Chapter 4

Finding Your Motivation

In This Chapter

Understanding motivation and how it links to confidence

Understanding motivation and how it links to confidence

Applying motivation theories to increase your confidence

Applying motivation theories to increase your confidence

Your personal motivation is the force that gets you out of bed in the morning and provides you with energy for the work of the day. This motivation is what keeps you pressing forward in the face of difficulties. Have you ever wondered why you seem to be bursting with it some days, and other times it seems to desert you entirely?

Understanding how motivation works so that you can access your natural motivation to help manage the life you want with more confidence and ease is what this chapter is about. It gives you the insight you need to keep moving forward despite the challenges you face.

The most important thing you can take from this chapter is that you don’t have to put up with feeling weak and unmotivated, lacking in confidence. If you deal intelligently with blocks in your natural energy source, you can restore your energy, achieve more with less effort, and feel more at ease with life, more satisfied with yourself, and more confident and powerful in the world.

Driving Forward in Your Life

The more motivated you feel, the more inclined you are to push yourself through the things that are holding you back, (which is how we define confidence in Chapter 1). If you can increase your motivation, you automatically increase your confidence. In the next sections, we look at Abraham Maslow’s influential hierarchy of needs to help you gain insight into what motivates you and everyone you come into contact with.

Rising through Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

One of the founders of the human potential movement, Abraham Maslow, is best known for his work on human motivation. He was fascinated by what makes some people able to face huge challenges in life, and especially what makes them refuse to give up despite incredible odds. He developed the model for which he is best known – his hierarchy of needs, shown in Figure 4-1 – to explain the forces that motivate people.

Figure 4-1: Looking at Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

Maslow saw men and women being constantly drawn on through life by the irresistible pull of unsatisfied needs. He grouped human needs into a hierarchy, which everyone shares and needs to satisfy from the bottom up. This model is widely taught in management development courses, but his work goes far beyond the workplace to the very heart of our humanity.

Maslow believed that you must first satisfy your basic physiological needs for air, water, food, sleep, and so on before any other desires will surface. As a member of modern society, these basic needs are largely taken care of for you, but if you’ve ever been short of breath under water you know and understand how this first-tier, physiological need dominates everything else until satisfied.

But when your physiological needs are met, you automatically shift up to the next level in the hierarchy to your broader need for safety – and that now drives you. Again, modern society tends to provide safe environments, but whenever you do feel threatened, you experience an automatic anxiety response and cannot think of much else until the situation is resolved and you feel safe again.

At the next level, you have to make more personal interventions to ensure that your needs are satisfied within the framework that society provides for you. Your needs for love and connection show up here; things you don’t automatically get all the time. If your needs at this level are unsatisfied, and you feel isolated or lonely, you find it almost impossible to meet your higher-level needs in any meaningful way.

The next level is where your needs for self-esteem and recognition kick in. These needs may never have been an issue for you as you struggled to join your group, but now they can become dominant. It is no longer enough simply to belong; now you must have some power and status in the group too – drive a bigger car, become captain of the golf club perhaps, or chair of the school parent–teacher association. This level is where most established adults reside most of the time today.

But thankfully, the endless striving does end, and with all your needs taken care of, you eventually arrive at the top of Maslow’s hierarchy as a fully developed human being. At the exotically named self-actualisation stage, your major motivation becomes living and expressing what is truly most important to you in life. Often, this stage is where you get to give something back to the world that has supported you so royally in your journey through life so far.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs helps to explain so much of the variability in human behaviour. Different human beings operate at different levels, and are driven by different needs at any given time. Your motivation level may be different on Monday from on Friday with the weekend looming. And of course, you may feel different at work from the way you feel at home. The more you understand what drives you, the better able you are to find the confidence to achieve the things you want in life.

Greeting the world with grace

Maslow is often associated with motivation at work, but his insights apply equally in social situations where you can use them to help put yourself at ease.

When you find yourself in a new social group – meeting new people at a party or function, for example – you can expect to feel anxious because at this moment you’re at Maslow’s third level, needing to be accepted into this new group.

You can still meet and greet people confidently, of course, but you may not feel like it right now. When you’re in this situation, the first thing to do is to accept your mild anxiety about it. Nothing is wrong with feeling nervous (in case the voice inside your head starts accusing you of being a wimp), but you don’t need to let these feelings prevent you from making new friends.

Remember, everyone in the room fits into Maslow’s hierarchy and is therefore feeling needy at some level. The people you’re meeting who are not new to the group are operating at the second and third levels: some are still anxious for acceptance, just as you are (and these people are just as keen to be accepted by you as you are by them); some are motivated by their need for social esteem and need your respect.

Depending on the kind of party you’re at, you can expect to witness needy behaviours at all levels from hunger and thirst, through sex, connection, companionship, to a close approximation of self-actualisation on the dance floor. Don’t judge your fellow partygoers too harshly. In fact, give everyone at the party a break, including you. Enjoy the spectacle!

Take on board these new factors in an otherwise ordinary and potentially dull social dynamic by paying attention to the curious and interesting display of need-motivated behaviours going on around you.

If you’re curious about the people in the group and really take an interest in what’s happening, you come across to others as attentive and a great conversationalist. This situation is more fun for you, and more fun for the people you meet. Pretty soon, everyone will want you at their parties.

Bringing this more curious and attentive version of yourself into social situations lessens your anxiety, because you focus on the impression other people are making on you rather than the one you’re making on them. You always appear charming to those you meet if you give them the gift of your rapt attention. People aren’t used to this attention and they’ll love you for it.

Bringing this more curious and attentive version of yourself into social situations lessens your anxiety, because you focus on the impression other people are making on you rather than the one you’re making on them. You always appear charming to those you meet if you give them the gift of your rapt attention. People aren’t used to this attention and they’ll love you for it.

Taking Charge at Work

Your ability to take action (our definition of confidence) is critical to your performance in the world, and in work this ability is usually just as important to the performance of your boss and co-workers too. For this reason, motivation for action has become the focus of a lot of social science research over the last 60 years, and in this section, we show you how to use some of this research for your personal benefit at work.

Looking at usable theory

Maslow’s theory about human needs is universal, applying to everyone in all situations. Other important theorists, such as Frederick Herzberg and William McGregor, have focused on your motivation to achieve results at work, which is important to you and to your employer. In this section, you find out how to take more control of and increase your motivation at work. You also find a self-test to help you to measure your progress.

Searching for satisfaction with Herzberg

Frederick Herzberg is a motivation guru frequently studied on management development courses (which means that your senior colleagues should have heard about him). His elegant theory reveals the factors that energise you at work, helping you to behave confidently and get things done, and those that take your natural energy away. He separates out those forces that motivate people, called motivators, from those that sap motivation, the dissatisfiers. He discovered that these forces operate in a surprising, seemingly illogical way.

Take pay as a universal example. You may think that the money you’re paid provides you with motivation, and most employers act as though money is the main motivation, but it simply isn’t true in the long term according to Herzberg. Pay is a dissatisfier and not a motivator. If you aren’t being paid the rate for the job, your poor pay rate can certainly make you feel dissatisfied, but surprisingly, of itself being paid over the odds doesn’t motivate you any further than being paid a fair rate (although it may bring other factors into play, such as recognition and team status).

Recognition, on the other hand, is a motivator. For this reason, a good job title, a sincere word of thanks from the boss, or a mention in the in-house journal for a job well done can be so motivating.

Table 4-1 contains a list of some of the main motivators and dissatisfiers that Herzberg identified. The dissatisfiers on the left have to be carefully managed or they can create serious dissatisfaction for you, but of themselves they cannot motivate you. The factors on the right are the motivators and give you the drive you need to feel confident and do your best work, but they don’t come into play until the dissatisfiers have first been neutralised.

Notice that the factors in the left column are external to the work itself and are largely imposed on you from outside. The motivators in the satisfaction column are much more personal, in that they tend to be more closely tied to the job you do. They’re also more psychological, in that you’ve personal discretion over how much of them you feel. For this reason, you can use them to maintain your confidence levels.

If this insight starts to resonate powerfully for you, you may want to read up a bit more on Herzberg’s motivation-hygiene theory before having a discussion about it with your boss. The dissatisfiers present in your work may be easy for your boss to neutralise, leaving you unencumbered psychologically to bring your motivation into play.

Unless you feel the presence of the motivators to a degree that has significance for you, you won’t be motivated or satisfied at work no matter what else the company does for you.

Unless you feel the presence of the motivators to a degree that has significance for you, you won’t be motivated or satisfied at work no matter what else the company does for you.

Mapping McGregor’s Theory X and Theory Y

Douglas McGregor’s work is less well known to general managers, which is a shame as it focuses closely on management style (one of Herzberg’s key dissatisfiers). McGregor brought out the effects of reactionary and over-zealous management practices and policies in his two models: Theory X and Theory Y.

Theory X assumes that, as a worker, you’ve an inbuilt dislike of working and shirk as much as you can get away with. Therefore, you need to be controlled to ensure that you put in the effort needed, and you need to be told exactly what to do and how to do it. This attitude can be damaging to your natural motivation, your job satisfaction, and eventually your self-belief and confidence. Studies suggest that if your boss treats you this way, you may begin to behave as if it were true. (If this situation is happening to you, use the feedback model in Chapter 15 to make this point to your supervisor or departmental representative.)

Theory Y takes the opposite view. It assumes that working is important to you, and as natural to you as the other parts of your life. If your work is satisfying, it becomes a source of drive and fulfilment, increasing your personal confidence. You become committed to it and you require little in the way of supervision.

You perform better and are more productive if you’re allowed to manage your own workload, output, and so on, because you know so much better than anyone else how to get the best out of yourself. In these circumstances, your supervisor becomes a colleague you can consult when you need a second opinion and who can liaise with senior management to enable you to do the best job possible.

How do these two models compare with your own job situation? The chances are that your own supervision has elements of both Theory X and Theory Y. As ever, the onus is on you to take more control of an element of your life. When you have knowledge, you’ve the opportunity to put it confidently to use.

Taking action may require all the confidence you can muster, and in this case it repays you doubly by getting you what you want and by helping to build your confidence for the future.

Taking action may require all the confidence you can muster, and in this case it repays you doubly by getting you what you want and by helping to build your confidence for the future.

The challenge you face is not so much individuals and their personal attitudes but organisation structures and the way jobs are organised. If you supervise a team, or even just work in a team, following Theory Y gives you a far better chance of getting the results you need. Educate your colleagues where you can and help to bring your teams into the 21st century.

Putting theory to the test

In this section, you see how to use the theoretical insights from the preceding sections to build your confidence as you engage with the world. And because most motivation theory is based on the workplace, you start there.

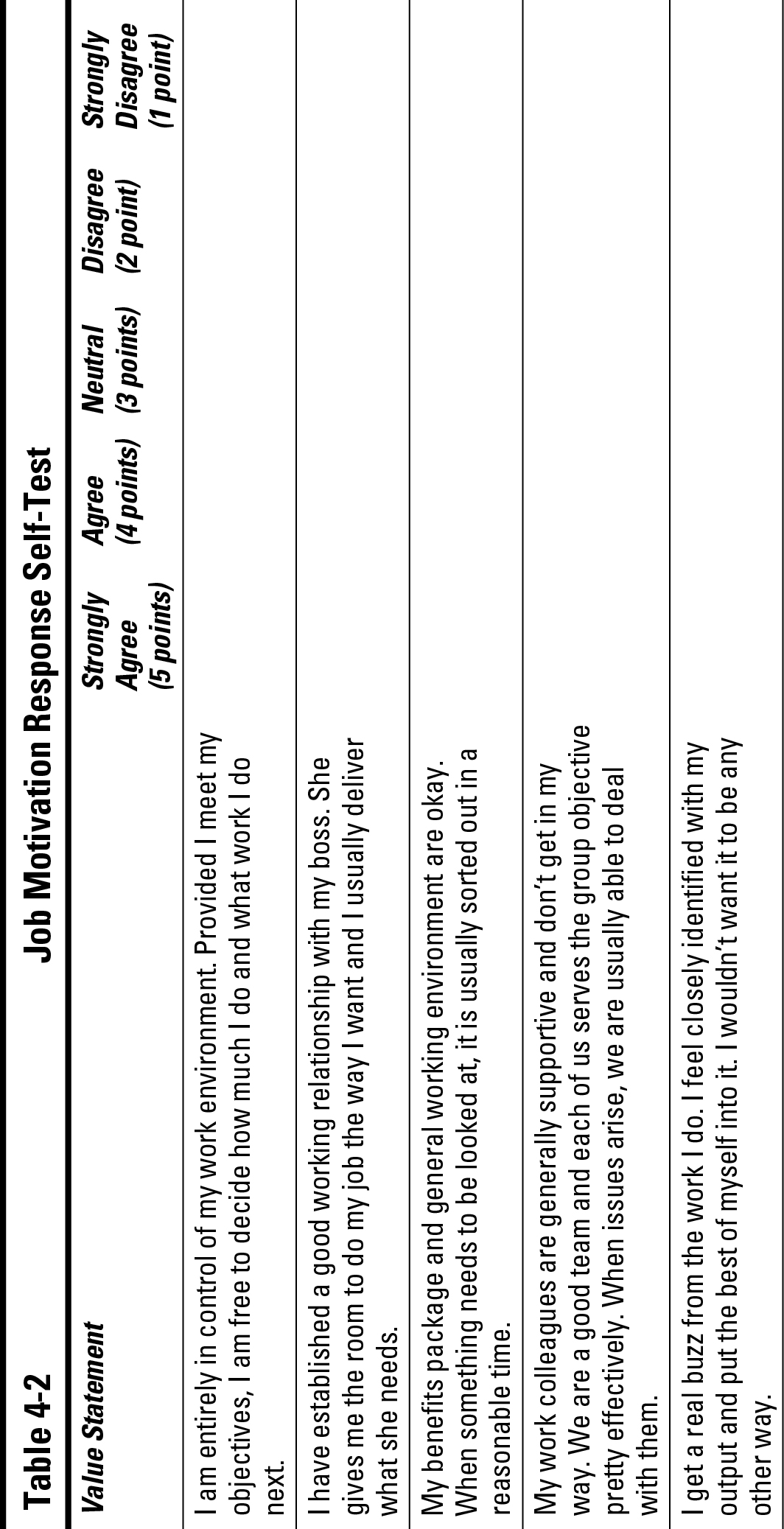

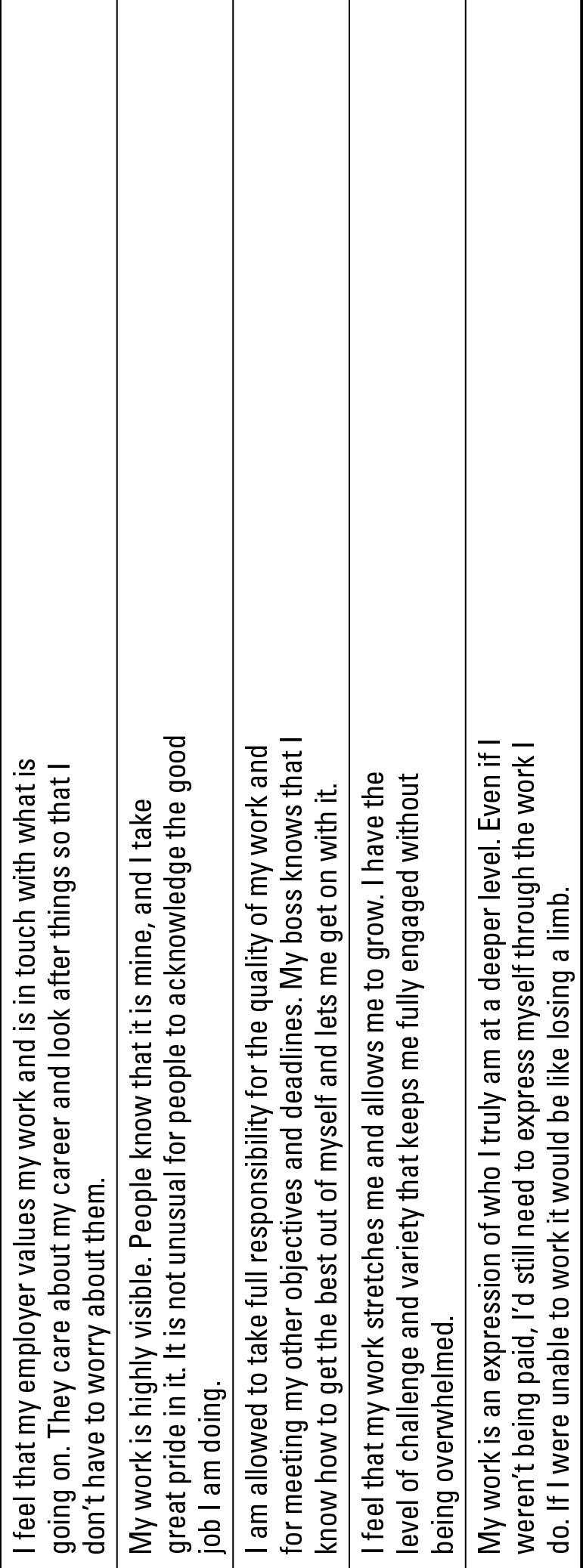

Whether you work for yourself or for someone else, you have to meet your motivational needs. Table 4-2 provides a self-test you can take in five minutes that measures your motivation response at work. If you work alone, modify the questions as necessary to suit your circumstances. Give yourself up to five points for each question – all five if you strongly agree, down to one if you strongly disagree.

Whether you work for yourself or for someone else, you have to meet your motivational needs. Table 4-2 provides a self-test you can take in five minutes that measures your motivation response at work. If you work alone, modify the questions as necessary to suit your circumstances. Give yourself up to five points for each question – all five if you strongly agree, down to one if you strongly disagree.

Use these guidelines to evaluate your score:

40–50: Congratulations, you may have found your life’s work. You’re working in a job that gives you most of what you need not only for motivation but for your growth and fulfilment too.

40–50: Congratulations, you may have found your life’s work. You’re working in a job that gives you most of what you need not only for motivation but for your growth and fulfilment too.

30–40: This score is good. You should be able to see the areas that are pulling you down and you can develop some goals for changing them. Use the SMART goal-setting technique in Chapter 3 to help create the changes you need.

30–40: This score is good. You should be able to see the areas that are pulling you down and you can develop some goals for changing them. Use the SMART goal-setting technique in Chapter 3 to help create the changes you need.

10–30: You may already know that this score isn’t so good. You probably need to take more personal responsibility for your motivation at work, which can include changing your job or organization. Take a look at the techniques in Chapter 15 to help you take more control of your work.

10–30: You may already know that this score isn’t so good. You probably need to take more personal responsibility for your motivation at work, which can include changing your job or organization. Take a look at the techniques in Chapter 15 to help you take more control of your work.

Recognising the importance of achievement

Achieving results at work isn’t just a matter of pleasing your boss and earning a bonus. It forms an important contribution to your personal sense of significance and wellbeing as you move confidently up the hierarchy of needs (see Figure 4-1) and a sense of achievement is top of the list of Herzberg’s motivators (refer to Table 4-1).

As you progress at work, you need to think more about what constitutes achievement for you. Consider what you want out of your life and work, and then, without working any harder, you should be able to secure more of it both for yourself and your employer. Doing so increases your sense of fulfilment and satisfaction and provides you with more motivational energy for more confident achievement.

Your relationship to your work is an influential part of your relationship to the world and all it contains. To achieve the most confident and powerful version of yourself, you need to understand and manage your value and contribution through your work in the world.

Your relationship to your work is an influential part of your relationship to the world and all it contains. To achieve the most confident and powerful version of yourself, you need to understand and manage your value and contribution through your work in the world.

Going for the next promotion

Like most people, when a promotion opportunity comes up, you may want to seize the chance to get it immediately (not least because if you don’t get it someone else will). But think carefully about what the promotion may mean for you before you go for it.

A not-uncommon situation is for a successful and happy worker to win a promotion only to become a less successful and far less happy supervisor or manager. When this kind of promotion happens, the person can remain stuck in their new role where their poor performance rules out any further advancement and the organisational hierarchy prevents them from returning to where they were good and happy.

If you know anyone who has been caught in this way, you understand that this kind of problem is hardly a recipe for organisational achievement – much less for personal confidence and fulfilment. Armed with knowledge of this chapter, no reason remains why it should happen to you.

Before you accept any new role, ask yourself:

Before you accept any new role, ask yourself:

How did things play out for the previous person who held this job? Perhaps they went on to even higher things, or perhaps they were stuck in the role for a long time and didn’t appear too happy in it.

How did things play out for the previous person who held this job? Perhaps they went on to even higher things, or perhaps they were stuck in the role for a long time and didn’t appear too happy in it.

What is likely to happen to you if you remain a while longer in your current role? Is there an even better promotion coming up soon? Would your refusal to take on the promotion offered send a bad or a good signal to your management?

What is likely to happen to you if you remain a while longer in your current role? Is there an even better promotion coming up soon? Would your refusal to take on the promotion offered send a bad or a good signal to your management?

How can you use the current situation to create the job you want? Would it be possible to change the new job into something that suits you better, retaining, say, some of your current responsibility? Or perhaps it would be possible to split up the new role and take only some aspects of it into your current role?

How can you use the current situation to create the job you want? Would it be possible to change the new job into something that suits you better, retaining, say, some of your current responsibility? Or perhaps it would be possible to split up the new role and take only some aspects of it into your current role?

How can you use the change on offer to let your colleagues and superiors know that you’re thinking deeply about the work you do and are not just in it for the next pay cheque? In the longer-term, this may be the most valuable aspect of the entire situation.

How can you use the change on offer to let your colleagues and superiors know that you’re thinking deeply about the work you do and are not just in it for the next pay cheque? In the longer-term, this may be the most valuable aspect of the entire situation.

Now, when the opportunity for promotion comes up, you’ve a richer way of evaluating why you’re interested in the new role, what it can bring to you other than money and what it can take away. And if you decide to go for it, you bring so much more to the table; acting confidently and making a good impression on your colleagues and leaving you with a big win whether or not you get the role.