THERE was just enough late Saturday-night traffic to remind them of what they were missing.

Sergeant Gary Silk and Senior Constable Rod Miller were in an unmarked Commodore, sitting off the Silky Emperor Chinese restaurant in Warrigal Road, Moorabbin, with odds of 200-to-one against anything happening.

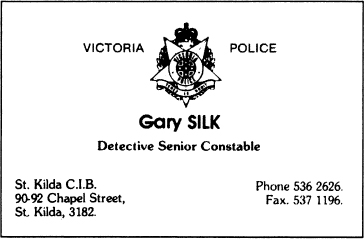

Miller had a wife and a seven-week-old son at home. Silk was single and treated his colleagues at St Kilda as his extended family. Both were popular and respected officers in the Victoria Police. Both could think of better things to do on a Saturday night. Silk would have preferred to sit with his mates, downing a few ouzos and coke, while watching his beloved Hawthorn Football Club beat the Brisbane Lions that night. Those who know say he probably listened to the game on the radio while sitting in the car looking for crooks.

For Rod Miller, leaving home was difficult since his wife, Carmel, and son, James, had come home from hospital. It was his first child and it seemed likely he would rather spend a Saturday night at home with the baby and his wife than sitting in a police car listening to a footy game. But on Friday, and again on Saturday, up to sixty police were doing the same thing, from Frankston to Brighton, and across to Nunawading and Box Hill. This was Operation Hamada.

Armed robberies on so-called ‘soft targets’, such as takeaway food stores, restaurants and convenience shops, soared by twenty-six per cent in 1997-98. Police knew there was nothing ‘soft’ about suburban armed robberies from the victims’ viewpoint. When a gun is stuck in someone’s face they can remain traumatised for years.

That’s why, in July, 1998, senior police launched a rolling strike-force of police, moving from district to district to deter armed robberies.

But the August operation was bigger than a well-publicised police show of force to deter armed robbers; this was designed to nail a gang that may have been active as far back as 1992. In the two years up to 1994 bandits robbed twenty-eight restaurants and shops in the eastern suburbs. They were never caught. In 1998, there have been eleven similar robberies — five of them on Chinese restaurants — leading police to believe the same offenders may be involved.

For months, the armed robbery squad has been trying to identify the robbers who commonly raid Chinese restaurants around closing time on weekends, when the takings are greatest. They tie up staff and patrons, often robbing the customers. Sometimes they would wear novelty rubber masks — the scariest being ‘Bob Hawke’ faces — as disguises. Senior police authorised an operation to sit off as many likely targets as possible in the hope of grabbing the robbers at the scene.

In each police district where the bandits had been active police chose four to six likely targets. It was based on logic and a little guesswork.

For officers with a watching brief it seems unlikely anything will happen. This time, it did.

As restaurants go, the Silky Emperor is isolated, sharing Warrigal Road with car yards and warehouses. Behind it is a sprawling industrial estate of panel-beaters, car wreckers and small factories. It was remote and had a main roadway at its front door for a fast exit. That made the Silky Emperor vulnerable, a soft target.

It was on a list of about six Moorabbin targets to be watched by police in unmarked cars. Similar lists were drawn up for Frankston, Dandenong and Nunawading. Common among the targets were that they were medium-sized, with few staff and in isolated locations.

The Silky Emperor was a typical target, but Silk, 34, and Miller, 35, were not supposed to be there. They had been assigned to sit off another restaurant in Moorabbin district, but that had closed without incident.

They were both known as dedicated officers who loved the job. And so it seems, because they drove to the Silky Emperor as back-up for another car from the Moorabbin Regional Support Group that had been stationed there.

It is understood that before midnight, Sergeant Silk saw something that alerted his suspicions. A car, since described as small, dark-coloured and of Asian manufacture, moved slowly by the restaurant and stopped briefly. About twenty minutes after midnight, it reappeared.

The two officers in the back-up unit decided to intercept it. Silk and Miller followed the car into Cochranes Road. As they did, one of them placed the portable blue light on the roof of the Commodore and switched it on. They did not switch on the siren because it still appeared to be a routine intercept.

The dark car pulled up in Cochranes Road and the police vehicle stopped behind it.

Having seen the move, the second police car followed the Commodore’s path into Cochranes Road. As they drove past the scene, its officers noticed nothing untoward. By then, Silk and Miller were out of the unmarked Commodore and talking to the driver of the dark car. The body language indicated all was under control; it was just another routine check during a boring shift.

The unknown driver was wearing a blue-checked shirt, jeans and runners. He was about 182 centimetres tall. The three were standing in front of the police car.

The second police car continued down Cochranes Road about 200 metres where it made a U-turn and parked to observe from a distance.

Seconds later there was gunfire. The police in the second car saw the sharp flashes from the gun muzzles. They grabbed their bulky ballistic vests from the car boot and put them on. They didn’t know whether it was police or suspects doing the shooting, nor how many gunmen there might be.

They were faced with a life and death dilemma. Do they chase the suspects, (police now know there were two) or look after their mates? The two police decided to go to the aid of their colleagues. The killers’ car sped out of the district while the police attempted first aid.

Sergeant Silk died almost instantly from a gunshot wound to the head. He was also shot in he stomach and hip. One of the first police at the scene knew him and although he could see he was dead, he was filled with the desire to put a pillow under his head, to make him comfortable. He knew he couldn’t. Years of police training told him not to touch the crime scene.

Constable Miller was shot in the abdomen but was able to return fire. As a former SAS soldier he was a good marksman. Police believe the killer’s car may have been struck and could bear gunshot damage.

At 12.27, an emergency call went in to Moorabbin ambulance station, and two ambulances, including an intensive care vehicle, were dispatched a minute later. Ambulance officers were at the scene within ten minutes. They realised they could not help Sergeant Silk, and were directed to Constable Miller, who had struggled back to Warrigal Road, where he had collapsed.

There are three possibilities: He ran from the gunman who chased him to finish him off. He chased the gunman while wounded, then collapsed. Or, knowing he was seriously injured and bleeding profusely, he ran back towards the restaurant for help.

If so, he didn’t make it.

When he was put in the back of the ambulance he pulled off his oxygen mask and told a colleague he was dying. ‘I’m fucked,’ he said.

Constable Miller was transferred to the intensive care ambulance and driven to the Monash Medical Centre, but he died hours later.

Sergeant Silk had been in the job thirteen years. He had wanted to be a policeman as long as anyone could remember. In year eight he had been asked to write an autobiographical essay for school. In it, he said he wanted to join the force.

He had worked at Port Melbourne, the prison squad and St Kilda, in uniform and as a detective. He had cradled the head of a colleague shot during a drug raid in Hawthorn and had learned the need to be careful and well-prepared when on the street. In an occupation where people can be judged harshly, no-one had a bad word for a man seen as a hard-working investigator who loved the job and was one of the most popular characters at the St Kilda station.

Rod Miller had seven years experience after joining the police in his late twenties. He was stationed at Prahran and colleagues said his main interest apart from work was his wife Carmel and baby son, James.

Only weeks earlier he had sat and told his wife what sort of father he intended to be. His own father had died when he was a toddler and he told Carmel he intended to be there for his own son. He vowed not be a part-time dad and take his son for granted. Through his own background and loss he knew that every day was precious and how important a father was to a boy.

All James Miller will have is other people’s memories of his father and yellowing newspaper clippings of how he was killed on duty.

When the Operation Hamada surveillance teams were briefed, they were warned of the possible dangers and told not to tackle the armed offenders, but to observe and call for back-up.

Some top-ranking police had expressed concern over the operation because of the possibility of armed confrontation. Under Project Beacon, the force’s safety-first program ‘The safety of police, the public and offenders and suspects is paramount.’

Police considered allowing detectives to continue to try to identify gang members, or placing officers in every possible restaurant. After an internal briefing it was decided to proceed with a blanket operation.

Asked if the officers should have been wearing protective vests, Assistant Commissioner George Davis said: ‘It’s easy to be wise in hindsight. The bullet-proof vests we have are cumbersome and are impossible to wear for the whole duration of an operation like this.’

Operation Hamada has been cancelled.

A team led by Detective Chief Inspector Rod Collins, the head of the homicide squad, was set up to investigate the murders.

Hundreds of police were used to chase down snippets of information provided through thousands of tips from the public. Police volunteered to work on days off. Others wanted to cancel holidays.

It was a crime the force and the community needed to solve.