Leopard

Panthera pardus (Linnaeus, 1758)

Panther

IUCN RED LIST (2008):

Near Threatened (global)

Near Threatened (global)

Endangered (Sri Lankan Leopard, Persian Leopard)

Endangered (Sri Lankan Leopard, Persian Leopard)

Critically Endangered (Javan Leopard,Arabian Leopard, Amur Leopard)

Critically Endangered (Javan Leopard,Arabian Leopard, Amur Leopard)

Head-body length ♀ 95−123cm, ♂ 91−191cm

Tail 51−101cm

Shoulder height 55−82cm

Weight ♀ 17.0−42.0kg, ♂ 20.0−90.0kg

Taxonomy and phylogeny

The Leopard is one of the ‘big cats’ in the genus Panthera and is most closely related to the Lion and Jaguar. Molecular analyses suggest one subspecies in Africa (African Leopard P. p. pardus) and eight Asian subspecies, though an up-to-date, comprehensive analysis is long overdue – Arabian Leopard P. p. nimr (Middle East), Persian Leopard P. p. saxicolor (central Asia), Indian Leopard P. p. fusca (Indian sub continent), Sri Lankan Leopard P. p. kotiya (Sri Lanka), Indochinese Leopard P. p. delacouri (South-east Asia to southern China), Javan Leopard P. p. melas (Java), North Chinese Leopard P. p. japonensis (northern China) and Amur Leopard P. p. orientalis (north-eastern China and Russian Far East). There is recent evidence that fusca, kotiya and western populations of delacouri represent the same subspecies, and similarly for eastern delacouri, japonensis and orientalis, which would reduce the number of Asian subspecies to five.

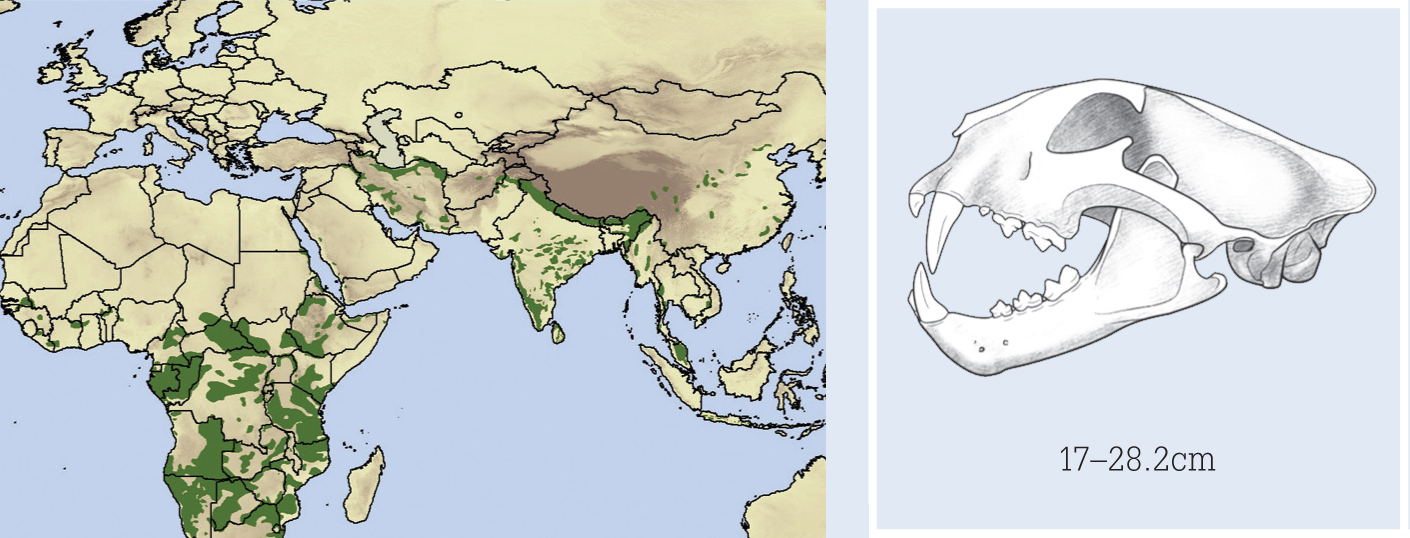

Relative to smaller felids, the front of the skull in large cats like the Leopard is enlarged, with elongated, massive jaws and their associated musculature to deal with large prey.

Melanistic Leopards are spotted just like their normal-coloured counterparts but the spots are only visible under oblique light. Biologists have discovered that infrared camera-trap photography reveals the spots, allowing black individuals to be identified by their unique coat pattern,

Description

The Leopard is a large, robust cat with very muscular forequarters, slender hindquarters and a long tail around two-thirds of head–body length. The head and neck are heavily built, especially in adult males, which also often develop a distinctive throat dewlap by the time they reach five years old. The Leopard’s body size varies widely and correlates with changes in climate and prey availability. The smallest Leopards, from arid mountainous areas in the Middle East, are about half the weight of African savanna-woodland individuals. Leopards from an isolated population in the coastal Cape Fold Mountains, South Africa, are also very small, averaging 21kg (females) to 31kg (males). The largest Leopards are recorded from East and southern African woodlands, and central Asian temperate forest.

The Leopard’s background colour is highly variable, including various shades of creamy yellow, buff-grey, ochre, orange, tawny-brown and dark rufous-brown. The underparts are creamy to bright white. The body is covered with densely packed rosettes, each a cluster of small, black spots around a normally unspotted centre that is slightly darker than the body colour. The spots become large solid blotches on the lower limbs, belly, tail and throat, often merging into a distinctive yoke on the chest. The overall colour is broadly associated with region and climate, paler in arid and temperate areas, and darker in dense habitat and more tropical areas. Melanism is an inherited recessive trait which occurs widely, usually associated with humid subtropical, tropical and montane forests, and occasionally from drier woodland habitats (e.g. Laikipia Plateau, central Kenya). Melanistic individuals (‘black panthers’) are most common in tropical southern Asian populations, especially in Malaysia and Java. Surveys of Ujung Kulon National Park, Java, in 2000–2003 gathered 40 melanistic and 69 spotted Leopard photographs. Melanistic individuals accounted for 445 of 474 Leopard camera-trap photographs from across Peninsular Malaysia and southern Thailand. All Leopards photographed south of the Kra Isthmus were melanistic, although spotted individuals occasionally occur. In Africa, melanism is mostly associated with montane forest refugia (e.g. Aberdare Mountains and Mount Kenya, Kenya; Virunga Mountains, East Africa; and Harenna Forest, Ethiopia) and not the Congo Basin rainforest as widely assumed. Erythristic and albino individuals are occasionally recorded, as is wide variation in spotting ranging from overall diminution to give a peppered or freckled appearance, to extensive marbling and coalescing of the spots (pseudomelanism or abundism) similar to the King Cheetah (here).

Similar species The Leopard closely resembles the Jaguar but they are not sympatric in the wild; apart from a larger, much heavier overall appearance, Jaguars have large, blocky rosettes with internal spots rarely found in Leopards. The Cheetah is roughly similar in overall size and colouration to the Leopard but the two should not be confused.

Distribution and habitat

The Leopard has the largest distribution of all wild cats. It is widely but patchily distributed in southern, East and Central Africa, rare in West Africa and relict or extinct in North Africa. It is largely relict or extinct in Turkey, Georgia, Azerbaijan and the Arabian Peninsula; the most viable populations inhabit the Dhofar Mountains, Oman, and Wada’a Mountains, Yemen. In central Asia, it is rare and now widely distributed only in Iran at low densities. They occur widely but patchily throughout South and South-east Asia including Sri Lanka and Java (extremely rare) into south-eastern China with an isolated population in East China and the Russian Far East. Leopards naturally never occurred on Bali, Borneo or Sumatra.

Leopards have a very broad habitat tolerance, ranging from Russian deciduous forest with winter lows of -30°C, to deserts with summer highs exceeding 50°C. They reach highest densities in mesic woodland, grassland savanna and subtropical to tropical dry and humid forest. They are fairly common in mountains, temperate forest, shrubland, scrub and semi-desert. They are absent from the open interiors of true desert but they inhabit watercourses and rocky massifs in very arid areas. They tolerate human-modified landscapes provided cover and prey are available, including coffee plantations, fruit orchards and irrigated agricultural landscapes, sometimes densely populated with people such as cropland-dominated valleys in Maharashtra, India. Leopards occur from sea level to 4,200m and are recorded exceptionally up to 5,200m (Himalayas). A dead Leopard was found at 5,638m on Mount Kilimanjaro, Kenya.

These large cubs at play in Ruhuna National Park, Sri Lanka are close to the age at which they will disperse. Like most felids, they will be solitary as adults but not asocial; familiar females and males interact frequently in a complex social system of friendly relationships and rivals to be avoided.

Feeding ecology

The Leopard is renowned for its ability to exploit an extremely wide variety of prey species. In concert with its vast range and very broad habitat tolerance, this results in the Leopard having the most diverse diet of any felid. Counting only mammals weighing more than 1kg, at least 110 species are recorded as prey, and including all vertebrates, i.e. small mammals, birds, herptiles and fish, the total exceeds 200 species. Notwithstanding its very catholic diet, ungulates weighing 15–80kg form the mainstay of Leopard diet, with one to two locally abundant herbivore species making up most of the diet in any given Leopard population; for example, Impala (48–93 per cent of kills) in southern African mesic savannas, Springbok (65 per cent of kills) in dry Kalahari savanna, Nyala (43 per cent of kills) in KwaZulu-Natal dense woodland savanna, Axis Deer (more than 50 per cent of kills) in Sri Lankan dry forest, and Siberian Roe Deer and Sika Deer (more than 50 per cent of kills) in Russian deciduous forest. Other common prey includes Steenboks, duikers, muntjacs, gazelles, Bushpigs and Warthogs; and juveniles of larger or dangerous species such as wildebeest, oryx, Hartebeest, Greater Kudu, Giraffe, Sambar, Gaur, Asiatic Water Buffalo and Wild Boar. Exceptional prey includes very young elephants and rhinos, as well as subadults and adults of very large ungulates; the largest on record is an adult male Eland (approximately 900kg), a testament to the formidable strength of the Leopard. The Leopard’s reputation for preferring primates is exaggerated; primates are most important to African rainforest Leopards where at least 15 species are recorded as prey, but these are still secondary to ungulates. Guenons (genus Cercopithecus), colobus monkeys (genus Colobus), vervets (genus Chlorocebus) and langurs (genus Semnopithecus) are typical primate prey but Leopards occasionally kill various baboon species, Chimpanzees, Bonobos and Lowland Gorillas. Leopards will opportunistically kill anything they can catch or overpower; hyraxes, hares, rodents and birds are often locally important. They are recorded killing very large (up to 4m) African Rock Pythons and Nile Crocodiles up to 2m. Other carnivores are readily killed and sometimes eaten, including adult Spotted Hyaenas, Cheetahs and Lion cubs (rarely); e.g. an adult male killed and hoisted two cubs from the same Lion pride in separate incidents (and was later killed by the same pride; Sabi Sands Game Reserve, South Africa). Cannibalism occurs rarely, typically of cubs killed by males and sometimes of adults killed during intraspecific fights. Leopards prey on livestock, occasionally entering corrals and settlements, and they readily kill domestic dogs. Dogs followed by domestic cats and cattle were the most important prey items (by biomass) for a Leopard population occupying highly modified agricultural habitat in Maharashtra, India; 87 per cent of the diet was made up of domestic animals. Leopards sometimes prey upon people, though habitual man-eaters are very rare.

Leopards forage alone, including mothers with large cubs that are left behind. Most hunts are nocturno-crepuscular; daylight hunts are likely to be opportunistic and are generally less successful. The Leopard is a consummate stalk-ambush hunter that varies hunting strategy according to the prey species and habitat. In open habitat such as in northern Namibia and the Kalahari, most hunts are preceded by careful stalks averaging 29–196m until the Leopard is less than 10m from the target. Long stalks are rare in dense habitats with limited visibility, and sit-and-wait ambush hunting appears to be more common. African rainforest Leopards hide in dense vegetation near monkey groups, presumably waiting for them to move close, or they position themselves where encounters with potential prey are likely; for example, in trailside vegetation along game trails or at fruiting trees that attract primates, duikers and Red River Hogs. Most prey species, especially larger ungulates, are killed by asphyxiation with a throat bite. A suffocating muzzle bite is sometimes used, for example with oversized prey; a 14-month-old female Leopard at Phinda weighing 20kg took 14 minutes to suffocate a mature male Impala (60kg) by this method. Leopards normally quickly dispatch smaller prey by biting the back of the skull or neck.

Estimates of hunting success include 15.6 per cent (open Kalahari savanna), 20.1 per cent (dense woodland savanna, Phinda, South Africa) and 38.1 per cent (open, arid savanna, northern Namibia). Daylight hunts in the Serengeti National Park (Tanzania) are estimated to have a 5–10 per cent success rate. In the southern Kalahari, mothers with cubs have higher success (27.9 per cent) compared with females without cubs (14.5 per cent) and males (13.6 per cent). Kalahari mothers kill more smaller prey than lone females or males but travel less for each kill and they kill more often. Kalahari Leopards make an average of 111 (males) to 243 (females) kills annually. Leopards use their tremendous strength to hoist carcasses into trees to avoid kleptoparasitism, including observations of a young Giraffe (estimated at 91kg) and a month-old Black Rhino. The behaviour is apparently most common in African savanna woodlands, but records exist from throughout the range including separate incidents where kills were hauled in response to the presence of Dholes and a Striped Hyaena in India. Leopards occasionally also cache in caves, burrows and kopjes. Leopards in open habitat seek out dense brush or scrub in which to hide kills, and similarly use dense vegetation on the ground in areas where competition from Lions and Spotted Hyaenas is low. They typically pluck fur or feathers (from large birds) prior to feeding, usually starting at the underbelly or hindlegs. Leopards readily scavenge and appropriate kills from other species including Cheetahs, African Wild Dogs, jackals and hyaenas.

By focusing on large-bodied prey, often their own size or larger and equipped to defend themselves with horns or tusks, large felids risk serious injury. This Sri Lankan Wild Boar repelled the Leopard’s attack, fortunately without injury to the cat.

Social and spatial patterns

Leopards are solitary; adults socialise mainly when mating but males frequently associate amicably with familiar females and cubs, including sharing carcasses. Males are tolerant of cubs belonging to females they have mated. Both sexes maintain enduring territories in which the ranges of males are large and typically overlap one or more, smaller ranges of females. Adults defend a core area against same-sex conspecifics but they tolerate considerable overlap at range edges, using a ‘timeshare’ pattern of mutual avoidance and alternating use of shared areas to avoid conflict. Territorial fights are uncommon, especially between long-term neighbours that are aware of each other. Serious fights are more likely to occur when an immigrant adult moves into an area, or when the balance of power shifts between residents, for example if one is injured. Such fights sometimes result in fatalities in both females and males.

Both sexes demarcate territory and advertise reproductive availability by depositing scent-marks via cheek-rubbing and spraying vegetation, and by depositing scats and scraping the ground with the hindfeet. The Leopard’s most distinctive call, sawing (also called coughing or rasping), carries up to 3km and probably serves the same dual purpose. Leopards can almost certainly recognise familiar individuals by this call although this is yet to be tested. Scent-marks are deposited liberally along frequently used routes including game paths, trails, roads and along territory boundaries. A territorial male Leopard continually followed for 65 minutes on ‘patrol’ in Phinda sprayed 17 times, scraped 6 times and sawed 5 times.

Territory size varies with habitat quality and prey availability, ranging from 5.6km2 (female, Tsavo National Park, Kenya) to 2,750.1km2 (male, southern Kalahari). Mean range size for mesic woodlands, savannas and rainforest averages 9–27km2 (females) and 52–136km2 (males). Ranges are much larger in arid habitats, averaging 188.4km2 (females) and 451.2km2 (males) in northern Namibia, and 488.7km2 (females) and 2,321.5km2 (males) in the Kalahari. A collared male in arid, rocky habitat, central Iran, used 626km2 in 10 months. Leopards reach high densities in well-protected, high-quality habitat. Counting only estimates from protected areas, density varies from 0.5 leopards per 100km2 (Etosha National Park, Namibia) to 1.3 per 100km2 (Kalahari), 3.4 per 100km2 (Manas National Park, India), 11.1 per 100km2 (Phinda–Mkhuze game reserves, South Africa), 13 per 100km2 (tr opical deciduous forest, Mudumalai Tiger Reserve, India) and 16.4 per 100km2 (southern Kruger National Park). In African woodland-savannas, average density under protection (10.5 per 100km2) is almost five times as high as outside protected areas (2.1 per 100km2). Density under strict protection in Gabon rainforest is 12 per 100km2 compared to 4.6 per 100km2 in heavily exploited forest. Amur Leopards occur at approximately 1–1.4 per 100km2 in deciduous forest that is mostly poorly protected (Primorsky Krai, Russia), and Leopards occupying heavily converted and densely populated habitat outside protection in western Maharashtra, India, reach 4.8 per 100km2.

Despite a reputation for hunting in the densest available habitats, Leopards in woodland savannas actually prefer areas with intermediate cover, even when prey is more abundant in dense habitat. Intermediate habitat probably provides the best balance between finding prey and being able to catch it.

The Leopard is the only felid to have evolved the strategy of routinely hauling carcasses into trees to avoid losing them to other carnivores. It might have arisen during the Pleistocene when Leopards shared the landscape with extinct sabre-toothed cats and giant hyaenas in addition to modern competitors like Spotted Hyaenas and Lions.

Reproduction and demography

The Leopard breeds year-round but may exhibit a strong birth pulse negatively associated with the lean season; e.g. twice as many litters are born in north-east South Africa in the wet season (October–March, when seasonally-breeding ungulates give birth) compared to the dry season. This is poorly known in their northern range where extreme winters are likely to give rise to seasonality, e.g. in northern Iran and the Russian Far East. Oestrus lasts 7–14 days, during which females call and scent-mark constantly, and sometimes make long forays outside their territory to find males, e.g. up to 4.7km in Phinda and Mkhuze game reserves (South Africa). Gestation is 90–106 days. One to three cubs are born; litters numbering up to six are recorded in captivity but this is exceedingly rare in the wild, e.g of 253 litters born in Sabi Sands Game Reserve, none exceeded three cubs. Weaning begins around 8–10 weeks and suckling typically ceases before four months. Adoption occurs rarely, and usually between related females, e.g. a 15-year-old female adopted the seven-month-old male cub of her nine-year-old daughter and raised him to independence (Sabi Sands Game Reserve). Inter-litter interval averages 16–25 months. Cubs reach independence typically at 12–18 months; the earliest at which cubs survive is seven to nine months. Female dispersers often inherit part of their mother’s range while males disperse more widely, e.g. 113km (Kalahari) to 162km (north-east Namibia). A male dispersing from Phinda Game Reserve, South Africa, entered southern Mozambique and covered a minimum distance of 356km in 3.5 months, before dying in a wire snare in north-east Swaziland, a straight-line distance of 195km from his natal range. Both sexes are sexually mature at 24–28 months; females first give birth at 33–62 months (Sabi Sands Game Reserve) at an average age of 43 (Phinda) to 46 months (Sabi Sands), and can reproduce to 16 years (19 in captivity). Males first breed around 42–48 months.

Mortality An estimated 50 per cent (Kruger National Park) to 62 per cent (Sabi Sands Game Reserve) of cubs die in the first year. Survival of cubs to independence (18 months) is 37 per cent (Sabi Sands Game Reserve). The leading cause of death in well-studied populations is infanticide by male Leopards which may kill unrelated cubs up to 15 months old; in a well-protected, stable, high-density population in South Africa, infanticide resulted in the deaths of 29 per cent of 280 cubs born between 2000 and 2012 (Sabi Sands Game Reserve). Females aggressively defend cubs from infanticidal males and sometimes succeed in saving cubs but occasionally this can result in the death of the mother. Second to infanticide, most cub deaths are due to interspecific predation, mainly by Lions and less so Spotted Hyaenas in Africa, but not much is known about Asia. Estimates of adult mortality include 18.5 per cent (Kruger National Park) to 25.2 per cent (Phinda). Aside from deaths by people, adults are killed primarily in territorial fights with other Leopards and by other carnivores, especially Lions and Tigers; over 21 months, Tigers killed three adult leopards and two cubs in 7km2 of Chitwan National Park (Nepal) in an area of high Tiger density. Groups of Spotted Hyaenas, African Wild Dogs, Dholes (and perhaps Grey Wolves although there are no observations), Wild Boar and baboons occasionally kill Leopards, usually young or infirm animals; an adult male Leopard in Ruhuna National Park (Sri Lanka) injured by another Leopard was later killed by three Wild Boar adults. Large Nile Crocodiles and African Rock Pythons are recorded rarely preying on Leopards, and there is at least one record each of cubs killed by Chimpanzees, Honey Badger, Martial Eagle and Mozambique Spitting Cobra. Hunting accidents are rare but Leopards occasionally incur fatal injuries from dangerous prey; for example, an adult male died after being gored by a Warthog. Leopards have died from wounds inflicted by crested porcupines in both Africa and Asia, though Leopards frequently kill them and typically recover from embedded spines. Deaths from disease are uncommon in Leopards.

Lifespan Up to 19 (females) and 14 (males) years in the wild, 23 in captivity.

Female Leopards will spend most of their adult lives raising their cubs. One intensively monitored South African female who was observed raising 10 successive litters over a 12-year period was without dependent cubs for only 22 per cent of the time.

The skin of a poached Leopard, confiscated by wildlife authorities in Odzala National Park, Republic of Congo. Despite international trade in spotted cat fur being outlawed decades ago, cat skins are still sought after in some communities and illegal trade is widespread.

STATUS AND THREATS

For a large cat, Leopards are surprisingly tolerant of human activity. They are able to persist close to people and in human-modified habitats where other large carnivores such as Lions, Tigers, Grey Wolves and Spotted Hyaenas have long been extirpated. Even so, the Leopard has been wiped out from large parts of its historical distribution, at least 40 per cent of its African range and more than 50 per cent of its Asian range. The Leopard is common and secure in large parts of southern, East and Central Africa, and widespread but patchily distributed and less secure in much of South and South-east Asia. It is patchily distributed and rare in West Africa; Endangered in Sri Lanka (Sri Lankan Leopard: fewer than 900 remaining) and central Asia (Persian Leopard: 800–1,000 remaining); and Critically Endangered in Russia (Amur Leopard: around 60 remaining), Java (Javan Leopard: fewer than 250 adults remaining) and the Middle East (Arabian Leopard: fewer than 200 remaining).

Loss of habitat and prey is the chief threat, especially compounded by intense persecution in livestock areas and killing by people in human-dominated landscapes; at least one Leopard a week is killed by rural and peri-urban people in India, usually pre-emptively out of fear and occasionally in direct retaliation for killing livestock (or, rarely, humans). The species is heavily hunted in South Asia for skins and parts supplying the Asian medicinal trade, and is killed for skins, canines and claws in West and Central Africa. Bushmeat hunting, especially in tropical forest, competes directly for the Leopard’s principal prey species and may drive extinctions even in intact forest. There is illegal but open trade of Leopard skins by members of the ‘Shembe’ Nazareth Baptist Church in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, for amambatha (shoulder capes). At least 1,000 amambatha, representing a minimum of 500 Leopards, are worn at large Shembe religious gatherings.

CITES Appendix I permitting 12 African countries to export sport-hunting trophies (2013 total quota: 2,648), in addition to small numbers of live animals and skins sold commercially mainly as tourist souvenirs. Red List: Near Threatened (global), Endangered (Sri Lankan Leopard, Persian Leopard), Critically Endangered (Javan Leopard, Arabian Leopard, Amur Leopard). Population trend: Decreasing.