Soon after the arrival of Henry VII’s troops in the city, London was struck with a deadly and hitherto unknown disease. Probably a viral infection, it became known as ‘the sweat’ and was feared not only because of the high mortality rate, with ‘scarcely one in a hundred’ of those who contracted the disease surviving, but also because its victims died quickly, generally within twenty-four hours. Whereas the plague was thought of as mostly afflicting the poor, because the well-to-do took evasive action and left built-up areas, the sweat struck both the prosperous and the poor.

Severe epidemics of both the sweat and plague occurred intermittently through the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. An epidemic in 1498 carried off perhaps 10,000 people in London, the sweat returned in 1508–09 and during a ‘great plague’ in 1513 the daily death toll reached as high as 300 to 400. In the summer of 1517 another outbreak of the sweat was swiftly followed by a plague epidemic. Such eruptions prompted the introduction of measures designed to prevent the spread of diseases during an epidemic and to provide for the sick during their illness. Although the first such steps were taken in 1518, a codification of the orders for London was not issued until 1583. That was twenty years after the worst plague outbreak in the capital during the Tudor era in 1563, when 23,660 died, 85 per cent of them from plague, or roughly one-fifth of the population.

Despite the death toll during such outbreaks, and the high mortality levels during non-epidemic years, London’s population continued to grow. Having taken two centuries to reach its pre-Black Death level, it then surged ahead relentlessly during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. The number of inhabitants rose from roughly 80,000 in 1550 to 200,000 in 1600 and perhaps 260,000 by 1625. That growth came to be a major concern to the government. It feared the threat to public health, for polluted air and a foul environment were thought to be among the causes of disease, exacerbated by overcrowding in such a large city. Another concern was the rising number of poor people, which placed a strain on the system of poor relief and raised the spectre of social instability and unrest. The problems of the ever-expanding suburbs with ‘filthy cottages’, overcrowded tenements and rubbish dumps could not be ignored. The population increase had led to rapid and sometimes shoddy building, the adaptation of outbuildings to provide living space, the infilling of spaces within the city and the subdivision of houses. To curb the city’s growth, a proclamation was issued in 1580 which prohibited new building and ordered that a house should be occupied by only one family, but this and subsequent orders were futile. London’s growth was inexorable.

19. The coronation procession of Anne Boleyn, Henry VIII’s second wife, in 1533, shown passing Westminster Abbey. From a drawing by David Roberts. (Jonathan Reeve, JR968b42p404 15001600)

Families, apprentices and journeymen lived cheek-by-jowl in overcrowded accommodation, where privacy was a rare commodity, and warmth and security were perhaps greater priorities. Beds were placed not only in bedchambers but in any other available room or space, rooms were interconnected so that a bedchamber often provided a passageway to a room beyond, and children and servants were likely to share a bed with the husband or wife when there was an opportunity to do so. Privacy in bed could be obtained only behind the bed-curtains, for those who could afford them. As the winters grew distinctly colder towards the end of the century, warmth would have overridden other considerations when sleeping arrangements were made.

20. Henry VII’s chapel in Westminster Abbey was completed after his death in 1509 and contains his tomb, with his queen, Elizabeth of York, and other royal tombs added later. This painting is by John Fulleylove. (Stephen Porter)

21. The livery companies were a major force in London’s economy and administration. This painting, after Hans Holbein, depicts Henry VIII’s grant of a charter to the Barber-Surgeons’ Company in 1540. (Stephen Porter)

In contrast to the scruffy and disreputable suburbs, the centre of the city contained timber-built houses of three and four storeys, roofed with tiles, but the frontages lacked uniformity, which came to be perceived as a shortcoming as tastes changed. A proclamation issued in 1605 attempted to improve the city’s appearance by ordering that the fronts of houses should be of brick or stone and that ‘the forefront thereof in every respect shall be made of that uniforme order and forme, as shall be prescribed unto them for that Streete’. That could be applied only to new or rebuilt houses, and so this change envisaged would take time to achieve. In any case, enforcement of all such environmental policies was hindered by the refusal of the City’s government to expand its boundaries, and so while the area governed by the mayor and aldermen was closely regulated, the built-up area beyond was administered by the Middlesex and Surrey justices of the peace, with less authority and fewer resources in larger parishes. In the mid-sixteenth century 75 per cent of Londoners lived in the City, but the proportion fell as the population increased, and by 1700 it was only 25 per cent.

The authorities did not face a famine crisis when harvests were deficient and only occasionally were they troubled by protests against high prices, for population growth did not produce food shortages. Supplies kept pace with the city’s expansion and were drawn from a wide area of England, and increasingly from Wales and Scotland, too. Market gardens were developed around the city from the late sixteenth century, providing its fruit and vegetables, and by 1617 they were said to employ ‘thowsands of poore people’. The markets were regulated and the aldermen intervened when necessary to limit price increases. Water supplies were augmented, most notably with the opening of the New River in 1613, which brought water from Hertfordshire to Clerkenwell.

London’s growth was fuelled largely by those attracted to the city from the provinces, for economic reasons. The livery companies had a near monopoly on the control of skilled labour, but they came under scrutiny in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, and had to present their regulations to the City for inspection and modification. Moreover, Parliament acted in the 1530s to remove restrictive practices by the companies, by fixing the fees payable by apprentices and prohibiting surcharges on their entrance fees, and so stopping the practice of limiting access to a trade by charging high fees. It also banned the custom of imposing an oath on men at the end of their apprenticeships by which they undertook never to set up shops, and so be competitors for the established figures in the trade. Those measures removed a potential restriction on the labour supply and the size of the livery companies and so London’s economy was able to respond when there was a boom during the mid-century, especially in the textile trades.

22. The gatehouse of the inner precinct of the Priory of St John of Jerusalem in Clerkenwell, founded around 1144, was built in 1504. (Stephen Porter)

Others were attracted to London from the Continent, and about 3,000 ‘strangers’ lived in the city in 1500. Although their communities were small, they attracted resentment from time to time. There were anti-Italian flare-ups in 1456 and 1457, attacks on the Steelyard in 1462 and 1494, and a more serious riot in 1517, directed against the Flemish community, which came to be known as Evil May Day. Yet no similar anti-immigrant riot occurred thereafter, even though anxiety about the numbers of strangers prompted the city authorities and the government to organise enumerations. At a count taken in 1573 the city contained 7,143 strangers, which was a small proportion of the whole population. The Dutch and Flemish community was settled chiefly east of the Tower and in Southwark, and other incomers came from France and Germany. During the second half of the sixteenth century religious refugees seeking asylum from persecution in the Low Countries and France came to form a significant proportion of the incomers. But London’s prosperous and expanding economy provided a strong economic motive, with roughly a third of those recorded in 1573 stating ‘that their coming hither was onlie to seeke woorke for their livinge’.

The city contained a range of manufacturing and service trades, skilled and semi-skilled workers, and wholesalers and retailers, who were described by the historian of London John Stow in 1598 as ‘mercers, vintners, haberdashers, ironmongers, milliners, and all such as sell wares growing or made beyond the seas’. The merchants met in the open in Lombard Street until the completion of the Royal Exchange, in 1568, provided a place for them to trade, gather news and exchange opinions.

Overseas trade was expanding, along both the long-standing routes with northern Europe and Iberia and those to the developing markets in the Americas, the Indian Ocean and the East Indies. Between 1555 and 1609 trading companies were formed for the commerce with the new regions: the Muscovy Company, the Eastland Company (for trade with Scandinavia and the Baltic), the Turkey Company, the Venice Company (the Turkey and Venice companies became the Levant Company in 1592), the East India Company and the Virginia Company. The Barbary Company was established in 1585 for trade with Morocco, but was dissolved twelve years later. The range of goods imported steadily widened, with pepper, currants, spices, silk, cotton, indigo, calico, dyes and sugar being brought in. Wine imports rose fivefold between 1563 and 1620 and as tobacco increased in popularity it became one of the more valuable imports. By the end of the sixteenth century London handled roughly 80 per cent of England’s imports and exports.

23. The Great Hall in the Charterhouse, a courtyard house built by Sir Edward North in 1546, incorporating parts of the Carthusian priory established on the site in 1371 and closed in 1538. (Stephen Porter)

Among the forces driving the city’s economy was the presence of the royal court at Westminster Palace, until a fire there in 1512, and from 1529 at Whitehall Palace, which became the principal royal residence. The sittings of Parliament were more frequent from the reign of Henry VIII and continued to be held in Westminster, as did those of the courts of law. The aristocracy and the country gentry began to bring their families with them on their visits to London, for the meetings of Parliament or for social and business reasons, and to stay longer, producing a growing market for suitable accommodation and fashionable luxury goods, and business for the steadily developing professions.

In the 1520s Henry VIII’s concerns over his lack of a male heir led to his seeking an annulment of his marriage to Katherine of Aragon. The Pope was unable to oblige and Henry’s solution was to break from the papacy and make himself head of the English Church. Having achieved that, the king then expelled the monastic orders, dissolved the religious houses and their hospitals, and re-appropriated their lands and buildings. Most monks acquiesced, but members of the Carthusian order did not. The prior of the London Charterhouse, John Houghton, was executed in May 1535, together with the priors of Beauvale and Axholme. By 1540 ten monks and six lay brothers of the London Charterhouse had been executed or had died in prison, but no other order followed their example. The monastic property that was then disposed of included roughly one-third of properties within the city walls. Their sale released those houses onto the market, while the sites of the monasteries themselves were generally converted to grand houses by the wealthy. Among the exceptions was the Greyfriars in Newgate Street, which was given to the corporation. The grant of the Greyfriars was confirmed by Edward VI when he established Christ’s Hospital there, for ‘poor fatherless children’. Also presented to the city were St Thomas’s Hospital, Bridewell Palace, which came to be used as a prison and workhouse, and a school for orphans and young criminals, and Bethlehem Hospital, which from 1377 had taken care of the insane and was continued as a mental asylum, generally known as Bedlam. But the chapel of Thomas à Becket on the bridge was demolished in 1553. Coincidentally, during the 1530s the ecclesiastical palaces which lined the Strand were acquired by members of the aristocracy and leading courtiers.

24. The coronation procession of Edward VI from the Tower to Westminster in 1547 is shown processing along Cheapside. This copy was made by Samuel Hieronymus Grimm (1733–94). (The Society of Antiquaries of London)

25. Detail from above illustration highlighting people relaxing on Tower Hill, as the procession streams out of the Tower. (The Society of Antiquaries of London)

26. Tower Hill was the site of executions of prominent people, which attracted large crowds. This nineteenth-century illustration shows the execution of Lord Guildford Dudley in 1554. (Stephen Porter)

The redistribution of property could not be reversed during the reign of Mary Tudor (1553–58), when England returned to the Catholic faith and Protestants were persecuted. Between 1555 and Mary’s death in November 1558, 283 people were burnt, seventy-eight of them in London, of whom fifty-six were executed in Smithfield. Although only roughly a fifth of the Protestant martyrs were burnt there, ‘the fires of Smithfield’ came to symbolise those burnt to death for their faith during Mary’s reign. Mary’s sister Elizabeth succeeded her and reversed these religious policies; Protestantism was restored and became firmly established during her long reign, until her death in 1603.

The religious debates extended to the level of charitable giving, with Catholic writers claiming that it had been adversely affected by the Reformation. In fact, the pace of donations increased, with contributions and bequests to support the poor and elderly. They included funeral doles, collections for specific charitable needs and formal giving through the establishment of charities, such as those for the distribution of bread or the founding of schools and almshouses. Endowments were received from Londoners as well as those who had left the capital and become country gentry, who continued to establish and support charities in the city where they had made their fortunes. The most spectacular charity, for its scale and setting, was the almshouse for eighty men and school for forty boys established by Thomas Sutton in 1611 in the mansion built on the site of the Carthusian priory. Poor relief was also administered through the parishes, with a rate levied from householders for the purpose, a practice which was adopted by the government as a policy in 1572. The Poor Law arrangements were confirmed by legislation in 1598 and 1601.

Yet not everyone was happy with the level of giving and Stow complained that the citizens were now spending their money for show and pleasure. His comment referred to a growing enjoyment of prosperity and leisure. The citizens turned out in large numbers to watch the annual procession celebrating the inauguration of a new mayor. In the fifteenth century the mayors had taken a barge to Westminster to swear their oath of office, and during the sixteenth century that developed into a numerous and colourful armada of boats, with the mayor returning to the Guildhall in a procession that contained exotic animals, floats and a variety of entertainers. Another popular annual event was Bartholomew Fair in Smithfield, which lasted for three days in August. It combined a range of entertainments, such as puppeteers, conjurers, actors, balladeers, wrestlers, tightrope-walkers and fire-eaters, with trading, especially in cloth, leather, pewter, livestock, and butter and cheese. It was followed in early September by Southwark Fair, also a three-day event, which had been held from at least as early as the 1440s.

More regular entertainments included archery, dancing, music, bell-ringing and football, and watching cockfighting, animal-baiting and plays. Londoners most often went to Bankside, on the south side of the river, for their recreation. Until the mid-sixteenth century the district attracted attention chiefly because of its brothels, but it then became increasingly popular for its bull- and bear-baiting, in two arenas, and then its theatres. The earliest purpose-built playhouse was erected in Whitechapel in 1567 and others followed, in Shoreditch, Newington Butts, Clerkenwell and Bankside, and later indoor theatres at Blackfriars and in Drury Lane. Shakespeare was associated through his company, the Chamberlain’s Men (the King’s Men following James I’s accession in 1603), with the Globe, which was erected in Shoreditch in 1595 and was dismantled and reassembled on Bankside, where it reopened in 1599. Plays ran for only a few performances and so writers needed to produce a steady flow of new material. The audiences were drawn from a wide social range and probably numbered 21,000 per week by the early seventeenth century, when three playhouses and two hall theatres were open.

27. The crowded buildings of Tudor London are depicted around 1585, showing the City, between the Strand and St Katherine’s, with Southwark in the foreground. (Stephen Porter)

28. The court contributed significantly to London’s economy. Here Queen Elizabeth is dancing with the Earl of Leicester, her favourite; the artist is unknown. (Stephen Porter)

29. At a feast at Bermondsey around 1570 musicians accompany the dancers, food is being prepared in the building and tables are set for the meal. The painting by Joris Hoefnagel was copied by Samuel Hieronymus Grimm. (The Society of Antiquaries of London)

The theatres also attracted criticism, however. The Puritans, who were increasingly prominent in the city, found them repugnant on moral grounds, and both national and civic governments saw them as a risk to public health. Theatres were closed during plague epidemics, which occurred in 1592–93, the worst since 1563; in 1603, in the early months of James I’s reign; and in 1625, soon after his son Charles had come to the throne. The outbreaks in 1603 and 1625 each killed roughly one-fifth of London’s population, but in both cases it returned to its pre-plague level within two years, because of the numbers drawn in to replace those who had died. Neither such devastating epidemics nor government policy on building checked the city’s growth, which emphasised its economic power and unassailable position as the country’s dominant city.

30. The interior of the Swan Theatre on Bankside, built in 1595 and sketched by Johannes de Witt in the following year. This is a copy of his sketch. (Stephen Porter)

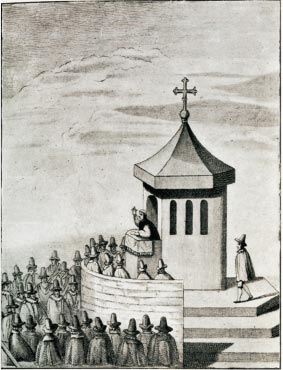

31. Paul’s Cross was an open-air pulpit close to St Paul’s Cathedral; sermons there attracted large congregations. The cross was demolished in 1643. (Stephen Porter)

32. Claes Visscher’s view of 1616 shows London Bridge, the Pool of London, where ships loaded and unloaded their cargoes, and the densely packed buildings between the bridge and the Tower. (Stephen Porter)