The olfactory pathway can act alone when we smell the aromas of food or beverages by inhaling them by the orthonasal route. When smells arise from food in the mouth to make their contribution to flavor, they always act on the brain in concert with other systems. We need to keep reminding ourselves that in addition to the sense of smell being a dual system—orthonasal smell and retronasal smell—retronasal smell is never sensed by itself, but always together with virtually every other sense in the mouth. It is the basis for my claim that flavor is among the most complex of our perceptions created by our brains. As Frédéric Brochet and Denis Dubourdieu in Bordeaux note: “[T]he taste of a molecule, or of a blend of molecules, is constructed within the brain of a taster.”

The most obvious sensory system contributing to “taste” is the taste system, the one that gets all the credit for the resulting flavor.

Taste Buds

As we all know, this system begins with stimulation by food and drink of the taste buds on the tongue and the back of the mouth. They are called buds because they consist of taste cells crammed together to make a kind of bud, or cartridge, with each sensory cell ending in fine hairs that carry receptors for different stimuli. The taste buds are located in different-size folds (papillae) of the tongue surface. If you look in a mirror with your tongue out, and especially if you paint it with a food dye, you can see small mushroomlike (fungiform) papillae in the middle of the tongue, medium folds (foliate papillae) on the sides at the back, and large round (circumvallate) papillae in the middle across the back.

The Molecular Basis of Taste

The taste buds contain cells that respond differentially to five kinds of stimuli. The traditional ones in Western culture have been salts, acids, sugars, and bitter compounds. Asian people traditionally identify a fifth type of stimulus, the amino acid glutamate, which they link to a meatlike perception called umami. This is now widely accepted as a basic taste, often termed savory or meatlike.

Each type of stimulus acts preferentially on a special type of receptor (box 13.1). Molecular biologists have used gene engineering to clone and identify these different taste channels and receptors. Just as with the olfactory receptors, taste receptors are fundamental to molecular neurogastronomy.

BOX 13.1

Basic Taste Stimuli and Their Receptors

Salts act on a membrane channel that lets salt ions (sodium or potassium) flow through it.

Acids act on a membrane channel to modulate hydrogen ion flow through it.

Sugars act on sugar receptors (Taste Receptor Type 1, subtype 1 and 3: T1R2 and T1R3) that activate a second messenger system involving cyclic adenosine monophosphate (AMP).

Bitter compounds act on special bitter receptors that are also linked to a second messenger system called gustducin. The bitter receptor gene family (Taste Receptors Type 2: TAS2Rs) is numerous and diverse (more than 100 genes), reflecting their important role in detecting as many substances as possible that might be harmful to the organism.

Umami is due to the carboxylate anion of the amino acid L-glutamate (monosodium glutamate) found in broths and meats; it stimulates receptors called T1R1/T1R3 that are linked to second messengers.

Encoding Taste

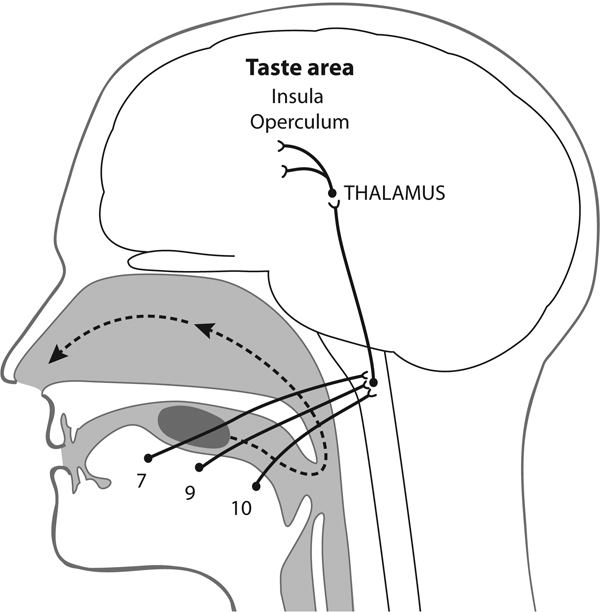

The receptor cells in the taste bud have no axons to carry their responses to the brain, unlike the olfactory receptor cells. The cells interact with one another and with the endings of three types of nerve: the seventh, ninth, and tenth cranial nerves. The reason for mentioning them by their numbers is to highlight the fact that they are toward the back in the series of twelve cranial nerves beginning with the first nerve, the olfactory nerve.

The taste nerves enter the brain stem, the part of the brain that is directly continuous with the spinal cord and that is responsible for automatic functions such as control of heart rate, breathing, and other vital activities. There is thus a sharp contrast with the olfactory nerves that enter the front of the brain closest to the highest cognitive centers. It is as if the multisensory flavor sensation is designed to allow ingested foods to be analyzed at both the highest cognitive level as well as at the level of the most vital functions. It has all bets covered.

How the different kinds of taste are represented in the brain has stimulated two basic views. One, supported by psychophysicists who test subjects for their responses, is that each type of stimulus has its labeled line into the brain, leading to its distinct perception. This was called the labeled line theory. The other view, held by physiologists making recordings from the nerves, was that a nerve fiber tends to respond best to one type of taste stimulus, but that it also responds to two or three of the others to less of an extent. This is called an across-fiber pattern and indicates that there is a limited kind of combinatorial processing of the taste input. With gene engineering, Charles Zuker at Columbia University and other molecular biologists have been able to delete each type of receptor shown in box 13.1 and show that in most cases a given type of receptor is responsible for most (but not necessarily all) of its appropriate taste perception.

In the brain stem, the fibers connect to a group of cells called the nucleus of the solitary tract. From there the pathway in the primate goes to the taste nucleus in the thalamus, where it is relayed to the taste area of the cerebral cortex. The primary cortical taste areas in the primate, including humans, are the anterior insula and nearby frontal operculum. Insula refers to the island of cortex inside the folds of the cerebral cortex; operculum refers to the folds that cover it. It is in these areas that conscious perception of taste is believed to occur (figure 13.1).

FIGURE 13.1 The human taste system

7 = facial nerve; 9 = glossopharyngeal nerve; 10 = vagus nerve.

Taste Qualities

At the highest level of conscious perception, we classify the five basic taste sensations as salt, sour, sweet, bitter, and savory (umami)—the four s’s and a b (box 13.2). Note that these are not exactly the terms we used to describe the taste stimuli themselves. There is not, in fact, a direct mapping of those stimuli into corresponding sensations. For example, sweet has its major contribution from sugar receptors but also smaller contributions from the other types of receptors, and sour likewise has its major input from acid receptors but also contributions from the other receptors. This reflects a limited combinatorial processing that takes place between the taste stimuli and the different taste receptor mechanisms, resulting in perceptual qualities that are multidimensional rather than one-dimensional.

BOX 13.2

Basic Taste Perceptual Qualities and Significance

Saltiness is essential for maintaining salty body fluids derived from mammals’ sea ancestry.

Sweetness is innate in all mammals, because sugars reliably signal high energy. Mother’s milk and ripe fruits are sweet.

Sourness warns of food that may have gone bad.

Bitterness warns of toxic substances that should be rejected.

Savoriness is a meaty quality, signaling a high-energy food.

Box 13.2 indicates only the simplest qualities associated with each type of taste stimulus, also called a “tastant.” In fact, especially in human diets, any quality can be attractive, depending on the combination of qualities of a particular food or drink. Thus, although sweet is often considered the most attractive taste quality for humans, there are also among human cuisines preferences for salted meat, sour cream, bitter chocolate, and untold variations on these themes. Each of these tastes is accompanied by smell images that have become attractive through the learning process of growing up in a particular culture.

These basic tastes have powerful interactions with the other senses that make up flavor. Sweet and salt also strongly enhance food preferences, ranging from liking to craving. (For more on overeating associated with food that has an irresistible taste, see chapter 21.)

A Cortical Taste Map?

The ability to record the responses of nerve cells in cortical areas of the monkey has enabled investigators to confirm that cortical cells respond to tastants, presumably associated with the conscious responses. One might assume that because each tastant gives rise to its distinctive perception, there would be “labeled lines” in the taste pathway to spots in the taste cortex reserved for each quality. Thus far the evidence for such a map in the taste areas has been equivocal. So it is possible that at the cortical level the taste qualities are represented in a more associative manner similar to that in the olfactory cortex and the association cortical areas of other sensory systems.

Cortical Taste Responses

Each tastant has its threshold—its minimum concentration—for eliciting a response when given individually. However, as Justus Verhagen and Lina Engelen at the John B. Pierce Laboratory and Yale University explain in an extensive review in 2006 of these kinds of interactions, if two or more tastants are given together, there is an interesting effect: the threshold for the mixture is lowered, and the subject is able to detect the mixture when the individual tastants are weaker. This means that each weak tastant cannot be sensed by itself, but together they can be perceived (for example, salt and sour). This is called intramodal enhancement.

Cross-model enhancement occurs between sensory systems. This is particularly interesting for taste and smell interactions. A weak smell and weak taste can be subthreshold by themselves, but together they can be sensed, although usually only if they are “congruent”—that is, if they complement each other. Congruency may be innate, or it may be learned. Noncongruent smell and taste stimuli do not have this mutually enhancing effect.

The effect of one stimulus enhancing another is believed to be of survival value for the animal. For humans, it has the interesting implication that the more sensory elements there are in our foods, the more it enhances their flavor. Our traditional cuisines consist of multiple different sensory stimuli that, one may hypothesize, usually are congruent.

In contrast, modern “molecular gastronomy” often explicitly experiments with combinations of senses that are not congruent. In these cases it may well be that two or more different senses in a food are not congruent and therefore do not enhance each other. Conversely, this incongruent effect may be precisely the aim of the mixture: to give an entirely new and different flavor perception.

Taste and Retronasal Smell Together

Taste stimuli usually occur together with retronasal smells. In fact, smell and taste together are often regarded as forming the main basis of flavor. If it is important to be able to detect this co-stimulation, it should not be surprising that orbitofrontal neurons are found that respond to both taste and smell stimuli. The two sensations are so closely related that in some cases smells take on the qualities of taste, as when one says that something smells sweet. This is called sensory fusion, regarded by some as an example of synesthesia, defined in chapter 12 as interpreting the quality of one type of sensory stimulus in terms of another sense: an odor smells sweet; a sweet taste is blue.

The cells in these primary taste areas have been shown to be sensitive not only to taste but also to other senses, such as texture and temperature. Some cells respond only to taste, whereas others respond to the other modalities. We see here the neural signs of how the cortex builds the multimodal nature of flavor.

Apart from the effect of taste and retronasal smell together on responses in the primary cortical areas, a striking finding is that together they also enlarge the amount of cerebral cortex that is activated. This was shown in a classic experiment by Dana Small and her colleagues in 2005. They first stimulated subjects separately with a retronasal smell and with a tastant, which activated the two primary cortical receiving areas, as shown by functional imaging. They then delivered the two stimuli simultaneously, as would happen during ingestion of a food. This activated not only the primary areas but also previously unstimulated secondary surrounding areas of the cortex. Presumably these added areas were recruited to analyze the more complex mixed stimuli. The cortical responses combine taste and smell to create the unified quality of flavor.

Taste and Emotion

We know that tastes are strong elicitors of emotion. The most marked facial expressions of pleasure or disgust come from tasting foods that please or repulse. The facial expressions reflect what is called the hedonic (emotional) quality of the food.

Are these hedonic qualities hardwired or are they learned? Jacob Steiner, a pediatrician in Israel, set out in 1974 to test whether the hedonic properties of the different tastants are present at birth—in other words, whether they are hardwired or have to be learned by experience. He arranged to test newborn infants in a hospital in the first hour or two after birth before they had exposure to any taste, and to film their facial expressions.

The results were dramatic. When testing with a cotton swab dipped in a salt solution, the infants showed little facial response, just looking around and wondering what a curious world they had been born into. When tested with an acid, they showed a definite aversive puckering of the lips. A bitter substance produced a face of disgust and distress with an open mouth trying to eject the substance. Finally, it all turned out wonderfully, because sugar elicited a fleeting but unmistakable smile.

The implications of this experiment are quite interesting. They show that the basic emotional (hedonic) qualities of the tastants are hardwired at birth. The infant does not have to learn that sugar is good, salt is fine, acid is not so good, and bitter is to be rejected. This makes adaptive sense for the survival of the organism. But even more interesting is that the basic emotions of happiness and unhappiness are present at birth. We do not have to learn how to express these fundamental emotions. This also makes adaptive sense for the bonding of infant and parent. Expressions of affection and disapproval are unambiguous in forming the new relation, and they continue in their basic form throughout childhood and adult life.

These results in the human were confirmed by Ralph Norgren and his colleagues at Penn State University in experiments on infant rat pups, which show the same types of responses to the same types of stimulants. Furthermore, in the rats it was possible to test more directly the important question of whether the hedonic responses are mediated entirely at the brain stem level or might include some higher brain processing, by carrying out experiments removing just the brain cortex. The basic responses were not affected, showing that the hedonic responses are hardwired only at the brain stem level. As we noted, this is where the taste fibers enter the central nervous system.

In summary, the taste system builds hardwired emotional expressions for its attractive and repellent stimuli. This means that when we experience a flavor we really like, our happiness is expressed through facial expressions laid down at birth and co-opted by smell. This provides a foundation for further consideration of the emotions of flavor in chapter 19.

Supertasters

We assume that everyone has the same sensations of taste we do, but this is not true. Amazingly, Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin already knew this:

I have already stated that the sense of taste resides mainly in the papillae of the tongue. Now the study of anatomy teaches us that all tongues are not equally endowed with these taste buds, so that some may possess even three times as many of them as others. This circumstance explains why, of two diners seated at the same table, one is delightfully affected by it, while the other seems almost to force himself to eat; the latter has a tongue but thinly paved with papillae, which proves that the empire of taste may also have its blind and its deaf subjects.

Brillat-Savarin is describing what we now call individual variation. He was remarkably prescient. The most studied variation in taste is the ability to taste the bitterness of a particular bitter compound called propylthiouracil, or PROP for short. Linda Bartoshuk, formerly at Yale and now at the University of Florida, coined the term supertasters, characterized as individuals who taste PROP as extremely bitter and those who have the highest density of fungiform papillae on the tongue tip.

Bartoshuk, her longtime collaborator Valerie Duffy at the University of Connecticut, and other colleagues have built on the groundwork laid by Roland Fischer in the 1960s to explain variability in food preferences, alcohol consumption, and body weight, based on their data from PROP tasting, fungiform papillae density, and other taste markers, such as the bitterness of quinine. Steven Wooding and Dennis Drayna at the National Institutes of Health in 2004 discovered the gene that is responsible for 70 percent of the variation in the bitterness of PROP. Since then, more of the taste receptor genes have been paired with the ability to taste bitterness of specific bitter compounds, including coffee and grapefruit juice.

According to Duffy, she and others are studying a variety of tastes and taste genes to identify individual variation in taste and link this variation to diet and health outcomes. For example, nontasters to PROP or those carrying receptors with lower response to bitter compounds appear to like fat, sweet foods, and alcoholic beverages; are heavier; and are at greater risk of alcohol overconsumption. By contrast, supertasters report greater disliking for vegetables and tend to be thinner. PROP sensitivity is associated with a higher taste sensitivity in general, and with a larger number of taste buds on the tongue. You can inspect your tongue in the mirror and see if you are a supertaster. If you are, be assured that this is a normal variation in the population. But it is something to keep in mind when you sit down to your next dinner: Are you experiencing more or less of the taste than your dinner companions? In sum, to paraphrase Brillat-Savarin: Tell me your bitter receptor genes, and I will tell you who you are.

Bait Shyness

An important aspect of taste is that it is the critical line of defense against the ingestion of stuff that would be bad for us. Stuff that is poisonous is usually bitter, for which the bitter taste receptors are tuned. But what about a pleasant-tasting food that turns out to have harbored an infective agent that makes an animal sick or was used as bait to lure an animal into a trap? In a famous study, John Garcia and Robert Koelling showed in 1966 that an animal that has been made sick from a food just once will avoid that food ever after, even though the sickness occurs many hours later. It is called conditioned taste aversion; in field studies of animals it is called bait shyness. Because it requires only one episode of sickness, it is also called one-trial learning.

Bait shyness is so much more powerful than classical learning, which involves many paired associations between stimuli, that at first few psychologists believed it. One of them who reviewed Garcia and Koelling’s first article was quoted as commenting: “These findings are no more likely than finding bird s——in a cuckoo clock!” But we are all familiar with this kind of learning. When we suspect a food has made us sick, we lose our taste for it and search through our memories for the cause of it. It has also been called the Béarnaise sauce phenomenon after causing sickness in a well-known psychologist. In subtle forms it may lurk behind food phobias that develop during childhood and in some cases last a lifetime.