FOR Ron Williams, it was the beginning of a new beginning. Warmed by summer’s setting sun and a rare inner glow of satisfaction, he stood on an isolated beach in Western Australia, indulging his passion for surf fishing. He was – if not a world – then at least a continent away from decades of disappointment.

For the first time in years the battler from Melbourne could see a future that gave him hope for a better life.

No longer would he struggle in low-paid jobs, a potential casualty in every economic downturn. He felt he was going to crack the big time and become, finally, master of his own destiny.

Standing next to Williams on the deserted beach near Albany, was his new boss and confidant, a man who called himself Paul Jacobs, a successful company director and the driving force behind a national geological firm.

Although the two were the same age and physically similar, Ron Williams looked up to the man he’d known only a few weeks for having the qualities he lacked – drive, ambition and a sense of purpose.

Until they met, Williams had been convinced he was going nowhere. He had worked hard in Melbourne in a variety of dead-end jobs, but had nothing to show for it but a hard-won reputation for dedication. Pats on the back don’t pay the mortgage.

In his last job, he’d worked six days a week for a second-hand car parts firm in a southern bayside suburb. Yet he still lived with his elderly mother, lacking the money for a deposit on his own unit. His redundancy payment from Dulux, an earlier job, had long gone. Like many a lonely bachelor, he liked a drink, and found it hard to save money.

Now, aged forty-five, it seemed he finally had a break. In his kit was a signed, legally-binding, two-year contract to work in the mining industry at $60,000 a year, more than twice his wreckers’ yard wage back in Melbourne.

Even weeks afterwards, he must have marvelled at the good luck that had changed his life, when he’d spotted a small classified advertisement in the Herald Sun newspaper on 26 January, 1996.

It read: ‘GENERAL HAND GEO. SURVEY. Duties include camp maint. D/L essential. Suit single person 35-45 able to handle long periods in remote areas. Wage neg. Contract basis. Call 9423-8006 between 6-9 pm.’

He rang the number and found himself speaking to a Mr Jacobs, the man who would be handling the interviews. The nervous applicant slurred his words slightly but the prospective employer didn’t seem to notice – or didn’t care that the man on the end of the phone sounded a little drunk.

The prospective employer could afford to be selective. After all, fifty people had responded to the advertisement, but he was looking for a particular type, someone with special qualities. Ron Williams sounded most promising.

The first interview was held in modest surroundings – a small unit in the north-eastern Melbourne suburb of Greensborough, rather than a flash city office. That was easy to explain, and Jacobs explained it: he invested in WA exploration, not useless business status symbols.

For Williams the job sounded perfect – adventure, coupled with two years security and the chance to have another go at life, three thousand kilometres from past failures. Much better money, the possibility of being a key player in a small team, and the chance to work with an understanding boss who acted like an old mate. It sounded almost too good to be true.

Jacobs had sifted through the job applications looking for a man who was around his own age, had few ties and would not be missed if he disappeared. He short-listed fifteen names. Not a bad return from an ad that cost him $103.60 to run over three days.

Over the next few weeks Williams returned to the unit for follow-up interviews, each one bringing him closer to the job of a lifetime.

Slowly the form of the interviews changed and the questions became more personal. Williams found himself confiding in the man who could be his boss, telling him of his broken marriage, of childhood difficulties and of changing his name by deed poll fifteen years earlier.

This was new ground for Williams, who tended to be a loner and who tended not to speak freely of his personal life, even to workmates he had known for years.

But Jacobs was a good listener, and a sympathetic one, so the story of Ron Williams’s life came out, piece by piece. Finally, Jacobs told him he had passed muster. He had the job.

It was to cost him his life.

THE problem with Paul Jacobs was that he wasn’t. His real name was Alexander Robert MacDonald, a Vietnam veteran, bomber, prolific armed robber and escapee. He had escaped from the Borallon Correctional Centre, near Ipswich in Queensland, in September 1995. He had been serving twenty-three years for armed robbery and escape.

In the next two years MacDonald robbed seven banks in three states and got away with a total of $320,800. He was possibly Australia’s last bushranger. He robbed country banks, taking hostages to try to prevent bank staff from activating security alarms, and then he used his bush skills to camp out until police road blocks were removed days later.

MacDonald would hike hundreds of kilometres and drive thousands to rob banks in NSW, Queensland and Western Australia. While most modern bandits used high-powered stolen cars to get away from crime scenes, MacDonald used push bikes, small motorbikes or his hiking boots. He’d been out of jail only two months when he first developed a plan to take on a new identity. But, as the plan grew more sophisticated – and cold-blooded – he decided he needed a patsy. Someone whose life he could take over.

Which is how Ron Williams came by the worst lucky break of his life. MacDonald was only three months older than Williams and they had uncannily similar faces and builds, although the escaper was slightly taller.

Williams provided documentation such as driver’s licence, deed poll papers and birth certificate for his prospective boss.

MacDonald used them to set up two accounts, one in a bank and the second in a credit union, so he could channel his armed robbery funds. He went to the Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages to get a copy of the birth certificate he would later claim was his. He was to end up with a passport, driver’s licence, five credit cards, a Myer card, ambulance subscription and private health insurance under Ron Williams’s name.

But the trouble with taking someone’s identity is that there is a living, breathing witness who can expose the fraud at any time.

MacDonald believed he had that base covered. His credo was as old as crime: Dead men tell no tales.

It was brutally simple – and breathtakingly callous. So much so that Senior Detective Allan Birch, an armed robbery squad investigator, later had trouble grasping the ruthlessness of the quiet middle-aged man he was interviewing.

Puzzled about the identity swap, the detective said to MacDonald during an interview in on 26 July, 1997: ‘Can you explain to me how you would assume the identity of a person who responds to an advert for employment?’

MacDonald responded quietly: ‘You kill them.’

Birch: ‘Did you kill Mr Williams?’

MacDonald: ‘I did.’

RON Williams was a loner who spent most of his spare time fishing in Port Phillip Bay. He had married in July, 1981, and fathered a daughter but the marriage failed quickly. He legally changed his name from Runa Chomszczak to Ron Williams the same year he was married. He was a handyman who could make a fist of most trades.

He had plenty of workmates but few, if any, who ranked as true mates. He dreamed of adventure, but couldn’t see a way out of the rut his life had become.

He lived with his mother and spent as much time as he could at work, not because he was well paid or loved his job, but because it gave him company.

His former boss, the owner of Comeback Auto Wreckers, Kevin Brett, was to say of him: ‘He was a great little bloke. He was an all rounder. You name it, he could do it. He was a human dynamo.’

Brett said Williams was a gardener, handyman, storeman, painter and delivery man. He was a statewide reliever for Brett’s three car spare parts businesses.

‘He would have worked seven days a week if you let him. He lived for his work.’

He was later to die for it.

While Williams didn’t speak freely about his private life, his former employer sensed a sadness in his eager worker. ‘He was a little timid and easily let down. He’d had some knocks in his life.’

His only outside interest appeared to be fishing and restoring his car. Workmates said he would often head straight to the bay after knocking off work. He worked until the week before he was to go to Western Australia, but also kept a promise to paint the ceiling of a sandwich shop near his old job. That’s the sort of bloke he was.

Brett was happy to see his trusted handyman kick on to a new job, but he couldn’t help having a twinge of doubt – particularly when he found Williams had to sign a contract with secrecy provisions, and was being paid a retainer for weeks before he was to take up the new position.

His generous new benefactor was paying Williams around $500 a week not to work, which was more than he had been paid to work in Melbourne. It didn’t make sense to Kevin Brett, but he kept his doubts to himself, not wanting to dampen the enthusiasm of a man who, he felt, deserved a break.

Brett was to recall: ‘He was very secretive about his new job. I asked him about it and he said I had paid him peanuts and we had a laugh. He said the main reason he got the job was that he had no ties.

‘He said he took on the job because he wanted to get enough money to buy a unit. I told him there would always be a job here for him.’

His former boss said Williams would never have suspected he was being set up. ‘He just wanted to believe in people.’

THE new hand asked surprisingly few questions about the work he would be expected to do in the outback. ‘Mr Jacobs’ told him the business was ‘a family concern doing geological survey on order from mining companies in Western Australia.’

He asked Williams to sign an employment contract saying he would not seek, or take any other type of work before they travelled west.

When Senior Detective Birch asked him later, ‘Why did you do that?’ MacDonald was to answer: ‘That was purely and simply because the guy was a little unstable and really didn’t seem fully committed to the new employment, and I wanted to have him locked in to the program.’

They left for Western Australia in MacDonald’s Toyota Land Cruiser utility in late February, a month after the job was advertised. Williams packed light. The boss already had any provisions they would need. Like any seasoned camper, he had a shovel in the back.

They drove across the country for four days, staying at motels, and drinking and eating together. Both men were excited. Both were looking forward to starting a new life.

Williams wrote postcards to his old workmates, relatives and his few friends. His new boss and mate was his usual helpful self and said not to worry about mailing them. He promised he would do that later.

But one postcard was sent straight after it was written, when the two men arrived in Albany, about four hundred kilometres from Perth. Williams couldn’t resist a little good-natured gloating to his former workmates at the car wreckers in Melbourne. He sat down and wrote a card in a pub. It read: ‘Hello boss. I’m sitting with the new boss eating oysters kilpatrick. Got to go, new boss is bringing the beer over.’

The condemned man ate a hearty meal. His last.

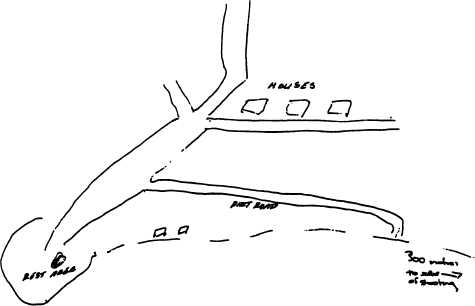

Shortly after they left Albany, MacDonald turned the dusty four wheel drive on to a dirt track leading to Cheyne Beach. He suggested they go fishing, knowing Williams was certain to be keen.

He had selected the beach by looking at a map because it was isolated. He remembered the district from his last visit, twenty years earlier.

They walked down to the beach from the utility, Williams carrying his fishing rod, MacDonald a khaki knapsack he’d bought in an army disposal store in Mebourne.

Williams fished and the two men chatted for about an hour. Both were waiting for sunset. Williams because he hoped it would make the fish easier to catch. MacDonald because he wanted to catch his prey unawares in the twilight.

As they chatted, MacDonald bent over slowly, undid the knapsack and slipped his hand in. Inside was the ten-shot, sawn-off, semi-automatic .22 that he had tested months earlier by firing into the Mary River, near Gympie in Queensland. He lifted the gun out and, as he was to describe it later, brought it to his shoulder in one smooth motion and fired. He was about a metre away. The last thing Ron Williams saw was the flash leaping from the barrel as the bullet hit him between the eyes.

‘He was just standing there … I shot him once in the forehead and again in the back of the head when he fell to the ground,’ MacDonald was to tell police, as dispassionately as if he was talking about slaughtering a sheep.

Senior Detective Birch asked him: ‘With what intention, if any, did you take Mr Williams to that location?’

MacDonald: ‘Of killing him … I stopped the motor vehicle, we took some fishing tackle from the rear of the vehicle, proceeded along the beach, fished for perhaps an hour and then I shot him.’

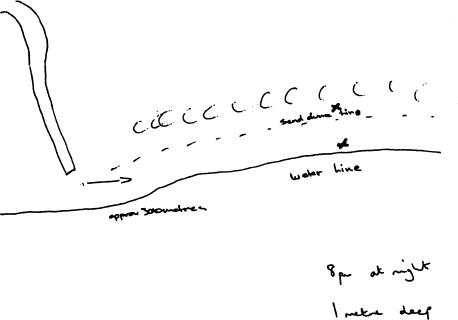

MacDonald said he checked Williams’ pulse to make sure he was dead, carried him thirty metres up a sand dune and buried him. ‘I dug a hole, placed the body in it, covered it with sand, smoothed out the area (and) put branches and shrubbery over it.’

Senior Detective Michael Grainger: ‘You say your intention was to kill him – were you apprehensive or were you just – you – you had a job at hand and you were doing that job?’

MacDonald: ‘It was a job at hand.’

He said that as he prepared to shoot he ‘just switched off, I guess.’

Birch: ‘What do you mean by that?’

MacDonald: ‘When you cut off your emotions … I guess it’s part of military training that sometimes you need to switch off your emotions … To be able to perform anything that needs to be done.’

It took him two hours to murder his travelling mate, bury his body and clean the area of clues. He left Cheyne Beach at 10pm.

Grainger: ‘Why – why did you kill him – what’s your reason for murdering Mr Williams?’

MacDonald: ‘To assume his identity.’

He was asked by police if he had any mental illnesses and he said he had been diagnosed with a personality disorder.

MacDonald: ‘Perhaps I don’t share the same emotions that other people do.’

Grainger: ‘Do you know that killing someone’s wrong?’

MacDonald: ‘I know that many people consider it to be, yes.’

Grainger: ‘Did you consider the killing of Ron Williams wrong?’

MacDonald: ‘No.’

Grainger: ‘Why?’

MacDonald: ‘To me, it seemed appropriate.’

Birch: ‘Have you found yourself in other circumstances where you’ve found it necessary to kill someone?’

MacDonald: ‘Yes.’

Birch: ‘When?’

MacDonald: ‘In Vietnam.’

But that interview came later. What he did when he left Cheyne Beach was dump his car, throw the number plates into a river, hitchhike back to Melbourne. He’d also discarded two identities, Paul Jacobs and Alexander MacDonald. But he kept the postcards Williams had trusted him to post. And post them he did, gradually, over several months. No-one who got the postcards could know that the return address scrawled on the back didn’t exist, any more than the man who’d written them. But his name did. The Vietnam veteran, bank robber and killer had become Ron Williams.

ALEXANDER Robert MacDonald was a Queenslander. The first time he saw the inside of a police cell was when he appeared at the Brisbane Magistrates’ Court on 1 December, 1967, charged with theft. He was fined $100 and given a two-year suspended sentence.

Perhaps it was suggested that military discipline might help him from returning before the courts because a month later he joined the army, entering the Recruit Training Battalion. In April, 1968, he transferred to the Artillery School in Manly, NSW, to train as a gunner. He had two tours of duty in Vietnam, the second at his own request.

Much later, he was described as having been a commando in the Special Air Services. This was untrue. But police believe he may have learnt about explosives in Vietnam when he was involved in jungle clearances, and he would have become familiar with firearms.

In 1972 he was charged with ‘unlawfully killing cattle’, fined $50 and ordered to pay $80 restitution at the Caboolture Magistrates’ Court in Queensland.

In October that year he literally walked away from the army, going absent without leave from his base. He never returned, and was discharged a year later under a rule for long-term absentees.

Ten years later he would write to the army and ask for his service medals for his two tours of duty. He was told he was not entitled to the medals as he had gone absent without leave.

In March, 1978, the licensee of the Crown Hotel in Collie, Western Australia, found a plastic lunch box at the rear of the hotel with a note addressed to him. It said the box contained a gelignite bomb that had not been primed. It was a warning.

MacDonald demanded $5000 from each hotelier in the district and threatened to bomb their pubs if they didn’t pay. He kept his word. Three months later a bomb exploded at the Crown, badly damaging the hotel, and it was only luck that stopped MacDonald being a cop-killer. A local policeman handled and examined the gelignite package only two minutes before it exploded.

MacDonald was arrested after he made an extortion demand for $60,000 from the hotels. He had built a bomb with four sticks of gelignite and had another sixteen sticks hidden in the bush. Police had no doubt he would have continued blowing up pubs until he was paid his extortion money.

He was sentenced to seven years over the bombings and extortion but served far less. He was released in September, 1981, and headed to Queensland.

Thirteen months later MacDonald was again a wanted man. Police said that between November 1982 and March 1983 he robbed several banks and service stations in central and northern Queensland.

It was during this time that MacDonald began to take hostages during robberies. In three bank robberies he took a staff member with him to ensure the police were not immediately called.

On 11 February, 1983, he robbed the National Australia bank at Mossman of almost $10,000. He took a staff member to the edge of a cane fields nearly five hundred metres from the bank and then vanished into the cane on foot.

Police believe he used a CB radio to contact his partner to pick him up.

In July, 1983, MacDonald was arrested in the Northern Territory as he was about to return to Perth. Again, the former soldier showed his extraordinary single mindness. On 28 July he escaped from the Berrimah Jail while awaiting extradition. In the escape he broke his ankle but still managed to travel four painful kilometres. He was forced to surrender after twelve hours on the hop.

He was sentenced to seventeen years jail. In 1984 he was given another six months for attempting to escape from Townsville’s Stuart Prison. Not to be deterred he tried to escape again, this time bashing a prison officer and trying to take a female nurse hostage.

He was given another five years for his efforts.

He had served twelve of his twenty-three year sentence for eight armed robberies, two charges of conspiracy to commit armed robbery, four counts of unlawful imprisonment and the attempted escapes, when he decided he’d been in jail long enough. This time his escape was successful.

Despite the fact he was serving a long sentence for crimes of violence and had tried to escape repeatedly he was given a position of trust. At the Borallon Correctional Centre, near Ipswich, he was allowed outside on gardening duty. On 12 September, 1995, he simply walked off. ‘I guess I couldn’t see the end of it,’ he later told police. He had three years to serve until he would have been eligible for parole.

He said he walked away and ‘skirted the general Brisbane area.’

Birch: ‘So how far would you have walked on foot?’

MacDonald: ‘Over a period of a week, a couple of hundred k’s I guess.’

He said he camped in the bush near Gympie for about three weeks after the escape.

On 20 October, 1995, he robbed the Westpac Bank in the Queensland town of Cooroy, near Noosa Heads. Then he escaped on a pushbike.

He went into the bank carrying his ten-shot .22 semi-automatic rifle. He said he selected the bank because it was near scrub where he could disappear.

He rang the manager earlier that day to make an appointment. Six staff members were in the bank. He was politely ushered into the manager’s office, where he produced the gun and demanded money. He was given $15,000, stuffed it into a travel bag and walked out. ‘I got on the pushbike and rode off along some back roads into the scrub.’

He camped out for two nights to beat the police road blocks. He used the money to set himself up with camping gear that he planned to use for more robberies.

He then robbed the Westpac bank at Airlie Beach on 15 December, 1995. ‘While I was in prison in Stuart Creek, a chap there had told me how he robbed the bank in Airlie Beach.’

He got there by walking and hitchhiking and then camped in the scrub. He needed only to glance at the bank the day before to know his prison mate had been right. It was an easy target.

Next day he went into the bank and said he had a complaint about an account. Then he produced the gun and demanded money. He walked out with $83,000 and a female teller as hostage. After they’d walked about 80 metres he let the frightened woman go, then walked into the bush.

After murdering Ron Williams he was to use the same method to commit five more bank robberies in Yepoon, in Queensland, Airlie Beach (again), Laurieton and Coonbarabran in NSW and Busselton in Western Australia.

Unlike most bandits he made little effort to hide his identity. He didn’t use the usual armed robber’s disguise of a balaclava or rubber mask. He wore a white Panama hat, almost as an identifiable trade mark, until he lost it during one robbery when he was chased into the bush.

He was a disciplined, cool, loner who went to great pains to cover his tracks. He lived quietly in Victoria as Ron Williams and would never pull a robbery there, instead travelling big distances interstate to pull bank jobs. He wanted police to believe that one of Australia’s most wanted men was half-hermit, living in a tropical rain forest, coming out only to rob banks. No-one, he believed, would look near Melbourne for the Queensland bushranger.

He even had a fresh tattoo, a parrot with the name Megan, put on his left arm, covering an older tattoo that was recorded on his police record.

He was asked by Senior Detective Allan Birch why he travelled out of Victoria to rob banks. ‘You could drive to Tocumwal or to Geelong. Why is it that you went north?’ the policeman said.

MacDonald answered matter-of-factly: ‘Well, to hopefully convince the police in Queensland that I was still in that area.’

Bizarrely, MacDonald was to come within metres of creating a huge international incident during an attempt to rob a bank at a tropical beach resort.

He took four days to drive from Melbourne to Cairns in his four wheel drive, and then took a bus along the winding coast road, past crocodile farms, caravan parks and five-star resorts to Port Douglas, later to become a popular holiday destination for American presidents, publishers and journalists. He took with him a second-hand black mountain bike he’d bought for $100 at the Cairns Cash Converters, and his dismantled double-barrel shotgun in his knapsack.

For a week he camped near the beach and walked around town. Like any other tourist, he wandered down the main street, past pubs, cafes and the prestigious Nautilus open air restaurant favoured by Bill and Hillary Clinton in happier times. But, unlike most tourists, he kept his eye on the Commonwealth Bank branch in the centre of the town.

He noted staff movements and saw that one man always arrived at the same time and parked his white Falcon in an underground car park, before walking a few metres to the bank.

He decided to abduct the staff member and demand that cash be delivered to him.

On Friday, 30 May, as the young staff member walked out of the carpark, MacDonald strolled over and grabbed him. He walked quietly with the man to the bank and then slipped a note to a female teller. It demanded that all the money in the bank be delivered to a spot on the banks of a river, about eight kilometres from Port Douglas, in exchange for the staff member’s life.

The gunman and the hostage drove to the river to wait near a disused bridge next to the highway. It was a popular fishing spot but MacDonald knew it was low tide and the area should be empty. But a fisherman, who obviously could not read a tide chart, wandered up to the robber and his nervous hostage as they waited.

‘A chap who had been fishing in the river came along and I had to take him in tow, so to speak,’ MacDonald was to tell police.

The three waited about near the road. MacDonald knew there was only a few police at Port Douglas and he could slip into the cane fields or rainforest if they began a search.

But his plan unravelled when he spotted a huge contingent of police on the main road. When he saw four marked police cars, motor bikes and unmarked units he believed he was in big trouble. ‘It didn’t pan out the way I figured it would.’

What he didn’t know until much later was that it was Murphy’s Law at work. MacDonald had done his homework on the bank – but he hadn’t read the local papers. The Chinese Vice Premier, Zhu Rongji, was in town after a tour around Australia.

Mr Zhu was heading for the Cairns airport with his massive police escort when he passed over the bridge near where MacDonald was hiding.

No-one knew that a killer with a loaded gun got within metres of one of the leaders of the biggest country in the world. But the killer didn’t know either. He thought that half the Queensland police force was about to descend on him, so he let the two men go and pedalled his second-hand bike about three kilometres, in one of the slowest getaways on record, then disappeared into the bush once more. He then walked more than forty kilometres back to Cairns, collected his car and drove to Airlie beach to rob the Westpac branch a second time. It was a long way to come from Victoria, and he wasn’t going to go home empty handed.

On 2 June, 1996, he turned up at a Somerville boat yard, Yaringa Boat Sales, saying he wanted to buy an old timber cabin cruiser that had been advertised in a boat magazine for $23,000. He didn’t seem too worried about the price. He would have been churlish to quibble. Three weeks earlier, on 10 May, he’d robbed the Yepoon Commonwealth Bank of $107,000.

He produced a $500 deposit to settle the deal on the cabin cruiser.

He returned ten days later with a briefcase. He opened it and took out $10,000 in cash. Three days later he was back with the same briefcase and another $12,500.

He was going through a messy divorce, he explained, and didn’t want his ex-wife to know about the money. So he carried it in the briefcase. It seemed reasonable to the salesmen.

He was to spend $80,000 on the boat, Sea Venture, fitting satellite navigation gear and reconditioned motors.

He paid $1200 cash to moor the boat at Yaringa and began to live on board. He told locals he was a builder and renovator who dabbled in prospecting.

He began to drink at the Somerville Hotel and developed a group of mates. At least six times he disappeared for up to eight weeks at a time. He told his new friends he was prospecting in Queensland. Which, in a way, he was. But not with a pick and shovel.

Just before Christmas, 1996, he threw a huge party for his friends, supplying all the food and liquor to celebrate completing the main work on the boat. During the refit a worker opened a waterproof case in the boat. Inside he found a sawn-off shotgun. He decided, perhaps wisely, not to ask questions.

In June, 1997, MacDonald told his friends he was short of cash and needed $10,000 before he could finish the boat and sail to the Solomon Islands where, he said, he was going to hook up with a friend.

He said he would head north on 27 June. Police believe he was going back to Queensland for one more armed robbery before sailing out of Australia to freedom.

He loaded up his Toyota with camping gear and provisions, then drove to the Hume Motor Inn in Fawkner and booked in to room eight.

While he was preparing to head north the television program, Australia’s Most Wanted, screened a segment on the escapee-bandit. Police received a call to look for a Toyota Four wheel drive in Melbourne’s north. Within hours they found the car, registered to Ron Williams. A police check confirmed that a Mr Ron Williams was a reported missing person.

A detective walked into the restaurant where MacDonald was sitting and immediately knew he was the wanted man. He was arrested by members of the Melbourne armed robbery squad outside the motel at 5.15pm on Thursday, 26 June, with his brother. He was extradited to Perth, pleaded guilty of murder and sentenced to life in prison.

When police went through his papers they found documents from the Christian Children’s Fund. Here was an armed robber who could kill a harmless stranger and steal his identity without a moment’s guilt, and yet sponsor a poverty-stricken child in South America.

RECORD of interview between Senior Detective Allan Birch and Ronald Joseph Williams, of Ford Road, Shepparton, conducted in the offices of the armed robbery squad on Thursday, 26 June, 1997. There is a long discussion where the suspect refuses to agree to be fingerprinted until it is explained that the prints can be taken by force.

BIRCH: ‘I suspect you of armed robbery and escape. In simple terms, Mr Williams – I believe you are actually Alexander MacDonald. I have information that Alexander MacDonald is responsible for the commission of a number of armed robberies and has escaped a prison in the state of Queensland.’

Birch then informs the suspect that police have the legal authority to take fingerprints forcibly.

BIRCH: ‘If you don’t comply or you don’t want to comply with that request, then I’ll seek authorisation from my superior to take them forcefully from you. All right?’

MacDONALD: ‘And who would that superior be? The man who assaulted me earlier?’

BIRCH: ‘Well, I don’t know what you are talking about.’

MacDONALD: ‘The gentleman who was here earlier on with you.’

SENIOR DETECTIVE MICHAEL GRAINGER: ‘What I suggest we do at this stage, Mr Williams, is that we suspend the interview.’

(After long discussions, MacDonald agrees to be fingerprinted.)

MacDONALD: ‘Well, it would seem that I have no option.’

(After the fingerprints are taken MacDonald knows it is useless to continue the charade of pretending to be Ronald Williams.)

BIRCH: ‘Can you please state to me your full name and address?’

MacDONALD: ‘Alexander Robert MacDonald, no fixed place of abode.’

BIRCH: ‘Right. Mr MacDonald, how did you come to be here in the office of the armed robbery squad?

MacDONALD: ‘I was apprehended, shall we say, on Sydney Road at Fawkner.’

BIRCH: ‘Where have you been residing for the last, say – six months?’

MacDONALD: ‘I live on and off in the Millewa State Forest.’

BIRCH: ‘And whereabouts is that situated?’

MacDONALD: ‘It’s near Tocumwal in New South Wales.’

BIRCH: ‘Right, and you live in the forest?’

MacDONALD: ‘I use tents and tarpaulins.’

Police asked MacDonald why how he came to be known as Williams.

MacDONALD: ‘Well, it’s an identity I’ve assumed since being an escapee.’

BIRCH: ‘Right. Now how did you assume that identity?’

MacDONALD: ‘By taking identity from the actual person.’

BIRCH: ‘Right. Who is Ron Williams?’

MacDONALD: ‘He’s a guy from Melbourne.’

BIRCH: ‘Right, do you know Ron Williams?’

MacDONALD: ‘Yes.’

BIRCH: ‘How do you know Ron Williams?’

MacDONALD: ‘I met him on the pretext of employing him.’

BIRCH: ‘Under what circumstances did you meet him?’

MacDONALD: ‘I needed an identity. I ran an advertisement in a newspaper … the Herald Sun … For someone to take up a position with a geological survey.’

BIRCH: ‘And what was the intention at the time of placing the advert?’

MacDONALD: ‘My intention was to find a person of suitable age, background. No – no close relatives, and assume his identity.’

BIRCH: ‘Right. How many persons responded to that, to that advert?’

MacDONALD: ‘Fifty, I guess.’

BIRCH: ‘Over what period of time did those fifty people respond?’

MacDONALD: ‘Within the space of – yes – a week.’

BIRCH: ‘Can you explain to me how you would assume the identity of a person who responds to an advert for employment?’

MacDONALD: ‘You kill them.’

BIRCH: ‘Did you kill Mr Williams?’

MacDONALD: ‘I did.’

BIRCH: ‘Can you approximate for me when that occurred?’

MacDONALD: ‘Early March, 1996.’

BIRCH: ‘Right, and how did you kill Mr Williams?’

MacDONALD: ‘I shot him.’

BIRCH: ‘And what were the circumstances … ?’

MacDONALD: ‘I required his identity. I transported him to Western Australia. Took him to a beach, and shot him there.’

MacDonald then explained how he put an advertisement in the paper, under the name Paul Jacobs, for a field hand for ‘geological survey work,’ and how he had formed a short list of men ‘with no dependents, no close relatives.’

MacDONALD: ‘He (Williams) was quite drunk at the time (when he rang) which was one of the factors that decided me to interview him further. A few days later Mr Williams turned up at the flat for the interview and looked even more promising.’

MacDONALD: ‘(He was) a guy of my build, roughly – maybe a little shorter. Obviously of the same age group.’ The prospective employee and employer had chatted for about an hour in the flat.

BIRCH: ‘When did you form the opinion that he was a person of whom you wanted to assume his identity.’

MacDONALD: ‘At that time I was about eighty per cent certain that he was suitable, so I asked him back for a second interview … at which he could supply more personal details … educational background, family background, employment.’

BIRCH: ‘Was that – in what way was that necessary to you?’

MacDONALD: ‘To give me the background story of that person.’

About six other men had telephoned for interviews but MacDonald put them off. At his second interview Williams said he had been brought up in orphanages, had no close family ties and had changed his name from Chomszczak. MacDonald had diligently written down all these personal details.

MacDONALD: ‘Yes, he was married to Margaret Joy Manning in 1981, July 1981.’

BIRCH: ‘And where is Mrs Manning now?’

MacDONALD: ‘He didn’t know … they divorced in 1982.’

BIRCH: ‘At the times you were writing down (the personal details) what was your intention with Mr Williams?’

MacDONALD: ‘To kill him.’ MacDonald then described how he had congratulated Williams, telling him he was the successful candidate, that he would be employed in WA for two years, and would be paid $60,000 a year if he signed a contract that he would not take up alternative employment. Until then, he had promised him a retainer of $500 a week ‘to lock him into the program.’ He then spoke freely to police about the murder.

MacDONALD: ‘It took place on Cheyne Beach in Western Australia at approximately 8pm. I shot him once in the forehead and again in the back of the head when he fell to the ground.’

BIRCH: ‘With what intention, if any, did you take Mr Williams to that location?’

MacDONALD: ‘Of killing him … I stopped the motor vehicle, we took some fishing tackle from the rear of the vehicle, proceeded along the beach, fished for perhaps and hour and then I shot him.’

BIRCH: ‘Right, where was the firearm?’

MacDONALD: ‘It was in a fishing bag that I had with me.’ (a khaki knapsack from a Greensborough army surplus store).

Senior Detective GRAINGER: ‘You say your intention was to kill him – were you apprehensive or were you just – you – you had a job at hand and you were doing that job?’

MacDONALD: ‘I had a job at hand.’

He explained he had previously tested the gun at a bush camp on the Mary River, near Gympie in Queensland.

He said he and Williams arrived at the spot and fished several areas along the beach before he committed the murder.

BIRCH: ‘What was he doing?’

MacDONALD: ‘I believe he was just standing there. We were talking about something or other.’

GRAINGER: ‘So how was it that you were able to distinguish him and kill him in the dark?’

MacDonald: ‘I have reasonably good night vision.’

He said that he had been a gunner in the regular army, serving for five years from 1968, and trained to use machine guns, rifles and grenade launchers.

MacDONALD: ‘I dug a hole, placed the body in it, covered it with sand, smoothed out the area put branches and shrubbery over it.’

BIRCH: ‘What were your duties to perform, or that you performed, in Vietnam?

MacDONALD: ‘I’d rather not go into that.’

BIRCH: ‘Did you cause a death of any persons in Vietnam, by way of shooting them with a rifle?’

MacDONALD: ‘I’d rather not discuss that.’

GRAINGER: ‘Prior to the actual killing of Mr Williams, when was it that you decided, right – this is the spot – this is where it’s gonna happen?’

MacDONALD: ‘When I first saw the area.’

GRAINGER: ‘And how long was that before you actually killed him?’

MacDONALD: ‘An hour and a half.’

He said that as he prepared to shoot Mr Williams he ‘just switched off, I guess.’

BIRCH: ‘What do you mean by that?’

MacDONALD: ‘When you cut off your emotions … I guess it’s part of military training that sometimes you need to switch off your emotions … To be able to perform anything that needs to be done.’

GRAINGER: ‘Why is it that you – you’re telling us all this? Do you have any reason for that?’

MacDONALD: ‘Well. It’s a foregone conclusion that you would’ve found this all out anyway.’

GRAINGER: ‘Why – why did you kill him – what’s your reason for murdering Mr Williams?’

MacDONALD: ‘To assume his identity.’ He was asked by police if he had any mental illnesses and he said he had been diagnosed with a personality disorder.

MacDONALD: ‘Perhaps I don’t share the same emotions that other people do.’

GRAINGER: ‘Do you know that killing someone’s wrong?’

MacDONALD: ‘I know that many people consider it to be, yes.’

GRAINGER: ‘Did you consider the killing of Ron Williams wrong?’

MacDONALD: ‘No.’

GRAINGER: ‘Why?’

MacDONALD: ‘To me, it seemed appropriate.’

BIRCH: ‘Have you found yourself in other circumstances where you’ve found it necessary to kill someone?’

MacDONALD: ‘Yes.’

BIRCH: ‘When?’

MacDONALD: ‘In Vietnam.’

MacDONALD: (Coughs) ‘Pardon me.’

BIRCH: ‘You okay. Got a bit of a dry throat?’

MacDONALD: ‘I think it’s the blasted cigarettes, actually.’

BIRCH: ‘They’ll kill you, they say.’

MacDONALD: ‘So they say.’

He then explained buying the boat to sail to the Solomon Islands.

GRAINGER: ‘Would that be in an endeavour to flee Australia?’

MacDONALD: ‘I don’t know quite how to phrase this. A terminal effort, shall we say.’

GRAINGER: ‘You intended to kill yourself in the Solomon Islands?’

MacDONALD: ‘That’s correct.’

GRAINGER: ‘Why is that?’

MacDONALD: ‘Because I didn’t see any future.’

GRAINGER: ‘Why would it be necessary to kill yourself in the Solomon Islands?’

MacDONALD: ‘More pleasant surroundings.’

The map that Alexander MacDonald drew to show police where he had buried Ron Williams’ body.