Geoffroy’s Cat

Leopardus geoffroyi (d’Orbigny & Gervais, 1844)

IUCN RED LIST (2015): Least Concern

IUCN RED LIST (2015): Least Concern

Head-body length ♀ 43−74cm, ♂ 44−88cm

Tail 23−40cm

Weight ♀ 2.6−4.9kg, ♂ 3.2−7.8kg

Taxonomy and phylogeny

Geoffroy’s Cat is classified in the Leopardus genus and is most closely related to the Guiña with a shared ancestor estimated under a million years ago. Both species were formerly classified in the genus Oncifelis with the Colocolo but they are now firmly considered to represent a closely related sub-branch of the Leopardus genus together with the oncillas. Geoffroy’s Cats hybridise with the recently described Southern Oncilla (L. guttulus) in southern Brazil where the two species’ ranges overlap; this is an active hybridisation zone meaning that hybrids are fertile and interbreeding is ongoing, reflecting a very close evolutionary relationship between the two species. There are up to four subspecies described for Geoffroy’s Cats, but preliminary genetic analysis suggests few molecular differences across the range.

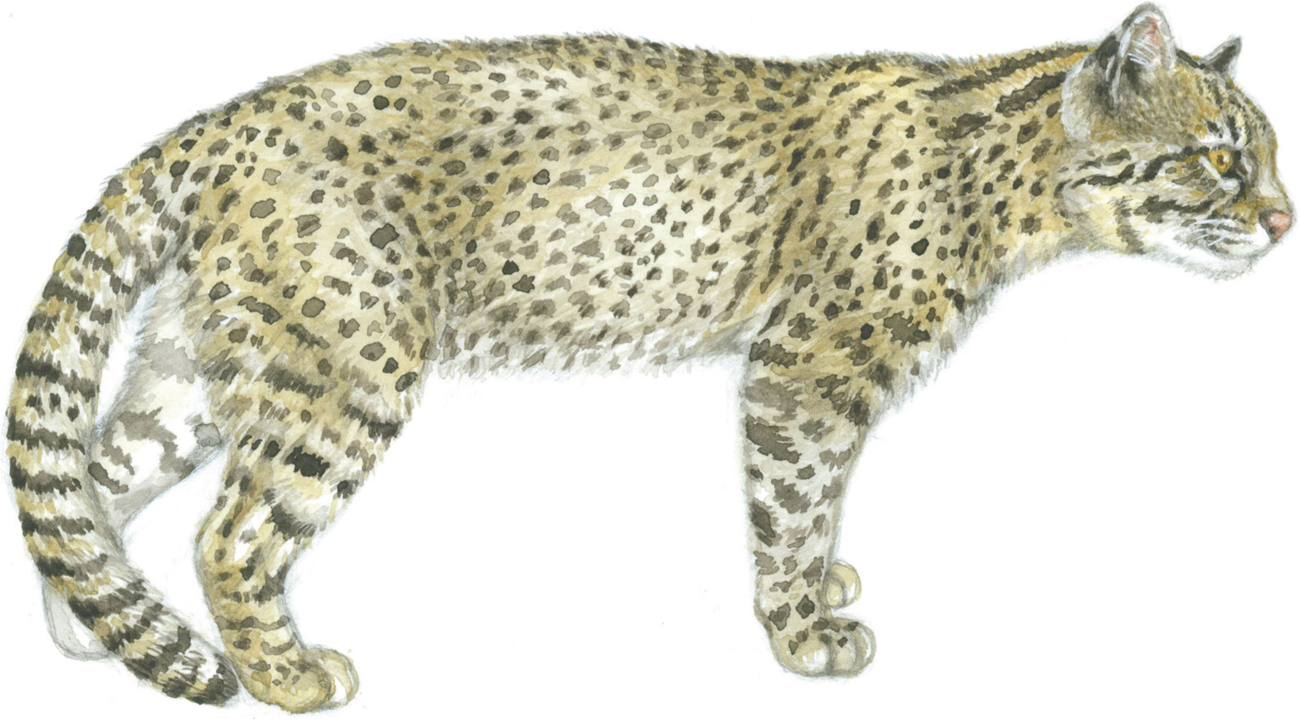

Description

Geoffroy’s Cat is the largest of the South American temperate zone small felids, reaching the size of a large domestic cat (Andean Cats may be comparable based on very few weighed individuals). Males are 1.2−1.8 times the weight of females. Body size varies considerably across the range (but not in a strong cline increasing from north to south, as often reported) possibly related to prey availability. Based on relatively few captured animals, average weight varies from 3.1kg (females)–3.7kg (males; Uruguay), 4.1kg (females)–5kg (males; Parque Nacional Torres del Paine, Chile), to 4.2kg (females)−7.4kg (males; Campos del Tuyú Wildlife Reserve, Argentina). The fur colour is variable, ranging from rich yellow-brown to pale buff and silver-grey; southern animals are typically pale coloured while richer tawny or reddish tones are more common in the north of the range. The body is covered with small, solid dab-like dark brown or black spots coalescing to blotches on the nape, chest and lower limbs. The tail has 8−12 narrow bands interspersed with small spots; the bands become wider towards the tail tip, which is dark. Melanism is common, particularly in Uruguay, south-eastern Brazil and eastern Argentina, but is generally rare elsewhere in the range.

Similar species Geoffroy’s Cat is very similar in appearance to the closely related Guiña, which is considerably smaller, generally has richer colouration and a distinctive bushy tail. The two species are known to overlap only at the extreme eastern edge of the Guiña’s range, for example Parque Nacional Los Alerces, southern Argentina, and Parque Nacional Puyehue, Chile.

A curious Geoffroy’s Cat in the Andes, central Bolivia. This cat was attracted to the photographer who imitated the squeaking sound of a small animal in distress.

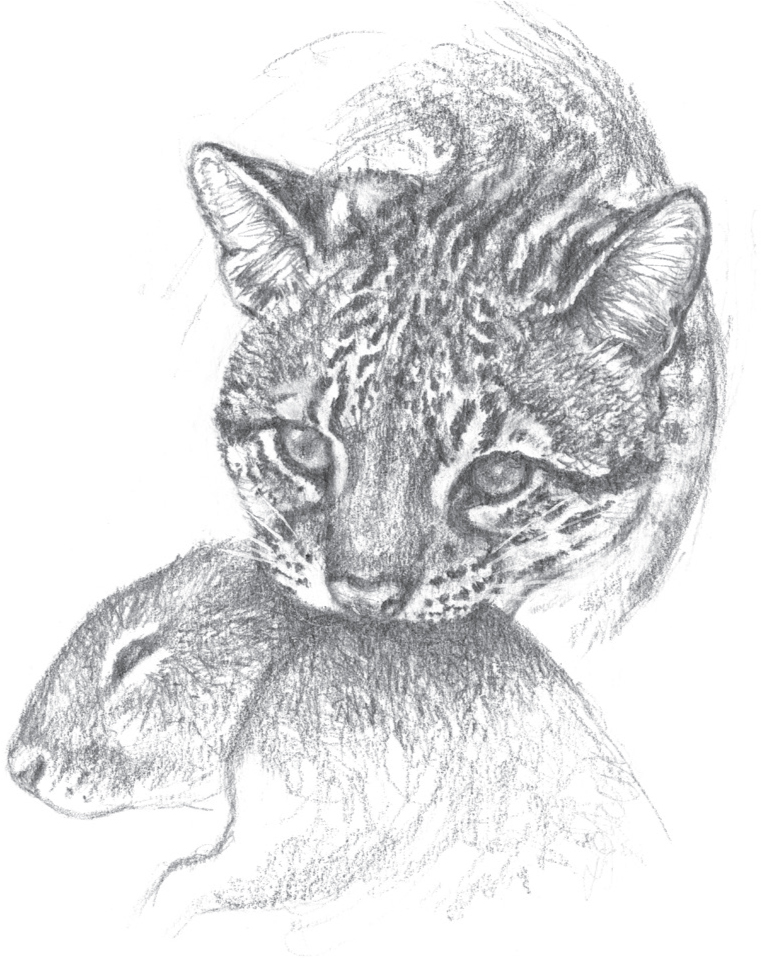

The scars on this male Geoffroy’s Cat’s face are probably from territorial clashes with other males. Although fights are rarely fatal, territorial adults of most cat species accumulate such facial scars over their lifetime. Older males in particular are often heavily scarred.

Distribution and habitat

Geoffroy’s Cats occur from central Bolivia through western Paraguay, extreme south-eastern Brazil and Uruguay and in most of Argentina to the Strait of Magellan in Chile; their distribution stops at the eastern Andes and extends marginally into southern Chile along the border with Argentina. Geoffroy’s Cats inhabit a wide variety of habitats including all kinds of subtropical and temperate brushland, woodlands, dry forest, semi-arid scrub, pampas grasslands, marshlands and alpine saline deserts, from sea level to 3,300m in the Andes. They occur in open grassland but typically in areas with wooded and brushy patches or well-vegetated marshland. They are not found in tropical or temperate rainforest. They occur in modified landscapes with cover such as ranchlands with scrub-grassland mosaics. They also occur in conifer plantations especially those with remnants of native vegetation – Geoffroy’s Cats collared in Ernesto Tornquist Provincial Park, central Argentina, avoided natural grasslands which were degraded by the presence of feral horses, and mainly used overgrown exotic woodlands outside the park. They are recorded using abandoned houses as shelters in pampas croplands.

Feeding ecology

Geoffroy’s Cat is a versatile generalist in which small vertebrates make up 78−99 per cent of the diet, the species composition of which varies according to the region and prey availability. In most populations, the diet is dominated by small rodents weighing up to 200–250g, including grass mice, rice rats, marsh rats and cavies, and small passerine birds; consumption of the latter typically increases during spring-summer migrations. Larger prey dominates according to the season and the site. Introduced European Hares (~2.5–3.2kg) have become important prey in many areas. Hares comprise more than half of the diet in southern Chile where Geoffroy’s Cats are large, but less so where cats are smaller; for example, only 2 per cent of the diet in Parque Nacional Lihue Calel, Argentina. Large waterbirds with an average weight of 1.3kg are most important for cats in coastal lagoon habitat (Mar Chiquita, Argentina) where 12 species are eaten, including Neotropic Cormorants, White-faced Ibises, coots, ducks, as well as occasional kills of larger species including Chilean Flamingos and Coscoroba Swans. Waterbirds are most important during spring when their abundance peaks; the diet shifts more to small rodents and hares in summer and autumn when birds migrate and their abundance declines. Incidental prey across the range includes Coypus (introduced), Six-banded Armadillos, hairy armadillos, tree porcupines, small opossums, small reptiles, amphibians, crabs, fish and invertebrates (mainly beetles, which contribute little to energetic requirements). They readily raid domestic poultry; sheep recorded in the diet (for example, in southern Brazil) is probably scavenged.

Geoffroy’s Cats are primarily nocturno-crepuscular throughout their range, with activity increasing as dusk approaches and peaking between 21:00 and 04:00. During a severe drought and collapse of prey populations in and around Lihue Calel in 2003, radio-collared Geoffroy’s Cats were primarily diurnal, presumably in search of food. They returned to nocturno-crepuscular foraging patterns when the drought had passed, with 93 per cent of activity records occurring from 20:00 to 06:00. Geoffroy’s Cats mostly forage on the ground in search of small rodents and birds in ground vegetation; although they climb very well, there are no observations of arboreal hunting. They readily swim and hunt in marshy habitat; Coypus, marsh rats, birds, frogs and fish are taken at the water’s edge. Geoffroy’s Cats in coastal lagoon habitat launch attacks on waterbird roosting areas from dense grassy vegetation in the shallows at the edges of colonies. Geoffroy’s Cats cache large kills. They were observed twice hauling European Hare carcasses into Nothofagus trees in Chile, and a female Geoffroy’s Cat in Argentina failed in an attempt to haul a Red-legged Seriema 4m into a tree; she later stored the carcass in a burrow which she also occupied.

A Geoffroy’s Cat killing a wild cavy with a nape bite, an efficient technique used by all cats to rapidly dispatch small prey. Large prey, with proportionally broader, more muscular necks, are less vulnerable to a nape bite and are usually killed by a throttling bite to the throat.

Social and spatial behaviour

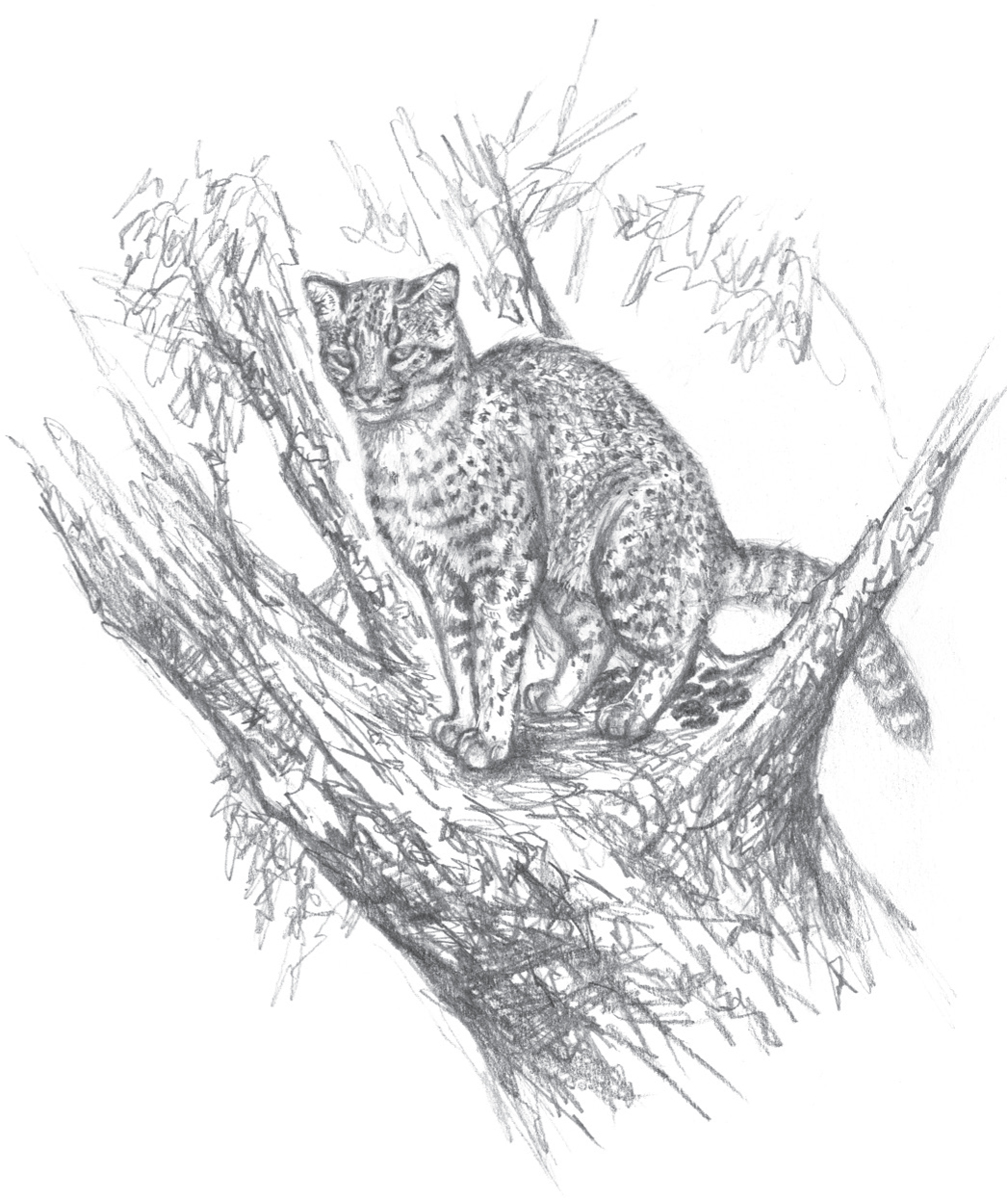

Geoffroy’s Cat is solitary; males occupy larger home ranges than females, and one male range typically overlaps multiple female ranges. Some radio-tracking data show that home ranges are not stable and that Geoffroy’s Cats readily abandon their ranges to become transient, but it is likely that those populations were monitored during periods of extreme ecological stress and high population turnover, for example, in Parque Nacional Lihue Calel where only 11 per cent of the cats identified during a protracted drought in 2006 were found two years later. In Torres del Paine National Park, Chile, an adult female maintained the same range for three years and a young female captured as a juvenile was still in the same area two years later. The degree of territorial defence is unknown but Geoffroy’s Cats mark their ranges assiduously; unusually for felids, they often deposit faeces in certain trees which they repeatedly mark over time, creating conspicuous, arboreal middens. For example, 93 per cent of 325 faeces collected in Torres del Paine were in arboreal middens 3–5m high, typically where the main trunk diverged into several branches creating a natural platform or bowl. Middens on the ground are also used. Across five protected areas in Argentina, 47.6 per cent of all defecation sites were in trees: 38.1 per cent were on the ground, mainly along trails, and the remainder were in burrows.

Range sizes average 1.5−5.1km2 (females) and 2.2−9.2km2 (males); the largest ranges are found in disturbed habitat (agricultural-woodland mosaic, east-central Argentina). Per day, radio-collared cats move on average 583m (females; up to 1,774m) to 798m (males; up to 1,942m) in well-protected Argentine pampas, compared to 680m (females; up to 2,859m) to 1,213m (males; up to 3,704m) in disturbed agricultural-woodland mosaic. Rivers do not restrict their movements; a radio-collared female in Chile regularly crossed a 30m wide fast-flowing river in her territory, and two young males swam the same river when dispersing. Density estimates range from four cats per 100km2 (Argentine pampas during an extreme drought and prey shortage) to 45–58 cats per 100km2 in ranchlands of the Argentine Espinal. A very high estimate of 139 cats per 100km2 from protected Argentine scrublands may be an overestimate.

Although not nearly as richly marked as other neotropical cats such as the Margay and Ocelot, Geoffroy’s Cat was formerly killed in huge numbers for its spotted fur. It is now fully protected across its range although some illegal local hunting for fur still takes place (C).

Geoffroy’s Cat is very unusual among felids in depositing faeces in latrines called middens; it is even rarer that most latrines are in trees such as the Nothofagus shown here. Latrine use is also known from the related Colocolo and Ocelot although it is less common and largely terrestrial.

Reproduction and demography

Poorly known from the wild, but Geoffroy’s Cats are considered to breed seasonally in the southern part of their range where winters are very cold; based on limited observations, births occur between December and May. In captivity, they breed year-round and there is no evidence for seasonality in the northern part of the range. In captivity, gestation lasts 62−78 days and litter size is one to three kittens. Wild females den in burrows (probably created usually by armadillos), in thick vegetation and possibly in tree cavities (which are definitely used as rest sites by adults). Kittens achieve adult size (but not weight) at around six months of age but sexual maturity is surprisingly late for a small cat, at 16−18 months (captivity).

Mortality Pumas are known predators and there is one case of probable predation by a Culpeo Fox. Severe droughts with collapses in prey numbers have been shown to elevate mortality considerably due to starvation combined with high parasite loads. Where studied, people and domestic dogs are usually the main source of mortality.

Lifespan Unknown in the wild, up to 14 years in captivity.

STATUS AND THREATS

Geoffroy’s Cats are widely distributed and are found in a broad range of habitats including some highly disturbed landscapes. They reach high densities in good habitat and are considered common in much of their range. However, threats are poorly understood. They were killed in huge numbers for their furs throughout the 1970s and 1980s, particularly in Argentina which exported at least 350,000 skins from 1976 to 1980. Their abundance was a factor in the massive trade, but there is no doubt the trade was unsustainable and led to reductions and extirpation in some areas. International trade in spotted cat furs ceased in the late 1980s and the fur trade is no longer a major threat, although domestic (and illegal) use of their skins continues in some places. The primary threat today is habitat conversion, for example to agricultural monocultures that even Geoffroy’s Cats cannot occupy. Additionally, they are often killed on roads, by domestic dogs, and by people for depredation on poultry, all of which probably exacerbates the threats to populations already under pressure in modified landscapes. Geoffroy’s Cats in two Argentinean protected areas (Parque Nacional Campos del Tuyú and Parque Nacional Lihue Calel) tested positive for exposure to a wide variety of domestic carnivore diseases and parasites, though no effects on individuals or populations were observed.

CITES Appendix I. Red List: Least Concern. Population trend: Decreasing.