When I woke up the sun was in my eyes, and at first I wasn’t sure where I was; but after a few seconds it dawned on me. I also realized that it was Sunday, and I didn’t have to work; which was rather lucky, since the first sound I heard was the jangling of the parish bells calling people to church, and if it had been a working day I’d have overslept by three hours. We’d both slept at Spintwice’s; and as I lifted my head I saw that I was alone in the big spare bed, with nothing more than a crumpling of the sheet beside me to indicate where Nick had slept. I remembered a few tired murmurs we’d exchanged before we went to sleep, but you couldn’t call it a conversation. I had dropped off in no time at all, the troubled whirling in my head of the recent events and mysteries pacified, at least for a while, by the dwarf’s good nature. For the first time in about a week, I’d had no dreams — or, if I had, I couldn’t remember them when I woke up. Now the sun pasted bright cutouts on the plaster wall, and I sat propped up on one elbow watching Lash, curled at the foot of my bed with his tail under his chin a bit like the dog on the watermark. He twitched, whimpered a brief “Good morning,” and yawned hugely.

I could hear faint voices from another room. I stretched luxuriously under the sheet, staring up at the ceiling where a large fly was revolving in agitation, caught in a spider’s web, buzzing like clockwork. Details and questions began to return, lazily, to my mind.

“Nick,” I said later, as Spintwice served up bacon and bread for breakfast, “I’m going to explore today. Will you come?”

“Explore where?”

I chewed contemplatively. “Not sure,” I said. “Back to the Three Friends, maybe.”

“You’ll have to be careful, in broad daylight,” said Nick.

“I shan’t do anything silly,” I said, a bit impatiently. “Are you going to come?

Spintwice looked from one to the other of us. “I’d rather hoped,” he said, “that Nick might help me with something this morning. I got a box of books the other day and I haven’t had time to look at them or sort them out. I thought you might enjoy giving me a hand.”

This was too much for Nick to resist, of course, and I realized it would be. I promised to come back in the afternoon and tell them what I’d found out; but Lash and I were alone, and swift, as we left the shop and joined the life of the streets. Darting through the narrow lanes of Clerkenwell, we headed towards the City.

After a short time we passed a row of tall, well-kept brick mansion houses with railings outside, the servants’ quarters in the basement, and a short flight of steps up to a grand front door with a hanging basket of flowers above. They were the kind of houses where fashionable doctors and merchants lived. A couple of hopeless beggars, old men in broken hats which opened up at the top like round boxes, were wandering along pestering the servants at the doors. Waiting outside one of the houses was a black carriage drawn by a patient, aristocratic-looking horse.

I stopped and grasped one of the spiked railings. I’d seen this horse and carriage before.

Just to make sure, I crossed the street to take a look at the horse from the other side: and sure enough, along its right flank, there was an unmistakable smooth, long scar.

At that very moment a gentleman in black and grey, with shiny shoes, stepped briskly out of the nearest house and down the steps to the carriage. I didn’t have time to hide, but just had to try and look as inconspicuous as possible on the other side of the road, picking at the leaves on an overhanging tree and hoping he wouldn’t notice me. I watched him carefully. He had a haughty face, his nose held high and his cheeks sucked in, as though there were an off-putting smell beneath his nostrils. There was a low murmur of conversation as he greeted someone who was already in the carriage: the man known as his Lordship, presumably. Someone called an instruction to the driver and, as he lifted the reins, the driver turned his head back towards the carriage window and repeated the address with perfect clarity.

“Fellman’s in the City Road, Milord. Gee up!”

The carriage moved off. I couldn’t believe my luck. Fellman was the name of the crooked papermaker Cramplock had told me about!

My only problem now was keeping track of where they were going. They were moving quickly and smoothly, the carriage black and polished, the red wheels spinning almost silently as it sped along the street. I scampered along the flagstones with Lash beside me, keeping my distance behind the carriage in case I was being watched from the back window; but I soon lost sight of it, and it didn’t take me long to realize I had no chance of catching it up. The road was good and it would be at its destination in just a few minutes. I stopped running.

The air began to smell fresher and fresher as we walked on, the houses around us were newer, and soon there was even a glimpse of open fields and distant green hills between some of the buildings. When we reached the City Road I began looking up and down for signs of the well-dressed man, but well-dressed men were not such a novelty around here, and I knew he wouldn’t have attracted anyone’s attention. I asked a man if he knew where Fellman’s was, and he pointed obligingly up the road in the direction of the Angel. There was no sign, he told me, but Fellman’s mill was well known.

In spite of the Sunday sunshine the buildings here seemed to admit very little light. Two rows of tall, dark-bricked houses formed a forbidding narrow gorge, in which there was scant sign of human activity. As I turned into the street, Lash lingered and started sniffing around by the corner, as though reluctant to swap the sunlight for this chilly gloom. I told him not to be so silly; but I felt goose bumps of sudden cold as, further up the street, I noticed the unmistakable, imposing black carriage of His Lordship, silent and waiting.

I led Lash up the street, quietly, and before we’d got as far as the carriage the strangest smell met my nostrils. On our right was a high brick arch, with a grubby rectangular plate on which I could just make out the three words “High Stile Passage.” Venturing through the arch I found myself in a small, overgrown courtyard, in which the unpleasant smell was stronger still. This was the paper mill all right, though there wasn’t much sign of industry here today: the workshop which stretched along one side of the yard had bars across the windows, with no sign of light or movement inside. Lash trotted over to one corner of the cobbled yard where there was a huge tub with something rotting and smelly in it to keep him amused. A couple of large iron bins stood in another corner, and when I lifted a lid I found a soupy, reeking mess of wet, gluey linen which made me turn up my nose and drop the lid back on with an overloud clang.

To my surprise, when I tried the door of the workshop it yielded with a soft creak.

“Lash!” I whispered sharply.

He came trotting back; and, leaving the door ajar, I tied his lead to a fencepost around the back of the yard, sternly instructing him to stay quiet until I came back outside. He licked his lips and sat down to wait.

The familiar smell of damp paper greeted me as I tiptoed inside. I was in what seemed to be a storeroom, with piles of boxes, shelves full of paper, old sacks, and a big iron bin exactly like the ones outside. I fingered some of the paper on the piles. It was coarse, yellow stuff which looked as though it had been here for years, judging by the thick layer of dust I blew off it. Fellman, it seemed, might be having trouble selling his papers these days. “It’s all done by machine now,” Cramplock never tired of telling me whenever he started a newly opened ream. Lifting a sheet up against the light, I wasn’t surprised to find the familiar sleeping dog shape boldly watermarked.

To my right, through an open door, I could see the workshop with vats and benches and drying frames, and to my left another small door — behind which, as I listened closer, I could hear men’s muffled voices. I couldn’t make out a word that was being said, though there seemed to be more than two people talking in there. As I tiptoed back towards the door, I spotted some unmistakable words, in bold black type, on a scrap of filthy paper beneath my feet.

the Most REMARKABLE CURIOSITYthat Ever was Seen!

CAMILLA

the PRESCIENT ASS

This was what I’d printed myself only the other day! I picked it up — it was definitely one of my posters. How had it come to be here?

Actually, it was half of one of my posters. It had been torn quite cleanly in two, and folded. When I turned it over I found there was writing on the back. And I recognized that as well.

They are closing in. I have lied.

But they already know too much

and they are watching the shop.

Im only warning you.

WHC

I struggled through the crabbed handwriting with difficulty. There was no mistaking it. This had been written by Mr. Cramplock.

But almost as soon as I’d read it, voices and clatters from behind the door suddenly made me jump. Someone was coming! Stuffing the piece of paper into my pocket, I cast about for somewhere to hide. The only place seemed to be the big iron trash can. Jumping inside, I found it had some smelly pieces of old torn sheets in the bottom; but I sank down into them and pulled the lid over me, just in the nick of time.

Through the chink under the lid I could see some men emerging through the door. There were three: the high-nosed gentleman whose carriage I’d followed; then a fat man I’d never seen before, dressed in nasty old clothes; and then — with a sudden tingle of excitement I recognized the man Nick and I had encountered in the Doll’s Head, and whose newspaper we’d stolen!

It looked as though the two of them were preparing to leave; but they were lingering, only a couple of feet away from the bin where I was hiding. I tried my hardest not to breathe.

“This letter explains it all,” the haughty man was saying, in a voice so pompous and drawling that it was difficult to understand.

There was a guttural cough, almost a laugh. “I don’t doubt that it does,” came the reply, “but you knows very well I can’t read it. I just makes the paper, and I leaves it to other people to put whatever they wants onto it, and take whatever they wants off of it.”

“I can’t help worrying it might be a trap,” the third man said. “Word reaches me that little devil’s been seen where he shouldn’t be.”

I felt my skin crawl.

“You mean that whippet of the bosun’s,” came the papermaker’s coarse voice. “He’s everywhere, so they say. But there’ll be plenty of us.” To my horror, he now came right over and leaned on the lid of the bin, his voice resonating just an inch or two from the top of my head. “Boys and bosuns,” he snarled, “is easily disposed of.”

I swallowed hard.

“Don’t worry about the bosun,” said the well-dressed man sharply, “it’s not his sort you need to fear the most.”

“Anyway,” said the third man, “let’s go and pass the message on, and we’ll see you by the Old Tup at nine.”

The Old Tup! It was an inn about halfway between Cramplock’s shop and the prison, even more notorious than the rest of the inns thereabouts for the dishonesty of the customers it attracted.

The haughty man’s voice drawled out again. “I wish you luck, gentlemen. His Lordship and I shall expect to be informed of developments at the earliest opportunity. Good day.” And he left them, presumably to return to the silently waiting carriage, and to His mysterious Lordship sitting patiently inside.

“Are you going to Flethick’s now?” grunted Fellman to the other man.

“I may as well,” came the reply, “it’s just about on my route.”

At this point there was a rhythmic clanging on the side of the can which sent a resonating sizzle through my head. When the man by the can next spoke, his voice was indistinct, as though he’d been tapping out his pipe and had now put it to his mouth to light.

“Just … make sure,” he said through half-closed lips, “you ain’t … followed.”

“Do you take me for a fool, Mr. Fellman?”

“I takes people for fools till I finds ‘em to be otherwise, Mr. Follyfeather.” This caused a slightly tense silence. “Now,” Fellman continued, “if you’ll excuse me, I ‘ave some rags to boil.”

Through the chink in the can lid I saw the other man take his leave; and Fellman watched him from the window for fully two or three minutes, until he was quite sure he’d gone, before going back through the door into the next room.

So! That man we’d met in the Doll’s Head was Mr. Follyfeather from the Customs House. I remembered the name instantly, from the customs document I’d found at Coben and Jiggs’s hideout. But Nick and I plainly hadn’t been as inconspicuous as we’d hoped. I cursed myself, realizing that our every move had probably been watched — even if they’d made the mistake of believing we were actually the same person. These people were a very different kettle of fish from Coben and Jiggs, or from the bosun. Fellman had a streak of coarseness about him, but the other two were obviously wealthy, educated, important people — though no less criminal, it seemed, and somehow even more frightening.

Gingerly, I lifted the can lid and put my head out. Was it safe to sneak away?

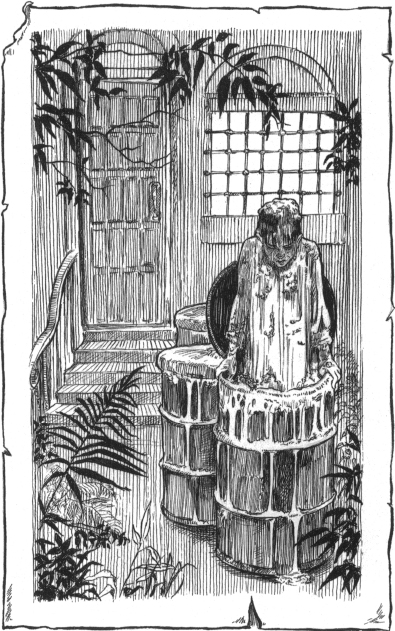

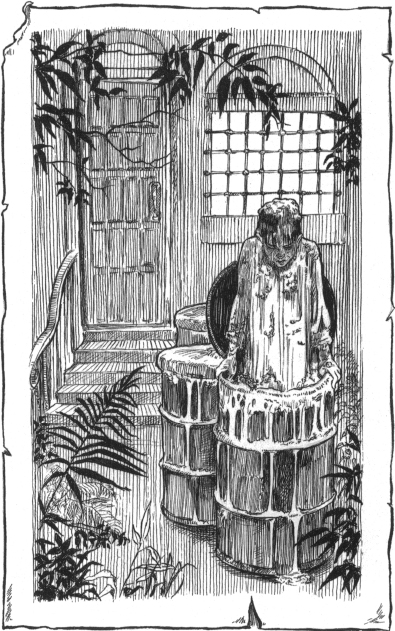

No, it wasn’t. Almost immediately Fellman came back through the door and I sank back into the can. He was heavily built, with skin like dough and patches of sweat darkening his clothes in several places, almost bald except for a few wisps of hair above both ears. Since he’d been speaking to his well-dressed visitors he’d donned a big greasy apron — and he was carrying a bucket. As he approached the can, I scrabbled to push the tatty bits of old sheet over my head to try and cover myself as best I could. I had a horrible feeling I knew what he was about to do. I shut my eyes and held my breath, and just hoped, as I heard him open the can lid above me, that I was hidden well enough.

The next thing I knew, a mass of cold, gooey water came tumbling into the can like flour paste, soaking through my clothes and filling my mouth and eyes. I gasped for breath. Fellman hadn’t seen me: but he’d gone back into the next room for more water, and he was back almost immediately with another bucketful. There was nothing I could do except lie there and let him pour horrible porridgey water all over me again. I could hear him whistling; and as he came back with a third bucket, I began to worry that I might drown.

Nick and Mr. Spintwice, in the meantime, had been rummaging through the old books the dwarf had bought from a barrow for sixpence. Sitting cross-legged on the threadbare carpet, Nick had unwrapped the newspaper parcel they’d been tied up in, blown the dust off each one, and sorted them into two piles, one to keep and the other to throw out.

He and Spintwice had just taken a break for lunch, and begun attacking a plump cheese, when I arrived.

“Don’t laugh,” I told them, as I stalked in. But I was wasting my time. They took one look at me and started to giggle. The gluey stuff I’d got covered in had begun to dry and stiffen in the sun on my way back, and I must have looked rather like a walking statue. Only when the bin had been nearly full of gooey liquid and old rags, and Fellman had yanked it outside into the yard to stand with the others, had I been able to crawl out, retrieve Lash, and escape. I couldn’t bend my legs, and I couldn’t really move my mouth to speak. Lash began yapping, as though he were joining in their laughter.

“You’ve turned to cardboard,” said Nick. “Did you meet a witch?”

“Don’t tell me,” said Spintwice, “a man thought you were a fence, and whitewashed you.”

“It’s all very well laughing,” I said, “I nearly drowned.” As I stood there gradually solidifying, I told them all about Fellman’s mill and the gentlemen visitors, and how I’d had to hide, and what I’d overheard. I was actually feeling quite shaken; but it was difficult to be taken seriously in this state.

“You mean to say you’ve walked through the streets like that?” giggled Nick.

“I didn’t have much choice,” I grumbled.

“Don’t sit down anywhere,” said Spintwice; “I’ll fill a bath.”

He went into the back room and I heard him lighting the stove; a few moments later he returned, dragging a large tin bathtub into the little sitting room.

I began to feel very nervous.

“You really don’t have to bother, Mr. Spintwice,” I said.

“Nonsense,” he said breezily, “what are you going to do, sit there like a statue for the rest of the day? This hot water will see to that sticky plaster in no time, especially if I help scrape it off you once you’re in. We’ll soon have you clean, Mog, you’ll see.”

Nick showed me some of the books they’d been sorting out. I tried my best to seem interested; but my mind was racing, and I couldn’t take my eyes off Spintwice, as he trotted backward and forward for about ten minutes, filling the bath with jugs and pans of hot water.

“Should be just about ready now, Mog,” he said, pouring the last jug of water into the tub.

“I really don’t —” I began; but I didn’t know how to continue. I just stood there, awkwardly. Nick and Spintwice looked up at me expectantly from their armchairs; it was plain they hadn’t the slightest intention of moving.

I looked from one to another of them, helplessly. There really wasn’t a sensible excuse which would get me out of this. I had trusted them both with a lot of secrets by now, I told myself. They were my friends. They deserved to know.

I sat down, took a deep breath, and told them the biggest secret of all.

I could see Nick just didn’t believe me at first.

“No you’re not,” he said, scornfully, as though it were perfectly obvious it wasn’t true.

“I am, Nick,” I said. “I’m a girl. I might look like a boy, and dress like a boy, and talk like a boy, but I’m not one. So now you know, all right? And I’d rather you didn’t spread it around. It sort of suits me that people think I’m a boy. In fact,” I said after a short pause, “I don’t know where I’d be if they didn’t.”

I often thought about this. For one thing, I wouldn’t be working for Cramplock, because girls couldn’t be printers’ devils, and they couldn’t really be apprentices of any sort, come to that. It was only because I looked so much like a boy, and had found it working to my advantage when I was still in the orphanage, that I’d been able to break out of there and make my own way in the world at all. For years now I’d been doing all the things girls weren’t meant to do, like run and whistle and swear — at first because it helped me to keep up the pretense, but after a while just because that was me, and it came naturally.

Being like a girl would be all but impossible, after all this time, probably.

Spintwice’s dumbstruck astonishment had softened, and he was looking at me with something like admiration by now; but Nick was still skeptical. “So Mog’s a girl’s name, is it?” he said.

“Well, it’s —“ I began, and then stopped. I couldn’t bring myself to tell him quite everything, not just yet.

I was named Imogen, after my mother, but I genuinely couldn’t remember ever having been called that. Even in the orphanage I was Mog. I suppose it must have started as a kind of pet name; but as far as I was concerned the two spare bits of my name had just fallen off at either end and been forgotten. “It’s both, isn’t it,” I said in the end. “and it’s, kind of neither, too.”

I watched him considering this. But he was still having trouble with it.

“But you’re not — like a girl,” was all he could say.

“So what are girls like?” I asked him, smiling.

“Well — they’re — well, they’re not much like you,” he muttered eventually, defeated.

“So do you still want to be friends?” I asked him.

“I s’pose.”

“It’s got to be a secret,” I said. “You’re the only people I’ve ever told. Please promise me you’ll keep it.”

Spintwice gabbled his assent, eagerly, and began to apologize; but Nick was still quiet.

“Nick?” said Spintwice, in a tone of reproach.

“I might forget,” said Nick, a bit sullenly.

“Try and remember,” I said.

He looked at me, a smile tugging at the corners of his mouth despite himself.

“It’s just a shock,” he said at last. “Of course I will, Mog.”

I felt a sudden strange elation, as though I’d scored some kind of victory, in a way I can’t really explain. My fingers were working with nervous energy, scratching and kneading Lash’s ears as he sat at my feet, and he was growling with pleasure. He knew, of course, without being told; but I’d never confided in another human being about this. I’d become so used to behaving like a boy that I suppose I half believed I was one, for much of the time. The truth I’d carried around with me for years only mattered when I was alone. Now, at last, I’d found someone I felt I could trust sufficiently to tell; and only now did I realize how much effort it had really taken not to give myself away. It was like having a great burden lifted from my back.

Perhaps — in Nick’s company, and Mr. Spintwice’s — I might be able to feel comfortable behaving like a girl. As it sank in, and I saw the way they both looked at me, and the way their reaction to me had suddenly changed, I couldn’t stop grinning. It made me feel almost as dizzy as the smell of the powder in the camel.

The clothes the dwarf had dug out for me were an appalling fit; and, after I’d had my bath and gotten dressed, with Nick and Mr. Spintwice keeping out of the way in the back parlor, I looked like something out of a traveling circus. But I had to make do with them as I went through to join them for tea and cheese — and at least I was feeling better with all that paste washed off.

They were being incredibly nice to me all of a sudden, all their earlier teasing quite banished.

“How did you two do then?” I asked between mouthfuls, looking around at the piles of books.

“Some of them turned out to be good,” Nick replied.

Chewing, I hitched up my awful pants and crouched in front of the piles of books to look at the spines. “Crimes of the Last Century,” I read, “Being a Catalogue of Misdeeds, featuring most unsavory Murders, Poisonings, Robberies and Waylayings.”

“Thought we might keep that one,” Nick said, almost embarrassed.

I picked up another. “A Booke of Devils. True Hiftories of Wickednesse and Witch-Craft.” Flicking through its fragile pages, I found lots of engravings of sad-faced men being pulled apart by grinning creatures with hooves and pitchforks. “Some of these books are ancient,” I said.

“I know. They’re falling to pieces mostly. There are even one or two in Latin,” said Nick.

But my eye had fallen across something else — and it was more interesting than the books. “Just a minute,” I said. “Nick, have you seen this?” I lifted one of the discarded sheets of newspaper which had been used to wrap the books. “Listen,” I said, excited.

PRECIOUS LANTERN STOLEN

Indian Jewel removed fromShip at Dead of Night

Authorities Baffled

The SUN OF CALCUTTA, a gold lantern worth several thousands of pounds, has been reported stolen from the East Indiaman which bears its name. It had been widely rumored that the ship, lately docked, was bearing items of great value, and the popular intelligence has now been exploited, as was confirmed today by Capt. George Shakeshere. Customs authorities guarding the ship all night expressed incredulity at the loss of the object, which was first found to be missing after a routine search of the ship at dawn. For the East India Company, Mr. Follyfeather spoke of his astonishment and anger. Few eyewitnesses have come forward but a foreign gentleman in a black cloak, seen in the vicinity late last night, is urgently sought.

“I can’t believe I’m seeing this,” I said.

“What is it?” asked Spintwice, holding out his hand for the crumpled sheet of paper. Nick and I just stared at one another while he read it. “I suppose this is the lantern you saw when you went snooping around the ship that time, Mog?” I nodded. “And there’s your man from Calcutta again,” he added as he read further. “I’m getting rather sick of hearing about him.”

“Follyfeather’s got some nerve,” said Nick, “going on about how shocked he is, when he’s really after it himself.”

I was thinking hard. “I bet this is what they were talking about this morning,” I said. “They were making plans to meet tonight at the Old Tup. You know where that is? Near the prison. Just around the corner from the man from Calcutta’s hideout. I bet they’re planning to go round there and look for the lantern.”

“It seems to me,” said Spintwice, “they were asking for trouble leaving a gold lantern on board like that. I mean, you didn’t have any trouble getting aboard, did you, Mog?”

“No,” I said, “but I nearly didn’t get off again.”

“Still,” said the dwarf, “it sounds almost as though it was too easy to steal. As if — someone wanted them to take it.”

“You mean, it might have been left there to trap them?” said Nick, grasping for the dwarf’s logic.

“Perhaps. Of course, it could be that the very people who were meant to be guarding it are the ones who’ve taken it.”

“That makes sense,” I said, “that means Follyfeather.”

Nick suddenly said, “I can think of someone else who could get onboard that ship any time of the day or night.” I looked at him. “My Pa,” he said. “Nobody would challenge him.”

“We’ve got to go to the Old Tup tonight,” I said; “they’re all going to be there. You’ll come with me, won’t you, Nick?”

“Oh dear,” said Spintwice.

“Oh, Mog,” sighed Nick.