The night was full of strange dreams.

The faces in the fog had returned. Cramplock was one of them, roaring at me in rage, hurtling away from me as he shouted, but coming back several times to remind me of my negligence. Some of the figures who ballooned up out of the mist held up lanterns, as though to peer into my face, and I had to squint and screw up my eyes to stop the light from dazzling me as they drifted off. Mrs. Muggerage had appeared, cleaver in hand, roaring silently into the murk, and the image of Nick’s anxious little face with his shock of black hair swam around her, dodging the cleaver as she swung it mercilessly from side to side.

And I’d dreamed of the man from Calcutta, too, though he hadn’t been one of the faces in the mist. This time not just his head but his whole body had become that of a crow, sleek and shining, his eyes glinting jewels which darted and pierced; and he was sitting on the edge of my bed, in the dream, watching me. But instead of feeling frightened of him, I felt as though he were guarding me. Perched on my bedpost, alert but protective, his presence seemed somehow important and comforting, like the ravens at the Tower.

I woke in a sweat, with Lash licking the salt from my temples. Light was flooding in through the window and I could hear the sounds of morning activity outside. The first thing I did was sit up and check that the camel was still there — and, sure enough, it was still in its raggy bundle in the bottom of the cupboard.

Cramplock was already at work. His hands and face were black and smeared with ink.

“Strange letter arrived this morning,” was the first thing he said to me.

“Who from?”

“Can’t say.” He reached for a stiff piece of paper. “Make any sense to you, Mog?”

I scanned it quickly. “Where was it?” I asked him, uncomfortably.

“Nailed,” he said, dramatically, “to the door.”

I swallowed.

CLEAVER BOY,

SO CLEAVER FIND HIS CAMEL.

I SHOW HIM DEATH SOON.

And beneath this extraordinary message, the strange letters again:

It had obviously been left last night by the man from Calcutta, and there wasn’t much doubt about what it was getting at. The way he’d misspelled “clever” was rather unsettling, I thought, under the circumstances.

“I can’t make head or tail of it,” Cramplock said, “some sort of joke I suppose — from a friend of yours, is it?”

“Mm,” I said.

I SHOW HIM DEATH SOON.

Not an especially funny joke, I was thinking — and my face must have made it clear I wasn’t amused. The man from Calcutta had had a good try at “showing me death” the night before. It was clearer than ever that, after he’d failed to find the camel that evening at Coben’s hideout, when I threatened him with the sword, he had become convinced I was working for Coben and Jiggs, and was hiding the camel for them. He must have seen me bringing home a bundle last night, and guessed straightaway what it was.

It was absolutely vital to find another hiding place for the camel — and I had to do it today. I was beginning to wish I’d taken Nick’s advice and left it where it was in the first place.

“Mr. Cramplock,” I said, “has, er — has somebody come to live next door?”

He stared at me. “Not as far as I know,” he said. “Nobody’s lived there for ages. It caught fire years ago — and it’s been empty ever since, I think.”

“Only — I thought I could hear someone moving about in there,” I said cautiously.

Cramplock shrugged. “Probably some poor old soul who’s broken in, using it as a place to sleep. But it’s not safe. As far as I know there are no floors in there.”

I said nothing.

“Is something wrong, Mog?” Cramplock asked. “You’ve been acting a bit strange lately, as if there’s something on your mind.”

“Nothing much,” I said vaguely, not wanting him involved.

But for the whole of the day I was miles away, pondering over the man from Calcutta and the house next door and the whole camel affair. The more I thought about it, the surer I was that someone had been moving about next door the other night, and that it had probably been the man from Calcutta. He was hiding in the house next door, to spy on me. I was so preoccupied I couldn’t concentrate on my work, and Cramplock had to tell me several times to stop daydreaming. At one point when I’d been told to pull out a long length from a roll of paper, I was particularly careless and managed to tear a huge gash right up it; and this time he shouted at me.

“Wake up, can’t you?” he barked. “Did you knock your brain out when you hit your head the other day? Just pay attention to what you’re doing or you’ll get another knock you won’t forget.”

He took me by the arm and dragged me through into the filthy little storeroom where he kept most of his paper and old woodblocks. “You can scrub the floor and the cupboards in here,” he said, “seeing as you don’t seem to be able to do anything more complicated. This has needed doing for months.”

More like years, I thought grumpily, as I began the job. I had to move all the heavy boxes out of the way first; and, crouching on my knees, I discovered astonishing amounts of dust and rubbish, rags and inky old fluff, which had accumulated behind the boxes and cupboards over a long period of time. It made me cough so hard I thought my lungs were going to turn inside out. After half an hour I looked as though I’d been scraped out of a forgotten corner myself. As I was picking up the final few scraps of discarded paper before moving the boxes back against the wall, I noticed one with some rather surprising words on it.

It was a short handwritten letter in a rust-colored ink. It wasn’t addressed to anyone by name, and it wasn’t signed. It just said:

I dont’t appreciate the deceit, and neither do some of my friends. You can hide nothing, and you could save yourself a great deal of trouble by remembering it.

I thought I had made myself quite clear: but it seems you require a further reminder.

This is most certainly your final warning.

I read it through several times. The handwriting and spelling suggested someone well-educated: it was certainly a far cry from the garbled notes of the man from Calcutta, or those with little drawings of eyes which the villains had been exchanging. How had it got here, among the scraps of Cramplock’s storeroom? I don’t think I was supposed to see this: but I felt sure it must have been sent to Mr. Cramplock, and it suddenly seemed as though he must know something he was keeping quiet about.

A sudden thought occurred to me, and I lifted the paper up to the light from the little storeroom window. I wasn’t entirely surprised when I found the strange watermark of the dog yet again, curled around so its nose was touching its tail.

I jumped as the storeroom door swung open suddenly, and made a poor fist of hiding the note as Cramplock popped his head in. I was convinced he must have noticed it in my hand; but he didn’t ask me about it. Instead he said:

“Are you nearly finished, Mog? Only I want you to go out with some bills for me.”

I beamed at him. “I’ve, er—just got a couple of boxes to put back,” I said, going red.

“It looks much better,” said Cramplock, surveying the flags of the floor and probably remembering for the first time in years what color they were supposed to be. “But these must be delivered — now.” He waved a fat handful of envelopes. I clambered to my feet, and lumps of clinging dust floated into the air like thistle seeds.

Lash was excited at the chance to get out of the dusty shop and was sitting patiently by the door even before I emerged from the storeroom. As I picked up the envelopes, Cramplock grunted. “Just make sure you don’t lose them, and bring me back some cock-and-bull story about people burning them up. Or about … about them being eaten by goats, or trampled by giants.” He seemed very pleased with his own sarcasm.

“I won’t lose them, Mr. Cramplock,” I said, “I promise.”

“You’d better not,” he said, “or the last printing job you ever do will be an advertisement saying W. H. Cramplock seeks a diligent boy to be a printer’s devil.”

I looked at him to try and decide if he was joking or not, but as he turned his back I decided he wasn’t. Scanning the various addresses on the bills, I had a sudden idea. I’d have to be out of the shop for a good hour, delivering all these. And at least one of the bills had to be delivered fairly close to where the bosun lived. I might as well try and get a message to Nick while I was at it.

Jamming the bills into my pocket and knotting Lash’s lead hastily around his collar, I dove out into the sunshine. I couldn’t resist a glance up at the blackened face of the house next door. Nothing appeared to stir; but my imagination conjured up eyes watching me from every one of the dark windows, and I ran past with a shudder of fear.

But when I got to Lion’s Mane Court I found Mrs. Muggerage was very much in evidence. From the narrow passageway I could see her hanging up her laundry in the yard, moving between the dangling, dripping garments like a big ape in a forest of linen. I couldn’t possibly sneak in unnoticed. I ducked back out of the passageway and tied Lash to the nearest post.

As I was doing so I became aware of a familiar chant from down the street. An old cart was clattering along, driven by a toothless old gypsy in a brown cap. He was a rag and bone man. Suddenly getting an idea, I rushed up to him and flagged him down.

Mrs. Muggerage was no doubt surprised to see a rag and bone cart jolting its way into the yard, its wheels bumping over the pitted ground.

“Any rags or bones,” the old man moaned, looking at her. Setting her face in a grimace, she marched over to him.

“What do you mean by draggin’ yer flea-ridden old cart in ’ere?” she screamed. “There’s no rags and no bones, now get lost!”

“Rags or bones,” the man wailed again. I wasn’t sure whether he was an idiot, or just pretending to be; but I was very grateful for it. While Mrs. Muggerage blared at him, I crept down from the back of the cart, where I’d been hiding among the smelly rags. Ducking between the big sheets which hung around the yard, I scuttled for the cellar grating.

I didn’t dare call, or make a sound of any sort. There was a light wind, and every now and again a dangling sheet blew aside to afford me a view of Mrs. Muggerage, just a few feet away, arguing with the blank-faced old carter. In the back of the cart I’d scribbled a tatty note with a stub of a pencil I had in my pocket.

Nick

TROUBLE!

DOLLS HEAD 6

M

A scream went up as the ragman’s horse began eating Mrs. Muggerage’s washing. Fishing down through the grating, I slipped the note in through a crack in the dirty little window, and started to tiptoe back to the cart.

But Mrs. Muggerage had begun clouting the feeble old carter over his flat-capped head and, finding the onslaught too terrible to bear, he’d geed up his horse and rattled off out of Lion’s Mane Court before I had a chance to leap back among the rags. The big woman was just turning away, wiping her hands on her bulging sides, when she spotted me lurking behind a sheet.

A big smile of satisfaction spread across her beefy face and, without warning, she advanced. It was like trying to dodge a collapsing house. She barged through the yard, saying nothing, merely grinning as I tried to avoid her swiping arms. If one of them had hit me I’d have been out cold.

Mrs. Muggerage may have been big and strong but fortunately she wasn’t especially agile; and her grin began to look rather strained as I led her like a matador through the maze of wet linen. Waiting behind an enormous pair of bloomers, hanging from the line like a ship’s mainsail, I watched her calculating her next move. When she was almost close enough to reach out and grab me by the throat, she lurched; and I ducked, and was gone. Looking back as I sped out of the yard I saw her bulky frame tangled up in her own bloomers, fighting for air amongst the billowing material, wrapping it around herself in her thrashing confusion until she’d twisted the entire washing-line up and pulled it onto the filthy flagstones.

“What you been doin’ to your head then, Maaster Mog?” asked Tassie as I walked into the Doll’s Head that evening.

“A kid threw a brick at it,” I told her, truthfully.

“In a fight, was you?”

“Not as such,” I said meekly.

“Well if you don’t mind me saying,” Tassie said, polishing her taps, “you don’t smell so fresh this evenin’, Maaster Mog, neither.”

There were four other people in the taproom, all of whom I knew. No spies in here, then, it seemed — but no Nick either.

“Is it six yet, Tassie?” I asked her.

“You take a look over there, Maaster Mog,” Tassie replied, “at that sizable clock what’s been here since the first day you set foot in here, and what’s more since long before you was ever born. And you tell me if it’s six yet.”

Sheepishly, I glanced over at the longcase clock against the wall, with its slightly tarnished brass face which was at least twice the size of my own head. Five minutes past six. Tassie was obviously in no mood to be trifled with this evening.

Lash’s nose appeared beside me at the bar, sniffing and dribbling slightly at the scent wafting from the little back room. “Do we smell stock, Tassie?” I laughed.

“Maybe it’s more than stock you smells, Maaster Mog,” she said, “maybe it’s a big pot o’ my best knuckle soup!”

My eyes lit up, and Lash whimpered in anticipation as Tassie disappeared, still laughing, into the back.

Trying to appear casual, I tightened my grip on the handles of the big canvas bag I’d brought with me, and heaved it under the table. To any observer, I hoped, it looked like a bag full of rolls of poster paper. What nobody else knew was that hidden among them was a brass camel which was apparently the most coveted object in the city’s criminal underworld. Although I was trying not to draw attention to myself, I was terribly nervous and I didn’t dare let go of the bag for a single second. I yanked at Lash’s collar to make him sit down quietly next to it.

Looking up, I noticed one of the drinkers looking at me, a disheveled old soul called Harry Fuller who drove a stagecoach between here and Cambridge.

“Hello, Mr. Fuller,” I said, “it’s been a nice day again.”

“Noith for thumb, maybe,” he replied. He spoke rather strangely as a result of his having no front teeth — they’d been missing for as long as I’d known him. When he drove his coach he used to hold the reins with both hands and keep his horsewhip clamped in the gap between his remaining teeth, poking out of his mouth like a kind of long floppy pipe as the coach lurched by. “Noith for mouth folk, I don’t wonder.” I could tell he was in a bad mood, and there was still no sign of Nick, so I asked him what was the matter.

I immediately wished I hadn’t. In his gruff lisp, he began to rant, about how much trouble he went to to ensure that his passengers were comfortable, and how much of a sacrifice it was, driving a coach back and forth in all weathers and never being at home with Mrs. Fuller and the five or six little Fullers — he didn’t seem to be able to remember quite how many children he had. But just as I was looking around the room to try to think of an excuse to talk to someone else, he said something which made my ears prick up, about his coach being stopped and searched by soldiers on his way out of London.

“Soldiers?” I asked.

“Thowdjerth,” he affirmed, flinging a fine spray from his mouth with every syllable in the evening sunlight. “Convict looth, they thed.”

So there was a search on for Coben. Oh, where was Nick? My mind raced again through the things I had to tell him, as Mr. Fuller grumbled on about how he was convinced the soldiers were just using the search for the convict as an excuse to rifle through passengers’ luggage, and how they were no better than uniformed robbers and highwaymen. “Crawled out o’ pigth-tithe and gutterth, mouth of em, Mathter Mog,” he was saying.

It was Tassie who finally cut short his grumbling, by returning with two deep bowls of soup. One she placed on the table in front of me, the other on the floor in front of Lash’s glistening whiskers. The sound of slobbering filled the room as he dug his nose delightedly into the soup.

“Might there be more?” I asked her.

She looked at me with mock disapproval. “You spoils that dog rotten,” she said.

“I didn’t really mean for him,” I said, reaching down to ruffle his ears. “I meant, for a friend of mine.”

“I dare say there might,” she said, amused. “What friend are you expecting?”

“Oh, just a lad I know,” I said airily. “If he comes. I asked him to.”

But the longer I waited, the more certain I became that something had gone wrong. Maybe my note had got stuck in the grille and he hadn’t found it. Or worse — what if the bosun or Mrs. Muggerage had found it first? Even now they might be marching over here. Every time the door opened I almost jumped out of my skin, half expecting one of the enormous couple to come stamping in.

To my relief, at just after twenty past, a small face peered round the taproom door, saw me, and hurried in.

“I’ve got a bone to pick with you,” he said in a low voice, as he sat down.

“What sort of bone?” I asked, putting the last spoonful of knuckle soup into my mouth.

“I’ve just had a good clouting off my Pa for something I never did. Nothing new that, I suppose. But —“ Suddenly he stopped, looked down at me, and wrinkled his nose. “Where’ve you been?” he asked; “you smell like a drain.”

“Thanks very much,” I said, “I had to hide in a rag and bone cart to get that note to you. But never mind that — what happened to you?”

“Pa came home this afternoon,” continued Nick, “saying he’d been to the ship. To the Sun of Calcutta, you know. And someone there told him I’d been snooping round asking for the captain. I never, I said. Don’t you lie to me, he says.” He did a passable imitation of his father’s throaty voice. “Wasn’t you described to me in perfect detail? Some sailor apparently told him there was a kid aboard wearing tarry breeches and a white shirt, skinny with a sprout of dark hair and a big cut on his forehead. That’s you, innit, says my Pa. Yes it is, I thought, and I know who else it is.”

“You didn’t—” I began.

“No, course I didn’t tell him,” Nick said. “But I got a bruise or two more to boast of, out of that little conversation.”

“I’m sorry, Nick,” I said.

“Course, he was in a foul mood,” Nick said, looking around nervously, “you-know-what being gone.”

“When did he find out?”

“Just this afternoon when he came in. He’d been out all night. He found the note, came down to bawl at me, threw me at the wall, and left again straight away. I don’t fancy being Coben or Jiggs when he gets his hands on them.”

Tassie came over with some soup for Nick. Lash jumped up when he saw it, but seemed quite crestfallen as he realized it wasn’t for him, and lay down again with what sounded very much like a sigh. As Tassie walked back to the kitchen I heard her telling someone, “Look at them two. Spitting image of each other, like a pair o’ magpies, they are, and twice as mischievous I’ll wager.” And she couldn’t resist a quick vigorous wipe at her taps as she went past them.

“Listen,” I said in a low voice, “I’ve got a story and a half to tell you.”

“Trouble,” quoted Nick.

“Yes,” I said. I looked around, just to make sure no one new had entered the room, and I told him all about the snake in the cupboard and the man from Calcutta lurking outside.

“Are you sure you didn’t dream it?” Nick asked.

“It did cross my mind,” I said. “But look at this.” Under the table I unfolded the note I’d received that morning, and leaned back to let Nick read it. He gave a grim smile.

“What does SO CLEAVER FIND HIS CAMEL mean?” he asked. “Does he mean Ma Muggerage’s cleaver?”

“I think he means ‘clever,’ doesn’t he,” I said. “He probably doesn’t speak English very well. I suppose he’s trying to say, ‘You think you’re so clever to find the camel,’ or something like that. But the point is, he knew I’d got it, didn’t he? I think it was the camel he came looking for at Coben and Jiggs’s as well, when he found me in the chest. And I reckon he’s watching us from the house next door to Cramplock’s. I bet he’s seen me coming and going all the time.”

“I told you it was stupid,” Nick said. “You’ve only had the camel a few hours and already you’ve had people coming after you with real live snakes and death threats.”

I was beginning to think he was right, but I said nothing. Nick continued to stare at the note in my lap. “What’s this?” He was pointing at the strange lettering.

“It’s writing of some sort,” I said. “I’ve seen it before. In the captain’s cabin, on a snuffbox lid. And it was on another piece of paper I got from Coben and Jiggs.”

“Keep your voice down,” Nick muttered. I stopped talking. I’d been getting too excited, and had forgotten. There was silence for a while as Nick began attacking his soup.

“What did you tell the sailor on the Sun of Calcutta?” he asked, after a while.

“Mmm? I told him, er — that — that I was the bosun’s boy,” I said, going red, “and that I was on an errand for my Pa — your Pa, that is. And that it had something to do with the East India Company. It sounded grand, I read it on a document.”

“So you told him you were me,” said Nick, drily.

“Sort of. Except I didn’t know you then. I didn’t even know the bosun had a boy. I — I guessed, because that’s who everyone seemed to think I was.”

Nick took another mouthful of soup, saying nothing.

“Anyway,” I said, anxious to change the subject again, “we’ve got to move the camel again. The man from Calcutta won’t leave the place alone till he’s got it.”

“Well, maybe it belongs to him,” Nick said. “Have you thought about that? Maybe he’d only trying to get it back because it’s his. Where is it now?”

“Here,” I said, “under the table. Don’t look! Someone might be watching.” Now it was Nick’s turn to look around nervously. I reached over and ate a spoonful of his soup. “I’ve got another note to show you,” I said, licking my lips. “I found it in the storeroom at the printing shop.” I fumbled in my pocket but couldn’t find the note, and I didn’t want to draw attention to it. “I’ll show you it later,” I said, “but I think it must have been sent to Mr. Cramplock. It’s like a — threat.” I tried to remember how the note had begun. “Something like, I don’t appreciate the deceit, and neither do my friends,” I quoted.

Nick grimaced to himself. “So let me get this straight,” he muttered. “You’re being watched by the man from Calcutta, who’s got a deadly snake as a pet, and who lives next door. Someone’s been sending you notes threatening to show you death. And Cramplock’s mixed up in it too, for good measure. This is too close for comfort, Mog. Seems to me you’d be better off staying away from there altogether.”

I shifted uncomfortably. “Oh, and something else,” I said. “Soldiers are searching for Coben. They’re turning out carriages leaving the town. A coachman’s just been grumbling at me about it.”

Nick scraped the last of his soup from his bowl, and sucked his spoon clean.

“I don’t know,” he said, “who Coben needs to hide from most. Those soldiers, or my Pa.” He looked at me significantly. There was silence. I could hear Tassie laughing. I couldn’t resist a quick glance down at the bundle at my feet.

“What are we going to do with this, then?” I asked at length.

Our shadows were long, stretching in front of us like stick puppets wherever the clustering of the houses gave way to the reddening sunlight. Every time someone rounded a corner unexpectedly, I jumped halfway out of my skin.

“Calm down, can’t you?” Nick murmured. “You’ll give us away.”

“How much further?” I asked. I was convinced it must be obvious to passersby what we were doing. That boy with the dog looks nervous, they’d be saying — ah, yes, of course, he’s taking a stolen camel to a hiding place in Aldgate.

“Not far,” said Nick. He’d already told me he was deliberately going to take me by a very indirect route, so as to lead any possible spies off the scent, and consequently it was taking us twice as long to get to our destination.

“Excuse me, now,” said a high-pitched voice from a dark corner. I was about to take to my heels and run for it, when Nick grabbed me by the shoulder. There was a dusty old man sitting up against a broken wall. Lash went over to sniff him and I called him back nervously.

“Did ye hear it, now?” the man was rambling, tunefully. “A most remarkable thing, it was, to be sure.” He spoke in a lilting voice like a pennywhistle. “A mooo — ost remarkable thing.” His face suddenly disappeared into itself like a sponge, and flopped back out again. It took a while for us to realize that this was meant to be a smile. “Music!” he added, portentously. “The most remarkable music that ever was.”

“Er — yes,” I said, pulling Nick away.

“Music,” the tramp was continuing, “like I never heard before. Like a bagpipe … like a flute … like a violin … like nothing I ever heard before in me life. What music is it,” he lilted, “that sounds like all the snakes of the world rippling over one another? Why should music like that be heard, now? Music from far away.”

Nick nudged me, to urge me on, and we left the tramp sitting there, laughing and softly singing to himself.

“Isn’t that strange,” Nick said, “what he was saying about music like snakes?”

“I suppose people like him imagine all kinds of music,” I said, “just like they imagine all kinds of sights. A drunk once told me he’d seen a woman with a horse’s mane and hooves going into a house. He swore all kinds of oaths he’d seen it.”

“It must be quite fun in a way,” Nick said, “to imagine you see and hear things. No difference between things that are real and things that are a dream.”

“Sounds like my life just now,” I muttered.

We turned a corner into a wide street, still busy with coaches and barrows; and Nick stopped by a little shop-front, so shabby it almost looked uninhabited. Just above our heads, over a low front window, I could dimly make out the words

SPINTWICE

JEWELER & SILVERSMITH

painted in smut-caked letters. I called Lash and took hold of his lead, and Nick knocked on the little door, which barely seemed high enough for us to get through, let alone a grown-up customer. After a few moments it opened and a child’s face peeped around it. When it saw Nick, the child pulled the door further open and disappeared inside. We followed him in.

“This is Mog,” Nick said when the door was closed. “Mog, this is Mr. Spintwice, my good friend.”

The person I had taken for a child was Mr. Spintwice himself. He was shorter than either of us, and his face, now that I could take in his appearance properly, was a strange mixture of infant and adult. He had rosy cheeks and a permanent broad grin, like a mischievous child of about five or six; but his eyes were quick and dark and, I suddenly thought, sadder than the rest of his face. He really looked most peculiar, and I took my cues nervously from Nick, watching his responses to the little man before deciding what I thought of him or how to behave.

“Mog,” he said, in a piping voice. “How do you do, Mog?” He reached up for my hand, all the time smiling in his unchanging way, and I shook hands with him slightly stiffly. “And this is?”

“Lash,” I said, hoping the tiny man wouldn’t be intimidated by a dog almost as tall as himself. But he had immediately recognized Lash’s trusting nature and was already reaching out the palms of his hands for exploratory licks. “Lash,” he said, “you are welcome.”

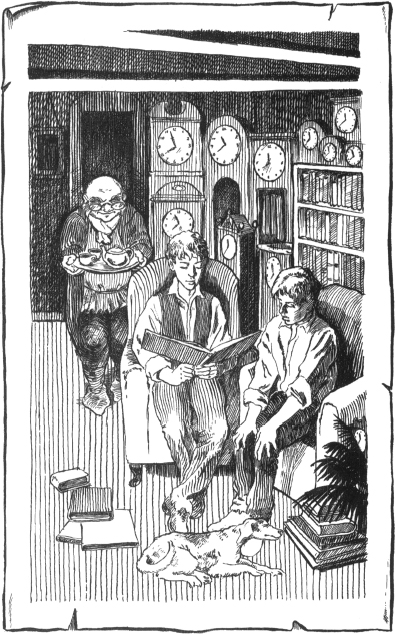

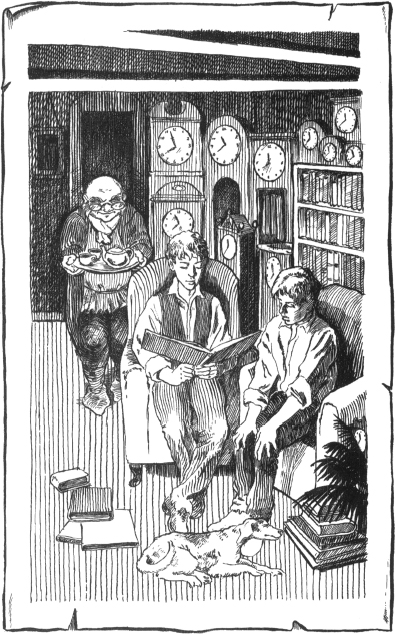

We followed him through the carpeted hallway into a tiny sitting room. “Nick and I have known one another many years,” he said in his precise little voice; and it was perfectly plain that Nick was entirely comfortable in his presence and didn’t think he was peculiar at all, so I said nothing. “Please sit in here. I can see you can’t quite believe your eyes. Well! Nick was just as surprised as you, the first time he came here years ago. If you make yourselves comfortable, I’ll fetch some tea.”

I looked around in wonder. There were armchairs, a mantelpiece, pictures hanging from a picture-rail, tables with plants in pots, a cabinet with glass doors revealing rows of books, and a warm welcoming fire blazing in the grate with neat fire tools and a coal scuttle beside it; but all of it was built to around half the normal size. This, and the presence of numerous clocks of various kinds ranged around the room, ticking and tinkling at several different pitches, made me feel as though we had stepped inside some extraordinary toy. Some of the clocks were so tiny, I marveled at how anyone could make a mechanism small enough to fit inside them. Others were quite big enough for Mr. Spintwice himself to climb in, next to the pendulum, and be hidden completely. When Nick and I sat down in the armchairs we filled them, finding them if anything a little tight. Even Lash looked around slightly bemused, as though afraid to wag his tail in case he knocked something off a shelf.

“I love this place, don’t you?” Nick said. “Listen to all those clocks.” He had barely sat down before he’d slipped out of his chair again and gone to kneel by the bookshelves. Soon he was opening one of the cabinets and taking out a big crimson book almost the size of a flagstone. “This is one of my favorites.” He dragged it back to his chair.

Something in my face must have betrayed my misgivings because, without my saying anything, he leaned close to whisper in my ear.

“Don’t worry,” he said. “Spintwice is all right. I think we should tell him the whole story, and see what he says. He’s a jeweler, so he might be able to tell us a bit more about the camel. And he’ll hide it for us, I’m sure.”

The longer I listened to the mechanical music of the clocks, the more it seemed to overwhelm us, lapping round us, spinning us into a web of sound.

“Why don’t you stay here?” Nick whispered suddenly. “Don’t go back to Cramplock’s. The man from Calcutta’s too close.”

I was unsure. I was genuinely afraid we might have been followed; and if I stayed here, there was every chance I’d just be putting the dwarf in unnecessary danger too. There was something about the familiarity of Cramplock’s that made me feel instinctively safer there; and, despite having Nick’s word for it, I still didn’t know Spintwice well enough to feel I could fully trust him.

“I’m still not —“ I began; but Nick was immersed in the book again, oblivious now to sights and sounds around him, completely and instantly relaxed. His eyes were wide as he took in the rich decoration which spread across both pages: figures in red and purple, woven patterns in gold leaf along the pages’ edge, and a Moorish landscape with two figures clinging to a brightly colored flying carpet. He seemed a different person altogether from the watchful, edgy, suspicious boy I’d met at Lion’s Mane Court. I suddenly realized how little I still knew about Nick. I wondered how he had ever encountered this strange little man, whose tiny house and wonderful bookshelves seemed such a world away from his violent home life. “He’s about the only grown-up who’s ever really been kind to me,” Nick had told me on the way here. My eyes wandered around the shelves of books, fascinated, enticed by the patterns and lettering on their spines. They looked impossibly rich and full of promise: no book ever printed at Cramplock’s had been as splendid as these, I felt sure. What on earth would Nick’s father say if he could see him sitting here, leafing through them?

“Does your Pa know you come here?” I asked him.

“There’s a lot my Pa don’t know,” he murmured, unconcerned.

Mr. Spintwice came back with a tray of teacups, again miniaturized to match his size; and he had also brought a dish of water and bread for Lash, which he put down in front of the fire. It was at this point that I decided I liked him.

“It’s a very nice surprise to have visitors, I must say,” he said, after taking a sip or two. “And at such an unexpected hour!”

“I’m sorry if we —“ I began, but he cut me off.

“Not at all! A pleasure, a sheer pleasure, Mog,” he said, “an unexpected hour is the very best hour for visitors! It would be boring always to have guests turn up when you expect them.”

Lash had made himself completely at home, curling up in front of the fire as though he’d lived there all his life. My suspicions were beginning to melt away, and I found myself thinking about what Nick had said and being very tempted to stay here, cocooned in this warm music-filled little sitting room, reading book after book. I was flooded with a strange sense of safety and wellbeing, a feeling so unfamiliar it gave me goose bumps.

“We really called to ask a favor,” said Nick, rather apprehensively, putting down the book.

“Of course! Anything I can do for two such handsome fellows.”

Nick looked at me. “It’s quite a long story,” he said. “Maybe you’d better tell it, Mog, since it’s really yours.”

I put down my teacup. “I’m not really sure where to start,” I said.

I told him the whole thing, more or less. As I told it, I began to feel a lot better, and Mr. Spintwice listened with complete attention. When I got to the bit about the camel, I pulled it out of its wrapping and passed it across to him. He spent the rest of the story examining it, turning it over and over in his hands, with a mystified expression on his little old face.

“It sounds,” he said, “as if you two are getting into deep waters. And over what? Over this?” He held up the camel by one of its legs. Lash, looking up from his cozy spot by the fire, got to his feet and trotted over to the dwarf’s chair, where he began sniffing at the camel much as he had done the night before.

“We wondered,” said Nick, “if you might tell us anything about it.”

“It’s brass,” Mr. Spintwice said simply. “Cheap. Tarnished. Made in a mold which must have made hundreds like it. The sort of trinket that comes from the Indies every time a ship puts in. As far as I can see it’s worth nothing at all: it doesn’t even have jewels for eyes, or anything like that. It’s a complete mystery why anyone would want it.” He began lifting it up and down, holding Lash’s head away with his other hand. “The only thing is,” he said, “its weight is all wrong.”

“What do you mean?” I asked, intrigued.

“Well,” he said, “it’s obviously not solid brass because it’s not heavy enough. So it must be hollow. But somehow …” he lifted it up and down a few more times, just to be sure, “it’s not light enough to be hollow, either.”

Nick stared at him, and then at me. “Of course!” he exclaimed. “It’s hollow!” He took the camel from the dwarf, and waved it. “What a pair of idiots we are!”

“What are you talking about?” I asked, still mystified.

“Don’t you understand? Look, we’ve been wondering for days why anyone would want to steal it, let alone threaten to kill for it. But it isn’t this they want. It’s something hidden inside it.” He shook it, but it didn’t rattle. “There must be something valuable inside,” he said, “and that’s why it feels too heavy to be hollow.”

The little jeweler began laughing and his eyes twinkled. “What a clever lad,” he chuckled, “he’s right, he’s quite right.”

Nick was turning the camel over and over furiously, looking for a way to get at whatever was inside. He pulled at the legs, scratched at it, tried twisting it around its hump. Suddenly he gave a cry. “The head comes off! Look!”

Grasping the drowsy-looking head in his grubby fist, he twisted it and it began to unscrew, squeaking, and sending little grains of powder trickling to the floor out of the grooves. Lash gave an excited bark.

“Well, I never,” said the dwarf, intrigued.

“You knew, didn’t you?” I exclaimed to Lash, remembering how he had tried to gnaw at its neck last night. Why hadn’t it occurred to me then?

“What on earth’s all this?” said Nick, “chalk?” He lifted off the head and blew. Powder flew up into his face, and he sneezed. “Or is it snuff?” He held it out to me. Lash was fussing around it, and I had to stand up so I could get a proper look without him pushing his nose inside.

The camel was full to the brim with an off-white powder, like flour and ashes.

“I don’t get it,” I said, “this powder can’t be valuable either. Let’s empty it, and see if there’s anything else in here.”

“All the powder,” put in the dwarf, “might just be there to stop the jewel, or whatever it is, from rattling about and getting scratched.” He passed me an old porcelain jar. “Empty it into here,” he said.

I stuffed the open neck into the jar and shook the camel. Clouds of powder rose as it all poured through. Lash, his ears erect, was transfixed, and kept giving short excited yelps as the stuff trickled out. We all watched eagerly for something else to fall into the jar — but no, just a steady stream of powder was all there was, until the camel was empty and the jar nearly full.

“Well,” said Spintwice, disappointed.

“This doesn’t make sense,” said Nick. “Are you sure there’s nothing else in there? Nothing’s stuck?”

I shook it, and pressed my eye to the open neck, but could see nothing.

“Let’s have some more tea,” Spintwice said, getting up.

But I was sitting with my nose in the neck of the jar. I sniffed.

“What are you doing?” Nick asked.

“I don’t know,” I said, “I think I’ve smelt this before.” I breathed in again.

Suddenly I felt very, very peculiar.

The jar was growing, swelling, like something about to give birth. I held it until it was too big for my hands and then I let it fall, which it did very slowly, as if it were falling through endless space. When I looked up, Nick and Mr. Spintwice had receded, the room suddenly expanding until it was the size of a cornfield: there they were, in their armchairs, miles away, moving their arms like insects, completely silent. Lash’s wet nose, shining in the glow of the fire, had become a disembodied ball of light, like a star. All I could hear was the ticking of the clocks, which became louder and louder until it was more like a rush of crashing echoes; the room began to spin and I clutched the arms of the chair in desperation as, lashing like a snake, the world flipped right over and threw me into a blaze of meaningless color, like the pinkest, bluest, blackest sunset that ever smeared its way across the smoky London sky.