Once it was all over, it rained. Big, sooty drops fell through the heavy air, spattering and staining everything in the hot city. It made the worn stones of the streets glisten and sent streams running down their curbs, which swelled out into pools halfway across the road at intervals; it turned the dust of the back lanes into ankle-deep mud; it swelled the black river and submerged the oil-smeared carpet of rags, bottles, and dead animals on the stinking slopes between the water and the embankment walls.

Rumors buzzed around the city like fat black flies. The only certainty was that every story contradicted all the others. Tassie, with her usual air of authority, had assured me that two members of Parliament had been found dead in a basket of snakes, and that the Captain of an East Indiaman had been sentenced to hang from his own mast for the murder of the bosun, who was actually a policeman in disguise.

At work, we were printing any number of news sheets describing the crimes, each of them vying to outsell the others by including more garish and fanciful details; but needless to say none of them seemed to help explain exactly what it was we’d been caught up in, this past couple of weeks. It didn’t take long for word to get around that I had been involved in it all: some versions of the story evidently had me as the hero of the entire episode, judging by the people who stopped by the shop and congratulated me in the first few days. To begin with, I tried to protest.

“I really didn’t do anything,” I told them. “I didn’t catch anybody. I don’t even really know what was happening.” But nobody seemed to believe me, and they pinched my cheek and shook my hand with admiration despite my denials. So in the end I gave up protesting, and just accepted the praise.

“It was a mixture of luck and — well, kind of spying,” I started telling people, bashfully, as they gazed at me with new respect. “But I had a bit of help — here and there.”

After a few days it was impossible to go anywhere without hearing people talking about the printer’s devil who’d foiled a whole gang of villains single-handedly, and I was feeling so important I had almost started to believe it.

“Well I must admit, if I hadn’t been there to witness Coben and Jiggs up to no good at the docks, they’d all have gotten away with it,” I boasted. “And they didn’t bargain for me spying on Fellman when they were laying their wicked plans. Of course, I can’t say too much about it, because Bow Street has sworn me to secrecy on some matters.”

All this celebrity meant that I had very little time to myself for the first few days after it all happened, and I hadn’t had a spare moment to go and see Nick.

Actually, that’s what I told myself; but the real truth was, I was terrified of going. The last time I’d seen him, he’d been furious with me. He’d shouted, and behaved in a way I didn’t know how to explain. After we’d found the bosun’s dead body in the Thames, Cricklebone had sent me home; and I’d left them on the dockside, Nick looking tiny and shaken, with Cricklebone’s arm around his shoulders. I was convinced Nick would simply never want to see me again; that he’d blame me for everything. Despite all my public bravado, I secretly wished that I’d never gotten involved in the first place, that I hadn’t been so nosy, and most of all that I hadn’t dragged Nick into it. We’d been through so much; and something had happened, during that last awful night, to bring us together in a way neither of us could yet quite explain. But I was too scared to confront it, and I was avoiding him.

It must have been almost a week afterwards, and Cramplock had sent me out on my usual errand, delivering things for his customers: a canvas bag loaded with pamphlets, letters, bills. I’d finished the deliveries, and was scuttling back toward Cramplock’s with the empty bag over my head to keep out the worst of the rain. Just as I was within sight of the shop, and was calling out to Lash, who was jumping into puddles with the delight of a small child, I literally bumped into Nick on the street corner, looking utterly bedraggled.

At first we didn’t say anything. I was embarrassed. Suddenly, momentarily, the events of last week seemed like another life. We stood there, getting wet. It was as though we were looking at one another for the first time.

Then Nick said:

“I thought I’d come and find you.”

“I’m sorry I haven’t been,” I managed to say. “We’ve —“ I was about to say we’d been busy in the shop, and then I realized how pathetic it sounded, so I shut up.

Lash came running back when he realized Nick was there, and dug his sopping wet friendly muzzle into Nick’s palm.

“Are you all right?” Nick said, half to me and half to Lash.

“We’re fine,” I said. “Are you?”

He looked up. “I thought you’d abandoned me,” he said quietly, his face streaming with rain.

Lion’s Mane Court had been overrun by officers, looking for evidence and information, stopping everyone who tried to call, taking things away. One of the things they’d taken away, mercifully, was Mrs. Muggerage, who had been arrested and charged with receiving stolen goods, while investigations continued into how much of a part she’d played in the bosun’s various other crimes. Nobody had shown much concern for Nick, and he’d been living at Spintwice’s. He was terrified that if Mrs. Muggerage were freed, he’d have to go back and live with her; in the meantime he was trying not to think about it.

Cramplock was obviously taken aback when I appeared at the door with Nick by my side; but his immediate thought was to help us dry off. In a flutter of kindness, he hustled us in front of the fire in the back room, produced a pile of slightly tattered towels from somewhere, and even poured us hot milky drinks from a newly boiled pan. Lash settled down by the grate and busied himself licking the rainwater out of his fur.

I wrapped one of the towels around my shoulders, and Nick took off his sodden, ragged shirt and laid it across the back of a chair near the fire. Only when we’d gone some way to drying our clothes and flattened hair, and the fire was making our cheeks glow, did Cramplock give voice to his initial surprise.

“You know, when you turned up at the door just now I could have sworn I was seeing double,” he said. “Has anybody ever told you two boys that you’re — that you — why, you could be mistaken for one another.”

Nick shot me a significant glance and I just said:

“One or two people have noticed, Mr. Cramplock, yes.”

He left us, and went through into the shop; and Nick and I began to try and piece together the events of the last few days. Even though we’d been a part of it, we were no more certain than anyone else as to exactly what had been happening. We hadn’t seen Cricklebone, or anyone else who could tell us what was going on, since that morning on the dockside. The more we tried to explain, the more elements there seemed to be which didn’t fit, or didn’t make sense.

The chief villain, it was clear, was the man called His Lordship. He had plainly been using his influence over people such as Follyfeather, in the Custom House, to profit from the smuggling of goods into London. He appeared to have a whole network of thieves operating on his behalf, all of them working for his benefit while seemingly working against each other. People like Flethick and his friends were obviously prepared to pay a lot of money for the powder which they burned and smoked at their strange nighttime gatherings. In turn, they made a tidy profit by selling it to other people.

“It was a load of thugs all trying to outdo each other,” Nick said. “It’s obvious they all wanted to get their hands on the camel, and the powder that was inside it — and the gold lantern.”

I wanted to ask him about the bosun’s part in it all. And how did Nick really feel, now that he was dead? But I was too nervous even to bring him up, and Nick showed no inclination to talk about him.

As far as I remember, in fact, he never mentioned his Pa ever again.

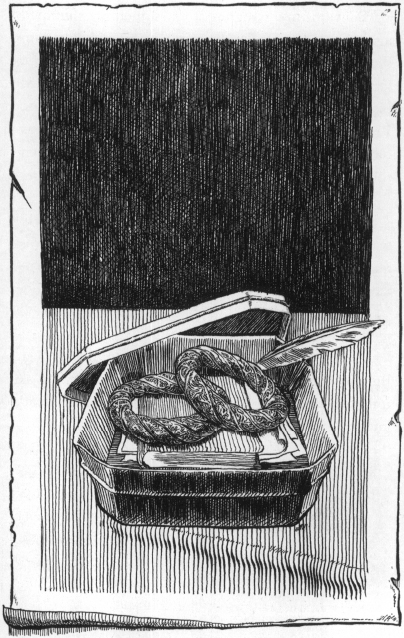

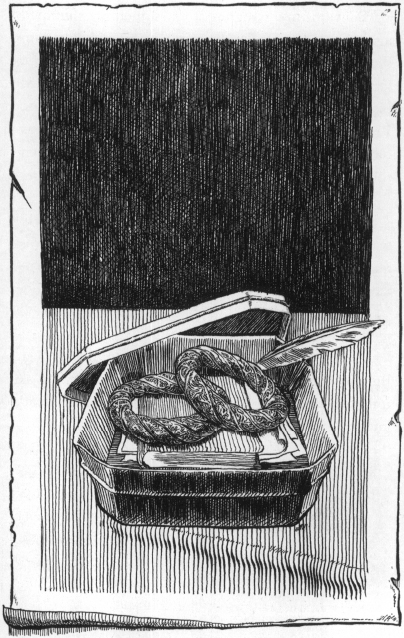

Nick had managed to rescue a few of his own things from the house. Reaching for his ragged shirt hanging by the fire, he dug his fingers into the pocket and, half-apologetically, he held out a bangle.

“I wanted you to see this,” he said.

Even though I knew it wasn’t mine, I couldn’t help being seized by the same suspicion Nick had shown on the dockside that morning. It was absolutely identical: the same size, weight, and color, with the same markings snaking around its whole surface. I don’t think either of us really believed there were two, until I went to fetch my treasure box, took out my bangle, and put his and mine side by side; and it seemed so strange, so unbelievable, that we both just sat there laughing, unable to speak. What did it mean?

I watched him in the firelight, turning the banglesover in his hands, comparing them. Without his shirt, it was clear that he was even browner than I was myself. Where his skin had been continuously exposed to the sunshine, on his forearms and the back of his neck, it shone a rich, deep chocolate color. He was thin, but — as I suddenly realized with a confusing rush of admiration — strong.

I became aware of Mr. Cramplock in the doorway; and it occurred to me he might have been standing there watching us for quite some time. I felt blood rushing to my cheeks, and I shuffled a bit closer to the fire so he might think I was reddening from the heat.

“Would either of you two ruffians like another hot drink?” he asked.

Nick raised his eyebrows. “We both would, Mr. Cramplock,” I said, quickly.

Cramplock had been very quiet as the revelations emerged; and to be honest I was a bit wary of talking about it with him. I still wasn’t sure how much of a part he’d played in it all; but he’d been noticeably better-tempered, these past few days. As he brought in the drinks and handed them to us there was a softness in his eyes, which I’d rarely seen in all the years I’d known him. Without thinking about it, I said:

“Mr. Cramplock, I don’t think I’ve really been telling you the truth these past few weeks.”

He came and sat down, rubbing his cheek intently. “Mog,” he said, “I’m afraid that makes two of us.” He seemed to be finding it difficult to think of the right words. “When you kept asking me questions about watermarks … and when we kept getting threatening notes … I wasn’t really trying to stand in your way.”

“I never thought you were,” I said.

“I thought you suspected me of being in the plot,” he said.

I considered this. “Not exactly, Mr. Cramplock,” I said. “But I knew you knew the men. You knew Fellman the papermaker. And you knew Flethick. And I thought you were maybe — protecting them.”

“I was threatened with death,” he said in a quiet voice, “more than once. I was very frightened, Mog, and if you’d had more sense you would have been too.”

We watched him as he talked, his voice quiet and his face serious in the glow from the fire.

“I got mixed up with that crew years ago,” he said, “and I’ve been trying to get out of their grasp ever since. They wanted me to do printing jobs for them — forgeries and suchlike. Well, once upon a time, I used to. But I knew I could go to prison if I was found out, and it’s not hard to trace the source of printed matter, Mog, as you well know. I started to refuse to work for them. They weren’t very pleased with me. And then when Cockburn broke out of prison they happened to find out I was doing the wanted poster.”

I suddenly realized what had been going on. “You mean you changed the picture deliberately?” I said, my eyes wide.

“I, er — sabotaged it, in a manner of speaking, yes,” he said, looking at the table, “and then I, er — blamed you. Mmmm. It was the only way I could see to stop them beating me to death one night after I left the shop. I had to do something that would satisfy them I was helping.”

I looked at Nick, dumbfounded. He gave a short laugh, a mixture of disbelief and relief.

“Why didn’t you tell someone?” I asked Cramplock.

He looked at me through his little glasses. “You know better than to ask me that,” he said. “Why didn’t you tell someone what you knew? It’s not that simple, Mog. You don’t know who to trust, do you?”

“So the wanted poster went out with the wrong face on, and Cockburn got away without being recognized,” I said.

“For a while, yes. Of course, he couldn’t hide from the criminal types who’d known him for years.”

“You docked my wages,” I reminded him, indignantly.

“Did I? I’m sorry. I must have been getting carried away.”

A thought occurred to me. “Did you write a note to Fellman?” I asked.

“After the poster, yes,” he said. “I decided it had all gotten too dangerous. I wrote to him to warn him this shop was being watched, and that I’d had threatening notes.”

“And you were being threatened by Follyfeather as well,” I said. “I saw a letter …”

“I was being threatened by everybody,” he said. “And then when you started getting threatening notes too, that’s when I got frightened. I thought it was best to pretend I didn’t really understand. But I really started to be careful then — and when a man from Bow Street came to see me, my main concern was to make sure they were looking after you.”

I suddenly had an enormous amount of respect for Cramplock. Here he’d been, stringing along the criminals, trying to persuade them he was on their side, while all along he’d been cooperating with Cricklebone’s men, and watching out for my safety too. I was terribly impressed, and felt rather meek.

There was something else I suddenly realized I ought to ask Cramplock about once again: one of the biggest mysteries of all.

“You know the old house next door,” I said, “you haven’t seen anyone coming and going in the last few weeks, have you?”

“You asked me that before,” he said. “I told you then, it’s not safe for anyone to come and go. Nobody in their right mind would hide out in there. I’m quite sure nobody’s been in there since the fire, all those years ago.”

“No,” I said, “no, I went in there. Last week. I got trapped in there. I meant to tell you, because I fell through the wall and — made a bit of a mess. But he was hiding out there all the time.”

Cramplock was looking at me very strangely indeed. I had lost him completely.

“Who was hiding out?” he asked, baffled.

“Well—” I stopped. This was a trickier question than it seemed. Who was it who’d been hiding out next door? The person who had found me in the chest at Coben and Jiggs’s lair? The person I’d seen in the stable at Lion’s Mane Court? The person who had tied up Mr. Spintwice and taken the camel? The person who had later been left in a lifeless heap at the side of the lane leading down to the docks, on that dreadful night? Or Cricklebone’s colleague, in that ridiculous disguise? Were all of these people really the same person?

Eventually Nick spoke. “You must have dreamt it, Mog,” he said simply.

“No,” I said, indignantly, “I know I didn’t dream it.”

“Well, then you must have been in a different house,” said Nick patiently. “We went in there. You remember what it was like. Anybody could see it hadn’t been lived in for years, Mr. Cramplock’s quite right.”

I bit my lip. He didn’t believe me either. My fingers playing with Lash’s silky ears, I tried to remember how I’d felt, on that hot evening, standing in that mysterious garden and walking around the disorienting old house. “I don’t know,” I said, “but it was as though — when I went into the garden, everything outside it just — stopped existing. As though I was in a completely different place, or a completely different time.”

I was struggling, and they were still looking at me with complete incomprehension. I knew I hadn’t dreamt it, and yet it simply didn’t make sense. Neither the man from Calcutta, nor the man from Calcutta’s house, could possibly be explained. But there was something important about it all; I just had a feeling, because of my dreams, because of the expression I’d seen on his face…

“Nick,” I said, “I want you to look at something.”

Until I got the bangle out, half an hour ago, I hadn’t really looked at the treasures in my tin, since that terrible dawn at the docks. I suppose I hadn’t been thinking straight; because I hadn’t realized that a lot of what I needed to know was folded up inside. But now, with Nick sitting here and the treasure box open beside me, I found my heart was beating faster.

We emptied the tin, and spread its contents out in front of us, pulling Lash out of the way to stop him treading on them or chewing them.

There was Mog’s Book. There were the scrawled notes from the man from Calcutta; pages from newspapers; documents I’d stolen from Coben and Jiggs which we couldn’t really understand, and which they probably hadn’t made head nor tail of either. Only the list of names was missing — kept as evidence, no doubt, by Cricklebone.

And there was the most important document of all: the letter, signed “your undeserving Imogen,” which I’d brought from Coben and Jiggs’s hideout. The letter which Nick had quoted word-for-word, out of the blue, the other night. I held it out to him, half afraid of it, as though it might be infected with some sort of dangerous magic.

“This is it,” I said, quietly.

This was it. He took it from me. “I didn’t even know it had gone,” he said, smoothing the familiar, fragile old paper out carefully. “Coben must have taken it along with the other stuff he stole from our house. He wouldn’t have made any sense of it. We’re lucky he didn’t just burn it or throw it away.”

It was the last page of a letter which, along with the bangle, Nick had owned and treasured all his life. In a fine, fading hand, it covered two sides of a fragile quarto sheet of paper. It was written in a very gracious style, with some long words I didn’t completely understand, and the first part of the letter was long lost: but the point of it was quite clear from what remained. As I read it aloud, Nick joined in, without even looking at the page. He’d read it so many times he knew it by heart.

It began in mid-sentence.

… apart from some doses of physic of Mr. Varley’s which I privately confess have done nothing to improve my condition. Disease is life whence we have come, and despite individual kindnesses the arrangements onboard since we left have been insanitary and unnourishing. Whatever the truth, the Good Lord attends, and it fits us not to question His motives. The one vital duty of my last days remains to be discharged, and it is in pursuit of this, principally, that I have written to you.

You will be surprised and, I fear, aghast, at the request I make of you. Yet I beg you to give this letter your fullest attention, and to consider with the utmost care how you might execute my will. As I have explained, I am delivered of two beautiful children, and in being taken from them I leave them utterly alone and helpless. If I am taken, my sole desire in departing is to know that the warm and desperate little souls to whom my transgression gave life will be spared, and will be able to live, and grow, and laugh, and learn. It is my dying wish that they be cared for, together or separately, in the best circustances which may be afforded, and that every effort be made to bring them up in virtue and health.

I hope I am not mistaken in assuming that you have the means to oversee such an upbringing, and I pray that, with goodwill and modest financial aid, nature may in time be allowed to heal where she has so mercilessly hurt. My dear, I beg you not to —

It continued over the page:

— spurn my entreaty in this matter, much as your first instinct may be to do so. I charge you with this solemn duty not because I wish to burden your remaining years but because I trust you with all my being. Whatever the imminent fate of the soul, it would indeed be too cruel if the still innocent flesh begotten of my misdeed were made to suffer.

I know of nowhere else to turn. I feel so helpless, my dear, and I pray that you will not feel equally so, upon being charged with the care of these precious infants. I would not blame you. Your first instinct may very well be to enlist help, and even to seek out those who are closer to them in blood. Yet I would be in dereliction of my duty if I did not prepare you for the difficulty, perhaps the impossibility, of ever doing so. You would be attempting to conduct your inquiries in a country where letters are rarely answered, and where there are no formal records of people’s names, histories, births, deaths, professions, or whereabouts. I fear it will not be possible to reach Damyata now.

I can say no more; and I am feeling weak. Please God this letter reaches you, and that you do not think too ill of me to grant some mercy to the gentle, perfect creatures who accompany it. My dear, Good-bye, and with all the remaining life in my body, I thank you.

Your underserving,

Imogen

There was a long silence after I’d finished reading it, while the words sank in. The desperate emotion of it, expressed in such measured and refined language: Imogen, it was clear, had been a remarkable woman. I had to blink back tears. Reading these two fragile faded pages had given a personality, a physical presence, to someone who had never existed for me before, except as a name; and I suddenly felt the loss of her like a new bereavement.

I tried to look up at Nick and smile, but my mouth wouldn’t make the right shape, and my eyes were blinded with tears.

“My mother,” I said.

I was afraid he’d think I was silly and girlish for crying. But his face and voice were full of understanding, and I suddenly knew he’d come to exactly the same realization as I had, at exactly the same time.

“Our mother,” he said, gently.

She had come, like the Sun of Calcutta, on a ship from the East Indies, twelve years before; and so had we, her twin children. It was impossible to know from the letter whether we had been born on land, or at sea; but we were still tiny and helpless when we arrived in London, that much was obvious; and we’d been delivered into the hands of a family friend or relative, whose name was lost, and who had plainly been unable to look after us for long. I understood how I had come to be in the orphanage; but how Nick had ended up being claimed by the bosun and Mrs. Muggerage was less clear.

But, as we talked, I became convinced of one thing. The man from Calcutta would have been able to tell us everything. On that dreadful hot night, a few minutes of terrible violence outside the Three Friends had probably robbed us of our only chance of finding out who we really were. He had come to find us; and we had spent the entire time running away. “Must talk,” his note had said. And now it was too late.

I hardly let Nick out of my sight, now. I spent all my free time at Mr. Spintwice’s with him, and he spent quite a lot of every day helping me out in the printing shop. Cramplock seemed genuinely pleased that I had discovered a brother I never knew I had; but not, strangely, especially surprised. He was treating us with noticeable kindness, but he still insisted on hard work, and came over to cluck and chivy us on if he found us talking about the camel adventure instead of getting on with the job. I still couldn’t bring myself to tell him that I was a girl and not a boy, and I had sworn Nick to secrecy. It was too much of a risk. In spite of all that had happened, I was more or less sure he’d still decide a girl couldn’t be a printer’s devil.

We thought we might find out more when, about a week later, Mr. Cricklebone came to see us at Spintwice’s. The dwarf had never had anyone so tall in his house before, and Cricklebone had to bend nearly every joint in his body in order to get through the door. Mr. Spintwice was very polite, but he wore a rather frozen expression throughout the visit, as though he believed people really had no business being so tall, and that, if he were in any sort of power, he’d make it illegal.

Cricklebone had ostensibly come to take down statements from us, gathering evidence to be used against the villains. As it turned out, he was the one who found himself interrogated, as Nick and I showered him with questions from the moment he arrived. He was being very cagey, doing little more than avoiding the subject or tapping the side of his sizeable nose. “There’s too much idle talk in London already,” he said.

“This isn’t idle talk,” Nick said; “we want to know what really happened.”

Cricklebone perched on a chair, sipping tea and trying not to let his gangly elbow stray too far out in case it knocked a clock off Spintwice’s mantelpiece.

“Really,” he said absently, “isn’t a very easy word.” He put down his teacup, and picked up a pencil and a folded sheet of paper, preparing to write down some notes. “Now,” he began, his pencil poised, “perhaps you can —”

“I want to know,” I interrupted him, “what Mr. McAuchinleck was up to. Was he really the man from Calcutta all the time? Was it him hiding out in the house next door all that time? Did he kill Jiggs? Did he really have a snake?”

Cricklebone sat silently for a long time, with the end of the pencil in his mouth. “Mmmm-mm,” he said, at length, and I thought for one ridiculous moment he was going to pretend to have a stammer again. “Mr. McAuchinleck was following the case for a very long time. We discovered that a completely new kind of drug was circulating in London, something more dangerous and more valuable than anything known before. We knew it was coming in from the East Indies, and there was a whole network of criminals involved — but what we didn’t know was just how they were doing it, or who was behind it. So McAuchinleck traveled to and from Calcutta on Captain Shakeshere’s vessel. In, ah — incognito, as it were. To watch.”

“Was this when he was pretending to be Dr. something?” I asked.

“Hamish Lothian, yes.”

“But when he got to London he disguised himself as Damyata?”

“I suppose so.” Cricklebone was being a bit irritating. I think he was enjoying the mystery he was creating. “McAuchinleck dressed up a time or two, left a few notes. But the villains did a lot of work for us. They hated each other so much, all Mr. McAuchinleck had to do was play them off against one another. He scared you once or twice … but then, you shouldn’t have been there in the first place.”

“And this drug was so valuable that the villains were quite prepared to kill each other to get hold of it,” said Spintwice, beginning to understand.

“It’s so valuable,” said Cricklebone, “that even the amount contained in the camel could make somebody very rich. You see — once people take it, they can’t stop taking it. They find they can’t live without it. And they’re perfectly prepared to kill for it, yes.”

“So who killed Jiggs?” I asked again.

“Jiggs — isn’t dead,” he replied, surprisingly. “He’s in Newgate. We arrested him, and then put notices out pretending he’d been found dead, to scare Cockburn and drive him out of hiding. Well, it worked: he got really scared, had to change his hiding place, and had to explain to His Lordship where the camel had gone.”

“What about the lantern? The Sun of Calcutta?”

“We pretended that had been stolen too,” Cricklebone went on. “The villains were just waiting for the moment when they could run off with that. His Lordship wanted Cockburn to get it for him, and we knew either he or the bosun would go for it sooner or later. So we, er — made out that Damyata had got away with it before any of them had a chance.”

“And had he?”

Cricklebone looked uncomfortable. “I’m not sure what you mean,” he mumbled.

“I mean, did the real Damyata get there first?” I said.

There was a short pause while Cricklebone contemplated what he was going to say. “Well, we riled them,” he continued, and it became evident he’d decided he was just going to ignore the question. “I’ve been very impressed with Mr. McAuchinleck’s skills. He had everyone well and truly fooled.”

“But there was someone else, wasn’t there,” I persisted. “There really was a man from Calcutta in London, wasn’t there? It wasn’t Mr. McAuchinleck every time, was it? What about the man we found lying in the lane that night on the way down to the docks?”

Cricklebone twitched, nervously. He made a few helpless little marks on the paper and stared at them, as though they were going to transform themselves magically into the answers to my questions.

“And what about the man who tied me up, and took the camel?” put in Mr. Spintwice. “If that was your friend in disguise, all I can say is he was taking his masquerade a bit too seriously for my liking.”

“And the house next door,” I said. “That night when I went inside, and it was all brand-new. Did McAuchinleck have it rebuilt?”

“He couldn’t have, could he?” Nick put in. “And then torn it all out again two days later? Why would he do that?”

Cricklebone’s mouth opened but no sound came out; so I seized on the silence to tell him about the letter from Imogen; about its reference to the name “Damyata”; about the hunch I’d had that the man from Calcutta had been trying to tell me something important — and hiding out next door all the while. Cricklebone was trying to make his face look as though he already knew every detail of what we were telling him; but behind the stiff expression his eyes were betraying occasional surprise, even alarm, at the mounting list of things he realized he still had to investigate.

“Well,” he said at length, with a frog in his throat, “Certainly it must seem to you as if your man from Calcutta is a — a bit of a magician. I admit there are one or two details of Mr. McAuchinleck’s activities of which I’ve yet to be, ah — fully apprised.” He’d gone a bit pale during my story, and now he was doing his best not to look crestfallen. “I th-think I’ve said enough for today,” he finally muttered.

“What suspense,” remarked Mr. Spintwice, who’d been listening with increasing surprise. “Like finding the last few pages of a book torn out.”

Cricklebone pricked up his ears at the metaphor. “Books,” he said, “as Mog here well knows, tend to have a few blank pages at the end.”

“Yes,” I said, “because usually the gatherings have got to be —”

“It’s because,” Cricklebone interrupted, “the end of a book is very rarely the end of the story” He looked rather pleased with this analogy, and stood up too fast, hitting his head very sharply on the low beam. “Well,” he said, his eyes watering, “Good day.”

We showed him to the door. As he left, he held out his hand rather awkwardly to shake mine, then Nick’s.

“Nick,” he said, “Mog. I mean, Mog. Nick. Whichever one of you is which, ha ha. You’ve ah — you’ve done some good work for us these past few weeks. Remarkable work, though you might not know it. I wouldn’t be too surprised if there were some sort of, er — reward, for this.”

Four pairs of wide eyes looked up at him from the doorway: Nick, Spintwice, Lash, and myself.

“Keep out of mischief now, mmm?” he muttered, finally; and he turned, and was off, like a stick-puppet, into the noise and bustle of the city. We never saw him, or McAuchinleck, again.

They hanged Cockburn in October.

It was like a fairground. Everyone was wearing a happy face, as if it were a holiday. A juggler was entertaining for coins. You could buy poorly printed pamphlets relating the gory and embellished history of Cockburn’s misdemeanors. Mr. Glibstaff was strutting about looking important, tapping people officiously on the backs of their calves when they were standing where he wanted to walk. Above us, every window on either side of the street was flung wide, with four or five cheery people leaning out of each one to enjoy the spectacle.

Nick and I moved among the crowds, with Lash between us. Costermongers had cleared their carts and were charging people a halfpenny to climb up on them for a better view. I saw Bob Smitchin organizing one such grandstand.

He winked at us.

“Grand day for it,” he said. He might have been talking about a picnic. “You’d be a proud feller today, Mog.”

“Proud?” I said. “Why?”

“Well, ‘e’s your convict,” Bob said cheerfully, “people might say you got a particular interest in the case, Mog.”

“Mmmm.”

“Serve ’im right,” he continued, helping another couple of people up onto his already overcrowded and wobbling cart, “way I see it, a feller chooses to be a miscurrant, or not a miscurrant. Should be prepared for the consey-cutives.”

“Anyone would think,” I said to Nick, “it was the Devil himself being hanged.” Pressing our way between the gathering hundreds, Nick and I spotted several people we knew to be thieves, or thugs, and they seemed to be shouting as loud as anyone else, presumably relieved it was someone else going to the gallows this time.

“Some of this lot should be up there with him,” said Nick. He nudged my arm and nodded towards a wily-looking urchin a couple of years older than us who was creeping round a circle of long-coated gentlemen. “Plenty of pockets to pick today.”

“They’ll find nothing on me,” I said, tapping my empty pockets. “That the sort of thing you used to do, is it?”

Nick shrugged.

Since the bosun’s death he didn’t seem to have stolen anything. People used to patronize him and tell him he’d turned over a new leaf, which irritated him. “I haven’t turned over anything,” he maintained; “if I wanted to nail stuff, I would.” But he didn’t seem to. I often reflected that, in the past few months, he seemed a lot older; and he laughed a lot more often.

“And I pray our souls be cleansed,” someone was declaring close by, “and our hands stayed by the fear of the Wrath of God.” It was a shabby-looking man with a few broken teeth, holding out his hands and orating to the pushing crowds around him. “Bless you,” he kept saying, and holding out a crumpled felt hat in which a couple of coins lay. “The Lord,” he said when he saw us, “is ever merciful to the righteous, my boys, and fearful to the wicked. A penny from a pauper is more dear to God than all the riches of a nobleman. A camel may more easily pass through a needle’s eye than a wealthy man enter heaven.”

He must have wondered what lay behind the meaningful glance Nick and I exchanged as we squeezed our way past.

All around us, on posts and hoardings, were multiple copies of a new and arresting poster, which had kept Mr. Cramplock and myself busy for the entirety of an autumn evening last week.

THIS THURSDAY at 2PM SHARP

One of the most Notorious

ROGUES and MURDERERS

of this Century

of this Century

IS TO BE

HANGED

At the Place of Public Execution at

NEWGATE

“You know what Mr. Spintwice says?” said Nick. “There’s no such thing as justice.”

Spintwice had, I knew, made no secret of his scorn at the eagerness of people to gather in a big crowd and watch a man being hanged. “What’s he mean, then?”

“I think he means,” said Nick, “nobody can ever be satisfied. You can’t set things right once they’ve gone wrong, not without turning back time and starting again. Like — hanging someone — it doesn’t undo the crime. People want blood, but when they’ve got it they’re no better off, are they?”

The roaring was getting louder as the anticipation mounted. People were becoming aware that it was nearly the appointed time.

“Do you want to stay and watch?” I asked.

“Not really.”

“Let’s go,” I said, and we began pushing back the way we’d come. I had to keep tugging at Lash’s lead to drag him away from half-chewed apples and discarded bits of pie which people had dropped on the ground.

As we emerged out of the crush, a woman came up to us to try and sell us sweets.

“Sugared oranges,” she cooed, “and cherries and ginger. Treats, my dears, come off the boat from the East Indies.” We peered into her tray and saw little squares and diamonds of sugared fruit, some of it wrapped in rice paper. A heavy, spicy smell was wafting up from the sugar-caked board. Nick reached in and took a square of ginger.

“I want to get you this,” he said, fishing in his pocket for a grubby coin.

The woman moved off, and he handed me the sweet. I unwrapped the thin crinkly paper it was wrapped in and popped the chunk of ginger into my mouth. Just as I was about to throw the paper away, I noticed some blue markings on it.

“Hang on,” I said with my mouth full. Folding out the sticky little sheet, I found it had a printed inscription in faint blue. I stared at it. Slowly, the pale characters sank into my brain.

I looked around. “Where’s the woman?” I asked. We tried to call her back, but she’d blended into the excited crowd, and the people were milling too densely for us to catch her.

We turned and set off again, staying close together. The throng was too intent on what it had come to see; no one paid a scrap of attention to the pair of children, remarkably alike, one of them hanging onto a longlimbed dog, and each of them glancing back and forward occasionally to make sure the other was still there — as though, it having taken so many years for them to find one another, they were now determined not to let the other go.

Up the street, a gate in the prison wall swung open, and a broadly built figure was led up the wooden steps to the back of the cart. Above our heads, the bells of St. Sepulchre’s began the solemn sequence that preceded the striking of two. Gradually, starting from the front, the jeers of the crowd fell silent, and the silence spread all the way along the street, up the hill, as far as the cathedral.