Chapter 1

A Rogue Wave

The sky sat oppressively close: an ominous presence. In the centre of the rapidly building storm it was impossible to perceive a dividing line, a visible horizon, between the heavens and the sea. Mist and rain obscured almost everything above the disturbed water. Overhead, virtually within reach but barely discernible, dirty grey clouds rushed southeast, trailing liquid curtains in their wake. A belligerent wind chased the clouds, leaving behind pernicious eddies to taunt the waves, bullying them to stand and fight or be destroyed and scattered as cowardly tears cast upon an ocean in turmoil. It was a day when sensible mariners preferred to be on shore, at home.

Gingerly I stood up, straddling my seat with one foot in the open cockpit and the other on a fuel tank. All around me, in and out of the mist, the frigid grey Bering Sea heaved and rolled with the storm. The rain blasted at me, stinging my face and pocking the sea with millions of miniature bullet holes. The darkening sky pushed down heavily, a malignant force reaching for the tops of the waves. The wind shrieked and moaned its displeasure at my presence. Audacity jerked viciously from right to left and back again, making it difficult for me to stay upright. Though it was not far away, the land lay hidden—blanketed by mist.

Standing, risky though it was in such seas, was the only way I could reach back far enough to switch from an empty fuel tank to a full one. My lifeline stretched from the dashboard to my waist, restricting my movements but keeping me on board. I unhooked one corner of the blue plastic tarpaulin to reach the tanks. Excited by the wind, the loose end flapped at my leg.

Balancing precariously, I quickly released the fuel-hose connection and snapped it on the second tank. Leaning from side to side, trying to copy the eccentric rhythm of the boat, I hastily clipped the tarpaulin back in place with a couple of short bungee cords. With my left hand extended to steady myself on the outboard motor cowling, still standing astride the back of my seat, I reached over with my right hand to restart the motor.

Rows of tiny hairs on the back of my half-exposed neck prickled in alarm. Warning bells pealed in my mind. Holding the starting cord’s handle, ready for a sharp pull, I shot a frightened look up and over my shoulder. Coming straight at me from the northwest was a vast wall of water, carelessly brushing competing waves aside. The serrated crest, bubbling white and scoring the sky, looked to be at least twice my height, perhaps far more. Momentarily paralyzed with shock, I watched in horror as the wave towered over me. A massive liquid Damoclean sword, it hovered and then began to descend with escalating ferocity.

Goaded into action by fear, I tore my eyes away and snapped my mind back to the job at hand. I wrenched hard on the cord, expecting the outboard motor to chatter into life immediately. Nothing happened.

“Prime it! Prime it!” I shouted at myself.

Bending from the waist, with my upper body almost horizontal, I reached for the bulb halfway along the fuel line. Frantically I squeezed it three times and let go. Before I could pull on the cord again, or get myself out of harm’s way, the breaking wave thundered down like a Rocky Mountain avalanche.

Boiling foam, icy cold, flooded Audacity, rose rapidly up my legs, enveloped my chest and picked me up. Effortlessly it hurled me from the boat, intent on drowning me. The wave’s momentum rolled me over, forcing my body deep below the surface. My weight, assisted by the wave’s unparalleled power, took me down in a headlong rush until flotation elements in my suit and life jacket asserted some of their own authority. Fighting solidly against the water’s pressure, they gradually arrested my descent into obli- vion. They had a job to do; they did it well. Somehow, in spite of myself, I kept my mouth and nose shut. The scream bubbling up inside, fighting to burst forth, dissipated as I focused my energy on finding air.

My hands and arms worked in unison to pull me up to the vague light above before eternal darkness overtook me. I rode a vertical airless tunnel no wider than my shoulders. Stroking powerfully, hampered by my clothing, I wondered if I would make the end of the tunnel in time. Each upward movement became a mammoth effort; still the light remained dim. My feet kicked hard. My fingers clawed for the sky. As my lungs screamed in protest, I broke free.

Surprised to be alive, I surfaced in the deepest part of a trough the errant wave had left behind and sucked in air and sea at the same time. Coughing and spluttering, I spat out the bitter-tasting salty fluid. With my body submerged in water only a few degrees above freezing and my face bare to the wind, the vicious blades of Arctic ice ripped into me, reminding me of their pitiless ability to rob me of life. I blinked salt from my eyes and scanned my immediate horizon. There was no sign of Audacity. I was alone.

Treading water, my full boots threatening to drag me under, I spun in a circle, my arms outstretched for balance, praying the boat was behind me, praying she was close enough to reach. There was only the threatening sea and lowering skies.

———

This was the stark reality of my passion. A passion that began as a dream; one that I had nurtured for years. My dream was to attempt a solo navigation of the fabled Northwest Passage. This commercially useless waterway, which traverses what is, for most of each year, an ice-choked realm, is strewn with enough hazards and obstacles to hinder, if not completely block, any boat’s progress.

The sea bed of the Northwest Passage is littered with the crushed hulls of expedition ships. Under the sea, countless bleached bones of doomed whalers, sailors and explorers move restlessly with the currents. On land they vibrate to the screaming of Arctic winds. To deliberately sail into the northern ice in search of possible riches, especially when one had little or no experience of the regions, was a fool’s game. From the 16th century until the 20th, many went, in spite of the risks. The potential for wealth and fame gave the quest an attraction out of all proportion to its dangers.

If there was indeed a route, and if the passage should prove navigable, as much as six thousand sea miles (11,100 kilometres) could be shaved off the journey from London to the Orient. The saving in time alone was attractive to the fiercely competitive merchants of the 16th and 17th centuries. As a result, many veterans of impressive ocean voyages joined the search for the passage, heedless of the incredible cold and unknown dangers that lay across their paths.

As background material for my own expedition, I studied the voyages of those who left their indelible marks on the history of the passage. Italian mariner John Cabot attempted to find the passage for the British. He crossed the Atlantic to Newfoundland in the caravel Matthew, but got no farther. On his second voyage, with a fleet of six ships, he vanished without a trace. Only one of his ships managed to limp to the safe haven of an Irish port. His son, Sebastian, while serving Spanish masters, believed he knew where the passage was. He was prepared to commit what amounted to treason to lead an English expedition north. He never got started, but he did perpetuate the myth of a westbound strait.

Martin Frobisher commanded the first British expedition to seek the passage after the failure of Cabot’s dream. Frobisher sailed with two small barques and an even smaller pinnace in 1576, with a combined crew of 39 men. Their voyage was fraught with danger. A disastrous gale in the North Atlantic, which lasted more than a week, caused the loss of the pinnace and four hands. Off Greenland they encountered polar ice for the first time. One ship, Michael, turned back for England, where her master erroneously reported the loss of Frobisher and his second ship, Gabriel.

Undaunted by the ice and fog, Frobisher pushed on to reach the western land. He sailed far up a fog-shrouded inlet, where ice floes continually threatened his ship, convinced he was on course for Cathay. In reality he was sailing on a vast bay—one that now bears his name. On land, Frobisher collected rocks, which he believed bore gold, and carried them back to England for analysis. A mini-gold rush ensued. The intrepid sailor was dispatched back to the Arctic to collect more of the supposed precious metal for his backers. Frobisher suffered through that and a third expedition, only to learn that his 1,200 tons of gold-bearing ore was nothing more valuable than iron pyrite, or “fool’s gold.” Despite the fact that his strenuous efforts achieved little of lasting value, Frobisher did add to the European knowledge of the “Eskimeaux.” And although its significance was not recognized until much later, he sailed deep into what is now known as Hudson Strait.

Frobisher’s failure to find the Northwest Passage was no deterrent to others. Over the next few centuries attempts were made by John Davis, Henry Hudson, Thomas Button, Robert Bylot, William Baffin, Luke Foxe, the brothers Ross and William Parry, and a host of others. All failed to find the elusive route. Some expeditions travelled overland across North America, while others kept to the sea, hoping to meet each other somewhere along the way.

Sir John Franklin, certainly the most famous of all those who braved the Arctic wastes, made attempts by land and by sea on separate expeditions. In many ways history depicts him as a bumbling incompetent, which he may have been at times, but his bravery and dedication to discovering a navigable route through the Arctic were beyond question. Without his noble efforts, the quest to find the Northwest Passage would have taken considerably longer. Franklin and the crews of his two ships, Erebus and Terror, disappeared without a trace on a Northwest Passage expedition that began in 1845. The ships, modern scientists have learned, were crushed by ice. Stranded far from civilization, the men perished on land, apparently unable, or unprepared, to live off the Arctic’s abundant supply of natural foods.

Once the Suez Canal was completed in 1869, there was no reason for shipping bound for China and Japan to venture west around South America’s Cape Horn, or east to round the Cape of Good Hope. There was no economic reason to continue searching for a passage through the northern ice. That fact didn’t stop adventurers from trying.

Between 1903 and 1906, over three hundred years after Frobisher’s first attempt, Roald Amundsen, a Norwegian, finally succeeded where so many others had failed. With a crew of six, Amundsen forced his 63-foot (19.21-metre) herring boat, Gjøa, from east to west from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. Amundsen, having beaten the British through the Northwest Passage, which they had long considered their exclusive territory, added insult to perceived injury. En route to his next adventure, he sent Royal Navy officer Robert Falcon Scott a terse message: “Going south–Amundsen.” In December 1911, Amundsen, the consummate polar explorer and sailor, stood with his companions at the South Pole. There they planted the Norwegian flag. A bitterly disappointed Scott and his doomed British party arrived one month after Amundsen. The Norwegians went home in triumph. The far-less-experienced Scott and his team, beaten by extreme cold and hunger, left their bodies in the Antarctic wasteland.

Three years later, in 1914, the Panama Canal was completed. With its stepping stones of gigantic locks, it proved to be the perfect short link between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. No sensible reasons remained for sacrificing lives in attempts to navigate the Northwest Passage. And still men tried.

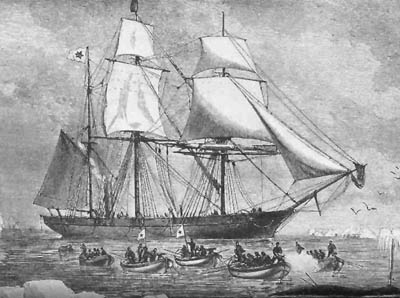

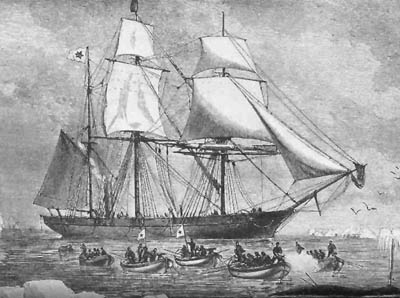

An Arctic whaler from the mid-19th century, with boats lowered and ready for the hunt.

Freshwater and Marine Image Bank, University of Washington

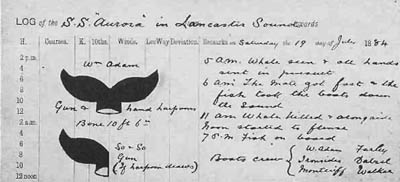

A typical page from a whaler’s logbook.

Freshwater and Marine Image Bank, University of Washington

Fleets of whaling ships had sailed into both eastern and western Arctic waters each summer since the mid 1800s. Their masters, however, had no interest in risking lives by searching for a route through the Northwest Passage—not that they considered the lives of their crews to be particularly important. Their objective was commerce, pure and simple: to seek and destroy whales, to fill their ships’ holds with barrels of valuable oil and with whalebone, and to get out safely.

My interest in the Arctic waters was far from commercial. For me it was all about adventure. Like the whalers, though, I planned to get out safely.

The Northwest Passage, according to the Pilot of Arctic Canada—the navigational bible for northern waters—stretches from Davis Strait and Baffin Bay in the east to Bering Strait in the west, effectively spanning the North American Arctic. Although I was well aware of the dangers to be faced, particularly if I were alone, I planned to take a close look at the passage from sea level. Perhaps I should have taken note of a comment by Arctic veteran George Fred Tilton: “Any Arctic whaleman will tell you that when a man goes into the Arctic he is a total stranger to conditions every year. In thirty-two years that I spent in the Arctic, I have never seen two summers alike as regards to ice.”

Tilton knew the truth of this. In the late summer of 1897, he was third mate on the steam auxiliary barque Belvedere, one of eight whaling ships that became trapped near Point Barrow when the polar pack closed in early. As a consequence, the lives of a few hundred men were in jeopardy.

Point Barrow was on my route. If the wind held the polar ice fast to the coast on both sides of the low-lying promontory, with no visible leads or open channels, I too would be stopped in my tracks. The unpredictable nature of the ice movements was part of the appeal for me.

For those who share a love of wild places and extreme goals, the risk is a large part of the eventual reward. Sometimes just striving to attain a barely accessible objective is as rich an experience as capturing the prize itself. I’m sure adrenaline had much to do with my adventures in the early days—that rush of nerves when attempting something bold; the flush of pleasure and surge of relief when successful—although I never tried to analyze my reasons. Adrenaline, at any age, is a natural stimulant, the effects of which are virtually impossible to beat. For as far back as I can remember, some inner engine has forced me on, pushed me to the limits, to test myself against the unknown.

This time, though, in the Subarctic waters of the wild and unpredictable Bering Sea, my quest for that all-important rush of adrenaline had landed me in dire straits. Alone, with only murderous waves and a volatile wind for company, my dream of travelling the Northwest Passage faded. A nightmare I had no wish to experience had begun.

President William McKinley.

Freshwater and Marine Image Bank, University of Washington