WHAT IS THE felt experience of cognition at the moment one stands in the presence of a beautiful boy or flower or bird? It seems to incite, even to require, the act of replication. Wittgenstein says that when the eye sees something beautiful, the hand wants to draw it.

Beauty brings copies of itself into being. It makes us draw it, take photographs of it, or describe it to other people. Sometimes it gives rise to exact replication and other times to resemblances and still other times to things whose connection to the original site of inspiration is unrecognizable. A beautiful face drawn by Verrocchio suddenly glides into the perceptual field of a young boy named Leonardo. The boy copies the face, then copies the face again. Then again and again and again. He does the same thing when a beautiful living plant—a violet, a wild rose—glides into his field of vision, or a living face: he makes a first copy, a second copy, a third, a fourth, a fifth. He draws it over and over, just as Pater (who tells us all this about Leonardo) replicates—now in sentences—Leonardo’s acts, so that the essay reenacts its subject, becoming a sequence of faces: an angel, a Medusa, a woman and child, a Madonna, John the Baptist, St. Anne, La Gioconda. Before long the means are found to replicate, thousands of times over, both the sentences and the faces, so that traces of Pater’s paragraphs and Leonardo’s drawings inhabit all the pockets of the world (as pieces of them float in the paragraph now before you).

A visual event may reproduce itself in the realm of touch (as when the seen face incites an ache of longing in the hand, and the hand then presses pencil to paper), which may in turn then reappear in a second visual event, the finished drawing. This crisscrossing of the senses may happen in any direction. Wittgenstein speaks not only about beautiful visual events prompting motions in the hand but, elsewhere, about heard music that later prompts a ghostly sub-anatomical event in his teeth and gums. So, too, an act of touch may reproduce itself as an acoustical event or even an abstract idea, the way whenever Augustine touches something smooth, he begins to think of music and of God.

Beauty Prompts a Copy of Itself

The generation is unceasing. Beauty, as both Plato’s Symposium and everyday life confirm, prompts the begetting of children: when the eye sees someone beautiful, the whole body wants to reproduce the person. But it also—as Diotima tells Socrates—prompts the begetting of poems and laws, the works of Homer, Hesiod, and Lycurgus. The poem and the law may then prompt descriptions of themselves—literary and legal commentaries—that seek to make the beauty of the prior thing more evident, to make, in other words, the poem’s or law’s “clear discernibility” even more “clearly discernible.” Thus the beauty of Beatrice in La vita nuova requires of Dante the writing of a sonnet, and the writing of that one sonnet prompts the writing of another: “After completing this last sonnet I was moved by a desire to write more poetry.” The sonnets, in turn, place on Dante a new pressure, for as soon as his ear hears what he has made in meter, his hand wants to draw a sketch of it in prose: “This sonnet is divided into two parts …”; “This sonnet is divided into four parts.…”1

This phenomenon of unceasing begetting sponsors in people like Plato, Aquinas, Dante the idea of eternity, the perpetual duplicating of a moment that never stops. But it also sponsors the idea of terrestrial plenitude and distribution, the will to make “more and more” so that there will eventually be “enough.” Although very great cultural outcomes such as the Iliad or the Mona Lisa or the idea of distribution arise out of the requirement beauty places on us to replicate, the simplest manifestation of the phenomenon is the everyday fact of staring. The first flash of the bird incites the desire to duplicate not by translating the glimpsed image into a drawing or a poem or a photograph but simply by continuing to see her five seconds, twenty-five seconds, forty-five seconds later—as long as the bird is there to be beheld. People follow the paths of migrating birds, moving strangers, and lost manuscripts, trying to keep the thing sensorily present to them. Pater tells us that Leonardo, as though half-crazed, used to follow people around the streets of Florence once he got “glimpses of it [beauty] in the strange eyes or hair of chance people.” Sometimes he persisted until sundown. This replication in the realm of sensation can be carried out by a single perceiver across time (one person staring at a face or listening to the unceasing song of a mockingbird) or can instead entail a brief act of perception distributed across many people. When Leonardo drew a cartoon of St. Anne, for “two days a crowd of people of all qualities passed in naive excitement through the chamber where it hung.” This impulse toward a distribution across perceivers is, as both museums and postcards verify, the most common response to beauty: “Addis is full of blossoms. Wish you were here.” “The nightingale sang again last night. Come here as soon as you can.”

Beauty is sometimes disparaged on the ground that it causes a contagion of imitation, as when a legion of people begin to style themselves after a particular movie starlet, but this is just an imperfect version of a deeply beneficent momentum toward replication. Again beauty is sometimes disparaged because it gives rise to material cupidity and possessiveness; but here, too, we may come to feel we are simply encountering an imperfect instance of an otherwise positive outcome. If someone wishes all the Gallé vases of the world to sit on his own windowsills, it is just a miseducated version of the typically generous-hearted impulse we see when Proust stares at the face of the girl serving milk at a train stop:

I could not take my eyes from her face which grew larger as she approached, like a sun which it was somehow possible to stare at and which was coming nearer and nearer, letting itself be seen at close quarters, dazzling you with its blaze of red and gold.2

Proust wishes her to remain forever in his perceptual field and will alter his own location to bring that about: “to go with her to the stream, to the cow, to the train, to be always at her side.”

This willingness continually to revise one’s own location in order to place oneself in the path of beauty is the basic impulse underlying education. One submits oneself to other minds (teachers) in order to increase the chance that one will be looking in the right direction when a comet makes its sweep through a certain patch of sky. The arts and sciences, like Plato’s dialogues, have at their center the drive to confer greater clarity on what already has clear discernibility, as well as to confer initial clarity on what originally has none. They are a key mechanism in what Diotima called begetting and what Tocqueville called distribution. By perpetuating beauty, institutions of education help incite the will toward continual creation. Sometimes their institutional gravity and awkwardness can seem tonally out of register with beauty, which, like a small bird, has an aura of fragility, as when Simone Weil in Waiting for God writes:

The love of the beauty of the world … involves … the love of all the truly precious things that bad fortune can destroy. The truly precious things are those forming ladders reaching toward the beauty of the world, openings onto it.

But Weil’s list of precious things, openings into the world, begins not with a flight of a bird but with education: “Numbered among them are the pure and authentic achievements of art and sciences.”3 To misstate, or even merely understate, the relation of the universities to beauty is one kind of error that can be made. A university is among the precious things that can be destroyed.

Errors in Beauty: Attributes Evenly and Unevenly Present across Beautiful Things

The author of the Greater Hippias, widely believed to have been Plato, points out that while we know with relative ease what a beautiful horse or a beautiful man or possibly even a beautiful pot is (this last one is a matter of some dispute in the dialogue), it is much more difficult to say what “Beauty” unattached to any object is. At no point will there be any aspiration to speak in these pages of unattached Beauty, or of the attributes of unattached Beauty. But there are attributes that are, without exception, present across different objects (faces, flowers, birdsongs, men, horses, pots, and poems), one of which is this impulse toward begetting. It is impossible to conceive of a beautiful thing that does not have this attribute. The homely word “replication” has been used here because it reminds us that the benign impulse toward creation results not just in famous paintings but in everyday acts of staring; it also reminds us that the generative object continues, in some sense, to be present in the newly begotten object. It may be startling to speak of the Divine Comedy or the Mona Lisa as “a replication” since they are so unprecedented, but the word recalls the fact that something, or someone, gave rise to their creation and remains silently present in the newborn object.

In the case just looked at, then, the attribute was one common across all sites, and the error, when it briefly arose, involved seeing an imperfect version of the attribute (imitation of starlets or, more seriously, material greed) and correctly spotting the association with beauty, but failing to recognize the thousands of good outcomes of which this is a deteriorated version. Rejecting the imperfect version of the phenomenon of begetting makes sense; what does not make sense is rejecting the general impulse toward begetting, or rejecting the beautiful things for giving rise to false, as well as true, versions of begetting. To disparage beauty for the sake not of one of its attributes but simply for a misguided version of one of its otherwise beneficent attributes is a common error made about beauty.

But we will also see that many errors made about beauty arise not in relation to an attribute that is, without exception, common across all sites, but precisely in relation to attributes that are site-specific—that come up, for example, in relation to a beautiful garden but not in relation, say, to a beautiful poem; or come up in relation to beautiful persons but not in relation to the beauty of gods. The discontinuities across sites are the source of many confusions, one of which will be looked at in detail in Part Two. But the most familiar encounter with error occurs within any one site.

Errors within Any One Site

It seems a strange feature of intellectual life that if you question people—“What is an instance of an intellectual error you have made in your life?”—no answer seems to come readily to mind. Somewhat better luck is achieved if you ask people (friends, students) to describe an error they have made about beauty. It may be helpful if, before proceeding, the reader stops and recalls—in as much detail as possible—an error he or she has made so that another instance can be placed on the page in conjunction with the few about to be described. It may be useful to record the error, or the revision, in as much detail as is possible because I want to make claims here about the way an error presents itself to the mind, and the accuracy of what I say needs alternative instances to be tested against. The error may be a misunderstanding in the reading of Schiller’s “Ninth Letter” in his Aesthetic Education of Man, or a misreading of page eleven in Kant’s Third Critique. But the question is more directly aimed at errors, and revisions, that have arisen in day-to-day life. In my own case, for example, I had ruled out palm trees as objects of beauty and then one day discovered I had made a mistake.

Those who remember making an error about beauty usually also recall the exact second when they first realized they had made an error. The revisionary moment comes as a perceptual slap or slam that itself has emphatic sensory properties. Emily Dickinson’s poem—

It dropped so low—in my Regard—

I heard it hit the Ground—

is an instance. A correction in perception takes place as an abrasive crash. Though it has the sound of breaking plates, what is shattering loudly is the perception itself:

It dropped so low—in my Regard—

I heard it hit the Ground—

And go to pieces on the Stones

At bottom of my mind—4

The concussion is not just acoustic but kinesthetic. Her own brain is the floor against which the felt impact takes place.

The same is true of Shakespeare’s “Lilies that fester smell far worse than weeds.” The correction, the alteration in the perception, is so palpable that it is as though the perception itself (rather than its object) lies rotting in the brain. In both cases, the perception has undergone a radical alteration—it breaks apart (as in breaking plates) or disintegrates (as in the festering flower); and in both cases, the alteration is announced by a striking sensory event, a loud sound, an awful smell. Even if the alteration in perception were registered not as the sudden introduction of a negative sensation but as the disappearance of the positive sensory attributes the thing had when it was beautiful, the moment might be equally stark and highly etched. Gerard Manley Hopkins confides calmly, cruelly, to someone he once loved that his love has now almost disappeared. He offers as a final clarifying analogy what happens when a poem, once held to be beautiful, ceases to be so:

Is this made plain? What have I come across

That here will serve me for comparison?

The sceptic disappointment and the loss

A boy feels when the poet he pores upon

Grows less and less sweet to him, and knows no cause.

No loud sound or bad smell could make this more devastating. But why? In part, because what is so positive is here being taken away: sweet is a taste, a smell, a sound—the word, of all words, closest to the fresh and easy call of a bird; and conveying a belovedness, an acuity of regard, as effortless and unasked-for as honeysuckle or sweet william. Fading (one might hope) could conceivably take place as a merciful numbing, a dulling, of perception, or a turning away to other objects of attention. But the shades of fading here take place under the scrutiny of bright consciousness, the mind registering in technicolor each successive nuance of its own bereavement. Hopkins’s boy, with full acuity, leans into, pores upon, the lesson and the lessening.

Those who recall making an error in beauty inevitably describe one of two genres of mistake. The first, as in the lines by Dickinson, Shakespeare, and Hopkins, is the recognition that something formerly held to be beautiful no longer deserves to be so regarded. The second is the sudden recognition that something from which the attribution of beauty had been withheld deserved all along to be so denominated. Of these two genres of error, the second seems more grave: in the first (the error of overcrediting), the mistake occurs on the side of perceptual generosity, in the second (the error of undercrediting) on the side of a failed generosity. Doubting the severity of the first genre of error does not entail calling into question the pain the person feels in discovering her mistake: she has lost the beautiful object in the same way as if it had remained beautiful but had suddenly moved out of her reach, leaving her stranded, betrayed; in actuality, the faithful object has remained within reach but with the subtraction of all attributes that would ignite the desire to lay hold of it. By either path the desirable object has vanished, leaving the brain bereft.

The uncompromising way in which errors in beauty make themselves felt is equally visible in the second, more severe genre of intellectual error, where something not regarded as beautiful suddenly alerts you to your error. A better description of the moment of instruction might be to say—“Something you did not hold to be beautiful suddenly turns up in your arms arrayed in full beauty”—because the force and pressure of the revision is exactly as though it is happening one-quarter inch from your eyes. One lets things into one’s midst without accurately calculating the degree of consciousness required by them. It is as though, when you were about to walk out onto a ledge, you had contracted to carry something, and only once out on the precipice did you realize that the object weighed one hundred pounds.

How one walks through the world, the endless small adjustments of balance, is affected by the shifting weights of beautiful things. Here the alternatives posed a moment ago about the first genre of error—where the beautiful object vanished, not because the still-beloved object itself disappeared carrying its beauty with it, but because the object stayed behind with its beauty newly gone—are reversed. In the second genre of error a beautiful object is suddenly present, not because a new object has entered the sensory horizon bringing its beauty with it (as when a new poem is written or a new student arrives or a willow tree, unleafed by winter, becomes electric—a maze of yellow wands lifting against lavender clapboards and skies) but because an object, already within the horizon, has its beauty, like late luggage, suddenly placed in your hands. This second genre of error entails neither the arrival of a new beautiful object, nor an object present but previously unnoticed, but an object present and confidently repudiated as an object of beauty.

My palm tree is an example. Suddenly I am on a balcony and its huge swaying leaves are before me at eye level, arcing, arching, waving, cresting and breaking in the soft air, throwing the yellow sunlight up over itself and catching it on the other side, running its fingers down its own piano keys, then running them back up again, shuffling and dealing glittering decks of aqua, green, yellow, and white. It is everything I have always loved, fernlike, featherlike, fanlike, open—lustrously in love with air and light.

The vividness of the palm states the acuity with which I feel the error, a kind of dread conveyed by the words “How many?” How many other errors lie like broken plates or flowers on the floor of my mind? I pore over the floor but cannot see much surface since all the space is taken up by the fallen tree trunk, the big clumsy thing with all its leaves stuffed into one shaft. But there may be other things down under there. When you make an error in beauty, it should set off small alarms and warning lights. Instead it waits until you are standing on a balcony for the flashing sword dance to begin. Night comes and I am still on the balcony. Under the moonlight, my palm tree waves and sprays needles of black, silver, and white; hundreds of shimmering lines circle and play and stay in perfect parallel.

Because the tree about which I made the error was not a sycamore, a birch, a copper beech, a stellata Leonard magnolia but a palm tree, because in other words it was a tree whose most common ground is a hemisphere not my own (southern rather than northern) or a coast not my own (west rather than east), the error may seem to be about the distance between north and south, east and west, about mistakes arising from cultural difference. Sometimes the attribution of a mistake to “cultural difference” is intended to show why caring about beauty is bad, as though if I had attended to sycamores and chestnuts less I might have sooner seen the palminess of the palm, this green pliancy designed to capture and restructure light. Nothing I know about perception tells me how my love of the sycamore caused, or contributed to, my failure to love the palm, since there does not appear to be, inside the brain, a finite amount of space given to beautiful things that can be prematurely filled, and since attention to any one thing normally seems to heighten, rather than diminish, the acuity with which one sees the next. Still, it is the case that if I were surrounded every day by hundreds of palms, one of them would have sooner called upon me to correct my error.

Beauty always takes place in the particular, and if there are no particulars, the chances of seeing it go down. In this sense cultural difference, by diminishing the number of times you are on the same ground with a particular vegetation or animal or artwork, gives rise to problems in perception, but problems in perception that also arrive by many other paths. Proust, for example, says we make a mistake when we talk disparagingly or discouragingly about “life” because by using this general term, “life,” we have already excluded before the fact all beauty and happiness, which take place only in the particular: “we believed we were taking happiness and beauty into account, whereas in fact we left them out and replaced them by syntheses in which there is not a single atom of either.” Proust gives a second instance of a synthetic error:

So it is that a well-read man will at once begin to yawn with boredom when one speaks to him of a new “good book,” because he imagines a sort of composite of all the good books that he has read, whereas a good book is something special, something unforeseeable, and is made up not of the sum of all previous masterpieces but of something which the most thorough assimilation … would not enable him to discover.

Here the error arises not from cultural difference—the man is steeped in books (and steeped in life)—but from making a composite of particulars, and so erasing the particulars as successfully as if he lived in a hemisphere or on a coast that grew no books or life.

When I used to say the sentence (softly and to myself) “I hate palms” or “Palms are not beautiful; possibly they are not even trees,” it was a composite palm that I had somehow succeeded in making without even ever having seen, close up, many particular instances. Conversely, when I now say, “Palms are beautiful,” or “I love palms,” it is really individual palms that I have in mind. Once when I was under a high palm looking up at its canopy sixty feet above me, its leaves barely moving, just opening and closing slightly as though breathing, I gradually realized it was looking back down at me. Stationed in the fronds, woven into them, was a large owl whose whole front surface, face and torso, was already angled toward the ground. To stare down at me, all she had to do was slowly open her eyes. There was no sudden readjustment of her body, no alarmed turning of her head—her sleeping posture, assumed when she arrived each dawn in her palm canopy, already positioned her to stare down at anyone below, simply by rolling open her eyes in a gesture as pacific as the breezy breathings of the canopy in which she was nesting. I normally think of birds nesting in cuplike shapes where the cup is upwards, open to the sky, but this owl (and I later found other owls entering other palms at dawn) had discovered that the canopy was itself a magnified nest, only it happened to be inverted so that it cupped downward. By interleaving her own plumage with the palm’s, latching herself into the leaves, she could hold herself out over the sixty-foot column of air as though she were still flying. It was as though she had stopped to sleep in midair, letting the giant arcing palm leaves take over the work of her wings, so that she could soar there in the shaded sunshine until night came and she was ready to fly on her own again.

Homer sings of the beauty of particular things. Odysseus, washed up on shore, covered with brine, having nearly drowned, comes upon a human community and one person in particular, Nausicaa, whose beauty simply astonishes him. He has never anywhere seen a face so lovely; he has never anywhere seen any thing so lovely. “No, wait,” he says, oddly interrupting himself. Something has suddenly entered his mind. Here are the lines:

But if you’re one of the mortals living here on earth,

three times blest are your father, your queenly mother,

three times over your brothers too. How often their hearts

must warm with joy to see you striding into the dances—

such a bloom of beauty. [ .… ]

I have never laid eyes on anyone like you,

neither man nor woman …

I look at you and a sense of wonder takes me. Wait,

once I saw the like—in Delos, beside Apollo’s altar—

the young slip of a palm-tree springing into the light.

There I’d sailed, you see, with a great army in my wake,

out on the long campaign that doomed my life to hardship.

That vision! Just as I stood there gazing, rapt, for hours …

no shaft like that had ever risen up from the earth—

so now I marvel at you, my lady: rapt, enthralled,

too struck with awe to grasp you by the knees

though pain has ground me down.5

Odysseus’s speech makes visible the structure of perception at the moment one stands in the presence of beauty. The beautiful thing seems—is—incomparable, unprecedented; and that sense of being without precedent conveys a sense of the “newness” or “newbornness” of the entire world. Nausicaa’s childlike form, playing ball on the beach with her playmates, reinforces this sense. But now something odd and delicately funny happens. Usually when the “unprecedented” suddenly comes before one, and when one has made a proclamation about the state of affairs—“There is no one like you, nothing like this, anywhere”—the mind, despite the confidently announced mimesis of carrying out a search, does not actually enter into any such search, for it is too exclusively filled with the beautiful object that stands in its presence. It is the very way the beautiful thing fills the mind and breaks all frames that gives the “never before in the history of the world” feeling.

Odysseus startles us by actually searching for and finding a precedent; then startles us again by managing through that precedent to magnify, rather than diminish, his statement of regard for Nausicaa, letting the “young slip of a palm-tree springing into the light” clarify and verify her beauty. The passage continually restarts and refreshes itself. Three key features of beauty return in the new, but chronologically prior, object of beauty.

First, beauty is sacred. Odysseus had begun (in lines earlier than those cited above) with the intuition that in standing before Nausicaa he might be standing in the presence of Artemis, and now he rearrives at that intuition, since the young palm grows beside the altar of Delos, the birthplace of Apollo and Artemis. His speech says this: If you are immortal, I recognize you. You are Artemis. If instead you are mortal, I am puzzled and cannot recognize you, since I can find no precedent. No, wait. I do recognize you. I remember watching a tree coming up out of the ground of Delos.

Second, beauty is unprecedented. Odysseus believes Nausicaa has no precedent; then he recalls the palm and recalls as well that the palm had no precedent: “No shaft like that had ever risen up from the earth.” The discovery of a precedent only a moment ago reported not to exist contradicts the initial report, but at the same time it confirms the report’s accuracy since the feature of unprecedentedness stays stable across the two objects. Nausicaa and the palm each make the world new. Green, pliant, springing up out of the ground before his eyes, the palm is in motion yet stands firm. So, too, Nausicaa: she plays catch, runs into the surf, dances an imagined dance before her parents and brothers, yet stands firm. When the naked Odysseus suddenly comes lurching out onto the sand, “all those lovely girls … scattered in panic down the jutting beaches. / Only Alcinous’ daughter held fast … and she firmly stood her ground and faced Odysseus.”

These first and second attributes of beauty are very close to one another, for to say that something is “sacred” is also to say either “it has no precedent” or “it has as its only precedent that which is itself unprecedented.” But there is also a third feature: beauty is lifesaving. Homer is not alone in seeing beauty as lifesaving. Augustine described it as “a plank amid the waves of the sea.”6 Proust makes a version of this claim over and over again. Beauty quickens. It adrenalizes. It makes the heart beat faster. It makes life more vivid, animated, living, worth living. But what exactly is the claim or—more to the point—exactly how literal is the claim that it saves lives or directly confers the gift of life? Neither Nausicaa nor the palm rescues Odysseus from the sea, but both are objects he sees immediately after having escaped death. Odysseus stands before Nausicaa still clotted with matter from the roiling ocean that battered him throughout Book 5, just as Odysseus stood before the young palm having just emerged out of the man-killing sea: “There I’d sailed, you see, with a great army in my wake, / out on the long campaign that doomed my life to hardship.” Here again Homer re-creates the structure of a perception that occurs whenever one sees something beautiful; it is as though one has suddenly been washed up onto a merciful beach: all unease, aggression, indifference suddenly drop back behind one, like a surf that has for a moment lost its capacity to harm.

Not Homer alone but Plato, Aquinas, Plotinus, Pseudo-Dionysius, Dante, and many others repeatedly describe beauty as a “greeting.” At the moment one comes into the presence of something beautiful, it greets you. It lifts away from the neutral background as though coming forward to welcome you—as though the object were designed to “fit” your perception. In its etymology, “welcome” means that one comes with the well-wishes or consent of the person or thing already standing on that ground. It is as though the welcoming thing has entered into, and consented to, your being in its midst. Your arrival seems contractual, not just something you want, but something the world you are now joining wants. Homer’s narrative enacts the “greeting.”7 Odysseus hears Nausicaa even before he sees her. Her voice is green: mingling with the voices of the other children, it sounds like water moving through lush meadow grass. This greenness of sound becomes the fully articulated subject matter of her speech when she later directs him through her father’s groves, meadows, blossoming orchards, so he can reach their safe inland hall, where the only traces of the ocean are the lapis blue of the glazed frieze on the wall and the “sea-blue wool” that Nausicaa’s mother continually works. Nausicaa’s beauty, her welcoming countenance, allows Odysseus to hope that he will be made welcome in “the welcome city,” “welcome Scheria”—that “generous King Alcinous” and the Phaeacian assembly will receive him, as in fact they do, with “some mercy and some love.”

Odysseus has made a hymn to beauty. One may protest that this description tonally overcredits Odysseus since—something that has so far not been mentioned—Odysseus is here being relentlessly strategic. He has a concrete, highly instrumental goal. He must get Nausicaa to lead him to safety. The lines immediately preceding his hymn of praise show him “slyly” calculating how to approach her. How should he walk? Stand? Speak? Should he hold himself upright or kneel on the ground before her? Should he grasp her by the knees or keep his distance, stand reverently back? But just as his hymn to beauty can be seen as an element subordinate to the larger frame of his calculation for reentering the human community, so the narrative of calculation can be seen as subordinate to the hymn of beauty. The moment of coming upon something or someone beautiful might sound—if lifted away from Odysseus’s own voice and arriving from a voice outside him—like this: “You are about to be in the presence of something life-giving, lifesaving, something that deserves from you a posture of reverence or petition. It is not clear whether you should throw yourself on your knees before it or keep your distance from it, but you had better figure out the right answer because this is not an occasion for carelessness or for leaving your own postures wholly to chance. It is not that beauty is life-threatening (though this attribute has sometimes been assigned it), but instead that it is life-affirming, life-giving; and therefore if, through your careless approach, you become cut off from it, you will feel its removal as a retraction of life. You will fall back into the sea, which even now, as you stand there gazing, is only a few feet behind you.” The framework of strategy and deliberation literalizes, rather than undermines, the claim that beauty is lifesaving.

Sacred, lifesaving, having as precedent only those things which are themselves unprecedented, beauty has a fourth feature: it incites deliberation. I have spoken of Odysseus’s error toward Nausicaa. But one could just as easily see Odysseus’s error as committed against the palm: seeing Nausicaa, he temporarily forgets the palm by the altar, injuring it by his thoughtless disregard and requiring him at once to go on to correct himself. The hymn to Nausicaa’s beauty can instead be called a palinode to the beauty of the palm. By either account, Odysseus starts by making an error.

So far error has been talked about as a cognitive event that just happens to have beauty—like anything else—as one of its objects. But that description, which makes error independent of beauty, may itself be wrong. The experience of “being in error” so inevitably accompanies the perception of beauty that it begins to seem one of its abiding structural features. On the one hand, something beautiful—a blossom, a friend, a poem, a sky—makes a clear and self-evident appearance before one: this feature can be called “clear discernibility” for reasons that will soon be elaborated. The beauty of the thing at once fills the perceiver with a sense of conviction about that beauty, a wordless certainty—the this! here! of Rilke’s poetry. On the other hand, the act of perceiving that seemingly self-evident beauty has a built-in liability to self-correction and self-adjustment, so much so that it appears to be a key element in whatever beauty is. This may explain why, as noticed earlier, when the informal experiment is conducted of asking people about intellectual errors, they do not readily remember ever having made one (or, more accurately, they are sure they have made one but do not happen to remember what it is); whereas when you ask them about errors in beauty, they seem not only to remember one but to recall the process of correction in vivid sensory detail. Something beautiful immediately catches attention yet prompts one to judgments that one then continues to scrutinize, and that one not infrequently discovers to be in error.

Something beautiful fills the mind yet invites the search for something beyond itself, something larger or something of the same scale with which it needs to be brought into relation. Beauty, according to its critics, causes us to gape and suspend all thought. This complaint is manifestly true: Odysseus does stand marveling before the palm; Odysseus is similarly incapacitated in front of Nausicaa; and Odysseus will soon, in Book 7, stand “gazing,” in much the same way, at the season-immune orchards of King Alcinous, the pears, apples, and figs that bud on one branch while ripening on another, so that never during the cycling year do they cease to be in flower and in fruit. But simultaneously what is beautiful prompts the mind to move chronologically back in the search for precedents and parallels, to move forward into new acts of creation, to move conceptually over, to bring things into relation, and does all this with a kind of urgency as though one’s life depended on it. So distinct do the two mental acts appear that one might believe them prompted by two different species of beauty (as Schiller argued for the existence of both a “melting” beauty and an “energetic” beauty)8 if it weren’t for the fact that they turn up folded inside the same lyric event, though often opening out at chronologically distinct moments.

One can see why beauty—by Homer, by Plato, by Aquinas, by Dante (and the list would go on, name upon name, century by century, page upon page, through poets writing today such as Gjertrud Schnackenberg, Allen Grossman, and Seamus Heaney)—has been perceived to be bound up with the immortal, for it prompts a search for a precedent, which in turn prompts a search for a still earlier precedent, and the mind keeps tripping backward until it at last reaches something that has no precedent, which may very well be the immortal. And one can see why beauty—by those same artists, philosophers, theologians of the Old World and the New—has been perceived to be bound up with truth. What is beautiful is in league with what is true because truth abides in the immortal sphere. But if this were the only basis for the association, then many of us living now who feel skeptical about the existence of an immortal realm might be required to conclude that beauty and truth have nothing to do with one another. Luckily, a second basis for the association stands clearly before us: the beautiful person or thing incites in us the longing for truth because it provides by its compelling “clear discernibility” an introduction (perhaps even our first introduction) to the state of certainty yet does not itself satiate our desire for certainty since beauty, sooner or later, brings us into contact with our own capacity for making errors. The beautiful, almost without any effort of our own, acquaints us with the mental event of conviction, and so pleasurable a mental state is this that ever afterwards one is willing to labor, struggle, wrestle with the world to locate enduring sources of conviction—to locate what is true. Both in the account that assumes the existence of the immortal realm and in the account that assumes the nonexistence of the immortal realm, beauty is a starting place for education.

Hymn and palinode—conviction and consciousness of error—reside inside most daily acts of encountering something beautiful. One walks down a street and suddenly sees a redbud tree—its tiny heart-shaped leaves climbing out all along its branches like children who haven’t yet learned the spatial rules for which parts of the playground they can run on. (Don’t they know they should stay on the tips of the twigs?) It is as though one has just been beached, lifted out of one ontological state into another that is fragile and must be held onto lest one lose hold of the branch and fall back into the ocean. Like Odysseus, one feels inadequate to it, lurches awkwardly around it, saying odd things to the small leaves, wishing to sing to them a hymn or, finding oneself unable, wishing in apology to make a palinode. Perhaps like Dante watching Beatrice, one could make a sonnet and then a prose poem explaining the sonnet; or, like Leonardo looking at a violet, one could make a sketch, then another, then another; or like Lady Autumn, listening with amazement to a stanza Keats has just sung her, one could sit there patiently staring moment after moment, hour by hour. Homer was right: beauty is lifesaving (or life-creating as in Dante’s title La vita nuova, or life-altering as in Rilke’s imperative “You must change your life”). And Homer was right: beauty incites deliberation, the search for precedents. But what about the immortal, about which Homer may or may not have been right? If we look at modern examples of the palinode for a missing precedent, does the plenitude and aspiration for truth stay stable, even if the metaphysical referent is in doubt?

Matisse never hoped to save lives. But he repeatedly said that he wanted to make paintings so serenely beautiful that when one came upon them, suddenly all problems would subside. His paintings of Nice have for me this effect. My house, though austere inside, is full of windows banking onto a garden. The garden throws changing colors into the chaste rooms—lavenders, pinks, blues, and pools of green. One winter when I was bereft because my garden was underground, I put Matisse prints all over the walls—thirteen in a single room. All winter long I applied the paintings to my staring eyes, and now they are, in retrospect, one of the things that make my former disregard of palm trees so startling. The precedent behind each Nice painting is the frond of a palm; or, to be more precise, each Nice painting is a perfect cross between an anemone flower and a palm frond. The presence of the anemone I had always seen—in the mauve and red colors, the abrupt patches of black, in the petal-like tissue of curtains, slips, parasols, and tablecloths, in the small pools of color with sudden drop-offs at their edges. But I completely missed what resided behind these surfaces, what Odysseus would have seen, the young slip of a palm springing into the light.

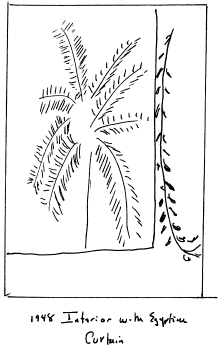

The signature of a palm is its striped light. Palm leaves stripe the light. The dyadic alternations of leaf and air make the frond shimmer and move, even when it stays still, and if there is an actual breeze, then the stripings whip around without ever losing their perfect alignment across the full sequence. Matisse transcribes this effect to many of the rooms in the Nice paintings. Here is the structure of one entitled Interior, Nice, Seated Woman with a Book, where the arcings and archings of the fronds are carried in the rounding curves of the curtain and chair and woman. The striped leaf-light is everywhere in the room, in the louvered slats of the slanted window, in the louvered slats of the straight window, in the louvered slats reflecting in the glass window, in the striped blue-and-white cloth on the lower right and its mirrored echo, in the woman’s striped robe, lifting out from its center like an array of fronds from a stalk, and in the large bands of color in the architectural features of the room. On the upper left, lifting high above the woman, a single curved frond cups outward, its red, blue, and green leaf colors setting the palette for the rest of the room: it registers the botanical precedent, in case the small surface of the actual black-green palm (visible in the upper half of the window and indicated in my sketch by dark ink) is missed. Light trips rapidly across the surface of the room: in out in, out in out in, out off on off, on out off in, on off on off. It feathers across the eye, excites it, incites in it saccadic leaps and midair twirls (“retinal arabesques,” my friend calls them). It is as though the painting were painted with the frond of a palm, or as though the frond were just laid down on the canvas, as though it swished across the canvas, leaving prints of itself here there here there here there.

In My Room at the Beau Rivage, the striping, the stationary equivalent of shimmering, is accomplished through the pink-and-yellow wallpaper stripes and the curved lines of the satin chair, where the leaf-light is so concentrated it simply whites out in one section. The pliant chair, like the woman in Seated Woman with a Book, is the newborn palm tree, the place where light pools and then spills outward in all directions. Like silver threads appearing and disappearing behind the cross threads of a weaving—not a finished weaving but one whose making is just now under way—the silver jumps of our eyes trip in unison across the stripes, appearing and disappearing beneath the latticing of the guide threads. It is as though white sea-lanes have been drawn on the surface of the ocean and across them Nereids dive in and out.

Missing the print of the palm seems remarkable. The thing so capaciously and luminously dispersed throughout the foreground of the room is concretely specified at the very back of (almost as if behind) the painting. The palm is present in all, or almost all, of the Nice paintings. But the amount of surface that is dedicated to the actual tree, as opposed to the palmy offspring stripings inside the room, is tiny—one-thirtieth of the canvas in Seated Woman with a Book, one-fiftieth of the canvas in My Room at the Beau Rivage, and similar small fractions in others of the 1920s, such as The Morning Tea, Woman on a Sofa, Still Life: ‘Les Pensées de Pascal,’ Vase of Flowers in Front of the Window, in each of which the tree occupies between one-fiftieth and one sixty-third of the full surface.

Further, the tree’s individuated fronds are themselves seldom visible, and the leaves, never. A curtain may be striped; a wall may be striped; a bowl of flowers may be striped; a floor may be striped; a human figure may be striped; a table, bed, or chair may be striped. The fronds are the one thing to which stripes are disallowed, except perhaps in “Les Pensées de Pascal” where (on close inspection of the very small tree) the green branchings have a cupped pink underside that sets in motion, inside the room, the soft blocks of gray and pink where the curtain overlaps the windowsill, and the hot pink and gray stripes on the sill below. More typically the tree canopy looks like a knob of broccoli, sometimes lacks a trunk, and may even be positioned in the lower half of the painting. It provides just a fleeting acknowledgment of the fact that it is the precedent that sets in motion all the light-filled surfaces in the foreground. The tree is the only thing in the paintings to which the palm-style is not applied, just as when Matisse includes a bowl of actual anemones or nasturtiums or fritillarias in his paintings, it is often the one thing to which the anemone-style, nasturtium-style, or fritillaria-style (everywhere else filling the room) will be disallowed.

But at least one painting from the Nice period—The Painter and His Model, Studio Interior (1919)—explicitly announces the fact that the palm frond is the model from which, or more accurately the instrument with which, Matisse paints. Perhaps the palm is here openly saluted and seized because the painting is overtly about the act of painting. The room is full of sunlight. Yellow. Cream. Gold. White. These colors cover two-thirds of its surface, which is also awash with lavenders and reds falling in sun-filled stripes from the curtains, the walls, the man, the table, the chair, the dresser. The palm in the window is still only a small fraction of the surface, one thirty-fifth, but unlike many other Nice paintings, it is here stark, self-announcing. The palm now has emphatic fronds. It is brown, like the painter’s brush, which has only a shaft and no brush, and so seems supplied by the tree, as though the palm were a continuation of the tool he holds, interrupted by the woman’s body (the woman who is technically the model referred to in the title, though the palm seems more model than she). The palm seems not just the model, the thing that inspires him or the thing he aspires to copy, but much more material in its presence. It is what he reaches out for, closes his hand around, and presses down on the surface of the canvas he is lashing with light. It is a graphic literalization of “brush,” “to brush,” a brush with beauty. Because the palmy stripings incite the silver cross-jumps of light over our face and eyes, it is as though the painting in turn paints us, plaiting braids of light across the surface of our skin.

Other Nice paintings depicting the act of composition similarly register the palm as instrument. The woman painter in The Morning Session (1924) wears a yellow-and-black striped dress that covers her torso, lap, and legs—the vertical stripes become horizontal when they reach her lap, raying out like sunlight before becoming vertical again as they turn at her knees and drop to the floor. She sits in front of a red-and-white striped wall, and long vertical bands of peach streak down the window, down the walls, and down the back of her painting. Because of the angle at which she sits, the brush with which she paints (like the man’s in The Painter and His Model) has only a shaft and no brush, but by good luck there stand directly above her hand the open fronds, the luxurious canopy brush, of a distant palm. This vision of creation extends to auditory composition. The musician’s bow in Young Woman Playing the Violin in Front of the Open Window (1923) is also completed and continued by the fronds of the palm outside her window, turning her bow into a brush. She is safely held in the lap of the striped walls on three sides. Above her head, the huge open window—open sky, open sea, open sail, open palm—seems the picture of the airy music she is playing, a picture painted with the brush of her bow.

Three decades later, Matisse still paints palms in windows, but now as the fulsome, fully saluted precedent. The pictures seem Odyssean palinodes to the once insufficiently acknowledged tree. By 1947 the palm fills not one sixty-third or one-fiftieth or one-thirtieth of the painting but one-quarter. By 1948 it fills one-half. In both pictures it has become the central subject. Formerly deprived of the very style it inspired, it is now the single thing in the picture to which the leaf-light striping is emphatically applied. The palm in Still Life with Pomegranate is composed of hundreds of green stripes against light blue. The palm in Interior with Egyptian Curtain is composed of hundreds upon hundreds of stripes in black, green, yellow, white. On the wall inside the 1948 canvas Large Interior in Red hangs a black-and-white picture with a palm outside the window and another palm inside the room—palm fronds painted with a palm frond on a palm frond—the painter’s material, instrument, and subject.

I began here with the way beautiful things have a forward momentum, the way they incite the desire to bring new things into the world: infants, epics, sonnets, drawings, dances, laws, philosophic dialogues, theological tracts. But we soon found ourselves also turning backward, for the beautiful faces and songs that lift us forward onto new ground keep calling out to us as well, inciting us to rediscover and recover them in whatever new thing gets made. The very pliancy or elasticity of beauty—hurtling us forward and back, requiring us to break new ground, but obliging us also to bridge back not only to the ground we just left but to still earlier, even ancient, ground—is a model for the pliancy and lability of consciousness in education. Matisse believed he was painting the inner life of the mind; and it is this elasticity that we everywhere see in the leaf-light of his pictures, the pliancy and palmy reach of the capacious mind. Even when the claim on behalf of immortality is gone, many of the same qualities—plenitude, inclusion—are the outcome.

It sometimes seems that a special problem arises for beauty once the realm of the sacred is no longer believed in or aspired to. If a beautiful young girl (like Nausicaa), or a small bird, or a glass vase, or a poem, or a tree has the metaphysical in behind it, that realm verifies the weight and attention we confer on the girl, bird, vase, poem, tree. But if the metaphysical realm has vanished, one may feel bereft not only because of the giant deficit left by that vacant realm but because the girl, the bird, the vase, the book now seem unable in their solitude to justify or account for the weight of their own beauty. If each calls out for attention that has no destination beyond itself, each seems self-centered, too fragile to support the gravity of our immense regard.

But beautiful things, as Matisse shows, always carry greetings from other worlds within them. In surrendering to his leaf-light, one is carried to other shorelines as inevitably as Odysseus is carried back to Delos. What happens when there is no immortal realm behind the beautiful person or thing is just what happens when there is an immortal realm behind the beautiful person or thing: the perceiver is led to a more capacious regard for the world. The requirement for plenitude is built-in. The palm will always be found (whether one accidentally walks out onto a balcony, or follows at daybreak the flight path of an owl, or finds oneself washed up in front of Nausicaa or a redbud or Seated Woman with a Book) because the palm is itself the method of finding. The material world constrains us, often with great beneficence, to see each person and thing in its time and place, its historical context. But mental life doesn’t so constrain us. It is porous, open to the air and light, swings forward while swaying back, scatters its stripes in all directions, and delights to find itself beached beside something invented only that morning or instead standing beside an altar from three millennia ago.

This very plasticity, this elasticity, also makes beauty associate with error, for it brings one face-to-face with one’s own errors: momentarily stunned by beauty, the mind before long begins to create or to recall and, in doing so, soon discovers the limits of its own starting place, if there are limits to be found, or may instead—as is more often the case—uncover the limitlessness of the beautiful thing it beholds. Though I have mainly concentrated here on failures of plenitude and underattribution—mistakes that involve not seeing the beauty of something—the same outcomes can be arrived at by the path of over-attribution, as registered in the poems about error by Dickinson, Hopkins, Shakespeare. This genre of error, however, has the peculiarity that when the beautiful person or thing ceases to appear beautiful, it often incites the perceiver to repudiate, scorn, or even denounce the object as an invalid candidate or carrier of beauty. It is as though the person or thing had not merely been beautiful but had actually made a claim that it was beautiful, and further, a claim that it would be beautiful forever.9 But of course it is we—not the beautiful persons or things themselves (Maud Gonne, Mona Lisa, “Ode to a Nightingale,” Chartres, a columbine, a dove, a bank of sweet pea, a palm tree)—who make announcements and promises to one another about the enduring beauty of these beautiful things. If a beautiful palm tree one day ceases to be so, has it defaulted on a promise? Hopkins defends the tree:

No, the tropic tree

Has not a charter that its sap shall last

Into all seasons, though no Winter cast

The happy leafing.

The temptation to scorn the innocent object for ceasing to be beautiful might be called the temptation against plenitude; it puts at risk not the repudiated object but the capaciousness of the cognitive act.

Many human desires are coterminous with their object. A person desires a good meal and—as though by magic—the person’s desire for a good meal seems to end at just about the time the good meal ends. But our desire for beauty is likely to outlast its object because, as Kant once observed, unlike all other pleasures, the pleasure we take in beauty is inexhaustible. No matter how long beautiful things endure, they cannot out-endure our longing for them. If the beauty of an object lasts exactly as long as the life of the object—the way the blue chalice of a morning glory blossom spins open at dawn and collapses at noon—it will not be faulted for the disappearance of its beauty. Efforts may even be made to prolong our access to its beauty beyond its death, as when Aristotle, rather than turning away from a dying iris blossom, tracks the changing location of its deep colors, and Rilke, rather than turning away from the rose at the moment it breaks apart, describes the luxurious postures the flower adopts in casting down its petals.

But if the person or thing outlives its own beauty—as when a face believed ravishing for two years no longer seems so in the third, or a favorite vase one day ceases to delight, or a poem beloved in the decade when it is written becomes incomprehensible to those who read it later—then it is sometimes not just turned away from but turned upon, as though it has enacted a betrayal. But the work that beautiful persons and things accomplish is collectively accomplished, and different persons and things contribute to this work for different lengths of time, one enduring for three millennia and one enduring for only three seconds. A vase may catch your attention, you turn your head to look at it, you look at it still more carefully, and suddenly its beauty is gone. Was the beauty of the object false, or was the beauty real but brief? The three-second call to beauty can have produced the small flex of the mind, the constant moistening, that other objects—large, arcing, flexuous—will more enduringly require. We make a mistake, says Seamus Heaney, if, driving down a road between wind and water, overwhelmed by what we see, we assume we will see “it” better if we stop the car. It is there in the passage. When one goes on to find “better,” or “higher,” or “truer,” or “more enduring,” or “more widely agreed upon” forms of beauty, what happens to our regard for the less good, less high, less true, less enduring, less universal instances? Simone Weil says, “He who has gone farther, to the very beauty of the world itself, does not love them any less but much more deeply than before.”

I have tried to set forth the view here that beauty really is allied with truth. This is not to say that what is beautiful is also true. There certainly are objects in which “the beautiful” and “the true” do converge, such as the statement “1 = 1.” This may be why, though the vocabulary of beauty has been banished or driven underground in the humanities for the last two decades, it has been openly in play in those fields that aspire to have “truth” as their object—math, physics, astrophysics, chemistry, biochemistry—where every day in laboratories and seminar rooms participants speak of problems that are “nice,” theories that are “pretty,” solutions that are “beautiful,” approaches that are “elegant,” “simple.” The participants differ, though, on whether a theory’s being “pretty” is predictive of, or instead independent of, its being “true.”10

But the claim throughout these pages that beauty and truth are allied is not a claim that the two are identical. It is not that a poem or a painting or a palm tree or a person is “true,” but rather that it ignites the desire for truth by giving us, with an electric brightness shared by almost no other uninvited, freely arriving perceptual event, the experience of conviction and the experience, as well, of error. This liability to error, contestation, and plurality—for which “beauty” over the centuries has so often been belittled—has sometimes been cited as evidence of its falsehood and distance from “truth,” when it is instead the case that our very aspiration for truth is its legacy. It creates, without itself fulfilling, the aspiration for enduring certitude. It comes to us, with no work of our own; then leaves us prepared to undergo a giant labor.