On April 18, 2009, Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D-IL) spoke at a health-care rally in Chicago. A member of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, which has primary congressional jurisdiction over health care, Schakowsky told the crowd of liberal activists she supported their goal of a single-payer health-care system:

I know that many of you here today are single payer advocates [loud cheering], and so am I. I’m a cosponsor of [H.R.] 676 [a single-payer bill]. And those of us who are pushing for a public health insurance option don’t disagree with the goal. This is not a principled fight. This is a fight about strategy for getting there—and I believe we will.1

She explained that creating a government-run health plan, or a “public option,” would lead to single-payer advocates’ ultimate goal, recounting events at the White House’s health-care summit a few weeks previously:

And next to me was a guy from the insurance company, who then argued against the public health insurance option, saying it wouldn’t let private insurance compete—that a public option will put the private insurance industry out of business and lead to single payer. [Loud cheering.] My single-payer friends, he was right! The man was right!2

Schakowsky’s comments illustrate the problems with the supposed “incremental” strategies Democrats advocate to the general public. Lumped into a broad category of “Medicare for More,” these proposals would try to expand the number of individuals on government coverage (whether Medicare, Medicaid, or both) while retaining some role for private insurance—at least in the short term.

But Schakowsky’s comments show that, at their core, most liberal policy-makers don’t believe in giving patients choice in health care, or in the power of competition to provide better-quality care. Schakowsky doesn’t just think that a government-run health plan will lead to single payer. Her comments very clearly indicate that she wants to bring about such an outcome.

Liberals view the number of people with private insurance as a political problem to overcome. They want to get to single payer, but they recognize that throwing more than 180 million Americans off of employer-sponsored coverage presents an obstacle to objective. These policy-makers don’t actually believe in the private provision of health coverage, but will include some short-term nods in that direction, largely to appease public opinion.

Take for instance Jacob Hacker, the Yale University professor who helped popularize the concept of a government-run “public option” for health insurance.3 At a July 2008 policy forum, Hacker explained that he, like Schakowsky, wants to end up with a single-payer system, and thinks a government-run plan will lead to such an outcome:

Someone once said to me this is a Trojan horse for single payer. And I said, “Well, it’s not a Trojan horse, right? It’s just right there!” I’m telling you—we’re going to get there. Over time, slowly, but we’ll move away from reliance on employment-based health insurance—as we should—but we’ll do it in a way that we’re not going to frighten people into thinking they’re going to lose their private insurance.4

Note the contradictory nature of Hacker’s comments: He does not want to “frighten people into thinking they’re going to lose their private insurance,” even though he thinks “we’re going to get” to a single-payer system—which involves people losing their private insurance.

The fact that advocates of a government-run health plan want these various “incremental” proposals to lead to single payer demonstrates precisely why they should concern American patients. Despite claims that a government-run plan will compete on a “level playing field” with private coverage, Schakowsky, Hacker, and the like will design policies to put a thumb—more like a fist—firmly on the scale in favor of the government plan. Over time, and likely sooner rather than later, the government-run “option” will become the only “option” people have, putting the United States on the expressway to single-payer health care.

Democrats have introduced many pieces of legislation to revise or expand Obamacare’s subsidy scheme, expand government-run health coverage, or some combination of the two.5 Essentially, these bills would make health care more “affordable” by expanding government price controls, using Americans’ hard-earned taxpayer dollars to subsidize coverage for some portion of the population, or both. Noteworthy proposals in these categories include the following:

Sen. Debbie Stabenow (D-MI) introduced this legislation as S. 470, the Medicare at 50 Act.6 Under the bill, individuals could buy into the Medicare program, including Medicare Advantage, once they turn 50. Enrollees would pay a monthly premium, equal to the full cost of providing Medicare benefits for the eligible population (i.e., people ages 50-64).

While the federal government pays for 75% of Medicare beneficiaries’ Part B premiums, enrollees in the buy-in program would not automatically receive a government subsidy. However, individuals who qualify for Obamacare insurance subsidies—those without an offer of “affordable” employer coverage, and with family incomes below 400% of the federal poverty level ($103,000 for a family of four in 2019)—could use those subsidies to defray their premiums for the Medicare buy-in program.

In the House, Rep. Brian Higgins (D-NY) has introduced similar legislation as H.R. 1346. In addition to the Medicare buy-in for individuals over 50, the Higgins bill also includes “stabilization” provisions for Obamacare exchanges. These “stability” provisions would reinstate federal programs of reinsurance—subsidizing insurers for some of the expenses high-cost patients incur—and risk corridors—reimbursing insurance plans with large losses, offset (in whole or in part) by payments to the federal government from plans with large profits—that under Obamacare expired in 2016.7 The bill would also provide increased cost-sharing assistance (i.e., lower deductibles and co-payments) for households with incomes lower than 400% of the federal poverty level.

These proposals also allow individuals to buy into the Medicare program. However, unlike the Stabenow and Higgins bills—which limit the buy-in to individuals over 50—these bills permit individuals of any age to purchase Medicare coverage. These proposals more closely resemble the government-run “public option” that Democrats proposed, but rejected, while debating Obamacare in 2009-10.

Sen. Tim Kaine (D-VA) and declared 2020 presidential candidate Sen. Michael Bennet (D-CO) have introduced one version of this proposal, S. 981, the Medicare-X Choice Act. The bill would make a government-run health plan available to individuals on the Obamacare exchanges. The plan would phase in over several years, beginning in 2021 in areas with no choice of insurer on their exchanges. By 2024, the plan would extend to the nationwide individual health insurance market, and in 2025 would extend to small business coverage.

Under the Medicare-X Choice Act, the government-run plan would reimburse doctors and hospitals at Medicare rates; however, the secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) could increase those rates “by up to 25 percent” for items and services furnished in rural areas. Medical providers would be required to participate in the plan in order to participate in Medicare and Medicaid. The legislation would also reinstate a reinsurance mechanism for the Obamacare exchanges, and increase the Obamacare subsidy regime, removing the income cap on eligibility (currently set at 400% of the poverty level, or $103,000 for a family of four in 2019) and capping premiums at 13% of household income for affluent households (low-income families would pay a smaller percentage of income).

Sens. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) and Sherrod Brown (D-OH) have introduced their own version of this proposal as S. 1033, the CHOICE Act; Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D-IL) introduced a House companion as H.R. 2085. The legislation would establish a government-run health plan on the exchanges, beginning in 2020. The HHS secretary would set premiums for the plan, and “negotiate” with providers regarding their reimbursement levels; however, if the secretary and providers do not agree, reimbursement rates would default to Medicare levels. All doctors and hospitals currently participating in Medicare or Medicaid would be deemed participating in the government-run plan, unless such providers affirmatively opt out.

Sen. Ben Cardin (D-MD) has introduced another version of this proposal, the Keeping Health Insurance Affordable Act, S.3. His legislation would also establish a government-run health plan, available only through the exchanges. The government-run plan would reimburse doctors at Medicare rates for its first three years (2020 through 2022). For 2023 and future years, the HHS secretary would also set rates administratively (i.e., through government fiat), but the new rates could not “increase average medical costs per enrollee” compared to continuing under the Medicare reimbursement formulae.

Doctors currently participating in Medicare would automatically be considered participating in the government-run plan, but could opt out “in a process established by the Secretary.” The legislation would also increase eligibility for Obamacare premium subsidies to households with incomes lower than 600% of poverty ($154,500 for a family of four in 2019; the current limit is $103,000, or 400% of poverty), and includes several provisions related to prescription drug pricing.

Finally, Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-OR) has introduced his own Medicare plan, which he calls Medicare Part E. Under his Choose Medicare Act (S. 1261), the Medicare Part E plan would offer all of Obamacare’s required benefits, including abortion coverage. Any individual could enroll in the plan, except those already eligible for the current Medicare and Medicaid programs. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services would develop a plan to enroll interested employers in the program.

Under the Merkley Medicare Part E plan, the new program would “negotiate” rates with doctors and hospitals. Payments could not total less than the current Medicare program, but could not exceed the average rates paid by insurers on the Obamacare exchanges. The plan would deem providers participating in the current Medicare program participants in the new Medicare Part E, and would prohibit participating providers from balance billing their patients. (To use a hypothetical example, balance billing might occur when a doctor charges $100 for a service, and patient’s insurer reimburses only $50. Under balance billing, a doctor would attempt to charge the patient the $50 difference in reimbursement, plus any co-payment insurance might require.)

The Merkley legislation would appropriate $2 billion to establish Medicare Part E, along with additional funds for program reserves. It includes additional provisions related to the current Medicare program—imposing an out-of-pocket limit on beneficiary cost-sharing, and requiring “negotiation” of prescription drug prices.

In addition, Merkley bill would increase funding for Obamacare in several respects. It would authorize funding for the law’s navigator programs, and appropriate $10 billion per year from 2020 through 2022 ($30 billion total) to fund reinsurance programs in every state. The bill would expand eligibility for Obamacare’s insurance subsidies up to 600% of poverty ($154,500 for a family of four in 2019). The legislation would also link those subsidies to more generous insurance coverage—gold plans, with an actuarial value (the percentage of an average enrollee’s health expenses paid by insurance) of 80%, rather than silver plans, with an actuarial value of 70%. And the bill would further reduce cost-sharing for low-income beneficiaries.

Sen. Brian Schatz (D-HI) has introduced S. 489, which would give states the option to allow individuals to buy into the Medicaid program. For individuals participating in the buy-in program, states could impose “premiums, deductibles, cost-sharing, or other similar charges that are actuarially fair.” However, states could not charge anyone a premium greater than 9.5% of household income, and must abide by Obamacare’s rating restrictions (i.e., vary premiums only by age, family size, geography, and tobacco use).

The Schatz bill also includes provisions designed to encourage recalcitrant states to expand Medicaid to the able-bodied, by providing a 100% federal match for the first three years states take up the expansion. (Under current law, the 100% match for expansion populations applied to calendar years 2014-16 only.) In the House, Rep. Ben Ray Lujan (D-NM) has introduced similar legislation to the Schatz bill as H.R. 1277.

This proposal does not exist as a piece of legislation—at least not yet. Rather, a group of researchers at the liberal Urban Institute fashioned this proposal in 2018, to outline a potential way forward for Democrats on health care.8 Effectively, the plan would retain a role for employer coverage and the current Medicare program, but consolidate most other forms of insurance into a new program.

The plan proposes combining most current Medicaid enrollees and participants on the Obamacare exchanges into a new “super-exchange,” called Healthy America. Individuals could purchase private or publicly offered insurance plans—as in the current Medicare program—but insurance offered through Healthy America would pay doctors and hospitals at Medicare rates, “with some adjustments” possible “to encourage plan availability in all markets.”9

The plan would also increase subsidies for policies offered through Healthy America compared to the current Obamacare subsidies. No household would pay more than 8.5% of its income in premiums, regardless of its income, as opposed to Obamacare, which offers subsidies only to households with incomes less than 400% of poverty ($103,000 for a family of four in 2019).

The plan would retain the current system of employer-sponsored coverage; however, individuals could decline their employer plan and still receive subsidies for Healthy America coverage. (Obamacare contains a “firewall,” such that individuals with an offer of “affordable” employer coverage cannot qualify for exchange subsidies.10) The plan would also reinstitute an individual mandate to purchase health coverage, with an accompanying tax penalty.11

Introduced by Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-CT) as H.R. 2452, this plan has its roots in a proposal offered by the liberal Center for American Progress.12 The bill would create a temporary government-run health plan for the years 2021 and 2022. That plan would pay medical providers Medicare reimbursement rates, and automatically declare any provider participating in Medicare or Medicaid as of the date of enactment a participating provider for the new government-run health plan. The plan would cover the full complement of Obamacare-mandated benefits, including abortion coverage. It would also prohibit providers from failing to perform abortions or other covered services “because of their religious objections.”13

Beginning in 2023, the bill would create the Medicare for America program. The program would automatically enroll individuals at birth, when they become eligible for Medicare (i.e., turn 65), or who lack “qualified health coverage.” By 2025, the bill would incorporate existing Medicare populations into the program, and by 2027, the bill would incorporate existing Medicaid populations into the program. After that time, the only options for “qualified health coverage” outside the program would include qualified employer coverage (including Tricare and the Federal Employees Health Benefit Program), coverage through the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the Indian Health Service.

The bill specifically makes the provision of private health insurance “unlawful,” except for qualified employer coverage. However, unlike the single-payer bills, private insurers could offer Medicare Advantage for America plans as part of the new program (similar to Medicare Advantage today).

The bill prescribes premiums and maximum cost-sharing amounts. Households with incomes less than 200% of poverty ($51,500 for a family of four in 2019) would pay no premiums, while those with incomes greater than 600% of poverty ($154,500 for a family of four in 2019) would pay 8% of their income in premiums. Likewise, households with incomes less than 200% of poverty will pay no cost-sharing at all; those with incomes greater than 600% of poverty will pay no more than $5,000 in total out-of-pocket expenses per family. The bill eliminates all deductibles for Medicare for America plans.

In addition to prohibiting providers from balance billing patients, the bill prohibits any provider “from entering into a private contract with an individual enrolled under Medicare for America for any item or service coverable under Medicare for America.”14 The legislation would automatically enroll Americans in the new program, and would only permit individuals to opt out who have “qualified health coverage” from certain employers.15 Therefore, the ban on private contracting would effectively prohibit most Americans from opting out of the government system. To put it bluntly, this provision would prevent most Americans from obtaining private health care—even with their own money.16

The program would pay doctors and medical providers Medicare or Medicaid rates, whichever is greater, and would pay hospitals 110% of those current Medicare or Medicaid payment levels. All participating providers in Medicare would be deemed providers for the new program. The secretary could also increase rates “to ensure adequate access to care.”

Large employers—those with more than 100 employees—would face a “pay or play” mandate. They could continue to maintain their employer plans, provided their plan covers at least 80% of an average employee’s health expenses and the employer pays at least 70% of premiums. If they do not, they must make a contribution equal to 8% of annual payroll to fund the new program.

Small employers with fewer than 100 employees could continue to maintain their current coverage, but would not face a penalty if they do not. Workers could decline an offer of employer coverage to enroll in the new program without penalty, in which case the employer (regardless of the firm’s size) must make a contribution for the worker’s coverage equal to the firm’s contribution for the worker’s employer-provided coverage.

This bill, unlike the single-payer bills and other pieces of legislation described above, includes explicit tax increases to pay for the new program. Those tax provisions include:

The bill also includes a series of other provisions, including elimination of the 24-month waiting period for individuals with disabilities to qualify for Medicare benefits, an expansion of coverage for long-term services and supports, mandatory nurse staffing requirements for hospitals, and provisions related to prescription drug pricing.

Each of these pieces of legislation would accelerate the march to single payer, on multiple levels. First, and most obviously, they all attempt to “piggyback” on existing reimbursement rates paid by government programs, which pay doctors and hospitals far less than private insurers do.

As we have seen, Medicare currently pays doctors 75% of private insurance rates, and hospitals 60% of private insurance.18 Likewise, Medicaid pays doctors about 54% of private insurance rates, and hospitals about 61%.19 And Medicare and Medicaid payment rates are expected to decline further when compared to private insurance in the coming years, due to scheduled reductions in reimbursement formulae.20

As Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement rates decline, enrollment has increased in these programs—due to the retirement of the Baby Boomers and the expansion of Medicaid under Obamacare, respectively. As more and more people enroll in programs that pay providers less and less, two linked trends have occurred:

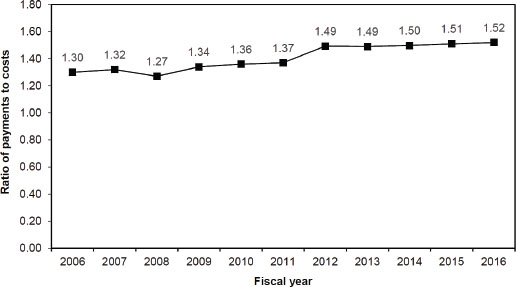

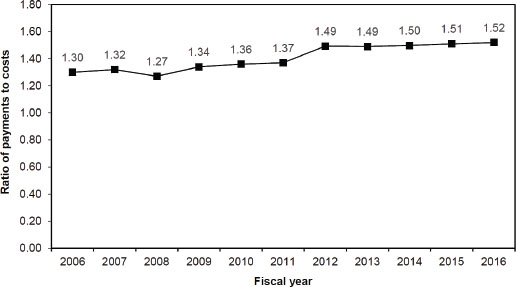

Put more simply, hospitals are charging patients with private insurance more because government programs are paying them less. With hospitals losing sizable sums on Medicare patients—the average hospital had a -9.9% profit margin on Medicare patients in 2017, a loss projected to increase to 11% in 2019—patients with private insurance help to pick up the proverbial slack.22 But what happens when there are fewer people with private insurance to do so?

Chart 6-26. Change in the private-payer ratio of payments to costs for hospital services, 2006-2016

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, June 2018.

Because the government-run plan would use Medicare or Medicaid reimbursement rates that are substantially lower than private health insurance payments, private insurers will have little ability to compete based on price. The government-run plan will offer lower premiums, because it will force hospitals and doctors to accept less pay for their services, siphoning off millions of patients.

In response, medical providers, particularly ones with large market share in uncompetitive markets, may try to raise charges on their privately insured customers, to compensate for the greater losses incurred by patients moving to the government-run health plan. But if they charge patients with private insurance more, that will lead to higher premiums—and more people switching to the government-run health plan. Medical providers would face a no-win situation, and private insurance could easily face a “death spiral,” whereby a cycle of premium increases sends more and more people into the government-run health plan, making it a de facto single-payer system.

During the Obamacare debate in 2009, non-partisan actuaries at the Lewin Group predicted this very phenomenon. Their analysis concluded that a government-run health plan reimbursing providers at Medicare rates would have premiums 26% lower than private coverage for an individual, and 22% lower for a family.23 If such a government-run health plan were open to all individuals, Lewin concluded that 119.1 million Americans—more than half of those with employer-based health coverage—would drop their private insurance to enroll in the government plan.24

As Schakowsky so famously claimed in her April 2009 remarks, this government-run health plan would very quickly lead to single payer. Even if some employers wanted to try and keep their existing health plans, the rapid erosion of private insurance would quickly lead all but the most stubborn or foolhardy from maintaining their coverage offerings. Moreover, Democrats would likely use other political means to weaken, and ultimately eliminate, private health insurance.

To see how the Left would work to neuter private health insurance when compared to government programs, look at how private Medicare Advantage plans “compete” with traditional Medicare. When seniors sign up for Medicare, they’re not automatically enrolled in the lowest-cost plan. Seniors aren’t enrolled in the plan with the closest doctors, or the best care for their specific health conditions. No, seniors are automatically enrolled in the government-run plan.

Making the government-run plan the default for seniors gives traditional Medicare a major advantage against Medicare Advantage plans. Medicare Advantage plans must engage in intensive marketing efforts, and offer better benefits, to lure patients away from traditional Medicare. Yet the same experts who claim to want “financial neutrality” between the government-run plan and Medicare Advantage never acknowledge, let alone attempt to quantify, the financial advantage traditional Medicare receives as the default enrollment option.25

Even as Democrats claimed during the Obamacare debate that they would create a government-run “public option” on a “level playing field” with private insurance, Obamacare did the exact opposite with Medicare Advantage. As part of his budget proposal to Congress, President Obama outlined what he called a “competitive bidding” program for Medicare Advantage.26

But did Obama and Democrats allow Medicare Advantage to compete against government-run Medicare, by making Medicare Advantage the default option if plans could provide benefits more cheaply than traditional Medicare? Absolutely not. They wouldn’t dream of such a thing.

The bills described above include numerous provisions designed to “rig” the system in favor of the government-run option. To list but a few examples:

All these provisions would give a government-run health plan major advantages over private insurance. Moreover, the mere establishment of a government-run health plan with these inherent advantages would send a clear signal to financial markets, scaring away potential investors in ways that could lower insurers’ stock prices and choke off their access to capital.

Liberals have spent most of the time since President Trump’s inauguration complaining about how he and his administration are “sabotaging” Obamacare by deliberately allowing the law to fail.33 Ironically enough, however, that term aptly describes what liberals want to do to private health coverage, as the provisions above demonstrate. If ever a government-run plan competed against private insurance, the Left would find every conceivable way possible to sabotage the latter against the former, all to achieve their socialist dream of single-payer health care.

Democrats’ actions regarding private and government coverage render their words about a “level playing field” meaningless. For instance, Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY)—a presidential candidate and a co-sponsor of Sanders’s single-payer bill—said she “dared” private insurers to compete against a government-run health plan.34 In an MSNBC town hall, she said she also supported a government-run “public option as a transition…. I imagine within a few years, most Americans are going to choose Medicare because it’s quality and more affordable.”35 [Emphasis added.]

As with Schakowsky and Hacker, Gillibrand’s comments very clearly indicate that she wants to create a single-payer system, but would consider using a more politically palatable mechanism to arrive at that goal. Her comments also illustrate how her prediction that “most Americans are going to choose Medicare” will become a self-fulfilling prophecy, as she and her fellow Democrats will tilt the playing field so heavily in favor of a government-run health plan that it can become the “transition” to single payer they envision.

The evidence from their own words and proposals suggest that the Left wants to impose a single-payer health-care system on the United States—whether slowly or in one fell swoop, and whether the American people want it or not. To stave off the damaging consequences of such a change, conservatives need to articulate a better approach to fixing our health care markets.

1 Rep. Jan Schakowsky, remarks at Health Care for America Rally, April 18, 2009, video available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W_MtLyDfXJA.

2 Ibid.

3 Jia Lynn Yang, “The Man Who Invented Health Care’s ‘Public Option,’” Fortune, September 4, 2009, http://archive.fortune.com/2009/09/04/news/economy/public_option_hacker.fortune/index.htm.

4 Video available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3sTfZJBYo1I.

5 The summaries provided here include a discussion of the respective bills’ major provisions, as they relate to the expansion of Medicare and Medicaid and the functioning of insurance Exchanges. These brief summaries are not intended to be comprehensive, as many of the bills contain other provisions.

6 Unless otherwise noted, all bill numbers refer to legislative proposals introduced in the 116th Congress, which began in January 2019 and continues through 2020.

7 For more information on Obamacare’s original reinsurance and risk corridor programs, see Chris Jacobs, “Obamacare’s $170.8 Billion in Insurer Bailouts,” National Review, June 7, 2016, https://www.nationalreview.com/2016/06/obamacare-bailouts-billions-billions-billions-cant-keep-insurers-afloat/.

8 Linda Blumberg, John Holahan, and Stephen Zuckerman, “The Healthy America Plan: Building on the Best of Medicare and the Affordable Care Act,” Urban Institute, May 11, 2018, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/98432/2001826_2018.05.11_healthy_america_

final_1.pdf.

9 Ibid., p. 7.

10 Section 1401(a) of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, P.L. 111-148, codified at 26 U.S.C. 36B(c)(2)(B).

11 Chris Jacobs, “Democrats Consider How to Reinstate the Individual Mandate under a Different Name,” Federalist, May 17, 2018, https://thefederalist.com/2018/05/17/democrats-consider-reinstate-individual-mandate-different-name/.

12 Center for American Progress, “Medicare Extra for All: A Plan to Guarantee Universal Health Coverage in the United States,” February 2018, https://cdn.americanprogress.org/content/uploads/2018/02/21130514/MedicareExtra-report.pdf; Chris Jacobs, “Liberals Have a New Plan to Take Over the Health Care System—What You Need to Know,” Federalist February 23, 2018, https://thefederalist.com/2018/02/23/center-for-american-progress-drops-new-government-run-health-plan/.

13 Section 105(b)(3) of H.R. 2452, the Medicare for America Act of 2019.

14 Proposed Section 2205(f) of the Social Security Act, as included in Section 111 of H.R. 2452.

15 Proposed Section 2202(b)(4) of the Social Security Act, as included in Section 111 of H.R. 2452.

16 Chris Jacobs, “This New Democratic Plan Would Ban Private Medicine,” Wall Street Journal, May 13, 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/dems-new-plan-would-ban-private-medicine-11557688457.

17 For instance, when Mr. X dies, a stock he initially paid $5 to buy is worth $20. Ms. Y inherits the stock from Mr. X, and sells it at $30 per share. Under current tax law, Ms. Y would pay taxes on a realized gain of $10 per share—$30 minus $20—the “stepped-up basis” under which she inherited the stock. Under the proposal, Ms. Y would pay taxes on a realized gain of $25 per share—$30 minus Mr. X’s original purchase price of $5.

18 John Shatto and Kent Clemens, “Projected Medicare Expenditures under an Illustrative Scenario with Alternative Payment Updates to Medicare Providers,” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Office of the Actuary memorandum, April 22, 2019, https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/ReportsTrustFunds/Downloads/2019TRAlternativeScenario.pdf.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, A Data Book: Health Care Spending and the Medicare Program, June 15, 2018, http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/data-book/jun18_databookentirereport_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0, pp. 84-85.

22 Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy, March 15, 2019, http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar19_medpac_entirereport_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0, p. 89.

23 John Sheils and Randy Haught, “The Cost and Coverage Impacts of a Public Plan: Alternative Design Options,” Lewin Group Staff Working Paper #4, April 8, 2009, https://web.archive.org/web/20100611011954/http://www.lewin.com/content/publications/LewinCostandCoverageImpactsofPublicPlan-Alternative%20DesignOptions.pdf, p. 4.

24 Ibid., Figure 3, Public Plan Enrollment and Reduction in Private Coverage Under a Public Plan Using Medicare Payment Levels, p. 5.

25 See for instance Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy, March 15, 2009, http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/march-2009-report-to-congress-medicare-payment-policy.pdf?sfvrsn=0, Chapter 3, “The Medicare Advantage Program,” pp. 251-69. Such claims of “financial neutrality” also ignore evidence that Medicare Advantage plans create “spillover” savings to traditional Medicare; see for instance Katherine Baicker, Michael Chernew, and Jacob Robbins, “The Spillover Effects of Medicare Managed Care: Medicare Advantage and Hospital Utilization,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 19070, May 2013, http://www.nber.org/papers/w19070.pdf.

26 United States Office of Management and Budget, A New Era of Responsibility: Renewing America’s Promise, Fiscal Year 2010 budget submission to Congress, February 26, 2009, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BUDGET-2010-BUD/pdf/BUDGET-2010-BUD.pdf, p. 28.

27 Proposed Section 2208 of the Social Security Act, as included in Section 2 of S. 981, the Medicare-X Choice Act of 2019.

28 Proposed Section 2206(c) of the Social Security Act, as included in Section 111 of H.R. 2452.

29 Proposed Section 2201(b)(1) of the Social Security Act, as included in Section 2 of S. 981.

30 Proposed Section 2201(h) of the Social Security Act, as included in Section 2 of S.1261, the Choose Medicare Act.

31 Proposed Section 2202(b)(2)(A) of the Social Security Act, as included in Section 111 of H.R. 2452.

32 Center for American Progress, “Medicare Extra for All,” p. 4.

33 Chris Jacobs, “Let’s Examine New Charges That Trump IS ‘Sabotaging’ Obamacare,” Federalist, August 24, 2018, https://thefederalist.com/2018/08/24/lets-examine-new-charges-that-trump-is-sabotaging-obamacare/.

34 Elena Schneider, “Gillibrand Defends Handling of Harassment Complaints,” Politico, March 18, 2019, https://www.politico.com/story/2019/03/18/kirstengillibrand-sexual-harassment-1226466.

35 Ibid.