To appreciate how humans are adapted for retronasal smell, it is useful to compare us with one of the acknowledged champions of smell: man’s best friend, the dog. To compare the two, it is necessary to understand how each is engineered to serve its functions best. It will be no surprise that the dog’s nose is an engineer’s dream. But what about the human’s? Are we as poor as Aristotle believed? The take-home message is that dogs are adapted primarily for sniffing in smells of the environment, whereas humans are adapted primarily for sensing smell as the main feature of flavor. Thus the dog’s nose is engineered mainly for orthonasal smell, and the human nose is engineered mainly for retronasal smell. This is how the human nose fulfills its role as the key player in neurogastronomy.

Fluid Dynamics of Inspired and Expired Odorized Air

Gary Settles is professor of mechanical engineering at Pennsylvania State University. He specializes in the field of fluid dynamics, which concerns itself with the way that air or water act when passing over wings or forced through tubes. This field involves not only understanding and designing efficient wings for airplanes, nozzles for jet blowers, and ventilators for homes, but also how to draw air into devices used to detect trace substances such as explosives that might be present in cargo in container ships and in narcotics in suitcases. The latter interest led him to study how nature does it through the snout of a dog. “The Aerodynamics of Canine Olfaction for Unexploded Ordnance Detection” is the title of one of his recent research projects.

A while ago I attended a lecture in which Settles explained the fluid dynamics of the dog’s snout. He began by pointing out that studies of mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) from fossils support the notion that dog-like animals—including the wolf, fox, raccoon, bear, weasel, and jackal—arose around 50 million years ago in the mammalian line. This is about the time that the early monkeys were emerging in the primate line. Like other mammals, the dog-like animals moved air in and out through their noses by means of the bellows-like action of the respiratory muscles on the lungs. An exquisite coordination between smelling and breathing was thus required.

Breathing in to sample the scent in the air is what everyone knows as sniffing, and the dog is beautifully designed for this function. The design begins with the nostrils, technically called the nares. If you look directly at your dog’s snout, you will see that its nostril opening has a peculiar shape, with a central round opening encircled by membranes called alar folds and a curved slit to the side; it has been likened to the form of a comma lying on its side. When a dog sniffs the ground, it draws in air through the central opening by muscles of the alar folds that enlarge the opening, but it breathes out by contracting other muscles that direct the outflow through the slits to the side. The singular advantage of this arrangement is that the air breathed out does not interfere with the odorized air that is being breathed in. This is particularly important as the tip of the nose gets closer to the ground. Here is how Settles describes it:

The expired air jets… are vectored by the shape of the “nozzle” formed by the alar fold and the flared nostril wings…. Thus the external naris acts as a variable-geometry flow diverter. This has three advantages: (1) it avoids distributing the scent source by expiring back toward it; (2) it stirs up particles that may be subsequently inspired and sensed as part of the olfactory process; and (3) it entrains the surrounding air into the vectored expired jets… thus creating an air current toward the naris from points rostral [in front of] to it. This “ejector effect”… is an aid to olfaction; “jet-assisted olfaction,” in other words.

It can be shown that when a dog sniffs the surrounding air, the sniff draws in air from a sphere about 4 inches (10 cm) around the opening of the nares. This is called the reach of the nose, for detecting odor molecules at low concentration in the surrounding air. When a dog senses the air, it changes to long inspirations, with its mouth open, in order to draw air over the olfactory membranes inside the nose slowly for careful detection. This is the way smell is used by dogs that are “pointing” after detecting the scent of a prey.

For detecting odors on the ground, the dog wants to decrease the reach distance as much as possible, which is why it has its nose virtually touching the ground when it is keen on following a scent there. The shorter distance makes the lines of air flow denser, enhancing the concentration of the inspired odor molecules. Settles has carefully charted the lines of air flow, converging on the nares inlets in the center and diverging from the slits to the side; it is a beautifully designed system for tracking scents. It enhances the high acuity of smell the way that the central fovea of the eye enhances high acuity of vision.

Settles goes further to analyze the way a dog uses this system in concert with its vision to inspect a new sense source. The dog first gets its nostrils down on the ground and sniffs its way to the scent source, following the increasing concentration until it reaches a maximum and begins to decline. It continues to sniff over and around the source; this action also enables it to inspect the source visually. The expired air plays its own role, with the lateral jets disturbing the source area enough to raise small clouds of particles that carry more odorous substances to the nares for inhaling.

Note that the dog’s nose is as much a motor as a sensory organ, carrying out several motor functions: (1) acting on the environment to dislodge odors from their carriers, (2) adjusting the proximity of the nares to enhance the concentration of odors from odor sources, and (3) separating the inspiration from the expiration of odorous air to achieve the most effective balance.

The kinds of odor that a dog smells are very much a reflection of the position of this detector apparatus. In the dog, as in most terrestrial animals, standing on four legs means that the head is not far from the ground, so putting the nostrils to the ground is a natural movement, even in larger animals. The four legs also mean that the head and the hips are about level with each other. This has immediate consequences for social interactions between members of the species, because it means that when two individuals greet each other their odor detectors are not only at the same level for sniffing each other’s head ends but also at the same level of each other’s rear ends. Thus it is natural for dogs to leave olfactory calling cards at both ends. The same principles of maximizing odor concentration by minimizing distance apply, accounting for the intimate interactions of dogs greeting each other. It is interesting that by this means dogs acquaint themselves not only with mouth odors, signaling what has been consumed, but also with fecal and urine odors, signaling what has been digested and gone out. Through these odors they also learn of hormonal status and sexual receptivity.

So far I have discussed only the nostrils. What happens inside the snout?

Inside the Snout

Nearly all animals have some kind of a snout extending from between the eyes, containing the mouth and a cavity lined with the sensory cells for smell. In fish, frogs, and reptiles this is a simple cavity, with the odor molecules coming in through the water in the case of fish and both water and air in the case of amphibians and reptiles, directly onto the sensory cells. A long nerve tract arising from the receptor cells connects the sac to the olfactory bulb that connects to the brain. By the way, the long snout of the alligator is not long because of a long nasal cavity inside, but because the upper jaw carries a long row of teeth for crunching its prey.

When mammals arose over 200 million years ago, they are believed to have been small animals, like present-day mice or rats. Their snouts were one of their most essential adaptations to terrestrial life. In contrast to those of alligators, these were true snouts, containing an extended nasal cavity all the way out to the tip.

In a modern mammal such as the dog, the olfactory receptors are confined to the back of the nasal cavity, usually lining a series of bony convolutions in order to increase the extent of the sensory sheet (figure 2.1). In between the nostrils and the receptors is a remarkable additional organ, a kind of a cartridge even more highly convoluted and covered by respiratory membrane. In technical language, these convolutions are formed by the ethmo- and maxillo-turbinal bones.

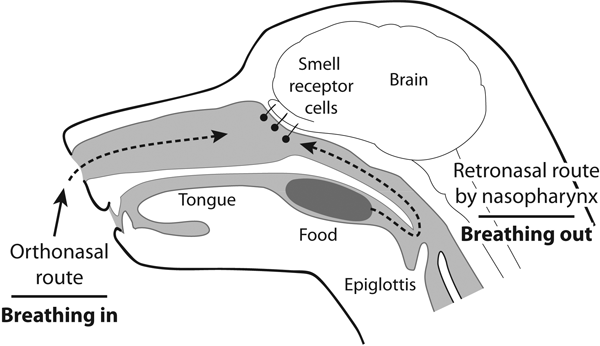

FIGURE 2.1 The head of a dog

The arrows show the pathways for sniffing smells by the orthonasal route and for sensing smells from the mouth by the retronasal route. Note the long length of the retronasal route from the mouth to the smell receptor cells.

Victor Negus, a British specialist in ear, nose, and throat diseases, spent many years writing what is now the classical treatise on the structure of the snout in different animals in order to compare and contrast it with the human nose. He showed that the cartridge serves as a kind of air filter or air conditioning system, with three functions: warming, moisturizing, and cleaning. Warming the inhaled air brings it into equilibrium with the temperature of the air in the respiratory tract. Moisturizing the air brings it into equilibrium with the moist air in the respiratory tract. Cleaning the air removes inhaled materials, such as bacteria, smoke, and particulate matter. Negus examined many different kinds of mammals and found the filtering apparatus to be present to a greater or lesser extent in all of them, with one notable exception: primates, including humans.

Just as the muscles of the nostril manipulate the inhalation of air, so are they coordinated to direct the air streams into the snout. One direction is through the middle of the air-conditioning cartridge during quiet breathing. The other is a redirection more to the side of the cartridge so that air more quickly reaches the olfactory sensory sheet, called the olfactory epithelium, at the back of the nasal cavity, where active sensing occurs.

When a dog is actively sniffing an object, the rate of sniffing increases dramatically, from one or two respirations a second to as many as six to eight a second (small rodents like mice and rats can go even higher, to ten to twelve a second). This is much faster than a human can sniff; you can test yourself and see that the limit is about four a second.

In contrast to these adaptations for enhancing orthonasal smell, the diagram shows that the pathway for retronasal smell, from the back of the mouth through the nasopharynx to the nasal cavity, is long and relatively narrow. The dog thus appears to be preferentially adapted for orthonasal smell. What about humans?

Evolution of the Human Nose

The evolution of humans involved lifting away from the noxious ground environment as they adopted a bipedal posture. This reduced exposure of sensory cells to infections. The complicated air-cleaning apparatus thus came under decreased adaptive pressure, reducing the loss of absorbed odor molecules. The large extent of olfactory receptor cell epithelium and abundant numbers of olfactory receptors present in most mammals would have come under reduced adaptive pressure and were accordingly reduced in proportion. The result was the elimination of a snout and nearly all the air cleaning apparatus, leaving our relatively modest outward nose and inside nasal cavity.

Although this explanation seems logical, arguments from evolution are notoriously speculative. Another perspective on the evolution of the human nose is that it had less to do with the reduction of the sense of smell and more to do with the reduction of the maxilla and mandible as primates and early humans adopted a diet with less roughage.

These developments meant that the snout could be reduced in dimensions and complexity without compromising the absolute amounts of odorized air reaching the olfactory epithelium. A widely accepted scenario is that as the snout lessened in size it allowed the eyes to come forward and lie closer together to promote more effective stereoscopic vision. This supposedly allowed human evolution to be dominated by vision at the expense of smell, providing the popular explanation for how we ended up with a weak sense of smell. However, the recognition of the importance of retronasal smell for humans makes this argument irrelevant. In our new view, the reduction in orthonasal olfaction is not the key; the key is, rather, the relation of the nasal cavity to the back of the mouth, which served to enhance retronasal smell in humans.

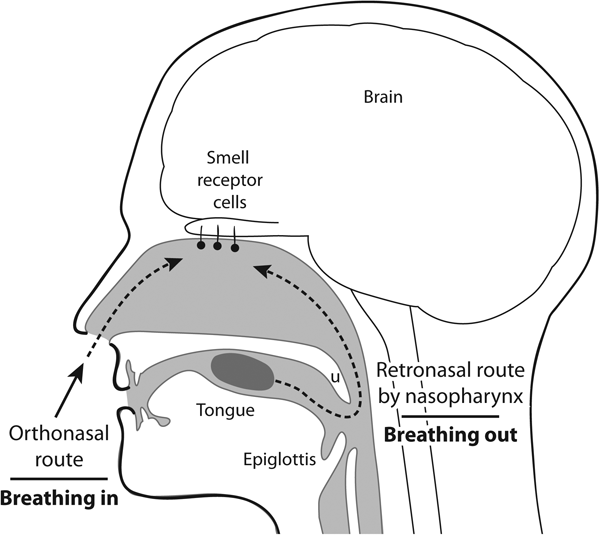

Comparing the dog and the human shows how dramatically they differ in this respect. The dog is characterized by its elaborate cleaning apparatus for orthonasal smell, and by the long tube, the nasopharynx, connecting its nasal cavity to its pharynx at the back of the mouth for retronasal smell. The human, by contrast, is characterized by the short distance for orthonasal smell and, most importantly, the short nasopharynx for retronasal smell as well (figure 2.2). The latter is the key passageway for enabling odors released from food in the mouth to reach the smell receptors in the nasal cavity. It provides direct evidence that the human is adapted for much more effective retronasal smell than the dog and other mammals.

The retronasal route to the smell organ begins with the food or drink that comes into the mouth. There the food is moved about by the tongue as it is chewed (masticated). It is said that only the human can roll its tongue, an ability that may impart special capabilities in manipulating food as it is chewed and sensed. At the same time, the taste is sampled by the taste buds on the tongue and the back of the mouth and into the pharynx. When the chewer exhales, air is forced from the lungs up through the open epiglottis into the nasopharynx at the back of the mouth. There the air absorbs odors from the food that coats the walls and back of the tongue and that have volatilized from the warm, moist, masticated mass. Because the mouth is closed, the odor-laden air is pushed into the back of the nasal chamber and out through the nostrils, sending eddy currents within the nasal chamber up to the olfactory sensory neurons to stimulate them.

FIGURE 2.2 The head of a human

The arrows show the pathways in humans for sniffing smells by the orthonasal route and for sensing smells from the mouth by the retronasal route. Note that the pathways are relatively direct compared with those of dogs.

How might retronasal smell in the human compare with that in the dog? I know of no studies of how effective the passage of air is from the back of the dog’s mouth through this long, narrow nasopharynx to the olfactory epithelium, so one can only speculate that the passage is less effective than in the human, where the distance is relatively short and the opening is relatively large. On this basis, one can hypothesize that the human nasopharynx is adapted for enhancing retronasal smell.

There are several reasons why retronasal smell may be especially important for humans, perhaps uniquely so:

These developments occurred among the early hunter-gatherer human cultures and lasted through the last ice age. With the transition to agricultural and urban cultures around 10,000 years ago, human cuisines expanded and stabilized through the addition of products from domesticated animals, plant cultivation, use of spices, and complex procedures such as those for making cheeses and wines, all of which produced foodstuffs that especially stimulate the smell receptors in the nose through the retronasal route and contribute to complex flavors.

These considerations suggest the hypothesis that the retronasal route for smells has delivered a richer repertoire of flavors in humans than in subhuman primates, dogs, and other mammals. On this basis, I postulate that this system in the human brain played a much more important role in the evolution of early humans than has been realized, as well as a much more important role in our daily lives (including my daily home dinner).