Leopard Cat

Prionailurus bengalensis (Kerr, 1792)

IUCN RED LIST (2008):

Least Concern (Global)

Least Concern (Global)

Vulnerable (Philippines)

Vulnerable (Philippines)

Critically Endangered (Iriomotejima)

Critically Endangered (Iriomotejima)

Head-body length ♀ 38.8−65.5cm, ♂ 43.0−75.0cm

Tail 17.2−31.5cm

Weight ♀ 0.55−4.5kg, ♂ 0.74−7.1kg

Taxonomy and phylogeny

The Leopard Cat is classified in the Prionailurus lineage where its closest relatives are the Fishing Cat and, more distantly, the Flat-headed Cat. Up to 12 subspecies are described including as many as seven island subspecies, but the taxonomy is in need of review. Limited genetic data suggest two highly variable subspecies on mainland Asia, divided into a northern subspecies, the Amur Leopard Cat P. b. euptilurus of the Russian Far East, north-eastern China, Korean Peninsula, Taiwan, and Japan’s Tsushima and Iriomote Islands; and a southern subspecies, P. b. bengalensis, occurring everywhere else on the mainland (excluding possibly the Malay Peninsula; see below). Some populations were formerly classified as separate species, now considered invalid, notably the Iriomote Cat on Japan’s Iriomote Island and the Amur Leopard Cat, both of which are now classified as P. b. euptilurus. There is recent genetic evidence that Leopard Cat populations south of the Kra Isthmus – on the Malay Peninsula, Borneo, Sumatra, Java and Bali – actually represent a separate Leopard Cat species (as for the now accepted separation of mainland and Sunda Clouded Leopards as two species, here). Further analysis of a wider sample will help to resolve this issue, including the classification of the Leopard Cat in the Philippines, which is usually considered the subspecies Visayan Leopard Cat P. b. rabori. Leopard Cats readily hybridise with domestic cats which is apparently reported from the wild in rural areas, though there is no physical evidence of wild hybrids.

Description

The Leopard Cat varies considerably in size and appearance, depending on the region and on the season in northern populations. The smallest adults are from tropical islands and can weigh less than 1kg compared to northern individuals that may exceed 7kg; there are exceptional records from Russia of 8.2–9.9kg during late summer to autumn when Leopard Cats are hyperphagic before the severe winter. Colouration is extremely variable. Individuals in mainland tropical Asia tend to be richly coloured with yellow to tawny-brown or ginger-brown fur, and bold markings varying from large solid dabs to rosettes and blotches with dark tawny edges or centres. Island forms, including those on Borneo and Sumatra, tend to be less strongly marked with small, discrete spots and dabs on a background colour that varies widely from drab ginger-brown to very dark brown. Iriomote Cats are very dark; some individuals are blackish-grey with indistinct markings except on the face and underparts. At the other extreme, Amur Leopard Cats in temperate Russia, Korea and China are very pale ginger-grey to silver-grey in winter with long, dense fur that moults to a darker, summer coat of russet-brown to grey-brown. Complete melanism does not occur although there are occasional records of pseudomelanistic individuals with extensive enlarging and coalescing of the dark markings.

Similar species Dark forms of the Leopard Cat are similar to the closely related Fishing Cat, which is considerably larger and more heavily built; very young kittens of both species can be indistinguishable. Leopard Cats might also be confused with the spotted form of the Asiatic Golden Cat, which is much larger with a long, more tapering tail.

An Amur Leopard Cat hunts birds in reeds at the edge of a frozen lake, Taean region, South Korea.

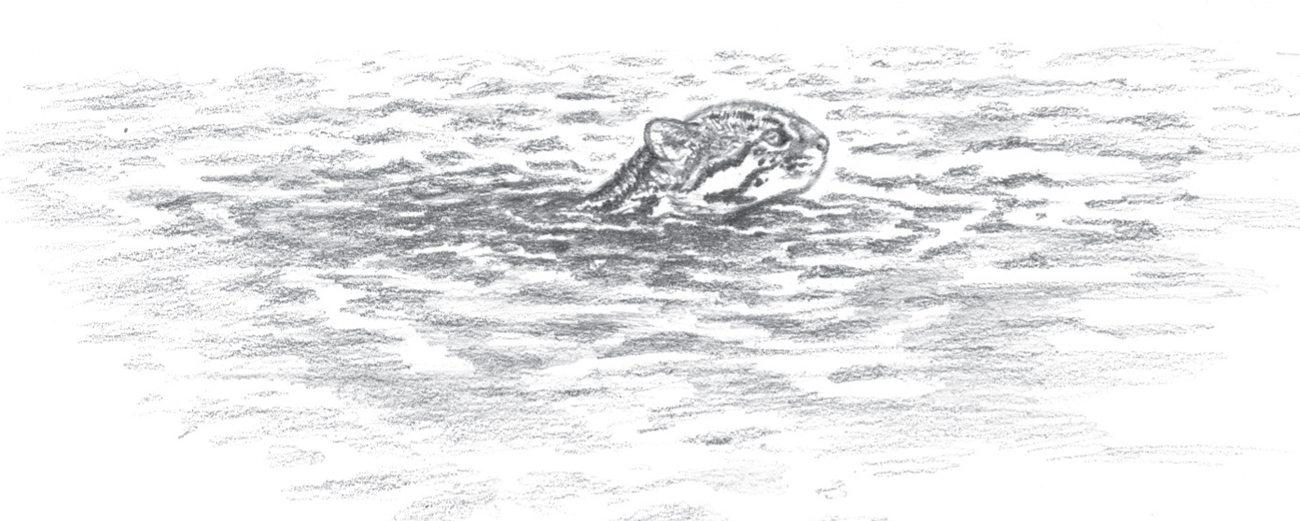

Like all members of the Prionailurus lineage, the Leopard Cat is often associated with water. Leopards Cats are strong swimmers that readily cross rivers or small lakes, and they frequently forage in shallows.

Island populations of Leopard Cats tend to have less richly marked coats than their mainland counterparts, as this individual in riverine forest on the banks of the Kinabatangan River, Sabah, Borneo.

Distribution and habitat

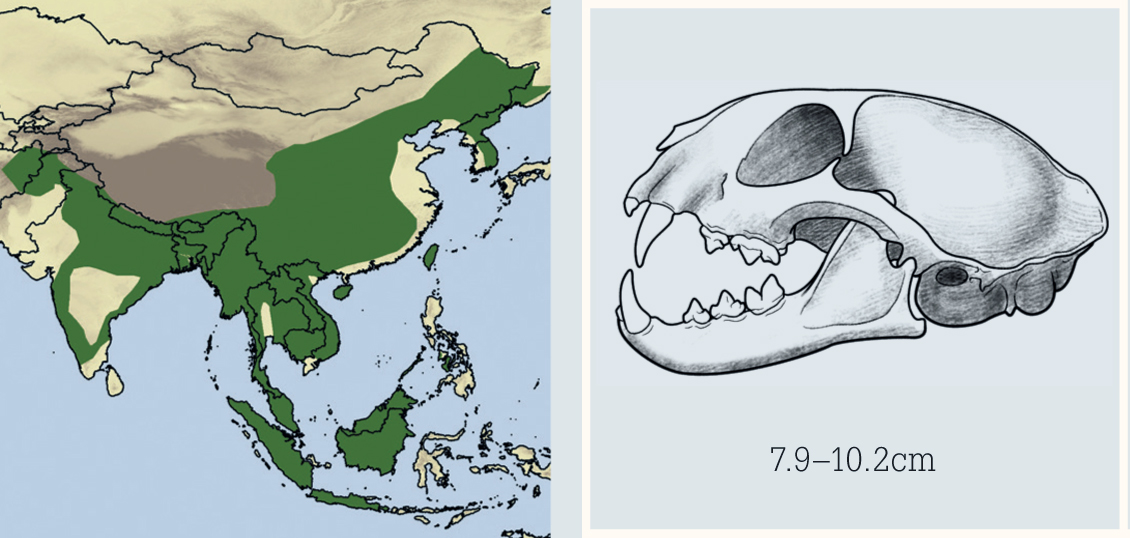

The Leopard Cat is the most widespread of all small Asian felids. It is found in tropical, subtropical and temperate Asia from the Russian Far East, north-eastern China and the Korean Peninsula, through eastern China to the Tibetan Plateau and in the Himalayan foothills as far west as central Afghanistan; from northern Pakistan, Nepal and Bhutan to southern India; and throughout South-east Asia, including on Borneo, Java and Sumatra. The Leopard Cat occupies more islands than any other felid including Hainan, Taiwan, the Philippine islands of Palawan, Panay, Negros and Cebu, and the Japanese islands of Iriomote and Tsushima; it is the only felid native to Japan. It is absent naturally from Sri Lanka.

The Leopard Cat occurs in a very wide variety of habitats with cover including all forest types ranging from lowland tropical rainforest to dry broadleaf and coniferous forest in the Himalayan foothills as high as 3,254m (eastern Nepal). They inhabit vegetated valleys in cold, temperate forest with winter snowfall in the northern range but they are limited to areas with shallow snow. They inhabit all kinds of woodland, scrub habitat, shrublands, marshes, wetlands and mangroves. They occur in wooded grasslands and shrub-grassland mosaics but they largely avoid open grasslands, steppes and rocky areas lacking vegetation. Leopard Cats are tolerant of human-modified habitats with cover including logged forest, farmlands such as sugar cane fields, and plantations of oil palm, coffee, rubber trees and tea. Leopard Cats may reach high densities in some open modified habitats that sustain high rodent numbers. They occur very close to human habitation, including in patches of suitable habitat in major metropolises, for example Miyun Reservoir and Yeyahu Nature Reserve in Beijing.

Feeding ecology

The Leopard Cat’s diet is made up primarily of very small prey, chiefly small vertebrates. In most well-studied Leopard Cat populations, the most important prey category is made up of various mice and rats supplemented with other small mammals including squirrels, chipmunks, tree shrews, shrews and moles. Larger mammals recorded in the diet include hares, langurs, Lesser Mouse Deer and Wild Boar, most of which were probably scavenged. In Russia, it is reported to attack neonate ungulates including Roe Deer, Sika and Long-tailed Goral provided they are under a week old and when unguarded by the mother. Leopard Cats also eat birds up to the size of pheasants, as well as herptiles and invertebrates. Three species of skinks, four snake species, a frog and a large cricket species are important prey to Iriomote Cats where rodents probably did not occur until humans introduced the Black Rat (which is now the most important prey by biomass). Leopard Cats are harmless to hoofstock but they prey on domestic poultry and are apparently easily captured with chickens as bait.

The Leopard Cat is a very active and versatile hunter that forages mainly on the ground and in low vegetation. However, it is an excellent, lightweight climber that is very much at home among slender branches and palm fronds where, although direct observations are few, hunting is bound to also occur. Similar to other Prionailurus felids, they have a strong affinity for water and are strong swimmers; they readily forage in the shallows for amphibians, freshwater crabs and other invertebrates. Hunting activity is variable, ranging from being strictly nocturnal at some sites to cathemeral, probably depending on prey availability and the presence of larger carnivores or humans. They readily scavenge, including reportedly inside caves where they eat dead or fallen bats and Cave Swiftlets. The cat also caches large kills; for example, a Ring-necked Pheasant was hidden in scrub and eaten by an Amur Leopard Cat over a number of sittings.

The Leopard is a known predator of Leopard Cats. The effects of predation on Leopard Cat populations are poorly known except where heavy human predation, in the form of fur harvest and persecution, almost certainly produces declines.

Social and spatial behaviour

The Leopard Cat follows the basic felid socio-spatial pattern. They are largely solitary with enduring ranges in which male ranges generally overlap one or more, smaller female ranges. Range size differs little between sexes in some populations, for example in Phu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary, Thailand. Overlap between same-sex adults is considerable at the range edges and is usually minimal in exclusive, core areas, yet core areas overlap significantly in Phu Khieo. Range size is 1.4−37.1km2 (females) and 2.8−28.9km2 (males). Leopard Cats urine-mark and scrape in typical felid fashion but the degree of territorial defence is unclear. Iriomote Cat adults were aggressive to each other at experimental feeding stations but this may have been heightened by the situation’s artificiality. Density estimates include 17−22 Leopard Cats per 100km2 (subtropical and temperate Himalayan forest, Khangchendzonga Biosphere Reserve, India), 34 Leopard Cats per 100km2 (Iriomotejima) and 37.5 Leopard Cats per 100km2 (lowland rainforest and adjacent oil-palm plantations, Tabin Wildlife Reserve, Sabah).

The Leopard Cat is often the most abundant felid where it occurs and the species most likely to be encountered by people (C).

Leopard Cats are very agile climbers that seek refuge in trees when threatened or pursued by predators (C).

Reproduction and demography

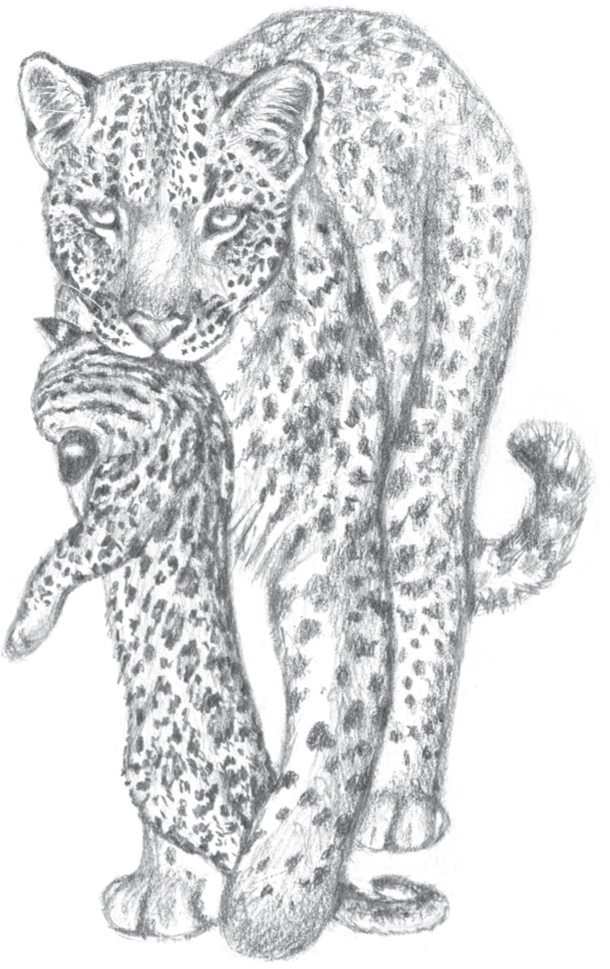

This is relatively poorly known from the wild but available information indicates that the species breeds aseasonally in most of its range, becoming more seasonal in temperate areas. The Amur Leopard Cat is apparently highly seasonal with births restricted to late February–May. Captive Leopard Cats are able to have two litters a year, though a single litter is probably typical in the wild. Gestation lasts 60−70 days. Litter size is one to four kittens, typically two to three. Sexual maturity occurs at 8−12 months (captivity); the earliest breeding in a captive female was at 13 months.

Mortality Estimated annual adult mortality varies from 8 per cent in a remote sanctuary with low human pressure (Phu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary, Thailand) to 47 per cent in an accessible protected area (Khao Yai National Park, Thailand). Mortality is likely even higher outside protected areas close to people. Leopard Cats are probably killed occasionally by a wide variety of natural predators given their small size but there are few records; Leopards and domestic dogs are confirmed predators and Wild Boar are suspected predators of kittens on Tsushima. Humans are the main source of mortality for many populations, for example in much of South-east Asia and China. Roadkills are the major factor on Iriomotejima (at least 40 deaths from 1982 to 2006) and Tsushima (at least 43 deaths from 1992 to 2006).

Lifespan Unknown in the wild, up to 15 years in captivity.

STATUS AND THREATS

The Leopard Cat is widespread, adaptable and is able to live near people where tolerated. It reaches high densities in suitable habitat (including some anthropogenic landscapes) and is the most abundant felid in most of its range. However, it is the only Asian cat legally harvested for fur, for which it is heavily hunted in its temperate range where densities are naturally lower than elsewhere in the range. In 1985–1988, as many as 400,000 Leopard Cats were killed annually in China for the fur trade. China suspended its international trade in 1993, when a stockpile of a staggering 800,000 skins was estimated. The cessation of international trade has apparently reduced hunting pressure, though Leopard Cats are still legally hunted in China outside protected areas and skins are very common in Chinese fur warehouses. The impacts of such high harvests are unknown. Although hunting is illegal in subtropical and tropical Asia, the species is nevertheless widely killed for fur and meat, and in retaliation for poultry predation. The species is also targeted for the pet trade and is frequently sold in wildlife markets, for example in Jakarta, Java and in Vietnam. Many island populations are small and threatened by rapid development. Populations on Tsushima and the Philippine islands of Panay, Negros and Cebu are declining. The Iriomotejima population numbers around 100 and is well protected in central montane habitats, but is declining in coastal lowlands. CITES Appendix I (Bangladesh, India and Thailand), Appendix II elsewhere. Red List: Least Concern (global), Critically Endangered (Iriomotejima), Vulnerable (Philippines). Population trend: Stable (global), decreasing on some islands.