Liberals don’t talk about it much, but making health care a “human right” comes with a big downside.

To make health care a human right, as Sen. Bernie Sanders frequently claims a single-payer system will do, the federal government will have to define that right. And by defining what health care individuals will receive, a single-payer system—especially one that prohibits private insurance outside the government system, as the House and Senate bills do—will also define what care individuals will not receive.

As we have seen, by making health care a “human right,” a single-payer system will lead to large increases in people using health care. The combination of 1) more insured patients, 2) more covered services, and 3) the abolition of cost-sharing for all health care services will cause demand to soar.

How, then, can government accommodate all this new demand? In a word, it won’t. Instead, government bureaucrats will attempt to contain health care costs by restricting the supply of care provided.

That rationing will take on several forms. In some cases, physicians will quit, or never enter medical school in the first place, reducing the available supply of care. In other cases, the global budget model introduced in the House’s single-payer bill will encourage hospitals to stint on care to meet their government-set spending targets. In other cases, the government could outright deny treatments federal bureaucrats deem too expensive.

In all cases, however, the limits on access to care will have very real consequences for patients, particularly elderly seniors with multiple chronic conditions. When coupled with the bill’s provisions on abortion, which allow for taxpayer-funded abortion-on-demand, single payer will end up abandoning some of our society’s most vulnerable individuals.

Even single-payer supporters admit their legislation will ration health care.1 When the Mercatus Center released its study questioning the costs of a single-payer system, a writer for the socialist magazine Jacobin responded:

[The study] assumes utilization of health services will increase by 11 percent, but aggregate health service utilization is ultimately dependent on the capacity to provide services, meaning utilization could hit a hard limit below the level [the study] projects.2

This socialist commentator knows of which he speaks. Both the liberal Urban Institute and Rand Corporation assume that demand for health care will increase under a single-payer system, raising health-care spending—but that constraints on supply will prevent many people from accessing all the additional care they seek.3

It seems little surprise, then, that Sanders’s rhetoric about single payer notwithstanding, neither the House nor the Senate single-payer bills actually make health care a right.4 Instead of guaranteeing the right to receive health care, they only guarantee the right to have that care paid for if Americans can find someone to provide it in the first place—a major catch Sanders never mentions.5

Sanders must rely on this legal sleight-of-hand to sell his plan. He, like other single-payer supporters, recognizes that the plan will limit the health care provided to Americans, because supply in the system won’t keep up with demand. Here’s how they will do it.

The claim that moving to a single-payer system will reduce health-care costs comes down to a single premise: That doctors and hospitals will accept less pay to provide more health care to more patients.6 If one disagrees with that premise—and logic suggests that most rational individuals would—then single payer will either lead to an explosion of health-care spending, or a reduction in the supply of care provided.

The current pricing system suggests the latter outcome will occur—namely, that doctors will decide to stop providing care, and may leave the profession entirely. Analysis from the office of the independent, non-partisan Medicare actuary explains why.

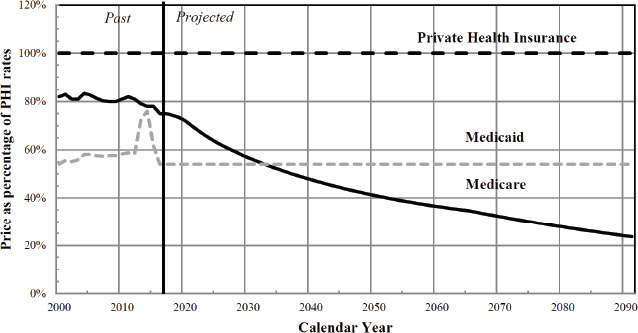

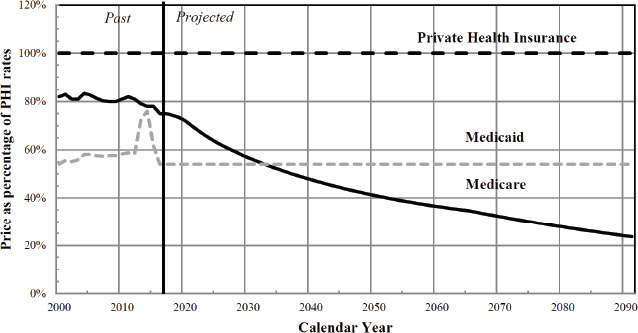

The actuary’s office estimates that as of 2017, Medicare reimbursed physicians at an average of 75% of what private insurance pays them, and as of 2016, Medicaid paid physicians an average of 54% of private rates.7 The actuary also believes that, under current law, Medicare payment rates will continue to fall over time, such that by 2092, Medicare will pay physicians only about 24%—less than one-quarter—of private insurance rates.8

Figure 2. Illustrative comparison of relative Medicare, Medicaid, and private health insurance prices for physician services under current law

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Office of the Actuary, April 2019.

The single-payer bills would cut physician payment significantly, by applying Medicare’s current reimbursement levels to the entire American population. Medicare does pay physicians more than Medicaid does, meaning physicians who treat large numbers of Medicaid patients might see no change in pay, or even a slight increase.

But many more individuals hold private coverage—181 million with employer-sponsored coverage, compared to only about 72 million in Medicaid—meaning that most physicians will see their pay cut under a single-payer system.9 And remember: This pay cut will come at a time when demand for medical services will increase—due to the number of newly covered individuals, and the elimination of virtually all deductibles, co-payments, and other forms of cost-sharing.

Single-payer supporters argue that other nations’ physicians earn much lower salaries, so the added spending on doctors in the United States represents “waste.” Indeed, American physicians, particularly specialists, receive higher pay compared to many of their international peers. As of 2018, American physician salaries averaged $299,000, with the average specialist ($329,000) earning more than the average primary care physician ($223,000).10 These salaries sound quite large to many Americans in absolute terms, and may look generous in the context of a 2011 survey that found doctors in six other developed countries earn anywhere from 35-86% of the salaries of their American peers.11

However, American physicians also carry very high loads of student debt needed to fund their education. In 2018, nearly three-quarters (72.3%) of graduating physicians said they used student loans to pay for medical school.12 Of those who took on debt, the median medical school loan—that is, the 50th percentile—stood at $195,000.13

In other words, more than one-third (36.2%, or half of 72.3%) of graduating medical school students hold at least $200,000 in medical school debt, a sum that excludes loans from their undergraduate work and any other debt, such as a mortgage. Having taken on massive amounts of debt to join the medical profession, many doctors face burnout and fatigue once they do so.

Multiple surveys show high levels of frustration among physicians, in large part due to administrative hassles and bureaucracy. A 2018 survey found that nearly half (48%) of all physicians have considered leaving the profession due to their frustration.14 While single-payer supporters blame private insurance companies for causing doctors’ stress, doctors also believe that government policies (91%) contribute to rising health-care costs almost as much as they believe insurers do (95%).15 Moreover, physicians’ biggest problem with insurance companies—“overrid[ing] the professional judgement of physicians”—would not disappear under a single-payer system. In fact, it would likely get worse.16

The increasing care the United States’ aging population needs, coupled with the retiring wave of doctors in the Baby Boom generation, means the nation’s health system already faces a major physician shortage. Over the course of the next decade—between now and 2030—the United States faces an estimated shortfall of up to 121,300 physicians nationwide.17 With the supply of available physicians already not meeting expected demand, single payer would cause demand for health care to explode, even as it constricts physicians’ availability.

Single payer would exacerbate the forthcoming doctor shortage, reducing the available supply of care by driving physicians out of medicine. For doctors approaching retirement, the rapid changes envisioned by a new system, coupled with the steep pay cuts, would encourage them to hang up their proverbial spurs early. For mid-career physicians, the thought of performing more work for less pay could prompt them to leave the profession. And the prospect of permanently lower wages and high student debt could discourage some interested students from ever entering medical school.

Liberals like to believe that physicians will not respond to changing incentives, but low reimbursements have consequences on patients that single-payer supporters find highly inconvenient. Consider this article from a small newspaper from more than two decades ago:

Dr. Judith Steinberg told her patients in a letter that Community Health Plan/Kaiser Permanente has cut payments to her practice while raising rates to its insured. The decision by Steinberg’s group practice means several hundred patients in CHP’s commercial and its “Access Plus” Medicaid plan will be obliged to either switch doctors or switch insurers. The practice is the only CHP primary care provider in Shelburne.18

The article sounds innocuous enough, until one finds out the identity of Steinberg’s husband: Gov. Howard Dean, like Sanders, a Vermont resident and a very public supporter of single-payer health care. To put it another way, Dean’s wife dropped out of Vermont’s largest Medicaid managed care plan because of its incredibly low reimbursement rates while Dean was governor, and in charge of the Medicaid program. That fact should quite literally bring home to single-payer supporters like Dean and Sanders that doctors could leave the profession in droves should this socialistic scheme come to fruition.

If patients have an insurance card, but no access to medical professionals who will treat them, their “coverage” will prove meaningless. One former head of a state Medicaid program—which in many states provides notoriously stingy payment rates to doctors—called a Medicaid card a “hunting license [that gives patients] a chance to go try to find a doctor” who will see them.19 By encouraging doctors to leave the profession, single payer could leave most Americans with nothing more than a hunting license for medical care.

The Senate’s single-payer bill would apply the existing Medicare fee schedule to hospitals as well as physicians.20 As with the physician analysis above, applying Medicare reimbursement levels to all hospital patients would devastate facilities’ finances. As we have seen, one study found that such a proposal would, for a hypothetical small hospital system, lead to a $330 million cut in revenues each year, and reduce margins from a surplus of 2.3% to a loss of 22.1%.21

However, the House’s most recent version of single-payer legislation proposed a new way of paying hospitals, and a new way for the federal government to stint on patient care.

Under the House legislation, hospitals, along with groups of doctors who elect to opt in to the new system, would receive quarterly, lump-sum reimbursements as “payment in full for all operating expenses for items and services furnished under this Act, whether inpatient or outpatient.”22 The House bill requires each regional director for the new single-payer system to “negotiate” these quarterly payment amounts with hospital providers, based on the following payment factors:

The regional directors will, after considering the factors above, determine the level of hospitals’ lump-sum quarterly payments. Because the government system will cover practically all services, and because any hospital that accepts payments from the government system cannot contract with patients outside of the government system, the regional director’s assessment will, for all intents and purposes, set hospitals’ operating budgets each quarter.24

The process envisioned under the House bill provides tremendous authority to the regional directors, and to HHS as a whole. The bill allows for the HHS secretary to set the number of regions and appoint the regional directors.25 While the current head of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) must receive Senate confirmation, the bill denies the Senate any ability to provide “advice and consent” over the regional directors—even though these officials would effectively set the budgets for all the hospitals in their assigned areas.26 Nor does the bill provide any ability for hospitals to appeal the regional director’s determination, should a hospital consider their quarterly payment amounts inaccurate or insufficient.

Supporters of single payer would argue that providing hospitals with global payments will encourage efficiencies, by requiring them to stick within a defined budget. But the idea that the federal government can set accurate budgets for thousands of hospitals nationwide seems fanciful at best, and dangerous at worst. If the federal government does not set accurate budget levels, and some hospitals end up under-funded, they will likely have to deny patients care. As the next chapter will explain in greater detail, paltry global budget payments in Great Britain have resulted in “severe financial strains” for that country’s National Health Service, with tens of thousands of operations canceled and massive delays, even for emergency care.27

Two provisions in the House bill suggest that its authors intend to save costs by restricting the supply of care. In discussing payments to hospitals, the House bill prohibits hospitals from using “operating expenses and funds” to finance “a capital project funded by charitable donations,” without the express approval of the regional director.28 In other words, hospitals may not use federal dollars to operate new parts of the hospital that they build and pay for themselves—using charitable contributions rather than capital expenses provided by the government system. This restriction indicates how much single-payer proponents want to ration health care by restricting its supply.

Surprisingly, the House’s single-payer bill also concedes that the new system will not lead to better-quality care. The bill prohibits HHS from “utiliz[ing] any quality metrics or standards for the purposes of establishing provider payment methodologies…under this title.”29 Think about that for a moment: The bill actually prohibits the federal government from paying good doctors and hospitals more than bad ones.

Mind you, conservatives might argue that the government cannot effectively determine the “best” care, and that those decisions belong in the hands of patients. But they would agree that “good” doctors and hospitals, however defined, should receive more pay than bad ones. The House single-payer bill explicitly rejects that principle, making its other provisions on quality standards effectively moot. And because quality metrics do not matter to hospitals’ pay, the global budgets will give them every incentive to pinch pennies by denying care.

Among the biggest proponents of the global budgets included in the House’s single-payer bill: Donald Berwick, administrator at CMS following the passage of Obamacare. Berwick—infamous for his comments about “rationing with our eyes open”—also advocated for capping total spending on health care.30 In journal articles, he promoted “global caps on health care spending,” ideally through a single-payer system.31

Berwick’s writings provide rich insights into the thinking of his fellow single-payer proponents. He envisions a centralized system run by technocrats, whom he believes will make efficient decisions about where and how to allocate resources. It sounds well and good until the implications of this type of system become apparent.

First, Berwick would sharply limit the supply of health care available—which, in his mind, represents perhaps the only way to control rising costs. In 1993, he wrote that most cities “should reduce the number of centers engaging in cardiac surgery, high-risk obstetrics, neonatal intensive care, organ transplantation, tertiary cancer care, high-level trauma care, and high-technology imaging.”32

Most people would find the idea of shutting down cancer centers and neonatal intensive care units offensive and scary, in case they or a loved one might need them. For instance, had policy-makers followed Berwick’s advice a quarter-century ago, and shut down neonatal intensive care units, babies born with opioid withdrawal symptoms during our nation’s current crisis with that drug might have faced even tougher odds. But Berwick apparently believes that he and his fellow technocrats can better manage care for the American people than doctors and patients can.

Of course, limiting the supply of health care also implies that government bureaucrats can determine the “correct” amount of care to provide—no more, no less. Berwick believes passionately in such an outcome: “I want to see that in the city of San Diego or Seattle there are exactly as many MRI units as needed when operating at full capacity. Not less and not more.”33 Over and above the important question of whether the government should have the power to determine the “correct” number of MRI units in San Diego or Seattle, it’s not at all clear that government could determine that number with any level of accuracy or consistency.

Second, Berwick believes that, in at least some cases, doctors should fail to treat their individual patients’ needs if doing so would harm the “collective good.” In 1999, he and several colleagues signed a declaration calling on their fellow physicians not to “manipulate”—their exact words—the system to help individual patients:

Limited resources require decisions about who will have access to care and the extent of their coverage. The complexity and cost of healthcare delivery systems may set up a tension between what is good for the society as a whole and what is best for an individual patient.…Those working in health care delivery may be faced with situations in which it seems that the best course is to manipulate the flawed system for the benefit of a specific patient or segment of the population, rather than to work to improve the delivery of care for all. Such manipulation produces more flaws, and the downward spiral continues.34

By specifically using the term “manipulate” to refer to doctors who try to help their individual patients, Berwick makes clear his view that, with costly care, individuals must sacrifice their wishes and desires to the will of the collective—which to liberals means the will of the government.

The president for whom Berwick worked has also acknowledged that government may need to limit access to costly medical treatments. Barack Obama waited until after Congress had enacted Obamacare before nominating the controversial Berwick to the CMS administrator post.35 But in a 2009 interview with the New York Times, Obama, while acknowledging the human costs of such policies, implied that at some point, government would have to limit access to treatments:

The chronically ill and those toward the end of their lives are accounting for potentially 80 percent of the total health care bill out here….There is going to have to be a conversation that is guided by doctors, scientists, ethicists. And then there is going to have to be a very difficult democratic conversation that takes place.36

Approximately two months after that interview, at a televised event on health care held at the White House, Obama spoke with Jean Sturm, the daughter of a patient who received a pacemaker at age 100. When Sturm asked Obama about how he might determine access to care for the elderly, Obama first discussed how “we as a culture and as a society [should start] to make better decisions.”

But then he talked about “waste in the system,” culminating in the following: “We can let doctors know and your mom know that, you know what? Maybe this isn’t going to help. Maybe you’re better off not having the surgery, but taking the painkiller.”37

Other appointees in the Obama administration came up with their own theories for making difficult decisions about access to treatments. In 2009, Zeke Emanuel—brother of Rahm, and an advisor in the Office of Management and Budget during the debate on Obamacare—wrote an article entitled “Principles for Allocation of Scarce Medical Interventions,” that included the following chart demonstrating his theory:

Zeke Emanuel et al., The Lancet, January 2009. Reprinted with permission.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then this chart certainly speaks volumes.38

In that same article, Emanuel articulated the principles behind the same debate Berwick and Obama engaged in, on how to allocate scarce medical resources:

Adolescents have received substantial education and parental care, investments that will be wasted without a complete life. Infants, by contrast, have not yet received these investments…. The complete lives system discriminates against older people…. [However,] age, like income, is a “non-medical criterion” inappropriate for allocation of medical resources.

Emanuel admitted that decisions to allocate scarce medical resources will, almost by definition, discriminate against the most vulnerable in society—the very young and the very old.

If those quotes do not give one pause, consider another quote by Zeke Emanuel, this one from a 1996 work: “[Health care] services provided to individuals who are irreversibly prevented from being or becoming participating citizens are not basic and should not be guaranteed. An obvious example is not guaranteeing health services to patients with dementia.”39 When that quote resurfaced during the debate on Obamacare in 2009, Emanuel attempted to claim he had never actually advocated for this position, but he wrote the words nonetheless.40

Unfortunately, as Sturm recognized during the June 2009 town hall with President Obama, setting hard-and-fast rules about access to care—as she termed it, “a medical cut-off at a certain age”—means someone almost certainly will suffer in the exchange. Even if the federal government can make “good” (i.e., medically accurate) decisions about what care to provide, and not provide, the average patient, a single patient by definition is not average.

In many cases, for example, drug and device manufacturers find it difficult to test their products for pediatric use because developing bodies process drugs differently than adults do, and because so few young people need to use devices like pacemakers.41 Likewise, many clinical trials have historically under-represented key populations, such as women, particularly pregnant women, and racial minorities. Genomic trials continue to under-represent such patients today.42 A drug or treatment that works poorly for most of the population could work incredibly well for certain individuals, or important sub-populations—but only if researchers have that information readily available and are willing to put it into practice.

If bureaucrats make coverage decisions based on the response of the “average” patient, then populations under-represented in research could especially suffer.

Creating blanket, one-size-fits-all coverage rules would impede access to these treatments for those who need, or could benefit from, them most. As with most well-intentioned government interventions, the people the Left claims they most want to help—vulnerable populations, with little access to clinical trials, and few resources to pay for costly treatments out of their own pockets—may well end up suffering the greatest harm.

In addition to restricting care for vulnerable patients with expensive health conditions, single payer also jeopardizes the rights of the unborn. Both the House and Senate bills include a provision stating that “any other provision of law in effect on the date of enactment of this Act restricting the use of federal funds for any reproductive health service shall not apply” to the single-payer system.43

This provision would effectively ensure that the Hyde Amendment’s restrictions on taxpayer funding of abortion would not apply to the single-payer system. Former Congressman Henry Hyde (R-IL) helped enact the eponymous provision in 1976; Congress has included the language in its annual spending bills every year since then. In its current form, the Hyde Amendment prevents taxpayer funding of abortion, except in cases of rape, incest, or to save the life of the mother.44

Just a few years ago, Democrats said they wanted to ensure no taxpayer dollars funded abortion coverage. In his address to Congress in September 2009, Obama claimed that “under our plan, no federal dollars will be used to fund abortions.”45 Two months later, 64 Democratic members of Congress voted to put Obama’s claim into practice, supporting an amendment offered by Rep. Bart Stupak (D-MI) that would have prevented any Obamacare insurance plan from offering coverage for elective abortions—that is, abortions outside the Hyde Amendment’s three stated exceptions (rape, incest, and to save the life of the mother).46

Unfortunately, the version of Obamacare enacted into law did not include the Stupak amendment’s life protections. Instead, Democrats constructed a segregation mechanism, whereby taxpayer dollars could still flow to insurance plans that cover abortion, so long as insurers could supposedly keep the abortion dollars “separate.”47 Pro-life groups rightly exposed this mechanism as an accounting gimmick, due to money’s inherent fungibility.48 Government auditors also said the Obama administration failed to implement even these minimal restrictions on abortion funding.49

But at least Democrats felt the need to claim they opposed taxpayer funding of abortion, even if their proposals did not fulfill their rhetoric. No more. The left wing of the party is now pushing for a vote to abolish the Hyde Amendment, to allow for taxpayer funding of abortion at any time in a pregnancy and for any reason.50

The language in the single-payer bill, which would prevent the Hyde Amendment’s restrictions from applying to the new government program, merely reflects the party’s movement ever leftward. It also would allow abortion for many weeks during which the unborn child could be saved through a C-section, an allowance large and bipartisan majorities of Americans oppose.

Likewise, nothing in either the House or the Senate bills prohibits the federal government, and HHS, from paying for euthanasia through the single-payer program. With eight states now having authorized “aid in dying,” a future administration could easily rule that such means constitute “medically… appropriate” action for “treatment…of a health condition.”51

In fact, both bills require HHS to use “new information from medical research” and “other relevant developments in health science” to update the list of covered benefits.52 If more states authorize euthanasia, the case for paying for it through single-payer would only grow, especially as a cost-saving measure given the massive costs of end-of-life care.

A culture that encourages euthanasia places a premium on the collective—as determined by government bureaucrats—over preserving each and every life, no matter how vulnerable, and especially when vulnerable. In this context, Berwick’s comments prove most revealing, as they illustrate how liberals believe physicians should not “manipulate” the system to ensure a single specific patient benefits.

That philosophy explains how single-payer systems contain costs: by limiting the supply of care in general, and denying access to costly care in particular. An examination of single-payer systems overseas demonstrates how patients often wait—and wait, and wait some more—for care, and in some cases never receive it at all.

1 Chris Jacobs, “Bernie Sanders Supporters Admit His Socialized Medicine Plan Will Ration Care,” The Federalist August 2, 2018, http://thefederalist.com/2018/08/02/bernie-sanders-supporters-admit-socialized-medicine-plan-will-ration-care/.

2 Matt Bruenig, “Even Libertarians Admit Medicare for All Would Save Trillions,” Jacobin, July 30, 2018, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2018/07/medicare-for-allmercatus-center-report.

3 John Holahan, et al., “The Sanders Single Payer Health Care Plan: The Effect on National Health Expenditures and Federal and State Spending,” Urban Institute, May 9, 2016, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/80486/200785-The-Sanders-Single-Payer-Health-Care-Plan.pdf; Jodi Liu and Christine Eibner, “National Health Spending Estimates Under Medicare for All,” Rand Corporation, April 2019, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR3106.html.

4 Chris Jacobs, “Why Single Payer Wouldn’t Get Americans More Health Care,” Federalist, April 11, 2019, https://thefederalist.com/2019/04/11/single-payer-wouldnt-get-americans-health-care/.

5 See for instance Section 201(a) of H.R. 1384 and S. 1129, the Medicare for All Act of 2019.

6 Jacobs, “Sanders Supporters Admit.”

7 John Shatto and Kent Clemens, “Projected Medicare Expenditures under an Illustrative Scenario with Alternative Payment Updates to Medicare Providers,” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Office of the Actuary memorandum, April 22, 2019, https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/ReportsTrustFunds/Downloads/2019TRAlternativeScenario.pdf, p. 7.

8 Ibid.

9 Edward Berchick, Emily Hood, and Jessica Barnett, “Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2017,” Census Bureau Report P60-264, September 2018, https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2018/demo/p60-264.pdf, Table 1, Coverage Numbers and Rates by Type of Health Insurance: 2013, 2016, and 2017, p. 4; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “December 2018 Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment Data Highlights,” https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/medicaid-and-chip-enrollment-data/report-highlights/index.html.

10 Leslie Kane, “Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2018,” https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2018-compensation-overview-6009667#2.

11 Miriam Laugesen and Sherry Glied, “Higher Fees Paid to U.S. Physicians Drive Higher Spending for Physician Services Compared to Other Countries,” Health Affairs, September 2011, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0204.

12 Association of American Medical Colleges, “Medical School Graduation Questionnaire: 2018 All Schools Summary Report,” July 2018, https://www.aamc.org/download/490454/data/2018gqallschoolssummaryreport.pdf, p. 44.

13 Ibid.

14 Alliance for the Adoption of Innovations of Medicine, “Putting Profits Before Patients: Provider Perspectives on Health Insurance Barriers that Harm Patients,” October 2018, https://aimedalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Aimed-Alliance-Primary-Care-Survey-Report.pdf, p. 18.

15 Ibid., p. 10.

16 Ibid., p. 11.

17 IHS Markit, “The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2016 to 2030,” Report for the American Association of Medical Colleges, March 2018, https://aamc-black.global.ssl.fastly.net/production/media/filer_public/85/d7/85d7b689-f417-4ef0-97fb-ecc129836829/aamc_2018_workforce_projections_update_april_11_2018.pdf.

18 Associated Press, “Governor’s Wife Cuts Ties with HMO,” Rutland (VT) Herald, May 17, 1998.

19 Comments by DeAnn Friedholm at “Affordability and Health Reform: If We Mandate, Will They (And Can They) Pay?” Alliance for Health Reform briefing, November 20, 2009, http://www.allhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/TranscriptFINAL-1685.pdf, p. 40.

20 Section 611(a) of S. 1129.

21 Jeff Goldsmith, Jeff Leibach, and Kurt Eicher, “Medicare Expansion: A Preliminary Analysis of Hospital Financial Impacts,” Navigant Consulting, March 2019, https://www.navigant.com/-/media/www/site/insights/healthcare/2019/medicare-expansion-analysis.pdf.

22 Section 611(a)(1) of H.R. 1384.

23 Section 611(b)(2) of H.R. 1384.

24 Section 301(b)(1) of H.R. 1384.

25 Section 403 of H.R. 1384.

26 Section 403(b)(1) of H.R. 1384.

27 Congressional Budget Office, “Key Design Components and Considerations for Establishing a Single Payer Health Care System,” May 1, 2019, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2019-05/55150-singlepayer.pdf, p. 26.

28 Section 614(c)(4) of H.R. 1384.

29 Section 614(f) of H.R. 1384.

30 “Rethinking Comparative Effectiveness Research,” An Interview with Dr. Donald Berwick, Biotechnology Healthcare, June 2009, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2799075/pdf/bth06_2p035.pdf.

31 Donald Berwick, Thomas Nolan, and John Whittington, “The Triple Aim: Care, Health, and Cost,” Health Affairs, May/June 2008, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/pdf/10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759.

32 Donald M. Berwick, “Buckling Down to Change,” speech to 5th annual National Forum on Quality Improvement in Health Care, December 1993, in Berwick, Escape Fire: Designs for the Future of Health Care (Jossey-Bass, 2004), pp. 28-29.

33 “QMHC Interview: Donald M. Berwick, MD,” Quality Management in Health Care (Fall 1993): 76.

34 Richard Smith, Howard Hiatt, and Donald Berwick, “A Shared Statement of Ethical Principles,” BMJ, January 23, 1999, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1114728/.

35 Berwick’s nomination still proved so contentious that Democrats refused to bring him up for a confirmation vote, despite controlling 59 seats in the Senate.

36 David Leonhardt, “After the Great Recession,” New York Times, April 28, 2009, https://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/03/magazine/03Obama-t.html.

37 “Obama’s Health Future,” Wall Street Journal, June 29, 2009, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB124597492337757443; video of the exchange available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U-dQfb8WQvo.

38 Govind Persad, Alan Wertheimer, and Ezekiel Emanuel, “Principles for Allocation of Scarce Medical Interventions,” Lancet, January 31, 2009, https://www.scribd.com/document/18280675/Principles-for-Allocation-of-Scarce-Medical-Interventions.

39 Ezekiel Emanuel, “Where Civic Republicanism and Deliberative Democracy Meet,” Hastings Center Report, November/December 1996, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3528746.

40 D’Angelo Gore, “Deadly Doctor?” FactCheck.Org, August 14, 2009, https://www.factcheck.org/2009/08/deadly-doctor/.

41 Chris Jacobs, “Dad of Sick Child Explains Why Single Payer Always Leads to Rationing,” Federalist, March 6, 2009, http://thefederalist.com/2019/03/06/dad-sick-child-explains-single-payer-always-leads-rationing/.

42 Katherine Liu and Natalie Dipietro Mager, “Women’s Involvement in Clinical Trials: Historical Perspective and Future Implications,” Pharmacy Practice, January-March 2016, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4800017/; “Report of the Task Force on Research Specific to Pregnant Women and Lactating Women,” September 2018, https://www.nichd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2018-09/PRGLAC_Report.pdf; Caroline Chen and Riley Wong, “Black Patients Miss Out on Promising Cancer Drugs,” ProPublica, September 19, 2018, https://www.propublica.org/article/black-patients-miss-out-on-promising-cancer-drugs; Jonathan Lambert, “Human Genomics Research Has a Diversity Problem,” NPR, March 21, 2019, https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/03/21/705460986/human-genomics-research-has-a-diversity-problem.

43 Section 701(b)(3) of H.R. 1384 and S. 1129.

44 Jon Shimabukuro, “Abortion: Judicial History and Legislative Response,” Congressional Research Service Report RL33467, December 7, 2018, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL33467.pdf.

45 Barack Obama, Speech to a Joint Session of Congress, September 9, 2009, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/transcript-obamas-health-care-speech/.

46 House Amendment 509 to H.R. 3962 (111th Congress); House Roll Call Vote 884 of 2009, http://clerk.house.gov/evs/2009/roll884.xml.

47 Section 1303(b)(2) of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, P.L. 111-148, codified at 42 U.S.C. 18023(b)(2).

48 Arina Grossu, “Abortion Funding and Obamacare,” Family Research Council Issue Analysis IS14F01, September 2016, https://downloads.frc.org/EF/EF14F35.pdf.

49 Government Accountability Office, “Coverage of Non-Excepted Abortion Services by Qualified Health Plans,” Report GAO-13-742R, September 15, 2014, https://www.gao.gov/assets/670/665800.pdf.

50 H.R. 1692 and S. 758, Equal Access to Abortion Coverage in Health Insurance Act; Jessie Hellmann, “House Dems to Push Pelosi for Vote on Bill That Would Allow Federal Funding of Abortion,” The Hill, March 12, 2019, https://thehill.com/policy/healthcare/433700-house-dems-to-push-pelosi-for-vote-on-bill-that-would-allow-federal-funding.

51 Sam Sutton, “Murphy Signs Aid in Dying Bill into Law,” Politico April 12, 2019, https://www.politico.com/states/new-jersey/story/2019/04/12/murphy-signs-aid-in-dying-bill-into-law-966815; Section 201(a) of H.R. 1384 and S. 1129.

52 Section 201(b) of H.R. 1384 and S. 1129.