I had never heard of the Lion’s Mane Inn before, and as I walked home I stopped a few people to ask if they could tell me where it was. I felt somehow drawn to this mysterious bosun; but at the same time I was afraid of him. I couldn’t help remembering the words of the laughing man at Flethick’s, about gizzards — and then there was the earnest advice of the pipe-cleaner man, warning me to keep out of it. But as I thought about it, I realized I couldn’t be sure whether he’d said that out of genuine concern for me, or because he was an accomplice of the bosun’s and didn’t want me poking my nose in.

It had turned into another roasting hot day and some boys were playing round a pump, splashing one another and jumping in and out of the spurting water. I was tired after my morning’s adventures, and the cold water looked very tempting. As I watched the boys my throat felt drier and drier. One of them saw me watching and shouted.

“Come and get wet.”

Shyly, I joined them and stood under the pump while the boy who’d shouted leaned on the handle and made it belch a great cascade of water over my head. It was cool, and a bit smelly, and I shook the water out of my eyes, delighted. Lash ran round the pump, trying to get wet, veering in and out of the splashing water and barking with enjoyment.

There was a big tub underneath the pump, brim-full of water, where people used to take their horses to drink. One of the boys suddenly pulled off all his clothes and jumped into the tub, sending water welling up over the sides and all over the ground. The other boys laughed raucously and ran around him, their feet getting black as the ground around the pump turned to mud. Caught up in the game, I ran too, dodging the squirting of the water pump. The boy was still sitting in the tub and another of the boys was trying to push his head under the water. There were squeals. Two of the other boys pulled off their clothes and tried to haul the first boy out so they could have a turn at sitting in the tub. As I ran round and round the pump, with Lash barking and jumping beside me, I became aware that I was the only one still wearing my clothes.

“Come on,” said one of them, “you come in too.”

I stopped, and watched them grappling and laughing on the edge, skinny and naked, their bodies slippery with the water.

“No,” I said, suddenly, “I’d better go.”

“Aw, come on,” he said, and began tugging at my sleeve. “Not scared of getting wet, are you?”

“No, I —“ I couldn’t explain myself. One of the other boys stood up, dripping, and I was suddenly really scared that they were going to grab me and tear my clothes off for a prank. “No. Let me go,” I said, pulling away.

The first boy stared at me, hostile all of a sudden. “Suit yourself,” he said.

I wrapped Lash’s lead tightly round my wrist. “I’ve got to find the Lion’s Mane Inn,” I said uncomfortably. “Do you know where it is?”

The boy pointed; and gave me a lingering and suspicious stare as I thanked him and walked off, my wet clothes clinging to me, and Lash licking at my wet fingers as we went.

Even after this it took me a while to find the place. The inn nestled in the warren of streets around Christ’s Hospital, between a workhouse and a rather shabby group of broken stables, whose smell convinced me they were still home to living creatures. Peering in, I saw two rather shabby and broken horses, one of whom was coughing alarmingly; and after a few seconds I noticed, with a slight shock, that there was a person in the stable too, sitting on an old box in the corner. It was a grey-haired, filthy old man, slumped in an apparent sleep, looking like a disembodied head on top of a shapeless pile of grey clothing — in fact, he was wrapped in a horse’s blanket. I didn’t dare investigate in case he turned out to be dead.

There seemed to be no one about in the little courtyard of brick buildings adjoining the inn. I could hear a drain trickling, and as I crept round a corner I saw a filthy stream of water dribbling from a pipe in the wall, leaving a spreading patch of brown slime over the brickwork all the way to the ground. A flight of stone steps led up to a door halfway up the house side. This irregular, badly whitewashed yard must be where the fearsome bosun lived.

I decided I’d rather not knock on any doors. Holding tight to Lash’s lead, I peered through the nearest grimy window and could see nothing. The place looked deserted; except that there was a washing-line stretched over an upper balcony, with a gentleman’s breeches and two huge pairs of bloomers hanging on it.

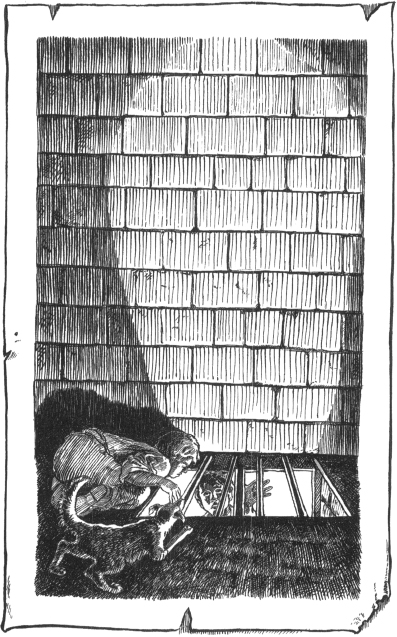

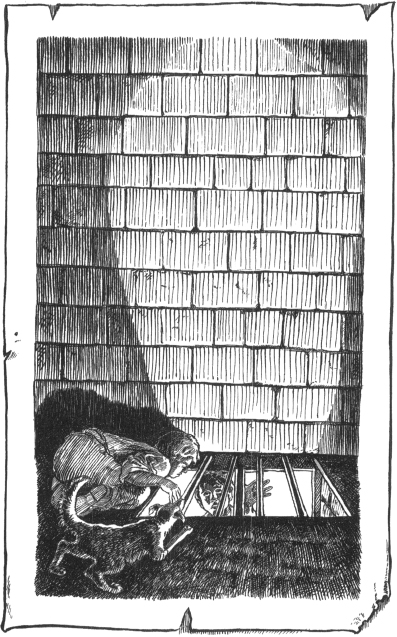

There was a grille in the ground nearby, and as I squatted down to squint through it I could see another grimy little window beneath it, as opaque and unhelpful as the other. I was about to give up, and make my way home, when I thought I saw a face peeping out behind the grille at my feet.

I crouched on all fours now, like a beetle, and peered down. The window creaked noisily open, and Lash started backward, making the snuffling noise he often did when he was surprised by something.

A boy’s face appeared, with short untidy hair a bit like a bird’s nest on his head.

“Who you looking for?” he said.

“Oh — er — no one,” I replied, rather stupidly.

“Why get on your knees to look down the cellar then?” he asked suspiciously. “Lost something?”

I cast a wary glance into the yard behind me. “Do you know a bosun?” I asked.

“My Pa,” said the boy. “He ain’t here. Who wants him?”

“It’s not that I want him,” I said. How much ought I to tell this boy?

“You off the Sun of Calcutta?” he asked, evidently believing like everyone else that I was some sort of sailor boy. “What you come here for?” He was starting to be hostile. “What’s your name?”

“Mog,” I told him. “Where is your Pa?”

“Search me. Don’t know how long he’ll be, neither. All day and all night. Three months. Five minutes. Probably getting drunk at some tavern. And you’re lucky Ma Muggerage ain’t here neither, or she’d have your hide for a wash-leather by now, crawling round here.” It was only now that he noticed Lash, who came nosing forward to try and stick his nose in between the bars of the grating. The boy grinned, and I suddenly saw something in his big eyes I thought I recognized.

“Can you come out?” I asked him.

His eyes lit up. “No — but you can help me out. See that pink door there? There’s no lock on it. You’ll find a big heavy barrel in the scullery there. Shift that, and there’s a trapdoor I can get out of.”

I got up off my knees and led Lash over to the scullery door. It opened easily, shedding flakes of old pink paint as it swung open. A bare little room with a stone floor met my eye, cobwebs dangling like flags from the ceiling. There was no furniture except for a large empty washtub and a big keg standing against one wall.

With difficulty, I pushed the keg aside, an inch at a time, until a small square wooden trapdoor was completely uncovered. As I bent to knock on it, it opened upward towards me, making Lash sneeze again with gruff surprise.

“Someone keeping you prisoner in here?” I asked the boy, panting from the effort of moving the barrel.

“Not far off,” the boy grumbled, climbing out. He was dressed in clothes very much like mine. Indeed, as he stood up in the little scullery I suddenly saw that he was similar to me in several ways, and some of the events of the past couple of days started to make more sense. “Good thing you came by,” the bosun’s boy said, grinning with gratitude. “Sorry, what did you say your name was?”

“Mog,” I said, “and this is Lash.” The boy reached out a hand and Lash’s damp nose met it, pulling back in disappointment when he found there was nothing to eat in it. The boy laughed. For the first time he looked at me properly.

“Your clothes are all wet,” he said.

“Sorry,” I said, “I, er — was playing in a pump.”

“Sounds fun,” the boy said, “it’s so hot. It’s been awful down in that cellar these last few days. But my Pa, and Ma Muggerage, reckon I should be kept out of mischief. I reckon the pair of them ought to be locked up in there. They cause more mischief than anyone else in London.”

“They didn’t mean you to get out easily,” I said. And then: “What sort of mischief?”

“Not sure I know, exactly,” the boy said, “they don’t tell me nothing. But they’re both in it. People come to see ’em in the middle of the night. They go off at all hours, chasing people, carrying things, bringing money home. People leave notes. I see bits and pieces, but never the full story. Know what Pa brought home the other day? A camel.”

I stared at him.

“I think,” I said, “there’s a story I ought to tell you.”

His name was Nick (“Dominic, by rights, they say, but no one ever called me that before”), and he was the bosun’s son. His mother had died when he was very young, and he had been placed in the care of a formidable woman called Mrs. Muggerage, whom he hated, and who quite evidently hated him back. He’d seen his father rarely, since he was most often away at sea, coming home between voyages to pay Mrs. Muggerage for looking after his house. At one time Mrs. Muggerage used to pretend she treated Nick like a king; but when it became clear the bosun didn’t care how she treated him, she dropped the pretense.

“She’s always knocked me about,” he said, “treats me like a dog. Worse,” he added, scratching Lash under the chin. “It’s twice as bad just now, ’cos my Pa’s home, and they both hit me as hard as the other. At least when Pa’s away there’s only her to look out for.” He’d been forced, for most of his life, to live by his wits, and he freely admitted he’d become a habitual thief. His father had taken him to sea a few times, and in foreign cities he’d seen people with fabulous wealth, animals he’d never heard of before or since, and women more beautiful than he’d ever imagined. But the violence and harshness of the sailor’s life frightened him, and he hated the storms and the poor food; and his father’s embarrassment at his son’s lack of aptitude for life at sea had quickly turned to contempt. “He says I’m soft,” he grumbled, “he’s always saying I’m soft, whatever I do. He hates me for it, Mog, really hates me. But onboard ship, they do things — well, they do things you’d never believe if I was to tell you.” He was supposed to accompany his father on the voyage from which the Sun of Calcutta had just returned: but less than an hour before she set sail he’d sneaked ashore and hidden until he was quite sure she’d gone. Now that his father had returned he was paying the price. “Most sailors would get flogged and left for dead for that kind of thing,” he said, “so I s’pose I’m lucky to get away with being locked up in a cellar.”

“You’ve got a Pa, at least,” I said to him. “I’ve got no parents or family at all, that I know of.”

“Reckon I might be better off without, sometimes,” he said in a low voice.

In practice, it turned out he was able to slip away from the bosun and from Ma Muggerage regularly, and for long periods, without their worrying too much about where he was. He knew the streets of London as if they were part of his body; and it wasn’t just their layout he knew, but their different characters, which were dangerous and which were safe, who lived in them, whose favor to court and whom to avoid, how to get from one place to another in the quickest possible time, and how to disappear completely. His best friend was a dwarf in Aldgate who’d taught him to read. “I didn’t used to see much point in it,” he said, “I used to think, if you want to know something, why not just ask someone who knows? Whatever someone can write down, they might as well tell you out loud. But I changed my mind. Believe it, Mog, I learn more things off books and papers now than ever anybody tells me,” he said. “Folks think I can’t read, see? So they leave things lying about. It’s my best secret.”

“I can’t remember learning to read,” I said, “I just — always could, I suppose. I must have learned while I was in the orphanage. But I can’t say I know who taught me.”

“You too!” he enthused. “Well, you know what it’s like then. Easier to find things out, easier to fool people and lead ’em astray. Know what I do? Sometimes I write notes for my Pa to find, making out they come from someone else! I can find out gentlemen’s business just by picking their pockets. Oh, I know things I’d never know in a million years if I couldn’t read.” When I told him I worked in a printer’s shop, his eyes grew wide with envy. “Imagine!” he said, “posters and newspapers and announcements! You must know more of what’s going on than any kid in London!”

His eagerness to listen spurred me on. I told him about the men at Flethick’s, and about the man with the mustache, and about Coben and Jiggs and how I’d come by the wound on my head, and about the chest and the great knife and the Sun of Calcutta and the golden lantern and the man with the stammer … and all the time Nick’s eyes grew bigger and bigger until they’d almost pushed everything else off his face.

“What a detective you are!” he said admiringly. I laughed. “But listen,” he said, urgently, “the camel all those people are after is still here. In this house!”

“Where?” I asked, “in the stable?”

Nick pretended to laugh. “Very funny,” he said. Then he saw I hadn’t got the point. “It’s not a real camel,” he explained. “Look, come with me. I’ll show it to you.”

There was a door from the scullery, leading up a flight of stairs into the house. “Who’s that man in the stable?” it suddenly occurred to me to ask, as Nick led me through the untidy rooms.

“What man?”

“There’s an old creature asleep under a horse blanket in there.”

“Can’t say. ‘S not our stable, that. Might be a drunk,” Nick said. “Now then — this is the room he’s got it hidden in, I bet.” We were standing among a pile of odds and ends so extraordinary it made a rag and bone shop look tidy. Old clocks, bits of cloth, pieces of wood, ropes, brass trinkets, pewter mugs, odd shoes, rolled-up rugs, tins, candles, a wooden leg, hats, bird-cages, and meat forks were just some of the things I could see stuffed into tea chests and spilling out over the floor and the window seat. Lash went nosing and clattering among it all, his tail flapping with absorption.

“All looks pretty useless to me,” I said, surveying the piled-up junk.

“Probably,” Nick said, “but that’s what folks are meant to think — know what I mean? It’s a good place to hide real valuable stuff, under all this junk.” He began pulling blankets out of a nearby chest. “For instance,” he said, “look what’s here.”

He’d found it. An ornament in the shape of a camel — a foot high, no more — with a single hump and a long neck arching outwards at the front, and a rather dazed expression on its face, as though it had just been clouted over the head with a frying pan. It was made of brass, and was designed so that it could stand on its four legs. Bits of it had turned a crusty green.

“That’s the camel?” I said, disappointed.

“Yes, but there must be something valuable about it ’cos he was pleased as punch when he brought it home,” Nick replied. “I heard him talking to Ma Muggerage and he was laughing fit to burst, as though he’d got the Crown Jewels.”

“I think,” I said, “Coben and Jiggs expected this to be in the chest they stole. They kept saying the bosun had it, and asking me where it was.” I turned it over in my hands. “Are you sure this is the right one? This couldn’t be a false one, to throw people off the scent?”

“That’s the one he was gloating over,” Nick said, “I saw it with my own eyes. And shall I tell you something else? He’s got customers who are interested in this. He told Ma Muggerage he was meeting some men at the Three Friends to arrange a little deal.”

“When?” I asked eagerly.

“Dunno. Maybe now. But more likely at night. That’s when all their shady stuff goes on, far as I can —” He stopped, and his brow furrowed. “I’m not so sure I should be telling you all this,” he said. “How come you’re so interested anyway?”

I shrugged. “I don’t know,” I said, truthfully.

“You seem to know plenty about thieves, for an honest lad. You’re quite excited about it all, aren’t you?”

I had to confess I was.

“Well, you shouldn’t be,” he said. “If you take my advice you’ll stay out of it, and then you’ll still be an honest lad when all these characters are locked up or dead. Look at this.” He reached into his pocket for something — a crumpled piece of paper. He handed it to me, and I unfolded it curiously.

Dont Think You Can tred

on ur patch.

You might hav less frends

Than you think. Eys ar

watchin you evry niht.

Eys ar watchin you now.

“This came last night,” Nick said, “pinned to the window frame, it was. There’s men after his blood for taking this.” He lifted the camel, and it stared stupidly at me.

“He wrote a note to Coben and Jiggs,” I remembered, “and drew a big eye on it to warn them. Seems everybody’s watching everybody else.”

Suddenly there was a clatter from downstairs.

“Oh no! Someone’s come back!” Nick flung the camel into the chest and grabbed my arm. “Run,” he said, “get lost, or we’ll both be killed.”

“Lash!” I hissed, and his startled head popped up from behind a chair. “Come here boy!”

But feet were already stomping up the stairs. “NICK!” came a bellowing woman’s voice.

“It’s too late,” I said, looking around in a panic, “We’ll have to hide.”

“NICK!” As the door burst open I dived behind it out of sight, and Lash skidded to a halt by my side, leaving poor Nick standing in the middle of the room with his hands in his pockets.

“Who let you out?” the woman screamed, and as she advanced into the room I saw that she was huge, her bulk wobbling like a badly stacked haycart. Her arms were bare, and as she moved them angrily they reminded me of hams swinging in a butcher’s window. In one of her fists, I suddenly saw, she was holding a big square meat cleaver. Anyone who got in the way of that wouldn’t stand a polecat’s chance. I saw Nick glance towards me, and he moved his head slightly to tell me to be gone.

“What are you twitching at?” the woman bawled at him. She moved forward with her arm flexed as though to clout him, and Lash responded with a sudden growl which made her stop in her tracks.

“What was that?” she screeched. “Is there a dog in ’ere?”

I wasn’t going to let Lash anywhere near the meat cleaver, with which the fearsome woman could have split his head in two with a single stroke. The only thing for it was to run; and, dragging Lash by the lead, I slipped between the door and Mrs. Muggerage’s back and launched us both headlong down the stairs. Too late, she wheeled around and saw us half-running, half-falling towards the scullery.

“OY!” she roared, so loudly that the whole house seemed to vibrate. Tripping over one another in a tangle of arms and legs at the bottom of the stairs, Lash and I struggled to run as Mrs. Muggerage’s footsteps began clomping down the steps after us. Lash’s lead was caught around my ankle and I yanked it in a panic, making Lash yelp as the rope snagged and bit into his neck as he tried to right himself. After what seemed like a lifetime, we finally scrambled onto our six feet and ran; and as we did so, the meat cleaver whizzed past my ear, missing me by no more than an inch.

Cramplock was busy in the printing shop when we came in, but that didn’t stop him eyeing me severely over his half-moon glasses. Guiltily, as though it were all his fault, Lash slunk up the stairs to his basket — leaving me to face the music.

“Now you crawl in, Mog Winter,” Cramplock said reproachfully, “where do you suppose you’ve been for the best part of the day?”

“Sorry, Mr. Cramplock,” I said, “I had meant to come back sooner, only—“ What was the use of explaining where I’d been? “I was feeling a bit ill,” I mumbled, making a show of holding my bandaged head, but knowing it was a poor and transparent excuse.

“Not too ill to gallivant round the city with your dog,” he responded sharply. “If you weren’t feeling well you could have stayed upstairs and got some rest. I might have been able to spare you, if you’d asked.” He was speaking quietly, but it was obvious he was furious. “I just expect to be told if you can’t work, Mog,” he pointed out. “It’s not unreasonable.” I didn’t say anything. He was quite right, and my cheeks burned with embarrassment at his scolding. I went over to the bench where some blocks of type were waiting to be dismantled. I’d become good at reading the type before it was printed, even though it was back to front and all the letters were the wrong way round. I could see the blocks had been used for an advertisement.

“Been doing advertisements?” I asked. I was trying to sound bright, but there was a lump of shame in my throat as big as a plum.

“Yes, Mog, seeing as you weren’t here to do them,” Cramplock replied sourly. “Fifty for the chemist.”

I picked up a sheet of paper to lay over the inky type, and lifted it off. It had printed a little square advertisement with a picture of a medicine bottle, and the proud announcement:

MRS. FISHTHROAT’S

SPLENDID SYRUP

SOOTHES CHILDREN TO SLEEP

CURES RECALCITRANCE

PEACE & CONTENTMENT

IN THE HOUSEHOLD!

Money-back guaranteed

We’d printed this advertisement many times before. I’d always wondered what “recalcitrance” meant: I had a suspicion it was just a long word for wind.

“Stop wasting time, now that you’re here, and take those forms apart,” Cramplock was telling me, “I’ve an important job coming in this afternoon and I’ll need the type.” I set to work quietly, knowing I’d be in real trouble today if I stretched his patience any further. I began the slow, messy job of taking each tiny little metal letter and throwing it back into the right compartment of the type case. It was sometimes difficult to tell the letters apart, and if I got them mixed up I used to get shouted at, or worse. Capitals weren’t so bad — but with the lowercase letters, because you had to remember that they were back to front, it was often hard to get “d” and “b” and “p” and “q” in the right boxes if you weren’t concentrating. I once printed a whole five hundred playbills in which the name of a celebrated actor called Mr. Thomas Tibble came out as “Mr. Thomas Tiddle,” and I hadn’t noticed until they were all done. Cramplock wasn’t normally a violent man, but I thought he was going to knock my brains out of my ears that day.

“When you’ve done that,” Cramplock said, “you can pull a hundred of these.”

He’d set up the type for another elaborate poster; and after he’d disappeared into the back room to do some accounts I went over to have a look. Even without taking a copy I could make out what it said. It had type of several different sizes, and an engraving which seemed to be of some sort of animal.

EXHIBITING FOR ONE MONTH ONLY AT

MR. HARDWICKE’S

at BAGNIGGE WELLS

the Most REMARKABLE CURIOSITY

that Ever was Seen!

CAMILLA

the PRESCIENT ASS

The only BEAST in the WORLD guaranteed to tell FORTUNES and Prophesize EVENTS with Perfect Accuracy also to Read Cards, Interpret Horoscopes and FORETELL INHERITANCES OF WEALTH This EXTRAORDINARY CREATURE is to he Displa’d DAILY and will perform Demonstrations at the Hours of 11, 12, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 o’Clock Admission on payment of One Shilling

The engraving was of an absurd-looking creature with two large ears, and a person standing next to it holding up his hands in what was meant to be astonishment.

Laughing, I reached for some scrap sheets of paper to make a couple of test copies, to make sure the poster was properly laid out.

“Do you suppose this ass really can tell fortunes, Mr. Cramplock?” I ventured to ask, pulling out one of the tests and examining it.

Cramplock grunted. “Not if Hardwicke’s got anything to do with it,” he said. “Biggest swindler in London. The poor fools who flock to see it will probably find it’s an ass standing in front of a curtain, with his wife hiding behind the curtain shouting out.”

I printed off five or six more and looked them up and down with admiration.

“Did you give my bill to Flethick?” Cramplock suddenly asked.

I froze.

“Ah, Yes,” I said.

“Good. That’s all right then. He owes me plenty, and it’s high time he settled his account. The number of things —“

“But,” I butted in, “he didn’t give much impression that he’d pay.”

Cramplock looked at me intently and rubbed his cheekbone. “Why? What did he say?”

“He, er — he told me to tell you he wanted no bill, Mr. Cramplock,” I said, my face going bright red with embarrassment again, “and he, ah — burnt it up.”

The little man’s eyes nearly fell out of his head, and would have done if his glasses hadn’t stopped them. “He what?”

“Erm — burnt it up,” I said, starting to wish I’d never told him. He still showed no sign of understanding. “Burnt it,” I repeated helpfully, trying to smile. “Up.”

Cramplock made a noise like a chicken. “But — but — but — why did you let him?”

“I didn’t have much choice,” I said. “He’s not a nice man, Mr. Cramplock. There were lots of his friends there. He was behaving very strangely.”

“He’ll behave more strangely when I get my hands on him,” squawked Cramplock. “Burning my bills! Who does he think he is?” He wasn’t just cross now, he was enraged. He pushed me out of the way of the press and started printing the rest of the posters himself, working the machinery furiously and almost throwing the ink at the roller. For the next ten minutes he carried on muttering to himself, occasionally slamming things down on the table. I sat picking at the type in the cases, not daring to say any more.

After a while he addressed me again. “By the way,” he said, “that poster you did.” He still sounded annoyed.

“The convict?” I said, wondering what was wrong.

“Yes, the convict. A man from the jail came to see me yesterday. It seems you made a bit of a mistake with the picture.”

A horrible dread crept over me. “What mistake?” I asked, quietly.

“You printed the wrong face,” Cramplock said, irritably. “The wrong engraving. That wasn’t the fellow at all. That was some other convict from months back.”

So Bob Smitchin had been right. But I felt sure that was the engraving Cramplock himself had given me to print — so it was his mistake, not mine, though I couldn’t possibly say that to him in his present mood.

“Made me feel quite a fool, the fellow did,” Cramplock was continuing. “How can you expect to catch a criminal when you put out a poster with somebody else’s face on? He must be laughing like a jackass, wherever he is.” He flung an inky old rag at me. “And more to the point, the jail won’t pay!” he shouted, getting more and more angry. “Because we got it wrong! Call yourself a prentice? Well, if I get no money for the posters you get no wages this week, and that’s that.”

“But—” I said.

“Don’t give me any sob stories, Mog Winter. First you disappear for nearly a whole working day without any explanation. Then I trust you to run a simple errand and you come back from Flethick’s with nothing but a pathetic tale about how he burnt his bill — fact is you probably lost the bill before you even got there. Don’t argue, Mog! And then to cap it all you print a hundred pictures which are meant to be a man called Coben only the face ain’t a man called Coben, it’s some other fellow who was hanged months ago. It’s no good you looking like that, Mog; whether you’ve been sick or not you won’t get any sympathy today.”

I must have gone as white as a sheet. I felt as though a knife had hit me in the back.

“Did you say C-Coben?” I stuttered. “What on earth makes you say Coben?”

“Because that was the name of the escaped convict, as you well know,” Cramplock said.

“His name was Cockburn,” I protested.

Cramplock wheeled. “Don’t you know anything, Mog Winter? It’s pronounced Coben. It might look like Cockburn, but you pronounce it Coben, as a rule. So now you know. And you can get that sick look off your face, because I’m not changing my mind about your wages!”