Northern Ireland is a deeply divided society, and one which finds echoes around the world. Like rival Greek and Turkish Cypriots in the eastern Mediterranean or the Israelis and Palestinians in the Middle East, Protestant Unionists and Catholic nationalists share one land, but are separated by religion, history and culture. Reinforcing the conflict are the overlapping – albeit divergent – national identities held by both sides. Protestants regard themselves as British and wish to maintain the union with Great Britain, while Catholics wish to jettison these ties, abolish partition and unite Ireland. The strong bond between local communities and neighbouring states is common throughout Europe and the rest of the world, and it is echoed in much of the wall art decorating urban areas across Northern Ireland. In many ways one of the most telling aspects of the Troubles is the empathy the main parties to the conflict have with those undergoing similar trials and tribulations elsewhere.

The international dimension has been a constant feature of the Troubles ever since they exploded onto the streets in the late 1960s. Indeed, for the outside world the clashes between police, demonstrators and counter-demonstrators remained the conflict’s defining images. Scenes of widespread disorder, police baton charges, masked gunmen and rioters, homes reduced to rubble, and streets awash with watercannon spray and littered with smashed glass and bricks became commonplace.

Other conflicts around the world helped to fire up the imagination of many student radicals and civil rights activists. Interestingly, the Troubles erupted at a time when feelings in Northern Ireland were already running high, inflamed by global issues such as segregation in the American Deep South and the United States’ intervention in Vietnam. In the US, armed militias like the Black Panthers took advantage of the civil disorder and could frequently be seen flanking those calling for the withdrawal of troops from south-east Asia, as well as those marching in solidarity with the North Vietnamese-sponsored insurgent groups. Ironically, some civil rights activists in Northern Ireland took to the streets to protest about these international problems more than about grievances closer to home. Unionists and nationalists would not remain insulated from the gathering storm of global protest for long.

Importantly, many IRA members saw their struggle in the context of worldwide national liberation struggles. Indeed, one former Provisional IRA volunteer admitted that at one time the organization had an ‘embassy’ in Algiers and had working contacts with the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola – Party of Labour (MPLA) and Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF). These links provided the IRA with much-needed logistical and financial support, as well as higher profile contacts with Colonel Gaddafi’s Libyan regime and the African National Congress in South Africa. In an interview with the author the same IRA volunteer said:

[I]n reality I mean the contexts were good… Giving people solidarity who were fighting a post-colonial conflict… To me it consolidated my belief that we were an internationalist group. That they could relate to our struggle because we were socialist and secular, you know. It wasn’t just a nationalist push which inevitably, fatally, alas it turned out to be.

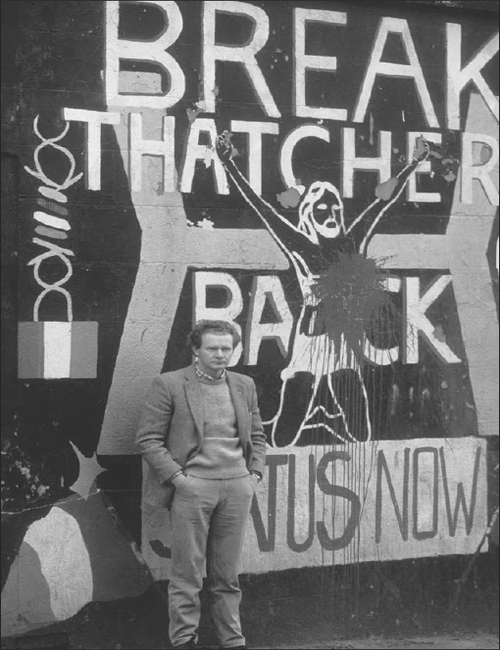

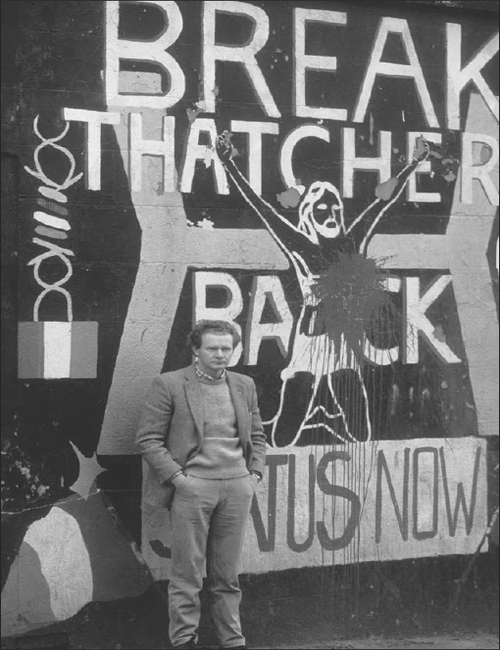

Martin McGuinness stands in front of an anti-Thatcher mural on the Falls Road, 1985. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Loyalists tended to look closer to home, by seeking support for their cause in the Protestant heartlands of Glasgow and Merseyside. Scottish historian Ian S. Wood has chronicled how this support has manifested itself in what he calls ‘90 minute Loyalists’, a term used to denote Northern Ireland soccer fans who regularly attend Glasgow Rangers football matches. Republicans have relied on supporters in Catholic parts of mainland Britain too, of course, many of whom gave the IRA financial support when they exported their armed struggle to England in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s.

Soldiers from 1st Battalion, The Scots Guards, join with RUC officers in observing a three-minute silence to remember those killed in the September 11 attacks on the United States. The atrocities turned many Republican sympathizers in the US against terrorism, thus precipitating the end of the IRA’s terror campaign. (IWM HU 98350)

The threat posed by Irish Republican terrorists was a long-standing one and dated back to Irish Republican bomb attacks in London in the late 19th century. In December 1867, in an attempt to free one of their incarcerated members, the secretive Fenian Brotherhood carried out a bomb attack on Clerkenwell Prison, London. The lavish use of dynamite meant that the Fenians demolished a row of houses nearby, killing 12 people and injuring over 50. As the celebrated Communist thinker Karl Marx observed at the time:

The London masses, who have shown great sympathy towards Ireland, will be made wild and driven into the arms of a reactionary government. One cannot expect the London proletarians to allow themselves to be blown up in honour of Fenian emissaries.

Nevertheless, bombs in England became the powerful signature piece of each new incarnation of militant Irish Republicanism over the next century. The threat of bombing would remain a thorn in the side of successive British governments, who were more susceptible to public calls for a solution to the ‘Irish problem’ to be found.

This wall mural in Hawthorn Street, West Belfast, depicts three IRA volunteers shot dead by the SAS in Gibraltar. The IRA took its ‘armed struggle’ abroad, targeting several British military bases in Germany and Gibraltar. (Aaron Edwards)

As a means of putting further pressure on the British state, the IRA took its war abroad, to military garrisons in Germany, the Netherlands and Gibraltar. In 1987 the IRA shot and killed an RAF serviceman in Roermond, near the German–Dutch border. Half an hour later the IRA blew up a car outside a nightclub in the village of Nieuwbergen, killing two RAF servicemen. In a statement released to the BBC, the IRA said ‘[w]e have a simple statement for Mrs Thatcher: Disengage from Ireland and there will be peace. If not, there will be no haven for your military personnel, and you will regularly be at airports awaiting your dead.’ The IRA had now opened up a new front in their campaign of terror.

In perhaps one of the most controversial episodes in the Troubles, three IRA volunteers were killed by the SAS in Gibraltar on 6 March 1988. Although they had been unarmed at the time they were shot, intelligence suggested that the IRA suspects were preparing a car bomb aimed at British military personnel taking part in a parade. It had striking similarities with the Hyde Park outrage a number of years earlier. The ‘Gibraltar Three’, as they were later known, became martyrs for the Republican cause, and their deaths led to an outpouring of sympathy for the IRA not only from within Republican communities in Northern Ireland, but in Irish diaspora communities abroad.

RUC officers come under attack in Belfast after the signing of the Anglo-Irish Agreement. Unionists were hostile to the accord because it was brokered between London and Dublin without their consent. (Fred Hoare)

Nationalists and Republicans have always found sympathy and support in the many Irish diaspora communities scattered around the world, from the United States to Australia. The US connection, in particular, has borne both lucrative financial and moral support, as well as a steady flow of weapons. Throughout the Troubles, the British government was at pains to exert political pressure on those in the US who were offering their sympathies and support to violent Republicanism. In a speech to Irish-American corporate businessmen in 1977, the Northern Ireland Secretary of State Roy Mason challenged his audience to reconsider their support for militant Republicanism. ‘It is through machinery, not machine guns; through business not bombs that the people of this great nation can assist the tiny but very deserving area of Northern Ireland to continue along the road to normality and prosperity,’ he said.

That the IRA could command support from Irish diaspora communities abroad allowed those who were arguing for an end to hostilities in the early 1990s to situate their ‘armed struggle’ within the broader international environment. Such thinking was advanced by the IRA in its so-called Tactical Use of Armed Struggle (TUAS) document in the mid-1990s. Placing the Irish Republican struggle in a broader context allowed Gerry Adams and those dedicated to the Sinn Féin ‘peace strategy’ to forge ahead on the political front.

The transition from war to peace in the wake of the 1994 paramilitary ceasefires was by no means a smooth one. Under John Major the British government was insistent on decommissioning prior to entering any form of talks about the future of Northern Ireland. They had appointed US Senator George Mitchell as chairman of the international body on arms decommissioning, which was an integral component of the British and Irish governments’ ‘twin-track’ process to address this outstanding issue. Mitchell was later asked to stay on to chair the all-party talks that had evolved out of the bilateral negotiations between the political parties and both governments. Although the IRA was not formally part of the negotiations that led up to the Belfast Agreement of 10 April 1998, it was represented by Sinn Féin.

Addressing members of the Provisional IRA in 2005, Adams said that he had always ‘defended the right of the IRA to engage in armed struggle,’ doing so on the basis that ‘there was no alternative for those who would not bend the knee, or turn a blind eye to oppression, or for those who wanted a national republic’. However, with the onset of the peace process, he emphasized to them that there was now an ‘alternative’. In his mind, the alternative was ‘by building political support for Republican and democratic objectives across Ireland and by winning support for these goals internationally’. Adams successfully convinced the IRA of the need to create the conditions upon which a peace deal could be made. Within days of his speech the organization had called a halt to its armed campaign, and by September 2005 had decommissioned the last of its weapons.

In the Northern Ireland peace process, a range of international initiatives was tried; some had success, others failed completely. The use of third-party mediators was tried in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. However, in the early days of the Troubles it was thought that Britain could fulfil this role. The British government wished to keep Northern Ireland off the international agenda and used its influence on the UN Security Council to do just that. However, as the descent into chaos continued in the wake of the imposition of direct rule in 1972, this was no longer thought possible. With the signing of the Sunningdale Agreement in 1973 and the Anglo-Irish Agreement in 1985 the British state warmed to the idea of greater intergovernmental co-operation with the Republic of Ireland, particularly in the realm of border security. Although Unionists rejected the Anglo-Irish Agreement, they begrudgingly accepted a more prominent role for the Dublin government by the time of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, once constitutional safeguards had been put in place and enshrined by international law.

Northern Ireland was by no means unique in witnessing a clash between protestors and security forces in the late 1960s, as large-scale demonstrations were common in most European cities including London and Paris. What made the Troubles in Ulster unique, however, was the way in which the violence was portrayed as indelibly ethnic or tribal, and somewhat out of sync with the wider Cold War political confrontation between West and East. This caricature of Northern Ireland being ‘a place apart’ has since been challenged, particularly as ethnic-identity disputes exploded after the end of the Cold War in 1991.