Andean Cat

Leopardus jacobita (Cornalia, 1865)

Andean Mountain Cat

IUCN RED LIST (2008): Endangered

IUCN RED LIST (2008): Endangered

Head-body length 57.7−85cm

Tail 41−48cm

Weight 4.0kg (single ♂)

Taxonomy and phylogeny

The Andean Cat was formerly classified in its own genus Oreailurus, but genetic analysis places it firmly in the Leopardus lineage. Its closest relative is thought to be the Colocolo but the evidence is equivocal and further research is needed. No subspecies are described but recent genetic analysis shows the southernmost population in Patagonia is an evolutionarily significant unit distinct from other populations.

Description

The Andean Cat is about the size of a very large domestic cat with a stocky build, thickset limbs and large paws. The face is lightly marked, with the exception of broad dark eye stripes running under the temples, and dark cheek stripes. The face has a distinct, slightly anxious expression. The tail is long with very thick fur giving it a bushy, tubular appearance. The thick fur is pale silver-grey marked with large russet blotches on the body that darken to rich grey-brown on the face, chest and limbs. The tail

has 5–10 distinctive thick russet bands that become paired dark brown rings, often with a russet-brown centre, towards the tip.

Similar species The Andean Cat is easily confused with the ‘colocolo’ form of the Colocolo, which is sympatric over most of the Andean Cat’s range. The Colocolo is generally more heavily marked, lacks the distinct long, bushy tail of the Andean Cat and has a pink or reddish nose compared to the Andean Cat’s dark nose.

Distribution and habitat

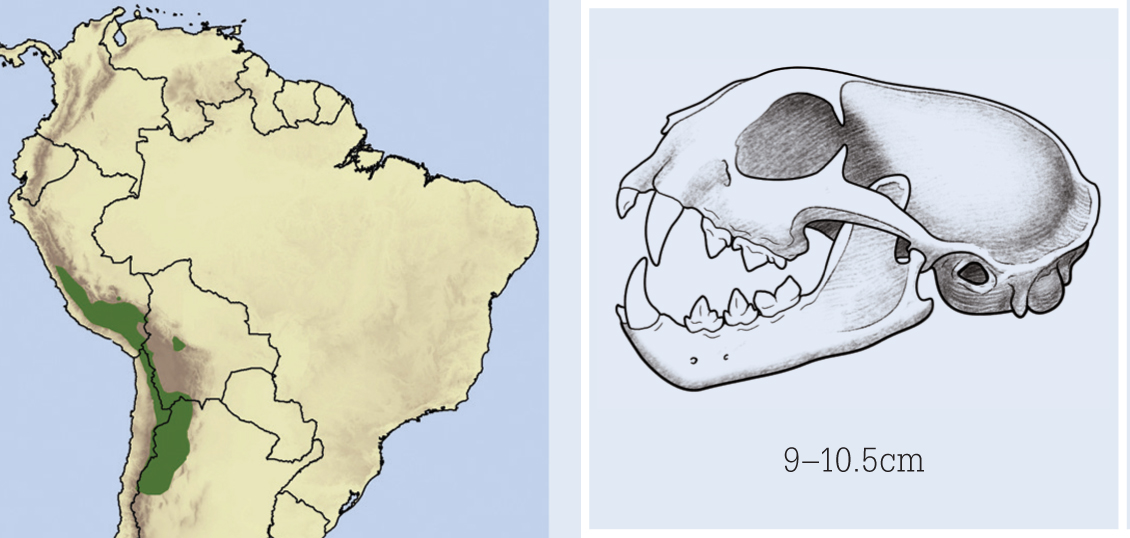

The Andean Cat occurs in central and southern Peru, western Bolivia, north-east Chile and western Argentina, where it has a very restricted range in high Andean habitats mostly from 3,000 to 5,100m, with most records above 4,000m. In the Andes, they are restricted to semi-arid to arid sparsely vegetated areas above the timber-line, primarily in habitats dominated by rocky steep slopes with bofedales (well-watered shrub-grasslands supplied by glacial melt water) and associated dry scrublands. Andean Cats have also been recently recorded from Patagonian steppe in south-west Argentina at elevations of 650−1,800m; this is below the tree-line, in rocky areas with scrub and steppe vegetation.

A female Andean Cat and her kitten photographed by camera-trap on the Chilean High Plateau. Kittens are often slightly darker and more richly coloured than adults, giving young animals a stronger resemblance to the Colocolo.

Mountain viscachas and very small rodents make up most of the Andean Cat’s diet. Andean Cats often consume many more mice than anything else, but at 25 times a mouse's weight, the viscacha is essential for the cat’s survival.

A wild Andean Cat searches for prey along arid, salty lake shore habitat at the Salar de Surire Natural Monument in the Chilean Andes.

Feeding ecology

The Andean Cat is highly dependent on mid-sized rodents living in rocky habitats. Its range overlaps the former distribution of the Short-tailed Chinchilla, which was probably a key prey species but is now reduced to a few tiny, Critically Endangered populations due to overhunting for fur. Andean Cats now specialise largely on two species of mountain viscachas (Lagidium spp.) that also share a very similar distribution. Mice, chinchilla rats, cavies, European Hares and tinamous are also important prey. They sometimes scavenge from carcasses of dead ungulates. Their impact on domestic species is poorly known. There is little evidence for them taking domestic poultry, which are rarely kept in most Andean Cat habitat. Small stock herders in Argentinean Patagonia give compelling eyewitness accounts of them taking down very young goat kids.

Based on limited camera-trapping and one female that was briefly radio-collared, Andean Cats appear to be mostly nocturnal with crepuscular activity peaks. Dusk and dawn are probably important hunting periods to coincide with activity peaks of viscachas. Sightings and activity data from telemetry during the day suggest some flexibility in foraging patterns. Andean Cats rarely occur in anything other than poorly vegetated habitats, and their foraging is ground-based, typically in very uneven, rocky habitat in which they are adept at hunting at high speed.

Social and spatial behaviour

Poorly known. Most sightings and camera-trap records indicate largely solitary behaviour. Only six animals have ever been radio-collared, and data from only one animal, a female in the Bolivian Andes, has been published. She was studied for seven months, and her home range was estimated at 65.5km2, which is unexpectedly large. Preliminary data from five collared cats in the Argentinean Andes suggest comparably large range sizes averaging 58.5km2, which is twice the size of Colocolo ranges in the same area. The Andean Cat’s large home ranges may reflect the species’ reliance on viscachas that live in widely spaced colonies, so that cats may need to cover large distances moving from colony to colony. Andean Cats are always less abundant in camera-trap surveys than the closely related Colocolo where the two species are sympatric. The only rigorous density estimate for Andean Cats is from the Argentinean High Andes where they were estimated at 7−12 cats per 100km2compared to 74−79 Colocolos per 100km2.

Recent surveys and occasional sightings by wildlife photographers have expanded the known range of the Andean Cat. Even with this, its total distribution is very limited and it is not common anywhere.

Reproduction and demography

This is largely unknown from the wild. Andean Cats experience very cold winters that are likely to drive seasonal breeding. The southern spring and summer from October to March is the probable breeding period and would coincide with the birth flushes of many prey species. Kittens have been observed between October and April. The gestation period is unknown but thought to be approximately 60 days, and litters are thought to number one to two kittens. There are no Andean Cats in captivity.

Mortality Poorly known. The Puma is the largest potential predator – they are rare or transient in much of the Andean Cat’s range but abundant in the southern half of their range. Where studied, people and their dogs are the main cause of death.

Lifespan Unknown.

The Andean Cat has very low genetic diversity, comparable to cat species which have undergone population bottlenecks such as the Iberian Lynx and Cheetah. It is suggested that Andean Cats may have undergone similar declines during warm, interglacial periods when suitable high-altitude habitat receded.

STATUS AND THREATS

Andean Cat status is difficult to assess. During surveys, this species is found far less often than other carnivores suggesting it is naturally rare. They have a very restricted distribution and narrow habitat preference that is vulnerable to livestock grazing, agriculture, and mining and oil development, which often affect rocky habitats and water sources. Habitat conversion may also impact prey numbers, especially combined with human hunting of prey species, particularly viscachas, which is considered a serious threat. Andean Cats are sacred according to indigenous Aymara and Quechua ‘harvest festival’ traditions in which the skin or stuffed cat is kept in the house in the belief it confers fertility and productivity on domestic livestock and crops. They apparently have little fear of people and are very approachable when seen. They are easily killed by local people who simply stone them with a large rock. They are also persecuted for suspected poultry and livestock killing and are readily killed by goat-herders and their dogs in Patagonia, Argentina. Rapid and extensive development of ‘fracking’ in Argentina’s northern Patagonian steppe threatens the entire Argentinean Patagonian range of the species.

CITES Appendix I. Red List: Endangered. Population trend: Decreasing.