The Arctic has long been a magnet for adventurers, explorers, traders, hunters, misfits and, in relatively recent years, scientists. It is, however, an unpredictable region where weather conditions can change in minutes. As a consequence, even those fully equipped for the capricious attitude of the northern elements can find themselves in severe trouble. For the physically and mentally unprepared, the Arctic can be forbidding and unforgiving.

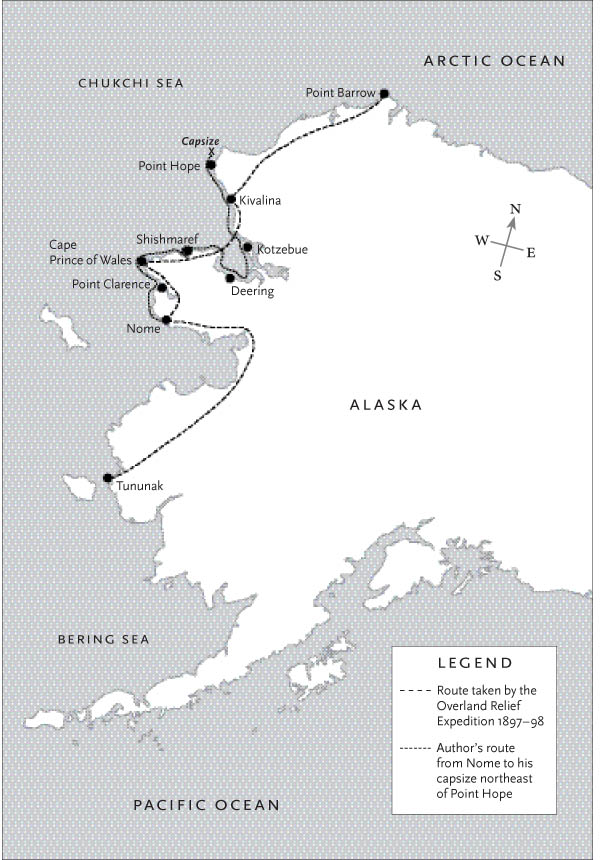

For hundreds of years the Arctic rebuffed the probing attentions of the Royal Navy, at that time the most skilled and strongest nautical force on our planet. Even when it finally allowed a small Norwegian herring boat, Gjøa, to venture from east to west through the Canadian Arctic islands, it did so reluctantly—keeping the vessel in its icy embrace for the best part of three years, from 1903 to 1906. Whalers from Europe and from the Americas came and went in search of living leviathans wherever there was a chance of open water. Although a high proportion lived to return home, too many of the ships did not survive. They were crushed by massive ice and scattered on the sea bed. Their crews left their bones in the north, as had so many explorers. Among those who survived the deadly pressure of the constantly moving ice was a small fleet of whalers trapped in the vicinity of Point Barrow, Alaska, in the late summer of 1897. The official Overland Relief Expedition, which travelled through a harsh Alaskan winter to supply food to the men, is one of the great tales of Arctic expeditionary lore.

So if the Arctic is so dangerous, why do men go there? Explorers, such as the officers of the Royal Navy expeditions, went in search of glory—for their nations and, assuredly, for themselves. The whalers risked all for the chance of riches. Traders, too, braved the dangers, venturing into the north to seek their fortunes. Then there are the adventurers and the misfits: those who went with no greater purpose than to see for themselves what the Arctic had to offer. I belong in the latter category, although whether I rank as an adventurer or as a misfit, only my family really knows.

I first went to the Arctic in the 1970s. Hiking in the Penny Highlands in what would one day become Auyuittuq National Park on Baffin Island, I became one more convert to that group of people who have fallen under the spell of the far north. A couple of years later I flew from east to west across the Canadian Arctic in a series of small planes, hopping from one settlement to the next. I went back in the 1980s on two separate adventures. In the middle of that decade I roamed the southern part of Victoria Island, by air and by land, from a base in Cambridge Bay with two companions. We were there primarily to fish for northern lake trout and Arctic char. We caught both in abundance, and my appreciation for the north grew.

A year or so earlier, in 1984, I had taken a close look at Alaska’s northwestern coastline from the helm of a small boat. Travelling alone, on an extremely personal journey, I started from Nome and worked my way through the Bering Strait and along the coast for hundreds of nautical miles. I had planned to go all the way to the Yukon and on through the rest of the Northwest Passage to Baffin Island. The Arctic, however, ruled otherwise.

I learned, as other adventurers and explorers have learned and as the crews of whaling ships knew so well, the Arctic guards its territories jealously, using formidable weather as both a deterrent and a weapon against intruders. This book is the story of my Alaskan coastal voyage, paralleled in sidebars with the wintry tale of the Overland Relief Expedition, which travelled along the same stretch of coastline a century earlier to herd hundreds of reindeer north to feed the crews of whalers trapped in ice near Point Barrow.

Much of the financing for my voyage came out of my own pockets. I was, however, fortunate that a few sponsors supplied equipment and/or services to help defray the costs. The names of those sponsors are listed in the acknowledgements. Having sponsorship made it imperative that I gain as much news media attention on the expedition as possible. I accomplished this by making regular telephone calls from the settlements I stopped at on my journey.

———