical axe that cuts (see Enn. I.8[51].8.11–14). The will to possess in excess, to dominate and to subjugate finds its source in a blind, savage and insatiable want. In certain cases, the soul can let itself be governed by its inferior parts, by the passions, which rise unordered out of the material components of the body. This possibility depends on an exterior force which comes from below and which is completely real, as Plato’s Phaedo had already suggested when evoking the body.35 In this sense the evil-matter is not simply a lack or a privation of something: it is a positive force, which, in certain cases, can become dominant and pervasive. If the inferior can at times prevail over the superior, it is because the inferior, dynamically speaking, disposes of a power that is not only real – and that is thus not simply a lack or an absence – but at times superior to what is axiologically superior to it. It is in this sense that Plotinus can speak of a struggle between two antithetic principles, even if it is evident that the principle of evils exerts a power on the whole inferior to that of the principle of goods.

There is, however, a flaw, or weakness, in Plotinus’ position, which lies in his absolutization of the role of matter as source of evil. Indeed, were we to take literally the assertion according to which “matter is the cause of the soul’s weakness and vice: it is then itself evil before soul and is primary evil” (Enn. I.8[51].14.49–51), then not only could we no longer differentiate one soul from another, but there would also no longer be any point in advocating virtue and practising of philosophy. For if matter is the exclusive cause not only of physical, but also of psychic flaws, such as weaknesses of the soul, then there no longer exists a differential factor between the souls, and we would fall into a sort of absolute materialism.

Yet I do not believe that this reflects the definitive position of Plotinus on the subject. Certainly, he insists on not reproducing the gnostic pattern according to which the fall of the soul in the sensible world is fundamentally due to a flaw within the soul itself (Enn. II.9[33].12–14). The truth, for Plotinus, is that radical evil exists (it is the infinite-matter), that the flaws exist before us (pro hemōn tauta) (Enn. I.8[51].5.27–8) in matter, and that consequently, the lack of good (elleipsis tou agathou), which arises in the soul, cannot be the first evil. Otherwise, he thinks, “the nature of evil will no longer be in matter but prior to it” (Enn. I.8[51].5.4–5), which would place its origin squarely with the primary divine principles, including souls, a gnostic thesis which Plotinus wishes to avoid at all costs.36 That being said, Plotinus’ fundamental conviction is that despite the determining influence of the matter, “there is an ‘escape from the evils of soul’ for those who are capable of it, though not all men are” (Enn. I.8[51].5.29–30).

MATTER AND EVIL IN PROCLUS

It is well known that the Plotinian views on matter and evil have, since late antiquity, been subject to numerous criticisms. Moreover, even Plotinus’ immediate Neoplatonic successors did not follow him on this subject. Plotinus himself is partly to blame for this, as a few of his theses were articulated in a manner that could lead to confusion. Such is the case when he speaks of an opposition between the two principles of matter and the Good, as if they were two equivalent poles.

Proclus reproaches him for this in the de Malorum Subsistentia 31:

But if matter is evil, we must choose between two alternatives: either to make the good the cause of evil, or to posit two principles of beings. … Now, if matter stems from a principle, then matter itself receives its procession into being from the good [and cannot, accordingly, be evil per se]. If, on the other hand, matter is a principle, then we must posit two principles of beings which oppose each other, viz. the primary good and the primary evil. But that is impossible. For there can be no two firsts.

(DMS 31.6–14, trans. Opsomer & Steel)

Proclus offers the same criticism regarding the professedly absolute action of the matter on the soul: “If souls are drawn by themselves, evil for them will consist in an impulse towards the inferior and the desire for it, and not in matter. … If, on the other hand, souls are drawn by matter …, where is their self-motion and ability to choose?” (DMS 33.15–25). The problem to which Proclus alludes here is real, even if, as we have argued above, it is possible to find in Plotinus at least a partial solution to this difficulty.

Admittedly, Proclus concedes that it is indeed here below, where matter is to be found, that evil appears (DMS 51.40–46), and where individual fallen souls, endowed with material bodies, are to be found (DMS 23–4, 28). It does not follow, however, that this is the cause, and even less the sole cause, of the disorder with which we are constantly confronted here below, as this finds its origin not at the level of the receptacle itself, as Plotinus falsely believes when reading Ti. 30a2–6, but already in the unlimitedness created by God, as shown by the Phlb. 26c4–27c1. In short, according to Proclus, there is no reason to make matter, which derives from a good principle, evil in itself by giving it the status of principle.37

In Proclus’ eyes, the only judicious solution is to posit that there is no unique evil in itself. Instead, there are various evils that afflict equally various beings, evils, which are like accidents, deviations of realities that are a priori good. The technical term to denote such an accident is parypostasis, which can be translated as an adventitious existence: “For the form of evils, their nature, is a kind of defect, an indeterminateness and a privation (ellipsis, aoristia, sterēsis); their mode of existence (hypostasis) is, as it is usually said, more like a kind of adventitious existence (parypostasis)” (DMS 49.7–10, slightly modified).

Such an explanation, however, gives rise to a grave difficulty for Proclus, namely that of explaining how what is simply a lack or a privation, and thus inferior to that which it opposes, can have the strength to modify or contaminate a being that is superior to it. In other words, what in his system can play a role comparable to that of the recalcitrant receptacle of the Timaeus, or of the malignant matter of Plotinus? Is evil really only an absence, a lack, or a progressive exhaustion of the Good, incapable of retaliation? The dualism that opposes evil-matter to the Good which we have seen in Plotinus will no doubt be suppressed by Proclus in favour of a new form of dualism, a dualism of privations. In this new dualism, we suddenly find opposed, on the one hand, privations which are only privation, that is to say pure absences, or lacks, and on the other hand, privations which, curiously, may only be described as incomplete privations. These incomplete privations are not “altogether impotent and inefficacious” (impotentes omnino et inefficaces), but reveal themselves capable of opposing the Good. These special privations are in fact forms of negative possessions, which are capable not only of turning on their positive counterparts, but also of prevailing over them:

Evil is indeed privation, though not a complete privation. For being coexistent with the very disposition of which it is privation, it not only weakens this disposition by its presence (illum quidem debilem facit ipsius presentia), but also derives power and form from it (ipsum autem assumit38 potentiam et speciem ab illo). Hence, whereas privations of forms, being complete privations, are mere absences of dispositions, and do not actively oppose them, privations of goods actively oppose (adversantur; machontai [Isaac]) the corresponding dispositions and are somehow contrary to them. For they are not altogether impotent and inefficacious; no, they are both coexistent with the powers of their dispositions, and, as it were, led by them to form and activity.

(DMS 52.2–10)

Here, Proclus seems caught in a sort of contradiction, inasmuch as this privation of the second type (i.e. the privation that is not purely privation) must already be in possession of a certain power to be capable of weakening its positive counterpart, of fighting against it, and of deriving its strength from it; and yet, at the same time, it must not itself already possess any strength, if it is indeed true that its strength comes entirely from its adversary. This non-privative privation must then at once possess, and not possess, the strength with which we credit it. The situation is comparable to that which one can notice in the argument causa sui, which also rests upon an initial contradiction. Indeed, in order to cause oneself, it is necessary to both not be, so that one requires a cause, and yet to be already, so that one is capable of causing oneself. Hence, the same thing must at the same time, and from the same point of view, be and not be, which is evidently a contradiction. Likewise, in Proclus, if evil is de facto “unwilled, weak and inefficacious (involitum et debile et inefficax)” (DMS 54.7), it is hard to conceive by what means it could, as Proclus claims, not only borrow its strength from its adversary against its will, but also succeed in defeating it! This is what seems to occur when he writes: “Likewise in souls, evil, when it vanquishes good, uses the power of the latter on behalf of itself. That is, it uses the power of reason and its inventions on behalf of its desires” (DMS 53.14–16; see also 7.35–42, 38.13–25). This autonomous power of retaliation, or even of quasi-rational calculation, which is suddenly granted to evil by Proclus, echoes, in a certain way, the attitude of Plotinus, which seems, at first glance, equally contradictory. Plotinus, on the one hand, presented matter as a pure principle of receptivity, denuded of power, and on the other hand, suddenly granted matter a capacity for action contra Form and what comes close to resembling a “will” to fight against it. The language employed here by Proclus indeed is highly reminiscent of that of Plotinus. According to Proclus, this special privation “weakens the disposition by its presence” (illum quidem debilem facit ipsius presentia, DMS 52.5–6), which is exactly what Plotinus says about its active principle of evil: “matter is present, begs it and bothers it”; “matter darkens the illumination, the light from that source, by mixture with itself, and weakens it”; “matter’s presence has given soul the occasion of coming to birth” (Enn. I.8[51].14.35–6, 40–42, 53–4).

This ultimately contradictory approach we find in both authors seems to be not the sign of a simple inconsistency in their analyses, but the reflection of a sort of antithesis inherent to any study of the concept of evil. On the one hand, the Good cannot be the cause of evil, and Plotinus and Proclus both agree with Plato on this fundamental point. On the other hand, the efficiency, and even the refinement, of the means we see employed in certain bad actions compels us to abandon the conception of evil understood as simply a digression from, or an attenuation of, the Good. For how else shall we understand the relative autonomy of evil and its, at times, surprising capacity for action? Yet, to speak of Evil as simply a pure contrary, as if it occupied a rank equal to that of the Good, is evidently unjustified, and Proclus was, in this regard, right to criticize Plotinus’ formulations. Evil is not a contrary, but rather, a subcontrary. Consequently it can, according to Proclus himself, possess a certain power: it is not simply privation and lack. This, of course, gives rise to the question of whence evil derives its power and how it comes to acquire it thence. Is it that power is somehow bestowed upon it (although it is impossible that the Good itself should positively empower evil), or because evil siphons off the power of its host? But if the latter is the case, how does evil manage to do this if it has no power of its own?

In sum, we note that Plotinus and Proclus do not end up with widely divergent results, despite the considerable differences in their respective approaches. Admittedly, Plotinus roots all the particular evils in a unique primary evil, while Proclus objects to the existence of any positive evil, for which he substitutes singular evils understood as defects or absences. But even Proclus cannot hold himself to such a lifeless representation of evil.39 This explains the sudden emergence in Proclus’ writings of these privations of a new kind, in truth harmful powers, stemming from who knows where, but suddenly capable of real obstructions and even of partial victories.

In short, Plotinus and Proclus both undertake, in their own way, a task that is as necessary as it is problematic,40 namely to account for tensions and oppositions which arise in the sensible, while at the same time trying to preserve the innocence of the gods, and the idea of the fundamental goodness of the whole.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I should like to thank Simon Fortier and Svetla Slaveva-Griffin for their help in the translation and revision of this essay.

NOTES

1. For other contemporary perspectives on Plotinus’ theory of material evil, see Corrigan (1996a), O’Brien (1999), D. O’Meara (2005), Schäfer (2002). For further information concerning our own interpretation of this theory, see Narbonne (2006, 2007). For other perspectives on Proclus and the relationship of his theory of evil to that of Plotinus, see Opsomer (2001, 2007), Phillips (2007), Fortier (2008), Skliris (2008).

2. This might be the case of Moderatus who, according to Porphyry’s Περὶ ὕλης, as reported by Simplicius (in Ph. 230.34–231.24 = frag. 236 [Smith]); a good account of the issues regarding this text is found in Dōrrie & Baltes (1987–2008: vol. 4, sections 4, 122, 176–8, 477–85), would also have taught that matter is both evil and derivative at the same time, as well as for the Chaldaean Oracles (frag. 34, 88 [des Places]; cf. Psellus, Hypotyp. 27, p. 75.34 [Kroll]).

3. Greek of the italicized sections in order of appearance in the passage: τὴν μὲν φιλίαν αἰτίαν οὖσαν τῶν ἀγαθῶν τὸ δὲ νεῖκος τῶν κακῶν and τὸ κακὸν καὶ τὸ ἀγαθὸν ἀρχάς. See also Metaph. 1075b1–7.

4. For Atticus, cf. Proclus, in Ti. I.391.10 [Diehl]; for Numenius, frag. 52 [des Places]; for Numenius, Cronius and Harpocration, cf. Iamblichus, de An. 375.6–15 [Wachsmuth & Hense]; for Celsus, cf. Origen, Cels. 4.65; 8.55 [Bader].

5. Owing to our uncertainty concerning the date of the text and its fidelity to Numenius himself, one can draw no definite conclusion from Calcidius’ in Ti. (c.295–9), which lend to Numenius, as an heir of Pythagoras, a very malicious view of matter and of its role in the constitution of the world. On this, see Dillon (1994: 156–7).

6. Greek of the italicized sections in order of appearance in the passage: ἀλλ᾿ ἀπὸ δυεῖν ἐναντίων ἀρχῶν καὶ δυεῖν ἀντιπάλων δυνάμεων; δεῖ γένεσιν ἰδίαν καὶ ἀρχὴν ὥσπερ ἀγαθοῦ καὶ κακοῦ τὴν φύσιν ἔχειν; and τὸν μὲν ἀγαθῶν, τὸν δὲ φαύλων δημιουργόν.

7. Enn. III.6[26].19.25.

8. Enn. III.6[26].13.25.

9. Enn. II.4[12].16.24; III.6[26].11.27; I.8[51].5.23; 9.12–13.

10. Enn. IV.3[27].9.17.

11. Enn. I.8[51].4.24.

12. Enn. II.4[12].5.35; 10.19.

13. Enn. VI.6[34].11.32; VI.3[44].7.8.

14. Enn. II.4[12].10.1, 11.4, 13, 12.23.

15. Enn. I.8[51].3.25–9, 38, 4.27.

16. Enn. III.6[26].15.9.

17. Enn. I.8[51].4.22.

18. Enn. II.4[12].2.3–4, 10.18, 23; II.4[25].4.12; III.6[26].7.28–9; I.8[51].3.14; 8.21.

19. Enn. II.4[12].10.27, 12.29; II.5[25].5.21.

20. Enn. III.6[26].10.26–7.

21. Enn. II.5[25].5.34; III.6[26].10.11.

22. Enn. II.4[12].2.4, 10.14, 11.37, 12.23, passim; III.6[26].7.14.

23. Enn. III.6[26].6.7, 7.3, 41, 12.26, etc.

24. Enn. II.4[12].7.16, 17, 15.4; III.6[26].7.8; I.8[51].6.42.

25. Enn. II.4[12].7.11, 8.1–2, 10.2, 13.7; I.8[51].10.1.

26. Enn. II.4[12].9.5; III.6[26].6.3.

27. Enn. II.4[12].13.18; I.8[51].8.42;13.9.

28. Hereinafter the translation of the Enneads is according to Armstrong (1966–88).

29. Enn. III.6[26].18.28–30: ἀναμένει παθεῖν ὅ τι ἂν ἐθέλῃ τὸ ποιῆσον.

30. Enn. III.6[26].18.19–21. This passage refers to the peculiar Plotinian thesis according to which matter adopts the volume, which Form imposes on it as it descends. For further discussion, see Narbonne (1993: 224–60), Brisson (2000).

31. Armstrong (1966–88: vol. 3, 207): “Some readers may feel, by the time they reach the end of the treatise, that Plotinus has made matter not only impassible but impossible.”

32. Cf. Festugière (1986: xiv): “d’Albinus à Numénius, de Plotin à Porphyre, c’est quasi un dogme reçu que la matière est agitée de mouvements désordonnés avant l’intervention du Démiurge et que, par suite, l’origine du mal est dans la matière comme telle.”

33. Enn. I.8[51].6.33–4: ἀρχαὶ γὰρ ἄμφω, ἡ μὲν κακῶν, ἡ δὲ ἀγαθῶν.

34. Enn. II.4[12].15; II.5[25].4, 5; III.6[26].7, 13; VI.6[34].1–3; IV.3[27].7. For an analysis, see Narbonne (2011: 11–54).

35. Plato, Phd. 66c: “Because the wars, the discords, the battles, to elicit them there is nothing else than the body and its covetousness.”

36. Enn. II.9[33].13.27–9: “one must not consider evil as nothing else than a falling short in wisdom, and a lesser good always diminishing”.

37. On this point, Simplicius based himself on and developed Proclus’ position, CAG volume 8, part 5, pp. 109, 5–20: “But surely, Plotinus says, not-substance is in general opposed to substance, and the nature of evil is contrary to the nature of good, and the principle of the worse things to the principle of the better ones. These are to be divided thus: if not-being, which we oppose to being as its contrary, does not subsist anywhere in any way, then it will not have any relation to anything else, given that it is nothing. If, on the other hand, it exists as a determinate being, then it is wrongly said to be cut off in all respects from that which is, since it participates in it (sc. in that which is). But if they i.e. being and not-being are separate as two substances, they will have being itself as one. If, however, they are separately transcendent (exeir-emenai khoristos) because of an eminent otherness (ekbebekuian heteroteta), i.e. the Form of Otherness, then they will not share the relation of contraries since they have nothing in common with one another. And if, as is usually said, not being is produced out of being, just as the sensible is produced from the intelligible and the material from the divine as if the ultimate were produced from the first, how can it sc. non-being enjoy contrariety with it sc. being, in the sense of being in all respects separated from it, given that it sc. non-being has its entire existence from it i.e. being? How will not being, which has no ratio of either comparison or opposition towards being, but falls away to extremity as nothing, be contrary to it as to the very cause that produced it, a contrariety which causes it to be equal to that which was supposed to beits contrary?” (trans. de Haas & Fleet).

38. In the Greek text reconstituted by Isaac Sebastocrator (cf. Procli Diadochi Tria Opuscula [Boese 1960]), the Greek term is προσλαμβάνει. This term, which might also be rendered as taking to oneself or attracting to oneself, is indeed a very forceful way to describe the counteraction of this special privation!

39. One can also sense this fundamental difficulty in the secondary literature, as, for example, in Steel’s (1998) treatment of this problem, where he states at one point that in “Proclus’ elaboration of the doctrine [of evil] all dualistic explanations are completely eliminated” (p. 83) and closes his analysis by saying that, owing precisely to this special privation, “evil and good are in fact two opposite powers – and here lies the truth of the dualistic position – the one set in action against the other” (p. 101).

40. I therefore largely agree with Phillips’ following conclusion (2007: 267): “The great Neoplatonist project in formulating their doctrines of evil, to affirm the existence of evil while also placing it squarely within God’s providential control of the cosmos, and achieving both of these aims while still removing God from any and all responsibility for evil’s existence, does take a radically different course after Plotinus’ doctrine, but nonetheless is betrayed by essentially the same difficulties throughout. To be sure, Proclus refines some of the rougher edges on Plotinus’ doctrine, yet is for all that none the more successful finally in reconciling these two perhaps irreconcilable concepts.” Proclus is even less successful when one takes seriously into account, as we have attempted to do here (in so far as we are aware, for the first time), the curious double concept of privation that he surreptitiously introduces as a substitute for Plotinus’ analysis.