As we left Spintwice’s I still felt rather strange; though at least the world was no longer expanding and contracting like a concertina. Nick and the dwarf had picked me up and sat me firmly in a chair, where they’d given me tea to drink, and then, as a further measure, brandy. Again I’d declined the offer of a bed for the night, partly out of a desire to protect Spintwice and partly because I had an aching feeling that, the more time I spent in his extraordinary and beguiling house, the less I’d ever want to go back to Cramplock’s at all, to work or to sleep. Bravely, Nick had agreed to come with me.

“Are you feeling better?” he asked as we walked up the street in the dark.

“I think so,” I said, hesitantly. “Nick, we can trust Spintwice, can’t we?”

“’Course we can,” he said quickly. “I tell him everything, Mog. I always have. He won’t say anything to anyone.”

The dwarf had been tremendously excited by the whole affair, and thought it was fun to join in our adventure; but I was worried. The tiny man wouldn’t present much of an obstacle if a murderous criminal should pay him a visit, determined to get at the camel or its contents. The more I thought about it, the less sure I was that we had done the right thing. I just hoped we’d hidden them well enough, and had been careful enough not to let anyone see us as we came and went.

“We’d better not hang around,” I said as we came to the corner where our routes home diverged.

Nick looked up at the dark sky. “I hope Pa’s still out,” he said, “and Ma Muggerage, too, for that matter. Then I can get back in without being clobbered. Look, I might come back here tomorrow and make sure Spintwice is all right.”

“Well, I shan’t come,” I said, “if you-know-who’s watching me, the further away I stay the better.” And as I hurried between the unfriendly walls towards home, every face which melted into the shadows at my approach made me stop in my tracks; every cough from a doorway, every murmur from a lighted window, even the rustle as Lash chased a rat into the shadows near my ankles, sent shivers up my spine; and by the time we got back I was running so fast I was completely out of breath.

“Busy today, Mog,” Cramplock told me next morning, “invitation cards for Lord Malmsey’s daughter’s wedding. I want you to cut the card while I engrave this coat of arms.” He was peering through his half-glasses at the design he’d been given to work from: a big shield-like coat of arms, featuring banners unfurled, and a motto in Latin I couldn’t understand. The emblems on the shield were three white flowers and a lion with a particularly blank expression on its face, as though its brain had been removed.

“A lion and three roses,” I said to Cramplock. “Does he like lions, then, this Lord Malmsey?”

“He doesn’t have to like lions,” Cramplock replied, “it’s a sign of courage.” He went to a cupboard and took out lots of little carving tools. “And the flowers are poppies, I think, not roses.”

A little bell rang.

“Customers, customers,” said Cramplock, laying down the pencil he’d just picked up. “Mustn’t discourage them, I suppose, but really I sometimes think I’d get on a great deal faster without them.”

“You’d be a great deal poorer, too,” I said, as he finished tapping a fat heap of stiff cards on their edges against the workbench to make them into a neat square pile. I couldn’t help being slightly suspicious of Cramplock this morning. Nick’s words of caution kept ringing in my ears. He did know more than he was saying, that much was certain; otherwise, what had that mysterious note been about? Cramplock put the cards down and went towards the door; but, as he saw who was waiting in the shop, his face changed.

“Mr. Glibstaff,” he said, slowly.

I felt a sudden sick misgiving. Glibstaff was a well-known local character: a small, smug, thoroughly unpleasant man who worked for the City Magistrates, and who saw it as his job to uphold justice and public order — which in practice meant he usually pokes his nose into everyone’s affairs to tell them what they should and shouldn’t be doing. I’d never met anyone with a good word to say about him: as far as I could tell he was completely untrustworthy, and used to threaten people with what he pompously referred to as “the Mysterious Might of the Law,” as though he were some kind of divine agent. People who didn’t do as he told them — or, more usually, didn’t pay him whatever money he fancied charging in return for leaving them alone — tended to find themselves summoned before the Magistrates and accused of some dreamt-up offense, for which they usually ended up paying out even more money in fines. Whatever course of action they chose, a visit from Mr. Glibstaff was usually expensive — and people greeted him in much the same way as they might greet someone who’d come to tell them their house had been condemned, or that all their investments had collapsed.

But my immediate thought was that someone had tipped Glibstaff off about my recent adventures. I hovered by the door, trying to eavesdrop on the conversation. I could see Glibstaff standing, rigid and officious, saying something to Cramplock, who had his back toward me. We have reason to believe, he’d be saying, one of your employees is a thief. I’d like to ask him some questions regarding a camel!

I chewed at my nails. The two men seemed to be deep in conversation. Could it have been Cramplock himself who had called Glibstaff in? Was the game up once and for all? The more I thought about it, the more panic-stricken I became. There would surely be some officers waiting at the back door too, and if I tried to run, I’d run straight into a trap. They were smoking me out like a badger! For an insane moment, I eyed the curved blade of the paper guillotine and began calculating whether my neck would fit underneath it.

Then I heard the shop door rattle shut. There was silence. He’d gone!

I couldn’t believe it.

Cramplock came back in. “Another job,” he said, reading something.

“A what?” I asked, as if I’d gone deaf with fear.

He looked up. “A murder notice,” he said. “We’ve got fifty to do by tomorrow. What’s the matter, Mog? You look rather — strange.”

“It’s all right, Mr. Cramplock,” I said, breathing more easily, “when I saw it was Glibstaff I, er — that is, I—”

He gave a short chuckle. “Well, for once his visit was for legitimate business reasons,” he said, handing me the sheet of paper Glibstaff had given him.

A REWARDis Offered to PERSONS supplyingInformation required by THE CROWN,concerning a most BRUTAL late

MURDERin the City of LONDON, being that ofone Wm Jiggs, Esq. Ships Chandler, ofFoulds Walk by Eastcheap on the Night of 20th May

Everything else melted away as I read this. For all I know, I might have been standing there for twenty-four hours.

“Mog? You look — even stranger than before,” Cramplock finally said.

“Oh,” I said, waking up, “er — it’s nothing, Mr. Cramplock.”

“I’m glad to hear it. Well, come on then, there’s work to be done.”

Nick’s face, when I told him, turned whiter than any of the paper we had in the shop. It was as though a little tap opened under his chin and all the blood surged away.

“When?” he hissed.

“Last night,” I said. “They found him in an abandoned hackney coach — no horse, no driver, just the cab and a dead Jiggs. Near the river, just under the north end of the bridge, it was.”

“How did he die?”

“It doesn’t say.” I reached inside my shirt for the poster I’d taken.

We were sitting in the Doll’s Head again; after I finished work I’d gone there with Lash and found Nick already sitting in the corner. As soon as he saw me, he’d known something was up. Now he sat reading the big poster, his eyes leaping up and down the page as though, like me, he couldn’t quite believe what he was seeing.

“I s’pose,” he said, slowly, “Coben could’ve done it. Maybe Jiggs was threatening to blow his cover, or something.” But it was clear he was thinking the same as I’d immediately thought. The single most likely murderer was the man who’d recently had an anonymous note, and who’d gone storming off in a rage the night before, believing Coben and Jiggs had taken his most precious possession.

The bosun. And it was all our fault.

“It was our note,” I said in a frantic whisper, “if we hadn’t written that rubbish with an eye drawn on it, thinking we were being so clever …”

“You can’t blame it on that,” Nick said, “he’d’ve suspected it was them anyway. They were the people that wanted it most, ‘cos they were the people he took it off in the first place.”

There was silence. Our minds were rattling with the possibilities.

“Coben will think I told someone,” I said. “Who else could’ve split? They were already after me for escaping from the chest.”

“But he thinks you’re me,” said Nick. “He’ll just think I’ve been doing Pa’s dirty work as usual, and that I told him where they were hiding.”

“Okay, so he’ll want to kill us both,” I hissed, agitated. “What are we going to do, Nick?”

“Look, don’t panic,” he said, doing a passable imitation of someone not panicking.

“Have you seen your Pa today?” I asked.

“No. I heard him go out early this morning.”

“Did you hear him come in last night?”

“Yep. He was with Ma Muggerage. They were drunk. They fell asleep straight away, far as I could tell.”

“Mrs. Muggerage must know, then,” I said. “D’you think they both did it? Together?” I pictured the awful pair advancing on the skinny and terrified Jiggs, backing him up against a wall in a dark alley near the river … the bosun’s arm flexed, with Mrs. Muggerage’s cleaver in his hand …

A man at a table nearby reached into his bag and pulled out a newspaper. I nudged Nick. We both watched him as he read, and tried to see what stories were on the front page. At one point he saw us straining to read the headlines.

“What do you two want?” he asked haughtily. “It ain’t polite, to read somebody else’s paper.”

“Sorry,” said Nick. “Look, Mog,” he continued in a loud voice, “that first one’s a D, and then there’s a A … I’m not sure what the next one is.” His eyes met those of the man again. “Been learnin’ to read, I have,” he told the man, with a proud face on.

“Sounds like you’re doing very well,” said the man, unsmilingly, and went back to his reading.

“What did you tell him that for?” I whispered.

“Make him think we can’t really read,” Nick said out of the corner of his mouth. “He might get suspicious otherwise. Do you know who he is?”

“No,” I whispered, “I’ve never seen him before.”

“There you are then,” Nick said, “he might be anybody! If he thinks we can’t read, he might not be so — careful.”

Eventually the man folded up his newspaper again, stuck it in his pocket, and rose to leave. He sidled past our table on his way out. “Good evening,” he said.

“Oh — evenin’,” Nick said, grinning stupidly.

“Evenin’,” I added. When I was sure he’d gone, I got up and went to the bar to ask Tassie if she knew who the man was.

“Can’t say I know, Maaster Mog,” she said, her brow furrowed. “But I seen him once or twice before. Has business in Leadenhall Street, I’ve heard ‘em say.”

“What makes you say that?” I asked, intrigued.

“Well, ‘s funny you should ask about him, ‘cos so did another customer a few days back. Just like you, Maaster Mog, started asking questions about ‘im the minute he’d gone. A regular conversation started in ‘ere, and I heard one man tell how he’d climbed into a cab outside and how he’d distinctly heard him give the instruction ‘Leadenhall Street’ to the driver. ‘S only a guess, though, Maaster Mog.”

Tassie was miraculous; nosy, but miraculous.

“That might be important,” I said to Nick quietly as I sat down, “did you hear what she said? Other people have been asking after him.”

“Leadenhall Street’s a long way off,” said Nick. “It’s near Spintwice’s. And he’s too smart-looking to live round here. So what’s he been doing in here in the first place?”

It was anybody’s guess, and I realized that Nick had been completely right to make sure we didn’t give too much away. I was anxiously trying to work out how much of our conversation he might have heard before we’d realized he was there.

“Well, anyway,” Nick said, “we can read that newspaper in peace now.”

“No,” I said, puzzled, “he took it with him. I saw him put it in his pocket before he went out.”

Nick placed a neatly folded newspaper on the table.

“Shocking, the number of thieves round here,” he said.

The item we were interested in took quite a lot of finding. It had a couple of column inches on page two.

Corpse Found in Abandoned Hackney Carriage

Carriage drivers in the City of London were questioned today over the discovery last night of a man’s body in a hackney carriage near Swan Stairs. The deceased has been identified from certain belongings about his person as Mr. William Jiggs of Foulds Walk by Eastcheap. Mr. Jiggs was an unmarried chandler. The authorities are pleading for testimony from witnesses who may have seen or spoken with Mr. Jiggs on the night of May 20th. A gentleman with a bandaged head, described by eyewitnesses as having been with the deceased early in the evening, is urgently sought. Mr. Jiggs is known to have been at the Three Friends Inn, Whitechapel, which he left on foot. The cause of his death is still uncertain as no marks of obvious violence have been found on the body.

“No marks of obvious violence?” I said, surprised. “They didn’t cut him up with a meat cleaver then.”

“Yeh, that’s the surprising bit,” Nick agreed. “You don’t think he was poisoned, do you? I wouldn’t have reckoned that was much in my Pa’s line.”

I read the column again, fascinated, trying to imagine the events which had led to Jiggs being left for dead in the carriage. “I suppose they followed him home from the Three Friends,” I said.

“He wasn’t going home,” Nick said, “not if he was found down by the river. I’ll tell you what I think. I think the murderers were disturbed. I’ll bet they did him in somewhere else, and were taking his body to the river to dump it. But for some reason they had to scarper and Jiggs was left in the cab.”

“How could they take a dead man in a cab without the driver getting suspicious?”

Nick laughed shortly. “You think most drivers wouldn’t just do what they were told, if someone like my Pa turned up in the middle of the night with a dead body over his shoulder and stuck a knife in their face?” he said.

“I wonder where Coben was,” I said. “I bet he’s lying low, knowing that stuff about a man with a bandage is all around town.”

“He’ll have taken it off,” said Nick. “And I shouldn’t be surprised if he’s halfway to France.”

There was a sudden clatter at the taproom door which made us both jump; and two of the regular customers, men I knew from another of the shops in the square, came bowling in good-naturedly. We greeted them as they strode over to talk to Tassie; and they stopped in their tracks.

“What have we here?” one of them asked. “Two peas in a pod! Well one of you is Mog Winter, but as sure as I’m standing here I can’t tell which.” And they laughed and pointed and generally drew attention to us for the whole of the next five minutes.

“I think we’d better stop going around together,” I said to Nick in a low voice. “Too many people have seen us already. It’s not safe to come here anymore. Tomorrow evening, if you can, meet me at the fountain.” This was close to Nick’s house, and sufficiently busy to make it a likely place for two lads to be seen without arousing suspicion. I got up to leave. “And keep your eye on the jeweller’s shop,” I said, “if anyone’s watching it, watch them!”

“I’ve done this before,” said Nick, “I’m all right. What are you going to do?”

“Keep my head down, I think.” I hitched up my pants and tugged at Lash’s lead to make him stand up. “See you tomorrow.”

“Mog,” he said.

I stopped in the doorway. He was sitting looking very small, with the enormous newspaper spread out in his lap.

“Be careful,” he said.

As I left the Doll’s Head I looked very carefully in every direction before deciding which way to go. Turning into the little narrow lane which was the quickest route home, I became aware, out of the corner of my eye, of something moving, a little way behind me. Constantly, during the last few days, I’d been convinced that eyes were watching me from every available window and from behind every corner. It crossed my mind, not for the first time, that someone might even have been watching me from the windows of the Doll’s Head itself. I’d toyed with the idea of asking Tassie exactly who she was letting rooms to at the moment — but I was wary of arousing even her suspicion. The fewer people who knew what we were mixed up in, the better.

When I turned my head, I could have sworn I saw someone disappearing behind a wall. I was definitely being followed. In that case, I thought, I’ll confuse them. Grasping Lash’s lead and drawing him close to my heels, I made up my mind to follow the most convoluted route home I could possibly devise; and I headed first down a path between red brick walls, leading in completely the wrong direction. On one side, the most ramshackle buildings in the whole parish leaked their effluent not only into the nearby Fleet ditch, but over the cobbles in the lane. In these ruins, with the white spire of St. James’s Church rising behind them, were hordes of people for whom London hadn’t found a use. This was where they nested, in a dense huddle, sleeping ten or twenty to a room — children alongside grown-ups, healthy people alongside ill people — in disgusting houses which had been here for centuries and which had fallen into such disrepair that they should really have been knocked down years ago. Every now and again, one of them would fall down: with no more warning than a sudden crescendo of creaking, it would just collapse, sending a cascade of dust and bricks and wooden beams out into the lane and leaving a hole between two houses like a gap in a mouth where a tooth had fallen out. Anyone unfortunate enough to be inside at the time would probably be killed among the collapsing rubble. Those who’d ventured out would return to find themselves with no where to live; and the process would start again, of finding another unsafe and squalid building into which to move themselves and their blinking, consumptive family. If their minds were agile enough, they might plot clever and violent crimes; and if their bodies had enough energy they might give a squalid existence to newly wailing little children beside whom the pinkest and baldest of rat-kittens stood a better chance of survival. There was no shortage of stories of people who’d gone down these lanes in the dark and never been seen again; and, in spite of my anxiety to get away from whoever it was who was following me, my heart was in my mouth at every street corner and I stopped each time, plucking up the courage to venture round the corner for fear of what I might find.

But what really frightened me was that I knew I was really no different from the people who lived here, and that if I’d been spilled out from my mother’s body onto dirty straw or old newspapers in one of these damp and stinking houses, I’d now be just the same. A cloth-wrapped bone-creature who made other children scared; a thin, jaundiced thing with sunken eyes and no understanding of anything but survival; a scarecrow.

It would be getting dark very soon, and by now I was pretty sure I’d shaken off my pursuer. I’d turned north and west and south and west again and doubled back on myself so many times I’d lost track of where I was. When we rounded the next corner we were suddenly in a familiar, much wider street into which the evening sunshine poured reassuringly, and I could see the unmistakable open space of Clerkenwell Green at the far end. Lash knew where he was now. We weren’t far from the back of Cramplock’s, and he struck out purposefully for home, practically dragging me behind him.

As we neared the square, I could hear something from one of the houses nearby. At first I thought it was a person singing, but after a couple of seconds’ listening I changed my mind. It was certainly music, of some kind, on an instrument which might have been a flute, or a bagpipe, but somehow didn’t quite sound like either.

Then I remembered the Irish tramp — who had talked in his own musical way about sounds like snakes. So he hadn’t been mad after all: as I stood listening to this convoluted, dizzying music I realized I was hearing exactly what he’d described. Extraordinary, rising and falling, twisting itself up in knots, it was somehow as different from normal music as the strange symbols on the man from Calcutta’s note were different from normal writing. Something about it reminded me of those unfathomable squiggles dangling from their line like knife-slashed washing. And I’d heard it somewhere before! Hadn’t I heard it, when I thought I was imagining things, locked up in Coben and Jiggs’s stolen chest?

Running now, along the lane toward the source of the music, I suddenly knew what I was going to find. And, sure enough, peering through the gates into the dingy backyards, I could tell it was coming from the mysterious empty house next door to Cramplock’s.

Lash was straining on his lead to get away.

“This way,” I said to him, tugging at the lead to try and rein him in. “Here, boy.”

He wouldn’t come anywhere near. No amount of trying would make him stay with me, and in the end I just let him go. “Home!” I said as he stood looking at me, at a distance of five or six paces, his head on one side. “Go home!”

He knew what that meant. Turning back to the high iron gate as he scampered off, I stood peering through for a few moments; and, taking a deep breath, I pushed it open.

I found myself venturing into a tiny and hopelessly overgrown little jungle of a garden, surrounded by high brick walls. The strange music now seemed to fill the hot evening air. A twisted old yew tree had clambered, over the years, all the way up the wall, forcing its branches in between the bricks. Ivy and creepers and swathes of big broad leaves clung to every surface. There was a constant drowsy hum of insects, and the heat of the evening and the encroaching vegetation made me feel as though I were suddenly somewhere else entirely, in a foreign country, and that London had somehow melted away completely. I felt very peculiar, as though I was no longer inhabiting my body but seeing myself standing there from the outside — much as I had done while locked in the chest at Coben’s, and last night at Spintwice’s after we’d opened up the camel. I remember thinking, dimly, how strange it was that I’d never even realized this garden existed: never even imagined there might be such a garden here.

Now the music faded away; and I came to my senses and ventured between the clinging plants to the little back door, listening for signs of activity inside. I couldn’t hear anything. I still felt dizzy as I pushed open the door, which swung away slowly and heavily on silent hinges.

It was quite dark, and I stood for a while allowing my eyes to adjust. But I didn’t see what I expected to see. I was in a low stairwell, with a set of wooden stairs leading upward ahead of me. The paneled walls seemed to lean at different angles, which made the whole place look a bit like an optical illusion. Dust floated passively in the late evening sunlight. The boards creaked as I ventured in; and as I peered into the little rooms, all of them apparently empty, I became more and more mystified.

I had been in here once before, and it hadn’t been like this. Defying Cramplock’s warnings, I’d ventured in here, a long time ago, and there had been nothing: no floors, no stairs, no paneling; simply a big, dark, burnt-out shell, with walls of bare blackened brick, and gnarled charred beams reaching across the empty space above my head where an upper floor had once been. I remembered it vividly.

Yet now there wasn’t a trace of fire damage to be seen. Someone must have been in here, rebuilding it — although there was no furniture, or any obvious sign of anyone actually living here.

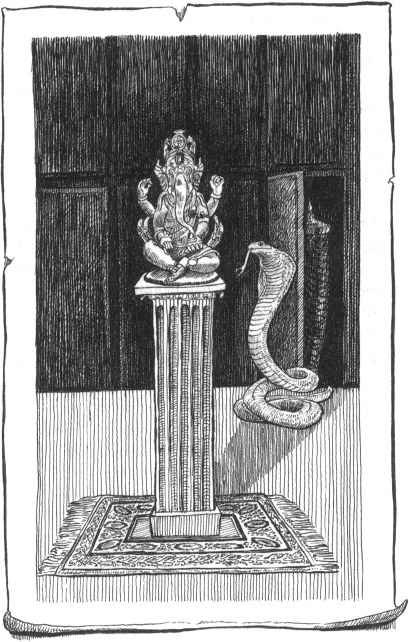

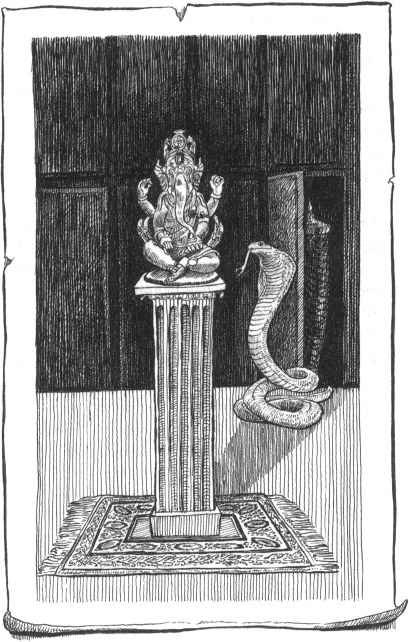

Without even realizing how scared the rest of me was, my feet began to take me slowly upstairs. There were three rooms leading off the landing, all of them as bare and empty as those downstairs: except that the walls of one of them were lined all around with solid oak panels from floor to ceiling. And right in the middle of the room, standing in a shaft of sunlight, there was a kind of pedestal: and, sitting upon it, at my eye level, a little statue.

I went over to it. It was made of brass, and seemed to be of a figure sitting cross-legged with his hands resting, palms upward, on his knees. As I looked at it more closely in the fading light, I noticed the face wasn’t that of a man, but of an elephant, with a trunk descending firmly down into its lap and two fine little tusks curving out on either side. In size, and in color, this little statue was very similar to the camel. I ran my fingers over the brass: over the little feet, over the folded robes. In the center of the forehead was a tiny, bright red jewel, shaped like a little teardrop.

The ruby, if that’s what it was, was picking up the light of the sinking sun through the window, and glowing with a rich, ethereal light. It looked like a single eye in the center of the elephant’s forehead. As I gazed into it, it seemed to glow more brightly, almost fiercely. I couldn’t stop looking at it.

I have you, it seemed to say. I am in control.

Momentarily, I felt dizzy again; then the light faded, as though the sun had gone behind a cloud or finally sunk below the horizon. My fingers played over the big flat forehead and the little bump the jewel made; and as I ran a forefinger down the smooth, tapering trunk I realized it was hinged, and could move.

Slipping my finger behind the trunk like the trigger of a gun, I pulled; and it sprang up with a sudden click to point upward so that the little elephant-man now seemed to be throwing up his trunk and trumpeting, silently enraged. To my alarm I heard a clatter somewhere behind the wall. I froze: I immediately assumed it must be someone coming in, but as I looked around the room I realized what the noise had been. I must have triggered a mechanism which opened a little trapdoor over by the far corner, in the oak paneling of the wall. I pushed the elephant’s trunk carefully back into place with my thumb, and went over to have a look.

When closed, the panel just looked like any other; but now it was hanging slightly open, at shoulder height, like a flap. Well, how could I resist lifting it to find out what was behind it? With the slightest of squeaks the little door swung up to reveal a secret compartment, about the height of a small adult and not much wider. A hiding place — not a very comfortable one, but big enough for a person to stand in. At first I thought it was empty; but, once my eyes had grown used to the darkness, I realized there was a big, urn-shaped wicker basket standing inside. Intrigued, I reached in and grasped the basket with both hands. It was lighter than I expected: but as I lifted off its lid, I could tell there was something in it.

I peered in. Whatever it was lay in the bottom, dark in color; not, at first sight, very big. What might it be? A piece of cloth? Something edible?

Then, slowly, with a long sinister rustle against the wickerwork, whatever it was moved.

It was something alive! There was just enough light to see it squirming in the bottom of the basket, disturbed by the sudden movement, waking up, rearing up a slender and lethal black head. In mingled panic and revulsion I shoved the wicker lid back on.

A snake. The snake! How could I have expected anything else? I had to get out of here.

But as I slipped back out of the secret compartment, I heard the unmistakable sound of a door handle being rattled below; and then slow footsteps, as someone stepped into the hallway and stopped at the bottom of the stairs. I was trapped.

As I looked around the room in a panic, I could hear the footsteps echoing relentlessly up the stairs towards me. There was only one possible place to hide.

Tears welled in my eyes as I crawled back into the secret hiding place. I shoved the snake basket as far forward as it would go, right up against the trapdoor, and pressed myself into the back of the cavity. I didn’t know which I was more terrified of: the man from Calcutta, or his snake, which I could even now hear slithering drily around inside the basket.

I held my breath in the darkness. Within seconds the footsteps coming through into the room, and I could do nothing but squeeze farther and farther back against the wall, praying he wouldn’t spot me. The grey light of dusk penetrated the hiding place as the flap was lifted open, and a pair of hands reached in and closed around the basket.

I braced myself and stood as rigidly still as I could, my heart pounding, praying I couldn’t be seen. A voice began speaking softly, in a foreign language, cooing as if the words were addressed to the snake. The basket was lifted carefully out through the flap; and as the voice continued to sing softly and I pressed myself tightly against the back of the compartment, the trapdoor swung shut, and clicked.

I opened my eyes. Complete darkness. The footsteps were receding, muffled now, thumping down the stairs. My blood was still pounding in my ears. I hadn’t been discovered, and the snake had gone — but now I was locked in. For at least a minute I didn’t move, my head reeling with the events of the past few minutes. When I did move, it was because I felt the wall of the compartment suddenly shifting behind me.

I tried to stand up, but I’d been leaning with my full weight back against the wall and it was collapsing. Before I had time to do anything about it, I had fallen through in a cascade of bricks, and was lying, grazed and dizzy, on my back in the dark.