HE was Victoria’s longest-serving prisoner, yet in the eyes of the law he remained an innocent man. He was declared mentally ill, yet was repeatedly denied treatment in a psychiatric institution.

In August 1998 the forgotten man of the prison system, Derek Ernest Percy, was put under public scrutiny for the first time in twenty-nine years when his unique case was reviewed in the Supreme Court. It was the first time since 1969 that he’d been given the chance to argue why he should start his journey to freedom and why society no longer had a reason to fear him.

Hundreds of more notorious criminals have passed through Australian jails in the past three decades, and few people remember Percy. The police who arrested him have long since retired, his defence lawyer has moved on to be a respected Supreme Court judge, and many of the jails that had held him had since been closed. He was a model prisoner, seemingly content to play carpet bowls, collect stamps and browse though the cricket statistics he kept on his personal computer.

Yet many in the criminal justice system feared the day this seemingly harmless man would be given a legal opportunity to push for his release. On Derek Percy’s first day in a cell Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, John Gorton was Prime Minister, Australian troops were fighting in Vietnam and a bottle of milk, home delivered by the local milkie, cost 19c. Derek Percy was twenty-one.

Percy has been in prison since he was arrested for the murder of Yvonne Elizabeth Tuohy, a twelve-year-old girl he abducted, tortured, sexually assaulted and killed on a Westernport beach, near Melbourne, on 20 July, 1969.

On the fifth day of his Supreme Court trial in March 1970 he was found not guilty on the grounds of insanity and sentenced to an indefinite term at the Governor’s Pleasure.

Three psychiatrists gave evidence of his ‘acute psycho-sexual disorder.’ A jury found it impossible to believe that a sane man could have done what Percy did to young Yvonne Tuohy.

It was in the days when only the defence could raise the issue of the accused’s sanity and it was also in the days when capital punishment was still on the statute books.

Ronald Ryan was the last man hanged in Australia in 1967. Percy would have been a candidate for the noose if he had been found both sane and guilty.

The defence of insanity was usually raised only by the defence as the last throw of the dice in murder cases.

Grieving relatives of Yvonne Tuohy were assured on the steps of the court that Percy was so twisted he would never be released.

In the 1960s and 1970s the difference between being found not guilty on grounds of insanity by a criminal court rather than guilty was more an argument in semantics than of treatment. The terms ‘patient’ and ‘criminal’ amounted to much the same thing. No matter what the court found the sane and insane were taken by prison van and dumped in Pentridge.

But in the 1980s treatment improved and inmates who, in the eyes of the law were insane, were moved to psychiatric institutions. All, that is, except Percy.

Many were given long-term leave and were no longer seen as dangerous. In 1998 all forty-seven Governor’s Pleasure ‘clients’, were told their cases would be reviewed in the Supreme Court to see if they should be freed. One, James Henry Patrick Belsey, who had lived without incident in a Melbourne northern suburb, died only weeks before his case was to be heard. He had been diagnosed with inoperable throat cancer several months earlier.

Belsey stabbed and killed Senior Constable Charles Norman Curson on the steps of Flinders Street station on 8 January, 1974, but years later he became balanced enough to live quietly, spending his days helping the aged and infirm with their mundane chores.

The changes to the law have been seen by politicians, judges, police and psychiatrists as humane, progressive and just. The Mental Impairment and Unfitness to be Tried Act took decisions on Governor’s Pleasure cases away from politicians and into the hands of judges.

By the mid-1990s about half the Governor’s Pleasure clients lived in the community on extended leave and were no longer seen as a danger to anyone. The rest remained under the supervision of government psychiatrists with varying levels of security.

But, through it all, Percy was the exception. He stayed in jail and seventeen internal reviews all said he remained as dangerous as the day he was arrested.

GROWING up, Derek Percy was hardly in one area long enough to make friends, but he had always been so self-absorbed the moves did not seem to worry him — at least outwardly.

He was the oldest of four boys, one of whom died from diphtheria as an infant when Derek was ten. His father was an electrical mechanic and the family moved from Sydney to Victoria when Derek was eight.

Percy senior was employed by the SEC and was often moved from post to post around Victoria. In ten years, the family lived in Melbourne, Warrnambool, and in Victoria’s high country. Derek went to seven schools, was brighter than average, and wanted to be an architect.

He seemed a little cold and aloof, but that was put down to the shyness that came from living on the move. No teachers or schoolmates became close enough to him to consider him as anything but ordinary.

As a child he gravitated to solitary activities. He enjoyed stamps, building up a collection of more than ten thousand, and he inherited his father’s love of yachting, although he preferred to sail on his own. When he was arrested he owned a Moth-class yacht. He loved to read and, like many teenagers, he took to keeping a diary to record his innermost thoughts.

For Percy, the diary was probably more important than for most kids because with his family’s constant moving he didn’t have a close friend to confide in.

When he was seventeen his parents stumbled on his diary and began to read. What they saw left them horrified. Their quiet, intelligent oldest son was having bizarre sexual fantasies. Worse, many of the fantasies involved children.

His parents took him to the local, overworked doctor. According to a prison report written years later they were told not to worry as the writings were ‘just a stage of growing up.’

‘No other action was taken,’ the report said.

After Derek finished year eleven his father bought a service station near Newcastle, and the family moved again. The boy enrolled in his final year at Gosford High, but he gave up, tired of starting again at a new school.

His new plan was to get a job in a drafting office, but he soon found he was under-qualified, and started working with his father in the family service station for five months.

At nineteen, he decided to join the navy and was accepted within a week of lodging his application. For the next eighteen months he was stationed at three bases in Victoria and NSW. With an IQ of 122, he was offered the chance to complete officer’s training. The navy felt he had a future. He took orders well, was bright and loved the sea.

No-one knew that he was still keeping his diary, and far from ‘growing out’ of his sadistic sexual fantasies. They were getting worse.

YVONNE Tuohy was quite grown up and independent for a twelve-year-old. During the week she would play with kids from her school, but at weekends she would see the Melbourne families that came to Warneet to relax on the Westernport beaches.

Her parents owned the local shop and ran the boat hiring business, so they knew all the locals and regular holidaymakers by name.

Yvonne liked to explore with a young Melbourne boy, Shane Spiller, who came to Warneet with his parents most weekends. Apollo 11 was circling the moon when the pair asked their parents if they could go for a hike along a peaceful strip of a Westernport beach on a winter’s Sunday afternoon. It was 20 July, 1969, in an era when parents were not concerned by their children being out of sight. It was a fine day with enough sun around to encourage the children to get some fresh air and make their own fun.

Frank Spiller was up a ladder painting the side of the family’s weatherboard weekender when his son suggested a walk with Yvonne. The Spillers liked to leave Melbourne at the weekends to spend their time at Warneet, less than an hour from their eastern suburbs home. It was such a nice spot that years later Frank and his wife, Daphne, were to retire there.

Daphne Spiller cut sandwiches for the kids, and Shane grabbed his little tomahawk to cut wood for a billy tea on the beach.

The country girl and the city boy walked down a vehicle track, past a small car park to Ski Beach. Shane noticed a Datsun station wagon with a man sitting behind the wheel. ‘I had a feeling that day he was bad news,’ Shane Spiller was able to recall almost thirty years later.

In the car was Derek Percy, who had a weekend leave from Cerberus Navy Base. He had gone to the Frankston drive-in the previous night, slept in his car and driven to Cowes. On his way back he pulled into Warneet. For years, he was later to admit, he had been having dark thoughts about sexually molesting and killing children, but he was to claim he didn’t believe he would ever act on these impulses.

When the kids reached the beach they remained undecided for a few seconds whether to head to a friend’s farmhouse or to the nearby township. Confused, they walked in opposite directions for a few moments, then turned to walked back to each other. They were only metres apart when Percy appeared and grabbed Yvonne. The sailor produced a red-handled dagger and menaced the girl and ordered Shane to come to him, but the young boy pulled his hatchet from his belt and waved it above his head to keep the him away.

‘We were there for a long time while he was trying to entice me to him. I don’t know if it was minutes or seconds,’ he was to say of a scene that is burned into his memory.

Percy held the knife to Yvonne’s throat, forcing the young girl to try to beg her friend to give up. ‘Come back or he’ll cut my throat,’ she is alleged to have said.

Instead, Shane ran off through 200 metres of scrub to get help. As he neared the road he saw the attacker drive off with Yvonne in the car. He screamed, but a family having a picnic nearby ignored him, later telling police they thought the kids were just playing. One of the parents was later to approach young Shane to apologise. Three decades later, he still could not forgive them.

According to police, Shane Spiller’s actions saved his life and ultimately helped catch the killer. They say if he had not gone for help Percy would have killed him as well as Yvonne Tuohy. With no living witness, he may never have been apprehended.

Police said the youngster was an excellent witness who remembered details that led them to Percy. He described the killer’s car and sketched a sticker he had seen on the back window. It was the navy insignia.

BIG Jack Ford, then head of the homicide squad, and his team raced to nearby Cerberus Navy Base and found Percy washing blood from his clothes. They also found his diary. After reading chilling details of what he intended to do with children they were in no doubt they had their killer.

According to police this may have been a random attack — but it had been planned in the killer’s mind over the years. Again and again he would fantasise about abducting children and he would write in detail of how he planned to kill them. As the hours passed, Yvonne’s parents still hoped the crime would be abduction — even a rape — but not a murder. But when Ford returned to Warneet it was to bring the worst possible news. He walked up the path to the Spillers’ house where the Tuohys were huddled together, waiting. Frank Spiller was outside and asked if there was any hope. Ford shook his head and silently ran a finger across his own throat to indicate the child was dead.

Shane Spiller was a model witness. He gave the police the lead, then on the same night he walked through the navy base car park until he identified the killer’s station wagon. Later, at a police line up, he had to walk up and touch the man who had planned to kill him.

Nothing was too much trouble for the young boy. He posed with his tomahawk for press photographers and didn’t miss a court date, giving evidence bravely and honestly, even when he believed a relative of Percy continued to stare and intimidate him inside the court, trying to bully him into a mistake.

At the end of the ordeal grateful police had their sketch artist draw a picture of the boy and gave him a show bag of gifts as a thankyou. Then they then just moved on to the next case.

But Shane Spiller couldn’t move on. The bright, observant little boy didn’t recover. He was afraid of the dark. He was concerned that Percy would break out and come looking for him.

Family and friends believed that time would heal the wound. They were wrong. Time turned into an angry, festering sore.

He began drinking at fourteen, sought psychiatric help at eighteen. In an era before victim counselling Shane Spiller became increasingly bitter that no-one seemed to understand his pain, fear and loneliness.

Half a lifetime later his friends say, ‘He’s in a pretty bad way.’

In 1998 police found Spiller, who had tried to lose himself in country NSW, and told him that despite what had been promised, Derek Percy’s case was to be reviewed. The man who had stolen Shane Spiller’s chance of a normal life was going to be given the opportunity to salvage his.

‘It’s really knocked me around, mate. I still get nightmares. I spin out. I’m going through a rough trot now,’ Spiller was to say afterwards.

The news brought to the surface fears that were never truly hidden. But it also gave him the chance to talk about the ugly things that had festered inside him. Police finally put him in touch with counsellors. He was told that he was not weak, not strange, just a victim who, understandably, couldn’t cope.

‘I think about it every day of my life, mate. I’ve searched for help. I think I’m starting to get it now.’

He said he’d been good friends with Yvonne. ‘We couldn’t have been closer. She meant so much to me. I’ve never had a decent relationship since then.’ Shane Spiller lives on a disability pension, has been unable to hold down full-time work, and keeps a pick-handle next to his bed.

He admits to long-term battles with alcohol and drugs.

‘What happened stuffed me. I think I could have had quite a successful life if it wasn’t for that.’

He said for years he was frightened Percy would come after him. ‘In the line up at Russell Street (police station) I had to pick him. I had to walk up and point right at his nose. The look he gave me. I can still remember it.’

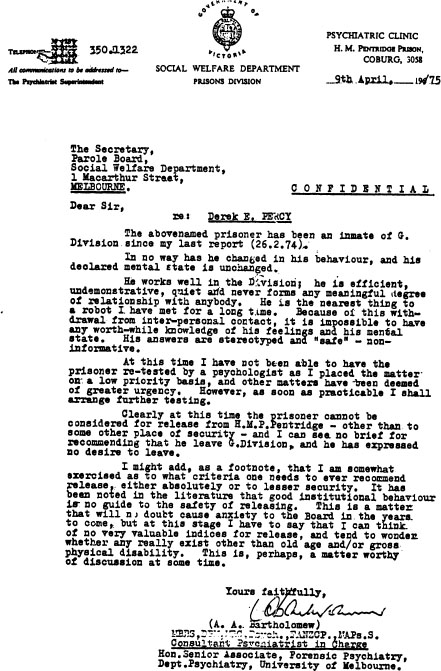

Five days after the killing Percy was interviewed by prison psychiatrist Dr Allen Bartholomew. ‘Bart’, as he was known in prison and police circles, had known most of Victoria’s maddest and baddest and he had seen the worst and the most bizarre the human condition could provide.

He was as close as you could get to being unshockable.

Percy told Dr Bartholomew he had been watching the two children when he was ‘overcome by a feeling — almost a compulsion — to do things to kids.’ He said that over the previous four years he had weekly fantasies of sexually molesting and killing children. ‘These thoughts worried him but he did nothing as he never thought he would be game enough to do it,’ the psychiatrist later wrote.

Dr Bartholomew had learnt through dealing with 1500 criminal cases that time was on his side. His experience was that if you sat back you could develop a relationship with even the worst offenders and, with patience, learn their inner secrets.

But not with Percy. His few comments five days after the crime were to be his most animated. No-one could have known the window into his dark psyche was already closing.

AFTER a year in jail Percy described himself as ‘a loner, not lonely’, but Dr Bartholomew still hoped that over time he would be able to learn more about the distant killer.

‘He demonstrates no behavioural evidence of any psychosis and his talk is rational — demonstrating reality-based thinking. He is rather retiring, having little to do with other prisoners, and only superficial relationships with the staff.

‘I am quite unable, at this stage, to offer any prognosis regarding the prisoner, but clearly he is a potential danger to the youthful community. At present one can only wait and observe, and later attempt to further investigate the prisoner. I hope that he may be allowed to remain in G Division for the next few years — he is a rare and interesting case.’

An experienced parole officer observed him in the early days and stated: ‘He is intelligent and his conversation follows a detailed, but matter of fact, cold format. He evidences no emotion and he describes his activities as if he was carving up a Sunday joint of meat.’

Most people who enter the jail system as adults without having been through the youth training system find it terrifying, but Percy adapted quickly, which was not surprising considering his lifelong capacity to withdraw into himself. ‘Prison is all right if you go along with it and do what you are told and it’s all right — like the navy,’ he was to say during a review.

He had reasons to remember the Navy fondly. After he was charged he received $1270 in back pay and a fortnightly pension cheque while in jail – making him one of the most affluent prisoners in the system.

Much later he was able to invest his pension fund in gold, build a bank account of almost $30,000, and buy a personal computer.

His interests included playing the guitar, making model boats he put in bottles, reading science fiction and maritime novels, and playing tennis. He was quiet and described by the chief of the division as ‘a model prisoner (who) consistently receives excellent reports for conduct and industry.’

It might have appeared that Percy was changing, but he wasn’t. A routine search of his cell on 28 September, 1971, showed that he was still writing down bizarre and sadistic thoughts.

Prison officers found detailed plans of what he wanted to do with children. They found pictures of children hidden in the cell. The brutal and graphic writings belied his passive exterior.

‘Thus at about September 1971 the prisoner was behaving in a manner very similar to the year or more prior to the killing with which he was charged: apparently normal behaviour to the ordinary onlooker but a grossly disturbed sexual fantasy life,’ Dr Bartholomew recorded.

As the years passed Dr Bartholomew and other psychiatrists started to doubt if they would ever break through the walls around Percy’s mind. In April, 1975, he wrote: ‘He is efficient, undemonstrative, quiet and never forms a relationship with anybody. Because of this withdrawal from inter-personal contact, it is impossible to have any worthwhile knowledge of his feelings and his mental state. His answers are stereotypes and safe — non informative.

‘I have to say that I can think of no valuable indices for release, and tend to wonder whether any really exist other than old age and or gross physical disability.’

The following year Dr Bartholomew described Percy as a ‘colourless and somewhat withdrawn individual. His behaviour is above reproach but what thoughts go on in his mind I have no idea. Any endeavour to become to some extent involved with him is repulsed. He must be seen as a danger to children.’

He would talk to Dr Bartholomew about matters such as Test Match cricket, but refused to open up about his personality.

‘I suspect, but cannot prove, that this prisoner has a rich (and morbid) fantasy sexual life but that he has learnt that it is to his own advantage that he covers it up. The prognosis is not good and I cannot see him being released for a long time yet,’ he wrote in 1977.

Professor Richard Ball, who gave evidence at the first trial, re-interviewed Percy in January 1977. ‘He volunteered nothing and extracting information was like pulling teeth.’

‘I doubt that he is entirely without sadist fantasies.’

In 1979 he revived his teenage hobby of stamp collecting and the following year he started tertiary computer studies. He had earlier started group therapy for sex offenders, but after nine months he drifted back into his own world.

He did not want to leave a protection division in Pentridge because he had been in jail long enough to know what happened to child killers in mainstream jail. Computer nerds who cut up kids were easy prey for real crooks.

By 1980 he could be seen wandering around his division with a screwdriver, trusted to do electrical work in the jail. In his eleventh year in jail his supervisor wrote: ‘One can’t help but feeling that there is, in fact, much under the surface that he chooses not to reveal.’

He was then moved to J Division in February 1981 and for the first time Dr Bartholomew was prepared to write what many had suspected for years: Percy had beaten the system. He was not mad and had never been so. ‘He is not formally psychiatrically ill, and is not in need of treatment at this time.’

Another psychiatrist, Pentridge Co-ordinator of Forensic Psychiatry Services, Doctor Stephens, wrote: ‘Percy is sexually grossly disturbed and should never be released from prison.’

In 1984 Percy told his mind minders he did not dwell about the killing of Yvonne Tuohy. ‘His memories of what occurred are now faded, but that he used to feel some concern for his victim’s parents, but hardly thinks of them any more.’

In the same year Dr Stephens said Percy needed to be able to offer an insight into himself if he was ever to be understood. ‘I doubt whether he ever will and expect that he will remain in jail until he is made safe by advanced old age or physical disease.’

According to a parole report Dr Stephens thought Percy was ‘a highly dangerous, sadistic paedophile who should never be released from safe custody. He is not certifiable neither is he psychiatrically treatable and he is totally unsuited to a mental institution. If Percy is ever so transferred he will in all probability earn some degree of freedom as the result of reasonable and conforming behaviour. The consequences of such freedom could well prove tragic.

‘At this stage it remains the combined opinions of Dr Stephens and the writer that Percy be contained in a maximum security environment for the rest of his life.’

By 1985 he had not seen his family for two years. He appeared not to care. The only time he showed emotion was when it was suggested that he would be transferred to a country prison. ‘Percy, whose face was inscrutable, the eyes cold and mesmeric, suddenly displayed emotion. His lips trembled convulsively as he emotionally stated that he did not want to move from J Division because he had “his computers there”.’

He started to write computer programs to help intellectually disabled children learn to read and was visited once a month by a volunteer social worker. Bob Hawke was Prime Minister, Alan Bond still a national hero and Christopher Skase had a solid reputation and sound lungs when Percy had served fifteen years in jail. A prison report in 1985 said ‘It has been mentioned that he is suspected of committing other child murders and if ever taken off the Governor’s Pleasure list may be charged by the police with other murders.’

One of the original homicide detectives, Dick Knight, who was to go on to become a respected assistant commissioner, remained convinced that Percy had killed before he attacked Yvonne Tuohy. He argued that no-one could have committed the Westernport murder ‘cold’ and that it was likely he was responsible for earlier crimes.

Files from around Australia were reviewed and unsolved child killings examined. Percy was considered a suspect in the abduction murders of Christine Sharrock and Marianne Schmidt on Sydney’s Wanda Beach in January, 1965, the three Beaumont children in Adelaide in 1966, Alan Redston, a six-year-old murdered in Canberra in September, 1966, Simon Brook, a young boy killed in Sydney in 1968 and Linda Stillwell, 7, abducted from St Kilda in August, 1968. Thirty years later the questions remained unanswered.

Dr Stephens said Percy was a dangerously abnormal personality, but not mentally sick in the accepted sense.

He was moved against his will to Beechworth prison in July 1986. At first he was unhappy because he did not have access to his computer and did not like the cold weather. He said ‘he wasn’t holding his breath’ waiting for a release date. The penny had finally dropped.

Six psychiatrists interviewed Percy and none found signs of treatable mental disease.

Dr Richard Ball, by then Professor of Psychiatry at Melbourne University, saw him again in February 1988. He reported that Percy refused to talk to others and spent most of his time either quietly reading, listening to the radio or resting, staring into space.

‘In a formal sense I suppose he could be regarded as without psychiatric illness,’ Dr Ball wrote.

Professor Ball said he didn’t believe Percy’s statements that he couldn’t remember what happened over the killing. He said he offered Percy the chance to take a truth drug, purely to judge his reaction. He refused the offer. ‘I think this man has always been very secretive about his fantasies and his actions. It is very clear of course that for many years prior to his apprehension he had successfully hidden these from public scrutiny, even when living in a communal setting such as the navy.

‘I have the feeling that this man is dissimulating and is just not prepared to admit his feelings and impulses.’

As a test Professor Ball decided to put Percy under pressure, bringing up horrible details of the torture and murder he had committed. ‘He did not appear distressed in any way. There was no evidence of sweating, raised pulse rate, his respiratory rate remained unchanged, his colour was no different, his eye contact remained exactly the same. I might simply have been talking about the kinds of cheese that one eats.

‘I think he must be regarded as having an abnormal personality with major sexual deviation and I cannot assure myself that this has changed for the better.’

Professor Ball added that the problem might get worse, not better. ‘I suppose one needs to consider the possibility that sometimes age withers control rather than decreasing drive.’

By 1988 Percy’s parents had retired to live in a caravan park and his younger brother operated the family’s car air-conditioning business in Queensland. The parents went on an extended holiday, travelling around Australia.

Percy told prison officer he no longer had fantasies about children and wanted to be released. He said talk of him being involved in other child murders was a fixation of the media.

He still received an invalid pension from the navy and had saved $9000. Visits from his family became less frequent and he had not seen his brothers for five years. The mail chess games with his closest brother stopped years earlier.

He smoked, did not take illegal drugs and was considered fit. His transfer to Beech worth failed due to some ‘hassles with blokes over a number of things.’ He returned to Pentridge seven months later. In September, 1987, he was moved to Castlemaine jail.

His favourite television program was A Country Practice.

He began to age, lose his hair and develop the defeatist attitude of a man who has realised he may never be freed. ‘That’s what jail does to you,’ he said.

His one outside friend, volunteer social worker, George McNaughton, retired and lost contact. In September, 1988, he was stabbed in the chest by another prisoner at Castlemaine who falsely believed he had killed the inmate’s niece. Percy escaped serious injury.

He followed a vague interest in following Fitzroy in the football and kept an interest in Test cricket.

In 1990 Dr John Grigor from Mont Park Hospital suggested Percy be moved from prison and treated with drugs to suppress his sadistic sexuality. It was the first hope for Percy in years, but it failed to eventuate.

In 1991 he was described as an ‘oddball, but no trouble whatsoever.’ Prison officers said he mixed only with fellow sex offenders who, like him, refused to take responsibility for their crimes.

In his sixteenth review his interviewer tried a different approach to get through the ‘cold and remote’ veneer. For years Percy would answer all questions with a detached, rehearsed response. This time he was caught off-guard. ‘Why do you think society takes such a dim view of people murdering children?’ he was asked.

Then Percy did something he had rarely done in twenty years — he laughed.

‘Why, there would be nobody left, would there?’ he spluttered.

Wrong answer.

The interviewer wrote in his conclusion, ‘Percy presents as an unacceptable risk and as such should be confined in the safe and, above all, secure custody of a correctional facility indefinitely.’

In 1992 psychiatrist Dr Neville Parker reviewed the case. He said Percy was not insane and the Supreme Court jury had got it wrong. ‘There was nothing at the time to suggest that he was psychotic when he committed the crime, nor that he had ever had a mental illness.’

He said he didn’t believe there was any treatment that ‘could hold out any hope of changing this man’s very perverted sexual drives.’

By 1992 he had effectively given up hope of ever being released, believing psychiatrists had preconceived ideas about him.

In 1993, when asked about his crime, he said he didn’t think about it and said his victim could have been ‘hit by a bus a week later and died.’ He refused to join any therapeutic programs. The interviewer said Percy’s only apparent regret was the crime had ‘stuffed up’ his life.

Professor Paul Mullen wrote in 1993 that Percy was sane. ‘The wisdom or otherwise of the court’s finding in Mr Percy’s case may be open to question but it is not open to modification.’

He said it was unsatisfactory that Percy was still in a jail but there was no secure facility suitable for him outside of the prison system.

By 1994 he had more than $25,000 in bank accounts and investments in gold. His navy pension was forwarded to the family business.

He played cricket once a week at Ararat and worked with his computer.

In 1995 Attorney General Jan Wade said she wanted to know if there were any moves to transfer Percy to a hospital because of the ‘need for the strictest security at all times.’

In 1997 he was developing a computer program to retrieve cricket statistics and remained an avid newspaper reader. According to his prison review: ‘Currently the objective with Mr Percy can only be for reasonably humane, long-term detention.’

After spending five years in Ararat he was involved in carpet bowls and organised intra-prison competitions, but only at a superficial level. He was still, in 1998, marooned on an emotional island the way he’d always been.

He’d had what was described as a ‘remarkably uneventful prison history.’ He had no friends and had made no efforts to deal with his problems.

He outlasted his investigators and most of captors. He outlasted three of the jails where he was an inmate: Beechworth, Pentridge and Castlemaine have all been closed.

His prison record showed he was one of the best-behaved inmates in Australia. In November, 1995, he was fined $60 for having too many educational tapes in his cell.

A little earlier he had been transported from Ararat to Pentridge for an assessment. He was taken in a private prison van that had windows. He was, noted an observer, ‘clearly elated by this experience as it is perhaps the first time Percy has viewed the open country side in almost twenty-five years.’

FINAL judgment of Justice Eames, delivered on 30 September, 1998:

The notes seized from Mr Percy’s car after the killing of the young girl disclosed that her abduction and death were not spontaneous events, but occurred very much as the notes anticipated that such events might occur.

In 1971, in his cell, it was discovered that Mr Percy had comprehensive notes describing even more horrific fantasies concerning abduction, imprisonment, torture, rape and killing of children. Also located was a collage of newspaper photographs of children, with obscene additional artwork in Mr Percy’s hand.

The notes are of the most horrifying nature, which, again, I consider it unnecessary to describe in detail.

Mr Percy had written a complex chart, with first names given to proposed victims, in which he traced a pattern of conduct which would take place over many years involving the rape, torture and killing of named children.

Among the first names of the children referred to in these 1971 notes were some names which coincided with those of children of a family known to him, which family he had occasionally visited at the time of his arrest.

There were, too, some other references in the notes which suggested that the perverted fantasies did relate to those children, even if other names used were those of imaginary children. I have before me a statement by the father of those, now adult, children, urging that Mr Percy not be released.

Mr Percy did not give evidence to me, and his assertion to those who interviewed him — that he no longer holds violent sexual fantasies — has not been tested.

There is no doubt, whatsoever, in my opinion, that both at 1969 and at 1971 Mr Percy was indeed a very dangerous man whose release from custody would have been inconceivable. The question is whether he remains such a dangerous person.

In my opinion, an examination of the 1969 and 1971 material, together with knowledge of the facts surrounding the killing, tend to confirm that not only was Mr Percy very dangerous at the time, he remains so, because the underlying sadistic condition was then, and remains now, deeply entrenched. He has received no treatment of any kind which might have changed that situation. He has shown no real interest in having such treatment. He has demonstrated no significant remorse or anxiety, at least none which I find credible, as to the circumstances which caused him to kill.

Because I am satisfied that Mr Percy holds those fantasies, then, in my opinion, the conclusion is irresistible that he remains as dangerous now as he was in 1969 and 1971.

Prior to, and during the course of, my hearings several articles appeared in the newspapers which speculated that Mr Percy may have committed more killings than that of Elizabeth Tuohy. There is no evidence before me to support that assertion.

Amongst the materials placed before me was a statement by Detective Senior Constable K. S. Robertson of the Victoria Police, dated 5 May, 1970. In that report Robertson referred to an interview conducted with Mr Percy about the deaths and disappearances of other children, both in NSW and Canberra. I did not hear any evidence from Mr Robertson. At its highest the statement of Mr Robertson records Mr Percy’s agreement that on other occasions prior to the death of Elizabeth Tuohy, whilst on beaches in New South Wales, he had sordid thoughts towards children and his agreement that he might have committed other offences had not the children been in the company of their parents.

The note records that police had no evidence to connect Mr Percy to any other killings. Only one item of ‘evidence’ was advanced. When questioned about one killing in Sydney he is recorded as having said: ‘I could have done it but I can’t remember.’