General Sir Mike Jackson has held every rank in the British Army from officer cadet to general. Born in 1944, he attended the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst in 1962–63; commissioned into the Intelligence Corps, he later transferred into the Parachute Regiment. Jackson served three tours of Northern Ireland. In the first, from 1970, as a captain, he was a Community Relations Officer/Unit Press Officer and later, from the spring/summer of 1971 until 1972, as a major, Adjutant of 1 Para, based at Palace Barracks; in the second, between January 1979 and December 1980, he was Officer Commanding B Company, 2 Para; in the third, between November 1989 and Easter 1992, he was Commander of 39 (Infantry) Brigade in Lisburn.

Jackson witnessed first-hand how the tempo of the Army’s military operations changed over time, from its early peacekeeping role in 1970, through to its counter-insurgency drive against the Provisional IRA, and finally into its counter-terrorist phase. Later reflecting on his service in Northern Ireland, he said he was ‘a round peg in a round hole’.

In 1970 1 Para was the reserve battalion for 39 Brigade. Jackson was Community Relations Officer/Unit Press Officer. He later remarked in his autobiography that he found this role ‘very stimulating’ and ‘relished the challenge – not least because the job took me out on to the streets wherever there was trouble’. The 39 Brigade commander at that time was Frank Kitson, who had just completed a Defence Fellowship at Oxford and published an influential book, Low Intensity Operations. Jackson said of Kitson that although he was not the most senior officer in Northern Ireland at that time, he was ‘the sun around which the planets revolved, and he very much set the tone for the operational style’. Kitson’s command appointment coincided with the IRA’s decision to begin offensive operations against the British Army.

A ruthless and determined guerrilla enemy in the form of the IRA faced the Security Forces in the early 1970s. One of its most deadly units was the Derry Brigade, at one time led by Martin McGuinness (later Deputy First Minister), which murdered over 200 people between 1970 and 1994. Since the souring of relations between the Army and the Catholic community in 1970–71, the IRA began to target and attack Security Forces personnel more directly.

The intensity of IRA attacks had been increasing markedly in the opening weeks of 1972. On 27 January, as they travelled in an unmarked car up the steep incline of Creggan Hill towards Rosemount RUC station, Sergeant Peter Gilgunn, 26, and Constable David Montgomery, 20, were shot dead, and their colleague Constable Charlie Maloney was badly wounded. The IRA gunmen responsible stepped out in front of their car and sprayed their Ford Cortina with automatic fire from a Thompson submachine gun, hitting it 17 times. Gilgunn and Montgomery were the first RUC officers to be murdered in the city for 50 years and the latest of 18 policemen to be killed by Republicans since 1969.

Interestingly, on the same day as this attack, the British Army fought a major gun-battle with an IRA unit led by Martin Meehan in Dungooley, South Armagh, during which a detachment of the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards fired over 4,500 rounds of ammunition. The IRA responded in kind, firing assault rifles and an anti-tank weapon at the troops. In response to the upsurge in violence, Defence Secretary Lord Carrington imposed constraints on the Army operating in Derry/Londonderry. On a visit to the city on 7 January 1972, Commander Land Forces (Northern Ireland) Major-General Robert C. Ford reported how ‘the Army in Londonderry is for the moment virtually incapable’ and that the minimum-force policy was failing to allow the troops to restore law and order. As he continued, ‘I am coming to the conclusion that the minimum force necessary to achieve a restoration of law and order is to shoot selected ring leaders amongst the DYH [Derry Young Hooligans]’.

A mural depicting Provisional IRA gunman Martin Meehan, who led several attacks against British troops from the 1970s onwards. (Aaron Edwards)

At 1610 hours on 30 January 1972, Jackson witnessed the Paras entering the Bogside. He later told the Saville Inquiry that ‘[I]t became almost immediately apparent that they had become involved in a firefight’. Moving forwards with his commanding officer, Derek Wilford, to get a better view of what was happening, he recalled, ‘[a]s I sprinted across the wasteground I had an absolutely firm impression that I was being shot at. What I thought was: “some bugger is firing at me”.’ Within 30 minutes 108 shots had been fired and 13 people lay dead, with another 14 injured. Soldiers manning a machine-gun post had earlier fired the shots that wounded John Johnson, who later died of his wounds.

Bloody Sunday was a tragedy for the people of Derry/Londonderry. It was a major catalyst in the further deterioration of relations between the Army and the sections of the Catholic minority who had not yet turned against them. The shootings unleashed a tidal wave of support around the world for nationalists and Republicans. On 2 February 1972, the British Embassy in Dublin was overrun and burned down by an angry mob. Meanwhile, the IRA enjoyed a recruiting bonanza, as ‘the stench of cordite was clearing from Rossville Street’, in Eamonn McCann’s words. Young men flocked to the IRA’s banner with one thing in mind: to hit back.

Soon the IRA was seeking reprisals against civilians. An upsurge in its bombing campaign reduced much of Derry/Londonderry to rubble, sending a clear signal to Unionists that they were unwanted and that ‘Free Derry’ had become a ‘no-go’ area. In Belfast the IRA exploded 22 no-warning bombs inside a one-mile radius in 75 minutes, killing nine people and injuring over 120; the day became known as ‘Bloody Friday’. In response the British government authorized Operation Motorman, a retaking of no-go areas. However, on the same day, and as a means of relieving pressure on its volunteers, the IRA detonated three no-warning car-bombs in the town of Claudy, just a few miles outside the city, killing nine people and injuring scores more. The year 1972 was the single worst year of the Troubles, with a total of 497 people killed.

The IRA carried out over 1,200 operations in 1972, mainly in rural areas. Early military intelligence reports suggested that Republicans would

… extend guerrilla warfare to rural areas of south Co. Londonderry. Hideouts and arms dumps are being constructed for this purpose. Active Service Units from Eire together with local units are expected to take part in hit and run attacks against Security Forces, and it is hoped that some of the Roman Catholic rural areas will become No-Go areas.

Violence against the Security Forces escalated in the period after the shootings in Derry/Londonderry. A total of 14 RUC officers and 53 soldiers lost their lives in the two-and-a-half years before 30 January 1972, while 26 RUC officers and 180 soldiers were murdered in the two-and-a-half years after ‘Bloody Sunday’. A startling 130 troops died in 1972 alone.

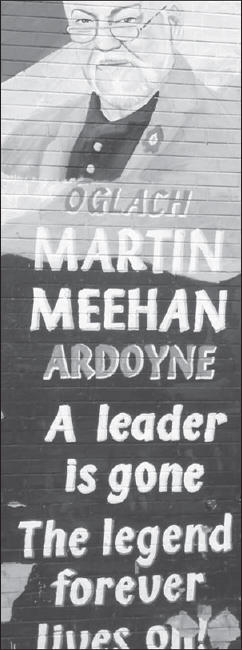

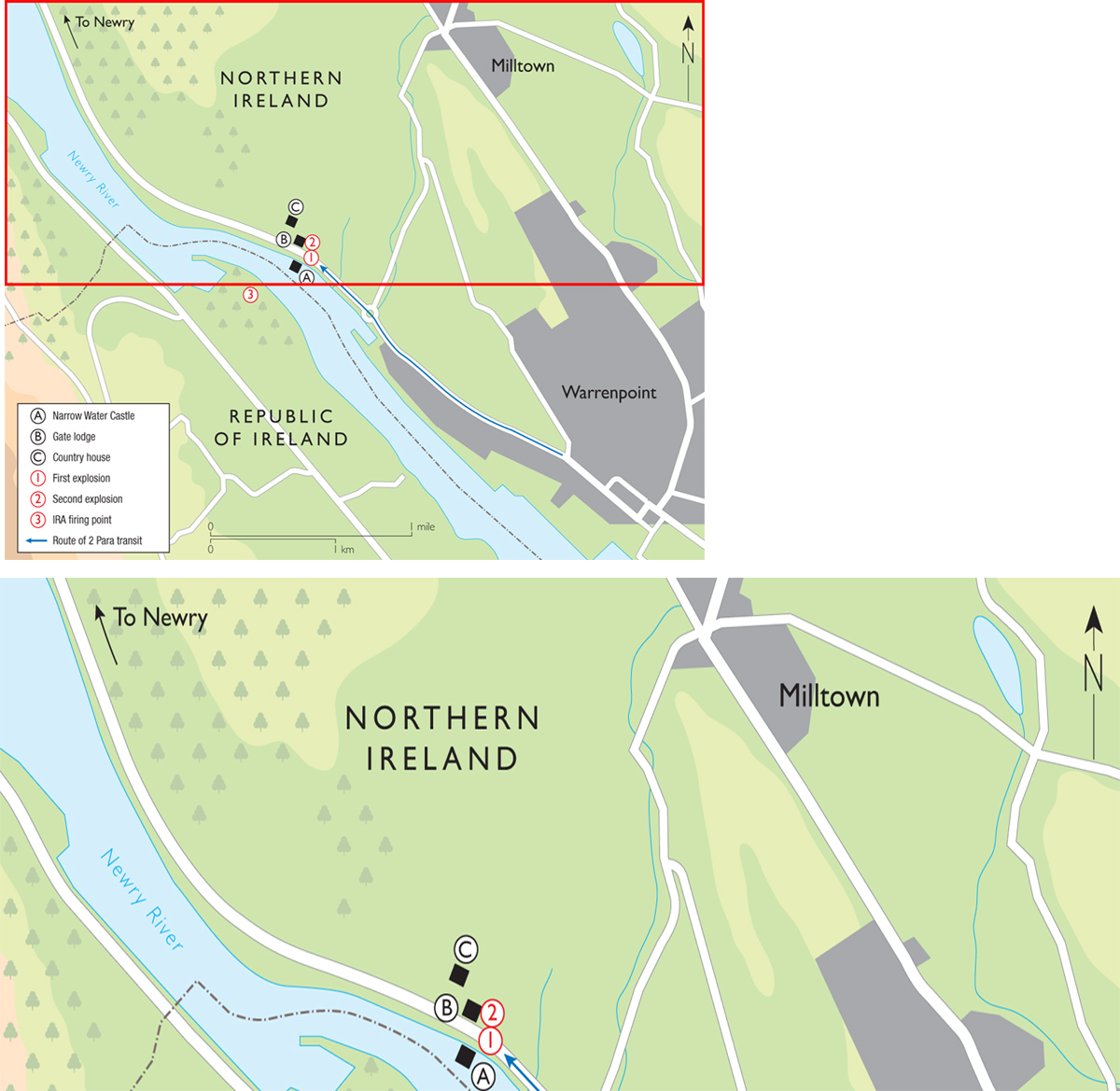

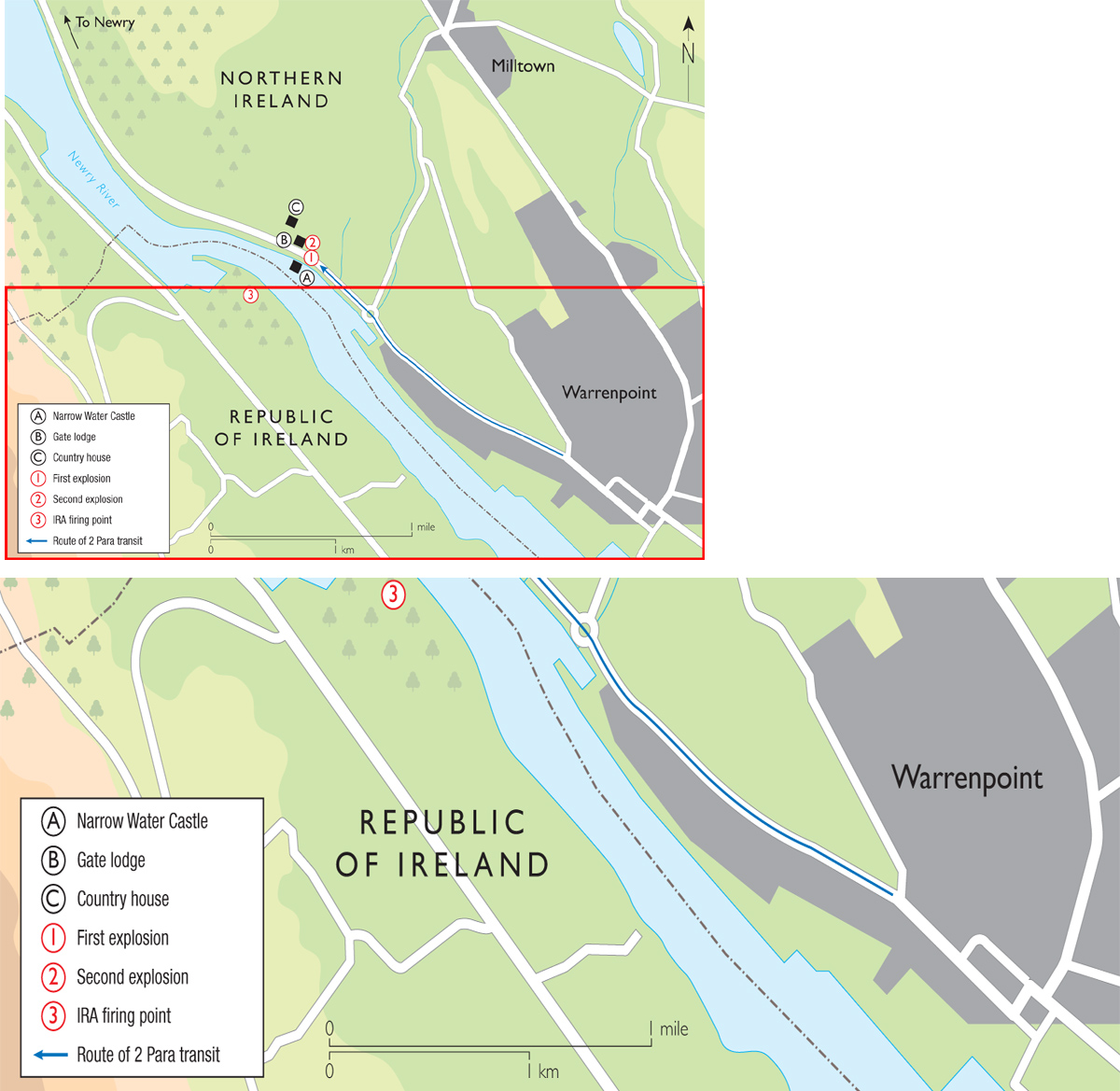

This was certainly the atmosphere Jackson left behind when he departed several months later; it remained virtually unchanged when he returned for his second tour in January 1979. He had assumed command of B Company, 2 Para, who were based in South Armagh and acted as the reserve battalion for 3 (Infantry) Brigade. Jackson had just returned from operations with his company to the headquarters of 1st Battalion, The Queen’s Own Highlanders (1 QOH), in Bessbrook Mill, South Armagh, when A Company was tasked with relieving 2 Para’s Support Company in Newry. On Bank Holiday Monday, 27 August 1979, A Company set off on a random route selected from a number of possible routes provided by the operations (ops) room in Ballykinlar. As Jackson noted in his memoirs, it was a course of action that was ‘to result in mayhem’, for the IRA had laid a meticulously planned ambush.

The first bomb, constructed with half a ton of explosives, was disguised beneath hay on the back of a flatbed lorry. The IRA detonated it by remote control as the three-vehicle convoy passed by, killing six Paras in the rear four-ton truck instantly. Those in the lead two vehicles, a Land Rover and another four-tonner, debussed to cordon off the area and help their wounded comrades. Almost immediately news filtered into the ops room at Bessbrook, where Jackson was enjoying a cup of tea in the officers’ mess. A report had come in from a nearby Royal Marines patrol that an explosion had occurred on the main road from Warrenpoint to Newry at 1640 hours. A Wessex helicopter returning from a routine mission intercepted the frantic contact message radioed by the soldiers. The crew quickly relayed it back to Bessbrook and were ordered to return and pick up a medical team and four-man quick reaction force.

The helicopter arrived at the scene to ferry away the wounded. Just as it took off – 20 minutes after the initial explosion – a second bomb, about 200 yards further along the road towards Newry, was detonated by the IRA, killing 12 more soldiers who were taking cover by a gate lodge nearly. The second explosion claimed the life of one of the highest-ranking officers to be killed in the Troubles, Lieutenant-Colonel David Blair of 1 QOH. Blair was airborne in a Gazelle helicopter when he received word of the explosion and ordered the pilot to land close to the scene. He was dropped off, together with his signaller, in the grounds of a country house, from where they ran down to the gate lodge. At this point the terrorists, who had been watching events unfold, detonated the second bomb. Eyewitnesses reported hearing heavy automatic gunfire from the Irish Republic, across the narrow canal.

Jackson recalled in his memoirs how ‘[a]s we circled before landing I could see two craters and large scorch-marks on the road marking where the bombs had been’. The scene that greeted him when he landed was horrifying. Soldiers lay screaming; ‘there was human debris everywhere’, he said, ‘mostly unidentifiable lumps of red flesh, but among them torsos, limbs, heads, hands and ears’. The Warrenpoint massacre had a profound effect on the future Chief of the General Staff. ‘I still have ugly pictures in my head from that terrible day. Once you’ve seen such appalling sights you can’t close your mind to them. But I don’t have nightmares; fortunately my temperament isn’t like that,’ he wrote. It was the biggest loss for the Paras since Arnhem in 1944.

When the Gulf War broke out Jackson was commanding 39 (Infantry) Brigade in Belfast; it was the second time that he was to miss out on combat, having been posted to a Defence Intelligence-gathering post in MoD Main Building during the Falklands War of 1982. He wrote that in ‘some ways not much had changed since my last tour’. Although there was much less mass rioting, ‘appalling atrocities’ continued. Just as he arrived he got a report of a roadside bomb that had killed three members of 3 Para in Mayobridge, County Down.

Jackson’s job as brigadier was ‘to task, to co-ordinate, to encourage and to support the soldiers: to ensure that everybody knew what they were supposed to be doing, and that they had the resources they needed, including reinforcements if necessary’. In short he commanded, managed and led his subordinates. This was to be done within a newly defined framework of ‘police primacy’ and he had regular operational meetings with his counterpart in the Royal Ulster Constabulary. As he pointed out, ‘[m]ajor decisions about how to prosecute counterterrorism operations lay with the RUC; the Army played a supporting role’. Jackson left Northern Ireland around Easter 1992, shortly before the peace process got under way, triggered by the IRA ceasefire of 1994. General Jackson’s experiences show us how military operations altered to meet the terrorist threat and they provide real insight into the commander’s war in Northern Ireland.

The then-Chief of the General Staff, Sir Mike Jackson, talks to HRH Prince William after HRH Prince Harry’s commissioning at the Sovereign’s Parade at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst on 12 April 2006. (© Dylan Martinez/Reuters/Corbis)