The wreck of a wooden coastal trading vessel rests with its back broken in Nome’s harbour.

Glen Colclough

Chapter 2

All the way to Anchorage I stared silently out the window at the clouds and the sea so far below. I was seated on the left side of the aircraft, and my wife, Penny, reclined beside me. Our friend Glen Colclough sat a few rows behind. Penny slept. Glen read a book. I thought about the journey ahead. Over and over, I went through the long equipment list in my mind, hoping nothing had been forgotten. I sat still, but fidgeted mentally.

At Anchorage we changed planes. As the Boeing 737 slid past Mount McKinley, en route for Nome, I studied the majestic snow-covered peak. Known to native Alaskans as Denali—the Great One—Mount McKinley was in perfect form to the north. The snowy flanks of the highest mountain in North America were ridged and creased, white alternating with dark shadows against a deep blue Alaskan sky. I fervently hoped the Arctic Ocean would look as inviting in a few days’ time.

It was raining when we arrived in Nome. We rented a pickup truck, loaded all the gear, including the stored freight I had shipped there a week earlier, and went in search of the Nome Nugget Inn. Our booking was for two rooms for two nights. That gave us the balance of our arrival day and all the following day to assemble Audacity and prepare for departure.

The rain stopped in late afternoon, though the sky remained mostly overcast. Eventually the cloud cover lifted a little and a few patches of blue bravely appeared to brighten the outlook. Occasional light showers drifted across the coast. The weather report suggested stable conditions over Norton Sound and the Bering Strait for the next two to three days. Having no first-hand experience of Alaska’s dynamic and unpredictable weather patterns, we willingly believed it.

Nome’s streets, including Front Street—the main road through town—were not kind to normal footwear. The day we arrived they were wet gravel. Following heavier rain, we soon learned, they degenerated into wide muddy trails.

After checking in to the Nugget and storing everything in the two rooms, we walked to the protected harbour where I planned to put Audacity back together and load her. A few wooden hulks rested on the mud flats. One, which appeared to have once been a reasonably elegant wooden coastal trading vessel, lay with her back broken, her neglected timbers grey with age and the scouring effects of wind and weather. Small motorboats and a few fishing vessels coloured the shoreline. A modern tug was tied to the wharf near a crane.

“This will do just fine,” I told Glen. “We can assemble her here on the hard ground tomorrow, and she’ll be safe overnight among the other boats.”

The wreck of a wooden coastal trading vessel rests with its back broken in Nome’s harbour.

Glen Colclough

———

We spent the next morning and early afternoon beside the harbour with Audacity, getting her ready for the sea. The sun shone; the wind was gentle. Outside the harbour, which is protected by a mole, or causeway, the sea was unusually calm. I felt happy in myself and positive about the expedition. If only the weather would stay fine for a couple of weeks, I would have an excellent chance of success.

While Glen and I worked on the boat, Penny supplied us with hot coffee and sandwiches. Sitting in the truck with the door open, wearing jeans, sweatshirt and knee-high leather boots, she looked contented and ready to go exploring herself.

Audacity, a four-metre-long inflatable speedboat built by the Metzeler company of Germany, was based on the successful Tornado model. She was fast and safe, powered by an outboard motor and with a double skin covering her hull for additional strength. I had put her together twice in Vancouver, so a third time in Nome was no great challenge. Each part was numbered and named in thick black ink from a marking pen.

Once Audacity was fully inflated, her air chambers tight as a drum skin, Glen fitted the dashboard, steering wheel and bench seat. I, meanwhile, tended to the Johnson outboard motor and fuel lines. Finally we mounted the engine on the rigid wooden transom and connected the steering and throttle cables. By three o’clock in the afternoon we were finished. The loading could wait until the hour before my departure, early the following morning. We spent the rest of the afternoon exploring the gold diggings on the hillsides beyond the town.

Nome was inadvertently founded in 1898 by a trio that later became known as “the three lucky Swedes.” Lindblom, Lindeberg (who was actually Norwegian) and Brynteson discovered gold in four creeks—Anvil, Glacier, Dry and Rock, all tributaries of the Snake River that feeds Nome’s harbour. The richest claim was on Anvil Creek, although the team staked as many as 30 claims bordering that and the other three icy streams. Word of the strike travelled fast. By May 1899, Anvil City, population 250, was established at the mouth of the Snake River. Just over a year later, as the summer of 1900 came to a close, there were 20,000 people in the ever-growing community. Prospectors and adventurers sailed in from the far corners of the world, all intent on making their fortune. Many did just that. They found that the beaches were liberally sprinkled with gold. Men and women worked side by side through the daylight hours to rake the waterfront.

By 1901 the golden sands along the shore had yielded $2 million worth of the prized yellow metal. Anvil City, by then incorporated as the City of Nome, had grown from a small camp to a sprawling metropolis. There were tents, wooden shacks, houses, a few elegant homes, at least 25 saloons, a handful of hotels, and one or more representatives of just about any business venture to be found in a city today, including a thriving red-light district. The purveyors of the world’s oldest profession were not about to miss their own gold rush.

As the amount of gold recovered from the beaches declined, the prospectors moved inland. They panned the creeks and streams, the foothills and the backdrop of rounded peaks. They probed at the tundra itself in their determined search. There were few places on land, within sight of Nome, where a miner had not dug or sifted. In a little over a decade, $60 million worth of gold was discovered, and much of it passed into the economy of the incomparable wilderness that was Alaska.

Nome, Alaska, circa 1900, during the gold rush.

Freshwater and Marine Image Bank, University of Washington

More than a century earlier, in the summer of 1778, Captain James Cook had passed by this area as he searched for a western entry to the Northwest Passage. He managed to reach the latitude of Icy Cape, which he named, before being blocked by pack ice. After retreating from the Arctic ice and touching on Siberia, he approached the Alaskan mainland again off present-day Nome. One of his final notations in the region was to name Norton Sound, a salute to the Speaker of the British House of Commons, Sir Fletcher Norton.

Cape Nome—the high promontory rising 200 metres above sea level southeast of the city—has its own intriguing history. Legend tells that, in 1850, an officer on board HMS Herald, part of a British expeditionary force searching for clues to the disappearance of the Franklin expedition, wrote “? Name” on his navigational chart to mark the spot where the unnamed cape stood. It has been suggested that the “?” was interpreted as a “C” and the “a” was read as an “o.” True or not, Nome is named for Cape Nome and the officer’s annotation has taken a permanent place on maps and marine charts of the western Alaskan coast.

Lieutenant D. Jarvis, leader of the US Revenue Cutter Service’s Overland Relief Expedition, came through here with ship’s surgeon Dr. S.J. Call on his way to Cape Prince of Wales to collect a reindeer herd in January 1898. They made camp in the lee of Cape Nome to shelter from a blizzard. The beaches, not yet known for their gold, were carpeted in a thick layer of snow. Jarvis and Call unsuspectingly walked over incredible riches on the frozen beaches and missed the gold rush by only a few months.

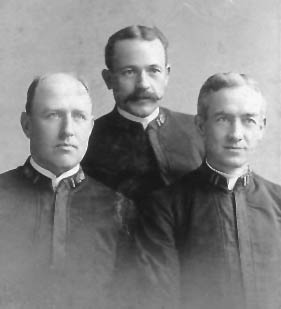

The assigned members of the Overland Relief Expedition: Lt. Ellsworth Bertholf, Dr. S.J. Call and Lt. David Jarvis.

Freshwater and Marine Image Bank, University of Washington

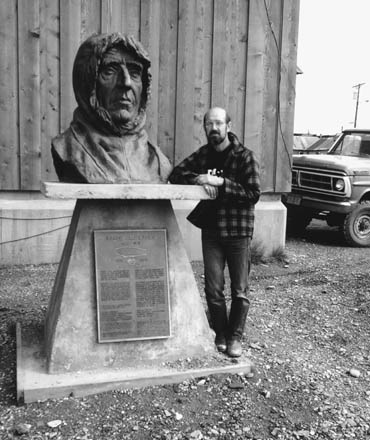

Amundsen’s Gjøa called in at Nome in 1906 at the end of the Norwegian explorer’s three-year voyage through the Northwest Passage from east to west. The town went wild, or so the stories say. Certainly Amundsen’s epic voyage has been recognized by Nome’s citizens. There’s a bust of the great polar explorer, larger than life-size, mounted on a pedestal in Nome and looking out to sea.

———

Standing on the hillside, with the silent rusting remains of Bessie (a huge dredge) behind me, I stared out over the vast expanse of Norton Sound. A familiar restlessness tugged at me. The sea was rolling, that much I knew, even though we were some distance inland and quite high up. It looked smooth—no whitecaps; no obvious breaking waves, except along the beaches. It was time to get moving. A charted course was waiting. The peaceful maritime scene couldn’t last forever. Already I had wasted a couple of hours of near-perfect weather. In the morning I planned to be on my way.

The author meets Roald Amundsen, who captained Gjøa, the first vessel to transit the Northwest Passage between 1903 and 1906.

Glen Colclough

That night, while we slept in comfort when I could have been many hours away to the north and west, the clouds rolled in from the sea. The wind came up. By breakfast time the waves were crashing in endless progression onto the shore. Heavy rain pelted Nome for hours. The meteorological office posted a small craft advisory.

Glen and I went to check the size of the swells rolling into the harbour through the artificial channel, or chute. Beside the long mole, a crowd of Inupiat boys played fully dressed in the surf, getting soaked and soaking each other. Oblivious to the cold, they were thoroughly enjoying a day at the beach.

The surf brought in the sea’s rejected waste. Bits of broken wood mingled with broken glass—the edges of which were blunted by constant churning—and odd pieces of Styrofoam, coffee cups, irregular shapes. There were no riches to be seen. Where the waves broke over the shore, we could clearly see the heavy burden of sand particles, but no gold. Dredged up by the undertow and sluiced out to sea, the sand was carried back to alter the coastline a little more with each deposit. Every wave carried an infinitesimal amount of evolution, in addition to the flotsam and jetsam.

While Glen talked to the kids, I walked out on the slippery rocks to the end of the mole where the chute opened to the sea. Whitecaps stretched to the southern horizon, each one aimed at Nome, each one on course to disintegrate on contact with Alaska. Glen joined me.

“You’re not thinking of going out in that, are you?” he asked, concern etched on his usually lively face.

“No, I’m not. I should have left yesterday afternoon when I had the chance.”

“You’d still be stuck somewhere on a beach today. This weather goes a long way north.”

“Maybe,” I replied, “but I would be on my way.”

The first sensation of nervousness began to worry at me. Glen said something else. I shook my head, only half listening, mentally upbraiding myself for not having left as soon as Audacity was assembled. The state of the sea disturbed me more than I cared to admit. After the deceptive calm of the previous day, I was bitterly disappointed by the unruly scene before me. I wanted to get going, but the waves, and the wind that ripped the tops off them, scared me. Fleetingly I thought of abandoning the expedition before it began. Biting my lip, I stood for a long time in silence. I watched each wave as it approached, studied its pattern, memorized the way it reacted to the wind and the speed with which it swept to destruction on the concrete mole.

As I watched, though the anxiety was strong, I felt my confidence returning. Standing on solid ground, legs braced apart in defiance of the wind, I began to sway with the motion of the sea. Closing my eyes, I could imagine the buoyancy of Audacity under me as she lifted herself without hesitation and took on the waves.

Deep-throated engine noises brought me back. Hooper Bay, a seagoing tug towing two huge barges forced its way out of the protected harbour. It passed almost close enough to touch. In his late teens, Glen had worked for a while as a deckhand on tugs in the North Pacific and on the southern rim of the Bering Sea. He grinned and nodded his head in appreciation as the tug reared up, its strengthened bow crashing through the first of the breakers. I wondered how I would fare under such conditions. The inactivity was getting to me. I had to do something constructive, something involving Audacity and the sea. I needed to feel the interaction of both.

“I think I’ll try Audacity in the chute,” I shouted above the wind, turning my back on the waves. Penny met us en route to the boat, and a few moments later I was on board and heading out of the harbour. To my delight, Audacity handled the clearly defined rollers extremely well. Glen and Penny, watching from the concrete wall, both later agreed she looked capable and seaworthy. I felt the same—until I took her close to the whitecaps near the mouth. She was in her element and well able to handle the conditions, no doubt about that. Her skipper, however, had less confidence in his own abilities that morning.

Audacity performed well at speed in the turbulent waters of the channel leading to Nome’s harbour.

Glen Colclough

I held Audacity virtually motionless at the end of the mole, letting the rollers lift her and pass under. Each breaker that entered the chute forced us back a pace. On top of an inbound roller, having seen what I wanted, I turned Audacity in her own length. With white water rapidly advancing, I opened the throttle wide and raced the almost empty boat at full speed back to the harbour. Audacity screamed up the rollers and leapt joyfully off, with only her propeller touching the murky brown water. Every few seconds we repeated the trick for my amusement and, perhaps, to impress those on shore. It was an exhilarating ride. As I tied Audacity to shore after the experiment, I looked around the harbour, wondering where Amundsen had moored Gjøa so long before.

For much of that afternoon my mind wandered between gold miners, Arctic explorers, the fast-diminishing summer and the storm attacking Nome. That night, after walking the beach alone, hands in my pockets, shoulders hunched, head bowed to the rain and wind, I wrote a few lines in my journal about my impressions of Nome: “It’s quiet now, the gold rush no more than a memory. The beaches are littered with mud, sand, pebbles and stones of all shapes and sizes. The massive waves crash relentlessly on the once golden shore. Rain; cold, constant, wet, mingles with the salty spray as I walk, watch and wait for the storm to subside so I can go to sea.”

Pilot Clara Johanssen, the author, Arnie Johanssen and Penny Dalton beside the Johanssens’ Cessna at Nome’s airport.

Glen Colclough

The wait for fairer weather was frustrating, but there were occasional bright moments. And as we learned one night in the Nugget’s bar, we weren’t the only ones trying to get out. Arnie and Clara Johanssen joined us for a drink and told us a fascinating story. This retired couple, both probably in their late 60s, had flown from their Wisconsin home to Alaska in their own Cessna 172. Clara, Arnie proudly told us, was the chief pilot for their adventure and was a member of the Ninety-Nines—an international organization of women flyers. Clara was petite, with a big welcoming smile. Her bright blue eyes were ringed by clear-framed spectacles. By contrast, Arnie towered over her, his shoulders level with the top of her head. Behind his dark horn-rimmed glasses, his eyes sparkled with pleasure as he told of his wife’s skills.

They planned to visit many of the same coastal settlements as I, though in considerably more comfort and warmth. We agreed to watch out for each other once the weather relented and allowed us to continue our respective journeys.

On a blustery Sunday we attended church with the Johanssens at Our Saviour’s Lutheran, on the corner of 5th and Bering Streets. The Reverend Duane Hanson officiated, aided by Reverend Steve Dahl from Shishmaref. Having heard about our plans, the minister thoughtfully offered prayers for the safety of the visiting adventurers. An invitation to partake of coffee, tea or juice in the church library after the service could not be ignored. I made a point of introducing myself to Steve Dahl, who immediately invited me to make a stop in Shishmaref to visit his congregation on my way north. We agreed to meet again in a few days, after Audacity’s passage through the Bering Strait.

Outside the church I suggested a visit to the cemetery. I’m fascinated by the rows of grave markers in stone, wood and sometimes metal. There’s nothing morbid in my interest. To me a graveyard is an important final chapter in the lives of those who have lived, loved and died in a community. There is much to be learned about the history of a place and its early residents from reading tombstones.

Perhaps guided by a premonition of disaster, Penny was vehemently opposed to any such excursion. “We are not going to a cemetery,” she insisted.

Her demeanour offered no possibility of argument or subtle bargaining. Penny had spoken. We didn’t go.

At 9:00 AM on Monday, July 30, the meteorological office at the airport issued another gale warning for Norton Sound. The reported storms threatened a large area, including Nome, Cape Wales and the Bering Strait north to Kotzebue Sound. A coastal flood watch went into effect for Nome. Southeast winds would be increasing to 35 knots during the morning, then shifting to the southwest and briefly diminishing to 20 knots later in the afternoon. By nightfall the wind would be westerly at 25 knots. Seas were expected to be 16 feet (4.87 metres), subsiding to half that later in the day and increasing again to about 10 feet (3 metres) during the night. Only a mariner with suicidal tendencies would go to sea in a small boat under such conditions. We waited. And we waited some more.

That evening Glen and I walked out to the airstrip to see how Arnie and Clara were faring. We were concerned that the storm might have damaged their plane, or that they might be in some kind of trouble. We needn’t have worried. The two intrepid aviators, old enough to be our parents, were tucked snugly in their sleeping bags in the plane, reading books by an overhead light. To counteract the wind, they had tied the plane’s wings and tail section to rings set in the tarmac for that purpose. The Johanssens were warm and comfortable but pleased to see us all the same. We promised to get a copy of the weather report and give it to them in the morning.

At 10:00 PM the marine forecast was no better. Another gale warning, high winds, rain and big seas. A carbon copy, almost, of that morning’s report. Twelve hours later there was still no improvement. Gale warnings were issued throughout the area. The cryptic reports announced “Wind and sea dangerous to all but the largest vessels.” We waited again. Normally of positive mien, I was beginning to feel decidedly dispirited.

Fate delivered a small consolation. During the day I heard there was a telegram for me at Alascom, the telephone company. Addressed to me and Audacity, in care of the mayor of Nome, it read simply, “Congrats. Best of luck and love.” It was signed Shirley Turner, Toronto, Canada. Somehow Shirley, an ex-girlfriend from the mid-1970s, had learned of my plans and tracked me down. I was thrilled to have the good wishes and cheered up immediately.

To save money we moved into one room with two single beds. Glen ran a clothesline down the middle of the room, at head height, and draped my sleeping bag over it to provide a modicum of privacy for Penny and me.

Ever the optimist, Glen made repeated trips to the meteorological office only to return disappointed each time. No changes for the better were imminent. The delay and dreary weather conditions began to prey on our nerves. Going solo did not seem such a good idea to me after all. I began to wish Glen could go with me. My defences were falling rapidly.

The three of us found ourselves searching for anything to brighten the long hours of each day. I sought solace in work, keeping my sponsors and the news media informed of our progress—or lack of it. A couple of radio interviews, conducted by telephone, gave Penny considerable amusement. She lounged against the door as I described the scene outside our window one miserable morning.

“The storm is pounding the shore, with spray reaching to spit at the rooftops. Endless processions of whitecaps patrol Norton Sound from horizon to horizon. Rain is beating heavily on the windows and rooftops of the community. The incessant wind keeps driving harsh weather before it.”

Our window did not face the sea. We overlooked a muddy street that was getting wetter by the minute. The essence of the storm was behind me, through a wall, across a corridor, and through two more walls. As I hung up I glanced at Penny’s wide smile, aware of what she was thinking.

“Well, that’s exactly what I would see if our room faced south,” I defended myself. “I was out there only a few minutes ago.”

Later, while reading some old articles about Nome and the Seward Peninsula, I came across an interesting and amusing item. The Alaskan sourdoughs, it said, referred to the equinoctial storms as “unequalled and obnoxious.” I understood that. I too was tired of the Bering Sea gales, none of which, so far, according to the locals, had been spectacularly severe.

It didn’t seem right, somehow, to have so much bad weather congregating in one place. On most days there was far more wind and rain than Nome needed. Rain and fog obscure visibility, which I most definitely needed. And the worst part, for me, was the high winds creating big waves. Without actually experiencing the phenomenon, it’s almost impossible to comprehend the enormous power of a wave driven by an Arctic storm. Those hardy folks who reside year-round on Alaska’s north and west coasts know only too well the havoc nature’s violence can cause. Soon I was to discover for myself the power of storms that could, as the locals say, “regularly cause the wrath of the Bering Sea to wreck Nome.”

From my journal: “July 31st, impatiently waiting for departure. The weather report is depressing, as it has been for five days. A gale warning is still posted for Norton Sound, with a coastal flood watch for the southern Seward Peninsula until noon. Winds southwest at 35 knots, diminishing to 20 knots by nightfall, variable to 15 knots for the following day. Gusts of up to 65 knots have been reported in the Bering Strait. Seas running at 12 feet (3.65 metres) diminishing to 5 feet (1.52 metres) by next morning. Showers all day and some fog by nightfall. The outlook offers a southeast wind up to 25 knots. Not a good forecast for me. Another day of frustration.”

Wandering in the wind and rain—sometimes with Penny and Glen, sometimes alone with only my depressed thoughts for company—I mulled over the situation. If the weather didn’t break soon, I would have to make a choice between taking an enormous risk or abandoning the expedition for that season. Neither idea appealed to me. My nerves were stretching closer and closer to breaking point.

A local, who came to chat with me while I paced the harbour in sheeting rain, confided, “The October storms have started early this year.”

It wasn’t what I wanted to hear. The day dragged. We checked Audacity to make sure the tarpaulin was keeping the rain out. We checked the weather report again. We stood in the pelting rain and watched the Bering Sea attacking Nome. We talked. Often I stayed awake for much of the night, listening to the wind and rain.

Early on the morning of August 1, the rain continued to fall, but the seas were down. Most of the whitecaps had gone, finally, though the heavy chop was still there. The swells rolled ceaselessly on shore and crashed into foam. In the chute they reached about a metre in height and perhaps two or three metres apart. I stood on the mole for a while, watching the action as I had done regularly for days, gauging the movements I would have to make when I left. Getting out of the chute would be the most dangerous part of the day as far as I could see. The chop beyond the breakwater, out where I would have to make a sharp 90-degree turn to the right, would also need to be handled carefully.

I looked west-northwest toward the Bering Strait. In the foreground was dirty grey sea. Beyond that was mist. Clear skies, sunshine, calm sea, no wind: that would have been perfect. The day offered to me was far from ideal. In truth it was decidedly unpleasant, but it was probably the best I would see for a while. Certainly the preceding days had been abysmal and the future didn’t look much brighter. Unable to decide what to do, I pulled my collar up around my ears to ward off the rain and studied the sea for a while longer. Could I safely work with it?

“Well,” I looked at Glen as he joined me, “the sea is down, but not by much. The wind has slackened too. I wonder for how long.”

“This is the best it’s been for days,” Glen encouraged. “You might not get another chance.”

“You’re right. I don’t like the look of that beam sea, but I reckon I can handle it.”

We stood for a moment in silence. I knew what I had to do. The adrenaline began to build inside me. It was time to leave.

“Okay, Glen,” I said, my mind made up. “Let’s go.”

It didn’t take long to collect Penny and load the pickup. We took a detour via the gas station to fill the main fuel tanks. The other two, smaller ones, were already full. The rain still fell lightly, an insistent drizzle that soaked anything exposed in seconds. I struggled into my Mustang flotation suit and pulled on a life jacket while Glen hooked the first tank to the motor.

We had practised loading the boat in Vancouver and again in Nome. We thought we had perfected the art. In the rain, and with departure imminent, the scene was chaotic as the three of us ran between truck and boat with supplies. Somehow, in spite of ourselves, we managed to stow all my gear properly before it could get too wet. Audacity soon sat trim and on an even keel, perfectly balanced for departure.

“This is it,” I said.

“You be careful,” Penny warned as she and Glen took photographs.

“Don’t worry. I promise I will not get myself killed up there in the Arctic.”

I gave them each a hug and stepped aboard. It was 10:20 in the morning. Suddenly I felt very much alone, small and insignificant. All pre-departure decisions had been made. Today, and for all the days to come, until I returned home in triumph—or in defeat—the decisions would be based on prevailing conditions. The decision of the moment was “Go.”

Instinctively my right thumb responded to Glen’s good luck signal. Time to go. I pulled hard on the starter cord and the Johnson outboard caught first time. Gritting my teeth, adrenaline coursing through me in response to the hidden stress and the excitement of the start, I slipped into reverse gear and backed away from the shore. Trying to calm myself, I waved once and turned away. Selecting forward, I pulled Audacity in a wide circle to pass the broken hulk on the sandbar and headed toward the chute. The roller-coaster ride had begun.

With the wind blowing rain in my face, and the first swells lifting Audacity’s hull, I reached for the open sea. Rollers ran a metre to a metre and a half in height throughout the chute. Nervously at first, I rode slowly up and down an endless succession of watery mounds. Audacity felt less skittish with a load on than she had earlier when empty. Slowly I increased power. Audacity responded and began to lift her bow confidently off the tops of the rollers. Penny and Glen waved from the seawall on my left. I raised a hand in farewell salute, then concentrated on my chosen task.

Whitecaps marked the ends of the breakwater’s two arms and the beginning of the waters of Norton Sound. I crested incoming seas, ducking behind the windshield as a couple of waves broke over the bow. I raised my body a little for better vision, and the next wave caught me full in the face. With cold seawater streaming off me, I turned Audacity to the west.

The sea was choppy pewter, but lower than predicted by the weather synopsis. After a few anxious moments I began to get a feel for the rhythm. Visibility was not much more than a couple of hundred metres. The cloud ceiling was perhaps less than two hundred. The wind was light; the rain getting noticeably heavier. Behind me the motor purred comfortingly. Briefly I looked back over my shoulder at Nome. During our stay there it had been cold, wet and dreary most of the time. As the weather-scarred buildings merged with the mist I could, for the first time, feel its warmth.

Back there in Nome, Penny and Glen were racing to the airport. A flight was due to leave soon for Anchorage, and they wanted to be on board. With no time to change out of their wet clothes, they returned the truck to the rental agency, boarded the aircraft still soaked and changed into dry clothes on the plane. The jet took off, probably heading inland, because I neither heard it nor saw it.

Under way, I found myself moving around on the seat, trying to get comfortable but never quite able to do so. I shifted from side to side, put my feet first one way, then another. I rested my right elbow on the gunwale. Took it off again. I stood up and stretched, catching the wind in my face.

“Come on,” I urged, “settle down.”

I glanced at the sky, hoping for a slit in the clouds that would send a beam of reassuring sunlight to guide my way. The grey glared back at me. After the long days of delay, my nerves were ragged, much too ragged. I needed to get them tidy again. Gloomy skies have always depressed me. The long wait in Nome had picked at my confidence until it drew metaphorical blood. Finally at sea, the encompassing grey, above, below, ahead and behind, unbalanced my usually bright outlook and badly upset my mental equilibrium.

For the first hour, until I became accustomed to the purring, I listened carefully to the sound of my motor. I heard its every beat. Any time we crested a wave too fast, causing the propeller to lift out of the water momentarily, the additional whine dug into my brain. As the minutes ticked by, my confidence grew. My subconscious took over and monitored the engine for me.

Hugging the barely visible coast of the Seward Peninsula, I expected to come abeam of Sledge Island within 90 minutes after leaving Nome, but I passed its granite bulk without seeing it through the rapidly thickening fog.

On August 4, 1778, Captain James Cook anchored HMS Resolution in the lea of the island. There was fog that day too. In spite of the conditions, Cook took a party ashore for a reconnaissance. He estimated the high rocky island’s circumference to be four leagues (approximately 20 kilometres). On shore, Cook found a wooden sledge with whalebone shoes, about three metres in length. He deduced the sturdily built conveyance, bound together with wood pins and hide thongs, had been fashioned by Natives. His find prompted the designation Sledge Island.

My current navigation chart, far superior to anything Resolution carried, sat on the seat beside me in a sealed plastic map case for quick and easy reference, particularly to identify visible landmarks. In thickening fog, few were recognizable. I passed the mouth of the Sinuk River without noticing it. The chart insisted it was there, but the fog made a mockery of the cartographer’s precision. Off Cape Rodney, which was also hidden in the mist, a disturbance in the water attracted my attention. It looked like breakers swirling round and over a smooth black rock. I spun the wheel seawards to give it a fairly wide berth. A glance at my chart showed no rocks were marked in the vicinity.

A slight pressure wave stood in front of the object. A vague wake trailed behind. The unmarked, uncharted “rock” was moving—moving toward me, travelling south, perhaps en route to the breeding grounds of the distant Sea of Cortez. A long sleek back, encrusted with barnacles, showed momentarily before twin flukes flashed and the whale sounded.

“Good luck,” I called. “Have a safe journey.”

Seeing the whale brightened my outlook. I felt it augured well, without questioning why I was going north, while the whale, with far superior local knowledge, was migrating south. Thinking of the whale’s course for more hospitable latitudes, I took off a glove and trailed my right hand in the water running past. It was icy cold. Instinctively I shuddered. Wiping my hand on my suit, I replaced the glove, my fingers grasping at the warmth.

The sea, which had shown a few whitecaps off Nome, and which was supposed to subside, was getting wilder. I had yet to learn this was a pattern that repeated itself over and over throughout the summer, though not always as violently as it was doing this year. The wind increased and the waves built up. A couple of seals popped their heads up to take a look at the humming intruder; otherwise I was alone.

I passed Cape Woolley and the long sweeping bay between it and Cape Douglas without seeing them. Far to the west, all alone in the Bering Sea, King Island—famous for its Inupiat dancers—was 45 nautical miles (83 kilometres) off my port side.

Wrapped in the Subarctic mist, I felt as though I was enveloped in an ethereal world where few other known life forms existed. There was Audacity, and there was me. Together we floated in the nucleus of a restricted world. There was spray. There was rain. There was fog. There was nothing else. The sensation was both strangely beautiful and a little frightening. I began to imagine sea monsters hiding beneath the surface, preparing to pounce on Audacity as she cruised overhead. The increasing turbulence of the sea drew my mind back from the brink of fantasy to more rational matters.

At home I had packed two dozen clear plastic bags with nuts and dried fruit—good old raisins and peanuts, or GORP, as mountain climbers like to call it. Good for energy and tasty as snacks, I had reasoned that the mixture would make an effective and satisfying substitute for on-board lunches. The first handful, tasted in concert with salty spray, was all I needed for a quick fill-up and a restoration of my mental faculties to the job at hand.

For a while I kept a steady course well clear of land, concerned about shoals and sandbars close in. I steered by compass and instinct alone. Although I was far from relaxed, I was no longer on edge. The expedition I had envisaged for so long was in progress. My will to succeed dominated my actions and strengthened my mind.

Sometime in the afternoon, sure that I must be in the vicinity of the narrow spit of land leading to Point Spencer, I closed with the shore again until it was just visible as a dark grey line through the fog.

According to information I had received in Nome, I should have been able to see the LORAN navigation tower at Port Clarence (the U.S. Coast Guard station on Point Spencer) from a good distance away. The red lights on top, warning beacons for incoming military aircraft over 400 metres above sea level, should have been visible from afar. Instead the fog shivered over the tundra, shrouding them, hiding their welcome beams.

I was almost level with the tower before its ghostly lower struts were visible through the mist and spray. Shadowy figures of two men stood on the shore; they pointed at me and raised their arms in greeting. I was too busy bucking increasingly large waves to respond. Coastal Alaska’s reputation for ignoring weather reports was proving well-founded.

Breaking seas that crashed on the sandbars protecting the tip of Point Spencer sent me well out to sea again. As a precaution I took a compass bearing on the almost-invisible tower for future reference. I planned to round the point about one kilometre out, not knowing what unseen obstructions might be lurking just under the surface to cause me grief.

Out there I was no longer able to discern land, and the sea was confused as hell. Conflicting waves collided clumsily with each other and with me. As I surfed over one wave, another hit me from a different angle. The wind, too, had no defined direction. It played with the waves, worrying them, building them, tearing them apart, making them cry spindrift tears. My hands ached from gripping the wheel, and my body began to complain loudly as we were pummelled and shaken from side to side.

As Audacity slid out of control down the back of one wave, the motor spluttered, coughed a couple of times, resumed purring, coughed again and cut out. I had been so busy keeping her upright that I had forgotten time and distance: the first fuel tank had run dry. Suddenly we were being tossed like a cork, without power, on an unfriendly sea. I stood up and reached behind me to unclip a corner of the tarpaulin covering the tanks. It began to flap viciously in the wind.

Partially off balance, trying to change tanks and restart the motor, I was a clear target for the baleful rogue wave that attacked with almost no warning. It catapulted me from the security of Audacity, casting me into the sea.