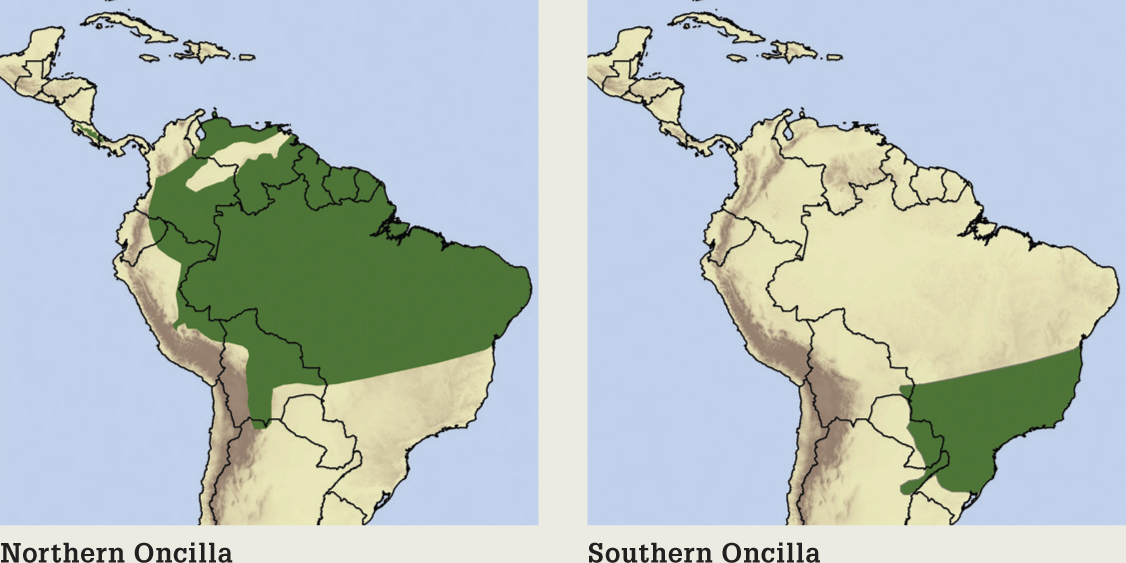

Northern Oncilla/Southern Oncilla

Leopardus tigrinus/Leopardus guttulus

(Trigo, Schneider, de Oliveira, Lehugeur, Silveira, Freitas & Eizirik, 2013)/(Schreber, 1775)

Little-spotted Cat, Tiger Cat

IUCN RED LIST (2008): Vulnerable

IUCN RED LIST (2008): Vulnerable

Head-body length ♀ 43−51.4cm, ♂ 38−59.1cm

Tail 20.4−42cm

Weight ♀ 1.5−3.2kg, ♂ 1.8−3.5kg

Taxonomy and phylogeny

Oncillas belong in the Leopardus genus, and they have intriguing evolutionary relationships with the other cats of this lineage. Until 2013, the Oncilla was considered a single species but recent genetic analysis has revealed two closely related ‘cryptic’ species that have been evolutionarily separate for at least 100,000 years. Oncillas in north-eastern Brazil (L. tigrinus) are distinct from those in southern Brazil (now considered L. guttulus), which presumably also applies to populations in the Amazon Basin and northern South America. Their respective ranges meet in central Brazil where the two species overlap but apparently do not interbreed. Southern Oncillas hybridise with Geoffroy’s Cats in the wild while Northern Oncillas do not, and yet they show evidence of historical hybridisation with the Colocolo. Oncillas elsewhere in Latin America were not included in the analyses, but earlier sampling showed that the Costa Rican population was distinct from southern Brazilian oncillas, and it is currently considered a discrete subspecies, the Central American Oncilla L. tigrinus oncilla. It is possible that further research will describe more cryptic species.

Description

The oncillas are the second smallest tropical Latin American cats, with a slender, lightly built body about the size and proportions of a young, lean domestic cat. The fur colour ranges through shades of pale to dark buff or ochre marked with orderly rows of black or dark brown blotches or small rosettes with a coffee-brown or reddish centre. The two recently described species are extremely similar in appearance. There is apparently a slight trend for L. tigrinus to be more lightly coloured with smaller rosettes than L. guttulus. Melanistic individuals are recorded.

Similar species Oncillas are very easily confused with the Margay, which is larger, more richly marked and has a distinctively longer tail.

Outwardly, the two oncilla species are extremely difficult to distinguish, especially above the neck. Both have a small, very lightly built head suited for very small prey that rarely weighs more than 500 grams (C).

Distribution and habitat

Oncillas occur from northern Venezuela to southern Bolivia, eastern Paraguay, far southern Brazil and extreme northern Argentina; the boundary between the two newly described species appears to be central Brazil (and possibly across the Bolivian range, which is likely to be L. guttulus). There is a disjunct population in the central cordillera of Costa Rica and north-west Panama (the Central American Oncilla, which might comprise a third species). Both Oncilla species occur in a broad range of habitats including all types of forest, woodlands, wet and dry savannas, arid scrublands and coastal restinga (scrub on sandy beaches). They live from sea level to 3,200m, and exceptionally at 3,626m (Costa Rica) to 4,800m (Colombia). In Central America, they are restricted to oak-dominated cloud and elfin forests above 1,000m. In Brazil, there is speculation that Northern Oncillas L. tigrinus occur mainly in open, dry habitats while Southern Oncillas L. guttulus are mainly forest-living. They are strangely absent from or very rare in Amazon Basin lowland rainforest, though this might reflect poor sampling. Oncillas can occupy degraded habitats close to people including rangelands, plantations, agricultural mosaics and peri-urban areas even near large cities, provided there is dense cover.

Measured by how often they appear in scats, small birds such as this tinamou consistently rank as the second most important prey for oncillas; small mammals are usually the most important. This is a Southern Oncilla (C).

Feeding ecology

Oncilla prey is typically very small, averaging 100–400g and is not recorded exceeding 1kg. Typical prey includes small rodents, shrews, small opossums, small birds and reptiles. Invertebrates often appear in scats but contribute very little to energetic requirements. Mid-sized diurnal lizards (ameivas and small iguanas) dominate the diet in semi-arid caatinga, north-eastern Brazil, where rodent densities are low. There are few direct observations of hunting but the species’ prey profile indicates that they forage mainly terrestrially and nocturno-crepuscularly but with some flexibility depending on prey activity (and possibly the presence of Ocelots which they might avoid). Oncillas are more diurnal in the caatinga reflecting their reliance on diurnal reptiles. They rarely take poultry.

Social and spatial behaviour

Oncillas likely follow a typical felid solitary socio-spatial pattern but their ecology is poorly known. Range size has been calculated for eight individuals only from Brazilian savannas and agricultural-forest mosaics where estimates are 0.9−25km2 (females) and 4.8−17.1km2 (males). Density estimates from camera-trapping suggest they are naturally rare compared to other small felids in Latin America: 0.01 per 100km2(lowland Amazon forest) to 1−5 per 100km2in other areas of the range. They apparently reach 15−25 per 100km2in areas where Ocelots are absent, presumably due to release from competition and predation.

A pair of Northern Oncillas during courtship, the female signalling her receptivity by lordosis in which she lowers her forequarters and raises the hips. There is no recorded observation of wild oncillas mating but the behaviour is assumed to follow a typical felid pattern.

Reproduction and demography

Unknown from the wild. Limited information from captive individuals indicates gestation is 62−76 days and litter size is one and rarely two kittens.

Mortality Poorly known – there is a single record of an Ocelot killing an adult, and a Brazilian female died of heartworm disease. Domestic dogs are likely to be a significant predator in anthropogenic landscapes.

Lifespan A female lived to 17 years in captivity, but longevity is certain to be much less in the wild.

STATUS AND THREATS

Oncillas are camera-trapped at very low rates in most areas and are regarded as naturally rare. Habitat loss is the main threat. Although some populations occupy modified habitats, they are closely associated with dense cover especially in Central America and the Andean forests of Colombia and Venezuela where oncillas have become locally extinct as a result of forest conversion to agriculture. They were very heavily hunted for the fur trade until exports were banned in 1973–1981; some domestic trade in furs still occurs. Localised killing for furs, by dogs, in retaliation for killing poultry and as roadkill probably impacts populations close to people.

CITES Appendix I. Red List: Vulnerable. Population trend: Decreasing.