APPEARANCES can be deceptive. So can crooks. As Alphonse John Gangitano strutted along Bourke Street, central Melbourne, in the warmth of an early January evening in 1998 he looked nothing like a heavy crime figure whose power base was spinning into terminal decline.

Strolling along in the twilight with his loyal friend, bail justice Ms Rowena Allsop, his driver, ‘Santo’, and a solicitor who was part of his expensive defence team, Gangitano showed no sign of being nervous about fronting court next morning.

He was, after twenty years in and around the underworld, no stranger to the criminal justice system. He did not have to ask where the accused was expected to sit when he entered a Magistrates’, County or Supreme Court.

Gangitano was ‘quite jovial’ Ms Allsop was to recall of that evening on 15 January. ‘We went past a bookshop and he bought me a book on Oscar Wilde,’ she was to remember of the criminal she described as ‘a very special friend.’

‘We both had an interest in Wilde. We laughed at the quote, “There is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about”.’

According to Ms Allsop, Gangitano was widely read and, for a Melbourne gangster of Italian origins, had picked three unlikely role models: John F. Kennedy, Napoleon and Wilde. It seemed he was attracted to – and secretly craved – fame and recognition.

The group met at a trendy eatery, Barfly’s restaurant, near Spring Street, and then Ms Allsop and Gangitano, dressed in fashionable jeans and a crisp white Versace overshirt, went for a wander, window-shopping in two bookshops.

Ms Allsop, well known in political circles, seemed not to be worried about being spotted with a suspected killer less than a hundred metres from Parliament House. After all, her relationship with Gangitano had been the subject of scrutiny – and disapproval – all the way to the office of the Attorney-General.

The two stopped when urged to come in for a drink at one of the bastions of conservative Melbourne, Florentino restaurant. Gangitano ordered a scotch and Ms Allsop, a teetotaller, had a coffee.

Gangitano, who was on a court-ordered 9pm curfew, lingered over his drink until around 8.45. Ms Allsop reminded him that he should head home. Gangitano smiled and said there wouldn’t be a problem if he bent the bail conditions by a few minutes. It wouldn’t be the first time. The bail justice was seemingly unconcerned about the minor breach of the rules. There was no need to nit-pick.

‘He kissed me on both cheeks and I wished him well for court the next day and then he left,’ she said later. ‘He didn’t seem worried.’ Santo met him at Barfly’s to take him home to Templestowe in a late-model blue Holden. Ms Allsop never saw him again.

The relationship between the bail justice and the gangster had long been the subject of interest in legal, political and criminal circles. Rowena Allsop had been popular with many detectives because of her enthusiasm and energy as a bail justice. She was always prepared to come out late at night for a court hearing when called by the serious crime squads. She was fond of publicity, and other bail justices grumbled about her high profile, but no-one doubted her availability and sincerity.

The former athlete and football umpire moved easily with the champagne set. Why then would a respected Order of Australia recipient and confidante of many police be seen in public on the arm of a notorious criminal? When she appeared with Gangitano at a kickboxing show in Melbourne and jumped into the ring to present a trophy, many old friends shook their heads. Of course, tastes in friends and entertainment can be peculiar: sitting not far away from the gangster and the bail justice was a well-known lawyer and merchant banker, once mooted as a future Liberal Prime Minister.

Ms Allsop had to endure criticism that, as a bail justice, she should not have befriended a man reputed to be one of the state’s biggest crime figures.

If she thought her friendship with Gangitano would not reflect on her legal role, the illusion was shattered when she glanced at a police notice-board at an inner city police station while on duty.

On it was a typed list of eleven independent people to be called to observe interviews with minors and disadvantaged suspects to ensure their rights were protected. Next to Ms Allsop’s name, scrawled in pen, was: ‘Do not use … roots Gangitano.’

Ms Allsop gave character evidence for Gangitano in 1996 that brought out into the open a relationship that some police had been questioning privately for nearly two years.

She told the Magistrates Court she had met Gangitano for coffee and late-night meals. ‘He sees me as a role model in the community,’ she told the court. ‘He asked if I would be a professional person he could call on from time to time.’

Rowena Allsop became an unpaid bail justice in 1989 and was used by the homicide and armed robbery squads more than any other. She had a reputation of being able to be trusted with confidential information. But when she began being seen with a police target many detectives had second thoughts. After Ms Allsop gave evidence for Gangitano, a senior CIB officer instructed squad chiefs that she was effectively banned.

According to Ms Allsop, she became the victim of a vicious rumour simply because she was an attractive, single woman who tried to help a man who asked for assistance.

She knows that when police questioned her ‘friendship’ with Gangitano, it was shorthand for alleging that she was sexually involved with him. ‘It was totally malicious, outrageous and without basis. I wonder if there would have been all the fuss if I was married with two children or I was a man,’ Ms Allsop, a divorcee, asked. ‘I know how the police rumour mill works. A lot of females, including some policewomen I know, have been victims of it over a number of years.’

Police first started to turn on Ms Allsop when she walked in one door at the Carlton police station as Gangitano arrived through the other. ‘We were having coffee in Lygon Street when my phone went, asking me to attend at the Carlton station. He had to go there to report on bail and I was going there so I drove him the one block to the police station.’

Amid the controversy, the Attorney-General, Mrs Jan Wade, confirmed she would review the relationship, the police association claimed the issue was of ‘grave concern’ and the Victorian Law Institute said those involved in the criminal justice system should have no outside association with police, lawyers or their clients. The institute failed to mention several celebrated cases of affairs between police and lawyers, including one consummated in the interview room of a crime squad.

‘I know I have done nothing wrong. But in the end people will believe what they want to believe,’ Ms Allsop said in her own defence. Many believed the worst. Whether her relationship with Gangitano was brave or stupid is a matter of conjecture – and some debate. But there is no doubt the Victorian of the Year recipient, director of Odyssey drug rehabilitation centre and a former teacher at Winlaton Youth Training Centre, was branded unreliable in police circles.

Eventually the Attorney-General released a code of conduct for Victoria’s bail justices. It was a thinly disguised swipe at Ms Allsop and her ongoing relationship with Gangitano, a relationship she refused to abandon.

‘He was always a perfect gentleman in my company,’ she said. ‘I know he was no angel but I believe he was trying to change.’

But, for Alphonse Gangitano, gossip about whether he was having an affair with a bail justice was the least of his problems.

FOR a man who liked to look and act like someone always in control, Gangitano was becoming increasingly reliant on others: he needed a lawyer because, for the previous four years, he had been facing a string of criminal charges and he needed a driver because he had lost his licence for refusing a breath test.

But what he needed most was friends, and powerful ones, in the underworld. Restaurant owners and waiters might have waved and smiled at ‘Phonse’, but the men who make life-and-death decisions about career criminals were showing less affection towards the big man with the vicious temper.

Some police believe Gangitano’s death certificate was signed, but the date left blank, when he murdered popular crime identity Gregory John Workman on 7 February, 1995.

According to police documents, Workman and Gangitano, after attending a wake at a Richmond hotel, went to an underworld party in Wando Grove, East St Kilda, to raise bail money for an armed robber.

Gangitano was drunk and, as was his form, looking for trouble. He tried to pick a fight with a gambling associate then, about 4am, he pulled a pistol on another man and had to be dragged away.

About 4.40am, a woman heard what she thought were fire crackers above the noise of the party. She later told police she went outside and saw Gangitano, holding a pistol, standing over Workman, who was lying on the ground, bleeding profusely.

Workman had been shot eight times with a .32 semi-automatic pistol. He died several hours later.

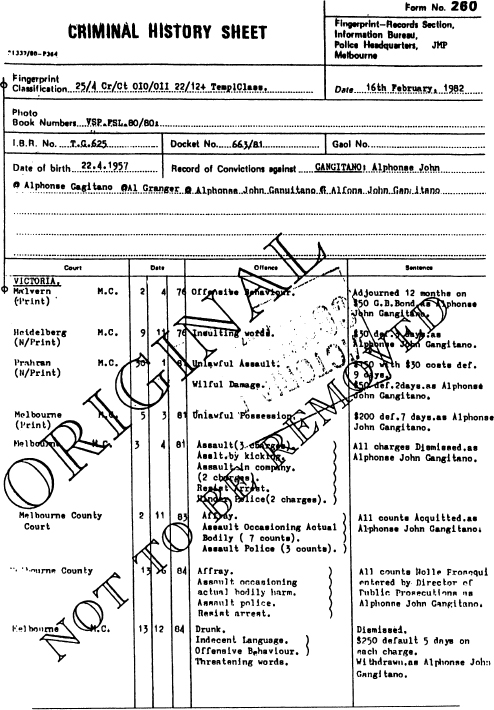

Two sisters made detailed statements implicating Gangitano and he was charged with the murder – the first serious charges levelled against him. For years police had wanted to nail him, but despite his growing reputation as a gangster his criminal record showed only minor offences.

Born on 24 March, 1957, Gangitano was the only son of a decent family involved in the travel and real estate businesses. An uninspiring student at De La Salle, Marcellin and Taylors College, he developed the reputation as a vain, arrogant bully who could be charming, but with a violent streak.

Fellow Marcellin student, Bill Birnbauer, who went on to become an award-winning journalist with The Age, recalled that Gangitano was a bash artist who used the king-hit with brutal results.

In April 1976, he appeared at the Malvern Magistrates’ Court charged with offensive behaviour and for the next five years drifted through the courts on a series of ‘kiddie crimes’ – vandalism and street offences. At that stage he was a hoon flexing his muscles, but in 1981 he was found with a firearm and over the next few years the young hood became steadily more violent. Backed by his gang, he developed a reputation for bashing police. He would see a young copper off duty at a disco and ask, ‘Are you in the job?’ When the young man nodded, Gangitano would lash out with a big punch without warning.

Over three years he was charged with hindering police, assault by kicking, assaulting police, resisting police and other crimes of violence. But each time the charges were thrown out and each time he would walk out of court a little bit cockier.

A confidential police special circular warned police of Gangitano and his team. ‘They approach members and assault them for no apparent reason. They are all extremely anti-police and are known to be ex-boxers. They often frequent in a group numbering approximately fifteen. They single out up to three off-duty police and assault them, generally by punching and kicking them. On most occasions in the past members have been hospitalised due to injuries received from these persons.’ Gangitano was described as ‘EXTREMELY VIOLENT AND DANGEROUS.’

In the early 1980s, Gangitano started to use his muscle and his mates to stand over nightclubs. He would arrive and tell owners that unless they paid protection money he would begin bashing patrons. More often than not the owners would pay for peace.

He also began to get a toe-hold in the booming illegal gambling scene, and had a slice of a profitable baccarat school in Lygon Street.

He was seen regularly at race tracks, owned racehorses and harness-horses, and was listed in police files as a suspected race-fixer in Victoria and Western Australia.

Police believed he sold guns from a nightclub in Brunswick. He began to associate with some well-known older criminals, including the man purported to be the best safe-breaker in Australia. He was graduating from hoon to hood.

In 1987, the ambitious young man went into partnership with an older Italian criminal in a scheme to open a casino in Fitzroy. It was to be a restaurant downstairs and a plush gaming venue upstairs. According to police records, Gangitano ploughed $300,000 of his own money into the plan. He didn’t know that police had set up a surveillance post across the road. The casino lasted just two days; police closed it down. It hurt the young thug’s pocket, but again he escaped prosecution. This became part of the Gangitano myth. Did he stay out of jail because he was paying off police, because he was cunning or just lucky?

The older he became, the more brazen he seemed. According to police, ‘good’ criminals try to hide their success. They know that the more they flaunt their wealth, the more likely they are to attract police and tax department interest. But Gangitano loved the spotlight. He would wander Lygon Street as if it were his kingdom and playing the role of a young Godfather, nodding to restaurateurs and chatting with fellow hoods.

Undeniably good looking, he dressed well and acted as nonchalantly as a man without a care in the world.

He became more closely involved in the boxing scene and had strong links with the camp of world champion Lester Ellis. Long-time boxing rival and fellow world champion Barry Michael was bashed and bitten by Gangitano and his associates at a King Street nightclub in 1987.

Gangitano was vicious, but also unpredictable. Once, a policeman was eating with a woman other than his wife in Lygon Street when he took offence at the bad language at a table behind him. He turned around and demanded they keep the language down. The off-duty detective only then realised he had confronted a group of thugs, including Gangitano.

The policeman fully expected the incident to become violent and was surprised to hear Gangitano castigate his team for their behaviour. The hoods left and the head waiter arrived with the most expensive bottle of wine on the menu. It was a gift from Alphonse, to apologise for his friends’ language.

The same man was known for bashing people for little or no reason. He shot a criminal in the knee at a family wake and was believed to be involved in several other shootings.

In the underworld, no-one is beyond intimidation and Alphonse could also be the prey as well as the hunter. His long-time enemy was Mark Brandon Read, the standover man who had his own ears cut off while in Pentridge Prison’s infamous H Division. In the late 1980s, Read took on Gangitano’s gang and demanded payment. The long-awaited confrontation was on the cards when Read walked into one of Gangitano’s haunts in Lygon Street.

The earless standover man was dressed well, but under his leather jacket was strapped several sticks of gelignite, equipped with a fuse. In his mouth was a lit cigar. The threat was too much. According to underworld legend, when Gangitano heard Read was waiting for him and prepared to blow the club sky-high, he slipped through iron security bars in the lavatories and ran away.

A group of criminals once planned to use land mines to kill Gangitano at his eastern suburbs house but abandoned the plan because of the likelihood of other people being killed.

When Read was due for release in 1991, after spending five years in jail for shooting a criminal and burning his house down, an associate of Gangitano’s went to H Division to try to strike a peace deal. But, at the same time, police knew that Gangitano’s people were offering a $30,000 contract on Read.

It might have been a coincidence, but Gangitano decided to leave Australia in July, 1991, around the time Read was due out of Pentridge.

He returned in January, 1993, weeks after Read was back in jail in Tasmania for shooting another criminal. Police phone taps showed that Gangitano had been in constant contact with his Australian criminal connections while in Europe. Read was later to claim he received regular four-figure payments from Gangitano to stay out of Victoria. Several taskforces from the Victoria Police, National Crime Authority and Federal Police worked on Gangitano, but had come up with nothing.

For a time it looked as if the man who loved to play the gangster was beyond policing. But when he opened fire on Greg Workman in St Kilda, the game changed. There were witnesses and there was a corpse.

For the police, this promised to be the big break.

Gangitano knew he was in big trouble and went straight to his legal team. A high-profile lawyer called the homicide squad: Would they like to interview his client about the demise of a Mr Workman? Homicide detectives said he could wait. They would conduct their inquiries and interview people when they decided. They wanted Gangitano to swing in the breeze while they gathered evidence.

They knew they would never get a confession, so they had to have a watertight case.

The key was the two sisters who witnessed the crime. Both identified Gangitano as the trigger man. One saw him led away from the dying man by another gangster. Others confirmed the argument at the party and others told lies. The case looked good, and the police moved in to charge the gangster.

But as they celebrated in anticipation of putting Gangitano away for twenty years, their case was already unravelling.

The sisters had been hidden away under witness protection. They should have been safe and beyond influence, but it all went wrong. Police documents described the women as ‘fearful for their safety and in an extremely fragile state’.

The women began to lose confidence in the police when, despite being promised protection, they were driven down Lygon Street and actually spent a few nights staying in the heart of Gangitano country, Carlton.

They complained that they were treated like criminals, refused wine with meals, not allowed to go to a hairdresser, and refused permission to buy food instead of living on takeaway fast food.

They were moved to Swan Hill, where they nearly ran into an associate of one of Gangitano’s best friends. Police moved them to Warrnambool and put them in a cabin at a caravan park. It was hardly five-star accommodation. Worse, they were left alone, and told there was a twenty-four-hour hotline they could ring if they needed help. Three times they rang and three times the phone rang out. Alone and frightened, they contacted a friend of Gangitano’s in a bid to make peace. Big Al’s friends jumped at the chance and organised the girls to be driven from Warrnambool to a Melbourne solicitor’s office.

While police believed their star witnesses were safely tucked away in country Victoria, on 6 March, 1995, both women were making taped statements in a lawyer’s office recanting their original police statements. It was not the police witness scheme’s finest hour.

The women were secretly driven back to Warrnambool. Two days later, police discovered their case was mortally damaged. On 20 May, the sisters flew from Melbourne to England and said they would refuse to testify in the murder case. It is believed Gangitano paid for the flights and all expenses for their extended ‘holiday’.

Police dropped the murder charges against Gangitano and were presented with a $69,975 legal bill by his defence team. Police negotiated and paid a reduced fee. By withdrawing the charges before a trial, police left themselves the opportunity to re-charge if their case improved.

Late in 1997, the sisters slipped back into Melbourne. The police had another go, quietly working to get them to make fresh statements so Gangitano could be charged again.

But Workman’s friends had little faith in justice being done through the legal system. According to police sources, several months after the murder, criminal associates of the dead man made contact with Gangitano’s offsiders and asked, ‘If we kill him, will it start a war?’

At that time, Alphonse still had enough friends to protect him but, in the following year, his power base eroded. His behaviour became more erratic. Stories surfaced of him fighting with old gaming associates, of money problems – and even rumours of a drug habit, which was proven wrong after his death, when a toxicology report showed no signs of drugs in his system.

He was alleged to have fallen out with three brothers who control a large segment of the Lygon Street ‘mafia’.

The opening of Crown Casino had dried up much of the illegal gaming industry that had been a milking cow for Gangitano and his friends. And while he had beaten the murder charge (at least temporarily), he was under legal siege. Although not facing heavy charges, he was subjected to a series of draining legal problems. Charges of assault, refusing a breath test and possession of a firearm began to bite.

He spent time in jail on some charges and was bailed on a night curfew on others. He couldn’t prowl his patch late at night and began to lose control. The illusion that he was above the law, that he had paid off the police and that he would never go to jail, was shattered.

The standover man was beginning to be stood over by the law. But even as his empire crumbled, Gangitano worried about his looks. When reporting for bail he noticed the police Polaroid picture on his file was less than flattering. He had a professional shot taken and brought it to the police station when he next had to report and had it exchanged for the harsh photo.

Even though still in Tasmania’s Risdon prison, Chopper Read knew what was likely to happen to his enemy. A month before Gangitano’s murder, Read predicted the Carlton criminal had been marked for death.

‘Al is not long for this world, I fear,’ Read confided from his cell.

Read said he was concerned that Gangitano’s enemies might wait for his own release from prison before killing the gangster.

‘I have heard that some would like to have me out so that I would be blamed for any misadventures that may befall the unfortunate Mr Gangitano,’ he said.

But, later, Read said Gangitano had only weeks to live. A television reporter wanted to organise an interview with Gangitano and Read when the latter was released from prison in February, 1998. ‘Not possible, darling,’ Read said. ‘He’ll be dead before I’m out, I’m afraid.’

Read, a crime author, had planned to dedicate his next book to Gangitano with the words, ‘To Al, get yourself a sense of humour’.

After the killing, Read said: ‘Alphonse was betrayed from within his own camp. There were plenty of crocodile tears at his funeral. Ultimately people like Alphonse are killed by their friends, not their enemies. His mistake was that he could no longer tell the difference.’

The fact that Read was in jail at the time of the murder did not discount him as a suspect. Detectives interviewed two of Read’s closest associates, ‘Dave the Jew’ and Amos Atkinson, in relation to the murder. ‘The Jew’ was purported to be an underworld killer and Atkinson had once held thirty people hostage in Melbourne’s Italian Waiters’ Club in a crazy attempt to free Read from jail.

Both men said they could not help police with their enquires. ‘The Jew’ denied he was at all violent, although police found an axe in his bedroom.

In September, 1997, crime commentator ‘Sly of the Underworld’ said on the breakfast program of radio station 3AW that a well-known Carlton gangster had fallen out with former allies and was likely to be murdered. Gangitano contacted ‘Sly’ through an intermediary and said it was nonsense. ‘We laughed about it,’ Gangitano said.

When police searched his house after he was killed, they found a transcript from the radio segment that predicted his murder.

Although Gangitano has been publicly identified as a heavy gangster, some police believe his reputation was bigger than the man.

But certainly he was probably the highest-profile criminal in Victoria in the 1990s, mostly due to his own efforts to make sure he was. All major criminals knew him. Gangitano, also known as ‘Al Granger’ and ‘Al Gange’, gave his occupation as property developer. Police claim his income came largely from drugs.

Aged forty, Gangitano was old for a standover man and he needed to graduate from thug to organiser, a move that seemed beyond him.

Still good-looking and fit, he wanted to be a part of the nightclub scene, as a patron, a standover man and an owner, although his court-ordered curfew made that impossible.

Gangitano was reputed to have a financial interest in several nightclubs in Melbourne and some entertainment spots in Carlton. The Liquor Licensing Commission banned him from having any involvement in one club because of his criminal background. He was alleged to have extorted money from fast-food vendors in the city nightclub belt.

When arrested by police after one assault, he yelled, ‘Do you know who I am?’ A police baton across the back of his legs answered the question.

‘He was dangerous, unpredictable and violent,’ said a policeman who watched him, ‘but he was well short of the elite.’

Many professional criminals were surprised at how Gangitano brought police and public attention to himself by indulging in glorified pub brawls and bashings while they were busy making serious money.

Gangitano was always security conscious, but almost no-one is immune from a professional hit, especially one performed ‘on the inside’. Police believe that many of Alphonse’s so-called friends knew he was about to die.

He was shot dead in his home after the first day of his committal. There was no sign of a struggle. It seemed that Gangitano welcomed his killer into his home. The fact he must have known his killer is little help to police, because he probably knew all Melbourne’s gunmen.

For police investigating the murder, it is not so much a case of trying to find enemies of the deceased, but of eliminating potential suspects from those known to have a grudge against him.

A man with a savage temper who is quick with his fists and a gun makes enemies. Many patient men in the underworld hold grudges for years, waiting until their target loses influence, and age dulls the survival instinct.

One policeman said of Gangitano: ‘He was not wealthy and good criminals dropped off him because he attracted trouble and police interest. The elite use crime to make money. Alphonse wanted to be seen as a crime boss, but at the end of the day he was just another thug with a bad temper.’