Jungle Cat

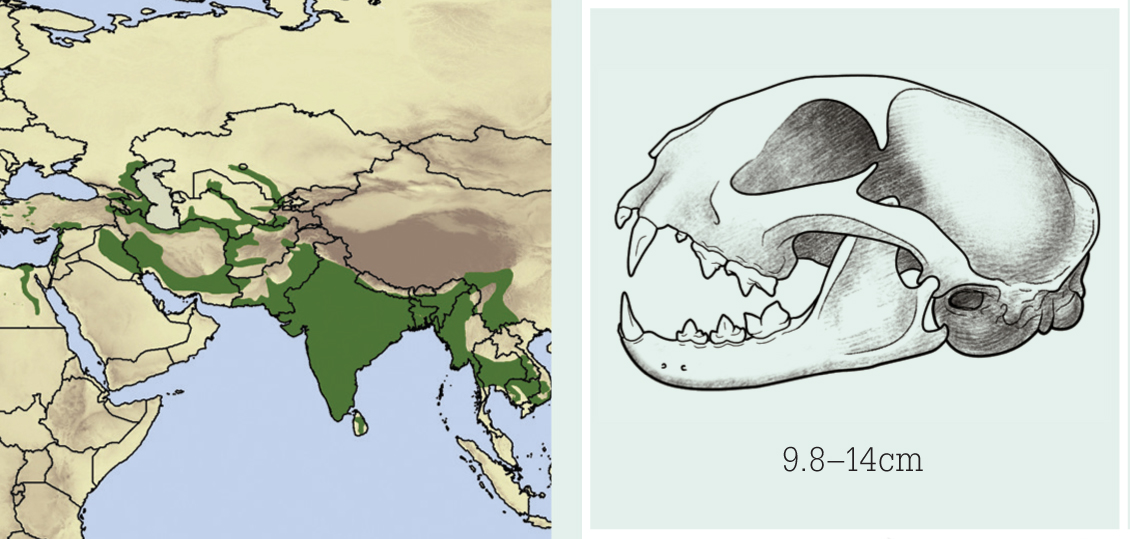

Felis chaus (Schreber, 1777)

Swamp Cat, Reed Cat

IUCN RED LIST (2008): Least Concern

IUCN RED LIST (2008): Least Concern

Head-body length ♀ 56 −85cm, ♂ 65−94cm

Tail 20−31cm

Weight ♀ 2.6−9.0kg, ♂ 5.0−12.2kg

Taxonomy and phylogeny

The Jungle Cat was once thought to be closely related to the lynxes due to superficial physical similarities, but there is no dispute that it belongs in the Felis lineage. It is thought to have diverged early in the lineage over three million years ago and is perhaps most closely related to the Black-footed Cat, though the genetic data are poor. Up to six subspecies have been described based largely on superficial differences, especially in pelage, which varies within and between populations. Most subspecies are unlikely to be valid and a modern molecular analysis of subspeciation is overdue. Domestic cats in rural areas, for example, in India and Indochina, often strongly resemble Jungle Cats, raising the possibility of widespread hybridisation (which is known from captivity). There is at least one record from India of a wild male Jungle Cat fathering kittens to a female domestic cat.

Description

The Jungle Cat is the largest of the Felis cats, with a tall, slender build, long legs and a fairly short, banded tail measuring around a third of the body length. Jungle Cats in the west and north of the range are believed to be the largest – based on a few specimens, Jungle Cats in Israel are 43 per cent heavier than those from India. The Jungle Cat’s head is relatively compact with large, triangular ears topped with a short, sometimes indistinct dark tuft; the tuft is usually obvious in kittens. Jungle Cats are uniformly coloured, typically light to dark tawny with greyish, gold or rusty tones. The body is faintly marked with indistinct stippling or spots that are entirely absent in some individuals. The lower limbs and tail are more distinctly marked with dark blotches and banding. Young kittens are often more strongly marked, with distinct blackish dabs covering the body at birth that fade rapidly. The Jungle Cat’s face is lightly marked with indistinct cheek and forehead stripes and, typically, a distinctive, bright white muzzle and chin. Individuals in temperate regions are often more richly coloured and more heavily marked; summer coats are highly variable with rich orange to coffee-brown tones while silver-grey winter coats are recorded in the extreme north of the range. Melanistic individuals are reported from India and Pakistan.

Similar species The Jungle Cat’s tall, leggy build and short tail resembles the Caracal, which is sympatric from India to Turkey; Caracals have very distinct long ear tufts and lack the leg and tail markings of Jungle Cats. Young Jungle Cats are easily mistaken for Wildcats or feral domestic cats. The Jungle Cat’s white muzzle is usually distinctive.

Distribution and habitat

The Jungle Cat has an extensive but patchy range from Vietnam and southern China to western Turkey and Egypt. The species’ stronghold is South Asia where it occurs throughout India, Bangladesh, much of Sri Lanka and through the Himalayan foothills from Pakistan to Burma. In Indochina it occurs from southern China to southern Thailand and Cambodia, with large gaps in between where it has been extirpated, is very rare or simply unknown. It occurs patchily in south-western and central Asia from Turkey to southern Kazakhstan, western Afghanistan and southern Iran. In Africa, the Jungle Cat is restricted to Egypt on the Mediterranean coast, along the Nile River Valley from the delta to Aswan, and in a scattering of oases west of the Nile.

Despite its name, the Jungle Cat avoids dense, forested habitats and is probably entirely absent from closed canopy rainforest. The species’ alternative names, Swamp Cat and Reed Cat, are more appropriate as it strongly prefers well-watered and dense reedbeds, grassland and scrubland associated with swamps, wetlands, marshes and coasts. They occur in oases and river valleys in arid habitats, for example in Egypt and southern Iran, and they inhabit cleared areas and grassland or scrub patches in moist forest. In Indochina, the species mainly inhabits deciduous woodland and open forest with rivers, floodplains and other scattered water sources. The Jungle Cat tolerates converted landscapes with water, cover and prey. They can be found in close association with people in agricultural habitats that foster dense rodent populations, for example in sugarcane fields, rice paddies and irrigated pastures. They also occur around aquaculture ponds, and in various open forest plantations, especially those with irrigation canals. The Jungle Cat occurs from sea level to 2,400m in the Himalayan foothills.

A large male Jungle Cat showing the species’ characteristic leggy build and short, banded tail. Males are taller at the shoulder and more heavily built than females.

Although often confused with feral domestic cats, this young Jungle Cat already shows the species’ characteristic enlarged ears and pale lower face.

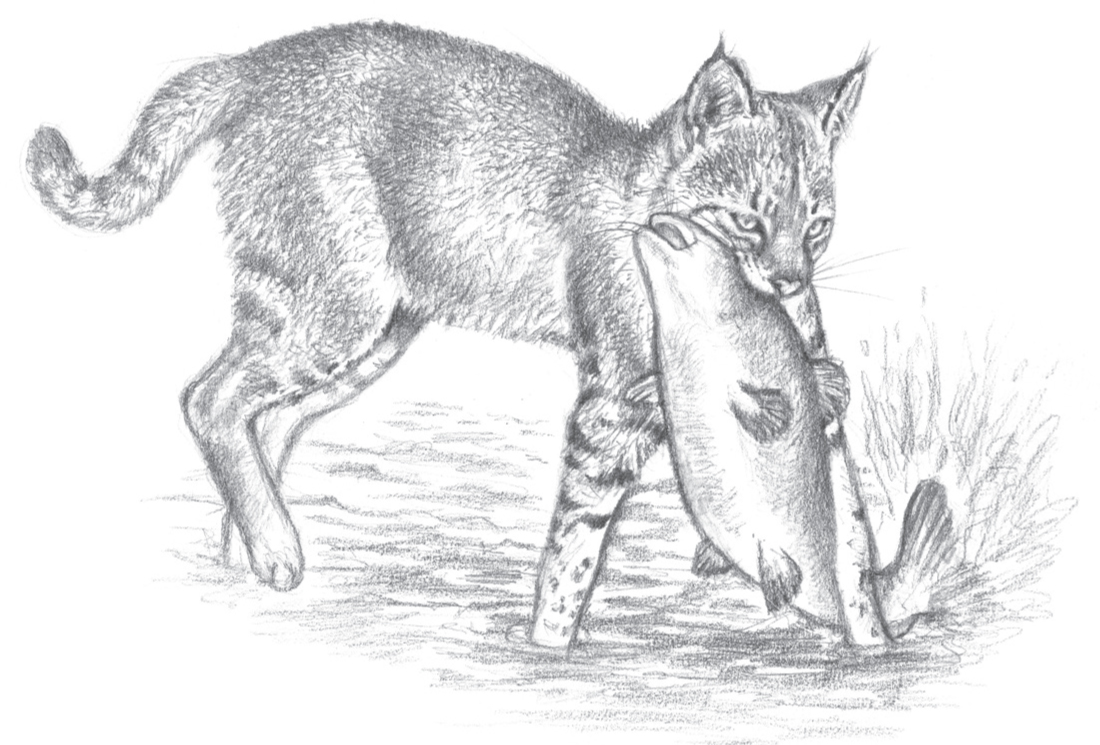

Jungle cats are very at home in water. They swim powerfully and hunt in the shallows for aquatic prey including a wide variety of fish.

Feeding ecology

The Jungle Cat feeds primarily on small mammals weighing less than 1kg, mainly mice, rats, gerbils, jirds, jerboas, voles, ground squirrels, moles and shrews, as well as Muskrats (weighing up to 2kg; introduced in parts of the range) and hares. A single Jungle Cat is estimated to eat 1,095−1,825 small rodents per year in semi-arid western India (Sariska Tiger Reserve). Jungle Cats are relatively powerfully built and occasionally take larger mammals including Coypu (weighing 5−9kg), though a large adult Coypu was successfully observed to repel an attack in Russia (the age and size of the Jungle Cat was not reported). Jungle Cats occasionally take the neonates of gazelles and Chital, and an adult cat killed captive subadult Mountain Gazelles held in large pens. Wild Boar piglets are reported as prey from the western shore of the Caspian Sea, though these were possibly scavenged; only unaccompanied, very young juveniles would be vulnerable. Birds are the second most important prey category including small species (especially grassland sparrows and larks), waterfowl, francolins, pheasants, peafowl, jungle fowl and bustards. Jungle Cats in Uzbekistan are recorded taking Western Marsh Harriers. They also eat reptiles, amphibians and a wide variety of fish. Tajikistan cats are recorded to have eaten large quantities of Russian Silverberry fruits during a lean winter. Jungle Cats prey on domestic poultry and are sometimes blamed for killing small stock; this is possible, though the records are equivocal.

The Jungle Cat forages mainly on the ground in dense cover, often along the water’s edge or among inundated vegetation. It is an excellent swimmer that crosses long stretches of open water to small islands and reedbeds, and it actively takes fish and waterfowl in the water. They are reported to excavate Muskrats from their small ‘push-ups’ (similar to beaver lodges). Foraging is thought to be cathemeral with a high degree of crepuscular and diurnal activity in sites that are well protected from people. The Jungle Cat readily scavenges, including removing animals from human traps and eating from the kills of other carnivores such as Golden Jackal, Grey Wolf, Asiatic Lion and Tiger.

Social and spatial behaviour

The Jungle Cat is very poorly known. There are no studies based on telemetry or long-term observation but limited information indicates it follows a characteristic felid socio-spatial system. Adults are solitary, and typical feline scent-marking and vocalisation suggest the maintenance of exclusive core areas. Based on incidental observations in Israel, male home ranges overlap several smaller ranges of females. There are no rigorous density estimates but they are locally common in suitable habitat in South Asia.

Reproduction and demography

This is poorly known from the wild. The species is thought to breed seasonally, which is credible for parts of the range with climatic extremes, for example Egypt, the Middle East and the extreme north of the range (Kazakhstan through southern Russia) from where most observations exist. Records of mating from these areas occur mostly in November–February and kittens are born December–June. Gestation in captivity is 63−66 days. Litters are usually two to three kittens, exceptionally up to six. Kittens are independent at eight to nine months old. Sexual maturity in captives occurs at 11 months (females) and 12−18 months (males).

Mortality There are few records of natural mortality but they are presumably killed occasionally by larger carnivores; Golden Jackals occur at high densities in much of their range and may be a threat to kittens. A dead Jungle Cat in Pakistan was found entwined with a large dead Indian Cobra, with evidence of a prolonged struggle. Humans and dogs frequently kill kill them in anthropogenic landscapes.

Lifespan Unknown in the wild and up to 20 years in captivity.

A Female Jungle Cat and her three kittens, Khijadiya Bird Sanctuary, Gujarat, India. Khijadiya is one of the few sites where it is possible to view wild Jungle Cats for extended periods.

STATUS AND THREATS

The Jungle Cat is widespread and is able to tolerate agricultural and settled landscapes where it is probably the most common felid in some regions, particularly in rural areas of South Asia. It is uncommon to very rare in Indochina, south-western Asia and central Asia. It was formerly common in its Egyptian range, though its status there is now uncertain. Despite its ability to live close to people, the species is threatened by the rapid conversion of wetland habitats for human settlement and agriculture. In Indochina and much of South Asia, this is compounded by very widespread, unselective snaring to which the Jungle Cat is particularly vulnerable given its preference for open habitats that are very accessible to people. In the northern parts of the range, it is trapped for fur and it is hunted heavily around Coypu and Muskrat fur-farms in the former USSR republics. They are persecuted for poultry-raiding and have declined in agricultural areas where unselective trapping and poisoning are prevalent. CITES Appendix II. Red List: Least Concern. Population trend: Decreasing.