Guiña

Leopardus guigna (Molina, 1782)

Guigna, Kodkod, Chilean Cat

IUCN RED LIST (2015): Vulnerable

IUCN RED LIST (2015): Vulnerable

Head-body length ♀ 37.4−51cm, ♂ 41.8−49cm

Tail 19.5−25cm

Weight ♀ 1.3−2.1kg, ♂ 1.7−3kg

Taxonomy and phylogeny

The Guiña is classified in the Leopardus genus and is most closely related to Geoffroy’s Cat with a shared ancestor estimated at less than a million years ago. Both species were formerly grouped in their own genus Oncifelis with the Colocolo. The most recent consensus is the two species clearly represent a sub-branch of the Leopardus genus together with the oncillas to which both are related. Two Guiña subspecies are described, with moderate morphological and genetic differences. L. g. guigna occurs in southern Chile and is apparently slightly smaller and more brightly coloured than the paler L. g. tigrillo of central Chile.

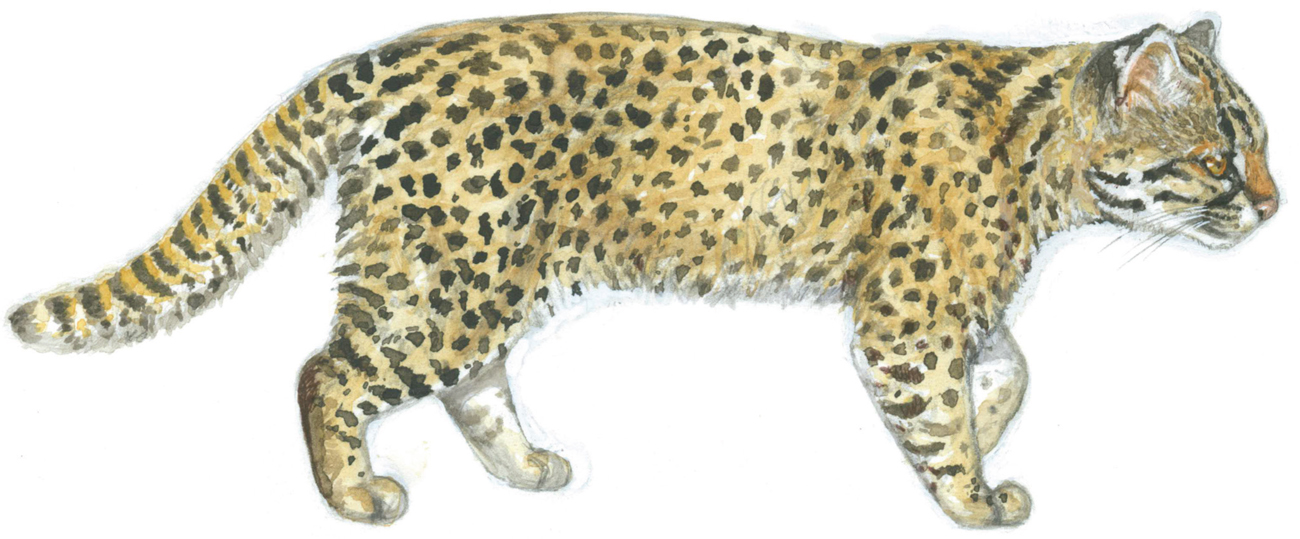

Description

The Guiña is the smallest cat in the Americas. It is a tiny, compactly built species with relatively short limbs and a thick, tubular bushy tail. The fur is greyish-brown to rich russet-brown marked with small, dark dab-like spots that coalesce into broken lines on the back and nape. The head is small and rounded, with a compact face that is distinctively marked with dark cheek stripes, eyebrow markings and prominent dark stripes under the eyes that border the muzzle; this gives the Guiña’s face a superficial resemblance to a Puma kitten. Melanism is common, sometimes with mahogany brown (rather than black) extremities on which the markings are obvious. At two sites in southern Chile 16 of 24 captured individuals were black.

Similar species The Guiña is very similar in appearance to the closely related Geoffroy’s Cat, which is larger with a relatively heavier head and less bushy tail. The two species are known to overlap only at the extreme eastern edge of the Guiña’s range, for example in Los Alerces National Park, southern Argentina and Puyehue National Park, Chile.

A melanistic Guiña kitten in the Parque Nacional Laguna San Rafael in Chile. The Laguna San Rafael population occurs on the Taitao Peninsula at the southernmost limit of the species’ range, isolated from other populations by extensive ice fields to the east.

This captive adult female Guiña is the larger, more lightly coloured northern subspecies L. g. tigrillo that occurs in Central Chile (C).

Distribution and habitat

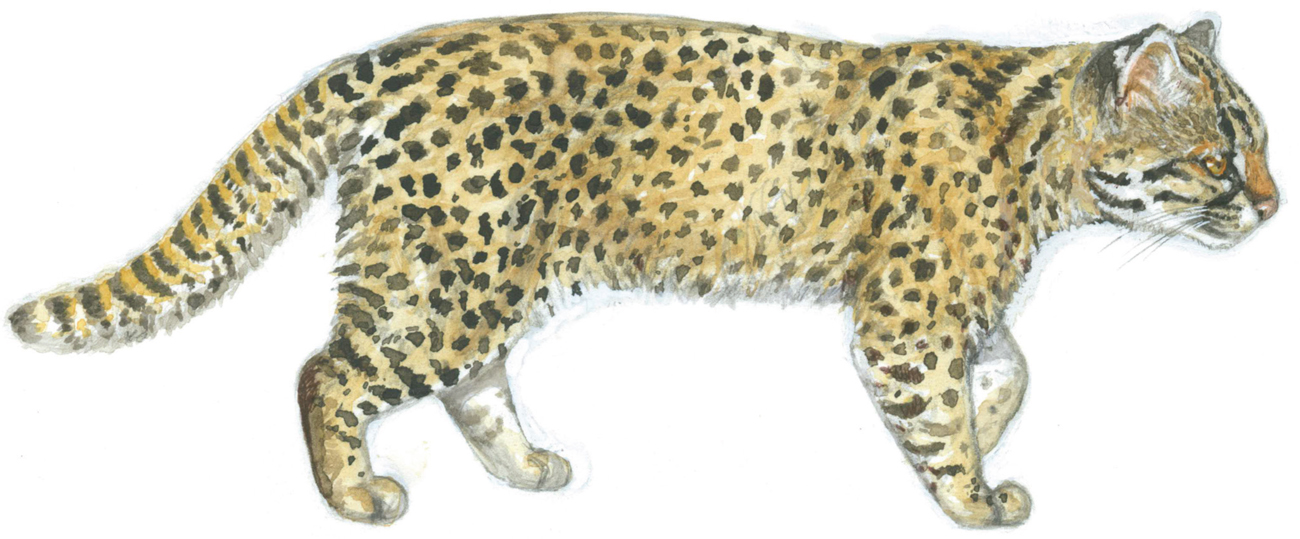

The Guiña has the smallest distribution of any Latin American cat, restricted to central and southern Chile including Isla Grande de Chiloé and marginally in adjacent border areas of extreme south-west Argentina. Guiñas are strongly associated with dense, temperate rainforest and southern beech forest, particularly the distinctive Valdivian forests in southern Chile characterised by dense colihue bamboo thickets and fern understorey; in central Chile, they occur mostly in Chilean matorral habitat made up of temperate forest, woodland and dense scrub. They occur in suitable habitat from sea level to the treeline at 1,900–2,500m. Guiñas consistently avoid open land such as cultivation and areas with short vegetation except for very small patches, which they traverse to reach cover. They inhabit secondary forest, forested ravines and coastal forest strips in heavily altered habitat, and they use small forest fragments and plantations, for example of eucalyptus and pine, when close to native forested habitat, and provided it contains dense understorey.

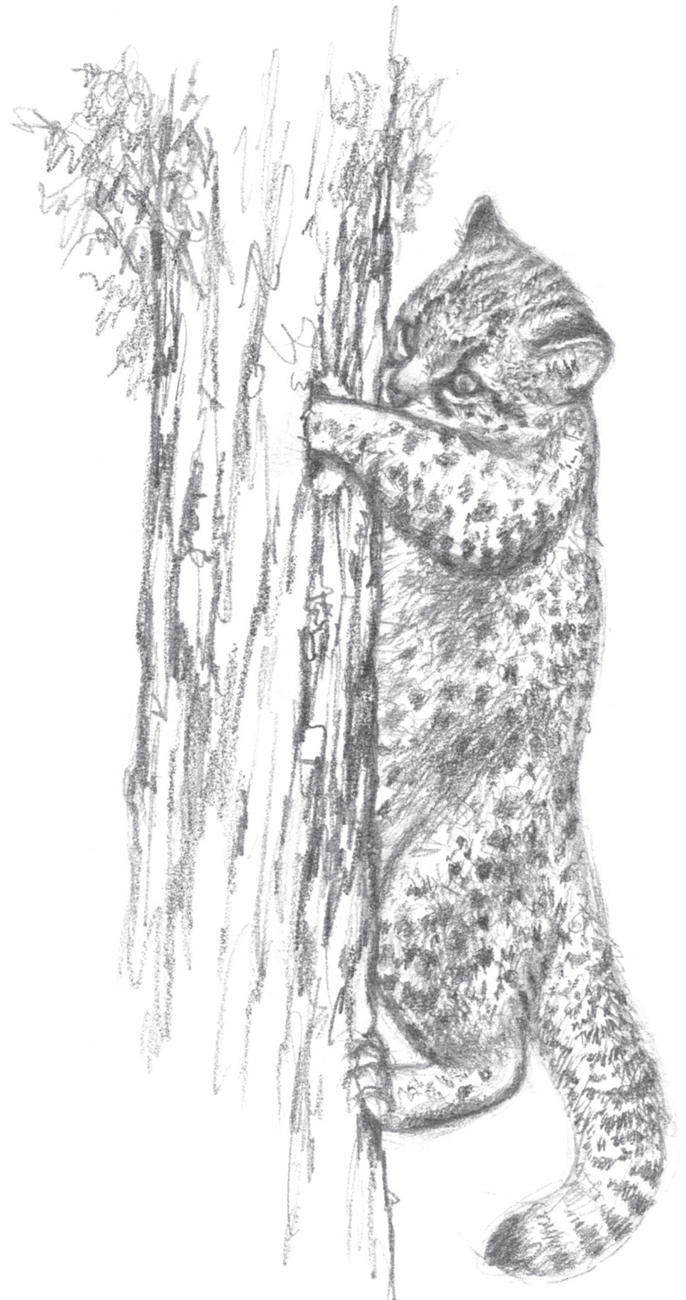

A wild Guiña in Valdivian rainforest of the La Araucanía region in southern Chile. This is the slightly smaller and more richly coloured southern form, L. g. guigna.

Feeding ecology

Guiñas hunt mainly very small rodents especially Olive Grass Mice, Long-haired Grass Mice, Chilean Climbing Mice and Long-tailed Pygmy Rice Rats; very small marsupials (e.g. the 16–42g Monito del Monte); and adult and nestling birds, especially of ‘flutterers’ (near-flightless species) such as Chucao Tapaculos and huet-huets, and ground-foraging or nesting species such as Thorn-tailed Rayaditos, Austral Thrushes and Southern Lapwings. Small reptiles and insects are also consumed, though they probably contribute relatively little to intake. They kill domestic chickens and geese in fragmented, human-dominated landscapes (e.g. on Chiloé), especially where poultry is free-ranging but also by raiding hen houses; domestic goose is the largest known prey species, though they are not recorded preying on comparatively sized wild bird species. Reports by local people of the species killing goats and hunting in groups numbering up to 20 are implausible.

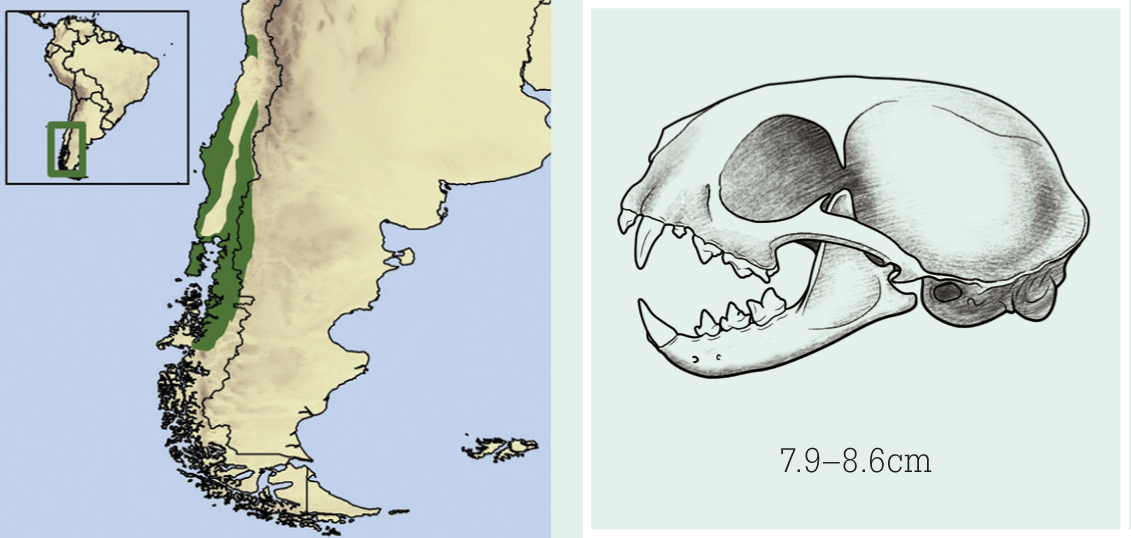

Foraging appears to be cathemeral with a tendency to be most active at dusk into the evening. Hunting mostly takes place on the ground and into the lower understorey in areas of very dense undergrowth where small mammals and birds are most common. They are capable climbers and actively hunt in lower branches. They have been seen stalking small lizards in trees growing in steep-sided ravines and have recently been photographed raiding artificial nest-boxes in trees (up to 1.5m) used by cavity-nesting birds and small mammals. Nest-predation is probably an important source of prey for this species. Although fish has not been recorded in the diet, they readily swim and a young male was observed unsuccessfully attempting to catch fish in tidal pools for 10 minutes; it is likely that fish and marine invertebrates are occasionally eaten. Guiñas are known to scavenge, for example from Pudú and sheep carcasses, though the availability of large carrion in their environment is limited.

Monitoring of artificial nest-boxes has revealed the ability of the Guiña to fish for nestlings, behaviour which almost certainly extends to natural tree hollows.

A Guiña pauses on a tarred tourist road in Parque Nacional Puyehue, Chile. Road construction is a factor contributing to the larger, pervasive threat of habitat fragmentation, which has led to many Guiña populations being isolated in forest islands.

Social and spatial behaviour

Guiñas are essentially solitary and appear to establish small, stable home ranges, but range overlap between adults and independent subadults can be considerable. During a 3.5-year study of two protected populations (Laguna San Rafael and Queulat national parks) in southern Chile, all radio-collared individuals overlapped extensively with all their neighbours. Shared use included the core areas of ranges with very little evidence of territorial behaviour. Aggressive interactions appear to be rare and mild. In the same study, only two aggressive encounters were observed, both between male pairs which were resolved without injury; in both cases, the younger male remained in the vicinity, suggesting fights do not play a strong role in evicting same-sexed rivals from territories, as occurs in many other felids. Territoriality may be more prevalent among populations on Chiloé where core areas were somewhat more exclusive for a small number of adults, and there was limited evidence of two adult males patrolling their range boundaries with constant loud vocalising at the borders. The Chiloé cats live in anthropogenically modified habitat in which the availability of prey may be more limited, leading to greater territoriality.

In protected populations, range size is similar for males and females, averaging 2.4 km2 (females) and 2.9km2 (males). Females in fragmented habitat have somewhat smaller ranges than males, though this is based on a very small number of animals; for example, 0.6km–1. 7km2 for females, compared to 1.6–3.7km2 for males on Chiloé; and 1.2–3.2km2 for females compared to 2.3–4.8km2 for males in human-modified habitat in the Araucanía region. In a 24-hour period, Guiñas may travel up to 9km, with no differences between the sexes, on average 4.5km for females, compared to 4.2km for males. Density estimates from radio-telemetry counting adults and subadults are high: 1−3.3 cats per km2.

Reproduction and demography

This is largely unknown from the wild. Guiñas experience very cold winters which possibly drives seasonal breeding, though this is poorly known. Based on the estimated age of a small number of captured kittens in southern Chile, a possible mating season period occurs in the early spring, August to September, with births in late October to early November. In captivity, gestation is 72−78 days and litter size is one to three.

Mortality Poorly known. The Puma is the largest potential predator, though they are rare or transient in most of the Guiña’s current range. The large Culpeo Fox is a potential predator of kittens. Where studied, people and their dogs are the main cause of death, for example two of seven radio-collared cats on Chiloé.

Lifespan Unknown in the wild, 11 years in captivity.

STATUS AND THREATS

Guiñas have a very restricted distribution (about 300,000km2) and are closely tied to unique, dense temperate forest habitat that is highly threatened. Clearing of forest for agriculture and plantations has reduced Guiña range to many small, fragmented populations. Fragmentation is severe in central Chile where there are an estimated 24 isolated subpopulations, 90 per cent of which contain fewer than 70 individuals. Southern Chile is more of a stronghold, with lower human densities and several large, protected areas with Guiña populations. Guiñas are widely persecuted as poultry pests, though actual damage appears to be less than believed; for example, only 4.5 per cent of 199 chicken owners interviewed in the Araucanía region reported losses to Guiñas in the preceding year (2011). Nonetheless, they are readily killed illegally by local people, facilitated by their habit of fleeing to trees when pursued. They are also killed incidentally during legal fox hunts by people using dogs and traps. Due to their small size and relatively drab fur, Guiñas have never been especially targeted for their skins.

CITES Appendix I. Red List: Vulnerable. Population trend: Decreasing.