Ocelot

Leopardus pardalis (Linnaeus, 1758)

IUCN RED LIST (2008): Least Concern

IUCN RED LIST (2008): Least Concern

Head-body length ♀ 69−90.9cm, ♂ 67.5−101.5cm

Tail 25.5−44.5cm

Weight ♀ 6.6−11.3kg, ♂ 7.0−18.6kg

Taxonomy and phylogeny

The Ocelot is classified in the Leopardus genus (and lineage of the same name), and is most closely related to the Margay. The species shows high genetic heterogeneity across its range, with four distinct population clusters: southern South America separated from all populations to the north by the Amazon River; northern South America which comprises two clusters – eastern Panama, north-west Brazil, Venezuela and Trinidad (and presumably Colombia which was not sampled), and northern Brazil and French Guyana (Suriname and Guyana were not sampled); and Central America and Mexico. This would suggest four subspecies, although up to 10 are currently described; most are probably invalid.

Description

The Ocelot is the third largest cat in Latin America. The smallest adult females are about the weight of a large domestic cat. The Ocelot is robustly built with thickset limbs and a relatively short, tubular tail typically too short to reach the ground (but exceptions exist). The head is powerfully built with a blocky muzzle, especially in adult males, and rounded ears that are black with a white central spot on the back. The paws are heavily built, especially the forepaws that are much larger than the hindpaws (giving rise to various local names such as manigordo or ‘fat hand’). The body fur is dense and soft, and very variable in background colour within and between populations, including shades of creamy-buff, tawny, cinnamon, red-brown and grey, with white underparts. Ocelots are very richly marked with highly variable combinations of black open and solid blotches, streaks and rosettes with russet-brown centres. Simple solid spots or blotches usually cover the lower legs, and the tail has black partial or complete rings with a black tip.

Similar species The Ocelot is very similar to the Margay but usually considerably larger, more heavily built and with a distinctively shorter tail. Young kittens of Ocelot, Margay and oncillas can be very difficult to tell apart.

All cats have highly sensitive whiskers or vibrissae that assist with moving in near or total darkness and also help them react instantly to the movements of prey at the moment of the killing bite. Cats also possess a second type of long tactile hair called a tylotrich scattered thinly over the body in among the less sensitive guard hairs.

Distribution and habitat

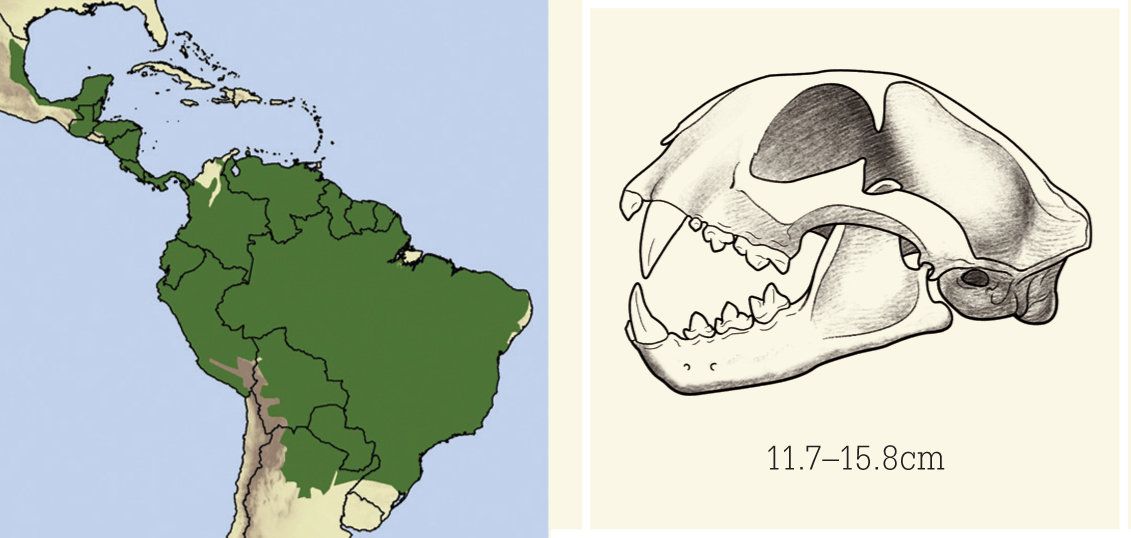

The Ocelot occurs from northern Mexico throughout Central and South America to south-eastern Brazil and northern Argentina including on Trinidad (with recent camera-trap confirmation from 2014) and Isla de Margarita, Venezuela. It does not occur in Chile and its presence in Uruguay is now uncertain although it occurs in Brazil very close to the border. The Ocelot formerly occurred in the southern US from Arizona to Arkansas and Louisiana but the only remaining breeding populations occur in two isolated fragments (Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge and Willacy County) in extreme southern Texas, numbering a total of 60−100 animals. Between 2009 and 2013, at least four male Ocelots were photographed in the Huachuca Mountains, Santa Rita Mountains and Cochise County of southern Arizona. Ocelots occur in a wide range of habitats including dense thorn-scrub, shrub woodlands, wooded savanna grasslands, mangroves, swamp-woodland mosaics and all kinds of dry and moist forest, but they strongly prefer dense cover within all habitat types and are not nearly as generalist as comparable species, for example the Bobcat. They are tolerant of modified habitat provided there is dense vegetation and prey; they occur in secondary forest and agricultural landscapes with extensive brush such as fallow cultivation. They mostly avoid very open areas but readily hunt in pasture and grasslands close to cover, especially at night. Ocelots are usually found between sea level and 1,200m, rarely up to 3,000m.

The size of Ocelots differs across the range although not along a north–south cline as often reported. Habitat type is the main determinant of differences, with rainforest cats being the largest and those from dry habitats such as scrub, chaparral and dry forest being the smallest.

Feeding ecology

The Ocelot is muscularly built with large, very powerful forepaws and a robust skull with large canines, a prominent sagittal crest and strong zygomatic arches conferring great biting power. These adaptations enable the Ocelot to overpower large prey including sloths, tamanduas, howler monkeys, juvenile Collared Peccaries and juvenile White-tailed Deer; there are also records of Ocelots feeding on adult Red Brocket Deer, though it is unclear if they were scavenged. Despite this, and based on early studies, the Ocelot has long been regarded as subsisting principally on very small mammals weighing less than 600g. A more accurate picture of the Ocelot’s diet lies somewhere between these extremes. For many populations, the most important prey category comprises medium-sized vertebrates, mainly large rodents such as acouchis, agoutis and pacas, opossums, armadillos and, in some cases, large reptiles particularly Green Iguanas (~3kg). This is supplemented by frequent kills of very small rodents which, although eaten often, may contribute less to intake. Ocelot diet is flexible and the relative importance of these prey categories varies depending on the region and availability of species. The largest prey (on average) killed is by Ocelots on Barro Colorado Island, Panama, where they eat mainly Hoffmann’s Two-toed Sloth, Brown-throated Sloth, and agoutis (33 per cent of their diet compared to a range of 0 per cent in Brazilian Atlantic Forests to 10.7 per cent in Iguaçu National Park, Brazil) as well as pacas, Green Iguanas and White-nosed Coatis.

Other relatively common prey includes squirrels, rabbits, cavies, tree porcupines and small primates, such as tamarins and squirrel monkeys, as well as birds including tinamous, guans, woodpeckers and doves. Ocelots readily consume aquatic and semi-aquatic prey including fish, amphibians and crustaceans, indicative of their ability to live in inundated habitats. Ocelots are highly opportunistic and shift prey preferences depending on availability; for example, large land crabs are heavily consumed when they become abundant during the wet season in Venezuelan llanos (flooded savanna). Incidental prey includes virtually any small species encountered, with records of bats, lizards, snakes, small turtles, caimans (presumably hatchlings) and arthropods. Relatively few carnivores are recorded in the diet – coatis and Crab-eating Raccoons are the most common carnivores killed, otherwise there are single records of olingo, Kinkajou, Crab-eating Fox, Tayra, Lesser Grison, Margay and oncilla as prey. Reptile and bird eggs are opportunistically eaten. There are no records of cannibalism except very rarely in captivity. Ocelots sometimes kill poultry but otherwise are not recorded preying on domestic animals.

Ocelots have been observed moving at all times of day but camera-trapping clearly shows they are primarily nocturno-crepuscular, with most activity taking place between 20:00 and 06:00. Diurnal activity increases on overcast, cool days and during the wet season (e.g. in Venezuelan llanos, which has more cloudy days). A Peruvian radio-collared mother with a kitten increased her diurnal foraging so that she was active for 17 hours a day, presumably to feed them both. Direct observations of hunting are surprisingly rare given Ocelots are widespread and often the most abundant felid present. Hunting is chiefly terrestrial, though they are adept climbers and the relatively high frequency of arboreal species in the diet suggests some prey is taken in trees – there is one record of an Ocelot attacking a young Mantled Howler Monkey in a tree (Barro Colorado Island). The Ocelot appears to adopt two main hunting techniques: scanning and listening for prey while quietly walking, interspersed with periods of sit-and-wait ambush hunting. In the latter technique, they may sit for up to an hour, often on an elevated point such as a fallen tree, to wait for prey to give away its location. Although Ocelots hunt mostly in or near dense cover, they frequently search for prey along trails, on river or coastal beaches and at the edge of open areas where prey is abundant and easily detected. The Ocelot is an excellent swimmer and frequently traverses large rivers; while there is no evidence for hunting in deep water, Ocelots forage in shallow water at the edges of water bodies and in sodden habitats such as seasonally flooded savannas (e.g. llanos and Pantanal). Ocelots kill most small to medium-sized prey by biting the nape or skull; for example, six Central American Agoutis weighing 2–3kg were killed by a skull bite (Barro Colorado Island).

Ocelots readily scavenge, for example from refuse piles left by people fishing in the southern Pantanal, Brazil, where Ocelots visit known dumpsites nightly to eat fish offal. They frequently cache food by covering it entirely with leaf and soil debris, and may return to feed on kills covered in this way over a number of nights.

Cats are wonderfully attuned to hunting possibilities as they move through their environment. Uncertain of a possible target, this Ocelot raises itself on its back legs and silently scales a nearby tree to gather more information before deciding on the hunt.

On Barro Colorado Island in Panama, Ocelots have been observed killing sloths when they come to the ground to defecate and are at their most vulnerable. In the canopy, their camouflage and famously slow movements make them extremely difficult to spot but they are occasionally taken in trees by the Ocelot.

An Ocelot kills a Green Iguana, Barro Colorado Island, Panama. Among well-studied Ocelot populations, iguanas rank in the top three prey species in at least three forest sites in Costa Rica, Panama and Mexico.

Social and spatial behaviour

The Ocelot is solitary, with a typical felid socio-spatial pattern where studied. Adults maintain enduring home ranges, usually with exclusive core areas and considerable overlap at the edges. Male ranges are generally double to four times the size of female ranges, and are less exclusive with greater overlap at the edges. Adults patrol and scent-mark ranges that are defended against same-sex conspecifics in sometimes fatal fights. Resident adults of both sexes are tolerant of their offspring, which may linger in the natal range for more than a year after independence, with some evidence of regular interaction. Like most felids, familiar Ocelots are likely to interact with each other regularly even if most hunting and other daily activities are solitary. Unfamiliar immigrants risk aggression from residents, especially males, which are responsible for the deaths of some dispersers. For example, two transients seeking territory were killed by resident males in Texas (comprising 7 per cent of 29 deaths between 1983 and 2002).

Estimates of range size by radio-telemetry have been conducted in Argentina, Belize, Brazil, Mexico, Peru, Venezuela and the US. Territories are quite small compared to similar-sized felids; the smallest ranges are in seasonally flooded savannas (Brazilian Pantanal and Venezuelan llanos), and the largest in dry cerrado savannas (Emas National Park, Brazil). Male ranges (average 5.2−90.5km2) overlap multiple, smaller female ranges (average 1.3−75km2). Ocelots appear to reach higher densities than all smaller felids in virtually all cases in which they have been studied, and reach very high numbers in good habitat. Density estimates include 2.3−3.8 per 100km2 (tropical pine forest, Belize), 13–19 per 100km2 (Atlantic Forest, Brazil), 26 per 100km2 (tropical rainforest, Belize) and 52 per 100km2 (dry Chaco-Chiquitano forest, Bolivia).

An Ocelot with captured Cobalt-winged Parakeet it has batted from the air at a clay lick where the parrots congregate for minerals, Tambopata National Reserve, Peru.

Like all cats, Ocelots leave information for conspecifics through a variety of territorial markings from claw raking, urination and defecation. Ocelots are known to occasionally use communal latrines including, in one case, the concrete floor of a small observation shelter.

Reproduction and demography

The Ocelot has unexpectedly low reproductive rates, with fairly long gestation, very small litters and long inter-litter intervals such that the lifetime reproductive output per female is only about five young, similar to (and, in some cases, fewer than) the output of large felids. Breeding is aseasonal. Gestation is 79−82 days. Litter size is one to two, with a single kitten being most common in captivity – litters of three have been recorded exceptionally in captivity. Kittens are slow to mature and reach independence at 17−22 months, and they may stay in the natal range until two to three years old. Dispersal appears to follow a typical felid pattern with males dispersing farther than females, though data (especially for females) are limited, and most monitored dispersers died before settling. Dispersal distances range from 2.5 to 30km. Six surviving Texan dispersers (of nine monitored) settled 2.5−9km from their natal ranges.

Mortality Rates are unquantified for most populations. Average annual mortality in Texan Ocelots ranges from 8 per cent for resident adults to 47 per cent for dispersing subadults; 45 per cent of mortality in this population is anthropogenic, primarily from roadkills, compared to 35 per cent from natural causes (the balance due to unknown causes). Known predators include Jaguars, Pumas and domestic dogs. There is one record each of an adult killed by a Boa Constrictor and an American Alligator (Texas). Ocelots are presumably vulnerable to large anacondas, caimans and perhaps Harpy Eagles. One collared Ocelot in Texas died after a rattlesnake bite.

Lifespan Unknown in the wild, 20 years in captivity.

Despite the Ocelot being widespread and common in many areas, its reproductive ecology is poorly understood. The survival rate of kittens is essentially unknown from the wild.

STATUS AND THREATS

The Ocelot is widespread, occupies a wide range of habitats and is able to reach high densities. It is considered secure and common in much of its range. Range loss is prevalent at the extremes of its historical distribution where it is now extinct or relict, especially in the southern US, northern and western Mexico, much of eastern and south-eastern Brazil, Uruguay and northern Argentina. Through much of the remaining, current range, the species occupies extensive areas of continuous or near-continuous distribution.

Nevertheless, the Ocelot depends on dense habitat and has very low reproductive potential, making it vulnerable to human pressures, and it is poorly equipped to recover or recolonise after threats subside. Habitat destruction is the main driver of declines, together with illegal hunting. Ocelots were once intensively hunted to fill the demand for spotted fur, with 140,000–200,000 skins exported annually from Latin America during the 1960s and 1970s. International trade became illegal in 1989 and hunting is prohibited by all range states, but hunting is still fairly widespread, for recreation and to sell furs into illegal domestic trade and international smuggling. Ocelots are easily hunted by treeing with dogs, a common practice across much of the range especially in ranching landscapes. Ocelots are also often killed intentionally or as bycatch in retaliation for poultry depredation. Humans may compete for Ocelot prey as key prey species, such as pacas, agoutis and armadillos, are very widely hunted by people throughout the range, and the two most important prey species for Ocelots in Jalisco, Mexico – White-tailed Deer and Spiny-tailed Iguana – are hunted heavily for human consumption.

CITES Appendix I. Red List: Least Concern. Population trend: Decreasing.