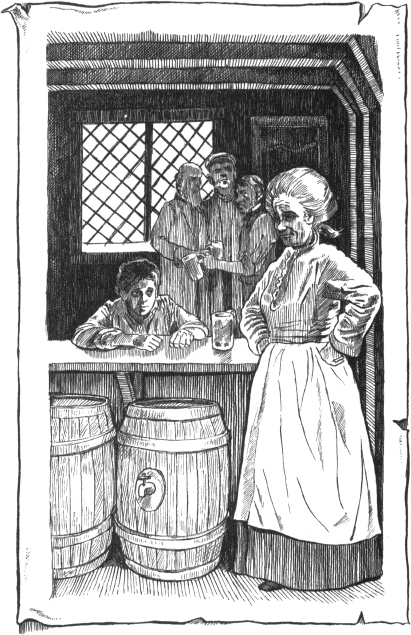

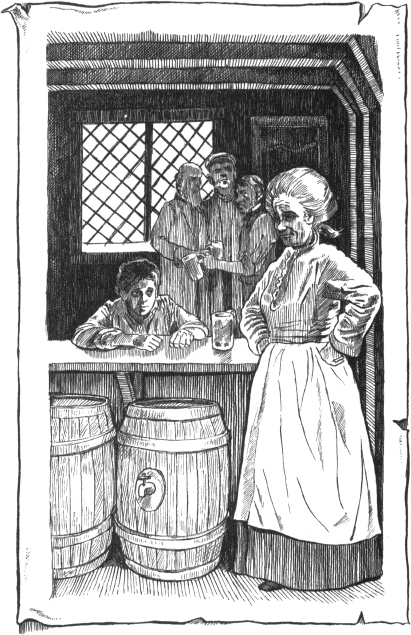

Tassie came through to the taproom of the Doll’s Head, accompanied by a rich tempting smell, and placed a steaming pie in front of me.

“Now, what do you say to that?” she asked, with a grin so broad I could count her back teeth — and there weren’t very many of them.

“Ta,” I said as best I could with my mouth full.

“The lad would eat all I’ve got if I let him,” Tassie cheerfully announced to the rest of the customers, the usual slightly shabby crowd sitting round the tables enjoying a smoke and a Saturday dinner. “Though I’d say he weren’t lookin’ himself today. Looks like he needs some sleep, woul’ncha say, Mr. Gringle?”

The plump bald man at the bar squinted at me critically, and nodded his suet-like head. “Hollow eyes,” he said meaningfully. “In fact, the lad’s got no flesh on him at all.”

“Wouldn’t think he got more of my hot pies down him than any other body in Clerkenwell,” assented Tassie, wiping her taps.

I looked down at the table, irritated. What business was it of theirs? I was jolly glad I didn’t have flesh on me, if it meant looking like Mr. Gringle, whose belly was at present quivering beneath his filthy and bursting waistcoat only inches from my plate. But Tassie was right to say I needed sleep. After my midnight visit to Flethick’s, I’d spent the rest of the night shifting and bouncing in my lumpy bed, and my fitful bursts of sleep had been troubled by dreams of the most disturbing kind.

In my dream I was blundering around in a kind of haze, like the pungent fog of Flethick’s room, in which people’s faces hovered in and out of sight. Some were friendly, others menacing; but in every case, whenever I tried to speak to them, they would be pulled away from me. One shadowy figure who emerged suddenly from the mist turned out to have the face of the convict from the poster. Another turned out to be the mysterious man with the mustache I’d met in the lane: and as he floated towards me, staring with his stark white eyes, his head had seemed to change into that of a crow, his prominent nose becoming a huge black beak before my very eyes.

To tell the truth, I’d had this dream, or something like it, quite regularly since I was tiny. It was so familiar now that, when it started, I always knew what was going to happen, and I dreaded it so much I often tried to wake myself up so I wouldn’t have to have the dream. The part I always hated the most was when Lash’s barking face appeared, and I reached out to try and hug him, and he drifted away, and I tried to grab his lead to pull him back, but I couldn’t get hold of it, and he barked and barked without making a sound, and he was gone.

The final time, just before I woke up, the dream had been especially vivid. A delicate, shining human figure drifted towards me and I found myself gazing into the beautiful face of my mother, whom I had never seen but whose face I always knew instantly in these dreams, encircled by a headscarf of what seemed to be green and gold silk. She was mouthing silent words in the most earnest, imploring way, as though trying to make me understand something terribly important; but, try as I might, I couldn’t make it out. “Ma!” I called to her, “I can’t hear you! Talk to me! Tell me again!” Her lips continued to move but she was receding now, her eyes alive with urgency, calling out to me silently. Real tears welled in my eyes, from frustration and the pain of parting, as I watched her getting further and further away, still calling …

I shuddered. I didn’t dare say a word to the crowd in the Doll’s Head about last night’s expedition: I knew I’d be laughed at, and besides, it didn’t seem quite so serious now, in the light of the next day, with the spring sun overhead and the street outside full of fruit barrows and shouting boys and animals. And I harbored a nagging fear that, the moment I did say anything, dark forces would be lurking and waiting to grab me.

But my mother’s apparition haunted me. I was certain that what she had been trying to tell me was in some way connected with last night’s events. My mind worked feverishly all morning, trying to make sense of what I’d seen and heard. Flethick’s friend had been told to shut up when he talked too freely about something called the Sun of Calcutta. “Such riches!” he had chuckled. They had also seemed especially anxious about someone they thought might have been waiting outside. I was convinced that the stranger I’d met in Cut-Throat Lane must be the person they’d been talking about — the one with three friends — and that he had something to do with the Sun of Calcutta, whatever that was.

Gringle took a sip of his beer, and went over to sit down with some cronies, coughing loudly as he went. I thought it might now be safe to ask Tassie something.

“Tassie,” I said, in a low voice, “where’s Calcutta?”

“Where’s Calcutta?” she echoed loudly, and I winced as her voice pierced the hubbub of the taproom. “Well, er — it’s a foreign place, Maaster Mog.”

“I know it’s a foreign place,” I said, “but where is it?”

Her mouth worked for a couple of seconds with no sound coming out. “Well, er — it’s — a long way off,” she said, and it was obvious she hadn’t a clue. “It’s in, er — the South Pole.” And she seemed satisfied with this sudden piece of inspiration — triumphant, even.

“What are people like there?” I asked her, through a mouthful of pie.

“What are they like?” She echoed again. “Why, they’re — different,” she blustered.

“How, different?”

“Well, they, er. They.” She wiped her taps furiously, as though they were crystal balls and might supply her with the answer. “They probably look like sheep, with curly horns. But I ain’t never seen anyone from there, so I can only say what I’ve heard.”

I decided Tassie was no use at all when it came to geography. But things started to look up almost immediately with the arrival in the inn of Bob Smitchin, a cheerful youth well known in these parts of town. There wasn’t much that went on that he didn’t know about. He always had a winning word for everyone, and usually something extraordinary to sell — which people were better disposed to buy after he’d been nice to them.

“Hello, Mr. Gringle! Mr. Ratchet! Another warm one, eh? Hello, Tom, get the bricks all right? Mornin’, Mr. Fettle. Dot, my love, how was that bacon?Mornin’, Charlie, still on top?” Indeed, wherever he went there were so many people he knew that it was a wonder he ever got anything done at all: he could have spent his entire life greeting people. Once he’d worked his way through the taproom, exchanging handshakes and pleasantries, he came to lean against the bar close to where I was sitting.

“Mog!” he said, noticing me. “The printer’s devil, large as life!” He knelt down to make a fuss of Lash, who sniffed and licked at his fingers happily. “You look like you’ve got something worryin’ you,” said Bob, standing up again. “Nothing amiss, is there? Nobody ill?”

“No, Bob,” I said, “just a bit tired. I was working on posters till late last night.”

“Posters! Not that escaped convict?” he said, giving money to Tassie in return for a full pot of frothy beer she’d just plonked on the counter. “That’s a great job you done on them posters. I seen them up on doors and walls in I don’t know how many places today. What a villain! Murderous! Eh?” He gave a whistle, and then a bright smile.

“I was sick enough of seeing his face after I’d done a hundred of ’em, I can tell you,” I said.

“I’ll bet you was,” he replied, putting the beer to his lips. “Aaah!” he said, after taking a sip. “Tassie’s finest, just the thing to lay the dust.” A slight wince creased his face as the aftertaste hit him. He’d acquired a white mustache from the foam on the beer, and he wiped it away with a stained shirt cuff. “Yeh, that convict poster,” he continued, “what fine big letters, Mog, big bold ones. Not that I knows what they say, but I can tell sure enough they’re big bold words fit to make any citizen watch their step where convicts is concerned. And what a face! What a fine murderous convict’s face to stick up around town. Eh? Only thing is —”

He took another draught of beer, and acquired another frothy mustache in the process. “Only thing is, Mog,” he said again, “I seen that face before.”

“What do you mean, seen it before?” I asked, intrigued. Was he about to tell me he knew where the escaped convict was?

“On another poster. I mean, it’s a fine face, for a villain that is, a fine murderous convict’s face to frighten anyone what lays eyes on it. But it’s the same face what was on another poster for an escaped convict a month or two back.”

I stared at him. “What, exactly the same?” I said.

“No two ways about it, my son,” Bob said cheerily. “Never forgets a fiz, doesn’t Bob, and that one I seen before. Same eyes, same crooked stare. Same big square chin.”

“Well, maybe he’s escaped twice,” I said, “maybe they caught him the first time and locked him up again, and he’s just escaped again.”

Bob shrugged. “Maybe he has,” he said. “Except I feel sure it ain’t more than a fortnight since he did a bit of dancin’ on thin air. The old Paddington frisk? Eh?” He made a strange jerky movement with his body and stuck his tongue out.

I was looking at him blankly.

“They hanged him,” he explained.

“What?” I said, worried now.

“I could have sworn I heard tell,” he said, “that the convict on the other poster was caught and hanged. I could have sworn old Tommy Cacklecross the prison gatekeeper told me that. And if he was hanged, well, they wouldn’t be putting out posters of him saying he’s on the loose, would they? Before you go back and face Cramplock,” he said, leaning closer as if to impart a confidence, “it might be worth you going and having a word with old Tommy, see if he knows the face. He’ll put you right.” And he stood up again, beaming, looking around for someone else to talk to.

“Well, thanks for the advice,” I said crossly. Who was Bob to come criticizing my handiwork, telling me I’d put the wrong face on the poster? If there was anything wrong with Bob it was his habit of putting his oar in where it wasn’t wanted, reckoning he knew more about other people’s jobs than they did themselves. But an uncomfortable dread nagged at me: might I have used the wrong picture? One big ink-covered engraving could look remarkably like another as we fitted them into the blocks in the shop. And Bob’s memory for faces was usually impeccable. What on earth would Cramplock do if it turned out I’d misprinted the poster a hundred times over?

As I ate the rest of my pie I tried to work out where I’d live and what I’d do if I lost my job, and how I’d find enough food to give Lash — and I’d soon constructed an entirely plausible future which saw me sleeping on the cobbles beside the Priory gatehouse covered up in waste-paper I’d stolen from Cramplock’s garbage cans — until suddenly the word “Calcutta” woke me up.

“Yes, Maaster Mog’s quite the mysterious one this morning, ain’t you Maaster Mog?” Tassie was leaning over her bar, chatting to the effusive Bob. “Asking me all sorts of questions about Calcutta and the South Pole, you’d think I was a schoolmaster to be inquired of!”

“Questions about Calcutta?” queried Bob. “Why, that’s a funny thing, Mog, because that’s exactly where this came from.” And he produced from his inside pocket a very large silk handkerchief in an exotic pink and orange pattern, with gold thread running in an ornate trace around the edge. “Thought I might find a likely buyer for this,” he said. “Keep me in beer for the evenin’. Eh?”

“That came from Calcutta?” I asked, intrigued.

“Off an East Indiaman who came home last night,” Bob replied, “straight from the Orient, full of riches to dazzle the worldliest of us! And I can offer this little square of the mystic East —“ he was getting into his stride and waving the handkerchief around at the amused crowd, ”— silk of a quality you never seen, for a song, to the highest bidder. Direct from the hold of the Sun of Calcutta, and unloaded not two hours since. Picture this fine silk softly stroking the neck of a Maharaja’s beautiful daughter.” He put it to his nostrils. “Mmmm! Still richly scented with her heavenly perfume!” There was a ripple of interest among the other customers. He was good at this. “And now, here it is,” he continued, “available to anyone with the wherewithal, to adorn themselves like a true princess!”

But I wasn’t listening to Bob’s eloquent salesmanship. I’d latched onto one specific part of his patter, and I wanted to know more. “The Sun of Calcutta,” I said, “it’s a ship, then, is it?”

“She certainly is, and a finer one you won’t find in the whole port of London,” Bob enthused. “Laden with the gifts of the Orient!”

“Where is it? Where can I find it?”

“Where can you find it?” he repeated. “Where can you find it?” He turned to the little crowd and waved a hand towards me, inviting them to share the joke. “He wants to know where he can find the Sun of Calcutta!” he said, and laughed aloud. “Where d’you find any new-returned East Indiaman, young Mog? In the dock, that’s where — and I don’t mean the kind of dock your escaped convict makes it his habit to stand in!”

Clattering and screeching like the noise of hell itself, the wheels of a hundred carts and carriages mingling with shouting voices and the screaming of wheeling seagulls filled the hot air above the London docks. I fought my way along the riverside, holding tight to Lash’s lead; dodging horses’ hooves, avoiding persistent costermongers trying to get me to buy fruit from their untidily laden barrows; and pushing with difficulty between the heavy coats of gentlemen and tradesmen who thronged the dirty streets. The heat was almost unbearable, the horses whinnying in frustration at the crush. Everyone was sweating. The further I went, the more like a foreign country it seemed, with sailors from overseas laughing and gathering in the doorways of inns and shops, Jewish men in black coats and hats, men carrying things and shouting at the crowd to part and let them through, everyone babbling in foreign languages, arguing and fighting with one another. Every now and again I stopped to ask someone if they knew where I might find the Sun of Calcutta; and every time, if they knew at all, they’d point me further east, towards Wapping and Shadwell.

What Bob had said about Maharajas had made me more sure than ever of the connection between the agitated fellow with the crow’s beak nose, and the Sun of Calcutta. A stranger in London, I told myself, a foreigner lost in the maze of streets the same night as the Sun of Calcutta arrived, must surely have come ashore from that very ship. But the more people I saw as I wandered between the hot, dirty brick buildings, the less convinced I became. How many ships might there be in London just now? And how many countries might they all come from? I realized too that I was venturing into what many people said was the thickest nest of thieves in the world. Most people said so quite importantly, as though it were a matter of national pride that London’s docks should be so notorious. Nevertheless, my curiosity had been aroused, and my progress eastward never halted.

My feet were beginning to ache, though; and I persuaded a passing drayman to let us sit up on his cart next to a few beer barrels. I climbed up first, using the hub of the wheel as a step; Lash bounded up after me in a single leap, with a little yelp of excitement, and sat there with his tongue lolling out, surveying the passing crowds with a superior air from his new vantage point. After a while the drayman pulled up his horse and gestured with a wordless nod of his head down a dark narrow alley leading to the river. We’d arrived. We jumped down and I fished in my pocket for a penny to give him.

The masts of ships jostled for position in the foul-smelling dock, stretching as far as the eye could see. Time and again people shouted at me to get out of the way as they pushed and pulled great cartloads of goods over the cobbles. Dockers and sailors milled in the narrow yards, stripped to the waist, with skins like alligators as a result of years of exposure to salt and rain and scorching foreign sun. We passed huddled little inns: the Galleon, the Sun, the Ship’s Cat, the Crow’s Nest, all playing host to hordes of seagoing men who’d come ashore eager for drink and food and female company. As we got nearer the water, the smell rose and the masts grew higher and higher; loose ropes flapped in the spring breeze, timbers were ranged along the bank for miles, making a noise like the groaning of a thousand wild animals as they bobbed on the water and scraped against one another’s flanks.

Far below, in the dock, I saw a man helping people down into a little wooden boat. Every now and again he shouted up to the crowd on the dockside, “See London by water! Ride on the great Thames! See the City! Room for two more!” The boat was rocking as though it could have done with two fewer, rather than two more, to carry; but the faces grinning up from the cramped little vessel seemed happy enough at the prospect of their trip. The angular man in charge, with a sharp little face like a water rat, looked so untrustworthy I was quite sure the grinning foreigners would soon find themselves robbed once they got out of sight.

I pushed onward, every now and again yanking at Lash’s lead to stop him going after seagulls or some other fascinating distraction. Someone had just pointed out the Sun of Calcutta when I spotted a pair of strange-looking men standing by themselves, eyeing the crowd and whispering to each other. Something about them made me stop and watch. One was tall and very untidy, sturdily built, with a raggy shirt open to reveal a hairy chest and stomach. He had a bandage around his head as though he’d recently been in a fight or an accident. His companion was shorter and skinny; older, it seemed, with a slight stoop. His eyes were grey and lifeless, and his face seemed fixed in an expression of utter weariness, his mouth hanging slightly open, his skin drooping as though it was all being pulled by gravity towards the ground.

I was convinced they were up to no good, from the nervous way they kept looking around. They were making their way towards the mooring where I’d been told the Sun of Calcutta stood; and, keeping my distance, I followed them.

But I didn’t get very far. I found my way blocked by a broad-chested man in a dark coat. “Where do you think you’re going?” he asked. Lash growled, sensing sudden hostility — something he didn’t do very often — and I felt for his collar, both to reassure him and hold him back. I wondered if I should point out the two suspicious types, and turned to look for them — but they’d gone. In that single second I’d let them get out of sight.

“Erm — I’m looking for the Sun of Calcutta,” I said, rather awkwardly.

“Oh yes? And what would you be wanting with her?”

“I’ve, er — come to collect something,” I mumbled, and then wished I hadn’t, because he immediately asked me what. I looked up at him. I couldn’t possibly slip past him, and the determined look on his face didn’t give me much cause for hope that he would let me through. I thought quickly. What on earth might a kid like me want with a ship like that?

“Ink,” I said suddenly. “Indian ink. I’m Mog Winter and I work for Cramplock the printer at Clerkenwell. I was asked to collect Indian ink off the East Indiaman.”

The man bent down and hissed his reply into my face.

“Ink, eh?” he said. “Mog Winter, eh? Winter the Printer.” He showed his teeth.

“Yes,” I said as brightly as I could. “Where can I pick it up?”

“Nowhere,” he hissed. “You show me proof you’s who you says you is. There’s a thousand horrible kids might pretend to work for a printer just so’s they can get on board a ship and snoop around and thieve and do.”

I didn’t have any proof, and I had to tell him so. Lash was still growling softly, and I could feel him tensing beneath my grip. The customs man eyed me suspiciously.

“How much ink?” he wanted to know.

“Twenty-four bottles,” I said confidently. “Big bottles,” I added.

“How you going to carry ’em to Clerkenwell then?”

“Er—” Again I had to think quickly. “I’ve left my cart back there,” I said, gesturing vaguely behind me.

“Really? Then chances are it’ll be gorn when you gets back to it!” The man was rapidly making me feel like a fool. “And I might tell you, for your hinformation, that you can only get your ink on presentation of the necessary monies at the Customs Warehouse, in the City,” he added, stabbing his finger shortly in the direction from which I’d come. “But if you was to let me have something for my trouble, I might just see that nobody else makes off with your master’s ink.”

“Have you seen a man in a bandage?” I asked him, “because there was one over there, and his thin friend, and they looked like they were up to no good.”

It didn’t work. “Could be,” he said, “my brother has a bandage, and a thin friend. Could be a full three-quarters of sailors have a bandage, and a thin friend. And if you don’t want a bandage, to cover up the kick I’m going to give you,” he said in a low voice, “you’d better hook it, Mog Winter.”

This was persuasive enough, and I turned back reluctantly, pulling Lash after me and casting an occasional glance over my shoulder to see if the mysterious pair had resurfaced in the crowd. The more I thought about it, the more certain I became that they were mixed up in the affair Flethick and his sinister friends had been talking about last night. Why else would they be snooping around the Sun of Calcutta, looking so shifty?

Suddenly, there they were again. I edged behind a nearby pile of empty barrels so I could hide and watch them. They were carrying a large decorative chest between them, and were still looking around as if checking to see who was watching them. Then I noticed the Customs man — the same man who’d just turned me away — striding purposefully over to them. The game was up! I was far too far away to hear what was being said — but I was sure they would be in trouble now.

Yet, as the customs man began to talk to them, he didn’t seem at all angry. I could see his face quite clearly, and it was a picture of calm and good humor. He even began to laugh. He was sharing a joke with them! They were making off with a precious chest full of all kinds of exotic treasure, and he was laughing as if it was all a huge joke! But I suddenly understood why when I saw the bandaged one take some large banknotes out of his pocket and pass them quickly to the official. They’d hoped no one had seen the transaction, but they hadn’t reckoned on me watching from behind these smelly, leaky tar barrels.

Only then did I look down at myself, and realize that my hands and clothes were black and sticky from being pressed up against the barrels. Lash, sniffing round them, had acquired jet-black tips to his grey whiskers, and was leaving rings of dark shiny paw-prints as he scampered around me, impatient to be off.

I didn’t have time to worry about my ruined clothes. Right now the most important thing was to follow the two suspicious-looking men. I caught up with them again by the corner of a warehouse, where I saw them talking to a man with a horse and cart. Was he an accomplice, or just a carter they were hiring to carry the load? Dismayed, I watched them all sweating as they lifted the heavy chest up onto the cart. It was going to be much harder to keep up with them now.

I wondered if I should tell someone else. But who could I trust? The customs man, who was meant to prevent this kind of thing, was obviously up to his neck in it. I had a feeling that shouting “Stop, thief!” in a place like this would only make all the thieves laugh.

So, dodging between the people and hiding behind them as I went, I tried to keep up with the ugly pair and their carter companion as they trundled away from the dockside and up the road towards the Galleon Inn, one of the most packed and notorious of the local taverns. Every now and again, I could see them moving ahead of me as the crowd parted. I noticed that the chest had been covered up with a big dark canvas sheet. It could have been anything under there: a chest of drawers, or a couple of ordinary wooden boxes. Nobody even noticed them as they jolted on up the hill.

As the cart reached the Galleon I lost sight of them again. I was running, trying to catch up, when someone pulled my arm.

“Nick!” said a gruff voice, and I turned to see a stocky sailor with a filthy flat cap on his head, his neck blue with tattoos.

“Sorry,” I said, “I’m in a hurry, could you —“

“Not so fast,” he growled, grasping my arm more tightly. “Your Pa’s after your hide. Watcha done?”

I didn’t know what to say. The sailor obviously thought I was someone else. His breath smelled strongly of drink and he was speaking so fast it was all but impossible to understand what he was saying. “I — I think you’ve —“ I began; but he wasn’t listening.

“Your Pa’s up to his neck. He’s three sheets gone and he’s roaring,” he was saying. “Picture of palsy, the man is. Your hide’ll not be worth tanning when he’s roped you in. What’s his rag for, eh?”

“Let me go,” I said, “you’ve got the wrong person.”

“Hang fire then,” he said, grasping me even tighter. “You tell old Samson what your Pa’s rag’s about, and mebbe I let you go. Or mebbe I beef on you, lad. Seems he’s missing summink, and missing it sore.”

“Look, I’ve got to go,” I said, twisting and wriggling in a vain attempt to slip out of his grip.

The man pulled me close to him, violently now, and I caught a powerful hot scent of rum full in the face. Lash barked, but the sailor showed the dog his teeth in a sudden grimace and Lash fell silent, astonished.

“Now you listen,” he said to me, gruffly and quietly. “Your Pa’s in a fine chafe over you, young snaffer, and if I wasn’t so soft I’d run you into that tailshop and let him hang you by your kegs for all to glory over. Now you be warned, chimp, and get yourself out while your molly’s still in one piece, and don’t say I letcha. Hook it!”

I stumbled away, with Lash at my heels, tripping on the cobbles, not daring to look back at the tattooed sailor. What on earth had he been talking about? Furious, I looked up and down the street, but of course the pair of thieves were now nowhere to be seen. Maybe the sailor had stopped me on purpose, to slow me down and let the villains escape?

My eyes stung with sudden tears. Thrusting my hands deep into my pockets, letting Lash follow at his own pace now, I trudged in the direction of home, getting more and more furious about the thieves and the chest I’d watched them taking. As I walked along I realized how strongly I smelt of tar — but when I tried to rub the sticky stuff from my clothes it just made a worse mess than before. I’d have to change when I got back to Clerkenwell.

Suddenly, as I walked past the low doorway of a courtyard, I caught a glimpse of something which made me stop in my tracks. Was it …? I took a step backward and looked through the passageway again; and sure enough, standing against a wall, apparently abandoned, was the cart with the chest on it. I could hardly believe my eyes. They’d just left it here! I whistled for Lash and bent to take hold of his lead again. Keeping him close, I tiptoed up the passageway towards the cart. The nearer I got, the more certain I was it was the same one: I recognized the dark tarpaulin and the shape of the chest beneath it. But surely the villains couldn’t be far away! I had no time to lose. I rushed up to the cart and looked around quickly to make sure no one was watching — then took hold of the cover, and lifted it.

The disappointment was like a hammer blow. An old sideboard! A rotting old piece of useless furniture, with grimy green paint flaking off all over it. This was the villains’ cart all right — but wherever they’d gone, they’d taken the chest with them, and had probably left this here deliberately to throw people off their scent.

It was only then that I noticed a group of children, a bit younger than I was, watching me from a corner of the yard. They had a battered-looking dog with them, which started to yelp when it saw us, and Lash snarled back. The dog looked ill, with milky eyes and a mouth that hung open as though its jaw didn’t work properly. I didn’t want Lash to go near it.

“Did you see the three men who brought this cart?” I asked the children.

None of them said anything. They all just watched me.

“I need to know where they’ve gone,” I said, “the men who brought this. Did you see them? One of them had a bandage on.”

Still they stood, looking dumbstruck. Why weren’t they talking to me? One of them whispered something into the ear of another; and I suddenly realized they weren’t really looking at me, but at something above my head.

I turned too late. Above me there was a scraping sound and, as I looked up, I saw another boy poised on the top of the wall in a crouching position. Just as I noticed the brick he was holding in his hands, he sent it tumbling down towards my upturned face; I remember hearing Lash barking; and the boy’s wild, satisfied little smile was the last thing I saw before the sky seemed to fill with brick, then blood, then darkness.