The tempo of armed conflict in Northern Ireland fluctuated according to the bigger political picture. Violence peaked at times of great intercommunal strife and troughed at times when breakthroughs were widely thought to have been made on the constitutional front. Throughout Operation Banner the Army was issued with a number of directives from Whitehall, which firmly subordinated military operations to wider policy goals. Moreover, the campaign also ebbed and flowed as the threat from terrorism evolved. In 1969 and 1970 the Army kept a tentative peace, while the decision by the IRA to go on the offensive in 1971 saw British troops respond with a counter-insurgency drive against the insurgents. With the advent of ‘police primacy’ in 1977, the Army’s role would be scaled back over the remaining 30 years of Operation Banner to one of providing military support for the RUC in counterterrorist operations.

The violence that gripped Northern Ireland in 1971 posed a number of difficulties for military commanders on the ground. Lieutenant-General Sir Harry Tuzo, General Officer Commanding (GOC) Northern Ireland between 1971 and 1973, was a seasoned soldier more accustomed to operating in colonial theatres like Borneo than the domesticated surroundings of Northern Ireland. In colonial outposts the Army knew who the enemy was, why he was the enemy, and above all how to apply the right amount of military force in order to defeat him. In Belfast and Derry/Londonderry the centre of gravity had shifted and it was proving infinitely more difficult to win over the ‘hearts and minds’ of the local Catholic population, especially when it was so utterly opposed to the Unionist administration. The IRA, backed up by the newly swollen ranks of disaffected nationalist youths, ensured that the military’s counter-insurgency tactics soon floundered.

General Sir Harry Tuzo at Sovereign’s Parade at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst in 1973. Tuzo was General Officer Commanding Northern Ireland between 1971 and 1973. Behind him stands the then-Commandant, Major-General Robert Ford. (Courtesy of the Sandhurst Collection)

In coming face-to-face with the civil disobedience engulfing the province, Tuzo was determined to tackle the threat head on. He dismissed criticism from Unionists in border areas that troops were not doing enough to protect them or that the Security Forces had all but adopted a defensive posture. ‘Anti-guerrilla tactics,’ he wrote at the time, ‘often appear in this light, especially in a civilised community where the rule of common law still has a part to play’. Tuzo concluded perceptively, ‘[t]he hard fact is that in guerrilla war the enemy holds the initiative for large parts of the time and information is the key to his defeat’. Without the support of key sections of the population the flow of information soon dried up.

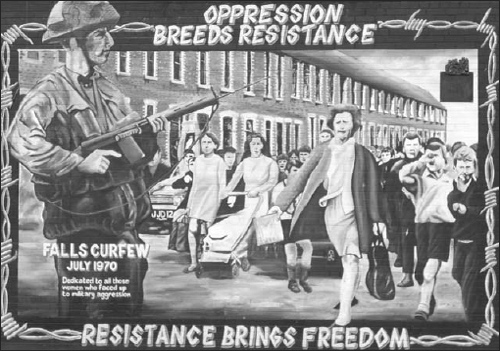

This mural on the Falls Road depicts the events of 3–5 July 1970, when the Army imposed a curfew on the area. Many of the tactics used by troops, such as stop-and-search, had been used extensively in colonial policing settings. (Aaron Edwards)

In the Bogside, like in so many ghettoized areas across the province, the Catholic population had now turned against Tuzo’s soldiers. The ‘honeymoon period’ enjoyed by the troops following their initial deployment in 1969 ended abruptly and without any real prospect of reconciliation. Instead of being treated to cups of tea and sandwiches by Catholic housewives, British soldiers were now greeted with gunfire, bombs and widespread civil disorder.

Early attempts to quell rioting – or ‘aggro’ as soldiers called it – were clumsy. Large-scale cordon-and-search operations served only to alienate Catholic working-class opinion. Furthermore, the Army’s ability to respond to the embryonic IRA propaganda campaign was amateurish, and, in the words of one former staff officer, speaking to the author, it ‘simply had not been thought through’. In all this General Tuzo was working at a disadvantage. The Stormont and London governments were constantly quarrelling over security matters. The confusing political signals made it much more difficult for the soldiers operating on the ground whose advice Stormont ministers were reluctant to accept. This was to have tragic repercussions in the early 1970s.

In a cordon-and-search operation known popularly ever since as ‘the Falls Road curfew’, Tuzo’s predecessor General Ian Freeland reluctantly ordered soldiers into the Lower Falls in Belfast on 3 July 1970 to search for IRA weapons. In the unfolding drama, rioting broke out, the air became thick with plumes of smoke billowing from burning vehicles and homes, and soldiers fired numerous CS gas canisters to disperse the crowd. The CS gas drifted into residential homes, choking their occupants, many of whom were desperately trying to carve out an ordinary existence for themselves amid the chaos. Matters were made infinitely worse when a curfew was imposed, playing straight into the IRA’s hands.

As a result, Tuzo and his deputy, Major-General Robert Ford, soon found themselves confronted with the perennial difficulty of drawing out the insurgents into a clash with the Security Forces, especially since they were now firmly embedded in a community who began to see the IRA as their defenders. However, this was by no means the same story across Northern Ireland. The majority Protestant population wished to maintain the link with Great Britain and they generally supported the Security Forces. Yet for a sizeable minority, concentrated in areas hardened by generations of anti-British sentiment, the fight was less clear cut. The conundrum facing Tuzo and Ford in Northern Ireland was to take over a quarter of a century to solve.

Although the British Army’s own reservoir of intellectual thought on counter-insurgency was extensive, it was a direct product of the Army’s involvement in military interventions since 1945, in Palestine, Malaya, Kenya, Cyprus and Aden, with varying levels of success and failure. The Army’s own guide to best practice for its commanders – what it calls ‘doctrine’ – characterized insurgents in the following terms:

The insurgent is usually careless of death. He has no mental doubts, is little troubled by humanitarian sentiments, and is not moved by slaughter and mutilation. His upbringing and standard of living make him well fitted to hardship. He requires little sustenance and comfort, and can look after himself. The insurgent has a keen and practised eye for country and has the ability to move across it, at speed, on his feet. He is capable of being trained to use modern and complicated weapons to good effect.

The Army may have been well equipped to fight an arduous guerrilla war in these colonial contexts, but in the heart of British cities such as Belfast and Derry/Londonderry it was a different matter. The Army’s carelessness, mixed with the Irish penchant for drawing strength from several hundred years of perceived injustice, contributed to an explosive situation.

Major-General (later General Sir) Robert Ford was Commander Land Forces Northern Ireland between 1971 and 1973. He was present on ‘Bloody Sunday’ and was later vilified by nationalists for his role on the day. (Courtesy of the Sandhurst Collection)

Republican operations soon became more aggressive. In contrast to the defensive posture adopted in the summer of 1969, in January 1971 the Provisional IRA Army Council issued the authorization to conduct offensive operations against the Security Forces. The first soldier to lose his life was Gunner Robert Curtis, who was ambushed by an IRA unit commanded by Billy Reid from the New Lodge Road, on 6 February 1971. Gunner Curtis’s troop was on public order duty, trying to prevent a mob from attacking people at the New Lodge/Tiger’s Bay interface. The crowd broke up to allow an IRA gunman to throw a nail bomb, which was closely followed by a long burst of automatic fire. The crowd then re-formed to prevent soldiers from giving chase. Four of Gunner Curtis’s comrades were also injured. Reid was later killed when he attempted to ambush a British Army patrol on 15 May 1971, ironically at the corner of Curtis Street/Academy Street, behind St Anne’s Cathedral.

Soldiers from 3rd Battalion, The Ulster Defence Regiment, manning a Vehicle Check Point (VCP) in County Down in January 1972. The UDR was formed in 1970, becoming an integral component of counterterrorist operations in the province. (IWM MH 30540)

The IRA began to target off-duty soldiers. The brutal murders of three young Scottish soldiers (two of them brothers) aged 17, 18 and 23 on 10 March 1971 at Ligoniel, North Belfast, graphically illustrated the extent to which the IRA was determined to ‘blood’ its volunteers. Lured to their deaths by two female IRA members after a night out, each of the young men was shot in the back of the head by gunmen as they relieved themselves by the side of a quiet country road. It was not to be the last time that the ‘honey-trap’ tactic was used by the IRA. On 23 March 1973 female terrorists again lured four off-duty soldiers to a house on the Antrim Road, with the pretext of attending a party. No sooner had the women left the house than IRA gunmen burst in and frogmarched the soldiers to one of the bedrooms, where they were all told to kneel down facing the bed. The gunmen then opened fire with an automatic rifle. Two soldiers were killed instantly and the third died of his wounds a short time later; the fourth soldier miraculously survived. The IRA repeated the ‘honey-trap’ ploy again in 1981, when one soldier was murdered and another seriously wounded in similar circumstances. Such cold-blooded and premeditated acts had echoes of the ruthlessness that characterized the Jewish insurgency against British forces in Palestine in the 1940s.

By Easter 1971, the Army was dealing with mass rioting, endless blast and nail bombings, the erection of barricades and countless contacts with IRA and Loyalist gunmen on a daily basis. In its first deployment in the Lower Falls area, 3rd Battalion, The Royal Anglian Regiment, experienced a particularly busy tour. Its Tactical Area of Responsibility bordered the Protestant Shankill to the north, the Grosvenor in the south, the Upper Falls/Springfield Road to the west, and Millfield to the east. As a flavour of what units on emergency tour could expect, on 19 April 1971 alone, 177 shots were fired at the battalion; in its four months in-theatre, it suffered four fatalities and 36 wounded.

Countering such violence was largely undertaken on an ad hoc basis dictated by operational circumstances. However, from time to time the Army conducted major operations as directed from London, but with considerable political pressure exerted from Stormont. Perhaps the most counter-productive of these was internment (known by its military codename Operation Demetrius), which saw province-wide sweeps to capture senior members of the IRA. In an interview with the author, one former staff officer present at a briefing of 39 (Infantry) Brigade commanders on the morning of 9 August 1971 recalled overhearing one senior officer tell his subordinates in confident mood that ‘today is the beginning of the end for the IRA’ and that ‘without the head, the body will simply thrash around and eventually die’. The same officer talked to a sergeant from the Parachute Regiment at Palace Barracks shortly after the initial round-ups, who made the telling observation that ‘for every one we picked up we have recruited ten for the IRA’.

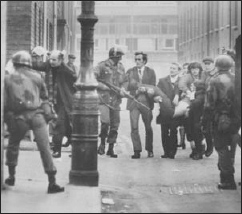

Members of 1st Battalion, The Parachute Regiment, in Derry/Londonderry on ‘Bloody Sunday’. Within the space of 30 minutes 27 people had been shot by the Paras. Thirteen people died instantly and another two weeks later. The events of that day were a turning point in the Troubles. (Fred Hoare)

Initially hostile to internment, the Army nonetheless set about implementing the political will of both the Stormont and London governments in arresting and detaining suspects. However, there were signs that within six months, Headquarters Northern Ireland was warming to the idea of relaxing the security measure in order to curry favour with the Catholic minority, as the following secret letter to No. 10 Downing Street made clear:

The Army recognise that the political initiative which is taken with the object of recapturing the confidence of the Catholic community, while retaining that of the Protestants, will have to include some move on internment if the initiative is to stand any chance of succeeding – and it is of course very much in the Army’s interest that it should succeed.

Most evidence suggests that the Army was politically sensitive to the non-military remedies proposed to end the violence; however, there remains a question mark over the extent to which it could hope to influence government policy. The Army, like other elements of the Security Forces, were the servants of their political masters. In any case, many IRA leaders had slipped the net and internment soon became an unmitigated disaster. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, violence again escalated.

Father Edward Daly waves a white flag to clear a route through the streets of Derry/Londonderry on ‘Bloody Sunday’ as the lifeless body of Jackie Duddy is carried by local people. (Fred Hoare)

One of the Army’s most controversial operations was that undertaken by 1st Battalion, The Parachute Regiment, on 30 January 1972. Later known as ‘Bloody Sunday’, the arrest operation was launched to round up suspected ringleaders of the violence that frequently accompanied illegal civil rights marches. Within 30 minutes of 1 Para entering the largely Catholic Bogside, 27 people had been shot, 14 fatally. The episode quickly soured relations between the Army and the nationalist community, providing a ‘recruiting sergeant’ for the IRA. The very use of the label ‘Bloody Sunday’ conjured up parallels with the Black and Tans’ shooting of 12 Irish civilians in Croke Park, Dublin, on Sunday 21 November 1920.

Corporal W. C. ‘Billy’ Hatton, who later won the Queen’s Gallantry Medal, detains a rioter on Bloody Sunday. (Fred Hoare)

Gun and bomb attacks increased in frequency across Northern Ireland after Bloody Sunday. In 1972–73 there were over 15,650 shootings and 2,360 bomb explosions. In 1972 alone 497 people were killed as a result of the Troubles and 4,876 injured. Fourteen per cent of these deaths were concentrated in North Belfast, with the remainder spread evenly across Belfast, Derry/Londonderry City and South Armagh.

Another dimension to the Troubles brewing in Northern Ireland during the early 1970s was the round of tit-for-tat bombings and shootings between Loyalist and Republican paramilitaries. Attacks on pubs and social clubs became the preferred course of action for all terrorist groups operating in the province. Deep-seated residential segregation made it relatively straightforward for rival groups to attack their perceived enemies without endangering those ‘on their side’. Loyalists were cruder in their targeting than Republicans, in large part because, as they argued, the IRA ‘did not wear a uniform’. The emergence of the sociopathic ‘Shankill Butchers’ gang was a direct response to the climate of fear that prompted ordinary individuals to become killers. At a tactical level Loyalist paramilitaries did not possess the same degree of technical sophistication that marked the Provisional IRA out as a deadly terrorist organization. However, this made them no less dangerous.

Bombs were the IRA’s main weapon of choice. There were countless incidents throughout the 38 years of Operation Banner involving the use of explosives (from fertilizer bombs to Semtex and C4), Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs), mortars, blast bombs, under-car booby-trap bombs and mines. In the early 1970s the IRA’s explosives were typically constructed using over-the-counter ingredients. As one former bomb-maker revealed in an interview with the author:

In the initial parts of the struggle all of our explosives were homemade. We called it co-op mix because you could have got it in the corner shop. There were different mixes. Benzene mixes, diesel mix with fertilizer and stuff like that …

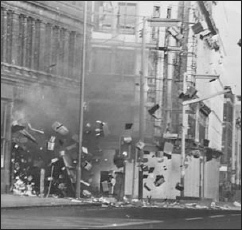

The devastating impact that explosions were to have on individuals was unparalleled; however, the IRA also decided to attack commercial targets, as a means of inflicting severe economic pressure on the British taxpayer.

In response the Army formed 321 Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) Company, mainly from the ranks of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps. Between 1969 and 1992, 321 EOD Company dealt with over 40,000 emergency calls, averaging about 40 per week. In 1991 the organization defused an 8,000lb (3,629kg) proxy bomb, the biggest bomb ever made safe in Northern Ireland, near the Annaghmartin Permanent Vehicle Checkpoint (PVC). The first Army Technical Officer (ATO) to be killed was 29-year-old Captain David Stewartson, who was blown up attempting to defuse a bomb on 9 September 1971. In 1972 six EOD operators were killed in explosions, representing 50 per cent of the unit’s operators killed during the Troubles.

The British Army set up 321 Explosive Ordnance Disposal Company to tackle IRA bombs. The unit pioneered IED disposal, responding to over 54,000 emergency calls during the Troubles. There have been over 19,000 explosions and incendiary attacks. ATOs disposed of over 50 tons of explosives in another 6,300 incidents. (IWM HU 47328)

While the IRA soon earned its reputation as a competent and sophisticated terrorist organization, this did not happen overnight. Indeed, in the early 1970s the IRA scored numerous ‘own goals’, whereby inexperienced and poorly trained bomb-makers blew themselves up while constructing, transporting and planting bombs. For instance, in February 1972 two Republicans, Patrick Casey and Eamonn Gamble, blew themselves up while tinkering with a bomb at temporary council offices in a school hall in Keady. Two IRA men, aged 19 and 20, were killed when the bomb they were transporting exploded prematurely, leaving their vehicle in a tangled mess in King Street, Magherafelt. In Crumlin, near Lough Neagh, two IRA volunteers died when the bomb they were transporting by barge exploded, killing both of them instantly. Four IRA men died when the bomb they were transporting along the Knockbreda Road went off, obliterating their car.

A bomb explodes in the centre of Belfast. Bombings of commercial targets became commonplace as the IRA’s campaign intensified in the early 1970s. (Fred Hoare)

On 9 March 1972 four members of the IRA’s 2nd Belfast Battalion working with explosives in a house on the Falls Road met a swift end when they crossed a wrong wire. On 7 April three other IRA men (all aged 17) died when they blew themselves up in Bawnmore Park in North Belfast. A devastating premature explosion on 28 May claimed the lives of a further four IRA volunteers and four civilians, highlighting the dangers of working in enclosed residential surroundings. Three more IRA men met a similar fate at the beginning of August, as did three of their comrades and six innocent civilians, when a premature explosion ripped through the customs office at Newry. Thirteen more IRA men and six others were to die in similar incidents before the end of the year. These ‘own goals’ highlighted the inherent danger of using the bomb as a lethal weapon in close proximity to the civilian population.

The year 1972 was the worst year for the Troubles. In total the IRA carried out 1,200 operations that year, mainly in rural areas of the province. Yet it also planted many large car bombs in the centre of Belfast in a bid to make Northern Ireland unstable and thereby, in the IRA’s eyes, hasten the departure of the British state. Six Protestants and one Catholic died when the IRA exploded a car bomb in Donegall Street, Belfast, on 20 March 1972. An inadequate warning had been given by the IRA. In July 1972 the IRA exploded three no-warning car bombs in Claudy, not far from Derry/Londonderry City, killing nine people, including a child. The bombing itself provoked massive outrage, particularly because it now appeared that the IRA was carrying out reprisals against civilians.

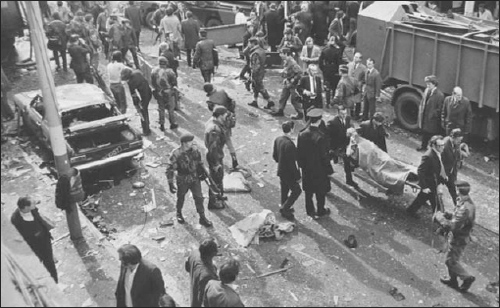

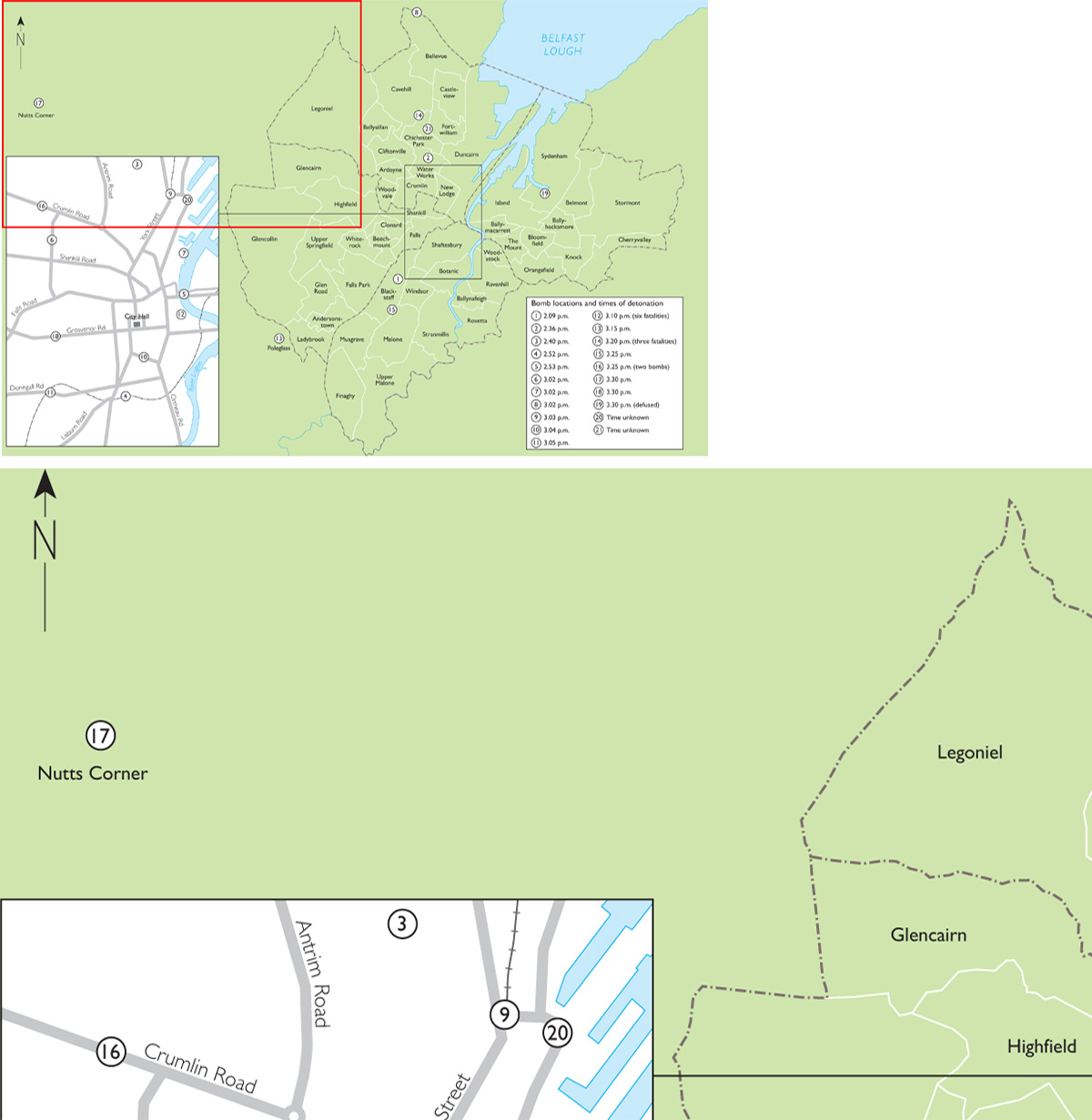

With an upsurge in violent attacks the British government sought alternative ways to deal with the IRA’s bombing campaign. In early July 1972 an IRA delegation, including Gerry Adams, who was on remand in the cages of Long Kesh prison camp, and Martin McGuinness, was flown to London for a secret meeting with William Whitelaw, the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland. The talks amounted to little and the truce declared by the IRA was terminated against the backdrop of a renewed IRA offensive. While the clumsy ‘own goals’ were removing many bomb-makers from IRA ranks, the casualties did not lessen the determination of the organization to strike at the heart of the Protestant community more directly. On 21 July 1972 the IRA exploded 22 no-warning car bombs across Belfast in a blitz that saw six soldiers, two civilians and a UDA activist die and over 130 injured within an area with a one-mile radius. The Security Forces struggled to contain the violence.

Against the increasingly indiscriminate nature of paramilitary violence, the Ministry of Defence issued a more comprehensive set of Rules of Engagement (ROE) for soldiers in Northern Ireland. Known more commonly as the ‘yellow card’, these new ROE gave troops the option to return fire if their lives were threatened (i.e. for self-defence purposes) and as long as, in their own judgement, they believed there to be a threat. As the ROE explained: ‘Soldiers may fire without warning if there is no other way to protect themselves or those whom it is their duty to protect from the danger of being killed or seriously injured.’ Owing to the high intensity of gun and bomb attacks, the ROE also authorized troops to use heavy weapons under certain circumstances:

… a company commander may order the firing of heavy weapons (such as the Carl Gustav [a recoilless rifle]) against positions from which there is sustained hostile firing, if he believes that this is necessary for the preservation of the lives of soldiers or of other persons whom it is his duty to protect. In deciding whether or not to use heavy weapons full account must be taken of the risk that the opening of fire may endanger the lives of innocent persons.

Interestingly, the ROE detailed here had already been tightened up in the wake of the Bloody Sunday shootings. What these ROE overlooked was the procedure to be used in the treatment of terrorist suspects. The Compton Committee was later commissioned to investigate whether some detainees had been subjected to inhuman and degrading treatment. Compton found that while there had been physical ill-treatment, such as the application of the so-called five techniques used previously in Aden, there was insufficient evidence of brutality.

Nevertheless, the increase in shootings and bombings left the British government with a dilemma. There was immense public pressure to do something to tackle the IRA’s campaign of violence and to ensure that the Stormont government’s writ ran throughout the province. A Top Secret Cabinet Conclusion indicated London’s thinking at the time:

The anger of the Protestant community had been such that, if he [the Prime Minister] and the Secretary of State for Defence had not immediately authorised sterner measures by the security forces against the IRA, there would have been a very serious risk of direct action on the streets on a widespread scale. The operations that had been undertaken had done much to calm Protestant opinion; nevertheless they had made no more than modest inroads upon the operational capability of the IRA, and had predictably caused some alienation of Roman Catholic opinion.

It was decided in London that the Army’s Operation Motorman would be given the green light to retake no-go areas in Belfast and Derry/Londonderry.

The aftermath of a no-warning car bomb in Donegall Street, Belfast, on 20 March 1972. Seven people were killed and 150 injured in the explosion. It was typical of the type of attacks perpetrated by terrorists on all sides during the conflict. (Fred Hoare)

Lieutenant-Colonel John Mottram, Commanding Officer of 40 Commando, Royal Marines, talks to ITN after the removal of barricades in the New Lodge Road area of Belfast. Operation Motorman was launched on 31 July 1972 to retake ‘no-go’ areas in Belfast and Derry/Londonderry from the IRA. (IWM MH 30542)

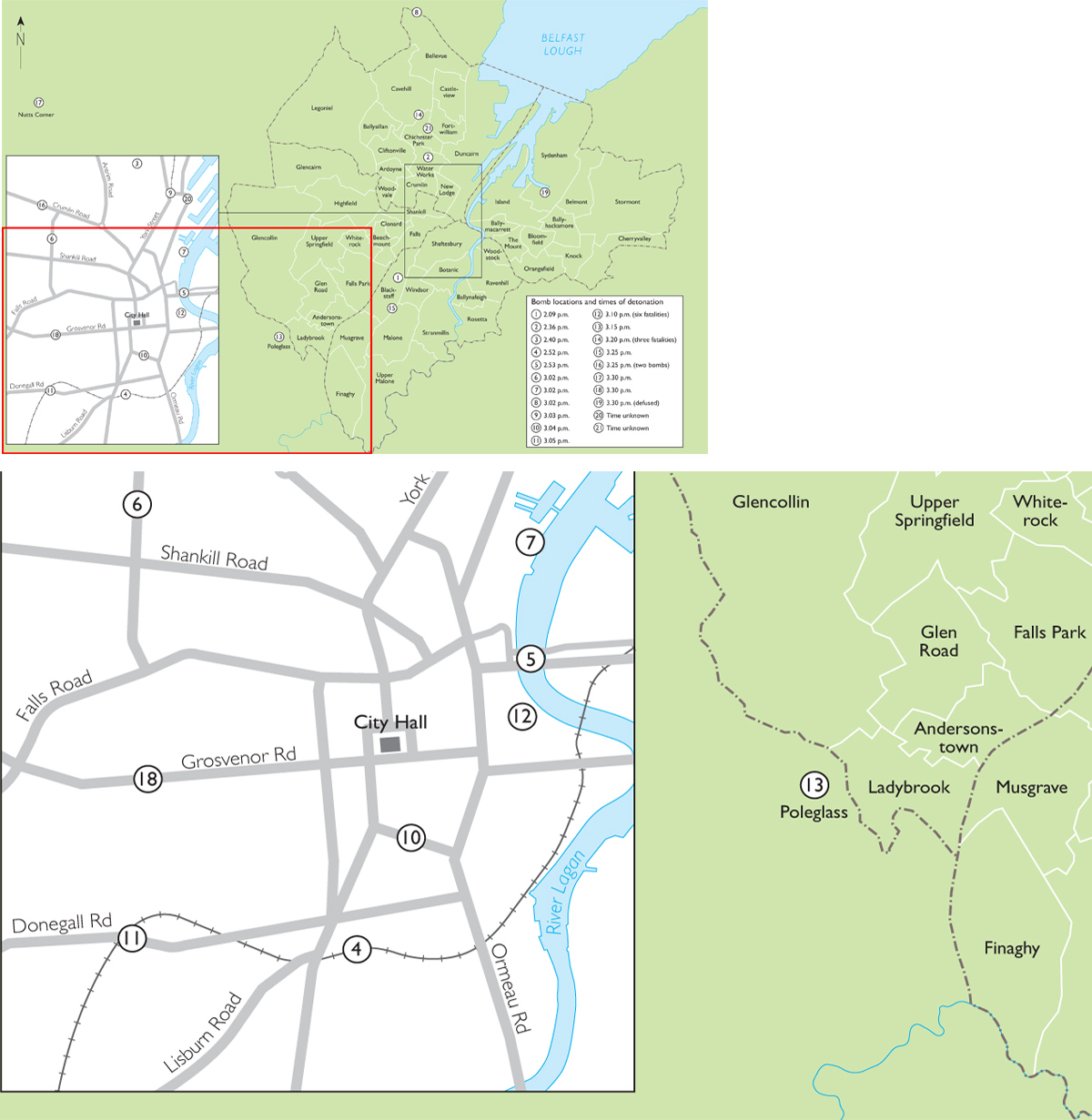

In Derry/Londonderry 8 (Infantry) Brigade had at its disposal nine regular infantry battalions, two UDR battalions, two Royal Engineer field squadrons, a troop of four Centurion AVREs (Armoured Vehicles Royal Engineers, a version of the Centurion tank) and a further seven minor units. Under cover of darkness the units moved into position on 31 July 1972. At 0400 hours the operation was launched. The infantry battalions, closely supported by the Royal Engineers, moved quickly to dominate their Tactical Areas of Responsibility and remove the barricades. In a radio broadcast, William Whitelaw made clear the government’s intention to restore law and order by any means necessary, thus ensuring that the IRA was given adequate warning of the impending military manoeuvres. As with many earlier head-on engagements, the IRA chose to retreat to their safe havens across the border. Only token resistance was met by the Army as Operation Motorman swung into action, but a civilian and an unarmed IRA member were killed. By now troops were saturating Belfast and Derry/Londonderry, taking all of their objectives by 0730 hours.

Although Operation Motorman inflicted a short-term defeat on the IRA in both cities, it did not make the organization any less dangerous in other parts of Northern Ireland. In an incident at Sanaghanroe near Dungannon at 2300 hours on 10 September 1972, three soldiers from 1st Battalion, The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, were killed and four injured when their Saracen armoured personnel carrier was blown up. All those killed were in their early twenties. The sheer force of the blast lifted the armoured vehicle off the ground and threw it 15–20 yards through a hedge and into a field. The bomb attack left a crater 30ft in diameter and 12–15ft deep. In this incident the IRA’s firing point was 70–80 yards away, up a hill within sight of the road. Two weeks later another bomb was detonated directly in front of a Saracen armoured vehicle, causing the same devastating result; remarkably, the two soldiers escaped with only minor injuries.

Soldiers board a Lynx helicopter in South Armagh. The upsurge in the use of roadside bombs and IEDs constrained the Army’s movement by road, thus making the ferrying of troops by air essential. (Author’s collection)

Republicans carried out over 35 IED attacks on the Army in August 1972 alone. As one confidential Army report from the time put it, ‘The tactics of the IRA may change as a result of Op MOTORMAN and attacks on the Security Forces in the rural areas could increase; the increased use of command detonated mines is all too likely’. The command-detonated IED was the commonest weapon in the IRA’s armoury and would become more sophisticated as the conflict progressed. Such bombs were typically constructed using 200–300lb (91–136kg) of explosive packed into a milk churn and placed under a culvert or dug into a grass verge at the side of a road. They were detonated by command wire and (later) remote-firing mechanisms, causing massive carnage. These devices had far-reaching effects on the military’s movement on the ground. In an interview with the author one soldier who survived an IRA attack described how it felt:

One night on patrol in County Londonderry we were travelling along in our vehicles and we heard a bang. We immediately assumed that it was a contact. Our Royal Engineer search adviser later came out and, after surveying the scene, informed us that it had been a 1,000lb [454kg] bomb, which had detonated as we passed over a culvert, narrowly missing us. We had a few lucky escapes.

The increasing sophistication and lethality of IRA mine strikes and IED attacks, particularly in rural areas, necessitated the development of electronic counter-measures (ECM). In an interview with the author one seasoned veteran of Operation Banner recalled how his life ‘was saved on more than one occasion’ by the ‘ECM bubble’. As the Army’s ‘lessons-learned’ pamphlet Military Operations in Northern Ireland makes clear, this ‘situation rapidly evolved into a continuous struggle between development and counter’.

In response to the growing number of military casualties caused by roadside bombs, the MoD gave more careful consideration to the use of helicopters to ferry troops. In one threat assessment the Army concluded that the main tactical weapon in the IRA’s armoury was its volunteers’ ability to withdraw hastily after carrying out armed actions by exploiting their knowledge of the local terrain:

Terrorist tactics are normally based on hit-and-run techniques both on foot and in cars. Ambushes, whether from which to snipe or command-detonate a mine, are relatively easy to set up but depend for their success on the availability of a rapid method of withdrawal. Withdrawal routes are often over fields where the terrorist has too great a head start on Security Force pursuers, or along nearby roads which cannot be reached quickly enough by Security Force vehicles which are, in any case, unsuited to chase getaway cars.

Use of helicopters increased and was soon exploited for other ends too, particularly since the Gazelle model provided a continuously available airborne reconnaissance and surveillance platform.

There were practical advantages to using the helicopter as a troop transporter, which 2 Para’s experience in South Armagh on their third emergency tour bears out. Deployed on 27 March 1973 to what Merlyn Rees later labelled ‘bandit country’, the battalion would lose four of their own men on Armagh’s roads, plus two soldiers of 17th/21st Royal Lancers and a Royal Engineer Search Advisor. Private Steven Norris and Lance Corporal Terence Brown died when their Land Rover was blown up by a 300lb (137kg) mine hidden under a culvert in Tullyogallaghan on 7 April 1973. Another soldier serving with 2 Para at the time recalls how one of his abiding memories of the tour was the blood-soaked stretchers being washed down in the shower block at Bessbrook.

In another incident four weeks later Company Sergeant-Major Ron Vines of 2 Para was killed when a pressure-pad he stepped on initiated a landmine explosion. The device’s command wire led across the border near Moybane, south-east of Crossmaglen. As Company Sergeant-Major Vines walked over to a roadside wall, the 400lb (181kg) IRA bomb detonated, killing him instantly. His wife later said that she ‘didn’t even have a body to bury’. In the follow-up operation mounted by the Army in the aftermath of the explosion two other soldiers, Troopers Terence Williams and John Gibbons of 17th/21st Royal Lancers, were blown up by a secondary device on the same spot where Company Sergeant-Major Vines had died. An Army spokesman later said that the mood of the local civilian population in South Armagh had been ‘extremely hostile’. Support for the IRA was high in Republican areas. As one former IRA volunteer recalled while speaking to the author, ‘you cannot run a guerrilla campaign without the support of the community’.

Known as ‘the workhorse of the campaign’, the Westland Wessex helicopter was in service with the RAF from the mid-1960s. It was withdrawn from Operation Banner in 2002. (Author’s collection)

As the conflict progressed the Army became better at countering IRA anti-personnel devices. The implementation of a rigorous pre-deployment training package delivered by the Northern Ireland Training Team (NITAT) to all units in the United Kingdom and Germany served to hone the Army’s tactical skills and drills. In an interview with the author, one former UDR officer who served on the Directing Staff at NITAT in Sennelager, Germany, said that troops were put through rigorous training so that when they arrived ‘in theatre’ for operations, ‘the more you could plant those wee seeds the better they were prepared’. Debriefs were especially important because soldiers soon became accustomed to the intelligence picture and how their role was vital in the overall security situation. When they eventually deployed to the province, units underwent further training in counter-IED tactics, advanced search techniques, and the application of ROE.2

By the mid-1970s the Labour government in London was exploring possible exit strategies from the conflict. London was beginning to place a premium on bolstering the profile of the RUC and the locally recruited UDR, the British Army’s youngest and by now its largest infantry regiment, under a policy of ‘Ulsterization’. This policy of handing over responsibility for security matters to local indigenous security forces had characterized Britain’s approach to counter-insurgency and counter-terrorist operations throughout the post-war period. During the Mau Mau Emergency in Kenya in the 1950s Britain opted for ‘Africanization’, in which the colonial government backed up by British troops formed, equipped and trained ‘Home Guard’ units to protect vulnerable villages from attack. In the 1960s, during the Aden Emergency, British forces again mentored Federation troops under the guiding principle of ‘Arabization’, as Aden made the transition towards independence.

The UDR was the latest in a long line of what would today be called ‘security transitions’. Established in 1970 as an instrument to counter terrorism in the province, the UDR was deemed to be invaluable because its members lived and worked in the areas where they soldiered and could thus draw on their excellent local knowledge. However, unlike the ‘B’ Specials, the UDR was born out of the political attempts to make military back-up more indigenous. While it was thought that the UDR would attract sufficient numbers of Catholics, this hope soon proved ill founded for a variety of reasons, not least because the IRA intimidated many Catholics into leaving its ranks. Formed largely along British military lines, the UDR was fortunate to be able to call upon the professionalism of its Permanent Staff Instructors, many of whom had transferred into or were on attachment from the regular British Army regiments.

In setting up a ministerial committee to examine security policy in Northern Ireland Merlyn Rees, Secretary of State for Northern Ireland 1974–76, said that it should seek

… [t]o examine the action and resources required for the next few years to maintain law and order in Northern Ireland, including how best to achieve the primacy of the Police; the size and role of locally recruited forces; and the progressive reduction of the Army as soon as is practicable.

Rees made a significant impact on Northern Ireland politics. His approach to the problems dividing Northern Ireland’s two communities tended to be ‘theoretical, almost scholarly’, according to the journalist Robert Fisk, and until the Ulster Workers Council (UWC) strike of May 1974, it seemed that Northern Ireland had ‘acquired an enthusiastic, sensitive, highly intelligent minister who could combine political flexibility with toughness’. Nevertheless, the resilience of Loyalist workers, backed up by paramilitary muscle, left him politically wounded. Perhaps the most searing critique of Rees’ handling of the UWC strike, from Fisk, was that ‘[h]e was trying to graft someone else’s ideas onto someone else’s government in someone else’s country’. The strike effectively ‘broke British policy in Ulster’ and ensured that Protestant Unionists would not have ‘power-sharing with an Irish dimension’ thrust upon them. Rees bounced back from the debacle, later forging ahead with the Labour government’s plan to place responsibility for security back into the hands of the RUC, thus laying the foundations for the successful evidence based approach that would characterize Britain’s commitment to countering Irish terrorism. The Army’s role was dramatically scaled back in favour of raising the RUC’s profile, with the assumption that the UDR would provide tactical assistance as and when required.

Northern Ireland was a unique soldiering environment. It demanded not only the confident application of infantry skills, such as proficiency in weapons-handling techniques and fieldcraft, but also a high level of Internal Security drills. The province’s terrain was variable and ranged from the 303 miles of (largely rural) border separating north and south to the tight alleyways of inner-city Belfast. Peter Morton, formerly Commanding Officer 3 Para, explained how ‘the fighting machine must be broken up into individuals and small teams who can think and operate sensitively, intelligently and always within the law no matter how provocative or frightening the situation they find themselves’.

The UDR soon became experts in the tactical side of the campaign and their numbers were increased as regular troops were withdrawn for duties elsewhere. Troop numbers rose steadily in the 1970s. At the time of Operation Motorman there were approximately 19 units on the Army’s Order of Battle in Northern Ireland, the equivalent of 21,000 troops. That figure declined to 15 units in 1975, to 13 in 1979, and again to nine in 1982. The number of troops stationed in the province in the 1980s levelled out at roughly 10,500.

The reduction in the numbers of regular troops, however, masked another important change in the operational tempo of the Army’s role in Northern Ireland. In response to the nakedly sectarian murders of ten Protestant workmen near Kingsmill, South Armagh, on 5 January 1976, Prime Minister Harold Wilson authorized the deployment of the SAS to the area. Perhaps anticipating the steady build-up of pressure from Special Forces, the Provisional IRA took the decision in November 1976 to restructure its organization along cellular lines and prepare for a ‘long war’. These internal machinations led inevitably to a resurgent Republican threat, making a permanent downsizing of the British Army garrison in the province unlikely. Moreover, there is evidence to suggest that an upsurge in IRA attacks in West Belfast had taken the Army by surprise, a jolt that, as one intelligence report candidly revealed, ‘must be seen as further evidence of our lack of tactical intelligence in West Belfast’. While good operational intelligence remained somewhat elusive in West Belfast, the military was having success in other areas.

Table 3. Security Forces strength, 1969–98

Year |

Regular |

UDR/RIR |

Army Total |

RUC Total |

Total |

1969 |

2,700 |

0 |

2,700 |

3,500 |

6,200 |

1970 |

6,300 |

2,292 |

8,592 |

3,750 |

12,342 |

1971 |

7,800 |

4,044 |

11,844 |

4,083 |

15,927 |

1972 |

14,300 |

8,476 |

22,776 |

4,273 |

27,049 |

1973 |

16,900 |

8,443 |

25,343 |

4,421 |

29,764 |

1974 |

16,200 |

7,815 |

24,015 |

4,563 |

28,578 |

1975 |

15,000 |

7,692 |

22,692 |

4,902 |

27,594 |

1976 |

15,500 |

7,645 |

23,145 |

5,253 |

28,398 |

1977 |

14,300 |

7,651 |

21,951 |

5,692 |

27,643 |

1978 |

14,400 |

7,970 |

22,370 |

6,110 |

28,480 |

1979 |

13,600 |

7,518 |

21,118 |

6,614 |

27,732 |

1980 |

11,900 |

7,376 |

19,276 |

6,935 |

26,211 |

1981 |

11,600 |

7,470 |

19,070 |

7,334 |

26,404 |

1982 |

10,900 |

7,111 |

18,011 |

7,717 |

25,728 |

1983 |

10,200 |

6,925 |

17,125 |

8,003 |

25,128 |

1984 |

10,000 |

6,468 |

16,468 |

8,127 |

24,595 |

1985 |

9,700 |

6,494 |

16,194 |

8,259 |

24,453 |

1986 |

10,500 |

6,408 |

16,908 |

8,234 |

25,142 |

1987 |

11,400 |

6,531 |

17,931 |

8,236 |

26,167 |

1988 |

11,200 |

6,393 |

17,593 |

8,231 |

25,824 |

1989 |

11,200 |

6,230 |

17,430 |

8,259 |

25,689 |

1990 |

10,500 |

6,043 |

16,543 |

8,243 |

24,786 |

1991 |

10,500 |

6,276 |

16,776 |

8,222 |

24,998 |

1992 |

12,000 |

5,417 |

17,417 |

8,483 |

25,900 |

1993 |

13,000 |

5,412 |

18,412 |

8,470 |

26,882 |

1994 |

11,759 |

5,241 |

17,000 |

8,469 |

25,469 |

1995 |

12,019 |

5,170 |

17,189 |

8,499 |

25,688 |

1996 |

11,815 |

4,855 |

16,670 |

8,424 |

25,094 |

1997 |

12,477 |

4,757 |

17,234 |

8,430 |

25,664 |

1998 |

12,346 |

4,598 |

16,944 |

8,495 |

25,439 |

Harold Wilson resigned in March 1976 and in a cabinet reshuffle, his successor as prime minister, James Callaghan, appointed a new secretary of state for Northern Ireland, Roy Mason (replacing Merlyn Rees). A Yorkshireman and former miner who had been a leading trade unionist, Mason had served as defence secretary before taking up his new post at the Northern Ireland Office (NIO). Mason was an staunch opponent of terrorism. He particularly disliked the Provisional IRA and under his stewardship would become an avid supporter of the Security Forces’ attempts to disrupt the IRA campaign.

Unlike his predecessors, Mason took a hardline attitude towards violence and his tenure as Northern Ireland Secretary was marked by an increase in Special Forces operations. As Mason made clear in a public statement in May 1977, ‘The number of special security forces such as the SAS had been substantially increased and this trend would continue’. In a letter to his successor at the Ministry of Defence, Fred Malley, Mason wrote:

We have been aware for some time of the tremendous and lasting boost for public morale which followed the posting of an SAS Squadron to South Armagh sixteen months ago. It says a great deal for the SAS Regiment’s reputation for professional skill in the counter-terrorist role that ever since their arrival, there have been calls for their operations to be extended and their number increased.

Members of the UDR patrol in the Clough/Ballykinlar area in August 1977. Situated along the picturesque County Down coast in the foothills of the Mourne Mountains, Ballykinlar was the largest military training establishment in Northern Ireland. (IWM MH 30552)

Noting the success of the Army’s role in the covert war in Northern Ireland, Mason asked Malley ‘whether more could be done’ to ensure ‘a better success rate’ and ‘to give extra credence to our claim that the Army’s expertise in dealing with terrorists continues to grow’. Mason’s correspondence with Malley on covert operations demonstrates the British government’s understanding of the changing character of the terrorist threat. In Mason’s words: ‘[T]he problem has ceased to be one of large confrontations with rioters and is one of identifying and tracing and finding evidence against small groups of terrorists’. To that end Mason became an enthusiastic supporter of the need for further covert action.

One of those serving in the ranks of the secret war was Captain Robert Nairac. A colourful if somewhat controversial figure, Nairac was a Liaison Officer between Special Forces and the RUC Special Branch. Someone who served with him told the author that Nairac ‘had a great personality and made friends easily with the result that he was an excellent Liaison Officer’. On an undercover mission to meet a contact at the Three Steps pub in Drumintee, Nairac was beaten and abducted by the IRA. One of the IRA men who tortured and killed Nairac later admitted, ‘I shot the British Captain. He never told us anything. He was a great soldier.’ In February 1979 Nairac was posthumously awarded the George Cross, Britain’s second-highest award for gallantry. Part of his citation read:

Captain Nairac served for four tours of duty in Northern Ireland totalling twenty-eight months. During the whole of this time he made an outstanding personal contribution: his quick analytical brain, resourcefulness, physical stamina and above all his courage and dedication inspired admiration in everyone who knew him.

As the Nairac case illustrates, the ‘green Army’ was not always privy to intelligence operations, which were undertaken on a ‘need-to-know’ basis. As General Sir Mike Jackson explained in his memoirs:

Intelligence and the response to it were handled on a very tight, need-to-know basis. Even when I was a brigade commander, I would not necessarily be in the loop. There would be a directive that uniformed troops were to keep out of a particular area between this time and that time because it had been ‘sanitized’ for a particular operation. I didn’t always know what was going on, but I didn’t always need to know.

With the intensification of the covert war in Northern Ireland the IRA was forced onto the back foot. Despite the odds now heavily stacked against it, though, the IRA remained resolute in its determination to drive the British Army from Northern Ireland. Speaking after his release from prison, former IRA Chief of Staff David O’Connell claimed that ‘I am more personally convinced than ever of the validity of the basic strategy of calling for a declaration of intent’. For the IRA the only option open to the British government was to withdraw.

Captain Robert Nairac GC was commissioned into the Grenadier Guards in 1972, serving four tours of Northern Ireland. He was abducted, tortured and shot by the IRA on 14 May 1977. His body has never been found. (Courtesy of the Sandhurst Collection)

By May 1977 the Northern Ireland Office had other worries, with the anticipation of a second Loyalist industrial strike. The first, in 1974, had crippled Northern Ireland’s infrastructure and led to the collapse of the power-sharing arrangement between Brian Faulkner’s Unionist Party and Gerry Fitt’s SDLP. This time, though, the Northern Ireland Office was ready for the strikers. In a secret memo sent by Mason to Callaghan, the former Defence Secretary noted:

If the strike takes place, the lesson of 1974 is that we need to display firmness and resolution from the start – and to make this clear in advance so that the action is expected. I am in close touch with the Chief Constable and the GOC. Contingency plans are being updated. Knowledge that we are doing this will become apparent and will show that we mean business.

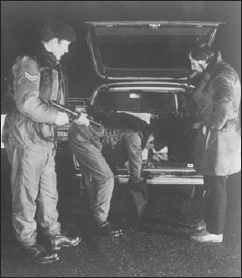

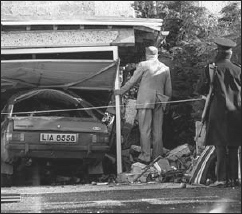

This photograph shows the scene of the booby-trap bomb explosion in October 1977 that killed Lieutenant Walter Kerr, a part-time member of the UDR. Republican terrorists used a sophisticated mercury tilt switch mechanism attached to plastic explosives to kill and maim off-duty Security Forces personnel, thus necessitating routine under-car checks. (Courtesy of Pacemaker Press International)

The widespread strike did not materialize, however. Intelligence made available to the British government suggested that the Revd Ian Paisley was ‘now having cold feet about close involvement with the Loyalist paramilitaries’. Against this backdrop other intelligence reports suggested that ‘the paramilitaries have worked themselves up into a state of considerable determination’. Nonetheless, in the words of one NIO official, after 36 hours of operations, the strike had ‘scarcely caught the public imagination’.

Apart from industrial unrest from Loyalists the other major concern was the upsurge in killings by the Provisional IRA of members of the locally recruited UDR. In the late 1970s Republicans murdered over 50 members of the UDR. One killing was particularly shocking because it illustrated how members of the UDR were routinely targeted when they were off-duty. For the terrorists these ‘soft targets’ were much easier to eliminate because of the likelihood that they would be caught off-guard and unarmed. In other words, it fitted well with the IRA’s decision to mitigate risk for its volunteers, despite propaganda that portrayed its volunteers as noble ‘soldiers of Ireland’.

This cache of IRA terrorist weapons was found during a search in Derry/Londonderry. These weapons included an M60 machine gun, three Armalite AR-15 rifles and a Star .357 Magnum pistol. Most were smuggled in by Republican supporters in the United States. (IWM HU 47343)

On 8 October 1977 Private Margaret Hearst, a part-time member of 2 UDR, was shot dead while sleeping in a caravan beside her parents’ home near Middletown. Females had been admitted into the UDR from 1973 and it was Army policy for servicewomen to be unarmed, a stance that remained unchanged until the 1990s. A gunman broke into Hearst’s parents’ home, terrorized her aunt and two young brothers, and then entered the caravan in which she and her three-year-old daughter were sleeping. The 16-year-old IRA gunman fired ten or 11 shots at Private Hearst from an Armalite rifle, killing her instantly, but narrowly missing her young daughter. The gunman and his accomplices then fled the scene to the ‘safe haven’ of the Irish Republic, where they attended a dance in Monaghan. In the follow-up operation the murder weapon was uncovered in a hedgerow approximately 550 yards south of the Hearsts’ home. Private Hearst was the first ‘Greenfinch’ (female member of the UDR) to be killed while off-duty; her murder, which was claimed by the IRA, was widely condemned.

Tragedy struck the Hearst family again in September 1980 when Private Hearst’s father, Ross, was abducted and shot dead by the IRA. His ‘crime’, said the IRA, was to admit, during torture, that he had supplied information to the Security Forces. Not only was the organization targeting off-duty UDR soldiers, but it had now sunk to a new low by assassinating members of the wider Protestant community. Actions like these exposed the sectarian underbelly of Provisional IRA violence.

The IRA preferred to attack off-duty UDR personnel principally because their targets lived and worked in the communities they served, and were therefore vulnerable. UDR personnel – both full- and part-time – had to hide their profession for security reasons and entered into a routine of checking under cars and varying routes to and from their places of work and bases, as well as taking security measures to protect themselves and their families from attack. Of the 204 UDR and Royal Irish (Home Service Force) soldiers murdered, 162 (or 79 per cent) were killed off-duty, with some 60 ex-UDR members killed by Republicans.

In an interview with the author one former UDR soldier from the Derry/Londonderry area recalled how he ‘ended up thinking like a terrorist in order to stay alive’. Opportunities for a social life were minimal, and the personal security precautions were such that one ‘routinely had to check under your car for an under-car booby-trap bomb,’ and ‘vary routes to and from home and work’. One vignette sums up the atmosphere neatly:

I was followed home from work one night. I immediately realized that I was being followed. After speeding up to 94 miles per hour I slammed on the brakes. The hunter became the hunted. I followed suit but lost them. Running into a police checkpoint I then informed them of the car registration number. It later transpired that four prominent members of the IRA were out to kill me. They were dressed head-to-toe in khaki jackets.

Many UDR soldiers automatically assumed that IRA volunteers were out for a kill. The UDR soldier interviewed by the author recalled being asked on one occasion whether he would move home, to which he replied that they would track him down wherever he went – and, besides, had the IRA decided to attack his home, it was ‘him or me’: ‘If they came to the house they would have found themselves in a battle’ but they were ‘fucking cowards’. In his words, ‘the IRA never looked their victims in the eye … except for the team led by [South Derry Republican Dominic McGlinchey] who made a point of doing that’.

Probing further, the murder campaign provoked strong feelings. The UDR soldier quoted above went on to say that ‘I lost numerous friends. How did I feel? Anger when a colleague was murdered. You wanted to seek revenge, but professionalism kicked in. Instinct kicked in and you got on with the job.’ The same UDR man saw himself very much as ‘the hunted’. The terrorists knew every move he made and he was engaged in a ‘war of survival’ on a daily basis. The primary weapon of the IRA on soft targets was an under-car booby-trap bomb. ‘If you could counter their defences they observed you from a distance and a secondary attack – a shoot – was mounted.’ The IRA, however, relied on the patterns set by Security Forces personnel, whether on or off-duty. ‘Some journeys to and from work, such as a six-mile trip, which would take ten minutes in a normal society took half an hour. I wasn’t driving directly to work and when I left work I never took the same route home.’ Even so, the unpredictability of IRA attacks and the sophistication of their intelligence, targeting and killing capabilities made the IRA a versatile opponent.

The Queen’s cousin, Lord Louis Mountbatten of Burma, pictured on his retirement in 1965, served as the last Viceroy of India in 1946–47 and Chief of the Defence Staff from 1959 to 1965. Lord Mountbatten was murdered on 27 August 1979, when his boat was blown up by the IRA. (IWM MH 28465)

This posthumous portrait shows Captain Herbert Westmacott MC, who served with the SAS in Northern Ireland. Commissioned into the Grenadier Guards, he was killed on 2 May 1980 by members of the IRA’s infamous ‘M60 gang’ as he led his men in an arrest operation on the Antrim Road. (Courtesy of the Sandhurst Collection)

Although the IRA had by now reorganized, Roy Mason warned that the group was now in possession of more sophisticated weapons and had successfully smuggled in at least one US-made M60 machine gun, which, he said, ‘has probably been used’. Because of what he called ‘their diminishing resources’ Mason believed the IRA’s aim was ‘to find something different and the M60 is a new dimension’. Mason’s comments came after off-duty UDR member, William Gordon, and his ten-year-old daughter Lesley were murdered by the IRA when an under-car booby-trap bomb blew up their family car outside their home in Maghera, County Derry/Londonderry, on 8 February 1978. His wife was waving goodbye with the couple’s baby in her arms when the bomb exploded. The Gordons’ seven-year-old son Richard, who was in the back seat at the time, was blown out of the car and onto the footpath. One eyewitness said that most of the car ended up on the roof of a house 60 yards away. Speaking in the wake of the attack and a few days after the La Mon Hotel atrocity, which claimed the lives of 12 Protestants, the Shadow Northern Ireland Secretary Airey Neave expressed the view that ‘the Special Air Service on our side could play a big role here’. Within a year Neave was himself assassinated by the INLA when he was blown up as he drove out of the House of Commons car park.

The IRA successfully assassinated other high-profile targets too. On 27 August 1979 the organization murdered Lord Louis Mountbatten, the Queen’s cousin, who was taking his pleasure boat out of the harbour at Mullaghmore, County Sligo, in the Irish Republic, when the IRA detonated a remote control bomb. Lord Mountbatten’s murder sent shockwaves through the British establishment. Two young boys, aged 14 and 15, one of them Lord Mountbatten’s grandson, were also killed in the explosion. Civilians caught up in such attacks were regarded by the IRA and their apologists as ‘collateral damage’. The murder of 18 soldiers in a co-ordinated attack later that day in Warrenpoint, County Down, demonstrated that the IRA could also execute bigger and more sophisticated operations.

Attacks on the Security Forces became much more frequent in the early 1980s. The use of heavier-calibre weapons in the late 1970s alarmed government officials and military commanders. Special Forces were tasked with recovering arms caches and arresting IRA members. In one incident on 2 May 1980 an IRA ASU (Active Service Unit, the nomenclature adopted when the IRA switched to a more tightly organized cellular unit structure) opened fire with an M60 on an eight-man SAS team as they stormed a house on the Antrim Road in North Belfast. The burst of fire killed the team leader, Captain Herbert Westmacott, instantly. The IRA unit had pre-planned the operation at a variety of different locations across the city, unaware of the presence of an informer in their ranks. Intelligence was passed on to the Task Co-ordinating Committee, the operational hub of the Security Forces based at HQNI in Lisburn, and the SAS were allocated the mission of neutralizing what became known as the ‘M60 gang’. Owing to a map-reading error the SAS team entered the wrong house, with the terrorists holed up next door, a mistake which very nearly cost the lives of more soldiers.

The Republican hunger strikes of 1981 were initiated as a means of extracting concessions from the authorities at the Maze Prison. The prison struggle gained support from many moderate nationalists. (Courtesy of Pacemaker Press International)

Local New Lodge man Joe Doherty and another member of the ASU had been trained as snipers and knew the routine of Army patrols in the area well. The IRA’s M60 gang had a fearsome reputation and was equipped with an assortment of other weapons, including a Heckler & Koch submachine gun and FAL self-loading rifles, as well as several handguns. Their gang’s modus operandi had been to ambush Security Forces patrols as they passed through Republican areas. The following year seven IRA men were charged with the SAS officer’s murder, only for two of them to escape from custody.

This mural in West Belfast depicts the hunger striker Bobby Sands. Sands became an IRA martyr when, aged 26, he died after refusing food for 66 days. (Aaron Edwards)

The M60 was again used by the IRA on 16 July 1981, when 18 soldiers of 1st Battalion, The Royal Green Jackets (1 RGJ), on a four-month emergency tour were dropped off on a covert reconnaissance mission at Glassdrummond, between Crossmaglen and Forkhill. Within a matter of hours the close-observation platoon’s position had been compromised by locals, who then alerted the IRA. Moments later an IRA ASU opened fire from across the border. The van used to extract the British soldiers was hit by 150 bullets from an assortment of weapons, including an M60, four Armalite rifles and a .303 rifle. Lance Corporal Gavin Dean was shot dead and two of his comrades wounded.

Only a few weeks before, on 19 May 1981, 1 RGJ had lost four riflemen and an attached driver from the Royal Corps of Transport in a massive landmine strike. Experts later said that a 1,000lb (454kg) bomb had totally obliterated the Saracen armoured car. Tragedy was not to end there for the regiment, however, as a roadside bomb claimed the lives of three more riflemen on 23 March 1982, a couple of weeks into their residential tour. And in one of the most sickening attacks of the Troubles, two members of the Household Cavalry, the Queen’s official bodyguard, were killed instantly when a car bomb exploded on the Mall, near Hyde Park in London. A second bomb placed under the bandstand was detonated simultaneously, claiming the lives of seven bandsmen of the Royal Green Jackets.

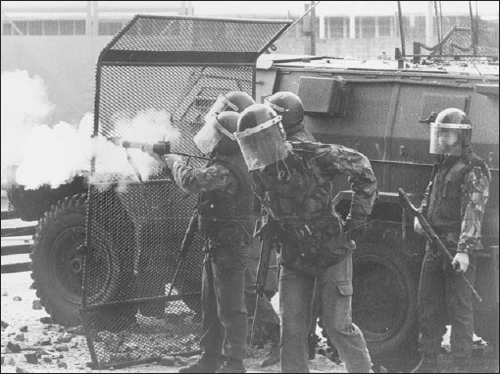

During the hunger strikes huge riots broke out across Northern Ireland. This photograph shows members of 2nd Battalion, The Royal Anglian Regiment, firing baton rounds at rioters in the Bogside, Derry/Londonderry, 1981. (IWM HU 41939)

What made the mood of this period particularly intense was that military operations were conducted against the backdrop of a Republican hunger strike in the Maze prison over a dispute with the authorities. Eventually, ten IRA and INLA prisoners were to die, including Bobby Sands, who had been elected to Westminster as an MP for Fermanagh and South Tyrone. Sands died on 5 May 1981 after refusing food for 66 days. Unsurprisingly, violence escalated in the wake of the hunger strikes. It led to a re-entrenchment of communities, and, interestingly, also to a groundswell in popular support for the dead Republicans, which in turn led to an improvement in Sinn Féin’s electoral fortunes. The IRA increased its operations against the Army and in one particularly shocking incident five soldiers were blown up and killed in a mine-strike against their armoured personnel carrier near Omagh, County Tyrone.

Republican terrorists also returned to targeting off-duty soldiers. On 6 December 1982, a devastating no-warning bomb attack on the Droppin’ Well pub in Ballykelly, close to Shackleton Barracks, killed 11 soldiers and six civilians. The INLA later admitted responsibility. Meanwhile, the IRA had renewed their campaign against the locally recruited UDR, abducting off-duty personnel before torturing and then shooting them. The fate of Sergeant Thomas Cochrane illustrates the ruthlessness and cold-blooded nature of IRA violence against UDR members. On 17 October 1982, Cochrane was travelling home from his civilian job at Glennane linen mill near Markethill, South Armagh, when IRA members felled him from his motorcycle, bundled him into a car and took him away to where he was tortured. The organization released a statement saying he was being held for ‘interrogation because of his crimes against the Nationalist community’. The IRA hoped to gain valuable intelligence about his comrades in the UDR; knowing that he was going to be killed, however, Cochrane gave his captors nothing. The IRA murdered him and dumped his body in Lislea, Armagh, five days after his abduction, proving yet again, in Ed Moloney’s words, that ‘targeting members of the … [UDR] for death was an integral part of IRA strategy’.

This memorial commemorates those murdered by the INLA at the Droppin’ Well pub in Ballykelly on 6 December 1982. The bomb ripped through a packed nightclub bar, killing 17 people instantly. It was one of the worst atrocities in the Troubles. (IWM HU 98370)

In conversations with the author one former UDR member said that using predictable routes unfortunately left off-duty soldiers open to attack from terrorists. Speaking generally about the IRA’s methods, he said, ‘When they were kidnapped they were taken to killing houses where they were beaten and horrifically mutilated… That is the reality. And a bomb was placed under the body for Security Forces personnel as a “come on”.’

One example of a ‘come on’ was the cold-blooded murder of a 62-year-old civilian chief instructor employed at Magilligan Prison. Leslie Jarvis, who attended night classes at Magee College, was shot dead as he sat in his car outside the college on 23 March 1987. His body was then booby trapped and left for unsuspecting members of the Security Forces; the device exploded a short time later, killing two policemen who were investigating the shooting.

In a bid to reduce the IRA’s capacity for mounting attacks on Security Forces personnel, the cutting edge of the Army’s Special Forces units increasingly came to the forefront in the 1980s. As Mark Urban has observed, ‘Throughout the ten years which followed [from 1976], the importance of the “Green Army” – groups of uniformed regular soldiers – in confronting terrorism fell as the role of undercover forces grew.’ The undercover war was now overtaking the overt military presence as the SAS, Military Intelligence and other security agencies intensified their covert operations against Republican and Loyalist terrorists. In statistical terms, over 30 Provisional IRA members and two INLA members had been killed and many more arrested by undercover soldiers between 1976 and 1987. Some journalists have claimed that this high attrition rate was made possible only because Security Forces intelligence ‘had been excellent’. Intelligence-gathering was the lifeblood of Security Forces operations throughout Operation Banner. One former undercover soldier told the author that ‘the covert war was a bigger battle than the overt war’.

Perhaps one of the most controversial aspects of the Security Forces’ secret war against the IRA and Loyalist paramilitaries was their ability to penetrate terrorist organizations with Human Intelligence sources, or agents. The number of these agents, known more commonly in paramilitary circles as ‘touts’, is difficult to quantify. That said, the Provisional IRA is said to have killed 70 suspected informers during their long campaign. In his book The Secret History of the IRA, Ed Moloney alleged that informers were responsible for compromising several of the IRA’s missions in the late 1980s. Moloney claims that the unit most affected by informants was the Tyrone IRA, which had killed several hundred people during the Troubles, although had itself lost a total of 53 volunteers, of whom just over half – 28 – were killed in the five years after 1987.

The SAS operation at Loughgall on 8 May 1987 resulted in the deaths of eight members of the Provisional IRA. Five gunmen in this Toyota van, accompanied by a bomb-laden mechanical digger, were ambushed while attacking the village’s RUC station. The PIRA Active Service Unit had attacked several Security Forces bases by driving into them with 500lb bombs hidden in the buckets of diggers. (Courtesy of Pacemaker Press International)

On 8 May 1987 eight men from the Provisional IRA’s East Tyrone Brigade were cut down in a hail of SAS bullets as they attempted to attack an RUC station in the sleepy County Armagh village of Loughgall. A 24-strong SAS team had been assembled in Mahon Road Barracks, Portadown, on the evening before the shooting. Outnumbering the IRA by three to one they split up into a ‘killer group’ and three ‘cut-off groups’, each taking up position. The IRA had earlier hijacked a mechanical digger; loading a 200lb (91kg) bomb into its bucket, three of the terrorists travelled in its cab and five others in the blue Toyota HiAce van. The van reached Loughgall at 1915 hours, passing the church and driving down the hill to the station before going back up. After making sure the coast was clear it returned, closely followed by the mechanical digger. At about 1920 hours the van came to a halt in front of the station. The IRA men in the van dismounted and opened fire with their automatic weapons. At the same time the digger crashed into the wall and the IRA men on board lit the fuse, at which point the SAS ambush was sprung. Over 1,500 rounds were fired by the SAS soldiers and the elite policemen who were accompanying them.

This was not the first time the IRA had attacked RUC stations. On 28 February 1985 the IRA had mortared Newry RUC station, killing nine police officers, the largest single loss of life incurred by the RUC in the Troubles. In May that year the IRA blew up a mobile police patrol, killing four officers, and on 7 December they launched an attack on Ballygawley RUC barracks, killing two policemen. This last attack was much more audacious and involved IRA volunteers raking the police station with gunfire and then blowing it up. It was a tactic repeated again on 11 August 1986, when the IRA destroyed the RUC station at the Birches, County Tyrone.

In an oration at the graveside of the dead men, Gerry Adams said that Loughgall would become ‘a tombstone for British policy in Ireland and a bloody milestone in the struggle for freedom, justice and peace’. Strategically, though, the IRA was staring defeat in the face. In the 1980s and 1990s nine out of every ten operations were aborted or failed. By now Security Forces intelligence operations were scoring huge successes.

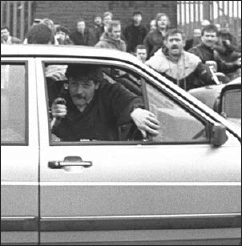

Loyalist gunman Michael Stone moves away along the fence line after attacking the funeral of the IRA terrorists killed by the SAS in Gibraltar in March 1988. Stone murdered three IRA volunteers on the day. (Fred Hoare)

This photograph captures the moment when Corporals Derek Wood and David Howes were set upon by a Republican mob. They had strayed into the path of the funeral cortège and were abducted and shot by the Provisional IRA. The mourners believed they were Loyalists attempting to attack the funeral. (Courtesy of Pacemaker Press International)

Meanwhile, Loyalist violence reached a peak by the late 1980s and early 1990s. In part this was attributable to a more honed intelligence-gathering capability and an influx of new weaponry, which permitted the UVF and UDA to enhance the sophistication of their operations. Michael Stone’s attack on the ‘Gibraltar Three’ funerals and the resulting IRA shooting of two off-duty British Army corporals reinforced the cycle of violence at this time. However, the shift from a random sectarian campaign of violence to a more focused and co-ordinated effort to assassinate individual Republicans led some Unionist politicians to suggest that the Loyalists were having an effect on the IRA. Nationalist politicians offered another reason for the successes of Loyalist paramilitaries: collusion.

Countless informants were recruited by the Security Forces, many of whom, it was alleged, took an active part in criminal acts such as extortion, intimidation and murder. It is thought that in a bid to root out informers in its ranks the IRA killed over 70 of its own volunteers. In response to allegations of collusion between some elements of the Security Forces and terrorist groups, Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government appointed Sir John Stephens, the former Metropolitan Police Commissioner, to undertake an investigation into the UFF murders of a Catholic, Patrick Finucane, and a Protestant, Brian Adam Lambert. But so protracted was the process that his findings and recommendations for the period 1987–2003 were published only in April 2003. Towards the end of his report, Stephens concluded that

… there was collusion in both murders and the circumstances surrounding them. Collusion is evidenced in many ways. This ranges from the wilful failure to keep records, the absence of accountability, the withholding of intelligence and evidence, through to the extreme of agents being involved in murder.

Controversy still surrounds these killings and other incidents in the ‘dirty war’ and continues to dominate Republican thinking on the legacy of the Troubles.

Between 1987 and 1989 the RUC dealt with over 3,000 terrorist-related incidents, of which 261 were Troubles-related deaths. The Provisional IRA had by now been developing more deadly techniques. On 24 October 1990 it unveiled a deadly new tactic, when it carried out a 1,000lb (454kg) proxy bomb attack on the Coshquin PVCP (Permanent Vehicle Check Point).3 Five soldiers from 1st Battalion, The King’s Regiment, and a civilian (the driver of the van carrying the bomb) were killed. The civilian, Patrick ‘Patsy’ Gillespie, had worked in the canteen of a local Security Forces base. His family was taken hostage and held at gunpoint, while he was ordered to drive the van and its deadly cargo to the target.

A proxy bomb attack on the Victor Two checkpoint on the Buncrana Road, Derry/Londonderry, on 24 October 1990 killed five soldiers and a civilian, ‘Patsy’ Gillespie. Gillespie’s family were held at gunpoint by the IRA and he was forced to drive a van bomb into the Army base. (Courtesy of Pacemaker Press International)

A soldier examines an IRA mortar that has been rigged to the bucket of a mechanical digger. IRA bomb-makers were masters of the ‘flying bomb’ and frequently constructed home-made mortars. This mortar was abandoned in an aborted attack on the Security Forces in Bessbrook in the late 1980s. (IWM CT 629)

The move towards Ulsterization since the mid-1970s was becoming a reality by the early 1990s. The UDR was a much more professional and adept organization. As one former UDR officer recalled in conversations with the author, ‘the UDR grew from being a part-time, bunch of colonials into a more professional organization’. It had by now been given further operational responsibilities as the numbers of regular troops began to drop off, particularly as there were now pressures coming from the 1990 ‘Options for Change’ defence review and overseas commitments in the Gulf. In the defence review a number of infantry regiments were amalgamated, including the UDR and the Royal Irish Rangers, leading to the formation of the Royal Irish Regiment in 1992.

The political and military pressure exerted on the IRA forced the organization to switch its attention to more high-profile targets on the British mainland. In February 1991 the IRA launched an audacious mortar attack on No. 10 Downing Street. A series of co-ordinated attacks on the London Stock Exchange applied further pressure, leading Unionist politician Robert McCartney to remark that ‘a bomb in London is worth 100 in Belfast’. These attacks demonstrated how the IRA’s campaign was increasing in intensity. A shipment of arms destined for Belfast was intercepted in 1994; however, there were suggestions that more than three-quarters of the consignment had successfully reached its destination.

A British soldier stands guard outside shops in the Shankill Road just after the outbreak of a feud between Loyalists in August 2000. The violence led to seven deaths, several injuries and hundreds of families having to move home. (IWM HU 98346)

While there was a dip in the number of operations mounted by the IRA, Loyalist violence continued unabated. The brutal sectarian killings of four workmen in Castlerock on 25 March 1993 and the indiscriminate attack on the Rising Sun bar in Greysteel, near Derry/Londonderry City, on 30 October that year were particularly shocking. The Greysteel massacre was exceptionally callous, with UFF gunman Torrens Knight and his accomplice heard shouting ‘trick or treat’ before opening fire, spraying the packed bar with over 30 bullets. There were 200 people in the bar that evening; it was a miracle that the attack claimed only eight victims. The Greysteel attack was mounted in retaliation for the IRA bombing of Frizzel’s fish-and-chip shop on the Shankill Road a few days earlier, which claimed the lives of nine civilians. The IRA volunteer responsible, Thomas Begley, also died as the bomb he was transporting blew up prematurely. Issuing a statement to the media shortly afterwards, the IRA claimed that the operation was intended to target a meeting of the UFF in an upstairs office. Violence continued steadily into 1994, as the IRA targeted Heathrow Airport on three separate occasions in March that year. Meanwhile it also undertook a co-ordinated assassination campaign in which a number of high-profile Loyalists were shot dead. On all fronts the violence continued unchecked with little prospect of an end in sight.

2 In order to counter ‘skills fade’ the Army also introduced ‘roulement’ battalions that would deploy for pre-defined periods of time of several months in high-intensity areas, such as West Belfast, and ‘resident’ battalions that would move their headquarters and sub-units to Northern Ireland with their families for longer tours of up to two years.

3 PVCPs gave troops the flexibility to mount a permanent presence around their patrol bases and observation posts dotted along the border. Many of the Army’s border bases were ‘supersangars’, 65fthigh watchtowers erected as surveillance and listening posts.