Figure 10.1 A page from a version of Gorgias produced in AD 895. Wikipedia.

In Gorgias, Socrates takes on the master rhetorician who boasts of his ability to convince others of whatever point of view he may be employed to promote irrespective of its effect or its merits.1 For Plato, the result is mere trickery, a technique but not a technê whose goal is (or should be) real and thus actionable, shared knowledge about the world and our place in it. The rhetorician, while not mendacious, is nonetheless dangerous to the common weal because, as Plato puts it, “Nothing is worse for a human being than false belief,” and by his own admission, Gorgias is as happy arguing logical but ultimately insupportable falsities as he would be those that are deeply held, firmly supported, and socially beneficial. The result, Plato concludes, perverts justice and damages the community at large through the promotion of half-truths that are ultimately false truths.

Plato thus bequeathed to Western thought a clear distinction between hard-won insight and mere stratagems of persuasion that masquerade as knowledge. Taken as a whole, the dialogues present a carefully planned argument for a kind of knowing in service of a kind of being in the world with others. From Plato comes the moral definition of truth as something greater than the individual argument. It is instead a presupposition, to return to the language introduced in chapter 1, that by his definition first serves the community at large rather than an individual or single group. It is not that the rhetorician lies but that he does not tell a truth whose ultimate aim is social. The charge against Gorgias is not sophistry but, worse, bad citizenry where an informed citizenry is a moral good for which we all should strive.

Figure 10.1 A page from a version of Gorgias produced in AD 895. Wikipedia.

A second lesson of the dialogue is that truths are neither immutable nor self-evident but manufactured. Moreover, they have social consequences as we attempt to act ethically and honorably on their basis. Plato created, in effect, a consequential standard for the evaluation of arguments based not simply on (he said, she said) facticity but on their effect on society. When truths seem to conflict, when suppositions differ, then they must be evaluated by a communal, rather than an imperial (Singer’s objective observer) or idiosyncratic (“It’s true because I say it is”), yardstick. There is nothing virtuous about the rhetorician; the real virtue is society’s indulgence of his trade.

Mapping and statistics are techniques that, like the rhetorician’s persuasive speech, can be used to advance almost any argument, any proposition. Daily journalists similarly have no fixed subject; few have a specific expertise beyond the ability to present in relatively clear language another person’s point of view. It’s been that way for a long time, and the rationale is that reporters who are not experts may more faithfully broadcast another’s argument because they are not particularly informed. They are thus assumed to report without preconception or personal bias. Whether the reported statement is ethical or merely rhetorical is the speaker’s responsibility, not the reporter’s.2

Like the rhetorician, reporters are a persuasive lot whose task in theory is to promote only the smallest of truths (he said, she said). But there are a thousand ways in which any single story can be shaped. Young reporters learn them quickly (I certainly did) and learn, too, how to be persuasive. There is nothing wrong with that. Plato’s dialogues were themselves masterpieces of rhetorical construction. But in them he advances as a moral bedrock “human thriving,” and thus a socially grounded orientation, as the difference between his arguments and the self-promoting posture of those like Gorgias whose pride is grounded in ethical and moral vacuity. For today’s journalists, that perspective is, if not foreign, then rarely argued and more rarely advanced.

In the last of his dialogues, The Laws, Plato insisted that disconnected information is meaningless when severed from a setting in which people work together to achieve broadly desired social ends. The problem with the literature reviewed in chapter 2 was that most writers tried and failed to find a distinct morality and subsequent ethic unique to cartography, geography, graphic arts, journalism, or statistics. The authors assumed their own uniqueness, their own solitudes, taking Peter Singer’s objective world of disconnected, disinterested realities as real.

But as the examples of the past chapters demonstrate, any attempt to build an ethic in which independent, Olympian objectivity is the measure of success inevitably fails. “The truth of any statement, scientific or otherwise, which ultimately must rely on some anchoring, in order to avoid being completely arbitrary, is undecidable.”3 Data can’t serve as the sole anchor of our ethical judgments, a thing outside us, because data are not independent. Data do not speak. Their voice is not real but apparent, like that of a ventriloquist’s dummy. From the idea that sparks data’s collection to the approved methodologies that guide their organization, data are an artifact of our ideas, the propellant of the propositions we seek to enact. Data do not speak through us; we speak through them. In charting, graphing, mapping, and writing, we define and refine a dataset’s selective message. And so not simply as authors, cartographers, demographers, geographers, reporters, and statisticians, but more importantly as citizens, we are faced with a choice. We can be like Gorgias, arguing or at least analyzing whatever we are told to support or analyze. Or, like Plato, we can begin from the perspective of the shared moral good, one we then seek to define, refine, and defend as citizens through our work.

“We should strive for a kind of moral geometry with all the rigor which this term connotes,” John Rawls wrote in his Theory of Justice.4 That geometry is inherent in the structure of the map is why maps serve so well as an evidentiary medium in this discourse. “They link the territory to what comes with it—which is to say all of the desires, needs, and aspirations humans bring to them.”5 It is those aspirations—ethical, moral, practical, professional, and scientific—that they express.

The Rawlsian geometry of a map’s moral underpinning is based on the mapmaker’s own beliefs and perspectives, his or her ethical propositions; his or her presuppositions dictate the result. Across a two-dimensional plane, maps reveal the results of our ethical choices in a landscape we understand as our own. Seen in this way, the map is the practical end point of an ethical supply chain that begins with a set of shared moral definitions and resulting injunctions that underlie propositions enacted in the construction of the mapped landscape. That underpinning expands from the map itself to the news stories that employ it or the journal articles that use it, not simply illustratively but substantially. But when that moral basis is that of the employer or speaker, not the mapmaker, he or she is often faced with an ethical disconnect. The work is his or hers, but its bias is not. Ethical and sometimes moral distress is the inevitable result.

This is not just about the map, or mapping. Maps serve here primarily as a medium for the exploration of the ethics and moralities that we embed in their construction. Charts and tables are others, as those used in previous chapters demonstrate. Nor does it matter overmuch if the maps, tables, or charts are being used by demographers, journalists, researchers, or statisticians. It is simply that in the mapping one can see more easily, and more dramatically, the limits of the methodologies by which we fashion ethical arguments and moral definitions.

For the deontologist, rules are preeminent. Those rules are designed to ensure a kind of social performance whose goals presumably reflect a particular moral perspective. When the result seems unethical or, worse, immoral, our role becomes that of a Gorgias or, at worst, simple drudges whose labors we would disavow if we could. The issue is not simply the efficacy of the rules—the way schools are funded; the way subways are constructed—but the manner in which they promote social outcomes that we seek either to embrace or to reject.

And so we come to the central insight of the American pragmatism advanced in the nineteenth century by the mathematician Charles Sanders Peirce. Its fundamental premise was that “in any kind of inquiry, we begin with an inherited set of beliefs, theories, principles, policies and practices.”6 They are the antecedents that determine what we investigate in the world and how we go about those investigations. Unless and until those antecedents are shown to be inadequate, they remain the basis of our investigations. And so like Hume, Peirce attempted to ground his argument in the concrete while acknowledging the conceptual baggage we all bring to a knowledge of the world.

To argue a pragmatist point of view is not to deny the ethical, or moral. Rather, it is to insist that they ride behind and below our decisions, influencing our choices and then our judgments. The trick, then, is to see how we chart or map the ideas that argue their presentation. The broadly pragmatic argues a complex rather than simplistic ethic, one in which everything is contingent on the moral suppositions we espouse and the propositions we believe result necessarily from them. There is no Olympian, independent observer to say, “Yes, that’s right,” because there is nothing but dynamic exchanges in which beliefs dictate actions that question or enforce beliefs.

In evaluating the efficacy of a belief set, Peirce argued, in a way Plato would have embraced, the first step was to perceive its consequences. “Consider the practical effects of the objects of your conception. Then, your conception of those effects is the whole of your conception of the object.”7 In effect, he proposed an if-then proposition based on a specific goals or value. The mind-set we bring to a problem or question, and thus its formulation, Peirce wrote, has three properties. First, it is something we must be aware of; second, it permits us to face the world with some surety; third, it establishes a habit of thought and a set of procedures or actions.8 When experience contradicts a settled belief, an ingrained habit, two things occur.

First, we have moral distress and, in extreme cases, moral injury, “that combination of emotional and cognitive consequences resulting from the commission, failure to prevent or intervene, or the observation of actions which constitute a violation of one’s core values.”9 That describes the “queasy feeling” in a nutshell: believing this, how can I/we act in that way? That was the dilemma the cartographers and statisticians confronted in the Tobacco Problem. If cancer limits human life, and if life is a moral value we embrace, then how can one take on the American Tobacco Consortium assignment without feeling queasy? What does it say about a nation’s morality when a national cancer atlas presents as complete data that are restricted to a single race? What does that say about us as citizens believing (at least in theory) in equality as a signal virtue?

The second and more general damage occurs when the ethical propositions we in theory embrace are demonstrably ignored in practice. Then “a patch of ground gives way,” and our moral suppositions are challenged, their power eroded. The ethical injunctions that would otherwise follow become empty rhetoric whose power to organize our world diminishes and then disappears.10 When moral definitions are eroded, the ethics that follow on them become inconsequential curiosities without any real-world substance.

What results is a thinly theoretical posture argued by those with little experience in the complex realities whose ethics of practice they seek to judge. For their part, professionals like the NACIS members have little knowledge of the means by which their ethical aspirations and moral sensibilities can be understood, let alone deployed in the experiential world.11 They just know what it’s like to take on a job they feel queasy about. Unlike Gorgias, they cannot take pride in the result.

Once one is comfortable with the idea of ethics and morals as underlying determinants, the nature of resulting debates about the world we present in our choices is shifted. We see these issues not simply as acceptable differences between individuals (“everybody has an opinion”) but from a shared social perspective of grounded collectively rather than eccentrically. This doesn’t mean all is necessarily clear. But where differences arise, their basis becomes obvious and can be a matter of focused debate.

In April 1992, I gave a talk titled “Reporting and Research in the Electronic Age” at the Poynter Institute, a journalism think tank in St. Petersburg, Florida. In those sessions, during what is now called the First Gulf War, an editor proudly showed attendees pages of his newspaper’s coverage of the “new soldier,” well equipped and ferociously motivated to extend American democratic ideals in the then new Iraqi conflict. “When my country goes to war,” the editor proudly told session participants, “so does my newspaper.”

Did that mean he would modify or withhold news reports of civilian casualties resulting from US military activities? Did that mean he simply repeated whatever officials said? Was his newspaper a civilian Stars and Stripes? Of course not, he replied. Journalistic integrity required truthful reportage. But, he continued, patriotism is every citizen’s ethical duty in times of war. If the United States is engaged in a moral battle for good, then those who criticize US troop activities are attacking the morally good. Patriotism became for this editor a defining social and journalistic virtue by which the truths his paper promoted were to be assessed. Not lying, of course. But where the truth was in question (and when is it not?), patriotism required that the government get the benefit of the doubt. That is how American soldiers from Kentucky, Mississippi, and Tennessee became “local” patriots in Iraq (see fig. 3.2).

When it was suggested that real patriotism and good journalism required skepticism, a critical rather than supportive voice, the editor was disconcerted. When asked if reflecting the official view didn’t make his paper a mere propaganda arm of the government rather than an at least semi-independent public voice, he grew irritated. And so the issue became the nature of patriotism as much as the role of the journalist in a nation’s conflicted roles.

We can map wealth as a source of pride and assume that the poor among us are of little consequence (“the business of government is business”). Alternately, we can map poverty and its consequences as a civil violation of promised equalities of opportunity (“the business of government is the health and security of its peoples”). Either way, we are mapping not simply data but an idea about what is important to us and to society. At the least, the morals underlying a map (or graph, or graphic, etc.), and its resulting ethics, may be identified and then considered on the basis of those suppositions and embedded presuppositions. Thus the first map calls on economic standards as its metric; the second calls on indices of education, health, and social franchise as its standard. The result of the latter approach is a pragmatic virtue ethic enforcing the idea of communal care over individual advance.

Peirce’s interest in the practical and its context was grounded in his desire to improve the theoretical. He was, after all, a logician and philosopher. Here the focus is reversed. My goal has been to focus on the practical by revealing its theoretical grounding. From this perspective, the difference between definitions of moral injury—operating at very different scales of interest—come into stark relief. There is the original, early twentieth-century definition of an injury to the nation by individuals whose lives do not measure up to some official standard. The needs and realities of those persons, even their very existence, could be dismissed in favor of a vision of the nation (healthy and strong) and its progress (idiots don’t help the bottom line, they breed more idiots). There is also the more modern definition in which moral injuries are visited on individuals tasked in the Hegelian sense through a conflict with the greater powers that be.

The first, today, is typically framed in economic terms. Ideas of community, mutual aid, and solidarity are quaint notions impeding the business of the nation. And so, to take one example, because the medical needs of an aging society are assumed to be expensive, some argue that those who are long-lived should be denied curative treatments.12 Ethically, good senior citizens “too old for health care” should willingly accept diminished care standards to promote the needs of younger persons.13 If they demur, not only is their patriotism questioned (selfish!) but their place within a society that defines its own health on the basis of economic standards (affordable versus unaffordable persons). But there is also the moral good that accrues over time to the individual in his or her need, and thus a sense of moral injury (some would say violation) when utilitarian ethical standards disastrously affect individual lives. Redlining neighborhoods may have made good banking sense, but the generations whose home prices were affected and whose mobility was restricted were injured by the practice. Funding education through local real estate taxes is efficient. That it has robbed generations of the education they require to be engaged citizens, well, so it goes.

And so from the start the conflict exists between an ethical yardstick that is broad and abstract and another that is individually focused and grounded in a morality whose suppositions advance from the start ideas of community and mutuality as central. It therefore is important to note—almost a conclusion—that with almost every example cited, allegiance to the second definition rather than the first presents consequential economic and social benefits. A communal morality (“We the people …”) is in almost all cases more efficient, less costly in any but the short term, and in the long run more beneficial to all. It is an argument and observation made time and again since the 1840s and the reformers quoted in Edwin Chadwick’s Inquiry into the Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population of Great Britain.14

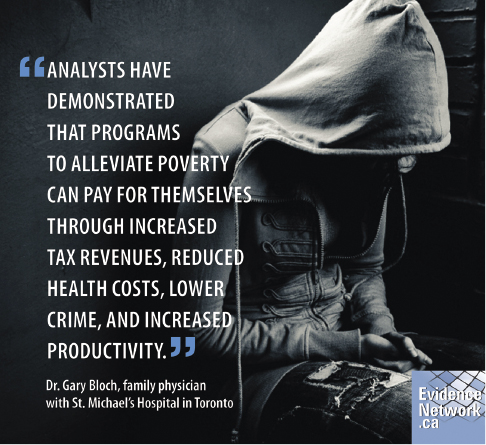

Diminishing poverty improves the health of persons and the health of society at large. It diminishes social costs of indigent care and of the even minimal care we feel obliged to provide to the unemployable frail, albeit grudgingly, as a society. Addressing systemic income inequality means a better, more engaged electorate as well as one whose members are more employable. That means more and higher taxes will be paid by working citizenry. Educational disadvantage results in poverty, and an electorate that is disengaged, devaluing democracy itself as a shared economic and social enterprise. The result is far more costly, in the end, than acting on the presupposed value of fairness and equality of opportunity for all.

Figure 10.2 A poster in Toronto, Canada, arguing poverty is more expensive than its elimination. Courtesy Folio Designs for EvidenceNetwork.ca.

In Toronto, Canada, where I live, researchers estimate that in 2016 poverty related to ill-health cost government at all levels an estimated Can $2.9 billion a year. Some put the total cost of city poverty (including diminished taxes and increased social support) at perhaps Can $5 billion annually.15 Nationally the calculated costs are far greater.16 And this is in Canada, with its commitment to both national healthcare and a moderately strong social safety net.

When poverty, educational failures, ill health, and unemployment are assumed to be simply objective data on a spreadsheet, the costly implications that result are usually implicit but hidden, the human suffering too easily ignored. But maps of inequality and poverty can be constructed to present opportunity surfaces for the promotion of greater communal good with positive long-term economic and social results. Rather than areas to avoid, they are sites to be engaged and improved for local and general long-term good.

We don’t tend to see them this way, perhaps, because we have forgotten Plato’s injunction that truth’s standard is not limited but broad, not individual but shared. The true phoneme of moral debate is not the individual or economics. It is the health and welfare of the citizenry at large. At least it is supposed to be. One problem has been, as the economist Julie Nelson observes, our assumption that capitalism is a kind of automatic machine obeying “inexorable and amoral ‘laws’” whose sole goal is profit, not care.17 It would be more accurate to say that capitalism as we conceive it today is on automatic drive along a course we chose and self-consciously set. Its algorithms are typically constituted to focus on the limited and the short term, on profit rather than the social good. It doesn’t have to be this way. It’s just the way it is until and unless we change our perception, alter our presuppositions, change our argument and thus our focus.

As Edmund Burke noted wryly, “It is far more easy to maintain a wrong cause, and to support paradoxical opinions to the satisfaction of a common auditory, than to establish a doubtful truth by solid and conclusive arguments.”18 It is easier for the economist to insist that he or she is simply observing the economic order rather than defining it and its costly results. It is similarly easier for the artist, cartographer, journalist, or statistician to ignore the ethical propositions of an assignment than to question them.

That, after all, is what most of us have been trained to do. We are taught that data are objective and facts are simple, observable things. We learn that the only appropriate question is whether the data we deploy are “true” and not a self-consciously fabricated, limited fiction. We are taught not to ask about the simple propositions (tobacco use encourages long life) the data were collected to argue. We are thus consequentially distanced from any deeper questioning of the research proposition’s suppositions. Relative poverty is just income variation; educational performance simply a record of high school graduation rates. A map of disease is no more than a snapshot of bacterial or viral incidence. Hurricanes are simply naturally destructive events.

We are thus schooled to ignore, at least until it becomes impossible to do so, the broader implications of this or that action or analysis and its relation to the moral definitions we as citizens believe, cherish, and are pledged (at least in theory) to promote. This blinkered agnosticism is the very definition of what we mean today by “professional.” The result is what Roland Barthes called a kind of “depoliticized speech” that “records facts or perceives values but refuses explanations: the order of the world can be seen as sufficient or ineffable, [but] it is never seen as significant.”19 And so we reject queasy moral concerns as unprofessional and substantive ethical concerns as irrelevancies divorced from the “real work,” the work we are paid to do.

That is, we do so until it is too late. The young soldier who believes in patriotism and service to the nation is damaged when that service requires he or she perform acts that seem personally unconscionable. The resulting post-traumatic stress, an inability to live with the distance between moral definitions and professional realities, damages his or her sense of ethical personhood. The engineer who did what he was told is damaged when a train crashes, a plane drops from the sky, or a shuttle explodes because preventable errors were recognized but not addressed. Those of us who face less-violent conflicts feel a similar if lesser disjunction, and pain, in our weighing of duty and morality. Where the result diminishes the collective good, the result is moral injury in its original sense, damage to the civil public at large. From this perspective, it is that collective good, expressed in our constitutions and conventions, which must stand as the yardstick of moral supposition and ethical proposition. That it is typically more cost-efficient and thus less injurious in the long run is an added if secondary boon.

Some may see this as a call to activism, to collectivism or socialism or some other -ism. It is instead a call to awareness, an insistence that we realize our choices matter. It asks that we see the potential effect of our work and in its preparation and presentation choose ethically and wisely. We may choose to be amoral rhetoricians free of ethical constraint, available to the highest bidder, or we may choose to acknowledge that our work is grounded in a moral framework that speaks consciously or by default to a communal good rather than simply individual advancement. We may argue that our only responsibility is to the rules others set or, alternately, to the idea of a kind of virtue ethic in which the person in society is our focus. We can choose to be like Gorgias, hired guns with allegiance only to this employer or that organization, or we can seek to be like Plato, for whom truth and its good were something more. If we choose the former path, we forfeit any ideal of substantive social responsibility; we ignore the sense of injury that occurs when our sense of personal ethics and morality is challenged by professional boundaries and commercial dictates. In so doing, we become mere mercenaries, carrying not a gun but a computer tablet.

For most of us, that is insufficient, unsatisfying to the point of moral distress. Virtue ethicists might say that’s how it should be because, for our own good and that of our communities, we should want to be more. There is in law the notion of the “predicate act” that necessarily results in specific outcomes.20 A landscape of poverty is the predicate that results in diminished educational funding, increased relative mortality, unrequited costs, and all those other things that follow on an impoverished, struggling citizenry. Because poverty is the predicate context of all these things, seeing a map of SAIPE-defined poverty, we should ask, “What is the result?” A map of disease invites questions about its causes and, if the disease is infectious, the likely pattern of its diffusion. It demands we ask about the preconditions that made a disease event inevitable and for which we as members of a society are at least in part responsible. If we let them, all or at least some charts, maps, tables, and stories open the same opportunity for critical questioning. And critical questioning, here, invites consideration of the ethical suppositions and their moral presuppositions as central to who we are and what we are to do as ethical citizens.

Figure 10.3 One doesn’t have to be a philosopher to “practice” philosophy. The issues it attempts to address pervade our worlds of family and work. That’s the message of this sign found on a telephone pole in Toronto, Canada. Author’s collection.

This is not to suggest we become a nation of philosophers schooled in a literature that stretches at least from Plato through Kant to Levinas (fig. 10.3). “A nation of philosophers is as little to be expected,” wrote James Madison in The Federalist Papers (1788), “as the philosophical race of kings.” But to say we need not be philosophers by trade does not mean we can ignore the philosophies we espouse as individuals and as citizens.

We need not create the world anew, constructing from scratch a morality and consequent ethics as if such a thing had never been done before. We need only refer to the declarations, covenants, laws, and policy reports in which moral presuppositions are presented in a manner that argues a guiding and practical ethic. This would mean that, like Plato, we think of the communal rather than the limited good and, with Kant, about the lives of individuals as more than anonymous rows in a statistical spreadsheet. In this way, we assert the consequentiality of our work as social beings. We then see that the morals we assert as a nation are those we must, as citizens, enact in our lives.

Here is John Rawls’s political ethic brought to the level of the practical. He argued that we need to see ourselves as if we are the subjects of the maps we make, the statistics we collect. We are the ones “behind the veil,” members of an event class symbolized by dots on a map. We need to think as if we were in the maps we make and read: denizens of Skid Row, Los Angeles, or a poor citizen in Mississippi unlikely to receive a graft organ but whose organs are solicited for the good of wealthier others. We don’t live in Owsley County, Kentucky (43 percent poverty), or in the poorest areas of downtown Buffalo, New York (90 percent nonwhite and poor). But we might. And thus we care about those persons as if we did because as citizens we are enjoined by the nation’s moral definitions to promote the general good and the best opportunities of a more perfect union. They are us, and we, as easily, could be them. That is what the community of citizenry means, in the end.

“It is easy to talk and write about human geographies of ethics and justice,” wrote Paul Cloke, “compared to the difficulties of living out those geographies in our everyday life practices.”21 To be more than rhetoricians means that we recognize the nature of our unease and accept our responsibilities as citizens within communities where we live, where we have a chance to be effective. It would be nice to think that pointing out the distance between our best ideals and our actual programs would be all that is needed. It is rarely that easy.

It is doubtful that ATC president Thomas J. Crawford would agree to stop the publicity campaign equating long-lived smokers with healthy long lives. It is even more doubtful that the hypothetical Raleigh, North Carolina, news editor would permit a reporter to write an article ripping apart Mr. Gleason’s talk as misleading piffle. It is unlikely that, as director of a small, struggling IT company, many of us would reflexively refuse the ATC contract. As Hegel knew full well, acting ethically has consequences, often unpleasant, for us as citizens trying to be virtuous and still get by in the world. The editor is beholden to bosses who are beholden to advertisers. The reporter is beholden to them all. The mapmaker has bills to pay, and to pay them, he or she must satisfy clients.

The result for the independent contractor and the salaried employee alike is the same: take the contract and feel guilty about the work; refuse it and be impoverished or, worse, unemployed. Either way, the result is “moral distress” in circumstances where “one knows the right thing to do, but institutional constraints make it nearly impossible to pursue the right course of action.”22 Those constraints result from a system of economic distribution and social governance that rarely rewards the ethical stance or the moral complaint. And so, in the Tobacco Problem, many discussants who approved the contract gave as their rationale “It’s legal and that’s all I need to know.” Sure, the result would be one in which they could take little pride; but if it’s not against the rules, as one person said charmingly, “baby needs new shoes.”

The very idea of moral distress has been debated widely in medical ethics, mostly in terms of how to assuage a professional’s unease rather than to address the underlying ethical dilemmas causing that distress. Some have sought to offer “conceptual and theoretical clarity.”23 The clarity typically offered parses the individual’s distress and not the context that gave rise to it. And so, with that perspective, nothing changes at all.

I first encountered this in 2001 when I was hired to spend a day lecturing about bioethics to Ottawa hospital social workers. I spent the first hour reviewing the history of medical ethics and the second describing their general principles of application. In the third hour, I asked what problems the social workers saw as ethically troublesome. After all, they had hired me. It seemed the least I could do was ask what might we discuss together. All agreed the single greatest problem was that supervisors directed them to free up hospital beds by sending fragile seniors to any assisted-care facility with an open bed, even if the social workers believed the assignment was, for a particular patient, inappropriate. The problem isn’t limited to their hospitals and remains exigent in many places today.

The social workers wanted to delay the transfers until more appropriate placements were available. Their responsibility, they said—personally and professionally—was to the patient’s best interests and safety. An inappropriate discharge was, for them, a failure. The hospital, however, wanted these patients relocated to free beds for new and urgent cases. The hospital, after all, isn’t supposed to be a long- or even mid-term care facility.24

Canadian hospitals are provincially funded and supervised and neither private nor “not-for-profit” institutions. Long-term care facilities are in theory regulated by provincial health ministries but are often privately owned and operated. While there is general agreement that patients needing longer-term care facilities should not remain overlong in much needed, acute care beds, the supply of affordable longer-term residence facilities is a chronic problem.

As we discussed the issue, their superior came into the room. Wearing a terrific three-piece suit below a sculpted haircut, the director for patient services (or some such title) shook my hand and warmly thanked me for sharing my knowledge with his social workers (who themselves paid my expenses and a small honorarium). He was sure they had learned a lot, and as a hospital official, he was grateful for my efforts. I told him I was learning from them, as well.

“Perhaps you can help us with something,” I said. In discussing ethics as a real thing, I continued, there was this problem of the expeditious forced transfer of patients in a manner that in the professional opinion of the assembled social workers was inappropriate and potentially injurious to patients. What did he think “his” social workers should do when official directives violated their professional standards and sense of ethical responsibility?

“That doesn’t happen,” the supervisor assured me. A brief, short-term allocation problem had been rectified. Everything was fine. All assignments were, if not optimal, then more than acceptable. With that pronouncement and a quick final handshake, he departed. The social workers laughed, shaking their heads at my foolishness. “Well, you won’t be coming back,” one said to me. “So,” another asked, “what do we do now?” Some talked of quitting, or at least moving to other institutions if not other professions where they would not feel queasy at the end of the day.

“Often, the underlying issue in moral distress is the gap between being responsible for delivering care and having the authority to determine what that care should be.”25 And so we talked about the problem. The social workers could point to professional ethics statements, hospital policy declarations, and, if they wished, broad political proclamations to support their views of what should be done. But while their responsibility as social workers was to the patients, as employees they were in liege to the institution and its policies. They had mortgages and car payments and kids in school. Like the Map-Off Ltd. participants, they needed their jobs.

We talked about documenting the problem. They could map the imbalance between demand and supply in assisted-care facilities and nursing homes, mapping the distance between discharge locations and family homes to show how many patients being discharged were, as a result, being isolated from their personal support communities. We discussed the possibility of union action (“Not our union,” they laughed, “they don’t do social”). We talked about involving local media. We talked about putting the problem before their elected members of the provincial legislature if not also their Parliamentary representatives. But any of those actions would have resulted, if not in their firing, they said, in their being condemned as whistle-blowing malcontents with a dismal work future.

It’s one thing to see what is needed, I said. It’s a very different thing to fight for it. That means documenting the problem in the context of the promises we make as a society or, in this case, a professional organization whose members, in theory, have a duty to care. But documentation is only the beginning. To act on it is to invite censure. Hegel knew that. It’s why he called it tragedy.

It is hard to turn down work that is needed to pay the bills, to challenge a boss whose choices are inappropriate. Sometimes that is what one does because if one does not, it is hard to look in the mirror. And so I return here to where I began, with one change. Ethics is about our whole manner of being, not simply as individuals but as citizens in communities we seek to serve. We are responsible, as such, for not simply our own character but that of the community as well. Understanding what is right or wrong, what to condemn and what to promote, is not impossible. It may be uncomfortable and, in the short term, seem impractical but to ignore that understanding whatever the cost is to deny our own sense of rectitude and self. “If the tradition of the virtues was able to survive the horrors of the last dark ages,” wrote Alasdair MacIntyre, “we are not entirely without grounds for hope.”26

Across the longue durée of history, we have heard, time and again, a call for Aquinas’s conscientia, a governing conscience over the immediate and pedestrian needs of the moment. It is not simply that, as Montaigne insisted, “life should be an aim to itself, a purpose unto itself,” but more particularly that purpose is or should be a good life in Plato’s sense, one serving the community at large rather than the particular needs of the self-serving moment. The goal here has been to insist on that possibility while mapping the effects of its failure both on us, in our distress, and on society at large.

The choice is yours. But please remember: your choice will affect us all.